Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

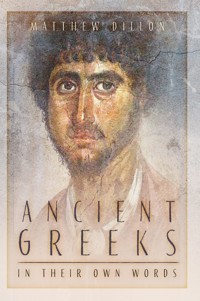

In Ancient Greeks in their own Words, historian Matthew Dillon reveals the nature of everyday life in the classical world. Using a series of telling extracts from Greek literature to provide a picture of their customs, concerns and underlying values, he allows the people to speak for themselves, both in the formal language of public office and in the colloquial speech of the household and the street. Their words reveal activities and opinions which are sometimes remarkably similar to those of the modern day, but which are otherwise so different that they are difficult for us to understand. Through everything from poetry, hymns and war-songs to official documents, inscriptions, laws, histories, funerary monuments, war memorials and graffiti, this book records not only the lives of famous Greeks like Sophocles and Aristotle, but also those of ordinary individuals. In Ancient Greeks in their own Words, glimpse the public and private facets of their everyday life, and gain an insight into the mentality of the ancient Greeks.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 593

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Front cover illustration: agis / Alamy Stock Photo

First published 2002

This paperback edition first published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Matthew Dillon, 2002, 2024

The right of Matthew Dillon to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 874 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

Contents

Preface

Introduction

ONE

Gods and Mortals

TWO

Husbands and Wives

THREE

Farmers and Traders

FOUR

Workers and Entertainers

FIVE

Soldiers and Cowards

SIX

Philosophers and Doctors

SEVEN

Citizens and Officials

The Authors Themselves

Glossary

Suggested Reading

Preface

I would like to thank Rupert Harding of Sutton Publishing for first inviting me to write this book. I hope his original aim of providing a series of extracts at once both interesting and informative about the ancient Greeks is met by this volume. The editors at Sutton have been most patient while this volume has been delayed by ever-increasing teaching duties.

Not every aspect of the ancient Greeks or ancient Greece is covered by the passages translated here, but I hope that they give enough information to provide at least a broad overview of the main features of Greek society and the sorts of things that the Greeks themselves considered important. This is in no sense a political history but aims to reveal something about the nature and characteristics of the Greeks themselves.

The passages translated are chosen mainly from well-known authors in order to encourage readers towards further exploration in the main works of Greek literature. I have tried to keep the translations as close as possible to the original Greek but I have not hesitated to modify them for sense when this is required. The process of selecting extracts is difficult from a corpus of writings numbering in the hundreds of thousands of words. If the choice seems idiosyncratic and eclectic, then this is the responsibility of the author. Comments on the passages are kept to a minimum, as I wanted the Greeks to speak ‘in their own words’.

I have translated poetry as poetry to help convey the ‘flavour’ of the text. Sometimes this means that the line numbering does not exactly correspond with the original, as some re-ordering of words and phrases is necessary for a smooth translation, but on the whole the line numbering matches that of the original texts. In rendering Greek names into English I have largely used traditional forms, such as Achilles rather than the exact transliteration Achilleus, which I think will be more familiar to the reader. Some names, however, are closer to the original, but I have usually aimed to make them recognisable rather than alien. Perhaps this volume will encourage some readers to commence the study of the ancient Greek language.

I need (again) to thank my wife for taking time out of her own heavy academic duties to proofread this volume. Thankfully we both share a love for ancient Greece. For my daughter Sophia who asks, ‘Haven’t you finished that book yet?’, and my son Isaiah who comes into the study and lays out my Greek texts on the floor to make ‘roads’, much love.

Matthew DillonArmidale, Australia, February 2002

Introduction

Man is but the dream of a shadow.

Pindar, Pythian Victory Ode, 8.95–6.

Pindar immediately arrests our attention here, drawing us towards a consideration of the ancient Greeks, and in a few words beckoning us towards their contemplation of the human spirit and its potential. Materially their temples are able even in their ruined state to speak to us about their religious aspirations. But their words reveal much more, defining the human spirit and speaking eternal truths.

Ancient Greece was the crucible of western civilisation. Most of what is known about the ancient Greeks comes from their writings, particularly in the archaic and classical periods, which lasted from about 800 BC to 336 BC. Archaeology is important, particularly when it yields the remains of houses, domestic items, works of art, graves and inscriptions. But on the whole it is writers such as Herodotus, Thucydides and Xenophon who provide the history of this period, with poets such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Pindar and Bacchylides revealing the ethos and customs of the Greeks.

Many of these writers were conscious of their own abilities. Thucydides wrote that his work was destined for posterity, to last for all time, while Pindar says of himself, Fragment 152: ‘My voice is sweeter than honey-combs toiled over by bees.’ There can be no better way to learn about the Greeks than by reading what they wrote about themselves: what concerned them most, what behaviour they found acceptable (and what unacceptable), what interested them, what they feared and what pre-occupied them.

But who were the ancient Greeks? Ancient Greece consisted of the Greek mainland itself, as well as Crete and the Aegean islands, just as it does today. But in addition the Greeks had in two main waves of colonisation spread elsewhere. From about 1200 to 1000 BC, the Greeks settled the coast of what is now Turkey, giving rise to magnificent cities such as Miletus, Ephesus and Didyma; the remains of these and other Greek cities are particularly impressive. There was a second wave of colonisation from about 800 to 600 BC when the Greeks settled the shores of the Black Sea, Sicily and southern Italy, with some colonies as far away as modern-day France (notably modern Marseilles) and Cyrene in Libya.

But like all societies, there were radical differences between not just various groups of Greeks but also between those living within the same city. The Greeks were not a homogenous group but lived in thousands of different communities, each recognisably Greek but also with local customs and other distinguishing features. Today, the remains of Greek temples from Naples in Italy to Ephesus in Turkey bear witness to this greater Greek world. But more than ruins are left behind. The Greeks produced the first outpouring of western literature, beginning with the poet Homer, the favourite of the Greeks themselves throughout their history. (In fact, over twenty Greek cities claimed to be his birthplace.) He and other poets believed that their works were the result of divine inspiration by the nine Muses, goddesses of poetic inspiration. The words of the Greeks included in this volume come not just from Greeks in Athens, but from those who lived in Asia Minor, on the Aegean islands, in Syracuse and Egypt. Over a cultural world several thousands of kilometres wide, they give voice to all that was best – and worst – in Greek civilisation.

Greece itself is often described as a country dominated by hills, mountains and small plains and this is true to some degree, but there is fertile soil. Thucydides wrote of the various waves of invasion of Greece, in which the best land was conquered by newcomers. Thucydides, 1.2.3, 5: ‘[1.2.3] It was always the best land that experienced changes of inhabitants, the land now called Thessaly and Boeotia, and most of the Peloponnese, except for Arcadia, and the most fertile areas of the rest of Greece . . . [1.2.5] But the area around Athens from the earliest times, because of its thinness of soil, was undisturbed and always inhabited by the same race of men.’ Sparta itself nestles in a bowl, and the snow of Mount Taygetus is visible from nearly any direction. Homer describes it in the Odyssey, 4.1: ‘Sparta lying in a hollow, full of ravines’.

In mainland Greece there are numerous mountain ranges often hemming in small or medium-sized plains. In the middle of such a plain, usually clustered around a hilly outcrop of rock, was the city. Many cities had such a centre and the Greeks called it an acropolis, of which that at Athens is an excellent example. On it stands the temple of the Parthenon, dedicated to the virgin goddess Athena; it still dominates the modern city’s skyline. And, as at Athens, the acropolis of an area was often the first place of settlement, and then as towns and cities grew, the people lived in houses clustered around its base and the acropolis became public property, where temples were built and often political meetings were held.

Ancient Greece was dominated by what is called the city-state, which the Greeks called the polis. Greece was not in any sense a ‘nation’, but rather a cultural phenomenon, something like the western European world, where there are separate governments that, however, share a common religious, political and economic heritage. The modern political building-block is the nation. In ancient Greece, its equivalent was the city-state. The polis was a small city by modern standards. There were literally hundreds of Greek cities, some of them no more than small towns. Greek city-states had their own armies, calendars, currencies and local variations on the main political systems of democracy, aristocracy or oligarchy. Different cities had different names for the months and common dating was non-existent.

Athens, with its 30,000 male citizens, was the largest Greek city-state, followed by Syracuse in Sicily, which had about 20,000 citizens. A city-state was ideally, in Greek eyes, an autonomous political unit. The city with its associated amenities was the high-point of Greek civilisation, and for the Greeks life without the city was unimaginable. Athens and Sparta were the main cities of ancient Greece, but there were many differences between them, not just physically but also in terms of temperament, characteristics and outlook.

At the conference of Sparta and its allies in 432 BC when it was debated whether to go to war or not against the Athenians, the delegates from Corinth attempted to goad the Spartans into action by unfavourably comparing them with the Athenians. The contrasts might be overdrawn but hold true on the whole: the Athenians were dynamic and resourceful, the Spartans (who never numbered more than 10,000, and this figure gradually decreased) tried to stay at home as much as possible and did not take risks, as they had a large servile population, the helots, to control. In their speech at Sparta, the Corinthians made the following points. Thucydides, 1.70.1–9:

(1.70.1) You Spartans have never considered what sort of men the Athenians are and how completely different from you are the men you will fight against. (1.70.2) They are without a doubt innovators, and quick to make their plans and to accomplish in reality what they have thought out, but you preserve simply what you have, and come up with nothing new, and in what you actually undertake don’t complete what has to be done. (1.70.3) And in addition, the Athenians are reckless beyond their capabilities, risking danger beyond their judgement, and are confident even in crises. But for you it is the case that you undertake less than your power allows, you distrust what your judgement is certain of, and think you will never escape from your crises. (1.70.4) And again, they are unhesitating while you procrastinate, they are abroad while you are the greatest ‘stay-at-homes’. They believe that by being abroad they will gain something, while you think that if you go out on campaign you will damage what you have already. (1.70.5) If they are victorious over their enemies they advance over the greatest distance, and when they are defeated give ground as little as possible.

(1.70.6) Furthermore, they use their bodies on behalf of the city as if they were somebody else’s, but their minds as most intimately their own for activities on her behalf. (1.70.7) And when they plan something but fail to achieve it they feel they have been robbed of their rightful possessions, and whenever they go after something and take possession of it, they consider they have achieved only a small thing compared with what the future will bring, and if they might fail in an undertaking, they make up for the loss by forming expectations for other things. For to them alone, having is the same as hoping in whatever they plan, due to the quickness with which they act upon their decisions. (1.70.8) At all this they labour with toils and dangers throughout their lives, and have little enjoyment of what they have as they are always acquiring more and they consider that there is no holiday except to do what has to be done, and that untroubled peace is no less a disaster than laborious activity. So if someone summing up the Athenians were to say that they were born neither to have peace themselves nor to allow it to other men, he would speak correctly.

So Athenian and Spartan characteristics were very different. In addition, the Athenians were wealthy and adorned their city with magnificent temples, such as the Parthenon mentioned above. Sparta, however, was lacking in financial resources and the modern visitor will not find any impressive remains from the classical period. But this is exactly what Thucydides predicted. In fact, Sparta was not a ‘city’ in the true sense of the word, but was made up of five unwalled separate villages, and its temples were rudimentary. Thucydides, 1.10.2:

If the city of the Spartans were to be deserted, and only the temples and the foundations of the buildings survived, I would imagine that there would be a strong disbelief after a long time had passed among the people of that time that the power of the Spartans was as great as their fame. However, they occupy two-fifths of the Peloponnese, and have leadership over all of it, as well as many allies in other places. But as Sparta is not constructed as a compact unit, and is not adorned with beautiful temples and buildings, but is inhabited in villages, according to the old Greek fashion, it would appear more inferior than it is. But if Athens were to be similarly deserted, its power would seem to be twice as great as it is, from the appearance of the city which met the eye.

Thucydides’ history is taken up with the long struggle, known now as the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), that took place between Sparta and Athens. Sparta won, and deprived Athens of her empire of island states that she had ruled since 479 BC. But Athens was not politically destroyed by its loss in the Peloponnesian War, and always remained the pre-eminent Greek state culturally and intellectually. It was always an important player in Greek affairs, and in the second half of the fourth century BC was the main opponent of the power of Macedon, first ruled by Philip II and then by his son Alexander the Great.

Another major player in Greek history was the city of Corinth, an important participant in the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC and advocate of war against Athens in 432 BC. Herodotus, Thucydides and Xenophon preserve most of what is known of Corinth’s history; it produced no major writers itself. The Isthmus of Corinth, a narrow strip of land 6 km wide, was the land gateway between southern Greece, the Peloponnese, and the rest of the mainland. Immediately beyond the Isthmus was the city of Megara, and not far beyond it Athens. The Isthmus was the invasion route for the Spartans in their expeditions against Athens in the late sixth century BC and again during the Peloponnesian War. Its importance is described by Thucydides, 1.13.5:

For the Corinthians occupied a city on the Isthmus and had always had a trading centre there, because the Greeks – both those in the Peloponnese and those outside it – in the past had dealings with each other more by land than sea, and they passed through the Isthmus. The Corinthians were powerful because of their wealth, as even the early poets illustrate, who gave it the epithet ‘wealthy’. When the Greeks took to the sea more, the Corinthians acquired ships and rooted out piracy, and provided a market for both sea and land trade, and the city became powerful from money revenues.

Corinth sent out numerous colonies in the seventh and sixth centuries BC, and none was more successful than Syracuse in Sicily, whose war-like tyrants often held sway over many of the Greek cities on the island, so much so that Pindar could describe the city as a shrine to Ares, the blood-thirsty god of war, where even the horses love to go to war! Pindar, Pythian Victory Ode, 2.1–2:

Great city of Syracuse, shrine of Ares, plunged deep in war,

divine raiser of men and horses which exult in the iron of battle.

Sicily became famous for its horses bred on its rich open plains, and one of the main pleasures of Syracuse’s tyrants was entering chariot teams in the great contests of the motherland. The poets Pindar and Bacchylides wrote victory odes in their honour. Here Bacchylides praises the tyrant Hieron for his victory in 470 BC at the games held at Delphi (the Pythian games) every four years; the Greeks believed that Delphi in central Greece was the navel of the earth. Hieron did not drive the chariot team himself, but had a trained charioteer to do this. Bacchylides, Victory Ode, 4.1–6:

Golden-haired Apollo

still loves the Syracusan city

and honours Hieron, just ruler of his city;

for the third time beside the navel of the high-cliffed land of Delphi

he is sung as a Pythian victor

through the excellence of his swift-footed horses.

Elsewhere, Bacchylides describes Hieron (Bacchylides, Victory Ode, 5.1–2): ‘General, well endowed by fortune, of the chariot-whirled Syracusans.’ Most Greeks may have thought that Delphi was the navel of the earth but for the Athenians their own city was the centre of the universe. One fifth-century comic poet summed it all up. Lysippus, Fragment 8:

If you haven’t seen Athens, you’re a blockhead;

if you’ve seen her and you’re not captivated, a donkey;

if you love it here but go away, a pack-ass.

The reader may well have gathered by now that the Greeks were not a united race. In fact in Sicily the Greeks spent as much energy fighting among themselves as attacking the natives, the Sicels, and the Carthaginians, who also laid claim to the island. The city-state was an independent unit and, as such, political fragmentation rather than unity was the reality. Although the Greeks were bound together by their common religion, customs and language, there were nevertheless local variations. There were different dialects and accents; the Athenians thought Spartan and Boeotian accents funny. In a fragmentary play of Sophocles, a character, probably Helen, notices and comments on the accent of another speaker. Sophocles, The Demand for Helen’s Return, Fragment 176:

Something in his tongue

addresses me, to detect a Spartan way of talking.

The conflict between Athens and Sparta in the fifth century BC was a case of the clash of two very different societies, with Athens open, democratic and cosmopolitan, a crucible for intellectual activity (though Socrates’ execution in 399 BC somewhat qualifies this), while Sparta was closed, conservative, ascetic, militaristic, and xenophobic (even occasionally expelling all foreigners from Sparta). Euripides in his play Andromache produced in 425 BC, six years after Sparta declared war on Athens, expressed the hatred that many Athenians must have felt for Sparta during the Peloponnesian War. Euripides, Andromache, 445–9:

Inhabitants of Sparta, most hateful of mortals

to all mankind, treacherous schemers, plotters,

masters of falsehoods, skilled contrivers of wrongs,

thinking nothing sound but every thing that is twisted,

unjust is your prosperity in Greece.

But there was much more to this civilisation than political rivalry. In this volume it is the culture of the Greeks that will be explored, examining their society, its beliefs and customs, through the words of the Greeks themselves, and observing the balance that they successfully struck between good and excess. For them, life was to be lived to the full, but there could be too much of a ‘good thing’. Pindar, Hymn, 35b:

The wise also have praised without qualification the saying,

‘Nothing in excess.’

However, the Greeks were not ‘prudes’, and life was to be enjoyed, as the same author told his listeners. Pindar, Encomion, 126:

Don’t cut back on fun in your life: it’s best

by a long shot for a man to have a happy life.

Yes, listeners. Much of Greek literature in the archaic and classical periods was not written down to be privately read but to be spoken out loud. Herodotus’ massive work of history was originally read out in sections to an audience; Pindar composed victory odes to be sung at Olympia and other athletic centres, and in the houses of the victors. Homer was sung by a skilled bard to an audience that never tired of hearing about the Trojan War, and schoolboys were set the task of memorising his epics. All the great tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides were performed before audiences, whose concerns and fears are reflected in these plays. Much of Greek literature is poetry, considered to be the gift of the nine Muses, goddesses of song and music, who dwelt on Mount Pieria, north of Mount Olympus. Bacchylides, Victory Ode, 19.1–8:

An infinite highway

of ambrosial songs there is

for whoever obtains gifts

from the Muses of Mount Pieria,

whose songs 5

the violet-eyed maidens,

the Graces bearing garlands,

dress with honour.

From this ‘infinite highway’ of poetry, as well as ordinary prose, this volume selects what is hopefully a representative collection of extracts to open up the lives of the Greeks to our scrutiny, using what they themselves wrote to arrive at an understanding of what Greek society and culture was like. It may be the case that ‘Man is only breath and shadow’ (Sophocles, Ajax the Locrian, Fragment 13) but in the case of the Greeks they were a people who have cast a long benevolent shadow over western civilisation and so the world, and whose ‘breath’ of words continues to fascinate and exert an influence. Despite the distance of time (over 2,750 years in the case of Homer) and an alien yet surprisingly familiar culture, the Greeks do speak to us – in their own words.

ONE

Gods and Mortals

One race of men, one of gods: but from a single mother, Earth,

we both take breath. But a sundering power completely separates us.

For one race is of nothing, but for the other race bronze heaven remains a safe haven forever.

Notwithstanding that, our nature is a bit like that of the immortal gods

either in greatness of mind or in our nature,

although we don’t know either by day or by night

what course Destiny has inscribed for us to run.

Pindar, Nemean Victory Ode, 6.1–7.

For the ancient Greeks there was a gulf between the race of immortal gods and that of mortals: one did not know death but the other was well acquainted with it. There was something divine about mortals, however, as the Greeks saw it, in their gifts of intellect and their emotional capacities. But in the classical period there was no possibility that mortals could aspire to divinity, and as the story of Polycrates shows, the gods guarded their prerogatives carefully. For a mortal to become like the gods was an act of hybris (‘outrage’), punished by the gods with nemesis (‘destruction’).

But the gods were not overly negative. They could be supplicated with prayer and sacrifice. The slaughter of animals in a ritual context was in fact the main way in which the Greeks worshipped the gods, who were thought of either as attending the sacrifice itself, or as enjoying the aroma of the cooking while on Mount Olympus, their home. Victims were usually led in procession to the altar, and the frieze of the Parthenon, the main temple on the acropolis of Athens, shows many animals being led to sacrifice (see illustration 1.1).

The relationship between mortals and immortals was in many ways reciprocal. The Greeks believed that the gods expected to be worshipped, but in return mortals could legitimately call upon the gods for assistance, reminding the gods of past favours mortals had done for them. This is precisely how the priest Chryses calls upon Apollo’s assistance when the Greeks will not return his daughter to him, as will be seen in the first passage below.

‘Gods’, of course, implies more than one god, and Greek religion was polytheistic in nature, with numerous deities, each of which tended to have particular areas of speciality. There were twelve main gods, the Olympians, who dwelt on Mount Olympus. Zeus was the chief god, controller of weather, generalissimo of the other gods and protector of guests and strangers (among other things). As Pindar wrote, ‘Everything is in the hands of Zeus’ (Pindar, Pythian Victory Ode, 2.49). His consort was Hera, patron of marriage. Hades and Poseidon, Zeus’ brothers, had charge of the underworld and sea respectively, though Poseidon was also the god of horses and earthquakes. Demeter, Zeus’ sister, was responsible for agriculture, and was the goddess who presided over the Eleusinian Mysteries with their promise of a better afterlife. Her daughter Persephone was abducted by Hades and became his wife and queen of the underworld. Aphrodite was the goddess of sensuality and sexuality, but also watched over the transition of girls to womanhood. She is often contrasted with Athena, the virgin goddess and protector of Athens, who had martial qualities but was also patron of weaving and crafts. However, the two are shown sitting and chatting amicably, arm in arm, on the east frieze of the Parthenon of the Athenian acropolis.

Apollo was god of prophecy, and also of plagues, and it is his arrows that spread the plague among the Greeks at Troy to punish them for their treatment of Chryses, his priest. Artemis, Apollo’s twin sister, was also skilled with arrows; she was a virgin goddess of the hunt, and also the protector of women in childbirth. Hephaestus was the god of metal work, and the Sicilians believed that volcanic Mount Etna was his furnace. Despised among even the gods was Ares, the god of war, delighting in bloodshed and gore, with no real interest in who won or lost. Hermes, with his winged sandals, was the messenger of the gods, but also a trickster and a thief. Other important gods included Dionysus, the god of wine, and Asclepius the healer, while the goddess Hecate presided over sorcery and magic.

There was a general lack of written texts; there was no Hebrew Torah or Christian Bible. Herodotus notes that Homer and Hesiod compiled the stories of the gods, but this was in no sense a theology, or a statement of principles and practices. It is sometimes said that Greek religion was not ethical in orientation; it was not pre-occupied with ideas of good or morality. In fact, some philosophers criticised the ways in which Homer and Hesiod depicted the gods as an anthropomorphic (made in human form) group of adulterous, devious egotists. But the gods were concerned with wickedness, even if their justice might be slow and take several generations to come to fruition. Zeus in particular was the god of justice, and the writings of Hesiod are especially concerned with divine interest in human wrongdoing.

For guidance in various matters, from whether or not to found a colony to how to overcome childlessness, the Greeks resorted directly to the gods. They believed that Zeus communicated his will through the god Apollo, who in turn spoke at Delphi through the medium of a woman priest, the Pythia. Delphi was the most important oracular site in Greece. Trophonius also had an oracle at nearby Lebadea, and in western Greece at Acheron the very souls of the dead themselves could be consulted.

The dead, as Odysseus sees when he consults them, have a miserable existence which only a few can escape, or at least this is the case in the Homeric epics. Death, as in all societies, was the ultimate human tragedy, but even more so when one died before one’s time, and for a parent to bury a child, particularly an adult one, was considered (as now) an especially bitter fate. A poignant scene on an Athenian vase shows a deceased boy bidding farewell to his mother and taking his go-cart with him into the afterlife, as Charon the ferryman of dead souls waits in his boat to take him to Hades (see illustration 1.2). But the Eleusinian Mysteries promised the initiated an escape from the dreariness of Hades. While some writers were pessimistic about life and growing old, the Greeks did not have a morbid fascination with death, nor did they engage in any form of fatalism (or nihilism). They enjoyed feasts and games for the gods, and lived their private lives to the full. The gods loved feasting and entertainment and what their lives had to offer, and in this way the gods reflected their human worshippers.

PRAYER AND DIVINE VENGEANCE

The Greeks have been at the walls of Troy for nine years, unsuccessful in their attempts to take the city. The Iliad opens in the tenth year with a plague sent by the god Apollo to punish the Greeks (the Achaeans) for the way in which his priest Chryses has been treated. His daughter had been captured by the Greeks in a raid, and was part of Agamemnon’s booty. He is the leader of the Greeks, and like Menelaus is the son of Atreus, and hates Calchas the seer for the advice that he gives below. Agamemnon demands that if he gives up the priest’s daughter he must have another woman as his prize, and insists that Achilles, the great hero, give up his prize (the woman Brisis) to him. So begins a fearful argument, and Achilles refuses to fight in battle anymore. Homer, Iliad, 1.8–32:

Which of the gods brought these two into contention?

It was the son of Leto and Zeus, Apollo, for angry against king Agamemnon

he aroused the foul pestilence throughout the army, and the people were perishing, 10

for the son of Atreus had dishonoured Chryses, Apollo’s priest:

for Chryses came to the swift ships of the Achaeans

bearing a ransom beyond reckoning to free his daughter,

carrying in his hands the ribbons of far-shooting Apollo

on a golden staff, and entreated all the Achaeans, 15

but especially the two sons of Atreus, the marshals of the army:

‘Sons of Atreus and you other well-greaved Achaeans,

to you may the gods who have their homes on Olympus grant

that you sack Priam’s city, and have a fine return home:

but give back to me my beloved daughter, and take the ransom, 20

honouring Apollo the far-shooting son of Zeus.’

Then all the rest of the Achaeans cried out in agreement,

to honour the priest and to accept the splendid ransom:

but this pleased not the heart of Agamemnon, son of Atreus,

but he sent Chryses harshly away, laying a forceful command upon him: 25

‘Do not let me, old man, find you by the hollow ships

neither dallying now nor later on coming again,

in case your staff and the ribbons of the god not protect you.

I will not set her free: before that happens old age will befall her

in my house in Argos, far from her father-land 30

plying the loom and sharing my bed.

But leave, do not anger me, so that you may go safer.’

Agamemnon’s refusal was to have dire consequences for the Greeks. Chryses prays to Apollo, who hears his priest. This is the earliest recorded Greek prayer, and several features of it are important. Chryses addressed Apollo by his cult epithets (such as Smintheus in line 39), and this was normal in Greek prayers. The person praying addressed the god, sending the prayer in the right direction: there were many gods, and the prayer must go to the right one. More importantly, Chryses reminds the god of past services; the old priest now, so to speak, calls in his debts. A bronze statue shows a young man lifting his hands in prayer to the gods (illustration 1.4). Greek men would not kneel before the gods: that was a position of worship adopted only by women. The god acknowledges Chryses’ piety, with dreadful consequences for the Greek army. Homer, Iliad, 1.33–129:

So Agamemnon spoke, and the old man was gripped with fear and obeyed his word;

he went silently along the shore of the loud-roaring sea:

and fervently the old man as he went along alone prayed to 35

Lord Apollo, whom lovely-haired Leto bore:

‘Hear me, you of the silver bow, who bestrides Chryse

and sacred Cilla, and rule Tenedos in might,

Smintheus, if ever it pleased you that I built your temple,

or if ever I burned to you fat thigh pieces 40

of bulls and of goats, accomplish for me this desire:

let the Danaans repay my tears by your arrows.’

So he spoke praying, and Phoebus Apollo heard him,

and he came down from the peaks of Olympus, angry of heart,

bearing on his shoulders the bow and covered quiver. 45

The arrows rattled on the shoulders of the striding,

wrathful god, and he came like the night.

Then he sat down away from the ships, and loosed an arrow:

a terrible twang resounded from the silver bow.

First he attacked the mules and the swift-footed dogs, 50

and then loosening the piercing arrow against the men themselves

he struck: and the crowded pyres of the corpses burned densely.

Nine days throughout the army the god’s arrows flew,

but on the tenth Achilles summoned the people to assembly,

for the white-armed goddess Hera put it into his mind to do so: 55

for she pitied the Danaans, seeing them dying.

And when they were collected together and assembled,

Achilles fleet of foot stood up among them and spoke:

‘Son of Atreus, now I think we, driven back,

will return home, if we can escape death, 60

if indeed war and plague alike are to slaughter the Achaeans.

But, come, let us consult a soothsayer or priest,

or even a dream-interpreter, for even a dream comes from Zeus,

who can explain why Phoebus Apollo is so wrathful,

whether he blames us because of an unfulfilled vow or sacrifice, 65

and if perhaps by the aroma of lambs and unblemished goats

he is willing to ward off from us this destruction.’

When he’d finished speaking he sat down at once: and from among them

Calchas son of Thestor stood up, the best of the diviners,

who had knowledge of what was, what was to be, and what had been, 70

who had guided the Achaean ships into Ilion

through the prophetic arts given to him by Phoebus Apollo.

With good intentions he addressed them, advising so:

‘Achilles, loved by Zeus, you ask me to explain

the anger of lord Apollo, who strikes from far away. 75

So I will speak: but take heed and swear to me

that you will willingly defend me with words and hands.

For I think that I will make angry a man who rules

mightily over all the Argives and whom the Achaeans obey.

For a king is too strong when he is angry with a lesser man, 80

and even if on the day itself he swallows down his anger

afterwards he holds a grudge until it finds fulfilment in his heart.

So tell me if you will keep me safe.’

Fleet of foot Achilles said in answer to him:

‘Have courage, and speak, whatever prophecy you know. 85

For by Apollo, loved by Zeus, to whom you pray Calchas,

revealing the oracles to the Danaans,

no one while I live and have sight on the earth

will lay heavy hands on you beside the hollow ships,

out of all the Danaans, not even if it is Agamemnon you speak of, 90

who now claims to be by far the best of the Achaeans.’

And then the faultless seer took courage and said:

‘It is not because of either a vow or a sacrifice that Apollo blames us,

but because of the priest whom Agamemnon dishonoured,

not giving back his daughter and not accepting the ransom: 95

because of this the far-shooter gives grief and will go on doing so

nor will he drive away the dreadful plague from the Danaans

until we give to the dear father the quick-glancing maiden

without a price-tag, without a ransom, and also lead a sacred sacrifice

to Chryse: then we might appease and persuade him.’ 100

When he had spoken so he sat down again, and among them stood up

heroic, wide-ruling Agamemnon, son of Atreus,

angered: great rage his black soul completely

filled, and his eyes were like blazing fires.

He spoke to Calchas first, his visage baneful: 105

‘Seer of evil, not once have you prophesied a good thing to me:

always your heart delights in evil prophecy,

not ever yet have you spoken a propitious word or brought such to pass.

And now in the assembly of the Danaans you prophesy that

it is on account of this that the far-shooter afflicts them: 110

because I would not accept the splendid ransom

for the girl Chrysis, since I greatly desire to have her

in my house. For I prefer her over Clytemnestra

my wedded wife, since she is not inferior to her,

neither in build nor in stature, nor in intellect or handiwork. 115

But even so I am willing to give her back, if this is the better course:

for I want my people to be preserved and not perish.

However, get ready for me at once a prize so that not I alone

of the Argives am without one; that would not be fitting:

for all of you are witnesses that my prize goes elsewhere.’ 120

Then swift-footed god-like Achilles answered him:

‘Most glorious son of Atreus, most acquisitive of men,

how will the great-hearted Achaeans give you a prize?

For we don’t know of any common treasure hoard lying around,

but what we captured from the cities is distributed, 125

and it isn’t right to take this back from the people.

But now give the girl back to the god Apollo, and the Achaeans

shall repay you three or four times, if ever Zeus

will give us the well-walled city of Troy to sack.’

PRAYER AND SACRIFICE

Achilles has to give up his prize, Brisis, to Agamemnon, and so withdraws from the fighting in a fit of temper. The Greeks experience several disasters in battle, and Agamemnon attempts to win him over. The Greek hero Phoenix attempts to persuade Achilles to accept Agamemnon’s gifts and return to the battle outside Troy. Homer, Iliad, 9.499–514:

And mortals with incenses and pious offerings

and with libation and the aroma of the sacrifice 500

supplicating the gods turn their anger aside when anyone might transgress and sin.

For Prayers are the daughters of great Zeus,

they are lame, shrivelled, and cast their eyes sideways,

and are mindful to go after Ate, goddess of ruin and sin,

Ate, both mighty and swift of feet, who so greatly 505

outdistances the Prayers, arriving first in every land

harming men: and the Prayers come after as healers.

He who shall revere these daughters of Zeus as they approach near,

him they will greatly advantage, and they hear his prayers:

but if someone denies and stubbornly refuses them, 510

departing, they pray to Zeus son of Cronus

that Ate will at once follow him, so that being hurt he might pay the penalty.

So, Achilles, grant you also that the daughters of Zeus receive

honour, such as bends the mind of other good men.

Telemachus has come to ‘sandy Pylus’ to find out any information he can about his father Odysseus and his return from Troy. There he finds Nestor on the beach sacrificing black bulls to Poseidon. Nestor entertains him; the next day at dawn another sacrifice, this time to Athena, is held before Telemachus sets out for Sparta to visit Menelaus and see if he also has any news of Odysseus. The lustral water was used to wash the hands of the main presider over the sacrifice (line 440); here the barley in the basket was tossed on the victim’s head to make it nod, so assenting to its own destruction: the gods were not pleased with unwilling victims. These details of sacrifices are shown on numerous Greek vases (see illustration 1.3). It was often the duty of young girls to carry this basket. The horns of the victim could be covered in gold foil so that the beast had a more pleasing appearance. In the museum at Delphi, the remains of gold foil that covered an entire beast can be seen: a magnificent offering to the god there, Apollo. Homer, Odyssey, 3.430–63, 470–2:

So Nestor commanded, and they all scampered to their tasks. The cow was brought 430

from the plain, and from the even-keeled, swift ship

came the companions of great-hearted Telemachus; the smith arrived

carrying in his arms his bronze tools, the gear of his trade,

anvil and hammer and the well-made tongs

with which he worked the gold. And Athena came 435

to receive the sacrifice. And the old charioteer Nestor dished out

the gold. The smith prepared and fashioned it over the horns of the cow

so that the goddess would delight when she saw the offering.

And Stratius and god-like Echephron led the cow by its horns.

And Aretus came from the storeroom carrying the lustral water for them 440

in a bowl decorated with flowers, and in his other hand barley grain

in a basket. Thrasymedes, staunch in battle, stood ready

with the sharp axe in his hands to cut down the cow.

And Perseus held the bowl to catch the blood. The old charioteer Nestor

commenced the sacrifice, washing his hands and sprinkling the barley. 445

Praying earnestly to Athena he made a first offering of hairs from the cow’s head, throwing them into the fire.

Now when they had prayed and strewn the barley grain over the beast,

immediately Thrasymedes, the high-hearted son of Nestor, standing near

struck the blow: the axe severed the tendons of the neck, and loosed

the strength of the cow. The women screamed the sacrificial ululation, 450

both the daughters and daughters-in-law and the venerable wife of Nestor,

Eurydice, the oldest of the daughters of Clymenus.

And then the men lifted the cow from the broad-wayed earth and held it

as Peisistratus, leader of men, cut its throat. And when

the black blood had flowed from her, and the life fled the bones, 455

they quickly butchered the carcass, and immediately sliced out the thighs,

doing everything in proper order, and covered them,

making a double layer of fat, and arranged raw flesh on them.

Then the old man burned this on shavings of wood and poured sparkling wine

over them: the young men beside him held five-pronged forks in their hands. 460

But when the thighs were completely consumed in the flames and they had tasted the entrails,

they carved the rest up into pieces and placed it on spits,

roasting it, holding the pointed spits in their hands. 463

Now when they had roasted the outer flesh and drawn it off the spits, 470

they sat down and fell to the feast: and high-hearted men waited

on them, pouring wine into golden goblets.

Hesiod gives advice on the importance of approaching the gods in

prayer with clean hands:

Hesiod, Works and Days, 724–6:

Don’t ever pour a libation of sparkling wine after dawn with unwashed hands

to Zeus nor to any other of the immortal gods: 725

for they will not give ear to you, but will spit your prayers back at you.

Sacrifices established a relationship between the worshippers and the gods. Some argued that they could do much more, but Plato is critical of practices that claim a greater efficacy for sacrifices. Plato, Republic, 364b–5a:

(364b) But the most amazing of all these stories concern the gods and virtue, and how it is the gods who consign misfortunes and a wretched life to many good men, and the opposite fate to wicked men. Begging priests and soothsayers knock on the doors of the wealthy, persuading them that sacrifices and incantations have furnished them with power from the gods, so that any wrong which he himself has committed, or his ancestors, (364c) can be atoned for through pleasant festivals, and also if he wishes to harm an enemy for a small price he will be able to harm both just and unjust alike, with magic lore and binding spells, with which they claim they can persuade the gods to serve them. And for all these claims they quote evidence from the poets, and about the easiness of doing wrong they cite Hesiod:

Wrong can be chosen easily and in plenty

(364d) the road to her is smooth, and she lives nearby:

but the gods have placed sweat on the road of virtue,

and a certain long, steep road. Others quote Homer as a witness to the misleading of gods by men, since he also wrote:

The gods themselves are moved by prayers

and men entreating with sacrifices and appeasing vows

(364e) and libations and the aroma of burnt sacrifices turn aside the wrath

of the gods whenever anyone has transgressed and sinned.

And they pull out a host of books by Orpheus and Musaeus, descendants as they claim of the Moon and the Muses, which they employ in their rituals, persuading not just individuals but also cities that there are both remissions and purifications from wrong-doings through sacrifices and pleasant enjoyments for those still living, (365a) and also for the dead, which they call initiations, which deliver us from evil in the hereafter, but that a terrible fate is in store for those who haven’t sacrificed.

Greek religion was based on the assumption that the gods did have an individual relationship with those who honoured them, and did come to their worshippers’ assistance in return for prayer, sacrifice and reverence. Menander here places in the mouth of a character a deliberate satire on philosophic ideas about the gods. Menander, The Arbitrators, 1084–99:

Onesimus: Do you think that the gods lead such a leisured existence

as to apportion bad and good daily 1085

to each person, Smicrines?

Smicrines: What are you saying?

Onesimus: I’ll show you clearly. There are, to speak in rough figures,

all up one thousand cities. In each of these

there lives thirty thousand men. Can the gods

punish or preserve each one of them? How? 1090

That would make the life of the gods hard work.

You’ll ask: ‘Don’t the gods spare us a thought?’

They’ve given to abide with each man a guardian:

his character. This is on duty inside us,

punishing those who treat it badly 1095

and guarding those who treat it well. This is our god,

the one responsible for each man’s doing

good or bad. In order to prosper,

please it by doing nothing harmful or stupid.

THE SOULS OF THE DEAD AND THE UNDERWORLD

The suitors for Penelope’s hand, who had wooed her in Odysseus’ absence, have been slain by him on his return to his home. The psyche (the soul or spirit) of each is now guided by Hermes to Hades. Elsewhere (but not in this passage) he is called Hermes Psychopompus, the ‘soul leader’. Homer, Odyssey, 24.1–18:

Hermes summoned the souls of the suitors.

He held in his hands his beautiful golden wand

with which he enchants the eyes of those he wishes,

while others he awakens from their sleep.

Rousing the souls with this he led them, and they followed with shrill cries. 5

As when bats in the depths of a wondrous cave

fly about crying shrilly, when one of them has fallen from the

chain of bats on the rock, with which they cling to each other,

so the souls went with him crying shrilly: and Hermes the Healer

led them down through the dank pathways. 10

They journeyed past the streams of Ocean, and the White Rock,

and went by the gates of the Sun and the land of dreams,

and quickly arrived at the field of asphodel

where dwell the souls, phantoms of men whose toil has ended.

Here they came upon the soul of Achilles, son of Peleus 15

and Patroclus and Antilochus without rival

and of Ajax, who best was in appearance and build

out of all the Greeks, next after the peerless son of Peleus.

Zeus made a race of heroes, who fought at Troy: some went down to Hades, but others had a happier afterlife, and were physically assumed (‘translated’) to a better place, the Isles of the Blessed, where they enjoyed a utopian immortality. Hesiod, Works and Days, 168–73:

To others father Zeus, son of Cronus, settled at the ends of the earth

and gave life and habitation unlike that of men,

and there they live with untroubled heart 170

in the Isles of the Blessed along the shore of deep-eddying Ocean,

contented heroes, for whom honey-sweet fruit

the grain-yielding fields bear copiously thrice a year.

The sorceress Circe advises Odysseus that before proceeding on his homeward journey he must consult the spirits of the dead at Acheron, in order to speak to Teiresias the seer. Although the actual ritual here described by Homer does not appear to have been practised by the Greeks of classical times, there was an oracle of the dead at Acheron (in southern Epirus on the west coast of northern Greece), where consultants called up the dead and received advice. The ruins of the nekyomanteion, oracle of the dead, can still be seen there. The remains of metal machinery there were once thought to have been part of an elaborate contrivance used by the priests to fake the appearances of ghosts, but the metal pieces have now been identified as catapult parts. The Greeks did not need to fabricate their religion in any way. The black ram is typical of the black-animal offerings often made to the deities of the underworld (line 33). Erebus is the place of the dead (line 37); Aeaea was the island of Circe (line 70). Here Odysseus describes his consultation. Homer, Odyssey, 11.23–80:

Here Perimedes and Eurylochus held the victims,

and I, drawing the sharp sword from beside my thigh,

dug a pit, a cubit in length in both directions, 25

and poured around it a libation to all the dead,

first one of honey mixed in milk, and after that one of sweet wine,

and the third of water. And over it I sprinkled white barley.

Fervently I implored the feeble heads of the dead,

that returning to Ithaca I would sacrifice in my palace a cow 30

that had not calved, the best I had, and pile up the altar with fine gifts,

and that separately to Teiresias alone I would sacrifice a ram,

completely black, the prize ram of my flocks.

And when with both vows and prayers I had supplicated

the tribes of the dead, taking the sheep I slit their throats 35

over the pit, and their dark-coloured blood flowed. The souls

of the dead who have gone below gathered from out of Erebus:

brides and young unmarried men and old men worn out with toil,

and tender virgins with hearts bearing fresh sorrow,

and many wounded with bronze spears, men slain in war 40

wearing their battle-gear stained with gore.

These crowded around the pit on all sides

with unspeakable shrieking: and pale terror gripped me.

Then I urged on and ordered my companions

to skin the sheep, those that lay there slaughtered 45

with the pitiless bronze, and to burn them, and to pray to the gods,

to mighty Hades and his consort dread Persephone.

Myself, drawing the sharp sword from beside my thigh, I

squatted there, not allowing the feeble heads of the dead

to come nearer the blood, until I had questioned Teiresias. 50

The first to come was the soul of my companion Elpenor:

for not yet had he been buried beneath the broad earth

for we had left his corpse behind in Circe’s palace,

and he was unmourned and unburied, since another task urged us on.

When I saw him I burst into tears, and my heart pitied him, 55

and I spoke out loud to him, addressing him with winged words:

‘Elpenor, how did you come under the murky gloom?

You’ve come quicker on foot than I in my black ship.’

I said this, and groaning he answered me with a word: ‘Son of Laertes,

Odysseus of the many ruses, sprung from the race of Zeus, 60

an evil destiny of a god undid me, and immeasurable wine.

When I had laid down on Circe’s palace roof to sleep, I didn’t think

when I went to descend back down the long ladder,

but fell straight off the roof: and my neck

was broken off the spine, and my soul fled down to Hades. 65

Now I beg you, by those we left behind, who are not present,

by your wife and father, who reared you as a baby,

and Telemachus, your son, whom you left an only child in your palace:

for I know that going from here, out of the house of Hades,

you will put in again at Circe’s island of Aeaea in your well-built ship: 70

there, then, I call upon you lord not to forget me.

Don’t abandon me unmourned and unwept, going and departing

from there, in case I become a cause of wrath to you from the gods,

but burn me in my armour, whatever is mine,

and pile up a memorial for me, by the shore of the olive-grey sea, 75

and for those that will come after, to learn of me, a wretched man.

Complete these things for me, and plant my oar on the mound,

with which I rowed when I was alive among my companions.’

He said this, and I replying said to him,

‘Wretched man, I’ll complete and do all these things.’ 80

Odysseus’ mother comes up, but she cannot recognise her son; he cries and is full of pity for her: she was alive when he left for Troy but died during his travels. Nevertheless he will not let her taste the blood until he speaks to Teiresias. The seer makes many predictions, and then Odysseus asks how he might speak to his mother; she refers to the practice of cremation (line 220). Homer, Odyssey, 11.140–53:

But come, tell me this Teiresias, and answer truthfully: 140

I see the soul of my departed mother:

she is sitting quietly near the blood, and doesn’t

deign to see or talk to her own son.

Tell me, lord, how can she recognise that it is me?’

So I spoke, and he answered me in reply: 145

‘Easy is the word that I will say, and will place in your mind.

Whomever of the dead who have gone below you’ll allow

to draw near the blood, that one will speak to you truthfully,

and to whom you begrudge this, he will then go back again.’

Having said this the soul of lord Teiresias went within 150

the house of Hades, when he had spoken his prophecies:

then I waited there, steadfast, until my mother came

to drink the dark-coloured blood. At once she recognised me.

Odysseus and his mother exchange news, and she reassures him of his wife’s faithfulness. He tries three times to embrace his mother, and fails; in his distress he asks her why this is so. Homer, Odyssey, 11.204–22:

But I was troubled in my mind and wished

to embrace the soul of my departed mother. 205

Three times I lunged towards her, my heart desiring to grasp her,

three times out of my hands like a shadow or a dream

she flew. And the pain grew sharper within my heart,

and I spoke to her, addressing her with winged words:

‘My mother, why don’t you now remain still for me, desiring to embrace you, 210

so that even in the house of Hades we might throw our loving arms

around each other and have our fill of chill lamenting?

Or is this just a phantom which dread Persephone conjures up for me

so that I might mourn and groan still more?’

I said this, and immediately my stately mother replied: 215

‘Ah me, my child, ill-fated above all other men,

Persephone the daughter of Zeus doesn’t cheat you in any way,

but this is the natural way for mortals, when one dies.

For no longer do the sinews keep the flesh and bones together,

but the mighty prowess of the blazing fire conquers 220

as soon as the spirit leaves the white bones,

and the spirit like a dream flits about and flies away.

Odysseus goes on to speak to other souls of the dead. After this, he sees the torture chambers of hell. In mainstream Greek religion, the dead were not punished for the sins of this life. For all alike, except for particular heroes, a dreary existence in the afterlife was their lot. The main exception were the initiates in the Eleusinian Mysteries, who were thought to have a happy existence after death. But there were several mythical figures punished in Hades. In the Odyssey, Tityus, Tantalus and Sisyphus are all subjected to various tortures of a refined kind. All had violated Zeus’ laws and these figures and their punishments were meant as a warning to others. Tantalus is ‘tantalised’ for eternity. Homer, Odyssey, 11.576–600:

I saw Tityus, son of glorious Earth,

lying on the ground, stretched over nine acres,

and two vultures sat on either side tearing at his liver, plunging inside

his bowels, and he could not beat them away with his hands.

For he had accosted Leto, the glorious consort of Zeus, as she 580

journeyed through Panopeus of the beautiful countryside, toward Pytho.

And I saw Tantalus enduring strong torments,

standing in a pool with the water nearly up to his chin.

Parched, he would make as if to drink, but he could not take and drink any:

for as often as the old man stooped desiring to drink, 585

as often would the water disappear, sucked away, and at his feet

the black earth would appear, dried up by some divine power.

And trees, their foliage high up, produced abundant fruit above his head,

pear, pomegranate and apple trees with their shiny fruit,

and sweet fig and flourishing olive trees: 590

but as often as the old man stretched out with his hands to grasp them

the wind tossed them to the shadowy clouds.

And I also saw Sisyphus enduring strong torments,

lifting up a gigantic boulder with both hands.

Truly, with both hands and feet braced against 595

the boulder he would push it up to the crest of a hill, but then whenever

it was about to roll over the top, then its mighty weight turned it back again:

then again to the level ground the ruthless stone rolled.

But he would again strain, pushing it up, and the sweat

rolled down his limbs, and a cloud of dust rose over his head. 600

The tyrant Periander of Corinth also consulted the oracle of the dead at Acheron (as had Odysseus), and the spirit of his dead wife gave him information about some money that he had buried but the location of which he had forgotten. He had killed his wife, then slept with her. Herodotus, 5.92η1–4: