Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

In 1933, the celebrated German economist Robert Kuczynski and his wife Berta arrived in Britain as refugees from Nazism, followed shortly afterwards by their six children. Jürgen, known to be a leading Communist, was an object of considerable concern to MI5, while Ursula, codenamed Sonya, was a colonel in Russia's Red Army who had spied on the Japanese in Manchuria. MI5 also kept extensive files on their four sisters, Brigitte, Barbara, Sabine and Renate. During the crucial early stages of the Cold War, members of the Kuczynski family proved to be prime Soviet assets as enablers and agents of influence. In Britain, Ursula controlled the spies Klaus Fuchs and Melita Norwood, without whom the Soviet atomic bomb would have been delayed for at least five years. Drawing on newly released files, Agent Sonya, MI5 and the Kuczynski Network reveals the operations of a network at the heart of Soviet intelligence in Britain. Over seventy years of espionage activity the Kuczynskis and their associates gained access to high-ranking officials in the government, civil service and justice system. For the first time, acclaimed historian David Burke tells the whole story of one of the most accomplished spy rings in history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 458

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

By the same author

The Spy Who Came in from the Co-op

The Lawn Road Flats

Russia and the British Left

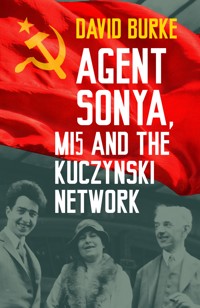

Front cover: Jürgen, Berta and Robert Kuczynski in Berlin. (Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin / Berlin-Sammlungen, Kuczynski-Nachlass)

First published 2021 as Family Betrayal: Agent Sonya, MI5 and the Kuczynski Network

This paperback edition first published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© David Burke, 2021, 2025

The right of David Burke to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75099 770 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

The History Press proudly supports

www.treesforlife.org.uk

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia

‘All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.’

Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

Preface

Introduction

1 Class Against Class

2 Jürgen

3 Ursula

4 London and Spain

5 Ursula and Brigitte

6 Turning Hitler Eastwards

7 Spying on Fellow Exiles

8 The Indian Communist Party and the BBC

9 Barbara and Renate

10 Klaus Fuchs, Melita Norwood and Geoffrey Pyke

11 The Manhattan Project and Bletchley Park

12 Jürgen and Vansittartism

13 Bridget, Arthur Long and Paul Jacot-Descombes

14 William Skardon’s Interrogation of Ursula

15 Ursula’s Flight

16 Skardon on the Kuczynski Network

17 Jürgen’s Fall

18 The Greek Civil War and the Haldane Society of Lawyers

19 Renate, Melita Norwood and the Rifkind Criteria

Conclusion

Appendix 1: The Evolution of the GRU and the KGB

Appendix 2: A Note on British Intelligence

Appendix 3: William Scanlon Murphy to David Burke, 7 July 2016

Appendix 4: William Scanlon Murphy to David Burke, 17 July 2016

Notes

Bibliography

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

All images are courtesy of the author’s collection unless otherwise stated. While every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders, the publishers would be pleased to rectify at the earliest opportunity any errors or omissions brought to their attention.

1 Robert Kuczynski in his student days (Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin / Berlin-Sammlungen, Kuczynski-Nachlass)

2 Robert Kuczynski (ullstein bild via Getty Images)

3 Robert, Berta and Jürgen Kuczynski in Berlin (Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin / Berlin-Sammlungen, Kuczynski-Nachlass)

4 Jürgen Kuczynski at the Brookings Institution, Washington, DC (Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin / Berlin-Sammlungen, Kuczynski-Nachlass)

5 Marguerite Steinfeld (Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin / Berlin-Sammlungen, Kuczynski-Nachlass)

6 Ursula Kuczynski in 1927

7 Fascist demonstration and counterdemonstration in Hyde Park, London, 9 September 1934 (© Illustrated London News Ltd / Mary Evans)

8 Lawn Road Flats, Hampstead, c 1950 (Photo by John Maltby © Pyrok Ltd Courtesy of the University of East Anglia, Pritchard Papers Collection)

9 Ursula Kuczynski in Switzerland, 1938

10 Leon Beurton

11 Melita Norwood

12 Klaus Fuchs

13 Jürgen Kuczynski’s membership card for the Free German League of Culture in England (Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin / Berlin-Sammlungen, Kuczynski-Nachlass)

14 Geoffrey Pyke (Alamy)

15 Portrait of Robert by Berta Kuczynski, 1942 (Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin / Berlin-Sammlungen, Kuczynski-Nachlass)

16 William Skardon (AP / Shutterstock)

17 Jürgen Kuczynski in American uniform, March 1945 (Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin / Berlin- Sammlungen, Kuczynski-Nachlass)

18 Certificate awarded to Jürgen by the United States Strategic Bombing Survey, August 1945 (Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin / Berlin-Sammlungen, Kuczynski-Nachlass)

19 Jimmy Friell’s Daily Worker cartoon on the Greek elections of 1946

20 Cover of the first edition of Larousse Gastronomique

21 Front of card sent by Renate Simpson to Melita Norwood

22 Back of card sent by Renate Simpson to Melita Norwood

PREFACE

On 15 February 2003, the UK’s biggest anti-war demonstration took place against George W. Bush and Tony Blair’s Coalition of the Willing’s declaration of war against Iraq; up to 2 million people took part. The march was organised by Stop the War Coalition, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, and the Muslim Association of Great Britain. I took part and walked for a while beside the veteran British Jewish Communist Jack Gaster, who was then 96 years of age. I had interviewed Gaster the previous week about his communist activities and his work with a number of Jewish Communists in Britain, including members of the Kuczynski family and the atomic spy Melita Norwood, whose controller Agent Sonya is the main subject of this book. With the current conflict in Gaza showing no signs of reaching a humanitarian conclusion that would guarantee the human rights of all involved in this tragic conflict, it is a good moment to remind ourselves that, not only were there a number of Jewish Communists who were willing to engage in espionage for the Soviet Union, but who were also ready to build communism. Theirs was a far different perception of Zionism than Benjamin Netanyahu’s and Bezalel Smotrich’s far-right party in Israel.

The extent to which Jewish Communism was largely a response to Nazi ideology and their attack upon the Jews, as opposed to emerging out of any real sympathy with the aims of Stalin or even the Bolsheviks (Jewish and otherwise), who had made the 1917 Revolution, remains an intriguing question. Writing on the subject of Jewish Communism in 1920, Winston Churchill maintained that the Jews had been, and remain, the mainstay of the Bolshevik Revolution. He wrote:

With the notable exception of Lenin, the majority of the leading figures are Jews. Moreover, the principal inspiration and driving power comes from the Jewish leaders. Thus Tchitcherin, a pure Russian, is eclipsed by his nominal subordinate Litvinoff, and the Russians like Bukharin and Lunacharski cannot be compared with the power of Trotsky, or of Zinovieff, the Dictator of the Red Citadel (Petrograd), or of Krasin or Radek – all Jews!

To allay fears of the Jewish threat, Churchill went on to praise the idealism of the ‘Zionist Jew’, which he promoted as an antidote to the ‘Bolshevik Jew’.1 For Churchill and the British Establishment, the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, under British auspices, would serve as both ‘a refuge for the oppressed’ and the embodiment of ‘a national idea of a commanding character … especially in harmony with the truest interests of the British Empire’. Thus, for Jewish Communists the principal ideological foe was not simply Nazism and the existential threat it posed to European Jewry, but also the British Establishment’s concept of Zionism and the ambitions of the British Empire. Thus, the internationalist creed of Communism was a strong core tenet of their beliefs, while their support for Stalinism and Communism led them to confront the imperialism that underpinned the British Empire and sought a Jewish centre in the Middle East. When German Jewish Communist refugees came to Britain to escape the horrors of Nazism, therefore, they had few qualms when it came to working for the Soviet Union and engaging in espionage against their British hosts. The Soviet Union, after all, was an ally against Nazi Germany.

The full title of the hardback edition of this book, Family Betrayal: Agent Sonya, MI5 and the Kuczynski Network, generated a sense of outrage among many conservatives and sympathisers of the Kuczynskis alike, as the Kuczynski family’s involvement in espionage against the British Empire has often been denounced as a betrayal of the good offices gifted to refugees from Nazism. But it could equally be argued that the Kuczynskis deserve some praise for sticking to their principles and not betraying their Communist ideology; nor did they simply see Communism as a vehicle for their anti-Nazi activity. However, this book does cover a period of over seventy years of espionage activity undertaken by the Kuczynski family and we should not be surprised if, at times, their commitment to the Communist ideal wavered; nor should we be surprised that members of the family successfully accommodated themselves to their host nation. The concept of betrayal becomes blurred, as does the question of family allegiance and loyalty to other left-wing individuals who came into their orbit, as one would expect.

The Jewish question, then as now, remains a crucial factor in any understanding of the espionage the Kuczynskis undertook for ideological, as opposed to financial, reasons. Churchill’s article, ‘Zionism versus Bolshevism’, is of interest here, not only for the light it throws on the motives behind the family’s organised spying on the British Empire, but also for Churchill’s barely disguised anti-Semitism:

… it may well be that this same astonishing race [the Jews] may at the present time be in the actual process of producing another system of morals and philosophy [Bolshevism], as malevolent as Christianity was benevolent, which, if not arrested, would shatter irretrievably all that Christianity has rendered possible. It would almost seem as if the gospel of Christ were destined to originate among the same people; and that this mystic and mysterious race had been chosen for the supreme manifestations, both of the divine and the diabolical.2

David Burke,Cambridge,July 2025

INTRODUCTION

The two greatest British secrets of the Second World War were undoubtedly the atomic bomb programme and the breaking of the German codes at Bletchley Park. Hitherto, much has been written about how the Soviets gained the secrets of the atomic bomb, but very little has been written about the Soviet infiltration of Bletchley Park. At the centre of the Soviet campaign to access Britain’s wartime secrets was a remarkable family of Communist refugees from Nazism, the Kuczynskis. There were eight family members and five marriage partners either directly active, or in supporting roles, working with Russian intelligence: the patriarch and matriarch Robert and Berta, their son Jürgen, and daughters Ursula, Brigitte, Barbara, Sabine and Renate. They were a family whose work for Soviet intelligence would ensure the success of the Russian intelligence offensive against Great Britain for much of the twentieth century. Their respective careers fitted neatly into Soviet intelligence activity in Britain that targeted Left-wing elements and fellow-travellers. This continued long after any ideological solidarity between the Soviet Union and organised labour in Britain had disappeared from the Labour Party’s make-up.

The Kuczynskis were not only a family who spied but also one of the chief channels of leakage of information to the Soviets from a variety of sources. During almost seventy years of intelligence activity the Kuczynski family gained access to high-ranking civil servants in the Board of Trade, Ministry of Information, the British Council, the Ministry of Labour and National Service, the BBC, the Ministry of Power, Ministry of Economic Warfare, the Atomic Energy Research Establishment, RAF Harwell, Members of Parliament and the legal profession; many of their contacts were Communists or fellow-travellers, and at one time they included Arthur Drew, Private Secretary to the Secretary of State for War, who worked closely with a number of prominent politicians, among them Emmanuel Shinwell, Sir John Grigg and John Profumo. The Kuczynskis created organic networks: an agent once recruited began recruiting friends from various backgrounds.

One of the most significant spy rings in the early Cold War, the Kuczynski network was targeted on Britain’s emerging atomic bomb programme and Bletchley Park. It was, for a time, based in what was one of London’s most fashionable buildings in leafy Hampstead – the Lawn Road Flats, a haven for spies. No fewer than seven secret agents for Stalin’s Russia lived here in the 1930s and ’40s including an Austrian-Jewish Communist, Arnold Deutsch, the controller of the group of spies known as the Cambridge Five – Anthony Blunt, Guy Burgess, John Cairncross, Donald Maclean and Kim Philby. Brigitte Kuczynski, code name ‘Joyce’, arrived in Britain from Geneva on 26 March 1934 and moved into the Lawn Road Flats on 4 July 1936. From there she recruited two important British spies, Alexander Foote and Leon Beurton, who were sent to Switzerland to work with Ursula Kuczynski, code name ‘Sonya’.

Ursula Kuczynski had previously worked as a Soviet spy in Manchuria and was an exceptionally adept encrypter, able to use Morse code faster than any other agent on Soviet military intelligence’s books. In London, Jürgen Kuczynski, code name ‘Peter’, another Lawn Road Flats resident, was the vital link between the Kuczynskis and the ‘legal’ resident at the Soviet Embassy, and was on friendly terms with the Soviet Ambassador, Ivan Maisky. An important asset, he collected intelligence on schisms within the Labour Party and introduced his sister Ursula to the émigré physicist Klaus Fuchs, who was then working on the joint Anglo-American bomb project. From 1943, Ursula lived under cover as a rural Oxfordshire housewife and mother, while transmitting nuclear secrets to Moscow from an adapted washing line in her garden in the Cotswold village of Great Rollright. She described how she would walk down country lanes with Fuchs – they would affect to be young lovers – while he handed over atomic formulae. She also controlled the atomic bomb spy Melita Norwood until 1944 when Moscow Centre and Beria’s NKVD1 took over the handling of the atomic bomb spies from Soviet military intelligence, the GRU.2 Following his arrest, Fuchs named Ursula as his controller. MI5, however, got nowhere in their attempts to interview her about her espionage activities, and before the Kuczynski network could be fully unravelled both Ursula and Jürgen had beaten a hasty retreat to East Berlin.

Among Barbara Kuczynski’s acquaintances were Margot Heinemann and Guy Burgess, and through Margot, Anthony Blunt and Donald Maclean. Barbara’s husband, Duncan Macrae Taylor, a well-connected Lowland Scot, trained as a wireless operator with the RAF and served as an intelligence officer in Cairo before being posted to Bletchley Park. Barbara and Duncan both joined the Labour Party, where they cultivated a number of senior party officials, becoming what one acquaintance of the Taylors called ‘social enablers’. The youngest of the Kuczynski daughters, Renate, code name ‘Katie’, was recruited to Soviet military intelligence in 1939 by her sister Ursula. Working closely with Barbara, she introduced Communist sympathisers and fellow-travellers into the government’s Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park.

How legitimate is spying in defence of a cause? Is it possible to confer the honourable title of anti-Nazi resistance on the Kuczynski family, and have done with it? Or should we condemn the family for its espionage activities on behalf of the Soviet Union that, in the main, targeted Great Britain and the British Empire? As an ideology based on internationalism, Soviet Communism found it relatively easy to recruit outside its borders. Under Stalin’s dictatorship, however, that internationalism turned inwards to promote the defence of one nation state above all others. Those spies still acting in what they believed to be the best interests of internationalism succumbed to the blandishments of Stalinism. A vast array of Communist propagandists and fellow-travellers were prepared to accept the Soviet Union ‘as if it were, in reality, what it was on paper’.3

In 1958, two years after Nikita Khrushchev’s speech to the Twentieth Party Congress of the Soviet Union, the British historian Henry Pelling wrote of his fascination with the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), stating that ‘there can be few topics more worthy of exploration than the problem of how it came to pass, that a band of British citizens could sacrifice themselves so completely … to the service of a dictatorship in another country.’4 In the case of the Kuczynskis, that problem was compounded by an added dimension. As German refugees living in Britain they were not merely prepared to spy for the Soviet Union against Germany, but were prepared to spy against the interests of their adopted country. In some respects, they found this quite straightforward owing to their acceptance by British Communists working for the revolutionary overthrow of their own government. This was further enhanced by the anti-imperialist work of the CPGB, which was actively supported by the Kuczynskis. The underground work of Brigitte with the Director of the CPGB’s Colonial Affairs Committee, Michael Carritt, who had at one time served as a British Security and District Officer in the Indian Civil Service, was a good example of this. Ursula’s work with the Communist Party of China, too, was directed against both Japanese and British imperial interests in the Far East. Jürgen’s openly proclaimed support for the Nazi–Soviet pact was largely based on antipathy towards the British Empire and the growing influence of Wall Street in global affairs. Furthermore, when Sabine Kuczynski’s husband, the Communist lawyer Francis Loeffler, defended opponents of the Greek monarchy charged with treason, was he guilty of subversion? The legitimate activities of the Kuczynskis brought them into contact with reformist socialists in the Labour Party, the legal apparatus, government ministries, trade unionists and others in their pursuit of a Stalinist vision of Communism and resistance to Fascism.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the opening of Stasi archives, a more detailed picture has emerged not only of Soviet espionage in Germany, but also of Communist resistance to Hitler in Germany. Communist resistance can be said to have taken place on two levels. Firstly, there was the opposition of rank-and-file Communists who believed that the defeat of Nazism would be followed by the victory of German Communism over capitalism. Secondly, there was an elite group of German intelligence practitioners who believed that German Communism could only be achieved by guaranteeing the security of the Soviet State. This second group included the Kuczynskis and formed the nucleus of the German–Soviet intelligence secret service operating out of Moscow Centre in both Nazi Germany and the UK. Traditional historiography has, hitherto, shied away from the second group while downgrading the first. By doing so historians have created the erroneous impression that there was no serious opposition to Hitler before 1937 and that when it appeared it came ‘almost exclusively from a small minority of churchmen, aristocrats and other conservatives’.5 Such an approach ignores the contribution of those Communists, like the Kuczynskis, to the defeat of Nazism. Many historians prefer to fall back on a crude reductionism that sees the Communist resistance as another form of totalitarianism comparable to that of National Socialism itself, thereby stripping its activities of heroism.6

There is, of course, the question of the German Communist refugees’ gratitude to Britain, the country that not only offered the Kuczynskis asylum but also guaranteed their freedom from want. Did the Kuczynskis, at least during the period of the USSR’s alliance with Britain and the United States, make a worthwhile contribution to the Allied war effort, while advancing the cause of Communism and Stalin’s Soviet Union?

The Kuczynskis’ activities on behalf of the Soviet Union can be divided into five distinct periods: pre-Hitler Germany, covering the years from the Russian Revolution of 1917 to Hitler’s accession to power in January 1933; Hitler’s period in power down to the signing of the Nazi–Soviet Pact and the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939; Communist opposition to the imperialist war, which covers the period from the outbreak of war on 1 September 1939 to the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941; the period of the Second World War and Great Patriotic War, 1941–45; and finally the Cold War that followed. Throughout, Stalinism as a system influenced events. Agent Sonya, MI5 and the Kuczynski Network, therefore, takes as its starting point Stalin and German Communism and the ideological ‘progression’ of the Kuczynskis until Hitler came to power in January 1933. By linking four main areas of Soviet espionage activity in the UK – the race against time to build a Soviet atomic bomb; the garnering of political intelligence from inside the Labour Party; the penetration of Bletchley Park and the British Civil Service – Agent Sonya, MI5 and the Kuczynski Network sheds new light on the Soviet Union’s intelligence offensive against Great Britain during the twentieth century and MI5’s efforts to both thwart their attacks and to counter subversion.

CHAPTER ONE

CLASS AGAINST CLASS

Robert René Kuczynski was born on 12 August 1876 in Berlin, the son of a successful banker. On 1 December 1903, he married Berta Gradenwitz, an artist who was born into a land-owning family on 30 June 1879 in Cottbus.

The Kuczynskis were a comfortable, German bourgeois family of Jewish origin that did not practise any faith. Their large lakeside villa by Berlin’s Schlachtensee, ‘the gift of a wealthy grandfather’,1 boasted an impressive library bought chiefly from the Hungarian-Jewish Communist writer Arthur Holitscher, described by the Kuczynskis’ eldest daughter, Ursula, as a frequent visitor to Schlachtensee and a ‘friend of the Soviet Union’.2 Among the volumes on the shelves were works by Thomas Mann, George Bernard Shaw, Upton Sinclair and John Galsworthy.

In her autobiography, Ursula described the family’s economic status in Berlin as barely adequate. Despite their spacious and by all accounts impressive surroundings, Robert’s salary from the Statistical Office of Berlin3 was insufficient to provide more than a ‘relatively simple standard of living’.4 Ursula regarded her father as ‘more of an academic than an official’ whose modest income would not support his large family made up of one son, Jürgen (b. 1904), and five daughters, Ursula (b. 1907), Brigitte (b. 1910), Barbara (b. 1913), Sabine (b. 1919) and Renate (b. 1923). Nevertheless, the family library was overflowing and Berta was said to be ‘frantic over this squandering of money on books’.5

Sabine was less damning in her description of the family’s economic circumstances and described how she was ‘brought up against a well-to-do middle-class background’, with ‘the tremendous advantage of intelligent progressive thinking parents’. Her childhood, she wrote, ‘was spent in an atmosphere where art and books, reading and learning were encouraged’.6

Robert in 1919 would probably have described himself as a liberal progressive with strong social democratic beliefs. With widespread food scarcity in Europe, he had joined the Fight the Famine Council (FFC)7 and assisted, as a statistician, in the ‘collection of the facts and suggested remedies’ to alleviate the situation in Russia, Finland, Poland, Czechoslovakia, the Balkans and Armenia; serious food shortages in Turkey, Bulgaria and Italy were also dealt with by the FFC. In November 1919, the FFC held its first International Economic Conference at Caxton Hall in Westminster, organised by Charles Alfred Cripps, Lord Parmoor, Sir George Paish, William Beveridge and John Maynard Keynes. All four were leading liberal progressives on the Left wing of liberalism in Britain. In 1921 Robert attended the organisation’s International Conference for Economic Reconstruction held at the Caxton Hall between 11 and 13 October, where he first made the acquaintance of Britain’s future wartime Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Stafford Cripps, the youngest son of Charles Alfred Cripps, and other progressive notables.8

Earlier that year the FFC had published the Soviet government’s worldwide appeal for aid, The Famine in Russia: Russia Appeals to the World, and in its report on the Caxton Hall conference issued an appeal to world leaders and the League of Nations to address the economic problems that besieged Europe under the title The Needs of Europe, Its Economic Reconstruction. The report called for German reparations to be fixed at a level that Germany could afford to pay and appealed for the restoration of production in Russia and renewed trade relations with Moscow.9 The conference identified two critical factors that it believed were preventing European economic reconstruction and threatening world peace: runaway inflation in Germany and the persistence of economies in Europe dependent on heavy industry. The two together were creating a balance of payments crisis that was fuelling political and social unrest. Militarism, the conference warned, had erroneously been accepted as the most direct way out of the crisis:

The Conference desires to record its conviction that Europe cannot obtain either credit guarantees or the credits themselves until the various nations reduce their military outlays, make a real effort to curtail their governmental expenditure, endeavour to restore the equilibrium to the budget, and thus indicate their intention to stop the issue both of paper currency and of governmental loans for other than productive purposes.10

This was the central message that Robert brought back to Germany from London in 1921. The world economic crisis, he argued, was drawing the German working class closer to the Russian revolution. His analysis chimed with the activities of the German Communist Willi Münzenberg, who had established Workers International Relief (WIR) in Berlin, also known as International Workers’ Aid (IWA), in September 1921. Münzenberg’s organisation, an adjunct of the Communist International, promoted international working-class solidarity by channelling relief from various organisations and Communist parties to famine-stricken Russia. As the first Communist organisation to make inroads into non-Communist circles of workers and intellectuals, it made an important departure from orthodox Communist practice. Under Münzenberg’s tutelage, Germany became an important springboard for Agitation and Propaganda (‘agitprop’)11 and donations to Russia poured in. Twenty-one shiploads of material left Germany for Russia in 1921, increasing to seventy-eight shiploads in 1922. As the German Communist Ruth Fischer observed, its effect on the economic crisis gripping a country the size of Russia could only have been slight but ‘as propaganda the value of these collections was inestimable: everyone who donated his little bit felt tied to the workers’ fatherland’.12

Münzenberg has rightly been seen as the architect of a scheme to enlist and harness intellectuals worldwide in support of the Communists’ Soviet experiment.13 It was under his guardianship that the phenomenon of the fellow-traveller, a ‘sympathiser’ capable of promoting the Communist cause without becoming a fully paid-up member of a national Communist party, was created.14 Robert Kuczynski served as an important link between Münzenberg and liberal–socialist–pacifist circles.15 In this capacity he was protected from the unending doctrinal disputes and the internal strife within the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (KPD) that prevented the formation of a united front between the Communists and the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD) throughout the period of the Weimar Republic. The failure of the leaders of the KPD and SPD to build a united front along the lines ordained by the Communist International (Comintern) in 192216 had its roots in the Russian Politburo’s response to two key events: the French and Belgian occupation of the Rhine-Ruhr on 11 January 192317 and the debacle of the failed 1923 German October Revolution.

According to Ruth Fischer, the Russian Politburo jettisoned the united front policy soon after the KPD had agreed to unite with the SPD leadership in a programme of strict disobedience to the occupation authorities and to fight for a workers’ government. However, the tactic was condemned by the Russian Politburo as a ‘Right deviation’ and at a secret conference in Moscow German Communists were instructed to intensify the struggle for power, particularly in the occupied Rhine-Ruhr region.18 Following a nationwide general strike in Germany in mid-August, the Russian Politburo ‘discussed the question of a German revolution in all its details’.19 A committee of four was appointed to supervise the preparations; Stalin alone advised caution. In September a small revolutionary committee of German and Russian officers was brought together to direct the uprising. ‘Governments of proletarian defence’ were formed in Saxony and Thuringia on 10 and 16 October respectively, composed of representatives from both the SPD and KPD.20 On 20 October the Central Committee of the KPD agreed unanimously to call a general strike and prepared to launch an armed struggle. The absolute refusal of the SPD to endorse the KPD’s proposals, however, spread confusion and the revolution was abruptly called off. The following day, the German Army intervened and the coalition governments of Saxony and Thuringia were overthrown. On 2 November SPD members in the Grand Coalition cabinet tendered their resignations, prompting the Central Committee of the KPD to launch an attack on the leaders of the SPD, who they condemned for failing to support the revolutionary aspirations of the German working class.21 Later that month the KPD was declared illegal.22

The lessons of the German October were not lost on Stalin, whose theory of ‘Socialism in One Country’ – that the building up of the Soviet Union’s industrial base and military might must take precedence over the export of revolution abroad – gained widespread support in the Russian Politburo. By 1924 ‘Socialism in One Country’ was the dominant premise. The Nazis, meanwhile, sowed further divisions among Germany’s working class by presenting militant nationalism as an alternative to proletarian revolution. Any lingering hopes of a united front between the leaders of the two working-class parties were finally discarded when the Comintern and the KPD denounced the SPD as ‘accomplices of Fascism’.23 In January 1924 the President of the Communist International, Grigori Zinoviev, condemned the SPD for forming ‘a life and death alliance against the proletarian revolution’ with the Reichswehr.24 The tactic of ‘unity from above’, he urged, must give way to ‘unity from below’:

The essence of the matter consists in this, that General Seeckt25 is a fascist like others, that the leaders of German Social Democracy have become Fascist through and through, that they have in fact formed a life and death alliance against the proletarian revolution with General Seeckt, this German Kolchak.26 That is the reason why our whole attitude towards Social Democracy needs revising … The slogan ‘unity from below’ must become a living reality.27

Zinoviev’s instructions could not easily be ignored. At this time the KPD could claim between 125,000 and 135,000 members and was – by German standards – a weak organisation; whereas the apparatus of the Party remained strong largely owing to Moscow’s grip over important elements within the KPD:

The Central Committee, its secretaries, editors, technical employees

850

Newspaper and printing plants, including advertising staff

1,800

Book shops, with associated agitprop groups

200

Trade union employees (principally in Stuttgart, Berlin, Halle, Thuringia, Chemnitz)

200

Sick benefit societies

150

International Workers’ Aid, with affiliated newspapers

50

Red Aid, including children’s homes in Thuringia

50

German employees of Soviet institutions (Soviet Embassy, trade legations in Berlin, Leipzig, and Hamburg, the Ostbank, various German–Russian corporations)

1,000

Total:

4,30028

All these employees, Ruth Fischer pointed out, depended upon Moscow for their positions. Swelling their number were the ‘invisible undercover agents’, roughly amounting to the same number. If these figures are correct, she maintained, ‘almost one twelfth of the party membership was in direct Russian pay’.29

In 1926 the counter-espionage section of the GRU founded the first Lenin School in Moscow where, in a secret annex on the outskirts of the city, conspiratorial methods were taught. As the revolutionary prospects in Germany faded, the ‘invisible undercover agents’ concentrated on espionage in various fields of activity. ‘Out of the ruins of the Communist revolution,’ wrote one of Stalin’s principal agents, ‘we built in Germany for Soviet Russia a brilliant intelligence service, the envy of every other nation.’30 A secret apparatus began to dominate the internal life of the KPD – die Nachrichten (intelligence) – also known as the N-Group. Between 1926 and 1929 the N-Group, controlled by OGPU31 men, prepared a complete index of German Communists. The future East German leader Walter Ulbricht became the principal contact between the Russian secret service and the German party and ‘Berlin became a second headquarters for Russian agents penetrating the rest of Europe.’32 The KPD became less of a political party and more of a pressure group along the lines of their British counterparts in the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). Nowhere was this more evident than in the part played by the Party in the plebiscite to expropriate the Hohenzollerns.

The Kaiser’s considerable fortune had been sequestered by Prussia at the end of the First World War. However, confiscation of his entire wealth was postponed indefinitely by a dispute, dragging through the courts and the Reichstag Judiciary Committee, on whether William II should be compensated for his losses. When the SPD proposed a Reichstag Bill to settle the matter, the Communists intervened and demanded that the imperial fortune be confiscated without any compensation whatsoever. Their stand won widespread support among the SPD rank-and-file and other liberal groups and led to the setting up of various liberal–socialist–Communist committees under the leadership of Robert Kuczynski, who expertly cultivated ‘unity from below’ within the framework of the forgotten united front:

At that time the Peace Cartel33 was the influential centre of all specific cultural political movements and groups within the German republic; and if this Cartel once made common cause with the KPD, the SPD could not remain aloof without making itself ridiculous, so within a few days, and with bad grace, it joined the Committee against the Royal Indemnity. The leadership was de facto in the hands of the Communists and a non-party man, naturally Dr. Robert KUCZYNSKI was elected as president, it was the Communist Party’s reward to him for his attitude.

The general secretary of the German League for the Rights of Man,34 the pacifist Otto Lehmann-Ruessbueldt, worked closely with Robert Kuczynski on the Committee. In 1941 he offered this telling character sketch of Robert to the British security service, MI5:

I have brought up the Royal Indemnity because it is characteristic of Dr. KUCZYNSKI. As a politician he was a popular radical, courageous and soft to the point of demagogy, officially divided from the Communists, but in actual fact very near to them and because he was not a party member, protected from being drawn into the internal party strife and quarrels. He belonged to the circle of ‘bourgeois sympathisers’ so painstakingly cultivated by the KPD. I am convinced that KUCZYNSKI has never actually belonged to the KPD himself. However, as he is very vain, he welcomed the honours done to him by a great Party.35

Lehmann-Ruessbueldt later claimed that the action taken against the Royal Indemnity (Fürstenabfindung) ‘was wrecked through Communist-Radical stupidity, and social democratic and left-wing slackness’. Under the deal the government had allowed the royal family to hold on to part of their possessions and to have the use of Cecilienhof, a sprawling neo-Tudor palace in Potsdam.36 In July 1941 Lehmann-Ruessbueldt, by now an MI5 informant inside London’s German émigré community, told the security service that he ‘remembered quite clearly what attitude Robert Kuczynski took up at that time’:

The President Prof. Ludwig QUIDDE, subsequently a nobel prize winner …, had moved that the wishes of the people should be the basis of the claim; that the former dynasty should be deprived of all their property, except for a capital sum, the interest on which would amount to 1000 RM a month (£50). Respectively: a state pension of 1000 RM per month. This proposal was reasonable. On this basis, a popular majority would probably have been achieved. The Social democrats who at that time held aloof from the movement, would certainly have been won over by these moderate demands, likewise a large number of bourgeois democrats and Catholics, and even certain petit-bourgeois nationalists. In the negotiations which took place with the Communists about this matter, our Peace cartel was represented by the President QUIDDE, Dr. Helene STOCKER and KUCZYNSKI. Dr. STOCKER (at that time one of my closest collaborators) agreed with QUIDDE’s proposal; we were revolutionary but not radical (just as I am today). Originally KUCZYNSKI also agreed. The Communists immediately declared that they would not tolerate a compromise. All or nothing. The Royal families must be stripped of everything, not a pfennig must be left to them, only such a decision would be popular etc. etc. Whereupon KUCZYNSKI declared that if this was the opinion of our Communist friends, we must agree to it, because without the KPD the action could not be begun, and it must be begun.37

Robert Kuczynski’s strident support for the Communists and his ability to marshal the moderates behind the Communists’ campaign against the Hohenzollerns encouraged the Monarchists to organise a vigorous counter-campaign. In an open letter, President Hindenburg complained that the ‘proposed expropriation was a great injustice, a regrettable lack of tradition, a crude ingratitude’ that ‘violated the concept of private property on which the Weimar Republic was based’.38 A preliminary vote to determine whether or not a referendum should be held on the actual question of expropriation was held on 20 June 1926. Twenty million ‘yes’ votes were required to hold the plebiscite but out of the almost 40 million eligible voters, only 15 million voted. The result was a sweeping victory for Robert and his liberal–socialist–Communist coalition, with 14.5 million voting ‘Yes’ and 0.5 million registering a ‘No’ vote. The number of voters, however, fell far below the 20 million required. The nationalists had simply boycotted the vote; Robert’s campaign had so seriously disrupted the nationalist Right that they turned away from the Hohenzollerns and began looking towards Hitler and the Nazis for salvation.

In the face of a growing Nazi threat, Robert was reluctant to abandon the tactic of the united front completely, and continued to urge unity with the SPD against Fascism despite Nikolai Bukharin’s calls in 1928 for the struggle against the social democratic parties to be intensified under the slogan ‘Class against Class’.39 According to the new policy, social democracy, by securing agreements with the capitalist class, actively strengthened capitalist infrastructure and was, therefore, to be regarded as a greater threat to Communism than Fascism. The ‘main task of the party’ was ‘to break the influence of the social democratic counter-revolutionaries on the masses’.40 Robert Kuczynski, while accepting the new line, remained reluctant to throw over completely his united-front beliefs. His one-time colleague in the Fürstenabfindung, Lehmann-Ruessbueldt, complained at the end of 1928 that the KPD had become ‘more left and idiotic’ and criticised ‘the party openly’. Robert, he recalled, ‘refrained from all open criticism and so remained the Communists’ whiteheaded boy. … Intellectual conscience is not KUCZYNSKI’s strongpoint.’41

In Germany, ‘Class against Class’ found considerable support following the shooting of unarmed Communist demonstrators on 1 May 1929 by the Berlin police, then under the control of the SPD Police Chief, Karl Zörgiebel. The SPD was roundly condemned as ‘the enemy of the working class’ and denounced in Die Rote Fahne (The Red Banner) for its ‘Social fascist regime of terror’.42 At the KPD’s Twelfth Party Congress (16–19 June 1929), Ernst Thälmann, chairman of the KPD, described the newly elected coalition government under Hermann Müller (SPD)43 as ‘an essentially dangerous form of Fascist development, the form of Social Fascism [which] consists in paving the way for fascist dictatorship under the cloak of the so-called “pure democracy”’.44 He insisted that Fascism could not be defeated without first defeating social democracy. It was the wrong speech at the wrong time. Germany in 1929 descended into a spiral of violence with politically motivated brawls, muggings and stabbings commonplace. During these years the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, NSDAP) grew as the Communists declined. The grave economic crisis that followed the Wall Street Crash of 1929 paved the way for the Nazis’ first decisive triumph in the elections of September 1930, when it became the second-largest party in the Reichstag, with 107 seats. The nationalist Right was in the ascendancy and xenophobia was seized upon by Hitler as a path to power. An agreement between the old ruling caste and the Nazi Party ensured Hitler’s success. Industrial rationalisation and the great unemployment crisis of 1931–32 caused such distress among the German working class that a new proletariat emerged, responsive to a new national feeling and ready to receive National Socialism as the antidote to the omnipotence of money. Millions followed Hitler. The establishment of the Third Reich on 30 January 1933 created an order of things under which the Nazi Party would be able to impose its domination over the entire German nation, setting up a machinery of power that made resistance all but impossible. In February, an appeal to Communists and Social Democrats to unite against Nazism written by Robert Kuczynski was posted on hoardings across Berlin. As a result his villa was ransacked by the Gestapo and he fled to Czechoslovakia, leaving his family behind in Berlin. From Prague he went to Geneva, where he undertook honorary work for the League of Nations before moving to London on 11 September 1933. He was conditionally granted entry but on 26 October this was cancelled by the Home Office, although he was not deported.

CHAPTER TWO

JÜRGEN

MI5’s knowledge of the Kuczynski family’s German Communist activities was based on a long association between the Metropolitan Police’s Special Branch and the Prussian secret police, stretching back to the 1920s.1 The security service opened a Kuczynski file as early as 1928, based on information from MI6 agents working inside Germany. The file was at first simply a KAEOT – ‘Keep an Eye on Them’ – commonly known as a K file.2 In August 1930 an informal agreement was reached between Special Branch and the Prussian secret police that ‘closer collaboration’ between the two intelligence bodies ‘in respect of Bolshevik propaganda and intrigue would be helpful’.3 As a result, Guy Liddell, Special Branch’s leading expert on Communist subversion, visited Berlin on 10 October 1930 to meet with his opposite number in Germany. On 30 March 1933, MI5 opened deliberations with their new Nazi counterparts in the Prussian secret police, soon to be renamed the Gestapo. The initiative had been taken by the Germans, who claimed to have discovered documents detailing the Comintern’s attempts to spread unrest throughout the British Empire.4 Liddell, who had been transferred to MI5 in 1931, was given access to official files and made arrangements for relevant documents to be copied and forwarded to London via Captain Frank Foley, the Passport Control Officer at the British Embassy in Berlin. Liddell produced a lengthy report entitled ‘The Liquidation of Communism and Left-wing Socialism in Germany’, which would form the basis for future MI5 surveillance of German Left-wing refugees from Hitler’s terror, including the Kuczynskis. Robert’s son Jürgen was of particular interest.

Born on 17 September 1904 in Elberfeld, Germany, Jürgen had received a good education studying philosophy and history in Berlin, Heidelberg and Erlangen, where he was awarded a doctorate on the subject of ‘Economic Value – an economic, historical, sociological and historical-philosophical view’. A high-flyer, he had worked in a Berlin bank in 1925 and between 1926 and 1929 had studied economics at the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC, where he published his first major work, Back to Marx, and ran the statistical section of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in Washington; he also worked for the Bureau of Labor Statistics. He was very close to his father, who between 1925 and 1931 worked six months of the year at the Brookings Institution. In 1928 Jürgen married Marguerite Steinfeld (born in Bischheim, Strasbourg in Alsace, on 5 December 1904), and in 1929 the couple published a joint work, The Factory Worker in the American Economy. Marguerite had been living in the USA for seven years before her marriage to Jürgen.

Urbane with the appearance of a courtly diplomat, Jürgen had been brought to the attention of MI5 in 1931, when he wrote to W.H. Williams, Secretary of the Labour Research Department in London, asking for their British Imperialism Series5 and other books for review in a journal founded by his father in 1919, Finanzpolitische Korrespondenz. He was also known to be in touch with Rajani Palme Dutt, the intellectual guru of the CPGB and editor of the British Communist journal Labour Monthly. He joined the KPD in July 1930 and following a visit to the Soviet Union later that year was appointed economics editor of the KPD’s newspaper Die Rote Fahne. From 1931 he was a fervent supporter of the Revolutionary Trade Union Opposition (RGO) in Germany and often attended official parties together with his father at the Soviet Embassy. He was a close friend of Erich Kunik, head of the information section of the KPD Central Committee who brought him into the KPD’s inner circle. On 24 June 1931 Frank Foley included Jürgen ‘in a list of functionaries of the Communist Central Organisations’ sent to MI5.

Toward the end of 1931 Jürgen was introduced to the Hungarian economist Eugen Varga, who was then working at the Comintern office in the Lindenstrasse, Berlin, and again visited the Soviet Union. He edited the book, Rote Arbeit: der neue Arbeiter in der Sowjetunion (Red Work: The New Worker in the Soviet Union) defending labour conditions in the Soviet Union against accusations by Western countries that inhumane and slave labour conditions were the norm. The book praised Stalin’s Five-Year Plan and extolled the efficiency and superiority of the Russian worker and workforce in the early 1930s compared with their Western counterparts during the Great Depression.6 Ronald Boswell, director of publishers John Lane, discussed publishing an English edition but the project was not completed. Rote Arbeit was, nevertheless, an impressive piece of propaganda for ‘Socialism in One Country’, welcoming the development of heavy industry and the collectivisation of agriculture as essential for the modernising of the Soviet economy.7 At the time the OGPU’s head of counter-intelligence, Artur Artuzov, was in charge of a major disinformation campaign known as ‘Operation Tarantella’, which aimed to convince the West that ‘the industrialisation of the Soviet Union was a huge success’.8 Artuzov, who was seeking to engage foreign correspondents as propaganda accomplices, had a high regard for Jürgen’s ability. Moscow Centre wanted London to believe that the Soviet Union was far stronger than it actually was. This was the message also carried by fellow-travelling foreign correspondents, among them Jürgen Kuczynski.9

Jürgen’s reputation as a writer was put to good use by the KPD and in 1932 he made the acquaintance of the German Communist propaganda genius, Willi Münzenberg.10 Later that year he attended the ‘World Congress against War’ held in Amsterdam on 27–29 August.11 Two thousand delegates from twenty-seven countries gathered from various workers’ groups, many of whom belonged to the Communist Parties or were known to be sympathetic towards Russia. Accordingly, debate centred upon the need to defend the Soviet Union from the reactionary policies of the Western imperialist powers, chiefly Great Britain. Fascism received little attention. However, at the closing session it was agreed to create a permanent body, the ‘World Committee against War and Fascism’ (WCAWF), with headquarters in Berlin, to co-ordinate the activities of all working-class parties and progressive groups opposed to the rise of Fascism and militarism. The success of the new body was undoubtedly due to Münzenberg. His skills as a publicist convinced many prominent non-Communist pacifists to join the Committee, among them Henri Barbusse, Romain Rolland, Albert Einstein, Heinrich Mann, Bertrand Russell, Havelock Ellis, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, and Upton Sinclair. Münzenberg’s success in bringing together a number of varied anti-Fascist organisations, however, unsettled the Stalinist-dominated Communist International, whose policy of ‘Class against Class’ adopted at the Sixth World Congress of the Comintern in 1928 had condemned any co-operation with social democracy. Consequently, in October 1932 control of the WCAWF passed from the charismatic architect of the fellow-traveller Münzenberg to the Bulgarian Stalinist Georgi Dimitrov, who would achieve worldwide fame for his defence against Nazi accusations during the German Reichstag Fire trial of 1933.

Three days after Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933, the Nazis dissolved the Reichstag and new elections were arranged for 5 March. The KPD, the largest Communist Party outside the Soviet Union with 360,000 members,12 adopted a policy of wait and see. To many observers it looked increasingly unlikely that the Nazis would obtain a simple majority even in conjunction with its nationalist allies. Then, on the night of 27 February, the Reichstag building went up in flames. One eyewitness described the spectacle:

We arrived at the scene perhaps half an hour after the show had been officially opened. The big cupola was bursting in flames like a volcano. The wide square in front of the building overflowed with SA men. Many of them for the first time flaunted their armbands as ‘Auxiliary Police’. The Berliners openly made fun of them: ‘They must have known in advance! They couldn’t have come here so fast with their bandy legs!’

Over the portals of the Reichstag there stood, hewn in stone, the inscription: ‘To the German People’. We saw these words, expression of parliamentary democracy, disappear in brownish clouds of smoke, then we left.13

The fire, ‘a highly imaginative act of provocation’, was used to ‘whip up a wave of panic and anti-Communist hysteria’, paving the way for presidential emergency legislation and a surprise attack on the KPD, leading to the arrest of its leading members throughout Germany.14 With parliamentary democracy in Germany literally succumbing to the flames, the KPD was forced underground or into exile. By the end of 1933, more than 130,000 Communists had been thrown into concentration camps and 2,500 murdered. Systematically destroyed as a mass movement, the direction of Party work in Germany was placed in the hands of a small group of seven or eight Politburo members with Walter Ulbricht,15 Franz Dahlem16 and Wilhelm Pieck17 emerging as the leading figures.

At the end of May 1933, it was decided that the continued presence of its members in Germany was far too dangerous and the Politburo divided itself into two sections: home leadership (Inlandsleitung) in Berlin and an external or émigré leadership (Auslandsleitung) with its base in Paris. By the autumn of 1933 the position of those in the Inlandsleitung was so precarious that it was decided that they too should emigrate and supervision of the underground work was passed to Czechoslovakia. From the autumn of 1933 onwards the entire leadership of the KPD was in emigration, divided between Paris and Prague.18 Münzenberg had fled to Paris where, following Dimitrov’s arrest by the Nazis in connection with the fire, he resumed the leadership of the WCAWF. Under his guidance, a major anti-war and anti-Fascist conference was held at the Salle Pleyel, Paris, in June 1933 with nearly 3,000 delegates in attendance. Münzenberg, meanwhile, had shifted his position. In a clear signal to Moscow, he moved away from the idea that there were no enemies on the Left. He did, however, criticise the Communists for their abuse of the fellow-traveller, which he regarded as counterproductive. At Salle Pleyel the united front was no longer regarded as heresy and an alliance of socialists and Communists created the ‘World Committee of Struggle against War and Fascism’ (WCSAWF), albeit with the Communists as the dominant partner. The Amsterdam-Pleyel movement, as the alliance was commonly known after 1933, began the construction of a Popular Front coalition19 in France and, to a lesser extent, in the UK; although it came much too late to heal the cleavages between the KPD and SPD in Germany and in emigration.

That same year Jürgen, who had remained in Berlin, was recruited to Soviet intelligence by Sergei Alekseevich Bessonov, provisional acting head of the second western department of the Narodnyi komissariat vnutrennekh del (NKVD),20 the predecessor of the KGB, and counsellor at the Soviet embassy in Berlin 1933–35.21 Jürgen regarded Bessonov as ‘the “perfect Communist” – educated, cultured, intelligent and a warm friend. He was interested in everything, to the extent that he could hold a half-hour conversation about the preparation of fish with Marguerite.’22 Once or twice a month he would meet secretly with Bessonov or with the Soviet Ambassador Lev Khinchuk and then his successor, Yakov Surits, submitting reports on the German situation.23

At the time Jürgen’s Berlin despatches were regarded so highly that they were sent directly to the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, Maxim Litvinov at Narkomindel (NKID).24 They were partly responsible for the siege mentality developing in the Soviet Union, with Surits confirming Germany’s hostility towards Communism and Hitler’s intention to bring about the international isolation of the USSR.25 Intelligence from Germany – that Hitler was seeking a rapprochement with the West in anticipation of a military crusade against the Soviet Union – led Stalin to seek an accommodation with Hitler. Throughout this period the Soviet Union pursued a two-tier foreign policy – official and unofficial, formal and informal – based on a policy of binding Germany to Russia in a continental bloc against Britain and France. Jürgen’s work with Bessonov and the Soviet Embassy in Berlin was very much within this two-tier framework. In 1935 he was invited to Moscow by the Soviet economist Eugen Varga who, under the name E. Pawlowski, had recently published a series of influential pamphlets encouraging Communist collusion with German nationalist elements:

The German worker will work for British and French imperialism under the control of German managers, who will share the profits with their foreign superiors. Thus Germany will be transformed into a colony of British and French imperialism, working as much as India or Indo-China for the profit of the City and the Bourse. Until now colonies have been backward agrarian countries with slight industrial development. The main profit of the British Empire comes from areas forced to accept British-manufactured commodities in exchange for raw materials and agrarian products. Germany will be the first of a new type of colony; its highly developed industry will be incorporated in its entirety into the British industrial system.26

While visiting Varga in Moscow, Jürgen established contact with two exiled members of the KPD leadership, Walter Ulbricht and Wilhelm Pieck. They impressed upon him the importance of the KPD maintaining its whole apparatus in exile in readiness to seize power following the downfall of the Nazi regime. He was advised to leave Germany and work with his family in the UK. By this time all the Kuczynskis were in London with the exception of Jürgen’s eldest sister, Ursula.