Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Ylva Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Girl Meets Girl series

- Sprache: Englisch

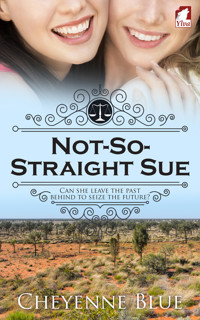

"Sorry, I'm straight." Until she's not. A coming-out romance full of awkward moments, big dreams, and small-town charm. "Sorry, I'm straight." Those words, accompanied by a smile, were the ones Sue Brent, an Australian lawyer living in London, always used to turn down women. But the truth was buried so deep that even her best friend, Nora, didn't know that Sue was queer. Sometimes Sue even managed to convince herself. The only person in London who'd ever seen through her façade was Moni, an American tourist. When a date with a friend's brother goes disastrously wrong, Sue has to confront the truth about herself. Leaving London, she returns to Australia to take up the reins in an outback law practice. Back in the country of her birth, she is finally able to accept who she is. When Moni arrives in outback Queensland to work as a doctor, Sue starts to see a path to happiness. But when Sue's teenage love, Denise, tracks Sue down in Mungabilly Creek to beg a favor, Sue and Moni's burgeoning relationship is put to the test.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 435

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Sign up for our newsletter to hear

about new and upcoming releases.

www.ylva-publishing.com

BOOKS IN THE SERIES GIRL MEETS GIRL

Never-Tied Nora

Not-So-Straight Sue

Fenced-In Felix(Coming November 2016)

DEDICATION

For D, with love and thanks for the support. Always.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Writing is solitary, but the final product that you hold in your hand owes much to many people’s efforts and contributions.

Huge thanks go to Glendon of Streetlight Graphics, who has once again produced a cover that I love and which completely captures the mood and theme of my story.

Massive thanks go to the team at Ylva Publishing for their professionalism, good humour, and above all the hard work and dedication they put in to ensure that any story they publish is as good as it possibly can be. In particular, my thanks go to my editor, Jove Belle, the superstar of editors who doesn’t let me get away with anything, even if I beg. And who makes me laugh, which alone is worth the capture of a thousand misplaced commas.

CHAPTER 1

My boss, Shouting Man, had a shit-eating grin plastered on his face, and his voice was uncharacteristically calm.

“Not bad, Sue.” The understatement matched his quiet tone. “That’s a case I never thought we’d settle, let alone with everyone happy.” He nodded towards the office window.

Below, our client was leaving the building with his wife after the mediation in his case. They stopped at the bottom of the steps and our client hugged his wife hard, then the two of them moved away with obvious elation in their strides.

“That’s a good settlement for George Robson,” Shouting Man continued. “We’ll get full fees. You won’t have any issue making budget this month.”

I smiled. It was a good settlement. It was more than good; it was a fantastic one that should certainly merit an article on the company website, and possibly a paragraph in TheLaw Journal.

“Keep this up, and I see a Senior Associate promotion in the very near future for you. We need someone to move up now that Roger’s left. You’re the best we’ve got.” Shouting Man clapped me on the back in a blokey show of appreciation and left my office. Right on cue, I heard him shouting at his P.A. in the corridor.

I exhaled, as much in relief as anything, and tapped a pen against my desk. It was a bloody good settlement. It was an awesome settlement. It was certainly the pinnacle of my career as a lawyer to date. Satisfaction welled inside me.

I got up to push my door closed, and now that I was alone, I indulged in a foot-stomping, fist pumping celebratory dance around my desk. Shouting Man was a senior partner in the firm, and his praise was as infrequent as it was understated. If he was happy, that was as good as it got. Senior Associate. That would not be just a feather in my cap; it would be a whole peacock perched on my head. I performed a very bad moonwalk and another fist pump, and then the door opened to my secretary with a cart of files to put away. She stared wide-eyed at my dance moves. I stopped in mid step, smoothed my hair down, and returned to my desk.

“Should I come back later?” she asked.

“No. It’s fine.” I picked up a random folder and pretended to study it until she left again.

Senior Associate. In a fit of puffed-up pride, I put my feet on the desk, and then promptly took them down again in case anyone else came in. I, Sue Brent, London lawyer. Senior Associate in a reputable firm. That sounded bloody good to me.

It was nearly five, so I took an early mark. I’d earned it. My body fizzed with energy, so I walked instead of taking the tube. London was buzzing, and it fit my mood. Letting my buoyant mood carry me, I pushed my hands into my pockets and fast walked through the throngs of people, past restaurants opening for the evening and pubs that were ready for the after work rush. It was warm and pleasant outside, something I missed about Australia, where I’d grown up. There, so much of life was lived outside—in backyards, camping trips, on horseback, and on the beach. Here in London, it was the polar opposite. Damp and dank weather saw to that, and while the big city had much to offer, outdoor living was not usually a major part.

I walked on, into an area I often frequented with my best friend, Nora, and her wife, Geraldine. There was our favourite Tibetan restaurant. There was the takeaway where we liked to get kebabs after the pubs had shut. And there was the small dyke bar that was Nora’s favourite hangout. I’d spent many evenings there with Nora and Ger, enjoying its intimate environment, designed for conversation rather than casual connections.

I slowed and eventually stopped outside the door. It was open, letting in the warmth of a summer afternoon. I hitched my bag higher on my shoulder. I could easily murder a glass of wine. Red. Rich. Celebratory. The long bar inside, with its row of stools, was mainly empty at this in-between time of day. I’d never been in by myself, so I dithered on the pavement. Going into a pub with friends was different to going in alone. I often went into pubs by myself, sat at the counter, chatted to the barperson, or struck up a conversation with an interesting stranger. Or sometimes I just sat in a corner and read a book. But to go into a lesbian bar alone trod the thin red line of danger, one that I’d been so careful to avoid for nearly ten years.

I walked on, feet dragging on the pavement, but thoughts running fast. What was I scared of? I’d been in that bar dozens of times, and it had always been good fun. I didn’t need to go in with Nora and Ger as my security team. It was a bar. I was being ridiculous. And I really wanted a glass of wine.

I turned on my heel and marched back. The place was nearly deserted. There was an unknown barperson serving, and the only other customers were a loved-up couple in one of the booths at the back and a handsome butch sitting at the counter. I took a stool at the other end of the bar and, eschewing the cheaper plonk we normally ordered, asked for a glass of their very expensive Spanish red. After all, the words “Senior Associate” and “Sue Brent” had never nuzzled up together in the same sentence before. Tonight, I deserved the good stuff.

The wine was amazing. I sipped. I savoured. I was concentrating so hard on the way the colour clung to the glass that when someone spoke to me, I was taken by surprise.

“Seldom have I seen anyone enjoy a glass of wine so much.”

I looked up. The butch had moved to sit next to me. She sat sideways on her stool, her booted heels hooked on the footrest and one hand rested palm up on her thigh.

“I usually buy the cheaper stuff, so I’m determined to enjoy every drop of this. The price they’re charging for it, it won’t be a regular occurrence.”

“So what’s so special this evening?”

I wasn’t ready to share the real reason with a stranger. “Good day at work. Everyone deserves to treat themselves from time to time.”

She picked up her own glass—also red wine—and clinked glasses with me. “Good enough reason.” Her glass was empty after that final mouthful. “Can I buy you another?”

I flicked a glance at her face, but there was only an open sort of friendliness. Nothing that indicated a pick up attempt, nothing except a desire to pass the time. “Thanks,” I said. “I’d like that.”

She signalled the barperson, and two glasses of the Spanish red appeared on the counter. My new friend’s name was Courtney, and she was entertaining company. We chatted about nothing in particular, just a banter back and forth. I returned the shout and bought two more glasses of the same wine, but when they were finished, I decided enough was enough. I was starving and wanted to pick up a curry on the way home to my messy flat, shed my work clothes, and relax in front of the telly. It was only seven; I’d be home in my jammies with my feet up by eight. I’d enjoyed Courtney’s company, her wit, and her quick replies, but it was time for me to head away.

The wine was finished. Courtney arched an eyebrow in question. “Another? Or would you like to go somewhere else?” She tapped her fingers on the bar, very close to my hand.

Her demeanour had changed. Maybe it was the wine; maybe it was our casual rapport. And too, it was a lesbian bar. It wasn’t an unreasonable assumption that a solo woman would be interested in what she was now offering.

“Thanks, but I have to go. Thank you for the wine and conversation.” I gave her a friendly smile. “I’m a bit late already.”

She picked up my hand and held it in hers for a moment as she said, “Can I have your phone number? Maybe we could do something another day?”

My fingers stilled in hers, and then my wall came up. Not slowly, brick by brick, not a gradual shoring up of the defences, but as a slam of finality that dictated my words and actions. I knew what to do, how to handle this. After all, it had happened before. I was on familiar ground.

I removed my fingers from her clasp, slowly, so that she didn’t believe it was a horrified instinct. I hitched my bag higher on my shoulder to give my hands something to do, and I gave her a sincere smile. “Sorry, but I’m straight. Thank you for the wine and the company, but I really do have to go.”

She glanced around the bar, as if to be sure it was still the same dyke pub and that it hadn’t morphed into heterosexuals’ night out while we were talking. Her gaze flicked back to me. She hadn’t taken my words at face value—yet. I gave her another smile. “See you around, Courtney.”

There was a tiny crease between her eyes as she took me in, obviously letting the picture shift away from her interpretation of what had gone before. “Sure,” she said at last. “Thanks for the company. See you, Sue.”

Even if my jammies and the couch hadn’t been calling me, it was now time to leave. I walked out into the street, dragged a deep belly breath to settle myself, and then headed in the direction of home. Deliberately, I put thoughts of the evening out of my head, blotted out Courtney’s face, and instead concentrated on my surroundings, on London—its vibrancy, colour, and excitement. London was indeed a fantastic city. I’d lived here for five years, and it was still as fresh to me as the day I’d arrived. Indeed, if I couldn’t be happy here, where could I be?

And if thoughts of a wide, dry landscape and a slower way of life intruded, well, that was just homesickness. Something to get past. I belonged in London now. Where I was starting to make a real mark on my career. London was friends, and good times. I pushed that red dirt vista firmly out of my head.

I picked up my pace and took the steps down to the tube station two at a time.

CHAPTER 2

It was one of those long evenings that the northern hemisphere does so well. It was nearly nine, and the dying sunlight slanted long and low over the grass. The day had been warm and dry, a perfect British summer Sunday, the sort of day to loll around on a picnic rug, drinking wine, and listening to the lazy thunk of cricket balls as two local teams slogged it out.

I lay on my back and listened to the muted chirping of sparrows and the good natured bickering going on around me. Nora lay perpendicular to me, her feet resting against my leg, her head on Geraldine’s lap. Ger’s brother, Pádraig, was propped on his side, debating with his sister the anticipated outcome of the test match between England and Australia. There were two empty wine bottles, plus our fish and chip wrappers stinking of vinegar in the grass beside us.

I drowsed away in a state of semi-somnolence, half listening to Ger and Pádraig, the rise and fall of their laughing argument just audible over the ever-present hum of London traffic. A sparrow hopped onto my knee and hopped off again when Nora’s twitchy foot sent him flying.

It was the kind of evening I loved best. A quiet time in the company of people who knew me well enough that I could relax. The day’s warmth still lingered, a hint of nature to satisfy my rural Aussie soul. With food and wine in my belly, I was content.

Nora poked me on the hip with a bare toe. “You’re very quiet. What are you thinking?”

I raised my head to squint at her. “Is there more wine?”

“You know there isn’t. And that’s not what you’re really thinking.”

“Why, should I be thinking of anything? I could just be lying here, enjoying the twilight and the company of good friends. Or thinking how stuffed I am from those chips.”

“I know you. You’ve got a strange look on your face as if you’re going to throw up, and you haven’t responded to Pádraig’s digs about the cricket. You’re either asleep or miles away.”

“Asleep then. Enjoying the evening.”

Nora snorted softly. “I can hear your brain ticking from here.”

I opted for silence. Until she called me on it, I would have said I was drowsing or thinking of inconsequential things, such as what to have for lunch tomorrow or what new torture Shouting Man had dreamt up for me now that the shiny good feelings from my settlement of the Robson case had worn off.

As I’d told Nora, I had been thinking how relaxed I was, how nice it was to be in the company of friends. But with Nora’s words came an undercurrent of disquiet. Happiness is composed of such little things, small items stacked one by one on top of each other like building bricks, forming the joy in our lives. And I had that in spades. I should be happy. I was happy. I was officially soon to be Senior Associate happy. But still something nebulous nagged at me, like the first tug of a riptide sucking you away from the beach and safety.

“I’m wondering if I remembered to send back the pre-trial checklist on the Murchison matter.”

Nora, who worked at the same law firm as me, snorted. “Bullshit. And that matter’s not going to trial anytime soon. Not until we’re sure our client’s not lying through his teeth. What are you really thinking?”

Ger and Pádraig were now bickering over the length of the speeches at their mother’s birthday party.

“I’ll be twenty-seven next month,” I said. “I’m thinking it’s time I grew my hair longer, wore my skirts shorter, and started parading around the desperate and dateless bars, waving a vodka martini.”

It was Nora’s turn to raise her head and look at me. “I didn’t expect that answer. I thought you’d say something about your scumbag landlord, or the hopeless secretary you seem to have been saddled with, or even ‘Let’s ditch these two arguing siblings and go and have a drink.’ It’s been ages since we’ve gone out, just the two of us.”

I blinked. “Are you hitting on me?”

Nora’s laugh was low and laced with love. “If I thought you were serious about that, I’d stuff these chip wrappers down your shirt. I never hit on you. Never ever. Even when I wasn’t married to the most wonderful woman in South London.”

“Only South London? Last time you said something like that, it was the most wonderful woman in England.”

Nora waved a hand. “Details, details. Stop putting me off. You know full well I’m not hitting on you. Anyway, straight women are a lot of work.” She winked, but I wasn’t fooled. She hadn’t looked at another woman since she’d met Ger. “It seems like a while since we’ve been out for drinks, just the two of us. Lunches at work don’t count.”

“Yeah.” She was right. It had been a while, a few weeks at least. Nora was my best friend, and I missed our wine-fuelled conversations. Not that I didn’t adore Ger—she was lovely and so perfectly right for my friend—and I genuinely enjoyed her company, but there’s a different dynamic when it’s two best friends and no one else.

I glanced at Ger and Pádraig, now passionately debating the upcoming Wimbledon tennis final. “Fancy a drink now? Those two won’t miss us for an hour.”

“Can’t. We promised Frances we’d go around to sort out the music for her party. I should really cart these arguing siblings away now, or we’ll be there all night. You know how much Frances likes to talk.” Nora sat up and threw one of the chip wrappers at Ger. “Hey, lover, time to go.” Then to me she said, “How about tomorrow after work?”

“No worries.” I heaved myself to my feet and dusted the stray blades of grass from my legs. “I’m away then. See you tomorrow, Nora.” I bent and kissed her cheek and then Ger’s and Pádraig’s.

“See you soon, Sue.” Ger flashed a brilliant smile in my direction. “You still on for Thursday?”

Thursday? My mind went blank, before I remembered—her mother’s birthday party. “Absolutely. I’m looking forwards to it.”

Ger nodded, and beside her, Pádraig flapped a hand in my direction. “See you, Aussie. See you Thursday when I can rub the cricket scores in your face.”

“In your dreams.” I grinned to rub the sting from the words.

I set off across the park in the general direction of my flat. The sun had set, but the long twilight meant there was plenty of light. I was still stuffed from the fish and chips, so I took the long way, passing along residential streets, cutting through the tube station, and around to the busier road. London buzzed around me—traffic and taxis and pubs. This was my city now.

So, why did I suddenly feel so out of place?

I often had lunch with Nora on Mondays, but as we were going out later, we gave it a miss. The day was warm and humid, and I went for a walk instead. The office wasn’t far from the river, so I took my meagre sandwich made of two-day-old bread with cheese and pickle down to the river, and as I ambled along, I watched the Thames flow past in a sluggish brown ribbon.

Maybe it was the summer sunshine, but it seemed there were happy couples everywhere. Two bicycle couriers rode along the path, bikes close together, hands resting on each other’s shoulders. A young couple, barely out of their teens, sat close on a bench and threw crusts for the pigeons. Two pensioners sat on a bench and unwrapped their sandwiches as they overlooked the lazy river, holding hands with their grey heads angled towards each other. They looked as if they had spent the majority of their lives together. I snorted. More likely, they’d met the week before at Drag Queen Bingo in some suburban social club.

I walked along, enjoying the sun on my face. There was a tug in the general vicinity of my heart, brought on by the happy couples. It was as if all my longing and lusting for a partner was being pulled out of me into the sunshine. Sure, I wanted a partner. Hadn’t I spent my time in London dating a string of unsuitable men in my quest to find The One?

Two women went past in the opposite direction, hand in hand. One was tall and lean with a blunt buzz cut, the other more of a classic femme. Superficially, they reminded me of Nora and Ger and their contrasting styles. I turned to watch the women, shoulders bumping as they walked, fingers tightly entwined. I focussed on their hands—female hands, linked together. There was that tug again, stronger now, something deeper, more visceral. I snorted softly. I saw Nora and Ger a couple of times a week at least, and they were one of the most physically demonstrative couples I knew—gay or straight. But seeing the unknown lesbian couple, seeing their closeness and affection… There was that pull again, a reminder of something long buried.

Nora stuck her head into my office just after five. “Ready?”

I shoved the pile of files to one side of my desk and grabbed my bag. We left via a circuitous route that avoided Shouting Man’s office. It wouldn’t be the first time he’d waylaid me with something “urgent” that couldn’t wait until morning. Without debate, we went into the Wellington, an old-fashioned pub that was often quiet and had a small beer garden at the back.

“My round.” Nora disappeared in the direction of the bar, while I wandered out to the beer garden and found a quiet table in the corner.

Nora returned with a bottle of our favourite shiraz and two glasses. The wine was robust and slipped down easily.

For a moment, there was silence, then Nora said, “You better spill. Did you mean what you said yesterday about the singles’ bars?”

Did I mean it? Yes and no. I took another mouthful of wine to buy time before I answered. “Not really. I’m happy enough being single, and I’m far enough away from my parents that there’s no pressure to settle down. Indeed, they’d be upset if I met someone here and stayed in England indefinitely. And who’d have me anyway? They’re not exactly lining up to woo me. I think I’m a better friend than I am partner. Exhibit A: Pádraig.”

Once Nora and Ger committed to each other, they’d needled me into going on a date with each of their brothers. First Nora’s brother, Brian, and then Ger’s brother, Pádraig. They’d been no spark with Brian, even though we’d got on well enough. Pádraig had been more promising. I’d had a couple of good evenings with him, shared some heated kisses, a few caresses, and once, nearly something more. My mind stuttered at that thought and raced away. Pádraig and I were now very good friends. I was almost a Flannery according to Pádraig, as I fitted in so well with him and Ger. The four of us often spent time together, but there was no romance between me and Pádraig.

“I once thought you and Pádraig could have something going.” Nora put down her glass and leant in. “But it seemed to peter out.”

“Like the Aussies’ cricket scores.”

“Seriously, Sue, you never talked about it. But if you want to… It won’t get back to Ger, I promise.”

“It’s not that.”

Nora wasn’t listening. She’d seized on a possible reason for my subdued mood and had raced to a conclusion. “Is that what it is? You’re in love—or lust—with Pádraig, and he only sees you as a friend? What if I asked Ger to—”

“Nope, not that. Not even close.”

Nora frowned. “But the last time Ger mentioned it, she said Pádraig was really keen on you and—”

“You’re on the wrong tram. Pádraig’s a friend, and I love him dearly—as a friend.”

“But there were sparks between you. Early on.”

“Nora, please, drop it. This isn’t about Pádraig. I’m not even sure what it is about.”

She reached across the table and took my hand. The touch was warm and comforting. “Then tell your Auntie Nora. If there’s anything I can do—anything—just tell me.”

I was silent. I wasn’t a talker—not about myself. I’d been told I was a good listener, a solver of other people’s problems, and a fierce and loyal friend. But when it came to me, I couldn’t find the words. Nora was possibly the best friend I’d ever had. She’d seen me through some low periods, and she’d seen me at my drunkest and most obnoxious. But I wasn’t sure I could explain the unsettled feelings I’d been having lately, even to her. But she fixed her gaze on me, her expression earnest, brow furrowed. I sipped my wine and tried to explain.

“It’s not an age thing—twenty-seven isn’t old. It’s not a being-single thing. It’s nothing to do with not having kids. I just feel slightly out of step with the rest of the world. It’s like I’m watching everyone else racing through their lives—going to work, with partners, with friends, playing sport, buying flats, settling down, planning holidays, nesting into their lives.” I took a deep breath and tried to sift through the whirl of thoughts in my head. Nora’s intent expression urged me on.

“It’s as if everyone around me is in sharp focus, and I’m slightly blurry and wavy around the edges, as if I’m not all here. But I don’t know why. I have great friends.” I squeezed her hand, and she squeezed back. “The best friends,” I continued. “I have a job that pays me well, and that I like. I’d like it better if Shouting Man found a long-lost great aunt in Scotland he had to take care of or something, but basically I like it. I’m being made Senior Associate years before I’d dreamt of the possibility. I have people around me who treat me like family—your folks, Ger’s—and I’m never alone unless I want to be. I’m living in London, which is light years from Yeringup, where I grew up. I’m living in one of the best cities in the world, not a backwater in outback Queensland. But I don’t feel like I belong here.”

As I spoke, the words built a picture in my head. Of me, here in London, surrounded by over eight million people, nearly twice as many as lived in the whole of Queensland. Me, rough-around-the-edges, subtle-as-a-hammer, blunt-as-a-bag-of-wet-mice Sue, surrounded by sharp dressing and fast talking Londoners.

And then my thoughts spun me thousands of miles away, down to outback Queensland, where the land stretched flat to the horizon, where there were more kangaroos than people, where the birds wheeled into the sunset like a sail torn loose, where the peace got into your head, wound around your guts, and sucked you in. Birds flocked around a waterhole, noisier than any London nightclub. Timber verandas, with the lazy whop-whop of a ceiling fan turning air so hot and sticky that a person sweated late into the night. The sharp smell of the bush after rain, and the tiny blades of stringy grass pushing up through parched paddocks.

Yeringup, with its single block of commerce, high set Queenslander houses, the two-storey pubs with huge verandas, and the same group of station hands and locals polishing the same long bar with their elbows, putting away beer like water. I sipped the very good shiraz that Nora had bought. In Yeringup, red wine came out of a cask that was kept in the fridge.

I thought of my parents—no doubt still watching the racing on Saturday arvos, going to the pub for the pot and parmie special every Wednesday. A predictable life, one I couldn’t wait to escape growing up. One that I had slipped away from long before I even moved to London.

I’d had my reasons for leaving, and when I did, I thought I wouldn’t be back. I’d jumped on that London-bound flight and was gone. No second guessing; no regret. Indeed, it was as if I’d been given another chance in life, one where no one knew me, and I was able to reinvent myself however I wanted.

Nearly how I wanted.

For the most part, I’d succeeded. But now, sitting in the beer garden, staring at my friend, pieces of my life moved like barrels of a lock, shifting and falling into place. London was my home, but deep down, in the very darkest corners of my mind, were hidden thoughts, ones that came out only when I was alone. I knew that I couldn’t truly start over in a new country until I’d made my peace with the old one.

Suddenly, it was clear. I slid my hand from Nora’s and raised my glass. “A toast,” I said. “I’m going home.”

Nora blinked. “But we just got here. The bottle is nearly full.”

“Not home. Home home. Home to Australia. Home to Queensland. Maybe even home to Yeringup.”

Nora was silent. Surprise was scrawled over her face. She opened her mouth as if to say something, but after a few seconds shut it again, the words unsaid. Eventually she said, “When did you decide this?”

“Just now. I think it’s time.”

“Oh, Sue.” For once, Nora was at a loss for words. Her eyes were suspiciously shiny. “When?”

“I’m not sure. Not immediately. Remember, I’ve only just thought of it. But I think I need to go back to Oz. It’s where I’m from. My roots. My family.”

“But you’ve always said—” Nora shut her mouth with a snap. When did she become as tactless as me? I knew what she had been going to say. She was going to remind me that I’d always said I was a misfit in my family, that they were better at a distance—on the end of an email or the very occasional phone call.

“I’ll need a job over there, and I still have two months’ lease on my flat. I’m sure nothing will happen that quickly.”

Nora pulled herself in, took a deep breath, and once again, she was practical Nora. “Guess I can stop arranging dates for you then. I better call off the posse—Ger’s got some distant cousin lined up to meet you at Frances’s party.”

“Ger’s got more family than the Kennedys.”

Nora shrugged. “Irish Catholics. We can’t help ourselves.”

“Don’t call her off. I’m not gone yet. A nice little dalliance could be just what I need.”

“You’ve said that before. Often. But…”

Her words fell into the air between us and hung there. She was right. I talked the talk, but my attempts at romance were more likely to end in friendship. My last actual boyfriend was a tosser called Leo, and that was nearly three years ago, around the time that Nora met Geraldine. Since then, I’d had several near misses, including Pádraig, but nothing ever eventuated. Sue the celibate.

“Bring on the cousin and tell him to watch out for Sue the man eater.”

“No worries. If that’s what you want.”

“If he’s single, doesn’t have a vindictive ex who is going to appear the next morning to hex me, and has at least an approximation of personality, I’ll be all over him. He won’t know what’s hit him.”

“What if he has five whiny kids who visit on weekends?”

I shrugged. “I don’t plan on being around long enough to meet them. Does he though?”

“I think there’s a couple.”

The wine slid down my throat. “Not my problem. They won’t be in my bed.”

Nora’s intense expression eased, although there was a wistfulness in her eyes that I seldom saw. “I’ll miss you. When you go. You’ve been my best friend.”

“What’s with the past tense? I’m still your best friend. And there’s these amazing inventions called email and the telephone. I even heard there’s these flying machines that can transport people from one side of the world to the other—just like Star Trek, but not quite as fast.”

“Won’t be the same.”

“Will. You’ll have to come and visit. Outback Queensland is nearly ready for you and Ger. Not sure it can support your wine habit though. Ever heard of beer?”

Nora shuddered. “Yes. Doesn’t mean I’m going to drink it anytime soon though.”

The conversation had grown maudlin. I topped up our glasses and changed the subject. “What should I wear to Frances’s party? Something smart and matronly, or my best jeans?”

“I’m wearing jeans, and Ger’s got some floaty boho tie-dye dress that looks amazing on her.”

“Ger could wear court documents stapled together, and you’d think she looked amazing. Jeans it is. I’m glad you said that. Matronly won’t do if I’m to seduce Ger’s distant cousin. Did I tell you what I’ve got Frances for her birthday?”

Nora shook her head. “No, but I’m sure you’re going to.”

“A DVD of The Full Monty.”

Nora laughed. “She’ll be horrified. Men taking their clothes off! Should only happen behind closed doors.”

“She’ll love it. She once confessed to me that she wanted to watch it but was too embarrassed to rent it from the DVD shop.”

“Hasn’t she heard of the online places?”

“Apparently not. I’ve also got her some really expensive tea from Thailand. Picked with the first bloom of frost, according to the packet. Let’s see if I can get her off that terrible tea from County Cork you all drink.”

The bottle was empty. Nora picked it up and tried to wring a few more drops from it. “Another?”

“No.” I slid from the stool. “I’ll let you get back to Ger, and I’ll see you tomorrow at work anyway.”

She followed suit, and we hugged.

“Thanks for talking.” I released her and stepped back.

“You mean it?”

“About going back to Oz? Yeah. I do. Although I’ll probably come running back in six months.”

The long London evening was sliding into darkness when we left the pub. It was a couple of miles to my flat, but I decided to walk. I wanted to think about what had rolled out of my mouth earlier. Going back to Oz. I hadn’t given any thought to that idea before this evening.

It would be easy to dismiss it as a bout of homesickness brought about by too much wine. I’d had the pangs of longing for a wide, flat vista and a well-trodden veranda before, but they were just that—pangs. They lasted no longer than a couple of minutes and a chorus of Waltzing Matilda. Even now, as I paced the busy street, dodging the teenagers hunched in their hoodies, I had a longing to be somewhere else. Somewhere quieter. Somewhere I belonged.

Deliberately, I set my thoughts to those things about home that were less than pleasurable. The drunken heckling at closing time of any woman under fifty. The lack of arts and culture that I so loved here in London. There were no art galleries, café culture, or music events within five hundred kilometres of Yeringup. Sure, the major cities had an abundance of those, but those cities were two days’ drive away and there was no budget airline to fly me there for five quid, bring-your-own sandwich and dunny roll. I thought of the insular community and the conservative values that still held sway. Ah yes, those bloody values. My thoughts skittered away from that. I wasn’t ready to go there yet.

Just like an old ABBA song, other things kept sneaking into my head and wouldn’t be dislodged. Matched up against the trials of life in a too-small town was a caring community, where people looked out for each other, where simple things could bring such pleasure. The feel of a good horse between your thighs, and the excitement of polocrosse. Driving up a dusty road to home. Cold beer in the fridge and a wide comfy couch for sitting. Taking too long to get the groceries because you’d had four conversations in the shop with people you knew. A dog. A little ripper of a working dog by your side. I missed having a dog—it simply wasn’t possible with my London lifestyle. Those things wound through my guts and pulled tight until I was breathless with the longing for home.

I turned a corner into the busier street and increased my pace as I passed the takeaways, the pubs, and the convenience stores. London surrounded me with its noise, its ever-present hum, and people. Always people. I’d loved living here. Loved it for all the things I didn’t have in Queensland. But by the time I turned into my road and unlocked the door of my flat, my mind was made up. Like Frank-N-Furter from The Rocky Horror Picture Show blasting back to transsexual Transylvania, I was going home.

CHAPTER 3

The next thing I had to do was tell people—family back in Oz and friends in London and elsewhere.

I composed a few emails and sent them winging on their way. My brother responded with his usual verboseness—Good-oh! You owe me a beer! My mother was more forthcoming, but reading between the lines of her rather stilted email, it seemed as if she didn’t quite know how to react, as if she wouldn’t believe I was coming home until I rolled in the back door and started rummaging in the fridge. My dad added a PS that read Looking forwards to seeing you, love Dad.

My family was not known for long and rambling correspondence.

It was easier to write to friends. A couple of friends from university, now scattered around Australia. Nobody from Yeringup.

And Moni.

I’d met Moni three years ago, just before Nora had committed to Ger. Moni was an American tourist that Nora had met—I was never quite sure how, or where, but knowing Nora, it was probably a one-night stand. Nora had been quite the player before she hooked up with Ger. I’d spent a day with Nora and Moni, having breakfast, going to the Tower of London, and having a good time generally. Moni was a small woman with a huge smile and a mass of blonde hair that fell in waves halfway down her back. I loved her humour, her energy, and her determination to make the most of her short time in London.

At the time, Nora had told her I was straight. That was a given—Nora told everyone I was straight. And it seemed everyone believed it. Moni, however… She’d looked at me with her piercing blue eyes, really looked at me, her head cocked slightly to one side. We were having breakfast, and I remembered her slight smile as her gaze held mine. “I see you, sista,” her gaze had said. “You can’t hide from me.”

The three of us had spent a great day together, and then we had parted ways. And Moni had kissed me.

It was just a kiss. She’d just kissed Nora goodbye, and it had lingered slightly. The sort of kiss one lesbian gives another if they’re a little more than friends, or at least, if there had been that possibility. Then she’d turned to me. “See you around, Sue,” she’d said, and then she’d kissed me too. On the lips. They’d been soft, and tasted slightly bitter from the Guinness she’d been drinking. Just for a second, she’d leant into the kiss, daring me to take it forwards. Daring me to kiss her properly.

And I had been tempted.

It had only lasted a couple of seconds, and then she’d pulled away. There was a slight smile on her lips, but she hadn’t said anything. Then she was gone.

Had Nora seen how Moni’s lips had lingered on mine? Probably not. She’d pigeonholed me into the straight box long ago, and if she’d noticed, she’d probably put it down to the outgoing American.

Moni and I had kept in touch. Chatty emails from time to time. The occasional Skype. She told me about her medical studies, her graduation as a doctor, and then her attempts to find the sort of medical job that she really wanted. Somewhere rural, she said. She was a country girl at heart, and her time in Dallas had been fun, but it was time to move on. It sounded a bit like how I felt about London. From time to time, she talked about a date she’d had with some woman or the other—she didn’t seem to be in a relationship.

I talked about work, nights out with friends, titbits about Nora and Ger—in particular, I’d sent photos of their wedding—and humorous accounts of their attempts to set me up with one or the other of their brothers.

But there was more to it. I wanted to keep the connection going with Moni for reasons that went beyond a casual long-distance friendship. That breakfast with Nora and Moni, the day we’d spent together, had been good. It had been fun.

It had been dangerous.

It had been dangerous because, if Moni had remained in London, I would have run. Run away and retreated before anything could happen between us. She was the first woman who had rocked the image I presented to the world. Sorry-I’m-Straight Sue moved aside for those few hours I’d spent with her, to allow for the possibility of Not-So-Straight Sue. And because Moni was in Texas, on the end of an email, and not someone I’d meet in the flesh again in London, I allowed myself to keep that friendship going, to savour it. I’d read each of her emails over again, visualising her writing them with her quick smile and quicker wit. I’d relived the time spent in her company more times than I cared to think about.

So Moni was an obvious person to tell my news to. I buried it in a chatty email that meandered through a few subjects—including the weather—before I got to the point.

I’m returning to Australia. Yeah, I know I’ve said I love it here in London (and I do), but something is dragging me home. Don’t ask me to put a finger on it, because I can’t. It’s probably just good old homesickness. I guess it bites us all in the end. So, once I’ve given notice at my job, my flat, found a job down under, sold everything I own, bought everything again, and basically uplifted my life from this tiny patch of land with sixty-four million people, to a very large patch with only twenty-four million, then I’ll be set.

She replied the next day.

Congratulations you! Didn’t expect that. I thought big news from you might mean you’d found the love of your life. But I guess you (like me) are still looking for that someone. Your email made me smile (but, hey, girlfriend, YOU make me smile), and I may, just might, just maybe, have some big news of my own to share in a few weeks. Wish me luck!

I replied, wishing her all the luck in the world for her mysterious project, and then she slipped from my head as I threw myself into preparations for departure.

Of course, nothing happened in an instant. I needed to save money, book flights, give notice at my job, and sift through the detritus of five years in London. Mixed in with all of that, I made sure I enjoyed London life to the fullest. I never turned down an invitation to go out with friends, and I went on a lot of dates, but only ever one time. If I turned a bloke down for a second date, well, that was because he wasn’t my type.

“You’re too bloody picky,” Nora said to me one lunchtime as we ate our sandwiches by the Thames. “They’re either too old, too young, too fat, too rich, too drug-addicted, too thin, too weird, too nerdy, or too ordinary. I’m honestly not sure what you want any more.”

“Ger makes the world’s greatest sangers. The least you can do is share.” I traded half of my ham and salad for half of Nora’s tandoori chicken.

“Stop changing the subject. But if you’re taking half my sandwich, I want half your Mars Bar.”

“Deal.”

“But seriously, Sue, are you really looking for someone in all of these dates you’re going on, or are you deliberately picking the wrong types? You’ve always disliked the prep school mentality of rugby players, but you dated two of them in the last month alone.”

“Maybe I’m broadening my horizons. And they have great thighs.”

“Unless you’re holding out on me, you haven’t seen their thighs.”

“I’ve got a great imagination. That’s why I’m a lawyer.”

Nora snorted. “That’s like saying sharks are great vegetarians. Talking of lawyers, how’s the job hunt going?”

I swallowed the last bite of sandwich, pulled the Mars Bar out of its wrapper, broke it in two, and handed half to Nora. “Not great. Nobody is taking me seriously because I’m in London and job hunting in Queensland. I may have to wait until I get there, which will do serious damage to my finances.”

“What about in the capital cities?”

“Nope. No cities. If I’m going back to Oz, it’s to a rural area. I’m now looking at the larger inland towns.” I sighed. “I thought it would be easy—that the small rural firms would snap me up, great London lawyer that I am, especially given that most Aussies want to be in the cities earning the big bucks. I’ve still got a few applications out there though, and a month before I leave.”

“You’ll get something. Besides, you need to be in a position to offer your old friend a paralegal job for a couple of months if Ger and I come and visit.”

Stupid tears pricked behind my eyes. “You’re the best bloody friend I’ve ever had. I’m going to miss you.”

“You won’t say that in a few weeks when you’re whooping it up in Oz.”

“I will. I’ll miss our lunches. The quiet evenings with you and Ger. I’ll even miss Pádraig, Brian, and your and Ger’s enormous families.”

“I’ll trade you my sister Mary for a dingo in a dress anytime. At least a dingo wouldn’t bang on about its pregnancy and prenatal vitamins for hours at a time.”

I changed the subject before Nora could climb onto her soapbox. “Actually, I did get one expression of interest in hiring me. A one-person practice in outback Queensland. The principal wants to go around Australia in his motorhome and is looking for someone to hold the fort for a year while he’s gone.”

“That’s great! Where’s the town?”

“It’s a tiny practice in a small town, nearly on the Northern Territory border. The practice is mainly wills and estates, conveyancing, some litigation—motor vehicle accidents and the like. A bit of family law. It’s mainly law I know nothing about as I haven’t done anything except litigation in years. On the plus side, it’s kept Ken—the current lawyer—occupied for nearly thirty years and given him enough money to buy a snazzy motorhome. He’s really keen to meet me—probably because no one else is remotely interested.”

“When would you have to be there?”

“That’s one good thing. There’s no set start date. As long as I’m there at some point in the next three months, he’s happy. He’d give me a couple of weeks handover, leave me the keys to his house, sole control of his practice and his wine collection—his words, not mine. There’s even a housekeeper, whom I’d have to retain as he doesn’t want to lose her.”

“That doesn’t sound so bad. Rather good actually. You said you wanted to live rural. And you hate housework—you can’t even keep your flat tidy. How far away is it from Yeringup?”

“About seven hundred kilometres. One long, hot day’s drive.”

“Bloody hell. I could be in the South of France in seven hundred kilometres. But that’s good, right? Close enough to be there if you want to be, far enough away that your mum won’t be dropping in for a cuppa and a chat every day.”

I chewed my Mars Bar in silence for a minute. “That’s just it. If I’m going back—and I am—I want to be within a day’s drive from Yeringup. I think it’s time to stop running. Time to go home. Even if it’s difficult.”

Nora groped for my hand and gave it a hard squeeze. Her palm was hot and dry. “You’ve never told me about your home. Not really. I’ve gleaned enough to know you have a good reason for leaving in the first place. But you know I’m always here to listen.”

I squeezed back. “Thank you. It’s a long and overwrought story of teenage angst and misunderstanding. Nothing to get excited about.”

“You’re the least melodramatic person I know. Coming from anyone else, your story would probably be headlines in the Sunday rag.”

For a moment, I was tempted to confide in Nora. If I couldn’t share my story with her, well, there wasn’t anyone else. But I resisted. Once I started talking, I wasn’t sure I would be able to stop, and we had to be back at work in fifteen minutes.

“I’m tempted to find out more about the job,” I said instead. “I can always turn it down.”

Nora laughed. “Then I better book my ticket to… Where did you say it was?”

“It’s called Mungabilly Creek.” As I said it, the name settled into my bones, as if it had always been a part of me. I liked the feel of it on my tongue. It sounded like home.

CHAPTER 4

Nora and Ger wanted to throw me a big farewell party, but I managed to talk them out of it. After all, I’d had the leaving-work-morning-tea, the leaving-work-after-work-drinks, the farewell-from-the-netball-team, and the goodbye-dinner-from-Legal-Aid where I volunteered once a month. That pretty much covered it as far as friends went. Instead, the night before I flew to Oz, Nora, Ger, Pádraig, and I went out to dinner. I was staying with Nora and Ger that night as I’d moved out of my flat and given away or shipped all my belongings. I had what I stood up in, and a backpack of stuff to take on the plane.

I’d taken the job at Mungabilly Creek. At times, I could hardly believe I had. I was going to be living in a town a little smaller than Yeringup, with one pub, a takeaway, a general store, and a petrol station. Ken, the sole practitioner I’d be standing in for, sounded like a genuinely nice bloke, who was looking forwards to his trip around Australia in his motorhome. As long as I arrived in the next couple of months, he was happy. His cheerful attitude and certainty that I would be the perfect person to babysit his practice had convinced me.

The four of us went to my favourite Vietnamese restaurant and ate pho and rice paper rolls until we were too stuffed to move. It was a surprisingly chilly September night, and the restaurant was warm and snug, so we lingered over more wine and ate desserts that none of us really wanted in order to avoid going out in the damp night. Eventually, Nora and Ger went off to settle the bill, leaving me at the table with Pádraig.

For a few moments there was silence. A comfortable sort of quiet that neither of us felt the immediate urge to fill. Eventually Pádraig spoke.