8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

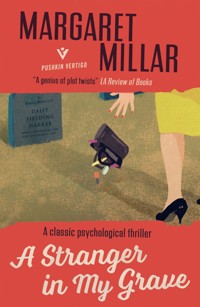

A nightmare becomes a terrifying reality in this rediscovered classic of American noir from one of crime writing's greatest talents A nightmare is haunting Daisy Harker. Night after night she walks a strange cemetery in her dreams, until she comes to a grave that stops her in her tracks. It's Daisy's own, and according to the dates on the gravestone she's been dead for four years. What can this nightmare mean, and why is Daisy's husband so insistent that she forget it? Driven to desperation, she hires a private investigator to reconstruct the day of her dream death. But as she pieces her past together, her present begins to fall apart... Margaret Millar (1915-1994) was the author of 27 books and a masterful pioneer of psychological mysteries and thrillers. Born in Kitchener, Ontario, she spent most of her life in Santa Barbara, California, with her husband Ken Millar, who is better known by his nom de plume of Ross Macdonald. Her 1956 novel Beast in View won the Edgar Allan Poe Award for Best Novel. In 1965 Millar was the recipient of the Los Angeles Times Woman of the Year Award and in 1983 the Mystery Writers of America awarded her the Grand Master Award for Lifetime Achievement. Millar's cutting wit and superb plotting have left her an enduring legacy as one of the most important crime writers of both her own and subsequent generations.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR MARGARET MILLAR AND HER WORK

“In the whole of crime fiction’s distinguished sisterhood, there is no one quite like Margaret Millar”

GUARDIAN

“One of the most original and vital voices in all of American crime fiction”

LAURA LIPPMAN, AUTHOR OF SUNBURN

“She has few peers, and no superior in the art of bamboozlement”

JULIAN SYMONS, THE COLOUR OF MURDER

“Mrs Millar doesn’t attract fans, she creates addicts”

DILYS WINN

“She writes minor classics”

WASHINGTON POST

“Very original”

AGATHA CHRISTIE

“One of the pioneers of domestic suspense, a standout chronicler of inner psychology and the human mind”

SARAH WEINMAN, AUTHOR OF THE REAL LOLITA AND EDITOR OF WOMEN CRIME WRITERS: EIGHT SUSPENSE NOVELS OF THE 1940S & 50S

“The real queen of suspense… She can’t write a dull sentence, and her endings always deliver a shock”

CHRISTOPHER FOWLER, AUTHOR OF THE BRYANT & MAY MYSTERIES

“Margaret Millar is ripe for rediscovery. Compelling characters, evocative settings, subtle and ingenious plots – what more could a crime fan wish for?”

MARTIN EDWARDS, AUTHOR OF THE LAKE DISTRICT MYSTERIES

“No woman in twentieth-century American mystery writing is more important than Margaret Millar”

DOROTHY B HUGHES, AUTHOR OF IN A LONELY PLACE

“Margaret Millar can build up the sensation of fear so strongly that at the end it literally hits you like a battering ram”

BBC

“Millar was the master of the surprise ending”

INDEPENDENT ON SUNDAY

“Clever plot… and a powerful atmosphere”

THE TIMES

“A brilliant psychodrama that has a triple-whammy ending… exhilarating”

EVENING STANDARD

“Conjures up images from Edward Hopper paintings with characters that keep secrets from each other… The terse prose pushes the story along to a shock reveal”

SUNDAY TIMES CRIME CLUB

“This subtle, psychological crime thriller crackles with tension and keeps you guessing until the end… A hypnotic novel… Ideal fireside reading”

THE LADY

“It doesn’t get more noir than this”

DAILY MAIL

“Millar is a fine writer and this novel is a well-honed thriller that will appeal to any serious noir fan… damned good”

NUDGE NOIR

“Superb writing, superb plotting… bloody marvelous”

COL’S CRIMINAL LIBRARY

“Millar is a brilliant plotter, hooking red herrings left, right and centre, but proves just as sharp at character, grim humour and smart description”

SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST

“Wickedly smart 1950s crime novel… great characters, genius plot and a thoroughly good read”

THRILLER BOOKS JOURNAL

“A superbly plotted tale of murder and deception”

RAVEN CRIME READS

This book is dedicated, with affection and admiration, to Louise Doty Colt

Contents

THE GRAVEYARD

1

My beloved Daisy: It has been so many years since I have seen you…

The times of terror began, not in the middle of the night when the quiet and the darkness made terror seem a natural thing, but on a bright and noisy morning during the first week of February. The acacia trees, in such full bloom that they looked leafless, were shaking the night fog off their blossoms like shaggy dogs shaking off rain, and the eucalyptus fluttered and played coquette with hundreds of tiny gray birds, no bigger than thumbs, whose name Daisy did not know.

She had tried to find out what species they belonged to by consulting the bird book Jim had given her when they’d first moved into the new house. But the little thumb-sized birds refused to stay still long enough to be identified, and Daisy dropped the subject. She didn’t like birds anyway. The contrast between their blithe freedom in flight and their terrible vulnerability when grounded reminded her too strongly of herself.

Across the wooded canyon she could see parts of the new housing development. Less than a year ago, there had been nothing but scrub oak and castor beans pushing out through the stubborn adobe soil. Now the hills were sprouting with brick chimneys and television aerials, and the landscape was growing green with newly rooted ice plant and ivy. Noises floated across the canyon to Daisy’s house, undiminished by distance on a windless day: the barking of dogs, the shrieks of children at play, snatches of music, the crying of a baby, the shout of an angry mother, the intermittent whirring of an electric saw.

Daisy enjoyed these morning sounds, sounds of life, of living. She sat at the breakfast table listening to them, a pretty dark-haired young woman wearing a bright blue robe that matched her eyes, and the faintest trace of a smile. The smile meant nothing. It was one of habit. She put it on in the morning along with her lipstick and removed it at night when she washed her face. Jim liked this smile of Daisy’s. To him it indicated that she was a happy woman and that he, as her husband, deserved a major portion of the praise for making and keeping her that way. And so the smile, which intended no purpose, served one anyway: it convinced Jim that he was doing what at various times in the past he’d believed to be impossible—making Daisy happy.

He was reading the paper, some of it to himself, some of it aloud, when he came upon any item that he thought might interest her.

“There’s a new storm front off the Oregon coast. Maybe it will get down this far. I hope to God it does. Did you know this has been the driest year since ’48?”

“Mmm.” It was not an answer or a comment, merely an encouragement for him to tell her more so she wouldn’t have to talk. Usually she felt quite talkative at breakfast, recounting the day past, planning the day to come. But this morning she felt quiet, as if some part of her lay still asleep and dreaming.

“Only five and a half inches of rain since last July. That’s eight months. It’s amazing how all our trees have managed to survive, isn’t it?”

“Mmm.”

“Still, I suppose the bigger ones have their roots down to the creek bed by this time. The fire hazard’s pretty bad, though. I hope you’re careful with your cigarettes, Daisy. Our fire insurance wouldn’t cover the replacement cost of the house. Are you?”

“What?”

“Careful with your cigarettes and matches?”

“Certainly. Very.”

“Actually, it’s your mother I’m concerned about.” By looking over Daisy’s left shoulder out through the picture window of the dinette, he could see the used-brick chimney of the mother-in-law cottage he’d built for Mrs. Fielding. It was some 200 yards away. Sometimes it seemed closer, sometimes he forgot about it entirely. “I know she’s fussy about such things, but accidents can happen. Suppose she’s sitting there smoking one night and has another stroke? I wonder if I ought to talk to her about it.”

It was nine years ago, before Jim and Daisy had even met, that Mrs. Fielding had suffered a slight stroke, sold her dress shop in Denver, and retired to San Félice on the California coast. But Jim still worried about it, as if the stroke had just taken place yesterday and might recur tomorrow. He himself had always had a very active and healthy life, and the idea of illness appalled him. Since he had become successful as a land speculator, he’d met a great many doctors socially, but their presence made him uncomfortable. They were intruders, Cassandras, like morticians at a wedding or policemen at a child’s party.

“I hope you won’t mind, Daisy.”

“What?”

“If I speak to your mother about it.”

“Oh no.”

He returned, satisfied, to his paper. The bacon and eggs Daisy had cooked for him because the day maid didn’t arrive until nine o’clock lay untouched on his plate. Food meant little to Jim at breakfast time. It was the paper he devoured, paragraph by paragraph, eating up the facts and figures as if he could never get enough of them. He’d quit school at sixteen to join a construction crew.

“Now here’s something interesting. Researchers have now proved that whales have a sonar system for avoiding collisions, something like bats.”

“Mmm.” Some part of her still slept and dreamed: she could think of nothing to say. So she sat gazing out the window, listening to Jim and the other morning sounds. Then, without warning, without apparent reason, the terror seized her.

The placid, steady beating of her heart turned into a fast, arrhythmic pounding. She began to breathe heavily and quickly, like a person engaged in some tremendous physical feat, and the blood swept up into her face as if driven before a wind. Her forehead and cheeks and the tips of her ears burned with sudden fever, and sweat poured into the palms of her hands from some secret well.

The sleeper had awakened.

“Jim.”

“Yes?” He glanced at her over the top of the paper and thought how well Daisy was looking this morning, with a fine high color, like a young girl’s. She seemed excited, as if she’d just planned some new big project, and he wondered, indulgently, what it would be this time. The years were crammed with Daisy’s projects, packed away and half forgotten, like old toys in a trunk, some of them broken, some barely used: ceramics, astrology, tuberous begonias, Spanish conversation, upholstering, Vedanta, mental hygiene, mosaics, Russian literature—all the toys Daisy had played with and discarded. “Do you want something, dear?”

“Some water.”

“Sure thing.” He brought a glass of water from the kitchen. “Here you are.”

She reached for the glass, but she couldn’t pick it up. The lower part of her body was frozen, the upper part burned with fever, and there seemed to be no connection between the two parts. She wanted the water to cool her parched mouth, but the hand on the glass would not respond, as if the lines of communication had been broken between desire and will.

“Daisy? What’s the matter?”

“I feel—I think I’m—sick.”

“Sick?” He looked surprised and hurt, like a boxer caught by a sudden low blow. “You don’t look sick. I was thinking just a minute ago what a marvelous color you have this morning—oh God, Daisy, don’t be sick.”

“I can’t help it.”

“Here. Drink this. Let me carry you over to the davenport. Then I’ll go and get your mother.”

“No,” she said sharply. “I don’t want her to—”

“We have to do something. Perhaps I’d better call a doctor.”

“No, don’t. It will all be over by the time anyone could get here.”

“How do you know?”

“It’s happened before.”

“When?”

“Last week. Twice.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

“I don’t know.” She had a reason, but she couldn’t remember it. “I feel so—hot.”

He pressed his right hand gently against her forehead. It was cold and moist. “I don’t think you have a temperature,” he said anxiously. “You sound all right. And you’ve still got that good healthy color.”

He didn’t recognize the color of terror.

Daisy leaned forward in her chair. The lines of communication between the two parts of her body, the frozen half and the feverish half, were gradually re-forming themselves. By an effort of will she was able to pick up the glass from the table and drink the water. The water tasted peculiar, and Jim’s face, staring down at her, was out of focus, so that he looked not like Jim, but like some kind stranger who’d dropped in to help her.

Help.

How had this kind stranger gotten in? Had she called out to him as he was passing, had she cried, “Help!”?

“Daisy? Are you all right now?”

“Yes.”

“Thank God. You had me scared for a minute there.”

Scared.

“You should take regular daily exercise,” Jim said. “It would be good for your nerves. I also think you haven’t been getting enough sleep.”

Sleep. Scared.Help. The words kept sweeping around and around in her mind like horses on a carousel. If there were only some way of stopping it or even slowing it down—hey, operator; you at the controls, kind stranger, slow down, stop, stop, stop.

“It might be a good idea to start taking vitamins every day.”

“Stop,” she said. “Stop.”

Jim stopped, and so did the horses, but only for a second, long enough to jump right off the carousel and start galloping in the opposite direction, sleep and scared and help all running riderless together in a cloud of dust. She blinked.

“All right, dear. I was only trying to do the right thing.” He smiled at her timidly, like a nervous parent at a fretful, ailing child who must, but can’t, be pleased. “Listen, why don’t you sit there quietly for a minute, and I’ll go and make you some hot tea?”

“There’s coffee in the percolator.”

“Tea might be better for you when you’re upset like this.”

I’m not upset, stranger. I’m cold and calm.

Cold.

She began to shiver, as if the mere thinking of the word had conjured up a tangible thing, like a block of ice.

She could hear Jim bumbling around in the kitchen, opening drawers and cupboards, trying to find the tea bags and the kettle. The gold sunburst clock over the mantel said 8:30. In another half hour the maid Stella would be arriving, and shortly after that Daisy’s mother would be coming over from her cottage, brisk and cheerful, as usual in the mornings, and inclined to be critical of anyone who wasn’t, especially Daisy.

Half an hour to become brisk and cheerful. So little time, so much to do, so many things to figure out. What happened to me? Why did it happen? I was just sitting here, doing nothing, thinking nothing, only listening to Jim and to the sounds from across the canyon, the children playing, the dogs barking, the saw whirring, the baby crying. I felt quite happy, in a sleepy kind of way. And then suddenly something woke me, and it began, the terror, the panic. What started it, which of those sounds?

Perhaps it was the dog, she thought. One of the new families across the canyon had an Airedale that howled at passing planes. A howling dog, when she was a child, meant death. She was nearly thirty now, and she knew some dogs howled, particular breeds, and others didn’t, and it had nothing to do with death.

Death. As soon as the word entered her mind, she knew that it was the real one; the others going around on the carousel had been merely substitutes for it.

“Jim.”

“Be with you in a minute. I’m waiting for the kettle to boil.”

“Don’t bother making any tea.”

“How about some milk, then? It’d be good for you. You’re going to have to take better care of yourself.”

No, it’s too late for that, she thought. All the milk and vitamins and exercise and fresh air and sleep in the world don’t make an antidote for death.

Jim came back, carrying a glass of milk. “Here you are. Drink up.”

She shook her head.

“Come on, Daisy.”

“No. No, it’s too late.”

“What do you mean it’s too late? Too late for what?” He put the glass down on the table so hard that some of the milk splashed on the cloth. “What the hell are you talking about?”

“Don’t swear at me.”

“I have to swear at you. You’re so damned exasperating.”

“You’d better go to your office.”

“And leave you here like this, in this condition?”

“I’m all right.”

“O.K., O.K., you’re all right. But I’m sticking around anyway.” He sat down, stubbornly, opposite her. “Now, what’s this all about, Daisy?”

“I can’t—tell you.”

“Can’t, or don’t want to? Which?”

She covered her eyes with her hands. She was not aware that she was crying until she felt the tears drip down between her fingers.

“What’s the matter, Daisy? Have you done something you don’t want to tell me about—wrecked your car, overdrawn your bank account?”

“No.”

“What, then?”

“I’m frightened.”

“Frightened?” The word displeased him. He didn’t like his loved ones to be frightened or sick; it seemed to cast a reflection on him and his ability to look after them properly. “Frightened of what?”

She didn’t answer.

“You can’t be frightened without having something to be frightened about. So what is it?”

“You’ll laugh.”

“Believe me, I never felt less like laughing in my life. Come on, try me.”

She wiped her eyes with the sleeve of her robe. “I had a dream.”

He didn’t laugh, but he looked amused. “And you’re crying because of a dream? Come, come, you’re a big girl now, Daisy.”

She was staring at him across the table, mute and melancholy, and he knew he had said the wrong thing, but he couldn’t think of any right thing. How did you treat a wife, a grown woman, who cried because she had a dream?

“I’m sorry, Daisy. I didn’t meant to—”

“No apology is necessary,” she said stiffly. “You have a perfect right to be amused. Now we’ll drop the subject if you don’t mind.”

“I do mind. I want to hear about it.”

“No. I wouldn’t like to send you into hysterics; it gets a lot funnier.”

He looked at her soberly. “Does it?”

“Oh yes. It’s quite a scream. There’s nothing funnier than death, really, especially if you have an advanced sense of humor.” She wiped her eyes again, though there were no fresh tears. The heat of anger had dried them at their source. “You’d better go to your office.”

“What the hell are you so mad about?”

“Stop swearing at—”

“I’ll stop swearing if you’ll stop acting childish.” He reached for her hand, smiling. “Bargain?”

“I guess so.”

“Then tell me about the dream.”

“There’s not very much to tell.” She lapsed into silence, her hand moving uneasily beneath his, like a little animal wanting to escape but too timid to make any bold attempt. “I dreamed I was dead.”

“Well, there’s nothing so terrible about that, is there? People often dream they’re dead.”

“Not like this. It wasn’t a nightmare like the kind of dream you’re talking about. There was no emotion connected with it at all. It was just a fact.”

“The fact must have been presented in some way. How?”

“I saw my tombstone.” Although she’d denied that there was any emotion connected with the dream, she was beginning to breathe heavily again, and her voice was rising in pitch. “I was walking along the beach below the cemetery with Prince. Suddenly Prince took off up the side of the cliff. I could hear him howling, but he was out of sight, and when I whistled for him, he didn’t come. I started up the path after him.”

She hesitated again. Jim didn’t prompt her. It sounded real enough, he thought, like something that actually happened, except that there was no path up that cliff and Prince never howled.

“I found Prince at the top. He was sitting beside a gray tombstone, his head thrown back, howling like a wolf. I called to him, but he paid no attention. I went over to the tombstone. It was mine. It had my name on it. The letters were distinct, but weathered, as if it had been there for some time. It had.”

“How do you know?”

“The dates were on it, too. Daisy Fielding Harker, it said. Born November 13, 1930. Died December 2, 1955.” She looked at him as if she expected him to laugh. When he didn’t, she raised her chin in a half-challenging manner. “There. I told you it was funny, didn’t I? I’ve been dead for four years.”

“Have you?” He forced a smile, hoping it would camouflage his sudden feeling of panic, of helplessness. It was not the dream that disturbed him; it was the reality it suggested: someday Daisy would die, and there would be a genuine tombstone in that very cemetery with her name on it. Oh God, Daisy, don’t die. “You look very much alive to me,” he said, but the words, meant to be light and airy, came out like feathers turned to stone and dropped heavily on the table. He picked them up and tried again. “In fact, you look pretty as a picture, to coin a phrase.”

Her quick changes of mood teased and bewildered him. He had never reached the point of being able to predict them, so he was completely unprepared for her sudden, explosive little laugh. “I went to the best embalmer.”

Whether she was going up or coming down, he was always willing to share the ride. “You found him in the Yellow Pages, no doubt?”

“Of course. I find everything in the Yellow Pages.”

Their initial meeting through the Yellow Pages of the telephone directory had become a standard joke between them. When Daisy and her mother had arrived in San Félice from Denver and were looking for a house to buy, they had consulted the phone book for a list of real-estate brokers. Jim had been chosen because Ada Fielding was interested in numerology at the time and the name James Harker contained the same number of letters as her own.

In that first week of taking Daisy and her mother around to look at various houses, he’d learned quite a lot about them. Daisy had put up a great pretense of being alert to all the details of construction, drainage, interest rates, taxes, but in the end she picked a house because it had a fireplace she fell in love with. The property was overpriced, the terms unsuitable, it had no termite clearance, and the roof leaked, but Daisy refused to consider any other house. “It has such a darling fireplace,” she said, and that was that.

Jim, a practical, coolheaded man, found himself fascinated by what he believed to be proof of Daisy’s impulsive and sentimental nature. Before the week was over, he was in love. He deliberately delayed putting the papers for the house through escrow, making excuses which Ada Fielding later admitted she’d seen through from the beginning. Daisy suspected nothing. Within two months they were married, and the house they moved into, all three of them, was not the one with the darling fireplace that Daisy had chosen, but Jim’s own place on Laurel Street. It was Jim who insisted that Daisy’s mother share the house. He had a vague idea, even then, that the very qualities he admired in Daisy might make her hard to handle at times and that Mrs. Fielding, who was as practical as Jim himself, might be of assistance. The arrangement had worked out adequately, if not perfectly. Later, Jim had built the canyon house they were now occupying, with separate quarters for his mother-in-law. Their life was quiet and well run. There was no place in it for unscheduled dreams.

“Daisy,” he said softly, “don’t worry about the dream.”

“I can’t help it. It must have some meaning, with everything so specific, my name, the dates—”

“Stop thinking about it.”

“I will. It’s just that I can’t help wondering what happened on that day, December 2, 1955.”

“Probably a great many things happened, as on any day of any year.”

“To me, I mean,” she said impatiently. “Something must have happened to me that day, something very important.”

“Why?”

“Otherwise my unconscious mind wouldn’t have picked that particular date to put on a tombstone.”

“If your unconscious mind is as flighty and unpredictable as your conscious mind—”

“No, I’m serious about it, Jim.”

“I know, and I wish you weren’t. In fact, I wish you’d stop thinking about it.”

“I said I would.”

“Promise?”

“All right.”

The promise was as frail as a bubble; it broke before his car was out of the driveway.

Daisy got up and began to pace the room, her step heavy, her shoulders stooped, as if she were carrying the weight of the tombstone on her back.

2

Perhaps, at this hour that is very late for me, I should not step back into your life…

Daisy didn’t watch the car leave, so she had no way of knowing that Jim had stopped off at Mrs. Fielding’s cottage. The first suspicion occurred to her when her mother, who was constantly and acutely aware of time, appeared at the back door half an hour before she was due. She had Prince, the collie, with her on a leash. When the leash was removed, Prince bounced around the kitchen as if he’d just been released after a year or two in leg-irons.

Since Mrs. Fielding lived alone, it was considered good policy for her to keep Prince, a zealous and indefatigable barker, at her cottage every night for protection. Because of this talent for barking, he enjoyed the reputation of being an excellent watchdog. The fact was, Prince’s talent was spread pretty thin; he barked with as much enthusiasm at acorns falling on the roof as he would have at intruders bursting in the door. Although Prince had never been put to a proper test so far, the general feeling was that he would come through when the appropriate time arrived, and protect his people and property with ferocious loyalty.

Daisy greeted the dog affectionately, because she wanted to and because he expected it. The two women saw each other too frequently to make any fuss over good-mornings.

“You’re early,” Daisy said.

“Am I?”

“You know you are.”

“Ah well,” Mrs. Fielding said lightly, “it’s time I stopped living by the clock. And it was such a lovely morning, and I heard on the radio that there’s a storm coming, and I didn’t want to waste the sun while it lasted—”

“Mother, stop that.”

“Stop what, for goodness’ sake?”

“Jim came over to see you, didn’t he?”

“For a moment, yes.”

“What did he tell you?”

“Oh, nothing much, actually.”

“That’s no answer,” Daisy said. “I wish the two of you would stop treating me like an idiot child.”

“Well, Jim made some remark about your needing a tonic, perhaps, for your nerves. Oh, not that I think your nerves are bad or anything, but a tonic certainly wouldn’t do any harm, would it?”

“I don’t know.”

“I’ll phone that nice new doctor at the clinic and ask him to prescribe something loaded with vitamins and minerals and whatever. Or perhaps protein would be better.”

“I don’t want any protein, vitamins, minerals, or anything else.”

“We’re just a mite irritable this morning, aren’t we?” Mrs. Fielding said with a cool little smile. “Mind if I have some coffee?”

“Go ahead.”

“Would you like some?”

“No.”

“No, thanks, if you don’t mind. Private problems don’t constitute an excuse for bad manners.” She poured some coffee from the electric percolator. “I take it there are private problems?”

“Jim told you everything, I suppose?”

“He mentioned something about a silly little dream you had which upset you. Poor Jim was very upset himself. Perhaps you shouldn’t worry him with trivial things. He’s terribly wrapped up in you, Daisy.”

“Wrapped up.” The words didn’t conjure up the picture they were intended to. All Daisy could see was a double mummy, two people long dead, wrapped together in a winding sheet. Death again. No matter which direction her mind turned, death was around the corner or the next bend in the road, like a shadow that always walked in front of her. “It wasn’t,” Daisy said, “a silly little dream. It was very real and very important.”

“It may seem so to you now while you’re still upset. Wait till you calm down and think about it objectively.”

“It’s quite difficult,” Daisy said dryly, “to be objective about one’s own death.”

“But you’re not dead. You’re here and alive and well, and, I thought, happy… You are happy, aren’t you?”

“I don’t know.”

Prince, with the sensitivity of his breed to a troubled atmosphere, was standing in the doorway with his tail between his legs, watching the two women.

They were similar in appearance and perhaps had had, at one time, some similarity of temperament. But the circumstances of Mrs. Fielding’s life had forced her to discipline herself to a high degree of practicality. Mr. Fielding, a man of great charm, had proved a fainthearted and spasmodic breadwinner, and Daisy’s mother had been the main support of the family for many years. Mrs. Fielding seldom referred to her ex-husband, unless she was very angry, and she never heard from him at all. Daisy did, every now and then, always from a different address in a different city, but with the same message: Daisy baby, I wonder if you could spare a bit of cash. I’m a little low at the moment, just temporarily, I’m expecting something big any day now… Daisy, without informing her mother, answered all the letters.

“Daisy, listen. The maid will be here in ten minutes.” Mrs. Fielding never called Stella by name because she didn’t approve of her. “Now’s our chance to have a little private talk, the kind we always used to have.”

Daisy was aware that the private little talk would eventually become a rather exhaustive survey of her own faults: she was too emotional, weak-willed, selfish, too much like her father, in fact. Daisy’s weaknesses invariably turned out to be duplications of her father’s.

“We’ve always been so close,” Mrs. Fielding said, “because there were just the two of us together for so many years.”

“You talk as if I never had a father.”

“Of course you had a father. But…”

There was no need to go on. Daisy knew the rest of it: Father wasn’t around much, and he wasn’t much when he was around.

Silently Daisy turned and started to go into the next room. Prince saw her coming, but he didn’t budge from the doorway, and when she stepped over him, he let out a little snarl to indicate his disapproval of her mood and the way things were going in general. She reprimanded him, without conviction. She’d had the dog throughout the eight years of her marriage, and she sometimes thought Prince was more conscious of her real emotions than Jim or her mother or even herself. He followed her now into the living room, and when she sat down, he sat down, too, putting one paw in her lap, his brown eyes staring gravely into her face, his mouth open, ready to speak if it could: Come on, old girl, cheer up. The world’s not so bad. I’m in it.

Even when the maid arrived at the back door, usually an occasion for loud and boisterous conduct, Prince didn’t move.

• • •

Stella was a city girl. She didn’t like working in the country. Though Daisy had explained frequently and patiently that it took only ten minutes to drive from the house to the nearest supermarket, Stella was not convinced. She knew the country when she saw it, and this was it, and she didn’t like it one bit. All that nature around, it made her nervous. Wasps and hummingbirds coming at you, snails sneaking about, bees swarming in the eucalyptus trees, fleas breeding in the dry soil, every once in a while taking a sizable nip out of Stella’s ankles or wrists.

Stella and her current husband occupied a second-floor apartment in the lower end of town where all she had to cope with was the odd housefly. In the city, things were civilized, not a wasp or snail or bird in sight, just people: shoppers and shopkeepers by day, drunks and prostitutes at night. Sometimes they were arrested right below Stella’s front window, and occasionally there was a knife fight, very quick and quiet, among the Mexican nationals relaxing after a day of picking lemons or avocados. Stella enjoyed these excitements. They made her feel both alive (all those things happening) and virtuous (but not to her. No prostitute or drunk, she; just a couple of bucks on a horse, in the back room of the Sea Esta Café every morning before she came to work).

While the Harkers were still living in town, Stella was content enough with her job. They were nice people to work for, as people to work for went, never snippy or mean-spirited. But she couldn’t stand the country. The fresh air made her cough, and the quietness depressed her—no cars passing, or hardly ever, no radios turned on full blast, no people chattering.

Before entering the house, Stella stepped on three ants and squashed a snail. It was the least she could do on behalf of civilization. Those ants sure knew they was stepped on, she thought, and pushed her two hundred pounds through the kitchen door. Since neither Mrs. Harker nor the old lady was around, Stella began her day’s labors by making a fresh pot of coffee and eating five slices of bread and jam. One nice thing about the Harkers, they bought only the best victuals and plenty of.

“She’s eating,” Mrs. Fielding said in the living room. “Already. She hardly ever does anything else.”

“The last one was no prize either.”

“This one’s impossible. You should be firmer with her, Daisy, show her who’s boss.”

“I’m not sure I know who’s boss,” Daisy said, looking faintly puzzled.

“Of course you do. You are.”

“I don’t feel as if I am. Or want to be.”

“Well, you are, whether you want to be or not, and it’s up to you to exercise your authority and stop being willy-nilly about it. If you want her to do something or not to do something, say so. The woman’s not a mind reader, you know. She expects to be told things, to be ordered around.”

“I don’t think that would work with Stella.”

“At least try. This habit of yours—and it is a habit, not a personality defect as I used to believe—this habit of letting everything slide because you won’t take the trouble, because you can’t be bothered, it’s just like your—”

“Father. Yes. I know. You can stop right there.”

“I wish I could. I wish I’d never had to begin in the first place. But when I see quite unnecessary mismanagement, I feel I must do something about it.”

“Why? Stella’s not so bad. She muddles through, and that’s about all you can expect of anyone.”

“I don’t agree,” Mrs. Fielding said grimly. “In fact, we don’t seem to be agreeing on anything this morning. I don’t understand what the trouble is. I feel quite the same as usual—or did, until this absurd business of a dream came up.”

“It’s not absurd.”

“Isn’t it? Well, I won’t argue.” Mrs. Fielding leaned forward stiffly and put her empty cup on the coffee table. Jim had made the table himself, of teakwood and ivory-colored ceramic tile. “I don’t know why you won’t talk to me freely anymore, Daisy.”

“I’m growing up, perhaps that’s the reason.”

“Growing up? Or just growing away?”

“They go together.”

“Yes, I suppose they do, but—”

“Maybe you don’t want me to grow up.”

“What nonsense. Of course I do.”

“Sometimes I think you’re not even sorry I can’t have a child, because if I had a child, it would show I was no longer one myself.” Daisy paused, biting her lower lip. “No, no, I don’t really mean that. I’m sorry, it just came out. I don’t mean it.”

Mrs. Fielding had turned pale, and her hands were clenched in her lap. “I won’t accept your apology. It was a stupid and cruel remark. But at least I realize now what the trouble is. You’ve started thinking about it again, perhaps even hoping.”

“No,” Daisy said. “Not hoping.”

“When are you going to accept the inevitable, Daisy? I thought you’d become adjusted by this time. You’ve known about it for five whole years.”

“Yes.”

“The specialist in Los Angeles made it very clear.”

“Yes.” Daisy didn’t remember how long ago it was, or the month or the week. She only remembered the day itself, beginning the first thing in the morning when she was so ill. Then, afterward, the phone call to a friend of hers who worked at a local medical clinic: “Eleanor? It’s Daisy Harker. You’ll never guess, never. I’m so happy I could burst. I think I’m pregnant. I’m almost sure I am. Isn’t it wonderful? I’ve been sick as a dog all morning and yet so happy, if you know what I mean. Listen, I know there are all sorts of obstetricians in town, but I want you to recommend the very best in the whole country, the very, very best specialist…”

She remembered the trip down to Los Angeles, with her mother driving. She’d felt so ecstatic and alive, seeing everything in a fresh new light, watching, noticing things, as if she were preparing herself to point out all the wonders of the world to her child. Later the specialist spoke quite bluntly: “I’m sorry, Mrs. Harker. I detect no signs of pregnancy…”

This was all Daisy could bear to hear. She’d broken down then, and cried and carried on so much that the doctor made the rest of his report to Mrs. Fielding, and she had told Daisy: there were to be no children ever.

Mrs. Fielding had talked nearly all the way home while Daisy watched the dreary landscape (where were the green hills?) and the slate-gray sea (had it ever been blue?) and the barren dunes (barren, barren, barren). It wasn’t the end of the world, Mrs. Fielding had said, count blessings, look at silver linings. But Mrs. Fielding herself was so disturbed she couldn’t go on driving. She was forced to stop at a little café by the sea, and the two women had sat for a long time facing each other across a greasy, crumb-covered table. Mrs. Fielding kept right on talking, raising her voice against the crash of waves on pilings and the clatter of dishes from the kitchen.

Now, five years later, she was still using some of the same words. “Count your blessings, Daisy. You’re secure and comfortable, you’re in good health, surely you have the world’s nicest husband.”

“Yes,” Daisy said. “Yes.” She thought of the tombstone in her dream, and the date of her death, December 2, 1955. Four years ago, not five. And the trip to see the specialist must have taken place in the spring, not in December, because the hills had been green. There was no connection between the day of the trip and what Daisy now capitalized in her mind as The Day.

“Also,” Mrs. Fielding continued, “you should be hearing from one of the adoption agencies any day now—you’ve been on the list for some time. Perhaps you should have applied sooner than last year, but it’s too late to worry about that now. Look on the bright side. One of these days you’ll have a baby, and you’ll love it just as much as you would your own, and so will Jim. You don’t realize sometimes how lucky you are simply to have Jim. When I think of what some women have to put up with in their marriages…”

Meaning herself, Daisy thought.

“…you are a lucky, lucky girl, Daisy.”

“Yes.”

“I think the main trouble with you is that you haven’t enough to do. You’ve let so many of your activities slide lately. Why did you drop your course in Russian literature?”

“I couldn’t keep the names straight.”

“And the mosaic you were making…”

“I have no talent.”

As if to demonstrate that there was at least some talent around the house, Stella burst into song while she washed the breakfast dishes.

Mrs. Fielding went over and closed the kitchen door, not too subtly. “It’s time you started a new activity, one that will absorb you. Why don’t you come with me to the Drama Club luncheon this noon? Someday you might even want to try out for one of our plays.”

“I doubt that very—”

“There’s absolutely nothing to acting. You just do what the director tells you. They’re having a very interesting speaker at the luncheon. It would be a lot better for you to go out than to sit here brooding because you dreamed somebody killed you.”

Daisy leaned forward suddenly in her chair, pushed the dog’s paw off her lap, and got up. “What did you say?”

“Didn’t you hear me?”

“Say it again.”

“I see no reason to…” Mrs. Fielding paused, flushed with annoyance. “Well, all right. Anything to humor you. I simply stated that I thought it would be better for you to come with me to the luncheon than to sit here brooding because you had a bad dream.”

“I don’t think that’s quite accurate.”

“It’s as close as I can remember.”

“You said, ‘because I dreamed somebody killed me.’” There was a brief silence. “Didn’t you?”

“I may have.” Mrs. Fielding’s annoyance was turning into something deeper. “Why fuss about a little difference in words?”

Not a little difference, Daisy thought. An enormous one. “I died” had become “someone killed me.”

She began to pace up and down the room again, followed by the reproachful eyes of the dog and the disapproving eyes of her mother. Twenty-two steps up, twenty-two steps down. After a while the dog started walking with her, heeling, as if they were out for a stroll together.

We were walking along the beach below the cemetery, Prince and I, and suddenly Prince disappeared up the cliff. I could hear him howling. I whistled for him, but he didn’t come. I went up the path after him. He was sitting beside a tombstone. It had my name on it: Daisy FieldingHarker. Born November 13, 1930. Killed December 2, 1955…