5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Lozzi Roma

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

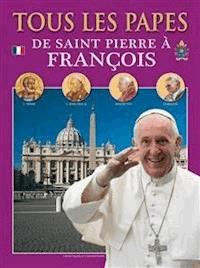

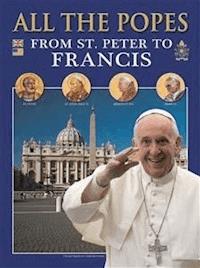

A book of biographies and images of every pope in the history of the Catholic Church, from Saint Peter to Francis. The volume is enriched with the coats of papal arms, a folding poster with medallion portraits of all the popes, and includes a chronological and alphabetical index.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

All the Popes

FROM SAINT PETER TO FRANCIS

Chronological List of the popes

“1 – Saint Peter (67)”

“2 – (Saint) Linus (67-76)”

“3 – (Saint) Anacletus (1st century)”

“4 – Saint Clement I (88-97)”

“5 – Saint Evaristus (97-105)”

“6 – Saint Alexander I (105-115)”

“7 – (Saint) Sixtus I (115-125)”

“8 – (Saint) Telesphorus (125-136)”

“9 – (Saint) Hyginus (136-140)”

“10 – Saint Pius I (140-155)”

“11 – (Saint) Anicetus (155-166)”

“12 – (Saint) Soter (166-175)”

“13 – Saint Eleutherius (175-189)”

“14 - Saint Victor I (189-199)”

“15 – Saint Zephyrinus (199-217)”

“16 - Saint Callistus I (217-222)”

“17 – Saint Urban I (222-230)”

“18 – Saint Pontian (230-236)”

“19 – Saint Anterus (235-236)”

“20 – Saint Fabian (236-250)”

“21 – Saint Cornelius (251-253)”

“22 – (Saint) Lucius I (253-254)”

“23 – Saint Stephen I (254-257)”

“24 – Saint Sixtus II (257-258)”

“25 – Saint Dionysius (259-268)”

“26 – Saint Felix I (269-274)”

“27 – Saint Eutychian (275-283)”

“28 - (Saint) Caius or Gaius (283-296)”

“29 – Saint Marcellinus (296-304)”

“30 – Saint Marcellus I (308-309)”

“31 – Saint Eusebius (309)”

“32 – (Saint) Miltiades (311-314)”

“33 – Saint Sylvester I (314-335)”

“34 – Saint Mark (336)”

“35 – Saint Julius I (337-352)”

“36 – Liberius (352-366)”

“37 – Saint Damasus I (366-384)”

“38 – Saint Siricius (384-399)”

“39 – Saint Anastasius I (399-401)”

“40 – Saint Innocent I (401-417)”

“41 – Saint Zosimas (417-418)”

“42 – Saint Boniface I (418-422)”

“43 – Saint Celestine I (422-432)”

“44 – (Saint) Sixtus III (432-440)”

“45 – Saint Leo I (the Great) (440-461)”

“46 – Saint Hilarius (461-468)”

“47 – Saint Simplicius (468-483)”

“48 - Saint Felix III (483-492)”

“49 – Saint Gelasius I (492-496)”

“50 – (Saint) Anastasius II (496-498)”

“51 – Saint Symmachus (498-514)”

“52 – Saint Hormsidas (514-523)”

“53 – Saint John I (523-526)”

“54 – Saint Felix IV (526-530)”

“55 – Saint Boniface II (530-532)”

“56 – John II (533-535)”

“57 – Saint Agapetus I (535-536)”

“58 – Saint Silverius (536-537)”

“59 – Vigilius (537-555)”

“60 - Pelagius I (556-561)”

“61 – John III (561-574)”

“62 – Benedict I (575-579)”

“63 – Pelagius II (579-590)”

“64 – Saint Gregory I the Great (590-604)”

“65 – Sabinian (604-606)”

“66 – Boniface III (607-607)”

“67 – Boniface IV (608-615)”

“68 – Saint Adeodatus I or Deusdedit (615-618)”

“69 – Boniface V (619-625)”

“70 – Honorius I (625-638)”

“71 – Severinus (640)”

“72 – John IV (640-642)”

“73 – Theodore I (642-649)”

“74 – Saint Martin I (649-655)”

“75 – Saint Eugene I (654-657)”

“76 – Saint Vitalian (657-672)”

“77 – Adeodatus II (672-676)”

“78 – Donus (676-678)”

“79 – Saint Agatho (678-681)”

“80 – Saint Leo II (682-683)”

“81 – Saint Benedict II (684-685)”

“82 – John V (685-686)”

“83 – Conon (686-687)”

“84 - Saint Sergius I (687-701)”

“85 – John VI (701-705)”

“86 – John VII (705-707)”

“87 – Sisinnius (January 15-February 4, 708)”

“88- Constantine (708-715)”

“89 – Saint Gregory II (715-731)”

“90 – Saint Gregory III (731-741)”

“91 – Saint Zachary (741-752)”

“92 – Stephen II (III) (752-757)”

“93 – Saint Paul I (757-767)”

“94 – Stephen III (IV) (768-772)”

“95 – Adrian I (772-795)”

“96 – Saint Leo III (795-816)”

“97 – Stephen IV (V) (816-817)”

“98 – Saint Paschal I (817-824)”

“99 – Eugene II (824-827)”

“100 - Valentine (August-September 827)”

“101 – Gregory IV (827-844)”

“102 – Sergius II ( 844-847)”

“103 – Saint Leo IV (847-855)”

“104 – Benedict III (855-858)”

“105 – Saint Nicholas I (858-867)”

“106 - Adrian II (867-872)”

“107 – John VIII (872-882)”

“108 – Marinus I (882-884)”

“109 – Saint Adrian III (884-885)”

“110 – Stephen V (VI) (885-891)”

“111 – Formosus (891-869)”

“112 – Boniface VI (896)”

“113 – Stephen VI (VII) (896-897)”

“114 – Romanus (August-November 897)”

“115 –Theodore II (897)”

“116 – John IX (898-900)”

“117 – Benedict IV (900-903)”

“118 – Leo V (July-September 903)”

“119 – Sergius III (904-911)”

“120 – Anastasius III (911-913)”

“121 – Lando (913-914)”

“122 – John X (914-928)”

“123 – Leo VI (May-December 928)”

“124 - Stephen VII (VIII) (928-931)”

“125 – John XI (931-935)”

“126 – Leo VII (936-939)”

“127 – Stephen VIII (939-942)”

“128 – Marinus II (942-946)”

“129 – Agapetus II (946-955)”

“130 – John XII (955-964)”

“131 – Leo VIII (963-965)”

“132 – Benedict V (964-966)”

“133 – John XIII (965-972)”

“134 – Benedict VI (973-974)”

“135 – Benedict VII (974-983)”

“136 – John XIV (983-984)”

“137 – John XV (985-996)”

“138 – Gregory V (996-999)”

“139 – Sylvester II (999-1003)”

“140 – John XVII (1003)”

“141 – John XVIII (1004-1009)”

“142 – Sergius IV (1009-1012)”

“143 – Benedict VIII (1012-1024)”

“144 – John XIX (1024-1032)”

“145/147/150 – Benedict IX (1032 -1048)”

“146 – Sylvester III (January 20-February 10, 1045)”

“148 – Gregory VI (1045-1046)”

“149 – Clement II (1046-1047)”

“151 – Damasus II (1048)”

“152 – Saint Leo IX (1049-1054)”

“153 – Victor II (1055-1057)”

“154 – Stephen IX (X) (1057-1058)”

“155 – Nicholas II (1059-1061)”

“156 – Alexander II (1061-1073)”

“157 – Saint Gregory VII (1073-1085)”

“158 – Blessed Victor III (1086-1087)”

“159 – Blessed Urban II (1088-1099)”

“160 – Paschal II (1099-1118)”

“161 – Gelasius II (1118-1119)”

“162 – Callistus II (1119-1124)”

“163 – Honorius II (1124-1130)”

“164 – Innocent II (1130-1143)”

“165 – Celestine II (1143-1144)”

“166 – Lucius II (1144-1145)”

“167 – Blessed Eugene III (1145-1153)”

“168 – Anastasius IV (1153-1154)”

“169 – Adrian IV (1154-1159)”

“170 – Alexander III (1159-1181)”

“171 – Lucius III (1181-1185)”

“172 – Urban III (1185-87)”

“173 – Gregory VIII (25 October-17 December 1187)”

“174 – Clement III (1187-1191)”

“175 – Celestine III (1191-1198)”

“176 – Innocent III (1198-1216)”

“177 - Honorius III (1216-1227)”

“178 - Blessed Gregory IX (1227-1241)”

“179 - Celestine IV (28 October-10 November 1241)”

“180 - Innocent IV (1243-1254)”

“181 - Alexander IV (1254-1261)”

“182 - Urban IV (1261-1264)”

“183 - Clement IV (1265-1268)”

“184 - Blessed Gregory X (1271-1276)”

“185 - Blessed Innocent V (21 January-22 June 1276)”

“186 - Adrian V (11 July-18 August 1276)”

“187 - John XXI (1276-1277)”

“188 - Nicholas III (1277-1280)”

“189 - Martin IV (1281-1285)”

“190 - Honorius IV (1285-1287)”

“191 - Nicholas IV (1288-1292)”

“192 - Saint Celestine V (5 July-13 December 1294)”

“193 - Boniface VIII (1294-1303)”

“194 - Blessed Benedict XI (1303-1304)”

“195 - Clement V (1305-1314)”

“196 - John XXII (1316-1334)”

“197 - Benedict XII (1334-1342)”

“198 - Clement VI (1342-1352)”

“199 - Innocent VI (1352-1362)”

“200 - Blessed Urban V (1362-1370)”

“201 - Gregory XI (1370-1378)”

“202 - Urban VI (1378-1389)”

“203 - Boniface IX (1389-1404)”

“204 - Innocent VII (1404-1406)”

“205 - Gregory XII (1406-1415)”

“206 - Martin V (1417-1431)”

“207 - Eugene IV (1431-1447)”

“208 - Nicholas V (1447-1455)”

“209 - Callistus III (1455-1458)”

“210 - Pius II (1458-1464)”

“211 - Paul II (1464-1471)”

“212 - Sixtus IV (1471-1484)”

“213 - Innocent VIII (1484-1492)”

“214 - Alexander VI (1492-1503)”

“215 - Pius III (22 September-18 October 1503)”

“216 - Julius II (1503-1513)”

“217 - Leo X (1513-1521)”

“218 - Adrian VI (1522-1523)”

“219 - Clement VII (1523-1534)”

“220 - Paul III (1534-1549)”

“221 - Julius III (1550-1555)”

“222 - Marcellus II (9 April- 1 May 1555)”

“223 - Paul IV (1555-1559)”

“224 - Pius IV (1559-1565)”

“225 - Saint Pius V (1566-1572)”

“226 - Gregory XIII (1572-1585)”

“227 - Sixtus V (1585 1590)”

“228 - Urban VII (15-27 September 1590)”

“229 - Gregory XIV (1590-1591)”

“230 - Innocent IX (29 October-30 December 1591)”

“231 - Clement VIII (1592-1605)”

“232 - Leo XI (1-27 April 1605)”

“233 - Paul V (1605-1621)”

“234 - Gregory XV (1621-1623)”

“235 - Urban VIII (1623-1644)”

“236 - Innocent X (1644-1655)”

“237 - Alexander VII (1655-1667)”

“238 - Clement IX (1667-1669)”

“239 - Clement X (1670-1676)”

“240 - Blessed Innocent XI (1676-1689)”

“241 - Alexander VIII (1689-1691)”

“242 - Innocent XII (1691-1700)”

“243 - Clement XI (1700-1721)”

“244 - Innocent XIII (1721-1724)”

“245 - Benedict XIII (1724-1730)”

“246 - Clement XII (1730-1740)”

“247 - Benedict XIV (1740-1758)”

“248 - Clement XIII (1758-1769)”

“249 - Clement XIV (1769-1774)”

“250 - Pius VI (1775-1799)”

“251 - Pius VII (1800-1823)”

“252 - Leo XII (182 3-1829)”

“253 - Pius VIII (1829-1830)”

“254 - Gregory XVI (1831-1846)”

“255 - Blessed Pius IX (1846-1878)”

“256 - Leo XIII (187 8-1903)”

“257 - Saint. Pius X (1903-1914)”

“258 - Benedict XV (1914-1922)”

“259 - Pius XI (1922-1939)”

“260 - Pius XII (1939-1958)”

“261 - Saint John XXIII (1958-1963)”

“262 - Paul VI (1963-1978)”

“263 - John Paul I (26 August-28 September 1978)”

“264 - Saint John Paul II (16 October 1978-2 April 2005)”

“265 - Benedict XVI (April 19, 2005-February 28, 2013, by abdication)”

“266 - Francis (13 March 2013)”

INTRODUCTION

The word Pope derives from the ancient Greek word pàppas (father) which refers to the spiritual paternity of bishops. The term was first used in the Orient, it was not used in the West until the first half of the 5th century. It was affirmed definitively in the 8th century as the official title for the Bishop of Rome, the successor of the Apostle Peter. In the hierarchy of the church, the word pontiff has the same meaning.

Since 1059, the election of the Pope has been entrusted exclusively to the Church cardinals to limit interference from external political influences. The figure of universality prevails definitively on the Rome Bishop and reinforces the role of monarch. Since the first half of the 13th century the Pope has defined the doctrinal development of concepts such as the vicarious cristi, which is the foundation for the belief that the Pope, with his sacred investiture, is above humanity. The First Vatican Council (1870) deemed the Pope infallible in a moral and doctrinal sense, with the definition ex cathedra.

The new “Universal Church Calendar” no longer lists all of the first 54 popes as saints; for clarity and respect of the timeworn tradition which considered them so, the title (Saint) is written in parenthesis for the popes that are no longer considered as such.

The mosaic medallion icons are reproductions of the busts of the popes, which can be found on Via Ostiense at the Basilica of Saint Paul’s Outside the Walls in Rome. Each circle, reproduced on models by the Vatican School, is 1.90 meters in diameter with a frame of gilded bronze.

The habit of adopting a Pontifical Stem was introduced by Pope Innocent III and has continued without interruption. Generally, popes with nobile origins used their family stem. The tradition continues today and even popes without nobile origins have adopted a sSem, usually based on a personal choice or particular devotion (such as the Virgin Mary on the papal Stem of John Paul II). It is usually used on all official documents signed by the Sainted Father including enclyclicals, papal bulls, as well as works.

For chronologically ordering the 266 Pontifical Heads of the Church, we scrupulously followed the Annuals of the Vatican Pontificate. For further clarification, take note that of the 266 popes considered (264 to be exact, because Benedict IX was elected three times during the tremendous battles between popes and antipopes during the medieval period). Of all the popes, 207 are Italian and 106 are Roman. The number of antipopes has been definitively set at 37. With the term antipope, we intend an antagonist elected irregularly alongside the legitimate Pope.

There have been 57 non-Italian popes, of the following nationalities: 19 French, 14 Greek, 8 Syrian, 6 German, 3 African, 2 Spanish, 1 Austrian, 1 Portuguese, 1 Palestinian, 1 English, 1 Dutch, 1 Polish and 1 Argentine Pope.

A Short History of the Papacy

The title “Pope” was originally bestowed on all bishops, but since the 5th century it has been reserved exclusively for the Bishop of Rome. In the Roman Catholic Church, the Pope has the power of divine institution, because he is the Vicar of Christ and the successor of Saint Peter to whom Christ entrusted the duty of perpetuating his Word “until the end of time.”

The authority of the Bishop of Rome was affirmed between the 1st and 4th century. The first known Pontifical Act dates back to the year 96 and was issued by Saint Clement to the Christian community in Corinth. In the 2nd century the Bishop of Carthage, Saint Cyprian, defined the Roman Church as “the central Church from which the unity of the clergy springs.” More explicit acknowledgement of Christianity’s diffusion throughout the Roman Empire came about with the edict of Milan (313), issued by Emperor Constantine, allowing Christians religious freedom and restoring possessions that had been confiscated from them. Furthermore, the Emperor, for religious vocation and to stabilise the empire, took an active role in ecclesiastical organisation. He nominated bishops in many major cities and is responsible for the construction of several Basilicas, including the ancient Saint Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican. He is also credited with calling the Nicene Council (325), the first of 22 Ecumenical councils. At the event, 220 bishops reunited and drew up the Nicene Creed or symbol, outlining Christian doctrine.

Under the reigns of Constantine and Theodosius (who proclaimed Christianity as the state religion) the temporal power of the Church grew, thanks to gifts from wealthy followers. Saint Sergius affirmed in 385 that the law of the Roman Church was valid everywhere, while the Council of Calcedonia (451) affirmed that “Peter hath spoken by the mouth of the Pope”.

At the fall of the Roman Empire in 476, the papacy remained the only power capable of defending the Italian peninsula from the invading barbarians. The pontificate of Saint Leo the Great (440-461) and Saint Gregory the Great (590-604) strengthened the relationship with the new rulers and began the work of spreading Christianity throughout Europe.

Longobard King Liutprando donated Sutri (north of Rome) in 728, to the Church marking the beginnings of the Pontifical State. In the year 755, French King Pepin the Short made ulterior donations following his march into the Italian peninsula to defend Pope Stephen II during the Longobard invasion. French influence reached its apex during the year 800 when Charlemagne was crowned Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire by Pope Saint Leo III.

The decay of the Carolignian Empire (903) and the rise of feudalism weakened the Church immensely. Rome lived through years of siege and battle, which inevitably took its toll on papal power; the period was characterised by weak popes who were at the mercy of stronger factions.

Leo IX presided over The council of Reims in 1049, declaring the Rome Bishop as the First Apostle of the universal Church. The Empire’s dominance over the Church waned with Nicholas II. He restored the cardinals’ right to elect the Pope in 1059. With the famous humiliation of Emperor Henry IV at Canossa (1077) and the edict of Worms (1122) the papacy gained a dominant role in the exercise of spiritual power throughout Europe. Pope Gregory VII (1073-1085) affirmed papal supremacy with his document Dictatus Papae, securing the pontifical right to dismiss the emperor. In the 13th century, Pope Innocent III elaborated the theory of “papal theocracy,” awarding the Pope spiritual and temporal power. Emperors, whose powers descended directly by divine will, still did not have enough strength to rule without investiture from the Roman Church. The Pope required an act of obedience from nominated bishops and his delegates were present in churches throughout the European continent to ensure that his decrees were carried out.

The crusades, which began in 1095 under the reign of Urban II, fit perfectly in this context. With Islam occupying the Holy Land, the kingdom united under the symbol of the Holy Cross fighting against a common enemy, which kept feudal contrasts under control.

At the end of the 13th century, the birth of national States (France and England first) and monarchical absolutism, threatened the unity of the Holy Roman Empire and cut deeply into the foundations of pontifical power. French Pope Clement V was pressured by the King of France in 1309 to move the pontifical seat to the city of Avignon in Provence, beginning the “Avignon captivity,” which lasted until 1377. During this time the popes were under the tutelage of the King of France. This was followed by the clamorous era of the great Western schism (1378-1417) when two and three popes simultaneously sought the pontifical throne, bringing about heretical and schismatic currents in central Europe.

During the Renaissance (the second half of the 15th century), the Church neglected its spiritual and doctrinal role and fell into merely exercising power. The Pope’s hegemonic power ebbed and local discontentment grew, bringing about the rebellion of Luther and Calvin in 1517, which blossomed into the Protestant Reformation. Paul III tried to halt the disintegration of Europe, in 1545, with the council of Trent, which lasted, with various interruptions, until 1563. This resulted in strengthening the papacy and brought about the founding of governing organisations such as the Sant’Uffizio, the Index and new congregations.

During the 17th and 18th century, the curia became very Italian and only Italian popes were nominated until 1978. The affirmation of the large European states brought about a drastic reduction of Papal power, even in Catholic countries.

The French Revolution, in 1789, caught the Sainted Seat completely unprepared to affront the far-reaching issues it caused. Napoleon’s imperial ambitions partially restored the Church’s political role, in 1804, when the Pope crowned him emperor in Notre Dame. The French conquest of Rome in 1809 and the arrest of Pope Pious VII brought about a long period of pontifical detention that would last until 1813.

After the Vienna Congress (1814-1815), the restoration following Napoleon’s reign restored temporal power to the Roman Church and the pontifical state (which extended throughout central Italy) and confirmed the role of spiritual leader to the main governing nobility of Europe. However in the 18th century, the difficulty of managing these two roles kept the Pope from truly understanding the Risorgimento that pervaded the Italian peninsula as well as the central Catholic Hapsburg Empire. The encyclicals published by Gregory XVI and Pius IX against the liberal ideas of the times were written in this context.

The disbanding of the Pontifical State (1870) following the unity of Italy caused the difficult “Roman question” between the Pope and the kingdom of Italy, bringing about the end of the pontificate’s temporal power. The voluntary exile of Pius IX, in the Vatican, reshaped the role of the Church in Italy and world politics and limited its power to the sphere of religious doctrine. From that came the first Vatican council’s (1870) proclamation of the dogma of papal infallibility and the encyclicals by Leo XIII and Pius X.

Pope Benedict XV (1914-1922) tried, without luck, to convince international communities to desist with the “useless destruction” of the World War I. He did however lay the foundations for the pacifistic policy that has characterised the Church throughout the 20th century.

Pope Pius XI (1922-1939) reached an agreement with the Italian government, led by Mussolini, with the Lateran Pacts (1929), which gave the Church dominion over Vatican City (44 hectares inside the city of Rome) as well as acknowledging Church autonomy in ecclesiastical organisations throughout the Italian territory. World War II and the difficult times following it characterised the pontificate of Pius XII (1939-1958), who wisely opposed the totalitarian, Nazi and Fascist regimes and was a strong enemy of Soviet Russia. He provided the faithful with conservative doctrine to oppose the rapid changes in world society after the war. Pope John XXIII understood that the Church, in order to maintain an important role in society, had to modernise and to change its institutions to fit the necessities of the modern world. After three years of preparation, in 1962 he called the second Vatican council, which would be continued by Paul VI, and which, left a strong mark on Catholic history, determining the organisation of ecclesiastical structures and the fundamental doctrines that characterise today’s Church. In 1978, after the short pontificate of John Paul I (August-September), the conclave of cardinals elected Polish Cardinal Karol Wojtyla as Pope. He took the name John Paul II and during his 27-year pontificate, restored the papacy’s importance in political and social issues, accelerating the fall of soviet communism and changing the world’s political geography. Following the outline of second Vatican council, Pope Wojtyla fixed several points of religious doctrine and reinforced the Catholic world community’s bonds with the Sainted Seat, opening dialogue with other religions, and fighting to stop political conflicts from turning into religious wars.

In April 2005, following the trend, another non-Italian Pope was elected. The German Cardinal Ratzinger, took the name Benedict XVI as Pope. The Pope, during his eight years of pontificate, has noted with dismay a “Church with a disfigured, scarred, torn face, due to the errors of its children, from the simple faithful to the bishops and cardinals”. He has also fought, with courage and determination, for the recognition of religious freedom in the world. On 11 February 2013, during the Consistory, Benedict XVI announced his historic and moving resignation: his abdication from “the ministry of the Bishop of Rome, successor of St. Peter, entrusted to me by the hand of the Cardinals April 19, 2005”. On 28 February 2013, Benedict XVI left the Vatican by helicopter and moved temporarily into the papal summer residence of Castel Gandolfo.

On the evening of 13 March 2013, on the fifth ballot, Jorge Mario Bergoglio was elected Pope and took the name of Francis in honour of St. Francis of Assisi.

Peter’s 266th successor, he presents himself as a humble shepherd, capable of looking at a universal Church that spreads “the announcement of God’s love and mercy” everywhere, bringing his style as an energetic and capable Bishop and preacher to the Vatican.

1 – Saint Peter (67)

He was born in Betsaida. After the Resurrection, on Lake Tiberiade, Christ entrusted his flock, to Peter, consecrating him as pontiff. One of the Twelve Apostles, his name was originally Simon, but was changed by Jesus to Kefa, meaning “rock.” Peter was the first of the disciples to whom the Messiah appeared after his resurrection and the first to perform a miracle. He is accredited with the first ecclesiastic ordination, thus he is considered the founder of the Holy Roman Church. Arrested and martyred during Nero’s reign, he was crucified head down. He died on June 29, 67 and was buried on Vatican hill, where the Basilica of Saint Peter’s now stands.

2 – (Saint) Linus (67-76)

Born in Volterra (in the Italian province of Pisa), there is not much information about his life. He was made Pope in 67 and lived through the reigns of five different emperors: Nero, Galba, Otone, Vitellius, and Vespasian. During his pontificate, the Evangelists Mark and Luke were martyred. He is attributed with issuing a decree requiring women to cover their heads when entering sacred places and during religious functions. During this era, the heresies of the Cerinians and the Gnostics took place. Linus was martyred during the reign of Vespasian and was buried next to Saint Peter.

3 – (Saint) Anacletus (1st century)

He was born in Athens. The precise dates are unknown, but presumably his pontificate lasted from 77 until 88. During that time, Emperor Domitian relentlessly persecuted the Christians because they did not want to contribute to restoring the Temple of Jupiter.

Anacletus instituted the first parochial divisions in Rome, separating the city into 25 zones, each directed by a different priest. He was martyred after having a temple built on Saint Peter’s tomb, destined as a resting place for martyrs, this is where he was later buried.

4 – Saint Clement I (88-97)

Born in Rome, he was Peter and Paul’s disciple. Martyred during the reign of Emperor Trajan, he was exiled to Turkey and condemned to forced labor. After refusing to make a sacrifice to the gods, in 97, Clement was punished with an atrocious death: he was thrown into the sea with an anchor tied around his neck.

Several written works are attributed to him, nearly all of them are considered apocryphal, except for his “First letter to the Corinthians,” which was written in Greek. He is buried in Rome in the Church that carries his name.

5 – Saint Evaristus (97-105)

Originally from Judea, the fourth successor of Peter was elected during the reign of Emperor Trajan. There is not a lot known about his life. It is said that he instituted parochial districts to accommodate the growing numbers of faithful and that he divided the city into diaconates. Each area was entrusted to an older priest, who supervised the diffusion of Christian aid and charity, giving rise to the present day cardinals. The circumstances of his death are unsure, and it is not clear if he was martyred. Neapolitan legend holds that he is buried in Naples in the Church of Saint Mary Major.

6 – Saint Alexander I (105-115)

Born in Rome, he was a disciple of Plutarch, and the first Pope to be elected by selection of the bishops in Rome instead of the Last Will and Testament of his predecessor. The third persecution by Emperor Trajan took place during his pontificate.

He is accredited with beginning the tradition of keeping holy water in churches and houses. Alexander was also responsible for the ruling that consecrated communion be made exclusively from unleavened bread. He was probably buried in the Roman Church Santa Sabina.

7 – (Saint) Sixtus I (115-125)

Of Roman origin, he was elected Pope during the reign of Emperor Hadrian, who had a tolerant attitude towards the Christians; Sixtus fought against the Gnostic heresy. He issued many liturgical and disciplinary decrees, such as the provision that the chalice and the paten can only touched by a priest. Pope Sixtus I is also responsible for the introduction of the brief liturgical inno, “Sanctus,” into the Holy Mass. Probably martyred, it is likely that his sepulchre is in the Cathedral of Alatri and not in the Vatican, which was previously believed to be his final resting place.