9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

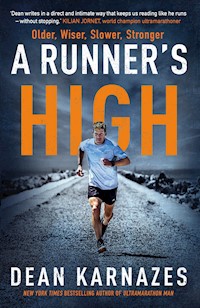

Dean Karnazes has pushed his body and mind to inconceivable limits, from running in the shoe-melting heat of Death Valley to the lung-freezing cold of the South Pole. He's raced and competed across the globe and once ran 50 marathons, in 50 states, in 50 consecutive days. In A Runner's High, Karnazes chronicles his return to the Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run in his mid-fifties after first completing the race decades ago. The Western States, infamous for its rugged terrain and extreme temperatures, becomes the most demanding competition of his life, a physical and emotional reckoning and a battle to stay true to one's purpose. Confronting his age, wearying body, career path and life choices, we see Karnazes as we never have before, raw and exposed. A Runner's High is both an endorphin-fuelled page-turner and a love letter to the sport from one of its most celebrated ambassadors.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

DEAN KARNAZES is an icon in the running world. He was named by TIME magazine as one of the ‘100 Most Influential People in the World.’ An internationally acclaimed endurance athlete, he’s the winner of an ESPN ESPY, 3-time winner of Competitor magazine’s Endurance Sports Athlete of the Year, and recipient of the President’s Council on Sports, Fitness & Nutrition Lifetime Achievement award. And to boot, he’s run around the world naked (true story!). He lives in San Francisco with his family.

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Allen & Unwin

First published in the United States in 2021 by HarperCollins Publishers

Copyright © 2021 by Dean Karnazes

The moral right of Dean Karnazes to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Allen & Unwin

c/o Atlantic Books

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

Phone: 020 7269 1610

Fax: 020 7430 0916

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN 978 1 83895 381 2

Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 83895 382 9

E-Book ISBN 978 1 83895 383 6

Printed in

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to my mother and father—to the times we’ve had, the memories we’ve created, and the joy we’ve shared. It’s been a fantastic journey. Together forever.

CONTENTS

1 ENDURANCE NEVER SLEEPS

2 GROWING PAINS

3 WHY WE RUN

4 FOLLOW THE PATH

5 CAN’T STOP; WON’T STOP

6 THE AFTERMATH

7 THE SILK ROAD ULTRA

8 THE LONG RUN

9 CHASING WINDMILLS

10 FRIENDSHIP AND FATHERHOOD

11 LOST IN A WHITE HOUSE

12 JUST DID IT

13 THE CAVS AND THE CAVS-NOTS

14 TO CUT IS TO HEAL

15 BACK TO THE START

16 LET’S GET THIS PARTY STARTED

17 LOOSE LUG NUTS

18 THE SILLY AND THE SUBLIME

19 THE MELTDOWN

20 HEAD FAKE

21 EMBRACE THE SUCK

22 LONDON CALLING

23 THE LIGHT

CONCLUSION: NEW WORLD DISORDER

GRATITUDE

1

ENDURANCE NEVER SLEEPS

Running an ultra is simple; all you have to do is not stop.

I’m lying catawampus splayed ass-to-the-dirt in the trail—one leg tweaked improbably beneath me—staring up at the afternoon sky seeing sparkles of light flickering before me like circling fireflies and wondering what the hell just happened. A sharp ringing in my ears perforates the otherwise complete stillness, a lazy film of dust rising indolently around my idle carcass. Inside the motor room my muscles and bodily organs register a dull tenderness, but it is the nausea that is most pronounced, a queasy sensation of being punched hard in the gut. What just happened?

Moments ago I was in perfect harmonic flow, bounding along nicely, cool and in control, step, spring, step . . . Then everything changed. I vaguely recall flight, weightless soaring, a defiant middle finger to gravity as time briefly suspended; my wings spread—fly, be free . . .

Until impact. Kaboom! Everything just exploded, like a skydiver whose chute failed to deploy. Now I’m heaped on the soil like Icarus, a lifeless, charred exoskeleton smoldering in ruin and wondering what just went down. A ticker tape of questions scroll across the screen of my mind: Is anything broken? Will someone find me? Where am I?

To answer that final question we need to dial back the clock to yesterday morning, a time when I had a sinking premonition: I shouldn’t be doing this. I REALLY shouldn’t be doing this. I know better. Then I shut the door behind me. I was doing it.

At least the timing of my departure seemed good. The merciless Bay Area traffic was showing its gentler side and I slipped through the busiest corridors with barely a tap on the brakes. Sometimes it takes hours just getting across town, and when it comes to sucking the living soul out of a creature, perhaps no human creation is more noxious than traffic (with the exception of TSA lines).

Still, despite the absence of congestion, it took nearly eight hours to reach my destination, the juxtaposed pastoral hamlet of Bishop, California. Nestled under the striking peaks of the Eastern Sierra Nevada mountain range, Bishop is something of a conundrum. It’s in a beautiful natural setting, though one oddly frequented equally by hikers and bikers (and the bikes they’re riding aren’t the kind with pedals). The main street through town has quaint galleries, outdoor mountaineering stores, a nature center, and an indie bookstore, things you might expect in a mountain settlement. But then there are rows of fast-food joints, seedy bars, a collection of budget hotels, and a Kmart, all of which thoroughly taper the city’s charm with a liberal dousing of contemptible.

I was meeting my father here, at one such establishment of lesser repute. Unfortunately, there was little choice in the matter; it was the only remaining hotel room in town. Reservations were made last minute and I booked what I could get. As would be expected on such short notice, there also weren’t many options for securing a crew to help support my endeavor, though I somehow snagged the very best (i.e., dear ol’ Dad). Who else would drop everything on a single two-minute phone call and drive six hours from Southern California to meet me? There hasn’t been a more loyal companion in my life than my father.

A spry eighty-two years old, the man bounced about like a loosely attached valence electron careening haphazardly around its outer shell. Sparks flew off him, a perpetual fission reaction capable of erupting with no forewarning. He was electric, charismatic, overwhelming at times, and wholly uncontainable. Every moment with him was slightly unpredictable. The older he grew the more lively his personality became. Laughter, angst, melancholy, joy—all of these emotions could be expressed within the confines of a single brief interaction. You never knew what to expect with Dad.

“ULTRAMARATHON MAN!” he boomed when he saw me (I’d asked him not to call me that a thousand times, but it was no use). A reporter had tagged me with that lovely moniker and I’d never felt comfortable with it. But over time it had taken on a life of its own, especially with my dad!

“Hiya, Pops,” I said, hugging him. “How was the drive?”

“Piece of cake.” He was fond of clichés.

“So you good?” I asked.

“Never had a bad day.”

Just wait until tomorrow, I thought coyly.

My mother was usually part of these far-flung escapades. The two were nearly inseparable. Sixty years of wedlock had brought them closer, two old-fashioned romantics clinging tightly through all of life’s crazy turbulence. Since their retirement they were in a state of perpetual motion. They’d toured just about every part of North America, Australia, and much of Europe. Sometimes on a whim they’d fly to Greece for a month or two with no fixed plans, no itinerary, no accommodations, nothing but a rental car (and rental cars in Greece are not always the most dependable machines). “Things work out,” my mother always tells me. She wasn’t here today because of a 5K she’d scheduled along the beach with her buddies, most of whom were decades younger. They still couldn’t keep up. She wasn’t fast, but my mother had the gift of endurance. From the Greek island of Ikaria—one of the fabled “Blue Zones” where indigenous people routinely live beyond a hundred—she is freakishly indefatigable, especially when it comes to outdoor adventures. Mom would certainly be with us today if she weren’t showing up those young lasses back home.

The air in Bishop is different than in San Francisco. In the Bay Area, even when you can’t see the water you can still smell its thick, salty dampness. In Bishop the air is hot and arid, a subtle hint of a smoldering campfire permanently hangs in the atmosphere. You could feel it in your eyes, the gritty dryness, and in your sinuses. Bishop sits in the high desert, in the lee of an imposing mountain range. Incoming storms lose their moisture as they sweep across California, and any rainfall left as they progress inland is mostly deposited along the western slopes of the uprising. Perilously little water makes it over the towering granite impediment of the Sierra Nevada. On average, Bishop receives about five inches of rainfall annually, and summertime humidity can drop into the single digits. Think of it as having a hair dryer ceaselessly blowing instead of an encroaching fog bank.

Although now well into the afternoon, the sun still seared my skin as I walked to the office to collect our room keys. The official start to summer wasn’t for a few weeks, but you’d never know it. The heat coming off the pavement radiated through my shoes, warming and swelling my feet. Tomorrow was supposed to be even hotter.

A small wall-mounted air-conditioning unit was noisily sputtering in the corner when I entered, but it was simply no match for the elements. It was stifling inside, even though the shades were drawn and it was dark. The innkeeper used a handkerchief to pat the sweat off his forehead. The place reeked of Lysol and dirty socks. I asked if there was an ice machine. “There is,” he told me. “But it’s busted.”

The elevator was busted, too. Thus we carried our bags up to our second-story chalet. “Sorry about these accommodations.”

“They’re fine,” my dad offered up, “just fine.”

Staying in the room next to us were two fully grown pit bulls. I was told the hotel was “pet-friendly,” but two adult pit bulls hardly seemed like sociable pets to me. The owners didn’t appear very genial, either. Standing outside having a cigarette, they looked us over with suspicion.

And we, for our part, were quick to get in our room and shut the door behind us. Once inside, the place was musty and dank. “We should probably check for bedbugs,” I bemoaned, hoisting our bags into the closet. But when I pulled open the blinds to let in some light the view out the dusty window instantly carried me someplace else, someplace special and expansive, a familial place that was part of my very constitution. Beams of late-afternoon sunlight extended heavenward, the jagged silhouette of the Sierra Nevada perched in the distance like an Ansel Adams photograph, towering columns of marble white clouds rising into the air and the sky so impossibly deep, dark blue. I’d been coming here most my life, since Dad and I first climbed Mount Whitney—the highest peak in the conterminous United States—when I was twelve years old. We carried heavy metal-framed packs and slept in a thick canvas tent, our hiking boots and wool socks left outside to air out. We cooked pouches of freeze-dried food over a small camp stove and rationed water from our canteens until we could find another brook to refill them. During the day we hiked, eating leathery beef jerky and trail mix, my fingers colorfully dyed with the melted coating of M&Ms. Sometimes we talked, but mostly we just hiked, swept up in the grand enormity of the surroundings, the brilliant artistry of Mother Nature holding us spellbound. When we reached the summit I humbly signed the logbook, forever marking my presence on this hallowed mountain peak.

I wasn’t a very good student, but my writing assignment about the Eastern Sierra trip with Dad got an A plus. It was my first A plus ever, and the teacher had plastered the report with a bunch of those colorful smiley-face stickers. They were stuck all over it, colorful little dots, and it made me joyful seeing all those smiley faces, a warm, flush feeling inside.

I loved those days, and I loved those adventures. I could let my long, wavy hair go uncombed. Nobody told me I couldn’t go there or I couldn’t do that; out here I was the master of my own destiny, free to wander as I pleased, free to explore. We didn’t have much when I was a boy, we had everything. We had the Eastern Sierra, Yosemite, and Sequoia. We had the San Gabriels and San Jacinto. We had Joshua Tree and Death Valley, Tahoe and Desolation Wilderness. We had Big Sur and the Pinnacles, Mendocino and the Redwoods in the north, Shasta in the middle, and Lassen to the east. We had California wild and untamed, and every summer vacation, every spring break, every school holiday and long weekend, we’d pack up the lime-green Ford Country Squire station wagon (replete with wood panels) and head for the trails. We were Outside magazine before there was Outside magazine.

Tomorrow I’d be setting out to relive some of those memories and to create some new ones. I’d returned to run the Bishop High Sierra Ultramarathon and my dad and I were together once again, a team reunited. Older now, yes, but still together. Still carrying on.

The Bishop High Sierra Ultramarathon offered four race distances: 20 miles, 50 kilometers, 50 miles, and 100 kilometers. “I’m not in any shape to run 100 kilometers,” I told Dad.

“So which race did you sign up for?” he asked.

“The 100 kilometers.”

Of course I did. “I shouldn’t be doing this,” I said to him. “I know better.”

“This isn’t your first rodeo, cowboy.”

“Yeah, I guess you’re right. I’ve done some stupid shit before.”

“C’mon, ultramarathon man, you know what you’re up against,” he said, patting me on the back.

“Yeah, I do know what I’m up against. And that’s what scares me.”

What I was up against was 62 miles of climbing and descending a narrow dirt path through the mountains and desert of the High Sierra in the blazing heat. I knew full well what I was up against. But another battle awaited me before I even reached the starting line.

“I’ll set the alarm for three thirty.”

“Three thirty! Why so early? The race doesn’t start till five thirty.”

“You don’t want to be late.”

“Dad, it’s a five-minute drive.”

“You want to have time to warm up?”

“Warm up? I’ll have 62 miles to warm up.”

“Suppose there’s traffic?”

“Dad, this is Bishop, population 3,760. The only way there’d be traffic is if there’s an earthquake.”

“Suppose there is?”

“AHH! You’re exhausting.”

Arguing with Dad could be more draining than running an ultramarathon. One of his most vigorously defended positions has to do with promptness. In my opinion he takes it too far. For instance, if he has an appointment scheduled—say, at the DMV—he would make it a point to arrive at least an hour early, just to be on the safe side. Now, I’m not sure about you, but if I found myself with a spare hour to burn, waiting at the DMV wouldn’t top my priority list. But there was no use arguing with the man.

“Okay, Pops, set your alarm for three thirty.”

“Great. We’ll have some coffee.”

We both looked up at the chintzy in-room coffeemaker. There were two Styrofoam cups, a generic Mylar bag stamped Supreme Coffee, and a couple of pink packets of artificial sweetener. Yum.

“Do you see a socket over there?” he inquired.

I looked behind the table separating our beds. “There’s one right here.”

“Could you plug this in?” He handed me the extension cord from his CPAP machine.

“You’re gonna wear that thing tonight?”

“Doc says I should use it every night.” The CPAP is an apparatus used to treat sleep apnea. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) uses a hose and head mask to enhance nighttime breathing, and there’s a small water chamber that adds moisture to the airflow. When he had it on he looked like Hannibal Lecter and sounded like a deep-sea diver. All night long this rhythmic gurgling gently serenaded me, like a lapping tide ebbing and flowing. It was as though I were sleeping on a dock.

The chiming of the three thirty alarm was inconsequential. I hadn’t slept much all night, not with Aquaman bubbling away next to me. But that was fine; endurance never sleeps.

Splashing some water on my face over the bathroom sink, I peered at myself through the yellowy light. I shouldn’t be doing this, I thought. I haven’t been training; I know better. I rubbed my fingers through my hair. Let’s do this.

There wasn’t much activity when we arrived at the starting area, which was a large open park with a lake in the middle, the reflection of the moon rippling on its surface. Gradually dawn began to emerge and a crowd slowly gathered. All of the race distances—20 miles, 50K, 50 miles, and 100K—started at the same time, and more and more racers began appearing. In the assemblage I saw a few familiar faces, Billy Yang being one of them.

“Karno! How’s it going, bro?”

“Hey, Billy, nice to see you.”

“You’re the reason I’m here, dude. Don’t you ever forget that.”

“I’m just glad we’re still friends.”

He laughed. Billy credited me as one of the forces behind his journey into ultramarathoning. He’d read one of my earlier books and decided to give it a go. A fresh young face in the mix, it was good to see him.

“You running the 100K?” I asked.

“No way, dude. The 50K. I haven’t been training. I know better.”

Doh! How someone with less experience than I had could somehow be wiser was a quandary of ongoing internal debate. Consistently biting off more than I could chew and wantonly hurling myself into waters over my head were parts of my primary source code, repeating themes. Perhaps I subconsciously thrilled at the possibility of shit going wrong. Look, I’m just as unstirred by life as the next guy. Modern existence is so comfortably predictable, so ho-hum, so, well, boring. But this was different. With an ultramarathon the outcome was never certain, and when things unraveled they truly fell apart. It elevated having a bad day at the office to unprecedented heights. And I lived for it.

The race director stepped to the front of the group to say a few parting words. He warned us to stay hydrated, as it was going to be hot and dry today. He alerted us to watch for trail markers to avoid getting lost. Again he cautioned us to stay hydrated.

There were 181 runners at the start. Old-timers lament about the unfettered growth and mainstream popularity of today’s ultrarunning scene. Out of control, they say. The previous year’s New York City marathon had more than 55,000 registered participants. I’d say the sport of ultrarunning still had a bit of growth left, not that I’m taking sides in the matter. I see both points. When I first started this crazy sport, if fifty people showed up for a race it was a pretty good turnout. Nowadays some ultramarathons sell out, and there are even lotteries to get in. Blasphemy!

I stepped to the side of the pack to say good-bye to Dad. “Keep your nose clean, kid,” he counseled. He’d been giving me this same advice for most my life. I still had no idea what it meant.

“Thanks, Pops. Will do.”

The countdown commenced. “. . . four, three . . .” I made a cross on my chest. “. . . two, one . . .” The starting gun fired and the pack surged forward. Church was now in session.

I established my position squarely in the thick of the lead pack and fixed my gaze on two sets of muscular calves in front of me, running in tight formation with a cluster of others somewhere near the head of the herd. The initial terrain was relatively flat and groomed, so the pace was hasty, the starting line adrenaline still working its way through the system. A spiraling cloud of dust arose in the still morning air like a wildebeest stampede crashing forth with frenzied urgency.

This lasted for all of about 5 miles. Then the incline steepened, and maintaining such a rushed cadence became unsustainable if not impossible. My lungs stretched to full capacity yet still couldn’t deliver enough oxygen to propel my legs at that same clip. Hence, I slowed. Over the next 15 miles the course would gain about five thousand feet of elevation. For perspective, the notorious Heartbreak Hill at the Boston Marathon rises less than a hundred feet. An ultramarathon is a different sort of monster.

And ultramarathoners are different sorts of creatures. Instead of seeking flat and fast courses, we look for the hilliest and most challenging ones. Speed matters, but the elevation gain and loss of a particular race are equal badges of honor. The legendary Hardrock 100, for instance, has 33,050 feet of climbing and descending, for a total elevation change of 66,100 feet. That’s the equivalent of running from sea level to the summit of Mount Everest and back, plus a warm-up and a cool-down.

Ultramarathoners abide by a different dress code, too (or irreverence for one). Mismatched colors are commonplace. Vibrant crew socks, Day-Glo arm sleeves, funky trucker hats, retro eyewear—nothing is too outlandish. The same goes for tats, hair color, piercings, and beards. They’re commonplace. Though as far as I’m concerned, if you’ve got the guts and the discipline to be running an ultramarathon you can pretty much wear whatever the hell you want.

At the 15-mile mark I was feeling light and nimble. At 20 miles I was feeling light-headed with a slight ring in my ears. I knew this feeling and knew the cause. Twenty-four hours ago I was a sea dweller, living and sleeping in the thickest air possible. Now I was ninety-four hundred feet up in the air. The altitude was doing its thing.

Standing at the Overlook aid station trying to gather my senses, another two runners came bounding in. We exchanged nods, and began foraging for morsels of food spread about the small camping table.

“How you feeling?” the gentleman asked.

He was youthful-looking and solid as oak. There was a woman running with him; she looked equally buff.

“I’m a bit light-headed, honestly. You guys?”

He smiled sheepishly. “We live in Lake Tahoe.”

While he didn’t answer my question directly, his meaning was implicit. They lived at altitude and they were coping just fine, as breezily as walking to the end of the driveway to fetch the morning paper. Off they went. I capped my water bottle and strode along after them.

The course had followed a rugged jeep road for much of the distance thus far, but now it meandered through high-desert chaparral in a series of broad switchbacks and rolling ascents and descents. The 20-miler and 50K runners had split off from the 50-mile and 100K runners by this point and were now on their return journey while we still had many miles to go. With the separation of the two groups there were noticeably fewer people on the course and I found myself running solo, no fellow humans in sight.

There’d been a few pine trees interspersed at the higher elevations, but here there was absolutely no shade along the course. I’d opted to go with a handheld water bottle instead of a larger hydration pack. It was a strategic decision. Running in a slightly depleted state was part of my master plan to hack my training.

You see, I needed to seriously accelerate my fitness because of some news I’d recently received. Good news, for sure, but also worrisome. Worrisome to the point that immediate action was required, hence the hasty registration for a tough 100K, the quick drive to Bishop, and the decision to carry only one handheld water bottle (and an uninsulated one at that). I shouldn’t be doing this, but here I was.

And thus I kept doing it. Mile 20 passed. Mile 23 passed. Mile 26 passed. Running an ultra is simple; all you have to do is not stop.

Bishop Creek was the first place I rendezvoused with Dad. It was mile 29 and by now the sun was perched firmly overhead, and scorching. Crewing for someone during an ultramarathon can best be described as rushing around from one place to the next, only to sit and wait. Some people are better cut out for this duty than others. Dad was extremely well adept. He could make friends with anyone, anywhere. I remember a telemarketer once calling our house trying to sell him life insurance. Dad turned the conversation around and ended up selling the guy our used car. And he wrote Dad a thank-you letter. The man was just that likable.

And did I mention prompt? Yes, I did. And to prove my point, he’d been waiting at the Bishop Creek aid station for hours, just rapping out with people and making friends, and trying to stay in the shade. But even in the shade it was broiling. Still, he had a beach chair set up, and all my gear spread out on a towel for easy access.

“Hey, Pops,” I said, running into the aid station. “It’s hot.”

“It’s not too bad. Whaddya need?”

“An air conditioner would be nice.”

He took off his hat and started fanning me.

Dad would do anything for his family. Never did he complain or act put out by a request. He was always there, always available. Growing up, he attended all of my games, though I can’t say I always appreciated his presence. Some of my friends’ fathers never came to theirs. I didn’t understand the magnitude of Dad’s loyalty back then. Now I do. Family matters; family matters more than all else.

“Say Pops, is that ginger around?”

Ginger is the miracle elixir for gut issues, which is a frequent ailment afflicting long-distance runners, especially when temperatures elevate. Many ultramarathoners chew on candied ginger. I preferred my tonic straight.

Dad handed me a container of freshly sliced ginger. I stuck a piece in my mouth and immediately felt the burn. I encourage you to try this at home (over the sink). Few people can deal. Candied ginger is spicy; straight ginger is the equivalent of tossing live firecrackers into your mouth.

I winced.

Pops looked at me concerned. “I don’t know how you do that.”

“Whatever works, right?”

He shrugged his shoulders and gave me a doubtful look.

We filled my water bottle and sprayed some additional sunscreen on the back of my neck. As I was leaving, another runner came springing in. He looked young and strong. When he saw me he did a double take. Was he competitive? Did I now have a target on my back?

It was hard to know where anyone stood in the race at this point. Of the few runners I periodically saw it wasn’t entirely clear if they were running the 50-miler or the 100K; both of us currently ran on the same course. By this point the pack had thinned considerably and there wasn’t much passing or being passed going on; everyone had pretty much established his or her position and was holding his or her own. And as helpful as the volunteers were, they didn’t have much information about race standings.

I’ve never been much of a competitive runner. Sure, I enjoy the thrill and high drama of competition, but I don’t live for it. To me, running is a grand adventure, an intrepid outward exploration of the landscape and a revealing inward journey of the self. These are the things that keep me going, the lust for exploration and the quest to better comprehend who I am and what I’m made of. In a lifetime’s worth of competition, there’s only been one race I explicitly set out to win, the 2004 Badwater Ultramarathon (which I was fortunate enough to actually win). Other than that, running and racing has been an experiential trip, not a desire to end up on the podium.

Still, when someone is hunting you down, you don’t want to be passed. Consequently, when I left the aid station I kicked up the pace a notch to avoid capture. The next several miles to the Intake aid station were run aggressively, perhaps too aggressively. It was a short distance; that was the rationale behind my recklessness (that, and not being passed). But when I arrived at the Intake aid station—32 miles from the start—I was suddenly feeling the ramifications. I’d crossed the midpoint but was feeling right about done. That warm, rewarding, semifried, halfway-finished feeling was more akin to something fully charred, like lamb smoldering over an open spit. Suddenly it felt hot. Unbearably hot. Roasting hot. I was cooked, yet still had plenty of course yet to cover.

“Dad, who turned up the furnace?”

He gave me a look like You think it’s hot out there running, try standing around this aid station for an hour. All of the volunteers looked wilted. There was just one small umbrella set up over the food table, and everyone scrunched together trying to fit under the minuscule shadow it cast.

My original goal at this aid station was to relax and gather my wits—I was feeling a bit loopy—but it was clear this wasn’t the place to do it. Consequently, my mission shifted from getting to the aid station to getting out of the aid station just as fast as I could, both for me and Dad. We refilled my water bottle and I grabbed a packet of nut butter, then off I set . . . just as that younger runner was pulling in.

The gap between us had narrowed.