Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

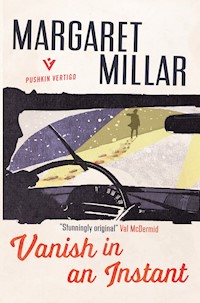

A rediscovered classic of American noir from one of crime writing's greatest talents "In the whole of crime fiction's distinguished sisterhood, there is no one quite like Margaret Millar"Guardian Virginia Barkeley is a nice, well brought-up girl. So what is she doing wandering through a snow storm in the middle of the night, blind drunk and covered in someone else's blood? When Claude Margolis' body is found a quarter of a mile away with half-a-dozen stab wounds to the neck, suddenly Virginia doesn't seem such a nice girl after all. Her only hope is Meecham, the cynical small-town lawyer hired as her defence. But how can he believe in Virginia's innocence when even she can't be sure what happened that night? And when the answer seems to fall into his lap, why won't he just walk away? "One of the most original and vital voices in all of American crime fiction"Laura Lippman, author of Sunburn Margaret Millar (1915-1994) was the author of 27 books and a masterful pioneer of psychological mysteries and thrillers. Born in Kitchener, Ontario, she spent most of her life in Santa Barbara, California, with her husband Ken Millar, who is better known by his nom de plume of Ross Macdonald. Her 1956 novel Beast in View won the Edgar Allan Poe Award for Best Novel. In 1965 Millar was the recipient of the Los Angeles Times Woman of the Year Award and in 1983 the Mystery Writers of America awarded her the Grand Master Award for Lifetime Achievement. Millar's cutting wit and superb plotting have left her an enduring legacy as one of the most important crime writers of both her own and subsequent generations.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 339

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

“She has few peers, and no superior in the art of bamboozlement”

JULIAN SYMONS, THE COLOUR OF MURDER

“Mrs Millar doesn’t attract fans, she creates addicts”

DILYS WINN

“She writes minor classics”

WASHINGTON POST

“Very original”

AGATHA CHRISTIE

“Margaret Millar was one of the pioneers of domestic suspense, a standout chronicler of inner psychology and the human mind. Vanish in an Instant is a perfect gateway to her fiction, after which you’ll devour so many more of her classic novels”

SARAH WEINMAN, AUTHOR OF THE REAL LOLITA AND EDITOR OF WOMEN CRIME WRITERS: EIGHT SUSPENSE NOVELS OF THE 1940S & 50S

“The real queen of suspense… Millar’s psychologically complex, disturbingly dark thrillers always manage to surprise the reader… She can’t write a dull sentence, and her endings always deliver a shock”

CHRISTOPHER FOWLER, AUTHOR OF THE BRYANT & MAY MYSTERIES

“Margaret Millar is ripe for rediscovery. Compelling characters, evocative settings, subtle and ingenious plots – what more could a crime fan wish for?”

MARTIN EDWARDS, AUTHOR OF THE LAKE DISTRICT MYSTERIES

“No woman in twentieth-century American mystery writing is more important than Margaret Millar”

DOROTHY B HUGHES, AUTHOR OF IN A LONELY PLACE

“Margaret Millar can build up the sensation of fear so strongly that at the end it literally hits you like a battering ram”

BBC

“Millar was the master of the surprise ending”

INDEPENDENT ON SUNDAY

For my loved ones

MILL AND LINDA

CONTENTS

ONE

Snow and soot sprinkled the concrete runways like salt and pepper. Twenty miles to the east Detroit was a city of smoke and lights. Twenty miles to the west the town of Arbana was not visible at all, but it was to the west that Mrs. Hamilton looked first as if she hoped to catch a miraculous glimpse of it.

On the observation ramp above the airfield she could see the faces of people waiting to board a plane or to meet someone or simply waiting and watching, because if they couldn’t go anywhere themselves, the next best thing was to watch someone else going. Under the glaring lights their faces appeared as similar as the rows of wax vegetables in the windows of the markets back home. She scanned the faces briefly, wondering if one of them belonged to her son-in-law, Paul. She wasn’t sure she would recognize him—in her mind he had never entirely taken shape as a person, he was just Virginia’s husband—or that he would recognize her.

“I certainly haven’t changed,” she said aloud, quite sharply.

Her companion turned with an air of surprise. She was a slim girl in her early twenties, rather pretty, though her fair hair and extremely light eyebrows gave her a frail and colorless appearance. Her eyes were deep blue and round, so that she always looked a little inquisitive, like a child to whom everything is new. “Did you say something, Mrs. Hamilton?”

“People don’t change very much in a year, unless it’s a bad year. And I haven’t really had a bad year until this—until now.”

The girl made a sympathetic sound, to which Mrs. Hamilton reacted stiffly. Mrs. Hamilton actively disliked and resented sympathy. In contrast to her plump small-boned body, her nature was brisk and vigorous. Holding her large black purse firmly under her arm she crossed the swept concrete apron toward the entrance to the terminal. As she passed the ramp she glanced up at the vegetable-faces once more.

“I don’t see Paul. Do you, Alice?”

“He might be waiting inside,” the girl said. “It’s cold.”

“I told you to be sure and buy a warm enough coat.”

“The coat’s warm enough. But the wind isn’t.”

“Californians get spoiled. For winter this is quite balmy.” But her own lips were blue-tinged, and her fingers inside the white doeskin gloves felt stiff as though they were in splints. “I didn’t ask him to meet me in my telegram. Well, we’ll take a taxi to Arbana. What time is it?”

“About nine.”

“Too late. They probably won’t let me see Virginia tonight.”

“Probably not.”

“I guess the—I guess they have visiting hours like a hospital.” She spoke the word they as if it had an explosive content and must be handled carefully.

There was a line-up at the luggage counter, and they took their places at the end of it. To Mrs. Hamilton, who was quick to sense atmosphere, the big room had an air of excitement gone stale, anticipation soured by reality.

Journey’s end, she thought. She felt stale and sour herself, and the feeling reminded her of Virginia; Virginia at Christmas time, the year she was eight. For weeks and weeks the child had dreamed of Christmas, and then on Christmas morning she had awakened and found that Christmas was only another day. There were presents, of course, but they weren’t, they never could be, as big and exciting and mysterious as the packages they came in. In the afternoon Virginia had wept, rocking herself back and forth in misery.

“I want my Christmas back again. I want my Christmas!” Mrs. Hamilton knew now that what Virginia had wanted back were the wild and wonderful hopes, the boxes unopened, the ribbons still in bows.

Soon, in two weeks, there would be a new Christmas. She wondered, grimly, if Virginia would weep for its return when it was gone.

“You must be tired,” Alice said. “Why don’t you sit down and let me wait in line?”

The response was crisp and immediate. “No, thanks. I refuse to be treated like an old lady, at my age.”

“Willett told me I was to be sure and look after you properly.”

“My son Willett was born to be an old maid. I have no illusions about my children. Never had any. I know that Virginia is temperamental. But that’s all. There’s no harm in her.” She rubbed her moist pallid forehead with a handkerchief. The room seemed unbearably hot, suddenly, and she was unbearably tired, but she felt impelled to go on talking. “The charge is false, preposterous. In a small town like Arbana the police are inefficient and probably corrupt. They’ve made an absurd mistake.”

She had spoken the same words a dozen times in the past dozen hours. They had, with repetition, gained force and speed like a runaway car going downhill, heading for a crash.

“Wait until you meet her, Alice. You’ll find out for yourself.”

“I’m sure I will.” Yet the more Mrs. Hamilton talked about Virginia, the more obscure Virginia became, hidden in a thicket of words like an unknown animal.

“I have no illusions,” the older woman repeated. “She is temperamental, even bad-tempered at times, but she’s incapable of injuring anyone deliberately.”

Alice murmured an indistinct but reassuring answer. She had become conscious, suddenly, of being a focus of attention. She turned and looked over Mrs. Hamilton’s shoulder toward the exit door. A man was standing near the door watching her. He was in his middle thirties, tall, a little slouched as if he worked too long at a desk, and a little hard-faced, as if he didn’t enjoy it. He wore a tweed topcoat that looked new, and a gray fedora and heavy brown English brogues.

“I think your son-in-law just came in.”

Mrs. Hamilton turned too, and glanced brightly at the man. “That’s not Paul. Too well-dressed. Paul always looks like someone in a soup line.”

“He seems to know you, by the way he stares.”

“Nonsense. Don’t be so modest. He’s staring at you. You’re a pretty girl.”

“I don’t feel pretty.”

“No woman feels pretty without a man. I used to feel pretty, though I never was, of course.”

It was true. She had never been pretty even as a girl. Her head was too large for her body and emphasized by thick brown hair that was now burning itself out like a grass-fire and showing streaks of ashes. “You must learn to pretend, Alice. After all, you’re not a schoolteacher any more. You’re a young woman of the world, you’re traveling, all sorts of exciting things can happen to you. Don’t you feel that?”

“No,” Alice said simply.

“Well, try.”

The man at the door had come to a decision. He crossed the room briskly, removing his hat as he walked.

“Mrs. Hamilton?”

Mrs. Hamilton faced him, a slight frown creasing the skin between her eyebrows. The encounter, whatever it meant, wasn’t in her plans. She had no time to waste or energy to squander on a stranger. She gripped her purse a little tighter as if the stranger had come to steal something from her.

“Yes, I’m Mrs. Hamilton.”

“My name is Eric Meecham. Dr. Barkeley sent me to meet you.”

“Oh. Well, how do you do?”

“How do you do?” He had a low-pitched voice with a faint rumble of impatience in it.

“You’re a friend of Paul’s?”

“No.”

“Then?”

“I’m a lawyer. I’ve been retained to represent your daughter.”

“Who hired you?”

“Dr. Barkeley.”

“In my wire I instructed him to wait until I arrived.”

Meecham returned her frown. “Well, he didn’t. He wanted me to try and get her out of jail right away.”

“And did you?”

“No.”

“Why not? If it’s money, I have…”

“It’s not money. They can hold her for forty-eight hours without charge. It looks as if that’s what they’re going to do.”

“But how can they hold an innocent girl?”

Meecham picked up the question carefully as if it was loaded. “The fact is, she hasn’t claimed to be innocent.”

“What—what does she claim?”

“Nothing. She won’t deny anything, won’t admit anything, won’t, period. She’s…” He groped for a word and out of the number that occurred to him he chose the least offensive: “She’s a little difficult.”

“She’s frightened, the poor child. When she’s frightened she’s always difficult.”

“I can see that.” The line-up had dwindled down to just the three of them. Meecham looked questioningly at Alice, then turned back to Mrs. Hamilton. “You came alone?”

“No. No, I’m sorry, I forgot to introduce you. Alice, this is Mr. Meecham. Miss Dwyer.”

Meecham nodded. “How do you do?”

“Alice is a friend of mine,” Mrs. Hamilton explained.

“I’m a hired companion, really,” Alice said.

“Really? If you’ll give me the luggage checks, I’ll get your things and take them out to my car.”

Mrs. Hamilton handed him the checks. “It was kind of you to go to all this trouble.”

“No trouble at all.” The words were polite but without conviction.

He carried the four suitcases out to the car and piled them in the luggage compartment. The car was new but splattered with mud and there was a dent in the left rear fender.

The two women sat in the back and Meecham alone in the front. No one spoke for the first few miles. Traffic on the highway was heavy and the pavement slippery with slush.

Alice looked out at the countryside visible in the glare of headlights. It was bleak and flat, covered with patches of gray snow. A wave of homesickness swept over her, and mingled with it was a feeling much stronger and more violent than homesickness. She hated this place, and she hated the lawyer because he belonged to it. He was as crude and stark as the landscape and as ungracious as the weather.

Mrs. Hamilton seemed to share her feeling. She reached over suddenly and patted Alice’s hand. Then she straightened up and addressed Meecham in her clear, deliberate voice: “Just what are your qualifications for this work, Mr. Meecham?”

“I took my law degree here at the University and played office boy to the firm of Post and Cranston until they found me indispensable and put my name on a door. Is that what you want to know?”

“I want to know what experience you’ve had with criminal cases.”

“I’ve never handled a murder case, if that’s what you mean,” he said frankly. “They’re not common around town. You know Arbana?”

“I’ve been there. Once.”

“Then you know it’s a university town and it hasn’t a crime rate like Detroit’s. The biggest policing problem is the traffic after football games. Naturally there’s a certain percentage of auto thefts, robberies, morals offenses and things like that. But there hasn’t been a murder for two years, until now.”

“And they’ve arrested my daughter.”

“Yes.”

“I can’t, I just can’t believe it. All they had to do is take one look at Virginia to realize that she’s a—a nice girl, well brought up.”

“Nice girls have been in trouble before.”

There was a brief silence. “You sound as if you think she’s guilty.”

“I’ve formed no opinion.”

“You have. I can tell.” Mrs. Hamilton leaned forward, one hand on the back of Meecham’s seat. “Excuse me if I sound rude,” she said softly, “but I’m not sure you’re qualified to handle this business.”

“I’m not sure either, but I’m going to try.”

“Naturally you’ll try. If murders are as rare in this town as you claim, it would be quite a feather in your cap to conduct a defense, wouldn’t it?”

“It could be.”

“I don’t believe I’d like to see you wearing that feather, at my daughter’s expense.”

“What do you suggest that I do, Mrs. Hamilton?”

“Retire gracefully.”

“I’m not graceful,” Meecham said.

“I see. Well, I’ll talk it over with Paul tonight.”

They were approaching the town. There was a red neon glow in the sky and service stations and hamburger stands appeared at shorter intervals along the highway.

Mrs. Hamilton spoke again. “It’s not that I have anything against you personally, Mr. Meecham.”

“No.”

“It’s just that my daughter is the most important thing in my life. I can’t take any chances.”

Meecham thought of a dozen retorts, but he didn’t make any of them. He felt genuinely sorry for the woman, or for anyone to whom Virginia Barkeley was the most important thing in life.

TWO

One wing of the house was dark, but in the other wing lights streamed from every window like golden ribbons.

The place was larger than Meecham had expected, and its flat roof and enormous windows looked incongruous in a winter setting. It was a Southern California house, of redwood and fieldstone. Meecham wondered whether Virginia had planned it that way herself, deliberately, because it reminded her of home, or unconsciously, as a symbol of her own refusal to conform to a new environment.

The driveway entrance to the house was through a patio that separated the two wings. Here, too, the lights were on, revealing hanging baskets of dead plants and flowerpots heaped with snow, and a barbecue pit fringed with tiny icicles.

Mrs. Hamilton’s eyes were squinted up as if she was going to cry at the sight of Virginia’s patio, built for sun and summer and now desolate in the winter night. Silently she got out of the car and moved toward the house.

Meecham pushed back his hat in a gesture of relief. “Quite a character, eh?”

“I like her. She’s very pleasant to me.”

“Oh?” He stood aside while Alice stepped out of the car. “You’re a little young to be a hired companion. How long have you worked for her?”

“About a month.”

“Why?”

“Why? Well…” She flushed again. “Well, that’s a silly question. I have to earn a living.”

“I meant, it’s a funny kind of job for a young girl.”

“I used to be a schoolteacher. Only I wasn’t meeting…” any eligible men were the words that occurred to her, but she said instead, “I was getting into a rut, so I decided to change jobs for a year or so.”

He gave her a queer look and went around to the back of the car to unlock the luggage compartment. Mrs. Hamilton had gone into the house, leaving the front door open.

Meecham put the four suitcases on the shoveled drive and relocked the compartment. “I suppose you know what you’re getting into.”

“I—of course. Naturally.”

“Naturally.” He looked slightly amused. “I gather you haven’t met Virginia.”

“No. I’ve heard a lot about her, though, from her brother, Willett, and from Mrs. Hamilton. She seems to be—well, rather an unhappy person.”

“You have to be pretty unhappy,” Meecham said, “to stab a guy half a dozen times in the neck. Or didn’t you know about that?”

“I knew it.” She meant to sound very positive, like Mrs. Hamilton, but her voice was squeezed into a tight little whisper. “Of course I knew it.”

“Naturally.”

“You’re quite objectionable.”

“I am when people object to me,” Meecham said. “I’ve forgotten your name, by the way, what is it?”

Instead of answering she picked up two of the suitcases and went ahead into the house.

Mrs. Hamilton heard her coming and called out, “Alice? I’m here, in the living room. Bring Mr. Meecham in with you. Perhaps he’d like some coffee.”

Alice looked coldly at Meecham who had followed her in. “Would you like some coffee?”

“No, thanks, Alice.”

“I don’t permit total strangers to call me Alice.”

“Okay, kid.” He looked as if he was going to laugh, but he didn’t. Instead, he said, “We seem to have started off on the wrong foot.”

“Since we’re not going anywhere together, what does it matter?”

“Have it your way.” He put on his hat. “Tell Mrs. Hamilton I’ll meet her tomorrow morning at 9:30 at the county jail. She can see Virginia then.”

“Couldn’t she phone her tonight or something?”

“The girl’s in jail. She’s not staying at the Waldorf.” He said over his shoulder as he went out the door, “Good night, kid.”

“Alice?” Mrs. Hamilton repeated. “Oh, there you are. Where’s Mr. Meecham?”

“He left.”

“Perhaps I was a little harsh with him, challenging his abilities.” She was standing in front of the fireplace, still in her hat and coat, and rubbing her hands together as if to get warm, though the fire wasn’t lit. “I’m afraid I antagonized him. I couldn’t help it. I felt he had the wrong attitude toward Virginia.”

The room was very large and colorful, furnished in rattan and bamboo and glass like a tropical lanai. There were growing plants everywhere, philodendron and ivy hanging from copper planters on the walls, azaleas in tubs, and cyclamen and coleus and saintpaulia in bright coralstone pots on the mantel and on every shelf and table. The air was humid and smelled of moist earth like a field after a spring rain.

The whole effect of the room was one of impossible beauty and excess, as if the person who lived there lived in a dream.

“She loves flowers,” Mrs. Hamilton said. “She isn’t like Willett, my son. He’s never cared for anything except money. But Virginia is quite different. Even when she was a child she was always very gentle with flowers as she was with birds and animals. Very gentle and understanding…”

“Mrs. Hamilton.”

“…as if they were people and could feel.”

“Mrs. Hamilton,” Alice repeated, and the woman blinked as if just waking up. “Why is Virginia in jail? What did she do?”

She was fully awake now, the questions had struck her vulnerable body as hailstones strike a field of sun-warmed wheat. “Virginia didn’t do anything. She was arrested by mistake.”

“But why?”

“I’ve told you, Paul’s wire to me was very brief. I know none of the details.”

“You could have asked Mr. Meecham.”

“I prefer to get the details from someone closer to me and to Virginia.”

She doesn’t want the facts at all, Alice thought. All she wants is to have Virginia back again, the gentle child who loved animals and flowers.

A middle-aged woman in horn-rimmed glasses and a white uniform came into the room carrying a cup of coffee, half of which had spilled into the saucer. She had a limp but she moved very quickly as if she thought speed would cover it. She had a spot of color on each cheekbone, round as coins.

“Here you are. This’ll warm you up.” She spoke a little too loudly, covering her embarrassment with volume as she covered her limp with speed.

Mrs. Hamilton nodded her thanks. “Carney, this is Alice Dwyer. Alice, Mrs. Carnova.”

The woman shook Alice’s hand vigorously. “Call me Carney. Everyone does.”

“Carney,” Mrs. Hamilton explained, “is Paul’s office nurse, and an old friend of mine.”

“He phoned from the hospital a few minutes ago. He’s on his way.”

“We are old friends, aren’t we, Carney?”

The coins on the woman’s cheekbones expanded. “Sure. You bet we are.”

“Then what are you acting so nervous about?”

“Nervous? Well, everybody gets nervous once in a while, don’t they? I’ve had a busy day and I stayed after hours to welcome you, see that you got settled, and so forth. I’m tired, is all.”

“Is it?”

The two women had forgotten Alice. Carney was looking down at the floor, and the color had radiated all over her face to the tops of her large pale ears. “Why did you come? You can’t do anything.”

“I can. I’m going to.”

“You don’t know how things are.”

“Then tell me.”

“This is bad, the worst yet. I knew she was seeing Margolis. I warned her. I said I’d write and tell you and you’d come and make it hot for her.”

“You didn’t tell me.”

Carney spread her hands. “How could I? She’s twenty-six; that’s too old to be kept in line by threats of telling mama.”

“Did Paul know about this—this man?”

“I’m not sure. Maybe he did. He never said anything.” She plucked a dried leaf from the yam plant that was growing down from the mantel. “Virginia won’t listen to me any more. She doesn’t like me.”

“That’s silly. She’s always been devoted to you.”

“Not any more. Last week she called me a snooping old beer-hound. She said that when I applied for this job it wasn’t because Carnova had left me stranded in Detroit, it was because you sent me here to spy on her.”

“That’s ridiculous,” Mrs. Hamilton said crisply. “I’ll talk to Virginia tomorrow and see that she apologizes.”

“Apologizes. What do you think this is, some little game or something? Oh, God.” Carney exploded. She covered her face with her hands, half-laughing, half-crying and then she began to hiccough, loud and fast. “Oh—damn—oh—damn.”

Mrs. Hamilton turned to Alice. “We all need some rest. Come and I’ll show you your room.”

“I’ll—show—her.”

“All right. You go with Carney, Alice. I’ll wait up to say hello to Paul.”

Alice looked embarrassed. “I hated to stand there listening like that. About Virginia, I mean.”

“That’s all right, you couldn’t help it.” A car came up the driveway and stopped with a shriek of brakes. “Here’s Paul now. I’ll talk to him alone, Carney, if you don’t mind.”

“Why—should—I—mind?”

“And for heaven’s sake breathe into a paper bag or something. Good night.”

When they had gone Mrs. Hamilton stood in the center of the room for a moment, her fingertips pressing her temples, her eyes closed. She felt exhausted, not from the sleepless night she had spent, or from the plane trip, but from the strain of uncertainty, and the more terrible strain of pretending that everything would be all right, that a mistake had been made which could be rather easily corrected.

She went to open the door for Paul.

He came in, stamping the snow from his boots, a stocky, powerfully built man in a wrinkled trench coat and a damp shapeless gray hat. He looked like a red-cheeked farmer coming in from his evening’s chores, carrying a medical bag instead of a lantern.

He had a folded newspaper under his arm. Mrs. Hamilton glanced at the newspaper and away again.

“Well, Paul.” They shook hands briefly.

“I’m glad you got here all right.” He had a very deep warm voice and he talked rather slowly, weighing out each word with care like a prescription. “Sorry I couldn’t meet you—Mother.”

“You don’t have to call me Mother, you know, if it makes you uncomfortable.”

“Then I won’t.” He laid his hat and trench coat across a chair and put his medical bag on top of them. But he kept the newspaper in his hand, rolling it up very tight as if he intended to use it as a weapon, to swat a fly or discipline an unruly pup.

Mrs. Hamilton sat down suddenly and heavily, as though the newspaper had been used against her. The light from the rattan lamp struck her face with the sharpness of a slap. “That paper you have, what is it?”

“One of the Detroit tabloids.”

“Is it…?”

“It’s all in here, yes. Not on the front page.”

“Are there any pictures?”

“Yes.”

“Of Virginia?”

“One.”

“Let me see.”

“It’s not very pretty,” he said. “Perhaps you’d better not.”

“I must see it.”

“All right.”

The pictures occupied the entire second page. There were three of them. One, captioned DEATH SHACK, showed a small cottage, its roof heavy with fresh snow and its windows opaque with frost. The second was of a sleek dark-haired man smiling into the camera. He was identified as Claude Ross Margolis, forty-two, prominent contractor, victim of fatal stabbing.

The third picture was of Virginia, though no one would have recognized her. She was sitting on some kind of bench, hunched over, with her hands covering her face and a tangled mass of black hair falling over her wrists. She wore evening slippers, one of them minus a heel, and a long fluffy dress and light-colored coat. The coat and dress and one of the shoes showed dark stains that looked like mud. Above the picture were the words, held for questioning, and underneath it Virginia was identified as Mrs. Paul Barkeley, twenty-six, wife of Arbana physician, allegedly implicated in the death of Claude Margolis.

Mrs. Hamilton spoke finally in a thin, ragged whisper: “I’ve seen a thousand such dreary pictures in my life, but I never thought that some day one of them would be terribly different to me from all the others.”

She looked up at Barkeley. His face hadn’t changed expression, it showed no sign of awareness that the girl in the picture was his wife. A little pulse of resentment began to beat in the back of Mrs. Hamilton’s mind: He doesn’t care—he should have taken better care of Virginia—this would never have happened. Why wasn’t he with her? Or why didn’t he keep her at home?

She said, not trying to hide her resentment, “Where were you when it happened, Paul?”

“Right here at home. In bed.”

“You knew she was out.”

“She’d been going out a great deal lately.”

“Didn’t you care?”

“Of course I cared. Unfortunately, I have to make a living. I can’t afford to follow Virginia around picking up the pieces.” He went over to the built-in bar in the south corner of the room. “Have a nightcap with me.”

“No, thanks. I—those stains on her clothes, they’re blood?”

“Yes.”

“Whose blood?”

“His. Margolis’.”

“How can they tell?”

“There are lab tests to determine whether blood is human and what type it is.”

“Well. Well, anyway, I’m glad it’s not hers.” She hesitated, glancing at the paper and away again, as if she would have liked to read the report for herself but was afraid to. “She wasn’t hurt?”

“No. She was drunk.”

“Drunk?”

“Yes.” He poured some bourbon into a glass and added water. Then he held the glass up to the light as if he was searching for microbes in a test tube. “A police patrol car picked her up. They found her wandering around about a quarter of a mile from Margolis’ cottage. It was snowing very hard; she must have lost her way.”

“Wandering around in the snow with only that light coat and those thin shoes—oh God, I can’t bear it.”

“You’ll have to,” he said quietly. “Virginia’s depending on you.”

“I know, I know she is. Tell me—the rest.”

“There isn’t much. Margolis’ body had been discovered by that time because something had gone wrong with the fireplace in the cottage. There was a lot of smoke, someone reported it, and the highway patrol found Margolis inside dead, stabbed with his own knife. He’d been living in the cottage which is just outside the city limits because his own house was closed. His wife is in Peru on a holiday.”

“His wife. He was married.”

“Yes.”

“There were—children?”

“Two.”

“Drunk,” Mrs. Hamilton whispered. “And out with a married man. There must be some mistake, surely, surely there is.”

“No. I saw her myself. The Sheriff called me about three o’clock this morning and told me she was being held and why. I wired you immediately, and then I went down to the county jail where they’d taken her. She was still drunk, didn’t even recognize me. Or pretended not to. How can you tell, with Virginia, what’s real and what isn’t?”

“I can tell.”

“Can you?” He sipped at his drink. “The sheriff and a couple of deputies were there trying to get a statement from her. They didn’t get one, of course. I told them it was silly to go on questioning anyone in her condition, so they let her go back to bed.”

“In a cell? With thieves and prostitutes and…”

“She was alone. The cell—room, rather, was clean. I saw it. And the matron, or deputy, I think they called her, seemed a decent young woman. The surroundings aren’t quite what Virginia is used to, but she’s not suffering. Don’t worry about that part of it.”

“You don’t appear to be worrying at all.”

“I’ve done nothing but worry, for a long time.” He hesitated, looking at her across the room as if wondering how much of the truth she wanted to hear. “You may as well know now—Virginia will tell you, if I don’t—that this first year of our marriage has been bad. The worst year of my life, and maybe the worst in Virginia’s too.”

Mrs. Hamilton’s face looked crushed, like paper in a fist. “Why didn’t someone tell me? Virginia wrote to me, Carney wrote. No one said anything. I thought things were going well, that Virginia had settled down with you and was happy, that she was finally happy. Now I find out I’ve been deceived. She didn’t settle down. She’s been running around with married men, getting drunk, behaving like a cheap tart. And now this, this final disgrace. I just don’t know what to do, what to think.”

He saw the question in her eyes, and turned away, holding his glass up to the light again.

“I did what I could, hired a lawyer.”

“Yes, but what kind? A man with no experience.”

“He was recommended to me.”

“He’s not good enough. Virginia should have the best.”

“She should indeed,” he said dryly. “Unfortunately, I can’t afford the best.”

“I can. Money is no object.”

“That money-is-no-object idea is a little old-fashioned, I’m afraid.” He put down his empty glass. “There’s another point. If Virginia is innocent, she won’t need the best. Now if you’ll excuse me, I think I’ll go to bed. I have to keep early hours. Carney showed you your room, I suppose?”

“Yes.”

“Make yourself at home as much as possible. The house is yours,” he added with a wry little smile. “Mortgage and all. Good night, Mrs. Hamilton.”

“Good night.” She hesitated for a split second before adding, “my boy.”

He went out of the room. She followed him with her eyes; they were perfectly dry now, and hard and gray as granite.

Red-faced farmer, she thought viciously.

THREE

In the summer the red bricks of the courthouse were covered with dirty ivy and in the winter with dirty snow. The building had been constructed on a large square in what was originally the center of town. But the town had moved westward, abandoned the courthouse like an ugly stepchild, leaving it in the east end to fend for itself among the furniture warehouses and service stations and beer-and-sandwich cafés.

Across the road from the main entrance was a supermarket. Meecham parked his car in front of it. Its doors were still closed, though there was activity inside. Along the aisles clerks moved apathetically, slowed by sleep and the depression of a winter morning that was no different from night. Street lamps were still burning, the sky was dark, the air heavy and damp.

Meecham crossed the road. He felt sluggish, and wished he could have stayed in bed until it was light.

In front of the courthouse a thirty-foot Christmas tree had been put up and four county prisoners were stringing it with colored lights under the direction of a deputy. The deputy wore fuzzy orange ear-muffs, and he kept stamping his feet rhythmically, either to keep warm or because there was nothing else to do.

When Meecham approached, all four of the prisoners stopped work to look at him, as they stopped to look at nearly everyone who passed, realizing that they had plenty of time and nothing to lose by a delay.

“Speed it up a little, eh, fellows?” The deputy whacked his hands together. “What’s the matter, you paralyzed or something, Joe?”

Joe looked down from the top of the ladder and laughed, showing his upper teeth filled at the gum-line with gold. “How’d you like to be inside with a nice rum toddy, Huggins? Mmm?”

“I never touch the stuff,” Huggins said. “Morning, Meecham.”

Meecham nodded. “Morning.”

“Up early catching worms?”

“That’s right.”

Huggins jerked his thumb at the ladder. “Me, I’m trying to inject the spirit of Christmas into these bums.”

Three of the men laughed. The fourth spat into the snow.

Meecham went inside. The steam had been turned on full force and the old-fashioned radiators were clanking like ghosts rattling their chains. Meecham was sweating before he reached the middle of the corridor, and the passages from his nose to his throat felt hot and dry as if he’d been breathing fire.

The main corridor smelled of wood and fresh wax, but when he descended the stairs on the left a new smell rose to overpower the others, the smell of disinfectant.

The door lettered County Sheriff was open. Meecham walked into the anteroom and sat down in one of the straight chairs that were lined up against the wall like mute and motionless prisoners. The anteroom was empty, though a man’s coat and hat were hanging on a rack in the corner, and the final inch of a cigarette was smoldering in an ash tray on the scarred wooden counter. Meecham looked at the cigarette but made no move to put it out.

The door of the Sheriff’s private office banged open suddenly and Cordwink himself came out. He was a tall man, match-thin, with gray hair that was clipped short to disguise its curl. His eyelashes curled too, giving his cold eyes a false appearance of naivete. He had fifty years of hard living behind him, but they didn’t show except when he was tired or when he’d had a quarrel with his wife over money or one of the kids.

“What are you doing around so early?” Cordwink said.

“I wanted to be the first to wish you a Merry Christmas.”

“You bright young lawyers, you keep me all the time in stitches. Yah.” He scowled at the cigarette smoldering in the ash tray. “What the hell you trying to do, burn the place down?”

“It’s not my…”

“That’s about the only way you’ll get your client out of here.”

“Oh?” Meecham lit a cigarette and used the burnt match to crush out the burning remnants of tobacco in the ash tray. “Have you dug up any new information?”

“I should tell you?” Cordwink laughed. “You bloody lawyers can do your own sleuthing.”

“Kind of sour this morning, aren’t you, Sheriff?”

“I’m in a sour business, I meet sour people, so I’m sour. So?”

“So you didn’t get a statement from Mrs. Barkeley.”

“Sure I got a statement.”

“Such as?”

“Such as that I’m an illiterate buffoon of canine parentage.”

Meecham grinned.

“That strikes you as humorous, eh, Meecham?”

“Moderately.”

“Well, it so happens that I graduated from the University of Wisconsin, class of ’22.”

“Funny, I thought you were a Harvard man. You act and talk like a…”

“You bright young lawyers kill me.” He grunted. “Yah. Well, I don’t care if she makes a statement or not. We have her.”

“Maybe.”

“Even you ought to be smart enough to see that. You’d better start combing the books for some fancy self-defense items. Make sure you get a nice stupid jury, then razz the cops, turn on the tears, quote the Bible—yah! Makes me sick. What a way to make a living, obstructing justice.”

“I’ve heard the theme song before, Sheriff. Let’s skip the second chorus.”

“You think I’m off-key, eh?”

“Sure you are.”

Cordwink pressed a buzzer on the counter. “You won’t get away with a self-defense plea. There isn’t a mark on the girl, no cut, no bruise, not a scratch.”

“I don’t have to prove that the danger to her person was objectively real and imminent, only that she thought, and had reason to think, that it was real and imminent.”

“You’re not in court yet, so can the jargon. Makes me sick.”

The Sheriff pressed the buzzer again and a moment later a young woman in a green dress came into the room blithely swinging a ring of keys.

She greeted Meecham with a show of fine white teeth. “You again, Mr. Meecham.”

“Right.”

“You ought to just move in.” She switched the smile on Cordwink. “Isn’t that right, Sheriff?”

“Righter than you think,” Cordwink said. “If justice was done, the place would be crawling with lawyers.” He started toward his office. “Show the gentleman into Mrs. Barkeley’s boudoir, Miss Jennings.”

“Okeydoke.” Cordwink slammed his door and Miss Jennings added, in a stage whisper, “My, aren’t we short-tempered this morning.”

“Must be the weather.”

“You know, I think it is, Mr. Meecham. Personally, the weather never bothers me. I rise above it. When winter comes can spring be far behind?”

“You have something there.”

“Shakespeare. I adore poetry.”

“Good, good.” He followed her down the corridor. “How is Mrs. Barkeley?”

“She had a good sleep and a big breakfast. I think she’s finally over her hangover. My, it was a beaut.” She unlocked the door at the end of the corridor and held it open for Meecham to go through first. “She borrowed my lipstick. That’s a good sign.”

“Maybe. But I don’t know of what.”

“Oh, you’re just cynical. So many people are cynical. My mother often says to me, Mollie dear, you were born smiling and you’ll probably go out smiling.”

Meecham shuddered. “Lucky girl.”

“Yes, I am lucky. I simply can’t help looking at the cheerful side.”

“Good for you.”

The women’s section of the cell-block was empty except for Virginia. Miss Jennings unlocked the door. “Here’s that man again, Mrs. Barkeley.”

Virginia was sitting on her narrow cot reading, or pretending to read, a magazine. She was wearing the yellow wool dress and brown sandals that Meecham had brought to her the previous afternoon, and her black hair was brushed carefully back from her high forehead. She had used Miss Jennings’ lipstick to advantage, painting her mouth fuller and wider than it actually was. In the light of the single overhead bulb her flesh looked smooth and cold as marble. Meecham found it impossible to imagine what emotions she was feeling, or what was going on behind her remote and beautiful eyes.

She raised her head and gave him a long unfriendly stare that reminded him of Mrs. Hamilton, though there was no physical resemblance between the mother and daughter.

“Good morning, Mrs. Barkeley.”

“Why don’t you get me out of here?” she said flatly.

“I’m trying.”

He stepped inside and Miss Jennings closed the door behind him but didn’t lock it. She retired to the end of the room and sat down on a bench near the exit door. She hummed a few bars of music, very casually, to indicate to Meecham and Virginia that she had no intention of eavesdropping.