Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Patrick Wright's memoir opens on a diplomatic crisis. A growing number of countries are threatening to boycott the Commonwealth Games in protest of the British government's handling of South African apartheid. And the problems only get worse. Patrick Wright was one of the pre-eminent diplomats of his day, putting him at the forefront of some of the late twentieth century's most important global events. His six years at the FCO found him dealing with the backlash from the Falklands War, the collapse of the Soviet Union, strained relations with the EU, the First Gulf War and, perhaps most challenging of all, the 'fire and glares' of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Lord Wright's account is not only an essential documentation of a significant historical period, but witty and entertaining throughout. He revels in gossip, despairs at the mischievous press 'painting lurid pictures of Britain versus the Rest', recalls numerous amusing scenarios and is rather brutal in his assessment of various high-profile political figures.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 508

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

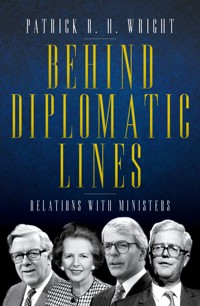

BEHIND DIPLOMATIC LINES

RELATIONS WITH MINISTERS

An edited version of diaries recording the life of a Foreign Office Permanent Under-Secretary from 1986 to 1991.

PATRICK R. H. WRIGHT

CONTENTS

1986

20 JUNE 1986

One week before taking over as Permanent Under-Secretary (PUS) from Sir Antony Acland, we were both invited to lunch with Mrs Thatcher. She opened the conversation by thrusting a newspaper cutting about Oliver Tambo in front of us, saying that it proved that we should not be talking to him (having agreed that morning that Lynda Chalker, a Minister of State in the Foreign Office, could meet him). She continued, both before and at lunch, to express her views about a return to pre-1910 South Africa, with a white mini-state partitioned from their neighbouring black states. When I argued that this would be seen as an extension of apartheid and homelands policy, she barked: ‘Do you have no concern for our strategic interests?’ I replied: ‘Of course, Prime Minister; but I don’t think this is the way to protect them.’

Otherwise, this was a very agreeable occasion, with the Prime Minister occasionally reverting to the topic of South Africa. She paid very warm tributes to Antony Acland, with the snide comment that his imagination and initiative were constantly being eroded by the unimaginative approach of the Foreign Office. She was also very complimentary about Charles Powell [now Lord Powell of Bayswater], whom she described as the best private secretary she had ever had (a compliment I had personally heard her pay to his two predecessors). One of them, Sir John Coles, later told me that, at his farewell dinner at No. 10, Margaret Thatcher had gone over the top in her compliments, glaring at his successor and saying: ‘Mr Powell is going to have an extremely difficult job succeeding you.’ Her devotion to her private secretaries was to cause me endless problems during the next five years, not unlike the problems that my predecessors had encountered during Sir Philip de Zulueta’s time as private secretary to Harold Macmillan. This prime ministerial reliance on their private secretaries ultimately made it impossible for de Zulueta, as it did for Charles Powell, to return to the diplomatic service.

On leaving No. 10, Antony and I bumped into the Foreign Secretary, Geoffrey Howe, who looked slightly put out that I had lunched with the Prime Minister before my first formal call on him. I therefore arranged to bring forward my call, the office having deliberately delayed it until I took over on 30 June.

24 JUNE 1986

I paid my first call on Geoffrey Howe, with only Tony Galsworthy (his private secretary) present. I talked about my impressions of the service, after an extensive tour of posts in Africa and the Far East, pointing out the financial strains on members of the service, particularly those abroad who, unlike their home civil service married colleagues, were unable, in those days, to benefit from double salaries. Geoffrey talked about his own impressions of the office, and his worries about staffing on Falkland Islands and other dependent territories questions. He also worried about one of his junior ministers, who he thought was much too ready to accept official advice without questioning it. No talk about the Prime Minister, though he was already having a very difficult time with her, particularly on South Africa, where their views were poles apart.

25 JUNE 1986

At a lunch with Robert Armstrong and Tom Brimelow (reminiscent of a lunch twelve years earlier, at which they had ‘vetted’ me for my job as Harold Wilson’s private secretary), Robert Armstrong described relations between the Prime Minister and the Foreign Office as worse than he could ever remember with any Prime Minister. When discussing her views about another Foreign Office official [whom Antony thought – as it turned out, wrongly – was a likely successor to myself], Robert replied: ‘All right, until 11 a.m.,’ explaining that the Prime Minister had emerged from Cabinet to see this official talking to the Foreign Secretary. In present circumstances, this was apparently enough to damn anyone.

Margaret Thatcher’s contemptuous opinions of the diplomatic service contrasted strongly with her complimentary views on almost every individual diplomat she met [sadly, not many, in view of the way in which the doors of No. 10 were fiercely guarded by her private secretary]. After almost every foreign trip she made, she appeared to be impressed by the head of mission (particularly if he was tall and good-looking), often complaining to me that so-and-so was ‘far too good for X; why is he not in Paris or Washington?’

Curiously, one of her reservations was beards. When a bearded colleague of mine started a Foreign Office job which was likely to involve close contact with No. 10, I warned him [would this be acceptable nowadays?] that it might be better, given Mrs Thatcher’s known prejudices, if he shaved it off. He replied that this put him in a dilemma between a Prime Minister who disliked beards, and a wife that liked them. But he shaved it off! Moustaches were also a problem. Of one moustached colleague, Margaret Thatcher is reported to have claimed: ‘The trouble is, he looks like a hairdresser.’

Sherard Cowper-Coles, the private secretary I was to inherit from Antony Acland, told me that he had heard from Tony Galsworthy that my initial talk with Geoffrey Howe had gone very well. [I did not record, at the time, an earlier talk I’d had with Geoffrey Howe soon after my return from Saudi Arabia.] Geoffrey said that there would, of course, be many things we would need to discuss, but he had one request to make. ‘We must’, he said, ‘try to slow the merry-go-round, and leave heads of mission longer in post.’ I replied that this was music to my ears. But I reminded him of two things: first, that he had pulled me out of Saudi Arabia after eighteen months to become his PUS; and second, that his request was pretty ripe, coming as it did from a member of a Cabinet that had had twelve secretaries of state for Trade and Industry in thirteen years.

27 JUNE 1986

Today I went through the Green Safe, skimming the files, including several dating back to my days as private secretary to Sir Paul Gore-Booth in the mid-1960s. One of these concerned an Iraqi Prince, Prince Sami, who claimed a payment from the secret fund, on the grounds that he had been deprived of his inheritance by the Iraq Petroleum Company. He had once turned up at the Foreign Office with his entire family and threatened my predecessor, Nicholas Gordon Lennox, that he would camp on the premises until he was paid. My own earlier contact with Prince Sami had been in Washington where, as private secretary to the ambassador, I was instructed by Douglas Hurd [then private secretary to the PUS] to deliver a message to Prince Sami in a particularly expensive Washington hotel, telling him that he would receive no more payments.

The lead story in the Evening Standard today was of a serious split between Geoffrey Howe and Margaret Thatcher, including an alleged (and accurate) quote of her saying in Cabinet, on the topic of his mission to Africa: ‘If you feel like that, perhaps you had better stay at home.’ I was told last night that Geoffrey, in fact, minds these attacks much more than he shows. I discussed with Antony and Sherard last night whether, like Antony, I was going to be faced with a Foreign Secretary resigning in my first week as PUS (Lord Carrington having resigned over the Falklands on Michael Palliser’s last day before Antony succeeded him as PUS). Sherard thought that Geoffrey loved the job (and Chevening) much too much. Antony commented that you wouldn’t know it, and he thought that the office would be astonished to be told it.

I called on Janet Young, the FCO minister in the House of Lords, who became a good friend, but who sadly did not enjoy Geoffrey’s confidence (as he made abundantly clear during a large office meeting on the Turks and Caicos Islands). The trouble is that Geoffrey tends to reflect his own uncertainty over taking decisions by looking for faults in others.

2 JULY 1986

I called on Lynda Chalker, who confessed to having had a crisis of confidence. She obviously regards herself as a non-intellectual, surrounded by brilliant officials who all quote Latin at her. I reminded her that by far the most popular and most successful Foreign Secretary since the war had been Ernie Bevin, who had commented on a marginal reference to the phrase ‘mutatis mutandis’: ‘Please do not write in Greek; I have never learned it.’

3 JULY 1986

This morning was the first of many presentations of credentials, for which I wore full diplomatic uniform. [There is a picture of me, accompanying the credentials ceremony for the United States ambassador, Ray Seitz, in 1991 on the back of his book Over Here, with the comment, in the text itself, that I was ‘immaculate in [my] dark-blue diplomatic uniform and cradling a great plumed hat across [my] front like a pet ostrich’. Simon McDonald later sent me a Christmas card showing himself in diplomatic uniform, with a picture on the back of me in an identical pose.]

On this occasion, the talk with the Queen was mainly about whether the German von Weizsäcker had used the English words ‘common sense’ in his speech at the German state banquet on the previous evening out of politeness, or because there was no German word for it. Von Weizsäcker’s speech-writer had told me that the Germans normally used the English words, and he did not think there was a German equivalent. This recalls Harold Nicolson’s claim, which I was frequently to quote in my talks on diplomacy, that common sense was perhaps the most important qualification for a diplomat.

At the later banquet, [my wife] Virginia and I talked to Lord Hailsham, who denied that he kept a diary. He claimed that Barbara Castle had dictated her diaries immediately after the event, with subsequent re-editing two weeks later. Tony Benn’s fairly blatant keeping of diaries during Cabinet meetings once provoked Denis Healey into cutting short a presentation to Cabinet with the words: ‘Tony, am I speaking too fast for you?’

I attended a meeting with Geoffrey Howe this afternoon on South Africa, in the face of indications that P. W. Botha may not see him on his first visit, which would look very bad. Geoffrey realises what a viper’s nest he is walking into.

5 & 6 JULY 1986

Virginia and I were invited to spend the weekend with the Howes at Chevening [which they adored, and which caused them more regrets than almost anything else when Geoffrey was kicked upstairs to be Deputy Prime Minister]. Other guests included the opera singer Geraint Evans and his wife Brenda. After dinner on the Saturday evening, there was a sing-song, for which I was invited to play the piano. Geraint, who had apparently sworn that, in retirement, he would never sing again, retreated to the window looking out over the garden. But the sound of a succession of songs from The Scout’s Song Book through to Irish Ballads and The Messiah was too much for him. [Happily, I still have a photograph of me accompanying Geraint, with Geoffrey Howe almost sitting on my lap, and with everyone else ranged around the piano.]

Next morning, Geoffrey and I retired to work on his box. The omens for his South African visit were not looking good, and he was coming to the conclusion that we might have to change our policy on sanctions. The Prime Minister would be very difficult indeed, and he was facing his next bilateral with her tomorrow.

The Sunday Telegraph carried headline stories today – so far as I could see, without any justification – that Geoffrey might be considering resignation. He discussed with me the idea of holding a meeting this evening, but decided against it. The trouble is that, for domestic political reasons, the government has felt bound to present a more optimistic picture of the prospects of moving P. W. Botha than is remotely justified.

8 JULY 1986

An early start today, with an 8 a.m. meeting on Southern Africa. Geoffrey Howe decided that he should go ahead with his planned visits to Zambia and Zimbabwe, in the face of P. W. Botha’s refusal to see him until later in the month. I wrote him a personal letter to thank him for the Chevening weekend, and expressing the hope and confidence that the story in the Sunday Telegraph about his resignation was completely unfounded.

At 11 a.m., I attended a meeting in Lady Young’s office to discuss her parliamentary questions in the Lords, with all parliamentary private secretaries (PPSs) present. It is quite a challenge for Lords ministers to face a wide variety of questions, and I once heard a former Secretary of State claim that he found questions in the Lords much more demanding than those he had faced in the Commons, because questions in the Lords usually came from peers who had deep knowledge and experience of the subject.

On the other hand, there is the probably apocryphal story that Lord Goronwy-Roberts, when the Lords minister, received a brief which ended with the words: ‘This is not a very good reply, but it should do for the House of Lords’ – and he read it out.

8 JULY 1986

I called this morning on Tim Eggar, the parliamentary under-secretary described in the parliamentary guide as ‘very right wing, and a Labour basher’ – a rather macho character, who obviously feels, like most junior ministers, excluded from decision-making. [He later developed a strong interest in diplomatic car parking and non-payment of parking fines, adopting it as almost a personal crusade.]

At dinner this evening, Lord Chalfont was quoted as comparing the Foreign & Commonwealth Office’s (FCO) relationship with its junior ministers to that of an oyster and a piece of sand: a source of constant irritation, and only likely in the rarest instances to produce a pearl.

[My memory of leak procedures during my time as deputy under-secretary (DUS), when Lord Chalfont was a Foreign Office minister, having previously been the defence correspondent on The Times, was that the inquiry nearly always ended with the conclusion that Chalfont himself was almost certainly the source, but never proceeded with. I once told him this many years later, when we were colleagues on the cross benches of the House of Lords.]

9 JULY 1986

Ghana today pulled out of the Commonwealth Games, with an offensive démarche in Accra, followed by Nigeria. I spoke to Sonny Ramphal, and asked him to do what he could to stop the rot. I attended a large office meeting with Lynda Chalker to agree instructions to Commonwealth posts.

I had a meeting with Robert Armstrong to discuss office buildings. The Prime Minister has revealed a clear, and predictable, prejudice against the FCO and Overseas Development Administration (ODA), and is trying to block the ODA’s agreed move to Richmond Yard, to which everyone thought she had agreed a long time ago, but which she now denies. Her prejudice against the FCO building in Downing Street is alleged once to have provoked her complaint that the FCO blocked all the sunshine from No. 10.

I dined at the American embassy to meet Bill Casey of the CIA, after a cock-up which implied that the dinner was at Grosvenor Square. After I had dismissed the car, I had to take a taxi to Winfield House. Casey seemed a bit more intelligible than usual; on a previous call on Geoffrey Howe, during my time as DUS for Defence and Intelligence, we had to ask the American embassy to tell us what he had said; they agreed to an exchange of draft records, if only because they had found the usual difficulty of hearing Geoffrey Howe. It was said of Casey that he had for so long been involved in intelligence that he had learned to speak in cipher. I thought it an interesting, and sad, reflection on the UK–USA intelligence relationship that two of Casey’s aides cut the dinner for a German function; and that Casey himself described his visit here as ‘en route to Bonn’.

10 JULY 1986

Robert Armstrong called on me this afternoon – a rare occasion nowadays for the Cabinet Secretary to call on the Foreign Office – to discuss the problem of ministers calling in foreign diplomats without telling the FCO, as Tom King had just done. I had been involved in a slightly different problem during the Falklands War, when the Air Force in the Ministry of Defence had made covert contacts with the air attaché in the Chilean embassy, without informing us. I later received an apologetic visit from the head of Defence Intelligence, Lieutenant General Sir Maurice Johnston (an Old Wellingtonian who had been in my father’s house, and who later turned up as a fellow officer with me in the 40th Field Artillery in Dortmund, before defecting from the Gunners to a smarter regiment, the Queen’s Bays).

As for Cabinet Secretary calls, I recall that during my time as private secretary to Paul Gore-Booth, he and Sir Burke Trend regularly exchanged calls – one of which must have provoked Trend’s private secretary, William Reid, to initiate a practice of exchanging doggerel with me – Reid and Wright – a practice which has continued in our retirement. [A recent exchange referred to my exclusion from the Times’s birthday list on my eighty-fourth birthday.] Simon McDonald (who was private secretary to both David Gillmore and John Coles) has confirmed to me that the then Cabinet Secretary never called on the PUS – though my last private secretary, Tim Simmons, apparently insisted on the PUS being put through on the telephone at the same time as Robin Butler, on the grounds that while one was head of the civil service, the PUS was his equivalent as head of the diplomatic service.

A group of Conservative MPs visited the office today for a presentation on the diplomatic service over a sandwich lunch, one of a very successful series which has done something to improve the office’s relationship with Parliament.

11 JULY 1986

Charles Powell confirmed to me today that the Prime Minister is still adamantly opposed to Geoffrey Howe’s ideas on the Falklands. There is now a complicated scenario with the Ministry of Defence, which is very keen to get ministers to decide on force levels, and the need to impose a fisheries programme which Geoffrey is, rightly, reluctant to institute without a parallel diplomatic conciliatory move.

I lunched with John Fieldhouse, and later stayed for a private talk covering the Falklands and Conventional Disarmament, on which the chiefs of staff have been outraged by Geoffrey Howe minuting George Younger on the latter without prior consultation at working level. I left for Ditchley at 4 p.m., having hurriedly minuted Geoffrey on the Falklands.

14 JULY 1986

An early drive to Chevening, for a session of talks between Geoffrey Howe and Eduard Shevardnadze, who arrived by helicopter at 9.15 a.m. Talks round the table in Geoffrey’s study upstairs were mainly on bilateral relations; chemical weapons; Southern Africa; and the Middle East. The time available was halved by interpretation, but it was quite a good dialogue, and Shevardnadze has a ready Georgian wit. Although not recorded at the time, I vividly remember that, in the midst of a discussion on disarmament, a white dove flew through the open window – it was a very hot day – circled the room, and flew out again. I think the Russians must have thought it was some devilish British trick!

In the afternoon, I drove back to London for a brief spell on my in-tray before going to the rehearsal of the St Michael and St George service in St Paul’s. The rehearsal was unnecessarily long, and could have been done in twenty minutes, if properly organised. As secretary (ex officio) of the order, I had to parade directly in front of the chancellor’s page and banner (tickling my head, with the chancellor himself – Peter Carrington – muttering in a Carringtonian way about ‘all this ridiculous ceremonial’).

Geoffrey Howe telephoned me last night to say he had decided not to push his Falklands ideas at the moment, but described the Prime Minister’s attitude to this question as ‘little short of manic’. There was a good profile in this week’s Observer, assuming (as most people do) that Geoffrey is, for the present at least, her potential successor, if she was to fall under the proverbial bus (on which The Observer quoted Peter Carrington’s remark: ‘No bus would dare’).

15 JULY 1986

I am told that Geoffrey really did come very close to resignation last night, presumably on the grounds that the Prime Minister was so far apart from him in her approach to South Africa. The press are becoming increasingly interested in (or inventing) a supposed constitutional crisis between the Prime Minister and the Queen.

16 JULY 1986

An early meeting on South Africa, on which Geoffrey is determined to try to produce a more conciliatory formula, and to get the Prime Minister to accept that we shall almost certainly – I think certainly – have to accept some measures against South Africa at the Commonwealth meeting in August. The Prime Minister is still holding out for no move, or hint of a move, before the Howe mission is over in three months’ time.

Following the meeting, Geoffrey had quite a good session with the Prime Minister, which enabled him to make a positive statement in the House this afternoon. The important thing will be to ensure that the PM does not go back on it at Question Time tomorrow.

Another case today of a senior diplomatic posting leaking, with David Goodall being congratulated by the Chief of General Staff on his posting to India before he knew about it himself – an echo of Norman Reddaway’s experience in the Beirut souk in the 1950s, when he was allegedly congratulated by some Lebanese on his posting as ambassador to Warsaw before the personnel department had notified him.

Robert Armstrong called on me to air his worries about the Commonwealth meeting and a possible constitutional crisis, on which there had been some press speculation, though my impression was that the Palace was fairly relaxed on the subject, attributing worries in No. 10 more to Nigel Wicks than to the Prime Minister herself. Robert suggested that Christopher Mallaby (then on secondment to the Cabinet Office) should do some very private contingency planning with someone (perhaps Tony Reeve) in the FCO.

In the evening, I dined at Lancaster House with the Exports Credits Guarantee Department (ECGD) Advisory Council, sitting next to my host, Alan Clark, the Minister of State for Trade. When I told Geoffrey Howe, who I was dining with, he advised a long spoon. Clark told me that he had always been ‘infatuated’ with the Foreign Office, but that it had been a ‘frustrated love affair’. When he claimed that relations were bound to be bad between the two departments, and were deteriorating, I replied firmly that I had only recently agreed with Permanent Under-Secretary Bryan Hayes (who was present) that relations had never been better.

[Many years later, Virginia asked me what I wanted for my birthday. When I said that I would like Alan Clark’s diaries, she replied that she was prepared to give me anything I wanted, but not them. We had both been extremely angry about Clark’s account of members of the diplomatic service, including his outrageous comment that one of his ambassadorial hostesses (admittedly anonymous, but nevertheless easily identified) proved that people with muscular dystrophy were always the most boring (or words to that effect).

After I had joined the board of BP, I discussed Alan Clark’s diaries with John Baring (Lord Ashburton, the then chairman). John told me he had shared rooms with Alan Clark at Oxford, so knew him well. He commented that, from reading the diaries, you would think the Clarks were a rather grand family. ‘Actually,’ he added, ‘they were merely traders – like the Barings.’]

17 JULY 1986

The Commonwealth Games seem to be crumbling, with nine participants having fallen out so far. My attempt to get the PM to use some positive wording in the House of Commons today (and which could be used to encourage a positive decision from the Frontline States meeting in Harare tomorrow) failed, since Charles Powell took it on himself not to show Geoffrey Howe’s advice to the PM ‘on grounds of tact’.

21 JULY 1986

A call from Ramsay Melhuish (Harare) who is nervous, as a lot of high commissioners should be, that some Commonwealth governments may decide to break diplomatic relations with us over sanctions for South Africa. The walkout from the Commonwealth Games has now reached twenty-four countries.

A meeting this afternoon in Robert Armstrong’s office on intelligence estimates, at which Peter Middleton (Treasury) infuriated us all by looking rather self-satisfied. In fact, he had little reason for self-satisfaction, since the Treasury’s attempts to cut back intelligence expenditure were invariably reversed by Margaret Thatcher, who was a strong defender of all three services [none of which, incidentally, was at this stage avowed].

23 JULY 1986

Geoffrey Howe told me today that he wanted me to be the ‘third man’ at the Commonwealth review meeting on South Africa in August. When I discussed this with Charles Powell, he said firmly that the PM had ‘decided’ that Robert Armstrong should do it (even though she is alleged to have said, after the Nassau meeting, that she did not want him to do it again).

24 JULY 1986

A brief (and rare) call from Jacques Viot, the French ambassador, asking to present a request for agrement for Luc de Nanteuil as his successor. A pity that Viot is going; he has gone down well in London. But French ambassadors in London have never, in my experience, regarded it as part of their duty to cultivate the FCO. I remember that when Michael Palliser was PUS, he once asked all the under-secretaries, at his morning meeting, which of them had received the French ambassador or even a senior official from the French embassy; virtually none of them had. This neglect was not, of course, helped by the general impression that Margaret Thatcher gave to all and sundry that the FCO was an object of contempt. Luc de Nanteuil (le vicomte) turned out to be an even less frequent visitor than his predecessors.

25 JULY 1986

Charles Powell told me today that (allegedly unknown to him and to Bernard Ingham) the Prime Minister had given a private interview to the Sunday Telegraph, who were insisting – in spite of appeals both to the editor and the proprietors – on publishing the South African bits of the interview this Sunday. Charles claimed to be appalled; when I saw the text later, I agreed that it would be thoroughly unhelpful – and more worryingly, could be seen by Geoffrey Howe as another deliberate attempt to undermine him.

28 JULY 1986

I called on Timothy Raison at the ODA, who seems to be very conscious of morale problems in the FCO/ODA relationship. He asked me to try to get Geoffrey Howe to pay the ODA more attention. He also pointed out that the honours list regularly contains a long list of FCO awards, but very seldom any from the ODA.

John Fawcett (Sofia designate) called today. He was later to end his mission with a highly eccentric valedictory despatch, calling for total disarmament. When Geoffrey Howe heard (from Fawcett on his farewell call) that the department had recommended against printing the despatch, he immediately suspected a bureaucratic cover-up, and asked to see the file copy. Having read it, he expressed total agreement with the decision not to print it.

29 JULY 1986

I held an early meeting to coordinate briefing for next week’s Commonwealth review meeting. The main brief will depend on Geoffrey Howe’s talk with the PM on his return from Southern Africa, and on Thursday’s Cabinet. As far as I can tell, most of the Cabinet accept that we have got to adopt, or at least to undertake to adopt, further measures against South Africa. The departmental ministers, such as Transport, are predictably opposed to measures which hurt their interests; but both the PM and Norman Tebbit are still fairly adamant against putting on any extra pressure.

I attended the first half of Tim Renton’s meeting on Arab/Israel with Middle East heads of mission. Having for years thought we should upgrade our contacts with the PLO, I found myself arguing rather strongly that this would be a quite inappropriate and irrelevant time to do so. It would also cause great trouble with King Hussein and President Mubarak.

Robert Armstrong tells me that the PM is not going to accept the move of the ODA to Richmond Terrace, and asked if Geoffrey Howe would drop the idea. I said that I thought it was an outrageous situation, and that the PM should be made to record her decision, the reasons for it, and the specific authorisation for the extra money involved from the Contingency Fund. The Public Accounts Committee could well have something to say about it.

Geoffrey Howe had a bad meeting with the PM today. Ewen Fergusson told me it was quite clear that the prospect of meeting her had overshadowed the entire Africa visit. It has also become government by bully!

In a letter, dated 30 July, to the service, I put it like this:

The Prime Minister’s approach to the whole question of further sanctions or measures against South Africa has throughout been clear and consistent. She believes that sanctions are wrong and ineffective, and that they will serve only to damage our own interests as well as those of the blacks within South Africa and of South Africa’s neighbours. Her argumentation is flawless, but although the words of her pronouncements on this subject may in logic be right, the music has often been open to misinterpretation. The truth is that her statements, like those of President Reagan, have all too readily been seen in Africa and elsewhere as support for President Botha and apartheid. Her own conviction that she is right has made it all the more difficult for the Secretary of State to persuade her that we may have to be ready to move very quickly to some further measures if the pressures become too great. Failure to do so could result in real damage to our interests both in black Africa and more widely.

31 JULY 1986

After a Cabinet meeting which reached unanimous, if unsatisfactory, conclusions on further measures against South Africa, Bernard Ingham appears to have briefed the lobby that Geoffrey Howe had been isolated, and was considering resignation. Geoffrey told me this afternoon that he believed that Bernard was speaking without the PM’s authority.

David Thomas called today to say goodbye on leaving the service. He is leaving early because his wife Susan (a Liberal candidate who later became a Liberal peer as Baroness Thomas of Walliswood) does not want to go abroad again. David himself told me he found the world such a disturbing place that he virtually wanted to ‘get off’. He also wondered whether the PM knew [I didn’t!] that the Assistant Under-Secretary dealing with Latin America for the past three years had been an Argentine subject, as well as the husband of a Liberal candidate. He said that when he had been in Moscow, there were more Argentines in the British embassy than in the Argentine embassy – an extraordinary illustration of the size and diaspora of the Anglo-Argentine community.

1 AUGUST 1986

The lead story in The Scotsman today – Mrs Thatcher is in Edinburgh – quotes a senior FCO source as denying that No. 10 had deliberately misled the press yesterday with the story of Geoffrey Howe’s resignation. Mrs Thatcher rang Charles Powell at 6 a.m., and was said to be ‘incandescent’. Tony Galsworthy told me that Geoffrey had been on the point of writing to the PM to say that either he or Bernard Ingham must go. He did eventually write two personal letters this evening: one, expressing his extreme displeasure over press handling; the other, urging the PM to adopt an emollient stance in her bilateral meetings and at the Commonwealth review meeting this weekend. Charles Powell later assured me that the PM was determined to adopt a calm and conciliatory approach ‘unless provoked’, at least in her bilateral meetings. Unfortunately, the PM is clearly looking forward to a row, and interprets recent opinion polls as showing that the electorate support a tough attitude towards sanctions and Southern Africa. She is probably right!

2 AUGUST 1986

Lunch at Wargrave Manor with Sultan Qaboos, for the PM and Denis Thatcher. Robert Alston (ambassador in Muscat), Tim Landon, the Omani ambassador and Charles Powell were also there.

I had earlier considered with Tim Renton whether the PM should be briefed on the signals we were getting that the Sultan wanted to recover the embassy building in Muscat – in my experience, one of the most beautiful ambassadorial residences in the diplomatic estate – for his own purposes. I decided (mistakenly) not to brief her, on the grounds that the Sultan was most unlikely to raise the subject, and that Margaret Thatcher would be furious if she discovered that Geoffrey Howe had offered to hand it back (in exchange for a prime site on the coast, looking out over the Arabian Sea).

As it was, in the middle of lunch, the PM fixed Robert Alston with one of her glares and said: ‘I hope Mr Alston is looking after that beautiful residence. We want to keep it for a long time.’ She turned her glare on me, and said: ‘Permanent Under-Secretary, you know my views about residences.’ I was extremely embarrassed, as I knew that the Sultan was under the impression that Geoffrey Howe had accepted the idea of an exchange. Robert Alston cleverly retrieved the immediate situation by assuring the Prime Minister that he was looking after the site, and that about eighty workmen had been working on it when he had left Muscat a few days earlier.

3 AUGUST 1986

After dictating several records from the Wargrave lunch, I went to Robert Armstrong’s office to hear Charles Powell’s description of the PM’s bilaterals with Mulroney, Gandhi and Kaunda. The first two had been surprisingly calm and good-tempered; the last was described as ‘fairly disagreeable’.

At the review meeting itself, I spent most of the day waiting around at Marlborough House and doing a certain amount on my box. I arranged with my old Indian colleague from Damascus, Venkateswaran, to lunch with him tomorrow, since Gandhi had hinted fairly strongly to Tim Renton that our bilateral problems were better discussed without the involvement of their Foreign Minister. I suggested to Venkat that our lunch should be à deux, since his deputy, Daulat Singh, is virulently anti-British, and probably a major cause of our current difficulties.

The review meeting broke up soon after 6 p.m., and I was asked to join a wash-up meeting in the PM’s study at No. 10. A standard performance by the PM of either glaring at or ignoring Geoffrey Howe, whose patience must be wearing pretty thin. At one point, when she was being particularly rude to him, he simply picked up his red box and started doing signatures. This threw her for a moment; but then she quickly turned her fire on me!

Alan Watkins in today’s Observer described Geoffrey as ‘Mrs Thatcher’s Challenger’, which won’t have helped him. She again started talking about partition as a solution to South Africa. I just hope she does not try this out as an idea at the review meeting. All her (and Denis’s) instincts are in favour of the South African Whites. She described today’s meeting as ‘worse than Nassau’.

4 AUGUST 1986

Much of today was spent hanging about in Marlborough House, waiting for reports on the meeting from Robert Armstrong and Geoffrey Howe. In spite of an apparent determination to play it cool, the PM started disastrously with an abrasive statement, saying that Britain was an independent state, and would not give aid to help the military struggle (though no one had suggested that we should).

I gave lunch to Venkat, in view of Gandhi’s hint about avoiding ministerial discussion, though it has since occurred to me that it may have been designed to bypass Tim Eggar as much as the Indian Foreign Minister, Shiv Shankar, since Tim had an extremely rough meeting with the Indian High Commissioner two weeks ago. Venkat was very critical, both of Eggar and of our High Commissioner, Robert Wade-Gery, but agreed that Daulat Singh was not helpful, and claimed to have just blocked a long letter which Singh wanted to send.

5 AUGUST 1986

The Commonwealth review meeting having ended at midnight, I had left a free morning in my diary. Geoffrey Howe held a meeting at 11 a.m. to discuss what work was needed, including messages to all and sundry explaining the outcome. There was a general consensus that the meeting could have gone worse, but that we are not out of the woods, particularly on air links, where British Airways may well find their over-flying rights in Africa removed from them. But the immediate prospect of breaks in diplomatic relations seems to have receded.

Ramsay Melhuish later gave us a vivid description of the non-aligned rally in Harare, where Mugabe was giving a spirited call for sanctions against South African flights, when his voice was completely drowned out by the roar of a South African Airways flight taking off from Harare airport for Pretoria! If British Airways divert round the bulge of the African continent (which they will soon be able to do with their new aircraft) there is a strong risk of retaliation against their flights elsewhere, including India and Malaysia.

6 AUGUST 1986

Percy Cradock called, and opened the subject of the PM’s attitude to the office, which, as he put it, loses nothing in the way in which her comments are passed on by Charles Powell. I doubt whether Charles expends much effort on the sort of literary contortions that I went to at No. 10 in translating brusque, and sometimes obscene, comments on papers into phrases like: ‘The Prime Minister has expressed some reservations…’ [Bill Harding, who had been one of the deputy under-secretaries, later told me that, on his farewell call on the Prime Minister, she kept him for a quarter of an hour without any comment on the service, other than remarks about the need to find good posts for young people ‘like Charles Powell’ (who was present throughout).]

7 AUGUST 1986

I called on Lady Young before going on leave. She is clearly nervous about being left in charge of the office, particularly with the South African problems, on which she once made an unwise speech, for which she was rebuked by Geoffrey Howe.

David Goodall reported to me that Robert Armstrong had told him that Geoffrey Howe had passed him a note during the Commonwealth review meeting, while the PM was speaking, saying: ‘I suppose there may be more unhelpful ways of presenting our case, but I can’t think of them.’

1 SEPTEMBER 1986

I returned from holiday in Salcombe today, during which I read the memoirs of two predecessors, Lord Hardinge and Sir Alexander Cadogan. (The latter was the subject of one of the more remarkable coincidences I can remember. When visiting Hatchards, I had asked the shop assistant whether Cadogan had written his memoirs. A lady standing next to me said: ‘Yes, indeed he did. I am his widow.’) I was struck by the extent to which Hardinge (who was appointed Viceroy of India during the First World War, and then returned to a second stint as PUS) was treated as a courtier, accompanying King Edward VII on numerous trips abroad, in place of ministers; and by the amount of drafting that Cadogan did for both the Foreign Secretary and Prime Minister on the basis of telephoned instructions, and with apparently very little back-up from the office.

Geoffrey Howe held an office meeting today to prepare for a ministerial meeting on visa regimes for Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Ghana and Nigeria, under pressure from the Home Office, following bad congestion at the airports here. Christopher Mallaby later reported to me that Geoffrey Howe had been totally isolated at the ministerial meeting (widely trailed by press leaks), and had to give way to a decision to impose regimes ‘at an early date’. When I saw Geoffrey later, he was gloomy about it, and rather predictably casting around with criticisms of the office. But he commented that the PM seemed to be taking a harder and harder line on racial questions. The opposition have already attacked the measures as ‘racist’.

Charles Powell looked in at 11, with a very disapproving message from the PM about a Daily Telegraph story alleging direct quotations from FCO officials on the visa regimes. I said that I thought it most unlikely that any diplomatic service officer had spoken as alleged, but pointed out that the story was only the culmination of three days of extremely unhelpful, and anti-FCO, press briefing. Charles said that the PM was aware of this, and suspected the Home Office (Bernard Ingham is away at present).

Geoffrey Howe spoke to me again today about the alleged anti-feminine bias in the administration (having spent part of his summer holidays with Pauline Neville-Jones). He also raised several instances in which Robert Armstrong had minuted to the PM on foreign affairs questions without adequately consulting him.

3 SEPTEMBER 1986

There was a ridiculous editorial in today’s Sun about visa regimes, referring to pin-striped FO officials worrying about their tiffin and cocktails. Christopher Meyer put up a robust draft letter, in Sun-style, for Geoffrey Howe to send to the editor.

The German ambassador called at 4 p.m., presumably to discuss my visit to Bonn and the forthcoming summit. It turned out that he did not know about the first, and his instructions were five days out of date on the second. Not very impressive; he was visibly embarrassed.

7 SEPTEMBER 1986

Lunch with the Callaghans at Ringmer. Jim has delivered his memoirs to his publisher for launching next April, commenting that I might have to vet them officially. He thought there might be a difficulty over his account of Guadeloupe; but added that Helmut Schmidt and others had already produced their accounts, and that Schmidt had, in his view, given a very inaccurate account of the meeting.

8 SEPTEMBER 1986

I lunched with Ray Seitz (then the no. 2 in the American embassy), who gave an interesting account of the problems facing the US Foreign Service, in which over 50 per cent of ambassadorial appointments are now political. [An interview in the Financial Times on 7 November 2015 with Bill Burns claims that he had retired from the United States government after a 33-year career ‘as only the second career diplomat in US history to have made it that high in the Department’. Since much of these diary extracts must appear very critical of Margaret Thatcher, I should mention, in her favour, that there were no political appointments to embassies or high commissions during her time as Prime Minister; and the plethora of political advisers was only to blossom when Tony Blair arrived in No. 10.]

9 SEPTEMBER 1986

Robert Armstrong told me today that the PM has given way (with extreme ill grace) on the move of the ODA to Richmond Terrace, in the face of a warning minute from Robert that the Public Accounts Committee might wish to delve into the reasons for extra expenditure of £3–4 million. He thinks she will only give up after a ‘bloodbath meeting’ at which Geoffrey Howe will be exposed to maximum flak (and attacks on alleged FCO misuse of the old Home Office building). Robert again commented that the tone of the PM’s anti-Foreign Office feeling was very strident, and not exactly countered by Charles Powell.

Virginia and I dined at ICI, for their annual dinner for permanent secretaries, with Denys Henderson as host. I am not sure if it was at this dinner, or a subsequent occasion, when Denys, or his successor, walked me down the corridor, along which were portraits of all previous chairmen, and told me that when Margaret Thatcher had similarly come to dinner, she had ticked off each portrait with the words: ‘He wasn’t bad,’ ‘He was dreadful,’ and so on.

12 SEPTEMBER 1986

An awkward situation has arisen today over sanctions. Hans-Dietrich Genscher telephoned Geoffrey Howe to say that Helmut Kohl was adamantly against sanctions on coal. This puts the whole package of Hague measures into confusion, just at the moment when the US Congress has reached agreement on a stronger package. It will tempt Margaret Thatcher to unravel the whole thing, particularly when the Frontline States themselves are backsliding fast on sanctions. Geoffrey himself thinks the situation is manageable, since dropping coal will certainly lead some community colleagues to press for sanctions on vegetables and fruit, which the PM is adamantly determined to block.

17 SEPTEMBER 1986

I had an hour’s meeting with Geoffrey Howe to prepare him for his public expenditure bilateral with the Chief Secretary on 19 September. We may have some difficulty stiffening him, since he let the office down badly two years ago. There may be some psychological problem of the Chancellor poacher having turned Foreign Secretary-gamekeeper – just as I later faced problems with Douglas Hurd, as a diplomatic-service-officer poacher having turned ministerial-gamekeeper.

When John Major was (to his surprise) moved by Margaret Thatcher from being Chief Secretary to Foreign Secretary, I asked him whether he knew what the Treasury brief was for the diplomatic service and he claimed that the only brief he had looked at was the Transport brief, since he had been convinced that if he was moving anywhere it would be to Transport.

Television last night showed the PM in Bonn, gratuitously drawing attention to her opposition to sanctions, and ridiculing the idea of ‘signals’ to South Africa at precisely the moment when Geoffrey Howe had put together a reduced package in Brussels and was telling the press that it would be a clear ‘signal’ – having successfully left the onus on the Germans and the Portuguese. [A foretaste of Margaret Thatcher’s later undermining of John Major at the Commonwealth heads of government conference in Kuala Lumpur three years later.]

18 SEPTEMBER 1986

Geoffrey Howe rang me at 1.30 a.m., with a complicated request for advice on a Soviet swap. I first of all did not realise who Geoffrey was; and then found it very difficult to understand what the question was. No doubt it will be clear tomorrow. [It did, indeed, transpire that it was an American proposal to include Oleg Gordievsky’s family in a deal with the Russians.] Geoffrey asked me whether it was a capital offence to telephone PUSs in the middle of the night, and said that when he had done the same to the Chief Secretary, and apologised the next day, the Chief Secretary had totally forgotten that he had telephoned, or why!

[Geoffrey’s habit of telephoning people at unsocial hours led to an amusing incident which Nick Browne recounted at his farewell party from Middle East Department for Tehran in early 1997. His young son had come into his bedroom at 6.30 a.m. one morning on April Fool’s Day to say that Sir Geoffrey Howe was on the telephone and wanted to speak to him. Nick – assuming this to be an April Fool – said: ‘Tell him to bugger off.’ The son returned a few minutes later, saying: ‘I told him to bugger off; but he says that he still wishes to speak to you.’]

20 SEPTEMBER 1986

Virginia and I drive to Chequers for the Prime Minister’s lunch for King Hussein and Queen Noor. One rather tiresome guest (an American wife) told me loudly that she ‘didn’t think people should marry wogs’ – obviously taking pride in shocking people. This reminded me of a call I received, as head of Middle East Department in the early 1970s, from the Saudi ambassador, Abdulrahman Al-Helaissi, to ask if I would be offended if someone called me a wog. I told him that I would be even more offended if he had been (as he clearly had), but that the origin of the expression was said to be an abbreviation for Westernised Oriental Gentleman, and therefore not intrinsically offensive.

There was a brief discussion after lunch about the strategic importance of the Gulf and the Cape route, on which Peter Carrington was splendidly direct in telling the PM that the latter depended on which war you were fighting. As NATO had only fourteen days of ammunition to fight a war, he thought that the sea route via the Cape for any strategic materials was going to be a bit slow.

Elspeth Howe asked me if I could arrange for Geoffrey to visit Jordan, to which I replied: ‘How much is it worth?’ In reply, she promised not to raise the position of women in the service for a whole week.

23 SEPTEMBER 1986

I gave lunch to Nigel Wicks, who thought that the PM was even more anti-FCO since her holiday than before. He commented on Geoffrey Howe’s poor showing in Cabinet, but thought that the PM’s antipathy was primarily a difference of philosophy from his, and resentment of the FCO’s attachment to compromise and consensus (although he made the familiar comment that she has little quarrel with such individual members of the service that she meets).

26 SEPTEMBER 1986

I called on Janet Young for a round-up, mainly on staffing questions, including morale and recruitment, on which she is very keen to help and has the right ideas. The sad fact is that she has little clout with Geoffrey Howe, and even less with other ministers.

A flood of weekend papers tonight. My ration could just be squeezed into one box. Geoffrey Howe had four – and loves it! (I later reported that he had returned from New York, having demolished six boxes.)

29 SEPTEMBER 1986

Geoffrey Howe held a meeting on Hong Kong, on which he is likely to find the Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Governor of the Bank of England in opposition to him. He is also fighting a lone battle (with Tom King) on the question of three-man courts in Ireland. But he seems to thrive on it all.

A launch party this evening at George Weidenfeld’s for Paul Wright’s book A Brittle Glory, at which Lord Chalfont told the story of the beaver at the foot of Beaver Dam telling a friend that someone else had built it, but it was based on his idea.

7 OCTOBER 1986

In a discussion with Geoffrey Howe about James Craig’s leaked valedictory despatches (it having emerged that several newspapers, including the Financial Times and The Independent, had copies), Geoffrey, rather characteristically, tended to be critical of James’s rudeness about the Arabs, and the unwisdom of being that frank in government documents. He even tried to get me to warn heads of mission to be more careful in their drafting. I refused, on the grounds that it would be quite wrong to curb any member of the public service from giving frank advice, however unwelcome.

8 OCTOBER 1986

An injunction on the Craig despatches was granted this morning. I received a telephone call at 1.30 a.m. from the resident clerk [who identified himself many years later as Charles Crawford, after Matthew Parris’s parting shots had included one of the despatches in 2011] to say that the Glasgow Herald was printing both despatches and was about to release them. After I had contacted John Bailey, the Treasury solicitor, a judge was found in Edinburgh prepared to issue the Scottish equivalent of an injunction, which had to be driven – in a coach and four? – to Glasgow at 4.30 a.m. By that time, of course, hundreds of copies of the Glasgow Herald were already on the streets.

I agreed with Robert Armstrong this evening that the police should be called in to investigate the leak. Anthony Loehnis telephoned me from the Bank of England to say that one of the journalists who interviewed James Craig (called Forbes) was an ex-Bank of England man; and that the bank had discovered (very efficiently) that Forbes’s signature was on the official receipt of the despatches.

Two days later, I was asked to call on the Attorney General, Sir Michael Havers, at the law courts. As I had a credentials appointment at Buckingham Palace later that morning, I had to go in diplomatic uniform, telling Sir Michael that I was merely trying to uphold the dignity of the FCO – which the Daily Mirror claimed this morning was the reason for all this fuss about a leaked despatch. I also had a further conversation with John Bailey, who told me that The Observer was now claiming that the full text of the offending despatch was not only available to the Saudi embassy; it was also being carried extensively both on agency tapes and on Israeli radio.

I commented: ‘The press have behaved unspeakably this week. It is not as if there is any particular principle they are trying to defend.’

13 OCTOBER 1986

My morning meeting of under-secretaries was largely taken up with the Reykjavík summit, and the implications of Reagan’s stated hopes for the abolition of all nuclear weapons within ten years. This will cause considerable alarm, both in the Quai d’Orsay and in No. 10.

21 OCTOBER 1986

The PM chaired a meeting today to discuss the Hindawi trial, and decided, with only Tim Renton putting up a contrary argument, that we should break relations with Syria. I met a rather disconsolate Tim afterwards, who said that he had received no support from other ministers. I imagine that the expulsion of Haider might well have led to a break anyway; but this is bad news, and we are already thinning out our embassy in Beirut (a fact that unfortunately leaked in the press today).

22 OCTOBER 1986

Geoffrey Howe returned from Hong Kong this morning and held two office meetings – one on arms control and one on Syria, on which he is dismayed by the ministerial decision, but has concluded that there is no hope of changing minds – an appalling case of decision by intimidation. A verdict on Hindawi is now expected tomorrow, and it is not excluded that he may be acquitted. Geoffrey (as an ex-lawyer) commented this morning that it was a case that he would have enjoyed defending.

A meeting at 6 p.m. with Robert Armstrong and others to consider his draft brief for the PM’s meeting tomorrow on Richmond Yard; but the meeting was interrupted by a dramatic intervention from Nigel Wicks, who arrived to tell us that the PM had agreed after all that the ODA move should go ahead, and that her meeting had therefore been called off. The PM has however demanded an assessment of the FCO’s use of the main office buildings, on which she clearly has a vision (or has heard reports) of extravagant and wasteful use of them. But at least one piece of bloodshed has been saved.

23 OCTOBER 1986

The Hindawi jury failed to reach a decision today, but will presumably do so tomorrow. Geoffrey Howe was recorded in a letter from No. 10 as having ‘agreed totally’ with the decision to break relations, which is strange; but presumably he decided that if he was not going to try to reverse the decision, he had no other option.

24 OCTOBER 1986

Sherard interrupted my talks with the Austrians by passing me a note at noon, to say that Hindawi had been found guilty, and sentenced to forty-five years. The Syrian ambassador would be in the office at 12.50 p.m. When the time came, I saw Haider, with Patrick Nixon, in the waiting room, and virtually read out a speaking note, ordering him and his staff out of the country by 7 November. Haider responded by saying that he had expected this, but assured me that he was totally innocent of any involvement. A very frosty and unpleasant interview, and I left it to Patrick Nixon to see the ambassador out. I learned later that Haider had made some pretty offensive personal comments about me to the press [recorded by Sherard Cowper-Coles in his 2012 book, Ever the Diplomat].

Charles Powell called, mainly to discuss the PM’s Washington visit, because of which she has overturned Geoffrey Howe’s advice that we should vote for the Nicaraguan Resolution at the United Nations.

29 OCTOBER 1986

On my way to lunch with Greville Janner at Veeraswamy, I bumped into Michael Heseltine. Assuming that I was still in Saudi Arabia, he asked how the Tornado deal (which he had signed) was going. When I told him that I was now PUS, he exclaimed: ‘Good God! You’d better not be seen talking to me, then,’ – a reference to his walkout of Margaret Thatcher’s Cabinet over the Westland affair. When I told Greville Janner this, he commented that it would surely do my career much more harm to be seen lunching with him!

30 OCTOBER 1986

I pulled Geoffrey Howe’s leg about a letter from the Financial Times, revealing to me that Geoffrey had given them a copy of a despatch from Belgrade, and suggesting that there should be a Howe award for the best official document of the year. In the light of the Craig despatch row, I told Geoffrey I would keep the letter, and use it in evidence against him, but wouldn’t put it in the hands of the Director of Public Prosecutions for the moment.

1 NOVEMBER 1986

My relations with Tim Eggar are slightly strained, since I had to draw his attention to the undesirability of including officials in party political discussions about electoral registration.

4 NOVEMBER 1986

Charles Denman reported to the office today on a fascinating talk with Zaki Yamani (who was sacked as Saudi oil minister last week), and who told Charles that two ministers had wished to issue a statement of solidarity with Syria over the Hindawi affair, but had been shouted down by their colleagues. Yamani himself said that he was 200 per cent in favour of what HMG had done, and congratulated us on having the guts that his own government lacked.

6 NOVEMBER 1986

Credentials for the new Romanian ambassador (under a changed name), who turns out to be the one Romanian at Harold Wilson’s lunch in Bucharest in 1975 who took his coat off in the summer heat, explaining to Ken Stowe that this was because he was the only Romanian at the table who was not carrying a gun.

This afternoon, I attended a wreath-laying ceremony by Geoffrey Howe at the diplomatic service memorial in the main entrance hall. It is a sad coincidence that two of the three members of the service who were murdered by the IRA – Christopher Ewart-Biggs and Richard Sykes – were both pupils of my father at Wellington College. Both their names appear on a similar memorial in Wellington Chapel.

10 NOVEMBER 1986

Lynda Chalker called on me this afternoon to ask about Robin Renwick (whose help in European Community (EC) matters she is obviously terrified of losing) and about Pauline Neville-Jones.

11 NOVEMBER 1986

An early meeting with Geoffrey Howe, at which he complained about alleged inactivity by the office over Chirac’s extraordinary intervention in the Washington Times about Syria and hostages, accusing British Intelligence reporting of being garbage, and discussed Robert McFarlane’s arms deal with Iran. I defended the quality of reporting on both subjects from Paris and Washington, but agreed that more thought should be given to what we should say to both the Americans and the French.

Geoffrey also complained about the briefing provided for the ministerial meeting on AIDS, pointing out that it urged ministers to reach early decisions, but gave no guidance on what those decisions should be. A fair point, though Geoffrey tends to whinge when he is uneasy about things. [I had already noted that the Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS), now under my former No. 10 colleague Ken Stowe, had made a surprisingly poor showing at Robert Armstrong’s preliminary briefing meeting.]

12–16 NOVEMBER 1986

My visit to Washington, which coincided, from 14 November, with the Prime Minister’s visit. Both visits were conducted against a backdrop of the arms for Iran scandal. At lunch with Mitch and Mary Ellen Reese on 15 November, Mary Ellen commented to me that the whole arms for Iran scandal could have come out of one of her own spy novels. When I called on Bob Gates at the CIA, I told him that I had hoped to call on Rear Admiral Poindexter, but that the meeting had been cancelled. Gates told me I was in good company, since both he and Bill Casey had been similarly put off.

At a private dinner that evening in the embassy, Margaret Thatcher was in a good mood (except for one point, when she was reminded of the FCO building, on which she is slightly mad). She talked about her succession to the leadership, claiming (rather implausibly) that it was all a matter of chance, and that Keith Joseph would have had the leadership if he had wanted it.

17 NOVEMBER 1986

On my return, I called on Geoffrey Howe this evening to find him agonising