18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

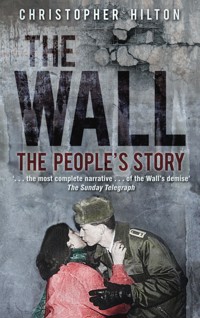

For almost three decades, the Cold War was focused on Berlin, where the two (nuclear-armed) sides were kept apart by a twelve-foot wall, which had appeared almost overnight in August 1961. For a generation, until its fall in November 1989, it not only divided the city of Berlin, but also symbolised the confrontation between capitalist West and socialist East. In this astonishing book, journalist Christopher Hilton has collected together the individual stories of those whose lives it affected, including international politicians, American and British soldiers, East German border guards and, most importantly, the citizens of Berlin itself, West and East. Weaving their memories together into a remarkable narrative, this is the extraordinarily vivid, occasionally harrowing and often touching story of a city divided, and of how it affected the lives of real people.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Contents

Title

List of Maps

Acknowledgements

Prologue

ONE

Fault Line

TWO

Saturday Night

THREE

And Sunday Morning

FOUR

First Week of the Rest of Your Life

FIVE

Cold as Ice

SIX

The Strangeness

SEVEN

The Bullet Run

EIGHT

Thaw

NINE

A Quiet Night Like This

TEN

Dawn

ELEVEN

Pieces

Epilogue: Corridor of Emptiness

Notes

Bibliography

The Death Strip: The Toll

Copyright

Mine is not a pleasant story, it does not possess the gentle harmony of invented tales; like the lives of all men who have given up trying to deceive themselves, it is a mixture of nonsense and chaos, madness and dreams.

Demian, Hermann Hesse

Demian, Hermann Hesse (Panther Books Ltd, London, 1969).

List of Maps

1.The wall, cutting across central Berlin

2.The divided Germany

3.Districts surrounding Berlin

4.Bernauer Strasse

5.The Teltow Canal

6.The River Spree

7.Exits and Entrances

8.The death of Peter Fechter

9.Tunnel 57

10.The Steinstücken enclave

11.The gateways to the West

12.Checkpoint Charlie

Acknowledgements

Any book like this, balancing political and historical background against the first-person testaments of the foreground, draws to itself a lot of people and a lot of sources of information. I pay my due tribute to them all and offer my sincere thanks.

First, Birgit Kubisch, who started off as an interpreter but became an enthusiast, an organiser, a translator, a provider, and handled some interviews herself. To her I must add my neighbour Inge Donnell who moved doggedly through translating the paragraphs of those who died at the wall even though she found the task upsetting; and to her I must add Viktoria Tischer, of Haynes, who set herself to add to the store of knowledge on Peter Fechter, the teenager whose fate – he was left to bleed to death in 1962 – still lives, if I may use that word, in the domain of the grotesque and the barbarous which the Berlin Wall created.

I list the others who helped in no particular order. The book is, I hope, greater than the sum total of its parts – and many, many good people provided those parts, each in their own way. To people who insist that civility, courtesy and cooperation are vanished echoes of a genteel past, I say: wrong. Almost nobody I approached – in so many walks of life – was difficult. On the contrary, and for no reward of any kind, they went out of their way to help.

I owe a special debt to Hagen Koch, a former Border Guard who has, in his cosy East Berlin apartment, set up a museum to the wall because he feels there should be one place where people can find out about it. He has refused a great deal of money for some of the material he’s gathered (including a unique set of photographs of the death strip) and I salute him for that as I thank him for maps, information, and advice. If you want to see for yourself, try http://www.berliner-mauer.de. The Rt Hon. Lord Hurd of Westwell CH,CBE, then British Foreign Secretary, sent specific memories which were gratefully received. Millie Waters, a bubbly public affairs specialist at the HQ US Army, Europe, proved to be a one-person army in finding people and arranging things.

And thanks to the interviewees: Chris Toft, British Military Police; Bernard Ledwidge, British Military Government, Berlin; the late Diana Loeser, who lived in East Berlin; Bernie Godek, Michael Raferty, Bill Bentz and Russ Anderson of the US military; former US Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Frank Cash, Dorothy Lightner (wife of Allan), the late John Ausland, George Muller, Al Hemsing, Richard Smyser and Frank Trinka of the US political and diplomatic services; Adam Kellett-Long (with particular thanks to his wife Mary who allowed me to use extracts from her diary), Peter Johnson (who also let me have his diary) and Erdmute Greis-Behrendt, of Reuters; Günter Moll and Roland Egersdörfer of the Border Guards; Peter Schultz and Ernest Steinke of the RIAS radio station, Berlin; Peter Dick, a Canadian and briefly a West Berlin resident; Peter and Daniel Glau of the Hotel Ahorn, which became a second home; Ekkehard Gurtz, Gerda Stern, Bodo Radtke, Nora Evans, Mateus, Kurt Behrendt, Heinz Sachsenweger, Uwe Nietzold, Erhard and Brigitte Schimke, Lutz and Ute Stolz, Rüdinger Hering, Klaus-Peter Grohmann, Martin Schabe, Horst Pruster, Birgit Wuthe, Jakob Burkhardt, Elli Köhn, Pastor Manfred Fischer, Marina Brath, Astrid Benner, Brita Segger, Katrin Monjau, Harald Jäger, Hartmut Richter, Janet and Jacqueline Burkhardt. E.L. Gordon kept watch on the US media. A friend and fellow enthusiast, John Woodcock, was a valued companion on trips to the city.

There is a Bibliography at the end, but for permission to quote I am indebted to: Edith Kohagen, Editor-in-chief of Presse- und Informationsamt des Landes Berlin for The Wall and How it Fell (1994) and the invaluable Violations of human rights, illegal acts and incidents at the sector border in Berlin since the building of the wall (13 August 1961–15 August 1962), published in 1962 on behalf of the government of the Federal Republic of Germany by the Federal Ministry for All-German Questions (Bonn and Berlin). She also demystified the time gap between Berlin and Washington in August 1961, something not as straightforward as one might imagine. The extracts from Berlin Twilight by Lieutenant-Colonel W. Byford-Jones (Hutchinson), Man Without a Face by Markus Wolf (Jonathan Cape), Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood (Hogarth Press) and The Ugly Frontier by David Shears (Chatto & Windus) are courtesy of the Random House Group Ltd.

I sincerely thank the following for extracts: Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin for Der Sturz by Reinhold Andert and Wolfgang Herzberg; Peter Owen publishers for the quotation from Demian by Hermann Hesse (Panther); A.M. Heath & Co. Ltd for The Ides of August by Curtis Cate (copyright © Curtis Cate, 1978); the Orion Publishing Group Ltd for Willy Brandt: Portrait of a Statesman by Terence Prittie (Weidenfeld & Nicolson); Duke University Press for We Were the People: Voices from East Germany’s Revolutionary Autumn of 1989 by Dirk Philipsen; Continuum for the German Democratic Republic by Mike Dennis; the History Place ([email protected]) for the full text of John F. Kennedy’s speech in Berlin in 1963; Rainer and Alexandra Hildebrandt for Berlin: Von der Frontstadt zur Brücke Europas and It Happened at the Wall; the University of Massachusetts Press for The Wall in My Backyard by Dinah Dodds and Pam Allen-Thompson; HarperCollins for The Siege of Berlin by Mark Arnold-Forster; Sanga Music Inc. for the lines from Where Have all the Flowers Gone? by Pete Seeger; Norman Gelb for The Berlin Wall (Michael Joseph, 1986); George Bailey for Germans: Biography of an Obsession (Free Press, New York) and Battle-ground Berlin (with David E. Murphy and Sergei A. Kondraschev, Yale University Press); the British Army HQ in Germany (and thanks to Helga Heine for smoothing the way) for the Friday 17 November 1989 issue of Berlin Bulletin, the magazine published by Education Branch, HQ Berlin Infantry Brigade for British Forces, Berlin; ITPS Ltd, on behalf of Routledge, for Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century by R.J. Crampton; Christian F. Ostermann, Director, Cold War International History Project, The Woodrow Wilson Center for Scholars Project, for Khrushchev and the Berlin Crisis and Ulbricht and the Concrete ‘Rose’; the Associated Press for their reporting of escapes and escape attempts in the 1980s.

I owe special thanks to Yorkshire Television, for allowing me to quote verbatim from their emotive and emotional documentary First Tuesday on relatives of those who died at the wall. The Bureau of Diplomatic Security of the Department of State, Washington, DC, has allowed me to use a memorandum exploring options before the wall was built, and thanks to Andy Laine for help there as well as the late John Ausland for providing it. Irene Böhme gave permission to quote from her book Die da drüben (originally published by Rotbuch Verlag, Berlin, in 1982) in a charming letter.

Prologue

Commander Günter Moll walked briskly across the concrete concourse which was carpeted by white light falling softly from the banks of tall arc-lamps. He was a small, neat man and, like many professional soldiers, his uniform seemed moulded to him. Five o’clock, almost to the minute, and his shift had ended.

He reached the car park at the far side of the concourse, eased himself into his Skoda, settled and fired the engine. He had no need to glance back at the checkpoint because he knew precisely how it was functioning, understood all the predetermined clockwork motions which kept it running as it had run twenty-four hours a day for twenty-eight years. It ticked at a slow, even, careful pace to regulations of great exactitude. He’d handed control to his deputy, Major Simon, a competent, reliable man, and as he drove away his mind was at peace. Another day had ticked by.

The checkpoint lay broad and deep, some 50 metres by 50, hewn out of a city centre and constructed in a clearing among ordinary streets. For the tourist who chanced upon it for the first time, the impression remained invariably the same: profound incomprehension that an armed encampment could be a few footsteps beyond shops and a corner café. At that first glance it all seemed bewildering – the wall, the watchtowers, the death strip – and only when you came to know it did the geography and the geometry make sense. The checkpoint was at the precise point where East and West met.

To Moll it was known as the crossing on Friedrichstrasse, the street it straddled. To most of the rest of the world it had another name altogether, although quite why the tourist would probably have been unable to say.

A generation before, the US Army decided that checkpoints should be designated in alphabetical order. To travel across East Germany one went through Alpha and Bravo, and now here was the third. The name had a simplicity, a resonance and an alliteration which made it and its connotation recognisable on every continent.

It was called Checkpoint Charlie.

The office Commander Moll left was on the second floor of a pastel-shaded building, and through a square, squat window he could survey the expanse of the checkpoint, his checkpoint, as it faced the West: successively the Customs offices under a vast roof covering the centre of the concourse; a plain area beyond that, then three watchtowers, then the wall itself, white, 12 feet high and of vertical slabs so smooth that they offered no grip to a hand. The wall flowed along the extremity of the checkpoint to the left and right like arms, flowed on mile after mile, making an encirclement so that it locked the Western half of the city in a military embrace.

The arms of the wall folded into the checkpoint and, lower here – only shoulder high – ran across in front of the watchtowers. Two gaps had been left in it like mouths, a narrow one for pedestrians, a broader one for vehicles. The gaps allowed the old road – Friedrichstrasse – to come through the checkpoint: same road, same width, same name but the different ends of it completely separated.

Even these fortifications had been tightened a month before by the erection of a hip-high forward barricade – three tiers of concrete laid horizontally and wire mesh fencing secured to the top – although it, too, had the two mouths for pedestrians and vehicles.

Daily, Moll controlled this geometry of division, and the leader of his country had, only months before, proclaimed proudly that – no matter how many people condemned it as primitive and inhuman – the division would endure for another hundred years, maybe more.

As Moll drove the small car to his apartment in the suburbs he was not only at peace, he was a man of certainties in a country of certainties. When he reached the apartment, while his wife Inge cooked the evening meal, he’d watch television.

And did.

And the world moved.

It was 9 November 1989.

ONE

Fault Line

The construction workers of our capital are for the most part busy building apartment houses, and their working capacities are fully employed to that end. Nobody intends to put up a wall.

Walter Ulbricht, June 1961

Looking back on it, the mixture of madness and dreams seems logical, with each step leading inexorably to the next but, even so, dividing a major European city by a wall and for twenty-eight years killing anyone who tried to cross it without the right papers still stretches credulity and probably always will; but this is what happened to Berlin and this is what happened to ordinary human beings who lived and died with it.

The credulity is stretched even further because the division wasn’t a neat thing: not Paris split either side of the Champs-Élysées, not London camped on either bank of the Thames, not New York riven into East and West of the Avenue of the Americas to make two separate, sovereign countries who hated each other. No: Berlin was bisected along ancient, interwoven, interlocking district boundaries so that the division zigged and zagged through sixty-two major roads, over tram tracks, round a church and through its cemetery, across the frontage of a railway station and, stretching the credulity to its absolute limit, clean through the middle of one house. Each day an estimated 500,000 people had circulated quite normally through what would become the two hostile, alien lands. To take a random year, every day in 1958 some 74,645 bus, tram and underground tickets were sold in the West to people from the East, and that didn’t include the extensive overground rail network. Some 12,000 Eastern children went to school in the West.

The interlocking of the wall as it zigzagged across the belly of the city cutting main streets.

There was a street called Bernauer Strasse where the apartments stood in the East but the road in the West so that, by opening their front doors, residents stepped from one side to the other. There had been the subway network (U-Bahn), a spider’s web, serving the whole city, and the overground train network (S-Bahn) fulfilling exactly the same function. Both were cut by the wall but still overlapped. There had been the sewage system, and electricity, and telephones, and postal districts as common to both sides as they would be in a capital city united since (depending on which date seems conclusive to which historian) at least 1230. There had been waste disposal and burying the dead and walking in the woods on a Sunday afternoon.

No city had ever been subjected to anything like this: a son being refused permission to attend his mother’s funeral because he happened to live on the wrong side of the street.

Nor was that all. The dividing line represented the exact point where the two dominant political and financial systems of the twentieth century, each the opposite of the other, met. At Check-point Charlie in 1961 a jolly East German Border Guard called Hagen Koch had been given a bucket of white paint and a brush and told to paint a line across the road. It was, maybe, 6 inches wide but it held apart the equivalent of two tectonic plates: precisely this side was where the power of the United States and its allies ended, precisely that where it ended for the Soviet Union and its allies. That both were immensely armed with nuclear weapons, and that escalation towards their use could well begin with some trivial incident somewhere like here, made Hagen Koch’s line a defining place. For three decades people came to gaze at it and what lay around it, and were frightened. They were not wrong.

What logic, what inescapable steps, led to this – both the beginning of it in 1961 and the end of it in 1989? The journey to the answer is itself tortuous and improbable but I am persuaded that without undertaking it – even short-stepping it, as we shall be – you cannot understand why the watchtowers went up or, those twenty-eight years later, why you could have owned one provided only you could take it away and give it a good home.

This book moves in two dimensions, background and foreground. The background is the story of the wall itself and the foreground is what it did to ordinary people. To understand that properly you need the context and the logic. Here it is.

When the war in Europe ended, at 2.41 a.m. on 7 May 1945, central Berlin resembled a moonscape, and that’s as good a place as any to set out on the journey. There’s a phrase which lingers down the years like an echo of the wrath which had been visited upon the city, Year Zero, as if, now that everything had been destroyed, the trek back to civilisation must begin from here. Few Berliners thought like that yet, because the future meant surviving until tomorrow.

The bombing by the Royal Air Force and the U.S. Army Air Force broke Berlin – not the spirit of the people but most of the infrastructure and a high percentage of the buildings. Statistics are useless to convey the scale. Imagine, instead, gazing down on an area of 2 or 3 square miles and every building there like a blackened, hollowed, broken tooth. Now imagine what that looked like from ground level.

The Soviet armies reached the city in the spring of 1945 and, fighting street by street, conquered whatever resistance remained. There are mute echoes of that still in the East, where the old stone buildings bear the scattered pockmarks of gunfire.

This Prussian city of broad avenues and heavy architecture, cathedrals and churches, embassies and opera houses, hospitals and universities, pavement cafés and naughty nightclubs – this widowed place – had been home to 4 million confident, cheeky people who’d walked the walk and talked the talk of a capital city; and now ate horsemeat if they could find it.

There’s another phrase which lingers, Alles für 10 Zigaretten. It was the name of a stage review but it captured the plight of what remained of the 4 million: ‘Everything for 10 cigarettes’. Money – the Reichsmark – had no value and the currency passed to cigarettes.

Hitler never liked Berlin but, from taking power in 1933, ruled from the Chancellery, a Prussian building – heavy and classical – in the city centre.1 Dictators and diplomats came to its courtyard and walked down its marble gallery to the intimidating office where Hitler would inform them what he had decided for the world. The Chancellery was a partial ruin now: not a broken tooth but a badly beaten face. Its landscaped gardens, where his body had been burnt on the afternoon of 30 April, were cratered and grotesquely strewn with debris like a mini-moonscape.

Now the Soviets were here in their baggy uniforms, and the absolute power had passed to them. Soon enough they’d bring the exiled German communists back from Mother Russia and exercise the absolute power through them.

Major-General Wilhelm Mohnke, who’d commanded the government area, would remember2 after his capture being driven out of the city and ‘coming towards us column after column, endlessly, were the Red Army support units. I say columns, but they resembled more a cavalcade scene from a Russian film. Asia on this day was moving into the middle of Europe, a strange and exotic panorama. There were countless Panya wagons, drawn by horse or pony, with singing soldiers perched high on bales of straw.’ He added: ‘Finally came the Tross or quartermaster elements. These resembled units right out of the Thirty Years War [between Catholics and Protestants at the beginning of the seventeenth century]. All of those various wagons and carts were now loaded and overloaded with miscellaneous cumbersome booty – bureaux, and poster beds, sinks and toilets, barrels, umbrellas, quilts, rugs, bicycles, ladders. There were live chickens, ducks, and geese in cages.’

On the first days after the surrender, many soldiers in Berlin sampled the victors’ spoils and no woman was safe. Four decades later, a sophisticated lady summed this up in a phrase: ‘And the Russians had their fun.’ She looked away when she said it. A shiver of fear had run through Berlin, and nobody knows for how many women – young, old – it was justified; but a lot.

The Germans had fought a barbaric war in the East and now the barbarism had come back to them.

The German communist leader was called Walter Ulbricht, a dour Saxon with a Lenin goatee beard who’d spent the war in Moscow. Several of his comrades had disappeared in the night as Stalin carried out mini-purges but he had survived by unquestioning loyalty and tacking in the wind. One of the men who would accompany Ulbricht, Wolfgang Leonhard, has described it graphically:3 ‘At six o’clock in the morning of 30th April, 1945, a bus stopped in a little side street off Gorky Street, in front of the side entrance of the Hotel Lux. It was to take the ten members of the Ulbricht Group to the airport. We climbed aboard in silence.’ They were driven to Moscow airport and flown to Germany in an American Douglas aeroplane.

On the drive into Berlin ‘the scene was like a picture of hell – flaming ruins and starving people shambling about in tattered clothing; dazed German soldiers who seemed to have lost all idea of what was going on; Red Army soldiers singing exultantly, and often drunk’. The Berliners, waiting in long queues to get water from pumps, looked ‘terribly tired, hungry, tense and demoralised’.

Ulbricht, by nature a bureaucrat and organiser, set about creating an administration, and it would include non-communists to make it seem fully representative. He told Leonhard: ‘It’s quite clear – it’s got to look democratic, but we must have everything in our control.’

The communism which the Ulbricht group brought was based exactly on the Soviet model and, with Stalin watching in all his suspicion and malevolence, would not deviate from that regardless of whatever happened. Leonhard put it this way. ‘When he [Ulbricht] came to laying down the current political line, he did it in a tone which permitted no contradictions.’

The Soviet model which Ulbricht brought was already completed in every fundamental, because Stalin had done that through the 1920s and 1930s. It controlled everything. Built onto that was a further factor. No East European communist government came to power with the legitimacy of winning free elections, and each was pathologically suspicious of its own citizens. The logic of this, too, would play itself out.

Germany was no stranger to communism: at one point before Hitler seized power the Communist Party had 100 seats in the Reichstag. Many working-class Berlin districts remained solidly communist all the way to Ulbricht arriving. They believed that communism was a scientific path to peace, prosperity and justice for all and represented the only sane future. They had experienced market economics and had their life savings destroyed in the financial crash of 1929 (when inflation became so intense that diners paid for their meals in restaurants course by course because the price was rising as they ate). They had experienced democracy and it had brought them Hitler. Communism looked very attractive as the women of Berlin formed chains and began to clear the mountains of rubble by passing bricks from hand to hand, and the trek back to civilisation began.

Germany was carved into four Zones: Soviet, American, British and French; and, mirroring that, Berlin was carved into four Sectors. The Soviet Union took the east of the city (and its 1 million inhabitants), the Americans, British and French fashioning their Sectors out of the west (and its 2.2 million). In retrospect, and even knowing where the logic would go, it is extremely difficult to imagine how such an arrangement could have endured untroubled, because Berlin lay 130 kilometres inside the Soviet Zone. Air corridors were formally agreed but land links were not. The autobahn from West Germany to West Berlin stretched like an umbilical cord and Stalin could sever it at any moment he wished.

The Americans, British and French should have taken over their Sectors as soon as the war ended but the Soviets stalled them and it didn’t happen until 4 July 1945. A Kommandatura was set up by the four occupying powers and the official statement said ‘the administration of the “Greater Berlin” area will be directed by an Inter-Allied Governing Authority … and will consist of four Commandants, each of whom will serve in rotation as Chief Commandant. They will be assisted by a technical staff which will supervise and control the activities of the local German organs [organisations].’

The division of Germany immediately after the war.

The population had other concerns. A 10-year-old called Peter Schultz, who would go on to become a distinguished radio reporter, lived with an uncle.4 ‘I remember destroyed houses and no traffic at all except the military. I remember a jeep with a very big black American sergeant and he lifted me onto it and he gave me American-Canadian white bread. This is all I can remember about West Berlin in 1945. It was important that I got white bread: American soldiers lived downstairs and they gave me a lot of bread, for me and for the whole family. So we had bread and – this was the most important thing – white bread. I will never forget that. I can still taste it.’

In April 1946 the Communist Party merged with the Social Democrats and became the SED, which would govern East Germany throughout its life, but there were elections that autumn and the SED did badly against the other surviving parties. In Greater Berlin they finished third with 19.8 per cent of the vote and, from this moment on, would never allow another free election in the area under their jurisdiction. There would be further elections, however, on 18 March – 1990.

In retrospect, the Berlin Agreement carried too many anomalies and too many practical difficulties, heightened when the political differences between the Soviet Union and the Allies reasserted themselves as the warmth of shared purpose – defeating Hitler – iced over. That Berlin was an island deep inside the Soviet Sector made it a nerve centre between what would become NATO in the west and the Warsaw Pact in the east.

R.J. Crampton sums it up neatly:

By 1947 the British and American Zones had separated almost entirely from the Soviet and in March of that year the division of Europe into two hostile blocs became much more rapidly focused. The communists left the governing coalitions of France and Italy, the Truman doctrine warned against communist attempts to expand into Greece, and in the summer the Soviets insisted that the east European states should not take Marshall Aid. In May 1948 the new currency introduced into the three western zones of Germany provoked the Soviet blockade of Berlin and the Berlin airlift.5

To pass across this terrain citing the steps is all too tempting, but it misses the human element entirely. A British Lieutenant-Colonel, W. Byford-Jones, visited the city in 1947 and wrote:

Epidemics were rampant. The water supply was polluted – there were 521 major breaks in pipes of over 21 inches in the British Sector alone, and 80 per cent of the sewage was not reaching the sewage works. All but one of the 44 hospitals in the British Sector were badly damaged, and the 5,817 beds available were all filled, with long waiting lists. There were no medical supplies, not even anaesthetics, heart stimulants, or sulphonamides. Food was poor and at starvation level… .6

Bodo Radtke, a Berliner who was to become a leading East German journalist, says that ‘it wasn’t until 1948 that you felt things were getting back to normal. Every day you saw or heard something: one day, two U-Bahn stations are open again, very good, then three stations, then the bridge over the river Spree is open, oh very good.’7

On 20 March 1948, the Soviet delegates walked out of the Allied Control Council and never went back. They were unhappy at how Marshall Aid was affecting Soviet influence throughout Germany and, in an effort to force the Allies from West Berlin, Stalin threatened to sever the umbilical cord: from 1 April road, rail and canal traffic was hindered crossing the Soviet Zone to West Berlin. On 18 June, to Stalin’s fury, the west replaced the worthless Reichsmark with the new Deutschmark. Almost immediately it brought an end to the black markets and stimulated industry.

The British and principally the American air forces were able to sustain West Berlin by an astonishing airlift which lasted until May 1949. The Allied pilots, some of whom had been bombing the city barely four years earlier, were now keeping it alive. Enemies were becoming friends.

From Moscow, the perspective was very different. The Soviet Union had been invaded by Hitler in 1941 and almost torn apart by cruelty on a scale unimaginable. It may be that 20 million people died in the Soviet Union: Stalin, and all his successors up to Mikhail Gorbachev, regarded their primary duty as making sure that this never happened again. Stalin constructed a buffer zone of states – Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Poland – between the motherland and Germany; and would go further.

That same May in 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), embracing the American, British and French Zones, was born, but the Four Power status of Berlin remained unaltered. In October, the Soviet Zone became the German Democratic Republic (GDR), so that now two German states, both insisting they were sovereign, faced each other. The GDR government, however, claimed that East Berlin was their capital and called it simply Berlin. To them, West Berlin was Berlin (West) or variations of that, a severed limb at first then eventually left blank on their maps: a dead limb.

From Moscow, the Deutschmark, Marshall Aid and possible FRG rearmament represented great danger. Compounding that, Stalin demanded reparations from the Germans and made the East pay them. He stripped his zone of perhaps 26 per cent of its industry, dismantling it and shipping it to the Soviet Union. In May and June 1945, about 460 Berlin enterprises were ‘completely dismantled and transferred’.8 (Reparations, worth a total of 34.7 billion marks at 1944 prices were paid until 1953. It was a crippling disadvantage to the East just when the FRG’s economy was racing.)

The postwar misery of Berlin could be expressed by many witnesses. One of them, Jacqueline Burkhardt, came to the city ‘in 1949. I was born in Düsseldorf where my mother came from but my father was from Berlin. In my grandfather’s will he left my father a big old apartment house in Schöneberg and we came to live in it. I was nine. Berlin was totally flat. I saw absolutely nothing here. It was total devastation, absolutely down. There were no cars, only military vehicles. Berlin had nothing to sell. There was nothing to eat. I was very small and always hungry – you couldn’t buy food. I remember in the house was an old woman who had a ration card which got her extra rations and extra bread. For many weeks I ate the crust of the bread because this old woman had bad teeth and couldn’t eat it. I lived on that and water. It was a horrible time. Then German marks were introduced and it was a chance to start anew.’

A flow of refugees began from East to West, some political and some economic. (For an explanation of the use of capital letters for East and West, please see the introduction to the Notes at the end of the book.) The total ran at over 2,000 a week in 1949, rising to 4,000 in 1950, dropping slightly in 1951 and 1952 then reaching 6,000 in 1953, when Stalin died and workers in East Berlin rose up over an increase in the work norms. That ‘insurrection’ had to be put down by Soviet tanks and for a moment the GDR’s survival hung in the balance. It made Ulbricht’s government even more pathologically suspicious of its own citizens.

By the time Nikita Khrushchev came to power the refugee flow had become self-generating. Professional, educated, trained people – the builders of the future – were leaving and their absence made conditions worse, and the flow increased. The East looked, and was, threadbare, the West looked, and was, increasingly affluent. Berlin (West) beckoned magically from the far end of the street, across the park, a stop on the S-Bahn or U-Bahn. In Bernauer Strasse, you just opened your front door.

Because the city was under Four Power control, and open, whatever the GDR said, East Germans could make their way to the refugee centre in Marienfelde, a southern suburb of West Berlin relatively unhindered. From there they were flown to the FRG. And they kept on coming: 5,000 a week through 1955, 1956 and 1957. Despite that, Bodo Radtke says, ‘this was the happiest time. You could see construction everywhere, apartment blocks going up for people to live in.’

The act of having fled remained sensitive for decades afterwards. The story of a man who would only describe himself as Mateus (‘that should be enough’) might be seen as typical.9 His father had worked in the southern GDR town of Carl Zeiss Jena and ‘in 1955 the family decided to move to the West. He took the chance of a congress in the West to stay there, and he organised a new life. My mother started to sell what could be sold discreetly, and sending parcels to the West. Then in 1956 we went over, my mother, my sister and I. My sister was five years older than me – I was seven. Mother did not explain to me what was happening but probably my sister knew. It was better that I didn’t know, because my mother was afraid I’d start talking if I was asked questions about where we were going. We first travelled to my grandparents just north of Jena and from there to Berlin by train with two suitcases. She left these suitcases with relatives in East Berlin.

‘I can’t remember the crossing point. It seemed a sort of open border with guards who were on patrol and who controlled the passports of the people trying to go West. We simply walked across – people were moving across. My mother later told me the story: just before we crossed she slapped me, I started crying like hell and the Border Guard was pretty annoyed about this kid making all the noise. “Get him out of here!” So that went OK. She dropped us at American friends who had contact with my father and went back to get the suitcases. We learned later that she was arrested. We waited for two days for her and that was terrifying. My sister fully understood what had happened and that we might not see our mother again.

‘She was in jail for the two days but then they had to release her because there was nothing they could actually do. They didn’t have anything against her. Finally she made it but without the suitcases and the three of us flew out to Frankfurt on an old American military machine with metal seats like bath tubs. We avoided going into a refugee camp there because my father had arranged everything.’

The absurdities and anomalies of the future were largely unforeseen, but not everywhere. A young man called Kurt Behrendt,10 just married in September 1957, needed an apartment. There were some in a scenic hamlet called Steinstücken, in the south of West Berlin not far from Potsdam and bordering Babelsberg, which had been the centre of German film-making before the war and was now in the East. He didn’t know Steinstücken, he didn’t know Babelsberg and he didn’t much mind because an apartment was an apartment. ‘I came on the day the Soviets sent up the first satellite: 4 October 1957.’

Although older residents naturally had family and friends in Babelsberg, Behrendt found himself living in what was now an enclave. ‘It was difficult because, since the political division of Berlin in 1945, they argued whether it belonged to the East or the West. Then they recognised that it belonged to the West but one of the difficulties was getting to it. You came over a bridge which, prior to 1945, belonged to Potsdam but after 1945 belonged to the GDR. So you had to come through the GDR and only residents were allowed to do that. There wasn’t even a street, only a path through the forest. You could get through by car but it was so narrow that if two cars met one had to pull onto the side. The school was in Wannsee [near a lake] and the children went along this path to the bridge and took the bus there. A little later the community had a school bus and my wife Helga drove it.’

The absurdities and anomalies would revisit Behrendt, becoming more serious each time.

In 1958 the refugees came at 4,000 a week, and in 1959 at 3,000. The overall total in 1959 stood at 143,917, of which 90,862 had passed through West Berlin and the rest from the GDR to the FRG. In 1960 the refugees came at 4,000 a week with a record 16,500 in May. The overall total stood at 199,188, of which 152,291 had passed through West Berlin.

This was the equivalent of losing a town a year, and no small country could survive it for long. Ulbricht saw this as clearly as everybody else and exhorted Khrushchev to staunch the flow. Khrushchev made several attempts to force the Allies out of West Berlin, threatening to sign a unilateral treaty with the East German government – but that would mean unilaterally ending the Four Power Agreement, and unilateralism was extremely problematical in a nervy, nuclear era.

And still the refugees came. After processing, most sat huddled shoulder to shoulder on mattresses in the centre at Marienfelde. Its interior was wide like an aircraft hanger, the children cradling their heads in their arms, already asleep. The women gazed ahead unseeing. Here and there a hand comforted a child, smoothing its hair in timeless rippling motions of warmth and reassurance. That masked anxiety. The Eastern Railway Police and Peoples’ Police searched West-bound trains heavily now. Anyone with luggage might be hauled off, and any obvious family travelling together – father, mother, children – might be hauled off, too.

Friedrichstrasse station,11 which itself would become an absurdity and an anomaly, was the last stop before the West. Twelve policemen tried to check all the compartments as each train stopped but even on Saturdays, when the trains were more lightly filled, they struggled to check them all. Getting across became a matter of luck, chance, ill-luck, averting your gaze from a policeman’s glance, keeping your nerve, looking innocent, literally sitting tight.

Some families took precautions and split up, the father going with a child one day, the mother following the next, perhaps alone – less suggestive like that – or perhaps with another child. Some left their suitcases behind, as the mother of Mateus had done, and went back to retrieve them only when the children were safely delivered to the West.

In January 1961 John Kennedy was sworn in as President of the USA and six months later he met Khrushchev in Vienna. In the background and far away, the mute, anxious, exhausted refugees still flowed in at 4,000 a week and Khrushchev’s aides were joking that ‘soon there will be nobody left in the GDR except for Ulbricht and his mistress’.12 In addition, the Soviets were concerned that their economic assistance to the GDR would ‘end up in the pockets’ of the Westerners because the Deutschmark had so much more purchasing power than the GDR’s Ostmark.

At Vienna, Khrushchev went unilateral. Unless the Allies agreed to a German peace treaty within six months he would sign a treaty with the GDR ‘normalising’ the situation in Berlin. The Allied troops would have to go and West Berlin would become a free city with control of all access, including the air corridors, passing to the GDR.

‘Mr. Khrushchev left no doubt as to his “irrevocable” determination to conclude a separate treaty with the GDR, with all attendant consequences for the west as already threatened. President Kennedy said the United States would regard any violation of vital rights of access and any encroachment on West Berlin as a breach of US rights and interests.’13

Frank Cash, who worked for the US State Department’s Berlin Task Force, says14:

The bigger picture of interlocking Berlin: some of the districts on both sides of the wall and three Eastern towns, plus the Western enclave of Steinstücken.

I think Ulbricht pushed Khrushchev and Ulbricht was right because they were haemorrhaging with the refugee flow: all of these people who were coming out were those that he needed most, the young, active, bright engineers and professional people and he really had to stop it in some way. I also had the feeling, having attended the Vienna summit, that Kennedy really was pleading with Khrushchev to help him find a way out. I think that that was Khrushchev’s assessment of Kennedy and, OK, he – Khrushchev – could go ahead with a wall.

There’s another thing that emerged from the Vienna meeting. Berlin came up [on the agenda] and the White House made much of the fact that the Allied response to Khrushchev’s demands took 45 days to appear. What actually happened – and I know this very well – was: McGeorge Bundy [Kennedy’s National Security Adviser] asked if we could prepare a policy and we did but when we rang the White House they said ‘what document?’ They’d lost it, so ten of the 45 days were really due to the White House. I’m not sure if Khrushchev took the delay as a sign of weakness.

We also looked back to other Soviet demands and our responses, and this was not an undue amount of time. All of Khrushchev’s demands were a rehash of earlier demands and there was nothing new in it so we could go back to previous responses which had been agreed within the US government and say ‘well, here’s this point and here’s our response’. But you want to get an answer out quickly. If you’ve got responses which have been previously cleared by the US government, the British and French, then you’re going to have very little problem getting it cleared again and that’s what we did.

I think the comment to our response from the White House, when it finally arrived, contained only one new idea – submission to the International Court of Justice of Berlin’s rights – and from that point the answer as it went out was essentially the one we had submitted three or four days after we got the original request.

Did Khrushchev read much into this delay? Nobody knows.

From Sunday 4 June 1961, when the Vienna Summit broke up in bitter disarray, the logic became more insistent and the steps were closer, were taken more quickly and were moving towards an abyss. Even now, in retrospect, when the consequences of the logic should be clear, it is all but impossible to evaluate which of these steps increased the sense of crisis more. They have a cumulative feel to them, a sense of something very powerful in play.

When Kennedy returned to the United States two days after Vienna he made a television and radio address: ‘Our most serious discussions dealt with Germany and Berlin. I made it clear to Mr. Khrushchev that the security of Western Europe, and with it our own security, is intimately interlinked with our presence in and our rights of access to Berlin, that these rights are based on legal foundation and not on sufferance, and that we are determined to maintain these rights at all cost and thus to stand by our commitments to the people of West Berlin and to guarantee their right to determine their own future.’

The flow of refugees rose to over 4,000 that first week after Vienna.

The Secretary of State, Dean Rusk, said15 that ‘an attack on West Berlin would have moved rather quickly to a nuclear situation. Yes, I really think that. It was part of the Berlin planning all along, particularly since Khrushchev had given the president an ultimatum on Berlin at Vienna. So the British, the French and ourselves as well as the West Germans put our heads together to work out contingency plans and they were based on a gradual upping of the ante depending on the East German and Russian reaction. Kennedy had explained to Khrushchev that we could not accept an attack on West Berlin and, as a matter of fact, at one point during the conference Khrushchev said he was going to do this about Berlin and do that about Berlin and Kennedy said “there will be war. It’s going to be a very cold winter.” It was in the forefront of my mind that there was nothing we ought to try and do about East Berlin but any infringement into West Berlin would have set in motion the contingency plans.’

After Vienna, Khrushchev accepted Ulbricht’s proposal that the Warsaw Pact countries should meet in Moscow as soon as practical.

The flow rose slightly above 4,000 in the second week.

On Saturday 10 June16 Yuli Kvitsinsky, an attaché in the Soviet Embassy in East Berlin, ‘learned in a meeting with E. Huttner of the East German Foreign Ministry’s department on the Soviet Union that many in the East German leadership felt that it was “high time, at last, to sign a peace treaty and on that basis resolve the West Berlin issue. This measure is connected with a certain risk, but there is even more risk in the further delay of the resolution of the issue, since any delay assists the growth of militarism in West Germany which increases the danger of a world war. Thus, the danger of conflict in connection with the conclusion of a treaty with the GDR is balanced by the other danger. In this connection … Comrade P. Florin, chairman of the SED CC International Relations Department, said that further dragging out the signing of a peace is a crime.” It was also assumed that at some point “the sectoral border in Berlin would be closed.”’

When Hope M. Harrison [see note 15] asked Kvitsinsky about this in an interview, he said: ‘There was not then on our part a real readiness to conclude a [general overall] peace treaty with Germany. We were not impatient. But the GDR was impatient and in a weaker situation and Ulbricht used strong propaganda for a peace treaty.’

On Monday 15 June, Ulbricht called a press conference – itself highly unusual – at the House of Ministries (in another life it had been the headquarters of Hermann Goering’s Luftwaffe) and, during it, restated the position outlined by Khrushchev’s ultimatum. Annamarie Doherr, a journalist of the western Frankfurter Rundschau, asked ‘Does the formation of a Free City in your opinion mean that the state boundary will be erected at the Brandenburg Gate?’

‘I understand by your question,’ Ulbricht replied, ‘that there are men in West Germany who wish that we [would] mobilise the construction workers of the GDR in order to build a wall. I don’t know of any such intention. The construction workers of our country are principally occupied with home building and their strength is completely consumed by this task. Nobody has the intention of building a wall.’

Why Ulbricht said this is not known. One theory suggests that he was simply telling the truth as he perceived it at the time, another that he must have understood the effect his words would carry within the GDR, particularly when the press conference was extensively reported in Eastern newspapers and on Eastern television. Ordinary people, accustomed to reading the inner meanings of doublespeak, would assume he was going to build a wall – provoking a rush to Marienfelde. That would force Khrushchev’s hand because Khrushchev could not afford to let the GDR die.

On Wednesday 28 June, a senior GDR International Department official returned from Moscow and told Ulbricht that the Soviet Presidium would discuss the request for the Warsaw Pact meeting on the following day. The steps within the logic were very short now.

In the third and fourth weeks of June the flow of refugees continued at over 4,000 and by the month’s end, only halfway through the year, the overall total had reached 103,159, with 49.6 per cent under the age of 25. The future itself was flowing away.

Former Soviet diplomat Yuli Kvitsinsky wrote in his memoirs17 at the end of June or the beginning of July that Ulbricht invited him and Soviet Ambassador Mikhail Pervukhin to his country house. There Ulbricht told Pervukhin to inform Khrushchev that ‘if the present situation of open borders remains, collapse is inevitable’ and that ‘he refuses all responsibility for what would then happen. He could not guarantee that he could keep the situation under control this time [the haunting of the 1953 uprising].’ Kvitsinsky is not more specific about when this took place but notes that after it nothing seemed to change.

Then, according to Hope M. Harrison, a political scientist who has researched this period exhaustively, ‘one day’ Pervukhin told Kvitsinsky to find Ulbricht immediately and bring him to Pervukhin. Pervukhin informed Ulbricht that Khrushchev had agreed to close the border and that Ulbricht should begin preparations in great secrecy. The operation was to be executed very quickly so as to be a complete surprise to the West. ‘Ulbricht immediately went into great detail about what must be done. He said that the only way to close the entire border quickly was to use barbed wire and fencing. He also said that the U-Bahn and S-Bahn to West Berlin must be stopped and that a glass wall should be put up at the main Friedrichstrasse train station so that East Berliners using the metro could not change over to the train to West Berlin. Kvitsinsky noticed that Pervukhin was quite surprised at how much Ulbricht had already thought through these details.’

On Monday 3 July, Ulbricht spoke to the 13th plenum of the SED. He said a peace treaty was imminent and assured the comrades that Khrushchev would act before the FRG had nuclear weapons. He outlined how action would be taken in Berlin against the so-called border-crossers: people who lived in one sector but profited by working in the other.

Next day, Pervukhin submitted a detailed sixteen-page report to Andrei Gromyko, the Soviet Union’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, with his analysis of what signing a peace treaty with the GDR would bring. He wrote of ‘the establishment of a regime over the movement of population’ between the two halves of Berlin and felt ‘it would be better at first not to close the border, since this would be difficult technically and politically’.18

The total that week was 4,000 again.

On Friday 7 July, Erich Mielke – head of the GDR secret service (the Stasi) – told his senior officials he was ordering immediate preparations so that ‘operative measures can be carried out at a certain time according to a united plan’ and demanded ‘a strengthening of security of the western state border and ring around Berlin’.19

On Saturday 8 July, Khrushchev spoke at a military academy and said the demobilisation of Soviet armed forces had been halted. That second week the flow rose to 8,000.

On Saturday 15 July, an unsigned report to Ulbricht spoke of how, after the writer of the report had had conversations in Moscow, ‘we should especially expect to deal with questions about West Berlin’ at the Warsaw Pact meeting, now scheduled from 3 to 5 August.

Lutz Stolz and his fiancée Ute lived in East Berlin but went to visit Ute’s aunt in the Black Forest. ‘At this time you had to apply for an interzonal passport so I went to the authorities and applied for Lutz and myself,’ Ute says. ‘First, they only gave me a passport and wouldn’t allow him to go. I applied a second time and, although I really don’t know why, I succeeded. I remember the day well. I went along the little side street jumping up and down the kerb with joy waving the passport in my hand and saying “we can both go, we can both go”.

‘We went by train to Stuttgart where our relatives were waiting for us and they took us to their little village, Rohrdorf, a very romantic place in the mountains.’ This happy, almost idyllic, time would haunt the couple. ‘We had our work, our parents, the houses of our family all in the GDR, and the houses, even in the GDR, were worth something. We can never say whether we’d have stayed if we’d known. My parents-in-law could have sold up in the GDR and come as well, everything would have been done fast – but how could we know then? Would we really have stayed in the little village in the mountains, leaving behind the security of our family? Would we really have dared? When we were leaving we told my aunt and uncle that we’d try and visit them again the following year. It never occurred to us that …’

On Monday 17 July, the three Western Allies rejected Khrushchev’s ultimatum to change the status of Berlin. That third week the flow rose to 9,000.

On Saturday 22 July, a secret telegram from the State Department in Washington went out to the London, Paris and Moscow Embassies as well as the US Embassy in Bonn and to Berlin. It was arranged in nine numbered paragraphs, phrased in a sort of cabalese, and it explored possibilities. It said that ‘if refugee flood continues’ the GDR could ‘tighten controls over travel from Soviet Zone to East Berlin or by severely restricting travel from East to West Berlin’, and added: ‘We believe Soviets watching situation even more closely than we, since they are sitting on top volcano. Continued refugee flood could … tip balance towards restrictive measures.’

The telegram also contained a great truth: ‘If GDR tightens travel controls between Soviet Zone and West Berlin there is not much US could do, other than advertise facts. If GDR should restrict travel within Berlin, US would favour counter-measures’ – including economic.

Lutz Stolz and Ute came back from Rohrdorf. ‘When I went to the authorities to get our identity cards back – we had had to leave them before our departure – I noticed that they were smiling in a strange way when they handed them over,’ she says. ‘It was like a scornful smile on their lips as if they were thinking: these stupid people, if only they knew …’

The German Protestant Church Synod, due to be held in West Berlin from 19 to 23 July, was banned by the East Berlin chief of police.

On Tuesday 25 July, Kennedy spoke on American television. He defended the Allies’ rights in West Berlin and stressed that any unilateral action against West Berlin would mean war with the United States, but made no mention of East Berlin, a deliberate nuance, perhaps, which Khrushchev would deduce as giving him a free hand there.

On Wednesday 26 July, Ulbricht sent to Moscow a summary of the speech he would be making at the Warsaw Pact meeting there nine days later. He proposed creating a state border between East and West Berlin.

On Sunday 30 July, Senator William Fulbright, chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations, said publicly that he could not understand why the East Germans were not closing the border, because they had every right to do it. Under the Four Power Agreement, the GDR had no rights like this, of course.20 It may be, however, that Khrushchev and Ulbricht – who’d essentially spent the whole of their adult lives within totalitarianism – assumed Fulbright’s words would have been sanctioned and were code for: do what you want in your own backyard.

Certainly Richard Smyser, a junior officer in the American Berlin Mission, thinks so. Smyser, an American born in Vienna (his father was a diplomat) had spent part of his childhood – 1939–41 – in Berlin and returned in 1960 to join the Mission. Smyser says that Khrushchev and Ulbricht ‘took the Fulbright speech as the go-ahead. The Russians have told me that Ulbricht expected no military response.’21

That fourth week the flow fell slightly, to 8,000, but the total for the month reached 30,415, of which 51.4 per cent were under the age of 25. On 2 August alone the total was 1,322.

Many astute judges, particularly in the CIA and the State Department, had contemplated a division of the city as an abstract proposition and concluded that in practical terms it could not be done. At least one Stasi general, Markus Wolf – famed, fabled and feared spymaster – reached the same conclusion as he pondered dividing the East’s 1,071,775 from the West’s 2,207,984.

In the city, the halves interlocked intimately as they had for centuries and to prise them apart some sort of barrier would have to run for 28½ miles. From the north, and beginning in countryside, it would go westwards in a triangle at the first of the housing, follow a railway track with houses on both sides for 3 miles and embrace parallel railway tracks, one of them from the West but looping inside the line; then turn at a right angle into Bernauer Strasse; double back over the Western U-Bahn line beneath East Berlin, follow a narrow canal bank and bisect a bridge, run directly behind the Reichstag to the Brandenburg Gate and on to the broad expanse of Potsdamer Platz. It would then corkscrew left and bisect five streets, zigzag across seven more streets until it reached twin, curved roads with sunken gardens between them; and turn to follow the banks of the Spree to the district of Treptow, itself a maze. There the barrier would turn westward, bisecting half a dozen streets… .

To seal the GDR countryside looping round West Berlin, the barrier would have to run 22.30 miles through residential areas, 10.56 miles through industrial areas, 18.63 miles through woods, 14.90 miles through rivers, lakes and canals, and 34.15 miles along railway embankments, through fields and marshes.

Could such a thing really be done?

George Bailey, a veteran American journalist who knew Germany intimately, wrote a feature in a magazine called The Reporter in which he said that the Soviet Union and ‘its East German minions’ have ‘finally drawn the ultimate conclusion that the only way to stop the refugees is to seal off both East Berlin and the Soviet Zone by total physical security measures’. He foresaw ‘searchlight and machine gun towers, barbed wire, and police dog patrols. Technically this is feasible.’22 The feature was billed as ‘The Disappearing Satellite’ and, in Bailey’s words, ‘attracted a good deal of attention’.

One account23 says Ulbricht flew to Moscow on the last day of July and was informed by Khrushchev that the peace treaty was not going to be signed yet but he could close the border. Ulbricht wanted to close the air corridors, too, which would prevent the refugees who did reach Marienfelde from flying on to West Germany, but Khrushchev weighed up the risks and said no. Ulbricht suggested building a wall around West Berlin on EastGerman territory and Khrushchev said he would put that to the Warsaw Pact meeting. (For reasons of security, he cannot have done this in open session; rather, he sounded out various members in private.)

On Thursday 3 August, Khrushchev opened the meeting by accusing the ‘Western powers’ of receiving ‘our proposal for a peace treaty with bayonets’ and added: ‘Kennedy essentially threatened us with war if we implement measures for liquidating the occupation regime in West Berlin.’ He called for the meeting to work out detailed plans and gave the floor to Ulbricht.

In great and laboured detail, Ulbricht moved through the whole situation and made his pitch: how the peace treaty must be signed without delay and how the ‘whole socialist bloc’ must be ready to risk confrontation to protect the GDR, although he made no mention of a wall.

At some stage on 3 August,24 Khrushchev seems to have added a proviso to closing the border. Ulbricht must give an assurance that his government could deal with any civil unrest (the haunting of 1953 again). Ulbricht flew back to East Berlin on Friday 4 August and satisfied himself that such an assurance could be given. The New York Herald Tribune prepared a front-page story headed ULBRICHTSAIDTOSEEKASSENTBYKHRUSHCHEVTOCLOSEBERLINBORDER.