Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

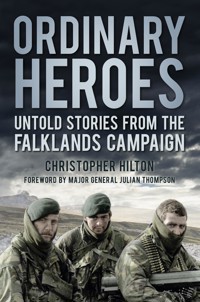

In 1982, 8,000 miles from home, in a harsh environment and without the newest and most sophisticated equipment, the numerically inferior British Task Force defeated the Argentinian forces occupying the Falkland Islands and recaptured this far-flung outpost of what was once an empire. It was a much-needed triumph for Margaret Thatcher's government and for Britain. Many books have been published on the Falklands War, some offering accounts from participants in it. But this is the first one only to include interviews with the ordinary seamen, marines, soldiers and airmen who achieved that victory, as well as those whose contribution is often overlooked – the merchant seaman who crewed ships taken up from trade, the NAAFI personnel who supplied the all-important treats that kept spirits up, the Hong Kong Chinese laundrymen who were aboard every warship. Published to mark the thirtieth anniversary of the conflict, this is the story of what 'Britain's last colonial war' was really like.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 405

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Front Cover Photograph: Royal Marines wait to go on patrol from Ajax Bay during the Falklands Conflict in 1982. (© Adrian Brown/Alamy)

CONTENTS

Foreword by Major General Julian Thompson, CB, OBE

Introduction

Part One

1. All at Sea

2. The Missile Man

3. The Radio Operator

4. The Marine Engineer

5. The Helicopter Expert

6. The Heavy Mover

7. The Lucky Paratrooper

8. The Unlucky Paratrooper

9. The Prisoner

10. The 29-Year-Old Teenager

11. The Islander

Part Two

12. Personal Conflicts

13. Time Travellers

14. Joking, Crying and Dying

Appendix: Men and Ships

FORWARD

BY MAJOR GENERAL JULIAN THOMPSON, CB, OBE

One of the enduring myths of the Falklands War is that of underage Argentine soldiers being committed to an unequal battle; the implication being that the British servicemen were so much older, and hence better. That is why the Argentines were defeated. It is, of course, a face-saving myth propagated to explain why they lost, and reminds one of the age-old childish gripe ‘it isn’t fair’. In fact, no Argentine soldier was conscripted before his 18th birthday, and many were well over 18 because they were not plucked off the street the moment they reached that age, but drafted in batches. So by the time an Argentine soldier was shipped to the Falklands, having completed training, he was around 18½ years old. At least one of the regiments who served in the Falklands was made up of Argentine conscripts who had had their service extended for the operation and were over 19½.

Yes, the British were better, but not because they were older – we shall return to that. The two youngest British soldiers to be killed were just 17. Several British marines and paratroopers celebrated their 17th birthday on the journey south. Every single one was a volunteer, along with the rest of his comrades.

This book is special because it consists exclusively of contributions by men who were the equivalent of private soldiers at the time – ordinary seamen, marines and the like. Not one of them was even as elevated as a lance-corporal. This is important because the popular image of the armed services is of a pyramid. At the top is the general or admiral sitting on a base consisting of myriad junior folk. In reality, one should view the armed services as a collection of inverted pyramids, each point being an individual without whom the battle would not be won: a sailor, marine or soldier. The best-laid plans and the cleverest generals and admirals are not sufficient by themselves. They need people to win the battle for them. This book contains accounts by those that did just that. They won it because they were better, not because they were British and not Argentine. They were professionals, better trained and hence better motivated. I was once asked why we won. I said there were three reasons: training, training and training.

All of the British servicemen who took part in the Falklands War were thrown in at the deep end, metaphorically speaking. There were no plans to retake the Falkland Islands in the event of an Argentine invasion. There were two reasons for this: first, the British Government, and the Foreign & Commonwealth Office in particular, believed that the Argentines were bluffing and would not invade; and second, about six months before the proverbial hit the fan the Ministry of Defence had come to the conclusion that retaking the islands was impossible. This is well documented in the British official history of the war.

When the Argentines did invade, the box marked ‘Mission Impossible’ was opened and the British armed forces were invited to see if they could prove this assumption was incorrect. The task was only possible because of the professionalism, skill and courage of the people who appear in the pages of this book, and thousands more like them.

Readers today may wonder at the differences between the conditions in which this war was fought and today’s conflicts. There were no emails or mobile telephones. Mark Hiscutt of HMS Sheffield had to write to his fiancée: ‘Not coming home. Cancel the wedding. Lots of love. Mark.’ He was not allowed to say why his ship was suddenly not going back to England from Gibraltar but steaming off 180 degrees in the other direction. He was not alone: there were thousands like him. Once deployed no-one could communicate with home other than by mail. As the Task Force approached the Falklands, mail for home was often deliberately delayed to ensure that no secrets were inadvertently betrayed – the alternative being to censor letters.

The handling of the media was poor. The news about the Sheffield being hit was on the TV well before any next of kin were informed. This was not an isolated case. Newspapers and mail arrived episodically. There was no satellite TV. Everyone down south lived in a bubble, cut off from the outside world.

If you were in a ship you might be drier and better fed than your opposite number ashore, but your end could be swift, violent and while it lasted extremely unpleasant: cut off alone in a burning compartment, or battened down below in a sinking ship, with no chance of getting out. When ships were hit, casualties were usually heavy; many dead, many with horrific burns.

A marine or soldier ashore faced cold, injuries, hunger, fatigue and broken bones caused by the unforgiving weather and terrain, all without the enemy lifting a finger. He would be invited to assault the enemy, and patrol, often at night. Having eventually arrived on his objective, he might be shelled for several days and nights, existing on short rations because his rucksack had not arrived, shivering in the cold because his sleeping bag was in his rucksack, and glad of captured Argentine blankets. The helicopters were too busy carrying ammunition. Soldiers in rear areas were subject to the attentions of the Argentine air force, and lived in holes like their fellows nearer the enemy. Napoleon knew what he was talking about when he said ‘the first quality of a soldier is fortitude in enduring fatigue and hardship: bravery but the second.’

Nobody knew when it would end. There was no tour length as in Afghanistan, Iraq or Northern Ireland. It would end when it ended.

One of the greatest remedies in time of danger and doubt is humour. The British services are renowned for their ‘black’ humour. David Buey, on being picked out of the water by HMS Alacrity after the Atlantic Conveyor was hit, asked a sailor how Tottenham Hotspur had got on in the Cup Final against Queen’s Park Rangers. ‘If I’d known you were a Tottenham fan, I would have thrown you back,’ replied the Alacrity sailor.

Some of the contributors are suffering from, or have experienced, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). This is a condition about which too little is known even today. At the time of the Falklands War, thirty years ago, a great deal less was known about it, or, more correctly, a great deal that had been learned in the Second World War and Korea had been forgotten. In the 1970s and early 1980s PTSD was popularly thought to be something that happened to Americans in Vietnam. The British forces medical services were apparently unaware of the work being done in Australia on their veterans returning from Vietnam; and, if they were, they were not interested – nothing was done. There were no arrangements in place to cope with PTSD at the time of the Falklands War. Now service people returning from a war zone are put through a period of ‘decompression’; then there was no such thing, except by chance. Those that came back in ships together with their mates on a voyage that averaged three weeks were better off than those who were evacuated by air from Montevideo, having been taken there by hospital tender from the battle area. Those that came back with strangers, and flew part of the way, to be decanted straight into the midst of their families, were more prone to PTSD. They suffered, as did their families.

Fortunately, a British psychiatrist, Surgeon Commander Morgan O’Connell, RN, who had accompanied the medical teams in SS Canberra, understood what was happening, and did something about it. He started treating Royal Navy personnel who showed symptoms of PTSD, and the Royal Navy became the first British service to recognise it as a condition and treat it. The others have now followed suit.

The war in the South Atlantic was short, but bloody. The fighting at sea and ashore had much in common with the Second World War experience. Some of the technology was different, but watching the ships in San Carlos Water repelling Argentine air attacks day after day reminded me of accounts I had read of the Royal Navy fighting it out toe-to-toe with the Luftwaffe off Crete only forty years before. Young marines and soldiers not only closed with the enemy, but endured prolonged artillery and mortar bombardments, as well as being on the receiving end of enemy air attacks – this last is something that no British service person has experienced since.

These, and much else besides, are the subject of this book: the authentic voice of the point of the pyramid.

INTRODUCTION

Every man in this book is a volunteer twice. Each volunteered to join the British services, which is what took them to the Falkland conflict with Argentina thirty years ago, and each has volunteered to describe what happened to them when they got there, with, just as important, what has happened to them since.

I want to set out the book’s framework immediately. I did not know any of these men and I did not select them. Through various organisations (which will be fully credited in a moment) the word went out that a book was in the making, it would consist almost entirely of memories, and the volunteers selected themselves by coming forward. There was a condition: none of them could have had a rank at the time of the conflict, so that even lance-corporals were excluded.

One volunteer, Paratrooper Dave Brown, had reservations about this: ‘A lot of the navy people were junior ranks. A lot of times there were lance-corporals leading section attacks at Goose Green.’ Brown felt the exclusion should be everyone above sergeant, because otherwise ‘they miss out in telling their bit’.

If this was a history of the conflict, Brown would be right. It isn’t. It is the very personal stories of ten men who were all of modest background, and who were young, who mostly left school early and were at the very lowest strata of the services. None could give any man an order, only obey the orders given to them. That is why there are no lance-corporals (and no disrespect whatever is intended).

From the obedience, the lowest – outnumbered and trapped in the unavoidable confusions of such an enterprise – won a war at a windswept, treeless, frozen place 8,000 miles from home which they had never heard of before. You can argue, and must argue, that a military victory is a tight-knit team effort, and each varied – very, very varied – component essential. In this, you cannot fail to argue that brilliant generals and brilliant technology come to depend, down all the centuries, on the quality of the men in the boots with simple weapons, what they can do and what they will do.

This book is about what they did.

The fact that they were unselected makes them representative in a bigger way: what happened to ordinary blokes.

Nationalism and chauvinism can lead straight to triumphalism. It’s easy to get there, and particularly easy with a conflict which was so precisely defined between right and wrong: Argentina invaded and occupied a British colony, full of people who’d lived there for a couple of centuries and didn’t want Argentina in any guise. If you live in Falkirk or Folkestone, imagine waking up having been ‘liberated’ by a Spanish-speaking army and you get the idea.

You will be finding very little triumphalism, but a profound sense of satisfaction at a job well done, against the odds in every sense; terrible fear and authentic bravery; great gales of gallows humour; grief etched into the sadness of ultimate sacrifice; and pity for the Argentine conscripts who, taken prisoner en masse, would be better treated by the British soldiers than their own officers. As one of the volunteers puts it, ‘in the end you looked at them and thought they were human beings just like you.’ Every volunteer came back wiser, or, as another put it, ‘I went as a 19-year-old and came back as a 29-year-old several weeks later’.

Each volunteer was interviewed on the telephone, and for a reason. At a physical meeting the writer will be unable (trust me, I know) to resist setting the scene in florid detail, describing the look and mannerisms of the interviewee, catching and reporting their gestures. I didn’t want any of that. I wanted them unadorned, revealing themselves through their words alone, not through my descriptions and interpretations. What you will be reading is exactly what came down the phone, so that you will be as close to it as I was. At strategic places, words of explanation and background have been added, but not much more.

Each interview was, by its nature, a self-contained story with its own insights; each was strong enough to demand its own chapter, and the order of the chapters is the order in which the interviews were done. Cumulatively they demonstrate what the most ordinary of British people can achieve, and if their discipline and purpose stands in direct contrast to so much ill-discipline in today’s society by people of the same age and background, isn’t that interesting?

Most of the volunteers have paid a price, although they were completely unaware of that at the time. The price was called Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, and it can devastate lives. Each volunteer has coped – or tried to cope – with it, and I offer sincerest thanks to them for their extraordinary candour in describing what they have endured. Part Two, where the PTSD is recounted, does not make happy reading, although, now that the condition is recognised, hope is threaded through. Several of the volunteers said quietly that if their words comfort others – you are not alone – or if their words point out that professional help is at hand, their descriptions will have been worthwhile.

One man has been selected, and here I must declare an interest. I worked for the Daily Express, and so did reporter Bob McGowan, who covered the war for the newspaper. McGowan co-authored his own book, Don’t Cry for Me, Sargeant-Major, with Jeremy Hands, which has been much praised since it first appeared shortly after the war – and a sequel in 1989, Try Not to Laugh, Sergeant-Major. McGowan, a razor-sharp news reporter, and Hands caught the chaotic humanity spread before them. I asked McGowan to reflect on how ordinary servicemen coped, and he has captured that with touching (and highly amusing) insights.

I offer thanks to Gordon Smith of www.naval-history.net for allowing me to quote. The website is a superb resource.

I am particularly grateful to Neil J. Kitchener of Cardiff & Vale NHS Trust Laision Psychiatry for all his help; to Jane Adams, secretary of South Atlantic Medal Association; and to Alex Bifulco, press officer of the RAF Association. I don’t need to thank the ten volunteers here. Just read on, and you’ll understand the depth of my gratitude to them all.

PART ONE

1

ALL AT SEA

It seemed a most trivial thing. On 20 December 1981 an Argentine scrap metal merchant, Constantino Davidoff, landed on South Georgia, an island lost in the cold waters of the southern Atlantic. With the South Sandwich Islands, which lay some 300 miles further on, it represented, literally and figuratively, the end of the British Empire.

South Georgia has been described as ‘breathtakingly beautiful and a sight on an early spring day not easily forgotten’. It has also been described as:

long and narrow, shaped like a huge, curved, fractured and savaged whale bone, some 170 kilometres long and varying from 2 to 40 kilometres wide. Two mountain ranges (Allardyce and Salvesen) provide its spine, rising to 2,934 metres at Mount Paget’s peak (eleven peaks exceed 2,000 metres). Huge glaciers, ice caps and snowfields cover about 75% of the island in the austral summer (November to January); in winter (July to September) a snow blanket reaches the sea. The island then drops some 4,000 metres to the sea floor.1

On a global scale, anything which happened there would be a most trivial thing.

South Georgia had no native population, but it did have a small number of residents, including staff from the British Antarctic Survey, which had scientific bases at Bird Island in the far north. The residents would see, among other things, a lot of elephant seals, fur seals and king penguins. The capital, Grytviken, was no more than a few buildings huddled between the ocean and the stark, immense Allardyce Range rising behind.

Davidoff landed without permission at Leith Harbour, a derelict whaling station 15 miles north of Grytviken. Thereby lies a tale, because he had, he would insist, tried to get permission from the British and even ‘signed a deal worth $270,000 [£180,000] with the Scottish owners’ of the station to take the scrap away.2

Word reached the British Antarctic Survey base at Grytviken, but, when they got to Leith Harbour, they found Davidoff had gone. They also found that he had left a message, in chalk, announcing that South Georgia belonged to Argentina, which had laid claim to them since 1927. Argentina had trained more covetous eyes on the Falkland Islands, which had many more inhabitants amongst the seals, penguins and particularly sheep. The Falklands, a British colony since 1833 and some 800 miles to the north-east, had always been claimed by Argentina and they even had a Spanish name, the Islas Malvinas. With South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands they formed a community composed of small, distant parts.

Two days after Davidoff’s landing, Lieutenant General Leopoldo Galtieri seized power in Argentina using that country’s traditional method of transferring power: a military coup. Davidoff’s landing still seemed a most trivial thing, in total no more than a fleeting visit by a scrap-metal dealer who scented scrap on South Georgia and left some mindless graffiti on his way out. It had, of course, nothing to do with Galtieri.

Mark Hiscutt, a 21-year-old gunner – or missile man, as they’re known – from Farnborough had joined HMS Sheffield, a Type 42 destroyer, in March, and since November had been in the Gulf. In the New Year, Sheffield would take part in Exercise SPRING TRAIN, but Hiscutt would be home by 8 May. He had to be. It was his wedding day. ‘I had a fair idea where the Falklands were, yes, I knew they weren’t north of Scotland’ – which many in the services did not know.

Brian Bilverstone, a 20-year-old radio operator on HMS Herald, an ocean survey ship, was in the Middle East on a seven-month trip. Watch duty tended to be quiet. There were four teleprinters in a bank, one permanently on, the other three on standby. One was invariably enough because the Herald rarely received more than thirty messages a day. Bilverstone would spend time listening to the teleprinter chattering away – or more likely hearing silence. He ‘didn’t have a clue’ where the Falklands were: ‘We thought it was Scotland.’

On 9 January 1982 the British Ambassador in the Argentine capital, Buenos Aires, lodged a formal protest about Davidoff’s landing. Three days later the Argentinian Joint Armed Forces Committee began plans to invade the Falklands. Galtieri, now ruling through a junta, inherited a country destroyed by financial problems and traumatised by fighting a ‘dirty’ internal war against all manner of perceived opponents. He was not popular, but a solution lay to hand: the Islas Malvinas. Their value was entirely symbolic, but, to the destroyed and traumatised, hugely symbolic. Just as importantly, they were defended by only a symbolic force of sixty-eight Royal Marines and HMS Endurance, an Antarctic patrol vessel which ‘maintained Britain’s presence around the Falkland Islands and supported the British Antarctic Survey’.3 The Endurance was to be decommissioned as an economic measure which British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher announced on 9 February. Galtieri could be forgiven for reading this as a withdrawal, opening the islands to him.

Steve Wilkinson, a 21-year-old marine engineer from Chesterfield, was on HMS Exeter, another Type 42 destroyer, halfway through a three-month tour of the West Indies doing guard duty. ‘It was very nice and pleasant. The locals were very friendly and there were were quite a few barbeques and parties to be had.’ He ‘didn’t know where the Falklands were. It was very sketchy because it’s like the Shetlands and the Orkneys. It’s just another bunch of islands, but because the UK had sovereignty on all sorts of bits and pieces, unless you were a geographical whizz you didn’t necessarily know.’

In New York, the British and the Argentinians met to discuss the sovereignty of the islands. As February melted in to March these talks were described as ‘cordial and positive’. Potentially, if a formula could be worked out, two problems would be solved: the Falklands were only 300 miles from Argentina and, in all practical terms, it made more sense to have a working relationship than rely on Britain 8,000 miles away; and Galtieri could pose as the man who reclaimed the Malvinas. There was a problem, however: other British politicians and diplomats who’d tried these negotiations had encountered opposition – sometimes ferocious – within Britain, and Galtieri was a career soldier.

David Buey was a 20-year-old mechanic with the Fleet Air Arm working on helicopters. His squadron was based at Royal Naval Air Station Yeovilton, in Somerset, and he might have expected to be going on a tour of Northern Ireland. It was a front-line squadron and had been there before. The Falklands were something else. ‘Very few people did know where the Falklands were, I think.’

Mario Reid, a 20-year-old from Huntingdon, was a sapper with 9 Parachute Squadron of the Royal Engineers, the Parachute Regiment’s attached combat engineering unit. He was a fit young man who’d joined the engineers but volunteered, or been volunteered for, para training. ‘I didn’t mind.’ He was in barracks at Aldershot and had no idea where the Falklands were. ‘No, of course not. Most people thought they were in Scotland.’

A day after the meeting in New York the Argentinian foreign minister dismissed all talk of the ‘cordial and positive’ talks and threatened that if Britain did not relinquish sovereignty then the Argentinians would use ‘other methods’. It wasn’t looking trivial any more and, for those who could read the currents, a general and a junta which could not back down and survive were locking themselves in against a woman who could not back down and survive. Moreover, for Galtieri the word survival might involve physical dimensions; for Thatcher it would only mean her career as prime minister would be over, perhaps very quickly.

On 3 March in London a Member of Parliament asked if all precautions were being taken to defend the Falklands, and didn’t get a clear reply. Two days later the British Foreign Secretary reportedly refused to send a submarine to patrol the Falklands. A day after that, a Hercules aeroplane run by LADE, a branch of the Argentine military, landed at Port Stanley airport claiming a fuel leak. LADE had a man there and he gave the senior officers on the plane a tour of the area. Two days later Thatcher asked for plans to be drawn up in the event of an Argentinian blockade or even full-scale invasion.

On 19 March Davidoff and forty workmen returned to South Georgia and did not seek permission. In response, HMS Endurance and twenty-two Royal Marines were despatched from the Falklands.

Dave Brown, a 20-year-old born in Glasgow and now with 2nd Battalion the Parachute Regiment ‘was up at home in Leeds for the weekend, Easter leave. My plan of action was watching Leeds v Liverpool at Elland Road and then travelling over to see my sister in Holland, who was just about to have her first baby. Unfortunately we got called back. I managed to stay over for the Leeds game – which I think we lost, by the way – and then I phoned my mate up who was on guard duty because obviously nobody had mobiles in those days. I did not know where the Falklands were. I don’t think 80%, 90% of the lads did.’

On 3 April the Argentinians put significant forces ashore on South Georgia and, although the marines resisted and caused considerable damage, they could not withstand the numbers put against them.

By then Argentina had invaded the Falklands, too. The images of surrender exercised a profound impact on ordinary British people, who knew that regular British people like themselves, in distant Port Stanley and the sheep stations scattered across the two islands – East and West Falkland – were now being ruled by a military junta with a lot of blood on its hands against a constant backdrop of a lot of mothers marching in Buenos Aires for their disappeared sons.

Thatcher was fighting for her political life, while Galtieri saluted adoring, chanting multitudes.

The British Parliament authorised the sending of a Task Force and almost immediately the first RAF planes were heading towards Ascension Island, a British dependent territory since 1653, almost 2,000 miles from Angola and 1,500 from Brazil. Within a short while the airport on this tropical volcanic island became the busiest in the world. Ascension would be a forward base where supplies could be flown for when the Task Force arrived.

By now all manner of diplomacy was going on. With American President Ronald Reagan’s approval, Secretary of State Alexander Haig would shuttle from London to Buenos Aires and back trying to find common ground.

Jimmy O’Connell was a 22-year-old paratrooper from Liverpool who’d just come back from Northern Ireland: ‘I went on Easter leave. I didn’t know where the Falklands were. I don’t think anyone knew. We thought they were in Scotland – some people were saying Scotland. Truthfully, I had never heard of them.’

Graeme Golightly was a 19-year-old marine from Knowsley in Merseyside, based in Seaton Barracks, Plymouth. ‘We were in Altcar, a weapons range in Southport. We’d just gone up for some weapon training.’ Now they were recalled to Seaton Barracks ‘to get our spearhead kit all ready for whatever was going to be happening. Truthfully, no, I did not know where the Falklands were.’

The Task Force, which would have to operate at that range of 8,000 miles, comprised the navy’s four remaining major surface ships: the aircraft carriers Hermes and Invincible, and the assault ships Fearless and Intrepid. Half the nuclear submarine fleet went. Eight destroyers went: one Type 82, Bristol; two ‘County’ Class, Antrim and Glamorgan; five Type 42s, Cardiff, Coventry, Exeter – which had Stephen Wilkinson on – Glasgow and Sheffield – which had Mark Hiscutt on. There were fifteen frigates: Brilliant – which had William Field on – and Broadsword (Type 22s); Active, Alacrity, Ambuscade, Antelope, Ardent, Arrow and Avenger (Type 21s); Andromeda, Argonaut, Minerva, Penelope (Leander class); and Plymouth and Yarmouth (Rothesay class).4

There were survey ships being used as hospitals, including HMS Herald. There were Merchant Navy cargo vessels and a North Sea ferry, the Norland – which had Dave Brown on. Ocean liners were requisitioned as gigantic troop transporters: the QE2– which had Mario Reid on – and the Canberra – which had Jimmy O’Connell and Graeme Golightly on. And there were auxiliary ships like the Fort Austin – which had David Buey on.

On 25 April South Georgia was recaptured by the Royal Marines.

The British Government declared a 200-nautical-mile Exclusion Zone round the Falklands a day later. On 29 April the Task Force arrived at the Exclusion Zone and on 2 May the Argentinian cruiser General Belgrano was sunk by the Royal Navy submarine HMS Conqueror, killing 323, although it was outside the Exclusion Zone.

Up until this moment there had been a general assumption, not least among the young men in the Task Force, that a shooting war was unthinkable. The diplomats and politicians would find the common ground after all this military posturing and everyone would go home. After the Belgrano, they all sensed a shooting war had begun.

They were right.

Notes

1.www.sgisland.gs

2. news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/from_our_own…/8599404.stm

3. www.chdt.org.uk/…/Falklands

4. Type 42: guided-missile destroyer; Type 21: general-purpose escort frigate from the 1970s to the 1990s; Type 22: specialist anti-submarine warfare frigate; Rothesay class: modified Type 12 frigates named after seaside towns.

2

THE MISSILE MAN

I went inside the ship twice, the first time with my mate Bones, and while we were down there we didn’t have breathing apparatus. All we had was our gas masks. Part of your training is that you never wear a gas mask in a smoke-filled environment – it’s not built for it – but that’s all we had. It was that or nothing.

Mark Hiscutt’s father was in the army, ‘so we moved around a lot and we ended up living in Farnborough in Hampshire. I joined the Sea Cadets and I thought this looks good. I didn’t want to join the army because I didn’t want my father saying, “Well, it wasn’t like that in my days" – that’s natural. I do it to my mate’s son! – so I chose the navy. I was born in 1960 and I was sixteen and a half when I joined up.

‘I was a typical boy. I played football for the school and various clubs, I was in the Sea Cadets. We visited a lot of countries, we holidayed in Italy, driving down and back. It wasn’t the case for me that I was going into the services because of an unhappy childhood – I’d had a good childhood. I think I wanted to join the navy because of the Sea Cadets.

‘At my interview in 1976 I said I didn’t want to join the army because of the reason about dad and, secondly, I didn’t want to go to Northern Ireland. Then it was pointed out to me that there were matelots in Northern Ireland, which I didn’t know. I joined up in 1977. I did my basic training at HMS Raleigh and HMS Cambridge because I was a gunnery rate – missile man, as they call them. They are the ones who fire the guns, in my day four-and-half-inch guns, all metric now.’

Raleigh, the navy says, is the:

premier training establishment in the South West where all ratings joining the service receive the first phase of their naval training. The 9-week phase one training course is designed to be challenging, exciting, maritime in its focus and relevant to the operational environment individuals will find themselves in. It aims to develop individuals as part of a team, inculcate naval ethos and a sense of being part of the naval family.1

Cambridge, at the former Wembury Point Holiday Camp south-east of Plymouth, was ‘to provide live firing practice with conventional weapons for officers and ratings qualifying in gunnery’.2

Hiscutt joined HMS Sheffield in March 1981. The Sheffield, built at Barrow, was a guided-misile destroyer which had been commissioned in 1975. She had a complement of 287, was 410 feet long, 47 feet wide and could do a maximum 30 knots.

Hiscutt explains that ‘you had 20mm close-range weapons, that sort of thing. The four and a half is the one at the very front so if you think about a Type 42 destroyer, it’s that gun there. I don’t know exactly how fast it fired but it was pretty fast and it had a range of a couple of miles. It could knock an aircraft out and be used as naval gunfire support, which is laying rounds down against enemy targets on land, so it was a versatile and important gun. I was in the gun bay. The gun we had on the Sheffield was a Mark 8, an automatic loader. There was nobody in the turret. During action stations there were four or five of us in the gun bay and we kept loading the rounds which went up into the turret.’

The Sheffield was ‘away on deployment in the Gulf from November 1981 to March 1982 when we started Exercise SPRING TRAIN in, I think, April. We were roughly six days from home when we were turned around. We were part of SPRING TRAIN and the idea was that we were going to do a Sea Dart firing3 – because we had the missile on the front – and during it we did the firing. We got 100% because we hit the target and we were getting quite happy because we were nearly coming home, too, and I was quite happy because I was going to get married. We knew things were bubbling down south [in the South Atlantic] because we were hearing it on the radio, but we thought they wouldn’t send us because we’d been away for six months.’

On 2 April Sheffield was ordered to stand by for deployment to the Falklands. That day warships of the First Flotilla, under Rear Admiral Sandy Woodward, were in Gibraltar for SPRING TRAIN.

‘On the way back we stopped off at Gibraltar,’ Hiscutt says. ‘One morning we were woken up and told that First Lieutenant Mike Norman would make an announcement to ship’s company. He said we were going to be turned round to go down south. At the time they did something called “sons at sea” so some of the lads had their sons on board – we had been on our way home – and it was a way of keeping the family together. They’d flown down to Gibraltar and, in fact, Mike Norman’s son must have been about 13 or 14 because he was in our mess with me. I had a fair idea where the Falklands were, yes, I knew they weren’t north of Scotland.

‘We were told mail would be closing on board quite soon so we could write a quick letter home. As with everything, we weren’t allowed to say what we were doing, where we were going or anything like that. I got a piece of paper and wrote on there to my fiancée: Not coming home. Cancel the wedding. Lots of love, Mark. We should have been married on 8 May.

‘When the Task Force was being prepped, the ships that were part of the exercise became the advance party as such. When we left we refuelled with a Royal Fleet Auxillary ship which had been round the Gulf with us so it was nice that we said goodbye to them. As we broke away from the refuelling they played Don’t Cry For Me, Argentina and that was quite … funny.

‘There was nothing in the press about us on our way down, all quiet. Eventually something hit the papers – it was a small bit, Kirsty said, but I think that was when we got to Ascension Island and we were waiting for the rest of the Task Force to join us.’

The Antrim, Glamorgan, Coventry, Glasgow, Brilliant, Arrow, Plymouth and Sheffield reached Ascension on 10 April. A vast quantity of stores had been flown to the island, some not appropriate for a war zone, and a degree of chaos reigned. The official report says the procedure was to load what were considered ‘useful items’ and ‘ignore the rest. The stores situation ashore contributed to Sheffield’s decision not to take advantage of this further opportunity to offload personal possessions, valuables and inflammables.’4

‘Ascension was surreal,’ Hiscutt says. ‘We were busy because we were now prepping the ship for war. We were getting more ammo on board because [in exercises] you have practice rounds and but you get rid of them for the proper rounds. We were painting everything grey. Because the Argentinians had two Type 42 destroyers they’d bought from the British they had the same look as the Sheffield. The Sheffield had something called “ears” on its funnel – they were extra vents on top of the funnel. No other 42 in the fleet had them, but the two Argentinian ships did. So that people could identify our 42 from their 42s we painted a black stripe from the top of the funnel down to the waterline on both sides.

‘Because we had been away for six months people were sending things home, like presents they’d bought, and I remember saying to one bloke, “You are tempting fate.” I didn’t send anything home because I thought we would be going home and nothing would happen.

‘A lot of the journalists went down with the troops on the QE2 and they had a nice time, but we were on a warship. I must say we did think about it and when we were at Ascension Island – or on the way down to Ascension Island – the gunnery officer called all the gunnery rates together down the mess and we were talking about what had to be done. Someone said, “Where’s the Falklands?” We had the game of Risk, a board game where you have countries and armies, and the more countries you get the more armies you get. Someone opened that up and said, “Well, there’s the Falklands. If we attack Argentina we get two extra armies!”

‘I think there was an underlying understanding of the seriousness, because we had a job to do, but you never thought it would happen to us. I was getting letters from my sister, who is four years younger than me, and I wrote a letter back saying, “Don’t worry, we are well protected and nothing can happen to us”.’

The official report says:

Preparations for War – Stores

Ships of the Task Force were paired off, Sheffield with Active, for stores transfer. This involved Sheffield receiving a large quantity of such stores and ammunition as might be useful in a war situation, in particular 4.5-inch ammunition, chaff rockets, and some medical stores, together with food and miscellaneous items, including canteen stores, of which the ship was short following her Indian Ocean deploymant. [Hiscutt says ‘we were getting food on board and it was all Argentinian beef. It was surreal eating that.’] The ammunition then carried exceeded outfit, possibly by as much as 100% in some categories. However, it was all stowed in magazines, although inevitably not in approved stowage. For example 4.5-inch ammunition was stowed on the deck in the 4.5-inch Magazine and also in the Air Weapons Magazine adjacent to the Hangar. Back-loading to Active of unwanted stores was restricted to defective items and empties; it did not include furniture or furnishings, possessions or inflammables.

Preparations for War – Material

Material preparations were in accordance with Ships War Orders … and included the removal of pictures, taking up of carpets below 1 Deck, and stowing away of loose fittings. … Some material preparations were significant, also, from the point of view of increasing the Ship’s Company’s awareness of the reality of the threat. For example Sheffield issued, at an early stage, their Atropine and other prophylactics5 for use in the event of chemical attack.

On 14 April Brilliant, Glasgow, Sheffield, Coventry and Arrow left Ascension.

‘When we sailed south from Ascension we got our rules of engagement because apparently there was an Argentinian aircraft out looking for the Task Force,’ Hiscutt says. ‘We never saw it.

‘The first of May was a few weeks away and we knew that if nothing happened by then hostilities would start because we understood that that was an ultimatum. We knew things were getting serious because the Antrim and Yarmouth were sent to South Georgia to take that back. That’s when we knew. We were getting quite a lot of information, we were being kept up to date.

‘On the first of May we went to action stations early in the morning. The ship was somewhere off the Falklands by then. We hadn’t seen the islands because the Sheffield didn’t get close enough. We were right out on the edge acting as the first line of defence for the aircraft carriers. Then, as you came in, you got other ships so if the attackers got past us they had to get through the second wave before they got to the carriers. The carriers were the things that we had to protect.

‘So we were out there and the Harriers were going in, dropping bombs. Part of my problem is I can’t remember much between the 1st of May and the 4th of May. People have told me we had air attacks. I can’t remember that. Some things I must have blocked out. I do remember one occasion before the 4th of May we got told to brace because they thought an Exocet had been launched at us. I was in the gun bay surrounded by all the ammo and I went and stood behind the live rounds thinking, I’m not going to be injured, if I’m going to go, I want to go in one bit.

‘I knew what an Exocet was. The British navy has them so we knew about them anyway. If I remember rightly, the Antrim – one of the destroyers that was with us – had Exocets on board as well.6

‘If you read the Board of Inquiry about the Sheffield it says our ops officers were more concerned about shells being dropped from the air rather than missiles. The concern was aircraft because all we had was a four-and-a-half-inch gun. Close range we had machine guns and that was it, really, so if fighter planes came in close we were kind of sitting ducks. That’s why we were worried about aircraft. Anyway, we stayed out there.

‘When the General Belgrano was sunk we were informed of it through the broadcast in the evening. We said a prayer for the sailors. They’re sailors just like us and our problem isn’t with them. They were doing their job and it was either them or us. When we had the prayer said we thought about them. That’s when we really knew it was getting serious.

‘On the fourth of May the Sheffield was at defence watches: half the ship’s company on watch, the other half were turned in. At midday I went on watch – midday – and I went into the gun bay. There were three of us in there. Because nothing was happening we weren’t at action stations, the air-raid warning was low – the threat was low – so we were just sat in there talking. I took a cushion with me because it’s a bare metal floor. When we went to action stations I put it out of the way but we knew there would be periods of us sitting around doing nothing. We weren’t allowed to leave the gun bay because when you go in you shut the doors behind you.’

Two Super Étendards,7 armed with Exocets, had taken off from the Rio Grande Naval Air Base and were approaching. The Exocets were launched from about 6 miles away. The Sheffield had an old radar system, Type 965, and it picked up something – might have been the enemy, might have been a Harrier, might even have been a helicopter.

‘We’re sat in there and a warning came across the radio saying, “Guns stand to.” We got up and got ready then we heard, “Alarm, aircraft” – aircraft were coming in.’

On the bridge, when the Exocets were about a mile away, they were identified as missiles. They took five seconds to reach Sheffield.

‘Next thing we knew there was a whoosh going down the starboard side of the ship. I heard it. The ship kind of rocked. I didn’t hear any bang because I was in an enclosed compartment.’

One Exocet struck amidships about 8 feet above the waterline, bored into the main engine compartment and the missile’s own fuel caused a fire. The other Exocet passed harmlessly by and went into the sea.

‘Some of the lighting went out and there were people shouting over the intercom. My mate Bones, who I was run ashore with when I met my wife, came running in and said, “What’s going on?” We said, “Not too sure but we’ve lost power to the gun.” He went up forward and got power back to the gun, came back in and when the door was open we could see there was smoke and blokes were standing round outside the gun bay. They were making their way to the fo’castle through an escape hatch.’

The official inquiry stated that the missile gouged a hole 15 feet by 4 feet in the Sheffield’s side, causing:

widespread minor shock damage, typically the buckling of doors and scollapse of ladders … Large fires broke out immediately. The overwhelming initial impression is of the very rapid spread of acrid black smoke through the centre section of the ship and upward, as far as the Bridge. This smoke very quickly forced evacuation of the Machinery Control Rod, Main Communications Office, HQ1 and the Bridge, followed after a few minutes by the Ops Room … Missile propellant and burning Dieso [diesel oil] … were the main sources of this smoke, which was responsible for the early and almost complete loss of the ship’s fighting capability. Smoke clearance was unsuccessful forward and only partially successful aft.

The Firemain was breached at impact. Pressure was lost immediately and never restored … Fire fighting was largely restricted to external boundary cooling, using portable pumps and buckets, and this had little or no effect on the fires raging within the ship.

Hiscutt remembers: ‘The power had gone again. I remember looking out through the gun-bay doors and having a pair of eyes peering up at me. It was one of the blokes from the operations room. It wasn’t until 2005 when I was down at the Falklands that I remembered that person’s name. All I remembered before was the eyes. He was an able seaman, radar.

‘You think, Christ, what’s going on? We closed the door and eventually we were allowed to leave the gun bay. I think we were the last ones to leave the inside of the ship. When we went onto the fo’castle it was covered with men just sitting down because the helicopters were coming in and lifting casualties off. Once the casualties went we were detailed to go and start fighting the fire. We lost our firemain because that had been breached in a couple of places and the only way we could get water was by using pumps to suck it out of the sea. Unfortunately on the Type 42 it was stored on the quarter deck and we weren’t able to reach ours because we couldn’t get through the smoke. We were waiting for the other ships to supply them to us.

‘We were using buckets and string and bits of rope, throwing them over the side and using the water to try and do some cooling. You could see the steam coming off the fo’castle steel.’

The official inquiry states: ‘The fires gained quickly, soon embracing most of H, J and K Sections … and subsequently spreading forward and aft. Re-entry attempts were made … These were well briefed, determined attacks by men wearing fearnought suits and BA, but all wore beaten back by heat and smoke.’

Hiscutt says, ‘I went inside the ship twice. The first time I went down with my mate Bones and while we were down there we didn’t have breathing apparatus. All we had was our gas masks. Part of your training is that you never wear a gas mask in a smoke-filled environment – it’s not built for it – but that’s all we had. It was that or nothing. Bones said to me, “Ginge” – my nickname – “Have you seen Number One?” You have laundrymen on board, and Number Two, but Number One is the boss. [The first lieutenant is responsible to the captain for the crew’s domestic matters. He is sometimes known as ‘Jimmy the One’ or simply ‘Number One’.]

‘I said no I hadn’t seen Number One and we went looking for him. We looked around and couldn’t find him. Bones said, “Not feeling too well Ginge, better make our way out” and as he was climbing up the ladder he collapsed. Bones is 6 foot 6, pretty strong guy and he was my mate. I was 21, I was fit but I was a skinny little runt, no meat on me at all. I wasn’t very strong. I was having to hold him up on the ladder because if I’d let go he would have fallen a deck below.