Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

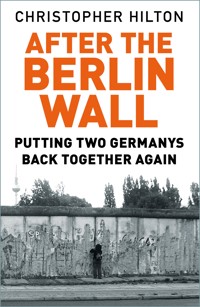

On 7 May 1945, Grand Admiral Donitz, named in Hitler's will as head of state, authorised the unconditional surrender of all German forces to the Allies on the following day. World War II in Europe was at an end. But many of the German people would continue to endure hardships, as both the country and the capital were to be divided between France, the UK and the USA in the west and the USSR in the east. East and West Germany, and East and West Berlin, would remain divided until 1989. By October 1990, however, the two countries were reunited, and the Berlin Reichstag was once again the seat of government. Here, politicians would put East and West back together again, marrying a totalitarian, atheist, communist system with a democratic, Christian, capitalist one. How did this marriage affect the everyday life of ordinary Germans? How did combining two telephone systems, two postal services, hospitals, farm land, property, industry, railways and roads work? How were women's rights, welfare, pensions, trades unions, arts, rents and housing affected? There had been no warning of this marriage and no preparation for it - and no country had ever tried putting two completely opposite systems together before. This is the story of what happened, in the words of the people it happened to - the people's story of an incredible unification.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 462

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

AFTER THE

BERLIN WALL

AFTER THE

BERLIN WALL

PUTTING TWO GERMANYS BACK TOGETHER AGAIN

CHRISTOPHER HILTON

First published 2009

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

© Christopher Hilton, 2009, 2011

The right of Christopher Hilton, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7996 5

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7995 8

Original typesetting by The History Press

Can Germans still claim a common identity after forty years of partition or are there now two different ways of thinking and living?

Peter Daniel, The German Comedy, 1991

Carlo says he does not regard himself as East or West; he has no prejudice. Is that the future?

Yes. European. I believe his is the generation which will just grow up thinking of themselves as Germans or Europeans. Even among the three children there is a difference. For instance, the little one – Elisa – goes to a school where the children learn Spanish and part of the lessons are in Spanish. For Elisa, Honecker, the GDR and The Wall have no meaning but Hitler somehow does. He is always there. He is in the newspapers every day.

Heike Herrmann, interview, 2008

CONTENTS

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Author’s Note

Timeline

1. History Lessons from The Wall Man

2. God, a Little Distance and the First Onion

3. Windows on the World

4. Reclaiming 1933, and 1945, and 1989

5. Taking your Medicine

6. The Other History Lessons

7. As If There Wasn’t a Border

8. Boot on the Other Foot

9. The Process of Approaching One Another

10. The Word in Stone

Afterword

Bibliography

FOREWORD

The first part of Adolf Hitler’s war ended with a single shot one April afternoon in 1945.

In the concrete Berlin catacomb he had had built so deep underground that he’d be safe from everyone – except, as it turned out, himself – he fired the shot into his temple while he bit on a vial of poison. The Third Reich he created to last 1,000 years limped on for another seven days, morally bankrupt and directionless, but the real end came with the shot.

In the aftermath, Germany would be divided and Germans forced to live in different countries, East and West, with a wall and shoot-to-kill guards between them. The catacomb was dynamited years later and, by chance, The Wall ran directly across the ground above it, then looped round the Brandenburg Gate – symbol of the city and now symbol of its division – a short walk away.

The second part of Adolf Hitler’s war ended with an explosion of champagne corks one November night in 1989 and people dancing on that loop of The Wall at the Brandenburg Gate.

The German Democratic Republic (GDR), a self-proclaimed sovereign state whose leader, Erich Honecker, had insisted The Wall would last for a hundred years,1 could not withstand this dance of death. It limped on for another five months, morally bankrupt and directionless, but the real end came with the champagne corks.

After that, Easterners had a real election and used it to vote themselves out of existence. As far as I am aware, no other country except Austria in 1938 has ever done this, and whether Austria – under extreme Nazi pressure to join the German Reich – actually did remains problematical. The Nazis gave them an ‘election’ and 99.73 per cent of the population said yes, a highly suspicious total made even more suspicious because of its familiarity to so many totalitarian regimes.2

From the outside, the GDR had a look of immovability and permanence, every aspect of life tightly controlled by the ruling Party and monitored by the security service, a monstrous, malign octopus. Strategically it was a key Soviet ally, the guarantee that these Germans at least would never again attack the Russian Motherland and were consequently locked into the Communist trading bloc (COMECON) and military alliance (the Warsaw pact). The Soviet Union had 350,000 troops stationed there.

Four weeks after Honecker said what he said, The Wall had gone and with it the GDR, gone without a shot fired or even a sprained ankle. The decision to open The Wall was announced by Günter Schabowski, a member of the Politbüro with responsibilities for East Berlin, at a press conference in the early evening of 9 November 1989. He was speaking in answer to a question (initiated by an Italian journalist) and had been given papers covering new orders but not actually read them. He read them now and they said the border was to open. He was asked when; he consulted the papers and said ‘immediately, without delay’. This was a defining moment for millions of people all over the Germanys, even though Schabowski’s replies were reticent because he hadn’t read the papers, creating a sense of ambiguity. His jowled face and sonorous voice became a defining image, too.

In this book many people will refer to it quite naturally as something central to their memories and their lives.

The third part of Adolf Hitler’s war began one October day in 1990 when East and West reunited, although everybody knew the truth. The FRG – with three times the population and the third largest economy on earth – was about to ingest the GDR whole, a python and a piglet.3 Wolfgang Schäuble, the FRG’s chief negotiator, wrote:

In my talk to them I kept saying: Dear folks, this is about the GDR’s affiliation with the Federal Republic, not the other way around … This is not the unification of two identical states. We do not start from the very beginning with equal starting positions. There is the Basic Law and there is the Federal Republic of Germany. Let us proceed on the assumption that you have been excluded from both for forty years.4

This new Germany would be run from the Reichstag, a very short walk from the Brandenburg Gate, as politicians put East and West back together for the first time since 1945. That involved marrying totalitarian communism with democratic capitalism, both of which had been constructed with characteristic German thoroughness, heightening every difference between the two.

Nobody had ever done this, either.

The takeover touched everything in the East: government, law, the judiciary, the police, whatever the East German government owned, including all the farmland, property and industry. It involved teachers and education, the whole medical profession and hospitals, crèches and kindergartens, foreign policy and the military, because one week two armies had been prepared to kill each other, the next they were in the same army. It involved bringing together two phone systems and the two postal services, two railways, all the roads and different speed limits. It involved women’s rights, abortion, every aspect of welfare, pensions, the rights of trade unions, arts and food subsidies, rents, housing, the price of milk and what you could buy in the corner shop. It involved one currency replacing the other, dismantling the East’s vast internal intelligence network with all the nightmarish revelations that would have to bring, fundamental alterations to newspapers, magazines and television. And then there was the shoot-to-kill policy at the wall, something else with nightmarish consequences.

More than all this, the takeover touched everything people thought: how life worked and why it worked like that, what was normal and what abnormal, what society was and was not, what you knew and what you didn’t know, what you could do and what you couldn’t. All these were subject to questioning in the East as the GDR began to break up, the economy floundered and significant proportions of the population – bemused, disorientated, disenchanted and prey to every neon sign beckoning from the West – were ripe for the ingestion.

I repeat: nothing like this had ever been tried before, and anyway, the divisions had seemed too deep and too permanent. Two distinct normalities had matured down the years, fostering two distinct personalities, and they had very few points of contact, physical or intellectual. Ordinary Easterners watched Western TV, which was and wasn’t a point of contact but – except pensioners, being sometimes allowed to attend significant family events or officially sanctioned trips – they couldn’t visit the West. Moreover, Westerners found the GDR unattractive and chose more exotic destinations except when they visited relatives bearing gifts, making even that point of contact problematical in terms of Eastern resentment. There were no plans for the reunification and as the people danced on The Wall nobody knew what was going to happen next.

While it stood, The Wall confirmed every stereotype about itself because, mute and brutal, it could do nothing else.

When Hitler pulled the trigger Germany was a devastated corpse which the victorious Allies dissected into their own zones: the Soviet Union took the east; the British, Americans and French took the west. Berlin, 120 miles inside the Soviet Zone, was cut into four sectors in the same way.

By 1949 the Cold War had chilled to the point where the western parts became the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) and the eastern part the GDR, each created in the image of its conquerors. (The FRG, incidentally, was sometimes known as West Germany and the GDR as East Germany. I have used the initials throughout although when interviewees spoke of West and East I left that alone. You know exactly what they mean. I have also used a capital W when people mean the West in general, and the same for the East.)

The chill deepened and geography became central. To prevent the GDR disintegrating by mass emigration its government erected what became known as the Iron Curtain from the Baltic to the Czech border, although Berlin remained an anomaly because it was inside the GDR but under four-power control and therefore open.

The Soviet Sector became the capital of GDR, despite the fact that the other three powers did not recognise this. The Western sectors became West Berlin; part of the FRG but with a special status. The post-war settlement would be expressed in geography and geometry.

The flight from the East, easy in Berlin where all you had to do was walk across the street to the West or board an underground train, ceased in August 1961 when the GDR built The Wall through the middle of the city and continued it into the countryside, round West Berlin in a tight embrace. From then on, the real divergence began and by 1989 people in their late twenties on either side had lived their whole lives with it. This is important. In the FRG, from the 1960s, only small majorities thought unification a real possibility and by 1987 this had fallen to 3 per cent. Evidently the situation was the same in the GDR. The Germans on both sides, confronted with a realpolitik hardened by the passage of time, accepted the division and lived with it. In a 1984 survey, 83 per cent of the FRG’s citizens accepted the existence of two German states, although 73 per cent said Germans were one people.5

Rudolf Bahro, a perceptive GDR Party member whose free thinking led him into exile in 1979, said in 1980:

You find that workers will grouse and swear about conditions when they are in their factory, but when some well-heeled uncle arrives on a visit from West Germany, they stand up for the GDR and point out all the good things about it, all the disadvantages they had to overcome after 1945, and so on. Although the state’s demands for loyalty are widely resented, I would say that in normal, crisis-free times there is a sufficiently high degree of loyalty to assure the country’s viability.

Bahro said in 1983: ‘The Soviet Union has specific reasons for wanting to hold on to East Germany and, in view of the proximity of NATO and West Germany, would never allow any experiment in the GDR unless it were an absolutely safe manoeuvre. So an opposition there has no possibility of crystallizing.’6

Bahro, of course, was speaking before Mikhail Gorbachev’s liberalisation. His words reflect – accurately, I am sure – the position when he spoke them. They are valuable for that reason, and valuable also because they show the extent of the change to come.

Another perceptive German, Peter Schneider, set out (in 1990) the position from the West. ‘No one wanted to admit it, but we saw and treated East Germans as foreigners; in fact, according to polls, a majority of young people defined East Germany as a foreign country.’ He broadened that, asking rhetorically how a Pole from Warsaw could communicate with a cousin in Chicago after decades of enforced separation in different systems. He pointed out that other politically divided countries – China, Vietnam, Korea – provoked the same question: a Chinese man from Hong Kong meeting his uncle from Beijing; a Cuban boxer meeting someone who had fled in a Miami bar.7 They spoke the same language but could they communicate, which is not the same thing at all? Could the Germans?8

The depth of the divergence between the GDR and the FRG remained, for all this, an academic question; unquantifiable, uncharted, problematic and distantly intriguing until 1989. Then, very suddenly, and from almost nowhere, it arrived with irresistible momentum. There were clues about the depth, visible clues. West Berlin, fattened by subsidies from the FRG, exuded prosperity. It had been extensively rebuilt after the war and its widest avenue, Kurfürstendamm, contained shops to rival any in London, Paris, New York or Tokyo. West Berlin was lively, cosmopolitan, edgy, happening – spiced by student vitality, bohemians, military drop-outs and artists as well as a lot of solid businessmen making money. It had, too, a frisson of danger because the Red Army was just over there.

Far from being fattened by subsidies the GDR was starved because the Soviet Union demanded, and took, enormous reparations after the war. Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawn has written that the country had

a monstrous all-embracing bureaucracy which did not terrorise but rather constantly chivvied, rewarded and punished its subjects. The new society they were building was not a bad society: work and careers for all, universal education open at all levels, health, social security and pensions, holidays in a firmly structured community of good people doing an honest day’s work, the best of high culture accessible to the people, open-air leisure and sports, no class distinctions.

Hobsbawn goes on to point out that the ‘drawback, apart from the fact, unconcealable from its citizens, that it was far worse off than West Germany, was that it was imposed on its citizens by a system of superior authority … [People] had no control over their lives. They were not free.’9

Another historian, Mary Fulbrook, has written that when The Wall fell ‘Westerners were aghast at the state of East Germany: the crumbling housing; the pot-holed, cobbled roads; the brown coal dust and the chemical pollution in the industrial centres of the south; the miserable offerings in the shops, the relative paucity and poor quality of consumer goods …’10

It seemed clear from the West: communism had failed and Easterners would quickly satisfy their subterranean desires by becoming Westerners themselves.

It seemed clear from the East: nothing was clear any more.

Regardless, the third and final part of Hitler’s war – putting Germany back together again – had begun. This is the story of what happened to people in the midst of that over the ensuing twenty years, as the first generation who had known nothing but unification reached adulthood. It does not pretend to be a text book, teeming with statistics, pie charts, graphs and the rest. It’s about people chosen to illustrate as many experiences as possible and from both sides of the long-vanished Wall: a sequence of insights from the ordinary players caught up in a unique drama. Their experiences may or may not be typical and in these circumstances perhaps no experiences could be. There is, I hope, enough solid information to give the interviews their true contexts. The chapters cover a lot of territory, too – in order: The Wall, religion, the artists, the property nightmare, health, teaching history, the police, the army, the unemployed and Dresden, a unique city bearing the full weight of Germany’s past, present and future.

Hitler remained a presence, a darkened background spectre, even as Germany was being put back together and, moving towards twenty years since the fall of The Wall, he suddenly emerged in the foreground. An affiliate of Madame Tussauds was established in Berlin and included a wax dummy of him in his last days. It was inevitably a very controversial matter because it invited Germans, as they shuffled by, to face – literally as well as figuratively – the demons of their own past.11

Madame Tussauds opened and the second visitor in vaulted the rope cordon, seized Hitler and wrenched his head off (the body was fibreglass, the head beeswax). As the man, described as a forty-one-year-old former policeman, was wrestled by security staff he shouted ‘never again war’. He added he was delighted it had happened in the presence of the waxwork of Willy Brandt, who fought the Nazis, was mayor of West Berlin when The Wall went up and became FGR Chancellor.

This is the story of many, many other people wrestling their demons.

Notes

1. ‘Die Mauer wird in fünfzig und auch in hundert Jahren noch bestehen bleiben, wenn die dazu vorhandenen Gründe noch nicht beseitigt sind.’ (The Wall will remain fifty and even a hundred years if the reasons that led to it are not removed by then.)

2. The GDR held local elections on 7 May and these were subsequently discovered to have been fraudulent, provoking simmering rage within the country for all the obvious reasons. Ordinary people had had enough of the 98.85 per cent approval, a percentage unthinkable in any properly democratic country.

3. The mechanism of unification was to use Article 23 of the FRG’s Basic Law, which could be implemented quickly – Chancellor Helmut Kohl evidently feared circumstances might change, thwarting the whole thing. This did mean, however, that the GDR was absorbed into the FRG model. The alternative would have been to use Article 146.

Ms Kubisch explains: The basic law for the FRG (in its old version) offered two possibilities for reunification: by the accession of other parts of Germany to the territory of the FRG according to Article 23 or through a new constitution according to article 146, which would have to be decided by the German people.

Article 23: ‘Dieses Grundgesetz gilt zunächst im Gebiet der Länder Baden, Bayern, Bremen, Groß-Berlin, Hamburg, Hessen, Niedersachsen, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Rheinland-Pfalz, Schleswig-Holstein, Württemberg-Baden und Württemberg-Hohenzollern. In anderen Teilen Deutschlands ist es nach deren Beitritt in Kraft zu setzen.’

[This basic law applies in the first instance to the area of the Länder of Baden, Bayern, Bremen, Groß-Berlin, Hamburg, Hessen, Niedersachsen, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Rheinland-Pfalz, Schleswig-Holstein, Württemberg-Baden und Württemberg-Hohenzollern. It is to be brought into effect in other parts of Germany after their accession.’]

The decision for an accession rather than a new state constitution was actually made during the first free elections in the GDR on 18 March 1990. The majority of GDR citizens voted for those parties that were in favour of accession according to Article 23. Correspondingly, the People’s Chamber decided on 23 August 1990 for GDR accession to the territory of the Basic Law effective from 3 October 1990.

Article 146

(Duration of validity of the Basic Law)

This Basic Law, which since the achievement of the unity and freedom of Germany applies to the entire German people, shall cease to apply on the day on which a constitution freely adopted by the German people takes effect.

4. Der Vertrag: Wie ich über die deutsche Einheit verhandelte, Schäuble.

5. Figures in Rewriting The German Past.

6. From Red To Green, three interviews with Rudolf Bahro.

7. The German Comedy by Peter Schneider. Capitalist Hong Kong and communist China were reunited in 1997, although this was not comparable to the two Germanys because Hong Kong was a British colony, not an independent country recognised by the United Nations. A more apt comparison would be uniting communist China and capitalist Taiwan – which has not happened. Korea, of course, remains separated and more bitterly so than the Germanys ever were. North and South Vietnam were essentially peasant countries, the North finally overrunning the South in 1975. The South did not vote itself out of existence.

8. An example of this is the simple word freedom. To a GDR citizen it might mean freedom from unemployment, freedom from the tyranny of rents you couldn’t afford, freedom from inflation, freedom from anxiety over medical bills. To an FRG citizen it might mean freedom to vote for different parties, freedom to travel, freedom to read, write and say whatever you wanted. I can’t resist a little joke built upon this: capitalism is the exploitation of man by man, communism just the opposite.

9. Interesting Times, Hobsbawm.

10. The People’s State, Fulbrook.

11. Birgit Kubisch points to a much more mundane consideration: Germany has no history of waxwork museums and depicting people, any people, like that would be controversial.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks primarily to Birgit Kubisch, without whom this book wouldn’t have happened; she took the photographs. She was instrumental in finding many of the subjects for interview, organised everything in Berlin, handled a great deal of research, translated background and interpreted. She also read the manuscript pointing out errors along the way, as did John Woodcock, an old friend, Berlinophile (if I can invent a word) and professional journalist. He contributed questions to several interviews and wrote a perceptive description of the GDR Museum (see Afterword).

The following were kind enough to give interviews: Hagen Koch; the late Dr Johannes Althausen; Pastor Christian Müller; Father Gregor Hohberg; Thomas Motter; Peter Unsicker; Claudia Croon; Heike Herrmann; Fulvio Pinna; Dr Ellen Händler (Press Officer, BVD); Dr Wolfgang and Inge Bringmann; Dr Ulrich and Anne Bartel; Kerstin Paust-Loch and Rudolf Loch; Richard Piesk; Dr Falk Pingel, deputy director of the Georg-Eckert Institute for International Textbook Research, Braunschweig; Dr Alan Russell, co-founder of The Dresden Trust; Dresden resident Cornelia Triems-Thiel; Christoph Münch, Dresden Marketing GmbH i.G.; Marion Drögsler, chairman, Arbeitslosenverband Deutschland e. V; Detective Police Commander Bernd Finger, Criminal Investigation Department, LKA 4; Dr Rüdiger Wenzke MGFA, Potsdam; Manuela Damianakis, Head of Press Office, Senate Department for Urban Development; policemen Frank Thomas and Raymond the border guard; Birgit Hartigs of the Undine Wohnprojekt; Angelika Engel; Regina S. and Friedrich E. of Sozialwers des dfb, Berlin; Brigitte Triems; Yvonne Triems; Marcel Franke; Constanze Paust; Dagmar Althausen who helped find interviewees, and to Axel Hillebrand.

Professor Dr Norbert Walter, Chief Economist with the Deutsche Bank Group, has kindly allowed me to quote from a penetrating and authoritative article he wrote in the American Institute for Contemporary German Affairs. Dr Dorothea Wiktorin (Department of Geography, Cologne University) has written a notable study on the property problems and has kindly allowed me to quote extensively from it. Gregory Pedlow, Chief, Historical Office, Command Group, SHAPE, gave an invaluable insight into the united German army within NATO. Professor Norman Blackburn kindly granted permission to quote from his essay on Dresden in the book Why Dresden? An article in Contemporary Review 12/1/2000 by Dr Solange Wydmusch was extremely helpful in providing background for Chapter Two. Many other sources have been quoted, covering the important aspects of unification, and these are fully acknowledged in the footnotes and Bibliography, but two in-depth studies were particularly invaluable, Education in Germany since Unification (edited by David Phillips) and Divided in Unity by Andreas Glaeser. I have leant heavily on them and I am extremely grateful to Associate Professor Glaeser, of the Social Sciences Department at the University of Chicago, for permission to quote. Thanks to Dresden-Werbung und Tourismus GmbH (Praktikant Marketing) for a map of the city, and especially Cornelia Sanden for visitor statistics. Kristina Tschenett, Press Officer, Senatsverwaltung für Finanzen provided information on the land at the Wall. Miriam Tauchmamnn, Press Officer, Police President was an invaluable conduit to Commander Bernd Finger.

All unsourced direct quotations in the text are from interviews with the author.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

For those who are not German experts:

The GDR had effectively three leaders (general secretaries of the all-powerful Socialist Unity Party): Walter Ulbricht (1950–71), Erich Honecker (1971–October 1989) and Egon Krenz (October–December 1989). I don’t include Hans Modrow (1989–90) or Lothar de Maizière (1990) – who were Chairmen of the Council of Ministers – because in their time the country was disintegrating. They inherited the endgame.

The GDR state security organ was called the Ministerium für Staatssicherheit (Ministry for State Security), usually abbreviated to the Stasi.

The period when the GDR collapsed is sometimes known as the Wende, the turn.

West Germans are sometimes called Wessis and East Germans Ossis, giving a wonderful play on words, Ostalgie – Easterners’ nostalgia for the GDR.

The FRG was organised into ten Länder (or states) and on unification the GDR was divided into five (Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Brandenburg, Sachsen-Anhalt, Sachsen [Saxony] and Thüringen). The two halves of Berlin formed a sixteenth.

The main shopping thoroughfare in West Berlin was the Kurfürstendamm, often abbreviated to the Ku’damm.

TIMELINE

1945

7 May

Germany surrenders

3 July

Allied troops take over their four sectors in Berlin

16 July

Potsdam Conference begins

2 August

Potsdam Conference ends

1946

21 April

Communist Party and Social Democrats form the SED (Socialist Unity Party) to rule East Germany

1947

5 June

Marshall Plan launched

1948

21 June

Deutsche Mark introduced in the West

24 June

Berlin blockade and airlift begins

24 July

East German Mark introduced

1949

4 April

NATO formed

11 May

Berlin blockade and airlift ends

24 May

FRG (Federal Republic of Germany) founded in the West, merging the American, British and French Zones

7 October

GDR (German Democratic Republic) founded in the East from the Soviet Zone, with East Berlin as its capital

1953

16 June

GDR workers uprising over increasing work norms

1955

9 May

FRG accepted into NATO

14 May

Communist states, including the GDR, sign the Warsaw Pact

1958

27 October

Walter Ulbricht, GDR leader, threatens West Berlin

10 November

Soviet leader Nikita Khruschev says it is time to cancel Berlin’s four-power status

1961

4 June

At a summit in Vienna, Khruschev tries to pressure US President John Kennedy to demilitarise Berlin

1–12 August

21,828 refugees arrive in West Berlin

13 August

Berlin Wall built

1963

26 June

Kennedy visits Berlin and makes his ‘Ich Bin Ein Berliner’ speech

1968

21 August

Warsaw Pact countries crush Prague Spring

1970

19 March

Willy Brandt visits GDR city Erfurt as part of his Ostpolitik policy

1971

3 May

Ulbricht forced to resign, succeeded by Erich Honecker

1972

October

Traffic Agreement signed, giving FRG citizens access to the GDR

21 December

Basic Treaty signed, the FRG in effect recognising the GDR

1973

18 September

The GDR and the FRG admitted to the United Nations

1985

11 March

Mikhail Gorbachev elected General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party

1987

12 June

Ronald Reagan speaks at the Brandenburg Gate: ‘Mr Gorbachev, tear down this wall.’

7–11 September

Honecker visits FRG

1989

2 May

Hungary opens its border with Austria, allowing GDR holidaymakers to cross

7 May

GDR elections with 98.85 per cent for the government and widespread allegations of fraud

4 September

Leipzig demonstrations begin

30 September

GDR citizens in FRG Prague Embassy told they can travel to the West

6 October

GDR fortieth anniversary

18 October

Honecker forced to resign, succeeded by Egon Krenz

4 November

A million people demonstrate in East Berlin

9 November

The Wall opens

29 November

Chancellor Helmut Kohl issues plan for a ‘confederation leading to a federation in Germany’

7 December

Krenz resigns. GDR government meets opposition parties

8 December

SED Congress elects a new generation of leaders

19 December

Kohl visits Dresden, crowds chant ‘we are one people’.

1990

18 March

Free GDR election, Christian Democratic Union gain 40 per cent of the vote

1 July

Currency union

3 October

Germany reunited

Map 1. The postwar division of Germany with Berlin isolated deep in East Germany (the GDR). Poland was given German territory up to the Oder.

Map 2. The postwar division of Berlin: the East – the Soviet Sector – becoming the capital of the GDR; the three Western sectors surrounded by the GDR. The French were in the north, the British in the centre and the Americans in the south. The numbers show where the checkpoints through The Wall were: 1 – Bornholmer Strasse; 2 – Chausseestrasse; 3 – Invalidenstrasse; 4 – Friedrichstrasse (Checkpoint Charlie); 5 – Heinrich-Heine-Strasse; 6 – Oberbaumbrücke; 7 – Sonnenallee.

1

HISTORY LESSONS FROM THE WALL MAN

You don’t know it, and most Berliners don’t either, even as a name. Leuschnerdamm is an ordinary street bearing no obvious resonance.

Occasional pedestrians – reflecting, inevitably, the colours and dress codes of a modern international city – walk by just as they walk by everywhere else. This day an African woman with two heavy shopping bags plods forward on her eternal journey. A couple hold hands and giggle, a limitless future in front of them. Cyclists, invariably young women and some towing two-wheel kiddiekarts, pedal by, slender legs pumping evenly. The traffic is light.

On one side of the street, cars are parked flank-to-flank in the white boundary bays painted across cobblestones, an ordinary arrangement for parking. A terrace of tall buildings, all apartments except a couple of entrances to businesses, looms behind them. Each house has a small garden and some tall trees give privacy as well as a certain charm. On the other side of the street, a low brick wall masks sunken gardens immediately behind it. They are immaculately maintained and offer an arbour of calm: benches where people sit and eat their sandwiches, doze or chat, pathways where joggers grunt and pant. Further away the breeze ruffles a surprisingly large artificial lake but the brick wall masks that, too, because it is sunken to the same level as the gardens.

Leuschnerdamm rests, like a thousand others, in the great web of Berlin streets and if you walk it, which will take four or five easy minutes, you’ll probably have forgotten it when you reach the far end. It’s so slight – a curve straightening towards a bridge – that you have to strain to see it on maps, and anyway, maps are devoid of meaning now except in terms of orthodox cartography. The maps have become mute but once they screamed.

Leuschnerdamm has had four distinct locations although it’s always been exactly where it is. That’s a very Berlin situation created by commerce, war, defeat, chance and geometry; the sort of situation which in any other city anywhere would make it resonate as a freak, a tourist attraction, a former potential battleground, a site of genuine historical importance and, in the sane world, an impossibility. That it has become ordinary is Berlin.

There are three resonances but you have to deduce two of them and deliberately pause to see the third. The first is the pavement in front of the apartments. It comprises old, uneven slabs with a patchwork of running repairs which form a slightly unkempt mosaic. This is the sort of thing which offends the German sense of order and propriety, and you’d have expected it to be completely re-laid years before. What can it mean that it hasn’t been?

The second is a sequence of holes bored into the cobblestones and filled with black tarmacadam. They are a little way from the lip of the pavement, are equidistant and in a row. They follow the curve, follow the straightening towards the bridge but, just in front of it, cross to the side of the brick wall. What can that mean?

The third will tell you. A black and white photographic display has been arranged in the window of one of the businesses. It is easy to walk past it and most do. The cyclists and motorists never see it at all. You have to stand, peer and concentrate because one photograph, a panoramic view, gives you everything all at once. It is so stark it does not require a caption and, like emerging from sunlight, your eyes need time to adjust. At first it seems to be a lunarscape with houses – the apartments – but as your eyes adjust it transforms itself into the Leuschnerdamm which was somewhere else altogether: depending on which side chance had placed you, a frontier community confronting Ronald Reagan’s evil empire or a frontier community confronting the imperialist-fascist-capitalist running dogs.

The Wall ran where the dark tarmac holes are – they were supports for an earlier version of it – so the terraced houses and the unkempt pavement were in the West, the cobbled road in the East. The pavement became a gully; the 12ft Wall to one side of it, the apartments and their little gardens to the other. The pavement was wide enough for pedestrians but not for delivery vehicles and access had to be from the rear of the apartments. There’s no doubt why the pavement was neglected. Re-laying it would have been logistically difficult and few people used it anyway – the residents, mostly. It might have been a private, forgotten fragment of West Berlin, darkened by the trees.

In the photograph, the little brick wall, the sunken gardens and the lake appear as a broad area of perfectly level, raw, raked earth forming the death strip. Apart from a couple of mushroom-shaped watch towers there is nothing on the Eastern side of the Wall but emptiness. Nothing.

The fall in November 1989 altered all that. The lake has been excavated (it was filled with rubble from the bombed buildings after the war, hence the chance to create the level ground) and now offers a wooden platform like an inland jetty – decking – with tables and chairs, and a mini-restaurant. Pretty waitresses flit to and fro. It’s popular with people who take lunch, like a glass of wine, a beer or a coffee. Stones, arranged like a rockery, butt up against the jetty’s lip and some turtles live down there. Their shells are the same colour and shape as the stones so that, astonishingly, even when you are close to them you can’t always pick them out. Sometimes they lower themselves deftly into the water and chug off, their little dark heads bobbing to the surface, going under, bobbing up again.

Emboldened sparrows scour for crumbs. A lawnmower moans from the sunken gardens.

Opposite Leuschnerdamm, ringing the other side of the lake, another terrace of apartments has been built where The Wall ran. This street, Legiendamm, is a parallel shape to Leuschnerdamm and thus its twin. The buildings, pleasantly pastel-shaded, radiate a modern style and confidence.

Jochen Baumann moved from the Western town of Freiburg to Leuschnerdamm in November 1989, when The Wall still stood, because ‘I wanted an alternative lifestyle’ and Kreuzberg offered that. The fact that The Wall was there kept rents low. Now, autumn 2008, ‘this is still the poorest area … in the whole of Germany so you have here a clear confrontation between the poorest and the new rich ones. The new rich ones are looking across from the East to the poor ones in the West …’

Legiendamm is clearly a desirable location: central, affording a most charming vista of the sunken gardens and the lake. You can imagine estate agents feasting on it, emphasising how wholesome the area is, how nice. The estate agents probably won’t be mentioning maps because it gets complicated. For logical reasons Leuschnerdamm used to be called Elisabethufer and Legiendamm used to be called Luisenufer. Ufer means shore: the roads ran along either flank of a waterway which linked the distant River Spree to the distant Landwehr Canal, passing through the lake along the way. Barges plied their trade along it quite normally, from river to canal and back again.

Think Amsterdam and you get the idea.

In 1926 the waterway was filled and made into gardens so the shores no longer existed, and the street name changed in parallel, because damm means something built up – in this case, filling the waterway. The lake, however, remained; isolated now.

You can trace the story of most European cities through what streets and squares are called, ranging from original purpose (Middle Way, Flower Street) through place associations (Dresden Street, Frankfurt Alley) to notable figures (Alexander Square, Friedrich Street). Then there are the politicians, who may or may not be notable. The names usually act as a kind of record, a continuum, from the mists of the past to the near-present. One Berlin problem remains that all too often they don’t. In 1947 both names changed.

Luisenufer became Legiendamm after Carl Legien, a trade unionist. The East Germans rarely resisted the chance to impose old left-wing heroes on the street names and, in the end, did it in profusion. After reunification, this meant trouble. The point, however, is that very rarely have streets in European cities carried an ancient name from the mists, been suddenly renamed something completely different and then just as suddenly reverted to the original. After 1989 it would happen all over East Berlin, the streets and squares becoming a record of history reversed.

Elisabethufer became Leuschnerdamm after Wilhelm Leuschner, a trade unionist, demonstrating that West Berlin was not averse to imposing old left (but never, of course, right) wing heroes on the street names, although it usually resisted the temptation.1

If you saw The Wall on any day between Sunday 13 August 1961, when it went up, and Thursday 9 November 1989, when it came down2, Leuschnerdamm and its twin will be readily intelligible to you.

Berlin had always been isolated on the Brandenburg plain towards the Baltic, much nearer Poland than Western Europe. That made it awkward when the Allies came to divide Germany into their own zones – American, British, French and Soviet – at the war’s end. Berlin would lie deep inside the Soviet Zone and it, too, was to be divided, but into sectors – again American, British, French and Soviet – using the city’s twenty ancient districts. The Soviets took the eight in the east and centre, the French the two in the northwest, the British the four opposite the centre and the Americans the six in the south-west.3 The fact that the boundaries were ancient became awkward in itself because the city had naturally functioned as a whole, the boundary lines between the districts signifying nothing physical. Down the centuries the city grew over them like any other city. The terraced apartments in Leuschnerdamm happened to be in the Kreuzberg district (under American control), the cobbled road in Mitte (under Soviet control).

The arteries keeping West Berlin alive would become the autobahns and railway lines crossing the Soviet Zone from the West. They were, of course, vulnerable to the shifting climates of the Cold War because they could be blocked so easily and quickly, but that wasn’t foreseen in 1945, not with the Soviets as gallant comrades in arms; not with Uncle Joe Stalin beaming benevolence.

In 1949 the three Western zones became the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) and in response Stalin formed his zone into the German Democratic Republic (GDR). There were legal niceties here. As the whole of Berlin was under Allied control, the city ought to have remained separate from the two new Germanys, and the American, British and French Sectors did, forming West Berlin. The Soviets ignored this and made their eight districts into the capital of the GDR – something the West did not accept. They retained the right of free access to East Berlin and, from 1961 to 1989, sent daily patrols across in jeeps to protect and perpetuate that right.

Map 3. The Wall at Leuschnerdamm, showing how the death strip was created by levelling gardens, a lake and a road. Note how The Wall ran between the two churches, bisecting their communities.

Map 4. Leuschnerdamm after The Wall and even imagining it has become extremely difficult.

The FRG prospered and the GDR prospered, but on a more modest scale, and the unflattering comparison was always there as well as the politics. That produced a rising tide of refugees and the only way to staunch it was a physical barrier. It would have to measure 99 miles (156 km), of which 66 (107) were concrete, the rest wire mesh.

If you haven’t visited Berlin you need an aerial picture in your mind: The Wall encircled West Berlin like a noose, looping through the countryside beyond the Western suburbs then running through the city following exactly the extent of the Soviet Sector there. That’s why it zigged and zagged. Inevitably it created anomalies and absurdities amidst the human misery of sudden separation: 192 roads, gardens and allotments were bisected, the underground system, too. Along one street, Bernauer Strasse, if you stepped out of your house you left the GDR and entered West Berlin. At the end of Bernauer Strasse the entrance to the underground station lay in West Berlin, the platforms in the East. Now multiply this by the twenty-eight miles which The Wall zigzagged through and a very strange aerial picture should be forming.

The Wall is convenient shorthand for what it really was: a fortification of medieval character and mindset. The outer Wall, the one in all the photographs – 12ft high (3.6m) and of interlocking slabs with the curved pelmet on top to hamper grip – faced West Berlin. The death strip stretched behind it, every yard covered by watchtowers. The inner Wall uncoiled at the far side of the death strip so anyone fleeing had to climb this, sprint across the strip and get over the 12ft Wall. There were refinements in the death strip, like patrol jeeps, attack dogs, tank traps, scatter guns with tripwires and, according to rumour, concealed mines. There were obstructions, like the Church of Reconciliation in Bernauer Strasse, which was isolated within the death strip and eventually blown up. Part of its cemetery fell within the death strip too, and soldiers exhumed graves and moved them. From north to south, and for the twenty-eight miles, the death strip was the level, raked, raw earth or sand affording no cover to a running man – or woman.

The width of the death strip was governed by the space available, itself dependent on the ancient boundaries. In some places, for example where the lake had been beside Leuschnerdamm, it extended over a considerable area; in others it was as narrow as the road between two rows of houses. And that’s the way it was from 1961 to 1989, by which time a whole generation had been born and grown up in the GDR who had known nothing else and virtually none of whom had seen West Berlin, never mind set foot in it.4 They have now been able to set foot in it for going on two decades, and nothing could look more normal than Leuschnerdamm or those who sit on the jetty and sip a pleasantly chilled glass of white wine delivered to the table by a pretty waitress.

There’s a repetitive saying about The Wall in the Head, meaning virtually all the twenty-eight miles of it have gone yet it remains in people’s minds – an insidious mental barrier and maybe even harder to cross than the physical one. You still find East Berliners who feel West Berlin is somewhere else, and West Berliners who feel the same about the East. On one and the same day, Birgit Kubisch and I spoke to a man in the West who said ‘our taxes are financing the East, that’s where all the development is’ and a man in the East who insisted ‘the West is keeping all the money, look at all the new buildings there’. New buildings are going up everywhere and the city will continue to resemble an industrial site for a generation, but both men had persuaded themselves this wasn’t really happening. They couldn’t get their minds round The Wall in their minds.

It is true the physical Wall has gone except for what you might call extended fragments: a section at Bernauer Strasse and a longer section called the East Side Gallery bordering the River Spree. Once upon a time, after the fall, artists apportioned their own parts of this, using the vertical slabs as canvas, and created witty, perceptive murals: Honecker kissing Brezhnev, a Trabant bursting through, invocations to peace and love, that sort of thing. Then the graffiti raiders came with their childlike slogans and kindergarten shapes, and now it’s a dreary procession of nihilism, more sad than evocative; a wall in a slum.

The sightseers are drawn, or taken, to Checkpoint Charlie, known throughout the world between 1961 and 1989 as the microcosm of ultimate confrontation. Here the two dominant power blocs of the twentieth century came face to face every hour of every day at what had been a resolutely ordinary intersection between a side street and an avenue. A plain white line across the avenue delineated the exact place of division. No other city on earth had so many of its basic functions dictated by geometry.

Remember, the West did not recognise the GDR or East Berlin as its capital, and under the post-war settlement Berlin remained one city, at least in theory. The Western side of Checkpoint Charlie reflected this because, in the middle of the road, a modest military hut operated no control over anyone going to the East or coming back. Beside the hut a tall sign announced in English, French and Russian that you were leaving the American Sector. That was all.

The Eastern side reflected the reality with an entrance through The Wall covered by watchtowers, a sprawling control system under an awning like an aircraft hangar with lanes for vehicles and pedestrians, then low buildings where you handed your passport through an aperture to be inspected, verified and stamped by hands you couldn’t see, then a wave of a border guard and you could proceed into East Berlin.

Checkpoint Charlie did resonate as a freak place, a tourist attraction, a potential battleground – in 1962 Soviet and American tanks did come literally face to face here – a site of genuinely historical importance and, in the sane world, an impossibility. That it never became ordinary is Berlin, too.

It has gone now, replaced by a skyscraper, an office block or some such building; big, new, glistening and anonymous.

There are other fragments: a hut remains in the middle of the road, a hoarding with pictures on it tells the tale, the famous museum dedicated to Wall escapes still overlooks where the checkpoint was. Ironically, the fall of The Wall – to select just one example – restored Leuschnerdamm’s death strip to life but brought an emptiness to Checkpoint Charlie. The sightseers mill and wander, guides in a dozen languages give their commentaries, and everybody looks completely lost. Who can imagine today that at this intersection, with ordinary traffic ebbing across like at every other intersection, an armed encampment was just here, watchtowers manned by guards who would shoot to kill were just there, there and there, that The Wall ran just that way down there and this way down here? – that just over there a young East German, Peter Fechter, was shot and left to bleed to death?

There’s a souvenir-cum-bookshop incorporated into the museum and the pleasant young assistant explains that the sightseers always ask the same questions: ‘Are the little chunks of The Wall on sale here real?’ and ‘where can I see it?’ You can’t, unless you go to Bernauer Strasse or the East Side Gallery and even there you won’t be getting the old impact. For the full experience you’d need the real thing and that’s as dead as the cemetery in Bernauer Strasse – or it would need to be in your head, and for that you’d have to be a Berliner.

At the intersection a kiosk rents out taped commentaries so you can follow the course of The Wall, and there’s an artefact to aid you, a twin row of cobblestones which charts its course exactly, re-enacting the geometry. The cobblestones are set into roads and pavements, which produces a particular irony because now cars can drive over them and pedestrians can walk over them quite normally, even though they mark something so tall people couldn’t see over it and couldn’t cross without risking their lives.

You might imagine that the cobblestones would faithfully follow the entire Wall, so you could start in the north of Berlin and finish in the south retracing every foot of it, but you can’t. Sometimes new buildings straddle it and sometimes it’s just not there. Leuschnerdamm has its original cobblestones, the ones with the black tarmac holes in them, but no twin row.

It spawns a joke: we’re in Kreuzberg – home of the Turkish community, the avant garde, the bohemian and the dubious – and who ever remembers us?

The route from Kreuzberg to Checkpoint Charlie is tortuous, with and without the cobblestones marking the way. If you turn right at the top of Leuschnerdamm and cross the bridge you’re in Waldemarstrasse; the buildings to the left in the West, Legiendamm and the wide, cleared death strip to the right. Nature had reclaimed it so completely that it resembles a jungle, an astonishing sight in the middle of a modern city where every square metre is precious, finite and worth a fortune – until the inevitable diggers come, and work on foundations for another high-rise to begin.

The death strip still cuts its great zigzagging swathe, an equally astonishing sight in a city of today. Because the inner and outer walls have gone the strip is a mysterious place, meaningless in a modern context and, until the developers get their hands on it – as they are beginning to do – useless to all except wildlife and dog walkers. At the end of Waldemarstrasse, where new buildings are coming up like mushrooms, the death strip crosses the road into more jungle, so overgrown that you have to stoop and duck if you follow the ribbon of patrol road the military jeeps used. If you are intrepid enough you’ll reach Heinrich-Heine-Strasse where a checkpoint used to be and where, one distant day, President Richard Nixon came for his feel of The Wall. Like Checkpoint Charlie the buildings have all gone but its tall, curving arc lamps remain, illuminating a car park.

Before the GDR, the avenue was called Prinzenstrasse, innocuous enough and ideal for renaming. The GDR did not exclusively reach for communist and anti-fascist figures and figurines for its thoroughfares. Heinrich Heine (1797–1856), a German Jew from Düsseldorf of impeccable middle-class credentials – father a merchant, mother sophisticated, and money in the family – became a lyrical romantic poet. Cumulatively, Heine was a long, long way from the GDR but it had several goals which it pursued implacably, and culture was one of them.

After reunification, when the reverse-history began to rename the renamed streets in the East, trouble in many guises and nuances did arrive very quickly. We’ll be coming to that. It would, however, be bad news for many great German heroes of the revolution, and Ho-Chi-Minh-Strasse had no chance (it was named that in 1976, reverted to Weißenseer Weg in 1992).

Heinrich-Heine-Strasse survived, Prinzenstrasse presumably gone forever (in the east; the western part remained and remains Prinzenstrasse) this second time round, and there the avenue remains: long, ramrod straight and with everyday traffic flowing along it, as resolutely ordinary in its way as Leuschnerdamm or the junction which became Checkpoint Charlie. Of course, to call an avenue after a lyrical poet where border guards had orders to shoot to kill might be regarded as deliberately provocative, but it wasn’t. It was just Berlin, abnormality co-existing with normality in an adaptive way.

On the other side of Heinrich-Heine-Strasse the death strip stretches past modern apartment blocks in the West. There are twin roads here, equidistant and with only a hedge of small bushes between them; one road built specifically to give access to the apartments because the other, the original road, which would have done that was just behind The Wall. Both are called Sebastianstrasse.

At the end of Western Sebastianstrasse, which is halfway up Eastern Sebastianstrasse, you turn left, the death strip a jungle again, past a school and on, turning left and right: this is the ancient boundary between bohemian Kreuzberg and the Mitte district, the pride of the East and the historic centre of old Berlin. You’re in amongst tall buildings which have consumed the death strip and you’re walking towards Checkpoint Charlie. It’s a lot of layers and they’re everywhere you look, even if you need a tutored eye to see them.

Many perceptive words have been written about The Wall, and a single sentence by Peter Schneider in his study The Germany Comedy: Scenes of Life After The Wall (1991 – that’s important) has a haunting quality. He broods if ‘it was The Wall alone that prevented the illusion that The Wall was the only thing separating the Germans’. He was introducing the concept that the two Germanys had grown far apart, but as long as The Wall stood a pretension could be maintained that they hadn’t. People could say it was the only thing dividing them.

The truth of it is not in doubt and this book addresses two questions: amid all this bewildering geography and geometry, all these cobblestones and street corners, how far apart were they and, these twenty years later, how close?

One man knows about The Wall and knows about the layers. He painted the original white line at Checkpoint Charlie in 1961 and, one way or another, has devoted the rest of his life to working The Wall then preserving the memory of it. To find him you have to go into the East, to a broad, straight artery called Alt-Friedrichsfelde which still looks like the East – the width of the road dictated by Socialist planning, the great throng of Plan 1 workers’ apartment blocks lining it like sentries guarding the past. Hagen Koch lives in one and although there is ample parking – East Berlin had space – and a few trees for decoration, no real attempt has been made to landscape the grassy area. Socialist planning contented itself with the functional (which was all it could afford anyway). The hall leading to the lift has been repainted, however. It looks fresh and eternally new in the Western way.

There is a resonance on one of the lift’s walls: a montage of small advertisements behind a glass frame. You’re reminded of the classic film Goodbye Lenin