19,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Suhrkamp Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

“Berlin is damned forever to become, and never to be.” Scheffler could not have anticipated that his dictum would prove prophetic. No other author has captured the city’s fascinating and unique character as perfectly. From the golden twenties to the anarchic nineties and its status of world capital of hipsterdom at the beginning of the new millennium – the formerly divided city has become the symbol of a new urbanity, blessed with the privilege of never having to be, but forever to become.

Unlike London or Paris, the metropolis on the Spree lacked an organic principle of development. Berlin was nothing more than a colonial city, its sole purpose to conquer the East, its inhabitants a hodgepodge of materialistic individualists. No art or culture with which it might compete with the great cities of the world. Nothing but provincialism and culinary aberrations far and wide. Berlin: “City of preserves, tinned vegetables and all-purpose dipping sauce.”

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 271

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Bitte schreiben Sie uns Ihre Meinung per E-Mail an [email protected] oder per Post an den Suhrkamp Verlag, Torstraße 44, 10119 Berlin

Sie sind damit einverstanden, dass Ihre Meinung ggf. zitiert wird.

LESEEXEMPLAR

Bitte keine Rezensionen vor dem 07.08.2021

Jede Form der Weitergabe und Vervielfältigung ist untersagt.

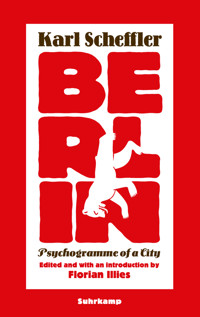

Titel

Karl Scheffler

BERLIN

Psychogramme of a City

Edited and introduced by Florian Illies

Translated by Michael Hofmann

Suhrkamp

BERLIN

Psychogramme of a City

Übersicht

Cover

Informationen zum Buch

Titel

Inhalt

Impressum

Hinweise zum eBook

Inhalt

Cover

Sperrvermerk

Titel

Inhalt

Foreword:

Destiny as Opportunity. On Karl Scheffler’s DNA analysis of Berlin

BERLIN Psychogramme of a City

On Method

Development as Destiny

The Colonial City

The Inhabitants

The Nobility

The Ethos of the City

City of Bourgeois and City of Nobles

The Layout of the City

Building

The Arts

Society

Social Forms

City Culture

Metropolitan Destinies I

The Metropolis

The Population

Wilhelm II

Trade

The New Suburbs

Founder’s Architecture

The Arts

Nature and the Environs

Society in the City

Influence on the Reich

Metropolitan Destinies II

The Pioneer Will

Utopia

The Destiny of Berlin

Informationen zum Buch

Impressum

Hinweise zum eBook

Foreword:

Destiny as Opportunity

On Karl Scheffler’s DNA analysis of Berlin

The last opportunity to cut Berlin adrift was lost in 1648. At the conclusion of the Thirty Years' War, when there were precisely 556 households remaining in one half of the city (Berlin) and 379 in the other (Kölln), there was apparently serious debate among the inhabitants about pulling up sticks and quitting. Unfortunately, they decided against.

Unfortunately? Yes, of course. If you read Karl Scheffler’s bilious love letter to Berlin from the year 1910, you will understand that Berlin will never find its way to itself because, just as in a Greek tragedy, the inability to do so is a condition of the city’s being. To remain in the realm of myth, if Berlin is the illegitimate offspring of a Greek god and a mortal, then the father is probably Dionysus while the mother works in an alien registration office somewhere in the West of the city. And if all that seems a little far-fetched to you now, then try reading this foreword a second time after finishing the book. Because anyone who has skimmed even two or three pages of Karl Scheffler’s analysis will see that the subtitle “Psychogramme of a City” is rather more than a journalist’s high-toned pretension. Scheffler was the first author to explain why there is no escaping Berlin’s destiny. That’s why in his last sentence he declares that Berlin is: “Damned always to become, and never to be.” At the end of 200 pages, that “damned” strikes home like a dagger, covering the arc from Greek mythology to Bahnhof-Zoo in seconds.

But even without the “damned”, Scheffler’s condemnation made a hit in the literary salons of Charlottenburg, Dahlem and Pankow – audible whenever a groan went up over a new building site in Berlin Mitte. With it, though, with the pitiless, indissoluble chain linking it to destiny, it acquires the depth that induced Scheffler to end his book with it, to set it at the conclusion of his anguished meditation. It is the distillation of 200 pages and two millennia. It makes a wonderful aphorism, eight words – and yet it only deploys its full force if you have read the preceding pages. Rarely is it given to the reader to witness an observer like Scheffler at work as in this book, just as rarely to follow a method through to its conclusion as when he draws his inferences from the balled-up history of the city, this metropolis that began as a settlement of German peasants and Wendish fishermen.

The upsetting understanding Scheffler has arrived at from his intense engagement with Berlin is this: that Berlin was always a colonial city, a city of immigrants, repeatedly becoming an object of desire, for Huguenots and draft dodgers, for Silesian weavers and Swabian start-up merchants. When Mark Twain in 1891 enthusiastically commented on the occasion of his first visit to the city (then just 650 years old) how “new” this city was, “the newest city I have ever seen”, even though he was coming from the U.S., where one city after another was being founded – that goes to show how powerful its image is. The news ticker is of course a Berlin invention. Nowhere is there a stronger obsession with the now; the “regime of real time” (David Gugerli) that has governed temporality since 2000 found its crystallization point in Berlin. Scheffler tells you how this cult of the new came to be established in Berlin. What he understood in 1910 holds true more than a century, two world wars and four German constitutions later. They used to come in horse-drawn coaches, now they come by easyJet – the promise still holds true. It’s the hidden engine of this mindlessly propulsive city. Only in Berlin are the questions “Are you still living there then?” or “Are you still at that job?” asked with that tone of surprised contempt. The status quo here is always dodgy, and essentially only exists to be overturned. When galleries of contemporary art threaten to run out of ideas, they open “new spaces” in Berlin, as though that was any sort of substantive answer. Readers of Scheffler’s book will understand why Berlin is the city of “projects”, “development spaces” (of which the “five-year plan” is only the East Berlin variant), why this city is so proud of being a “laboratory”, why visions flourish here the way whole economies do in other places. There is hardly any productive work done here, but all the more gym workouts, working on and out of relationships, working up of the past. The only thing to boom in Berlin is the IT sector, because that’s the one space where imagination is a criterion and not some bourgie annual turnover numbers. And of course there’s no better place to make films than here, where the name of the project is projection. So besotted is the city with possibilities and so uninterested in realities that even the bakers are called “Brot & Mehr” and the 24-hour kiosks “Internet & Mehr”. Whatever it is, it’s never enough. Or if you like: “to be continued, beyond the horizon” (Udo Lindenberg).

Karl Scheffler dubs the people who come to Berlin “pioneers”, and you can tell not much has changed when the city’s marketing department greets newcomers at the city limits with a sassy “Be Berlin”. In German that means: dream on. If New York is the city that never sleeps, Berlin is the city that never wakes up.

Hipness is the manna that this city & more pours out to all and sundry like the 100 Deutschmarks of “welcome money” of yore. Over the centuries, Berlin was the destination for Huguenots and freethinkers, religious liberals and Jews, because this is where they were guaranteed “freedom of conscience”. That’s the secret core even today, even if such freedom is no longer confined to matters of religion. And that too is something Karl Scheffler sensed in his psychogramme of Berlin: “Religious rationalism in the coolly Protestant Berlin asked after the whys and wherefores for so long till the priest saw himself obliged to make his replies semi-philosophical” [p. 23]. In the meantime the other half has gone secular as well, and so Berlin’s answers to the question “Why?” are half philosophy, half mixology. The answer is: just because. Or, as Scheffler puts it: “Hegel’s doctrine that everything that exists is reasonable can be parsed as a sort of Prussian self-diagnosis or affirmation” [p. 27]. But then mere existing never counted for much in this city, where people’s preferred abode is the day after tomorrow. The old nickname “Athens-on-the-Spree” is not a joke, but a deliberate attempt to deceive.

Berlin, the heart’s desire of the pioneers, is most itself, most the colonial city, when it is permitted to be promising. Because when it comes to delivering, Berlin always fails. If we had all read our Scheffler earlier, then we could have spared ourselves the waiting for that “Berlin novel” that was expected any time after 1989, or we would have known in advance that the odds were stacked against a timely opening of the new airport.

Another one of Scheffler’s lessons is that one mustn’t hope that traditions will be respected in Berlin. The only tradition that is maintained is that of having no traditions. The fact that this book was lost from sight for so long is the best proof. Berlin – Psychogramme of a City is such a clever book not least because its author thought through it all himself, from beginning to end. Probably no one gave so much of himself to Berlin as this man, who crisscrossed the city, followed its axes and despaired because they lost themselves in the void, traced its rivers and was in despair all over again, because the city has no interest in its waterways and “the inhabitants don’t show any tenderness for their river, as they do in Paris and Vienna, and Hamburg and Frankfurt am Main” (wonderful observation) [p. 34]. Obsessed as the city is by speed, it reserves such tender feeling as it has for its traffic flows, the S-Bahn lines, the proliferating trams – and the noisy six-lane avenues on whose soft shoulders one sets out wooden tables and, after yoga, eats one’s organic steak from Uckermark. That would be entrecôte Scheffler.

Incidentally, Scheffler never waxes more furious than when he’s on the subject of city planning and architecture, there he’s in his element, the great cultural critic. He almost forgets to breathe for so much “ugliness”, and yet he always manages to raise himself to fresh tirades against the chaos of the planners, the futility of the roads, the monotony of the new districts to the East (Prenzlauer Berg, Mitte). Scheffler insistently lays his finger on the wound – there is nothing natural about this city, no annual rings like a tree, it consists of sporadic random outgrowths (which is why it can’t be a place for truly great culture). Scheffler shows why the heroic figures of German civilization, Goethe and Schiller, Beethoven and Bach, gave Berlin a wide berth, and why it wasn’t by chance that Kleist ended so tragically here: “Certainly, Kleist would have remained profoundly ununderstood anywhere in Germany, but nowhere would the hopelessness of his situation have struck him quite so hard as in the city of a confirmed lack of imagination” [p. 55]. Even Schinkel isn’t enough to get him to make his peace, because this great spirit ultimately fell victim to the DNA of Berlin too: “In his way, he is a genius, but chiefly within the estimation of the inhabitants of the colonial city” [p. 56].

Scheffler was a physical flaneur through the streets of Berlin, but he also browsed through the history of this strange city, passing it through the fine mesh of his analysis until he knew every grain of sand. That’s how this book came about. If you think about it, it’s not even surprising that it works as a guide to the mental landscape of the Berlin in 1910, but functions just as well in dealing with the puzzles of a century later. Because Scheffler explains in his book that the DNA of Berlin, which he was the first scientist to map, was also bound to govern the city far into its future. By describing the curiosities of the place in such minute detail, one chromosome at a time, he describes in little sidelong glances the secret codes of Dresden, Hamburg, Munich, Gdańsk and London. Thanks to Scheffler we learn to see that every city is an individual, with a feel, a temperature, a smell all its own, composed over hundreds of years by the mutual action of geography, rulers, culture, society and tradition.

Scheffler’s analysis takes us through an astonishing array of aspects and perspectives to conclusions of impressive and disturbing clarity: why the Berliners are incapable of building an aesthetically pleasing square (and Potsdamer Platz and the excrescences round the new Central Station bear him out); why Adolph Menzel might have been a world-class painter if he hadn’t had the misfortune to live in Berlin; and why it takes a hermit type like Botho Strauss to stick it out in the rural province of Uckermark, the “steppe that seems to extend all the way into Russia … In melancholy solitude, the farm- and heathland rolls on forever” [p. 13]. You can take this old book and use it as a guide to contemporary Berlin. Even in places where you think you are drowning in history, contemporary Berlin flashes out its excited “me too!” associations. Say in the place where Scheffler explains that sooner or later the Berliners will knock over everything (houses, heroes, kingdoms) except the military, and you think, well, that may have been the case once, and then you remember the weird spectacle at the annual Love Parade on the Grosser Stern, when the settler city was in its hip, nude element and grooved past the statues of the great Prussian generals. Even the Victory Column, the “Siegessäule”, doesn’t put anyone in mind of the War of 1870 anymore, but – if there’s any mindfulness at all – only of the cheering crowds after recent German soccer triumphs and the so-called “Fan Mile”.

Still more penetrating is Scheffler’s analysis of the way the people continually reinvent their rulers: “The populace subtly influences the psyche of its rulers and sees itself reflected in them” [p. 21]. Writing in 1910, Scheffler intended a little jab at the Berliners’ success in revising the Prussian rulers downwards from Frederick the Great to WilliamII. But when one reads how Scheffler identifies “sense of duty”, “objectivity” and “hard realism” as the principal virtues of the Hohenzollerns, you can’t help but see how the Berliners were able to see themselves in the East Elbian Angela Merkel – and not just that, they persuaded the rest of the country, the Bavarians, the Rhinelanders and the Hamburgers to do so as well. The architecture of the former official seat of the Hohenzollerns, the castle, is dissected by Scheffler. The fact that now, behind the reconstructed Baroque façades a “centre of world cultures” has been created, combining the ethnological holdings of various museums, in which the President of the Foundation of Prussian Culture announces “the world should come here to take a look at itself” – that might have got a snort of derision out of Scheffler. Rarely has Berlin’s megalomania (posing as humility) been better held up to view than in this “vision”; rarely has the proletarian desire to play the big man been more plainly exposed than in the plans of the city government to set aside a few rooms for its favourite subject “global.city.berlin”. Dot. Dot. Dot. The colonial city of Berlin is unmistakably there in its gift of itself to the new colonialism, dressed up as some preposterous Third World café. Where what is held up to the world’s admiration is not the world, but Berlin’s monstrous self-infatuation. But please, Scheffler would soothe us, spare the outrage, this is all spelled out in the genetic code of the city.

Don’t, dear readers, be afraid of this book. Just as good as the passages about the irreducible colonial city are Scheffler’s outbursts against the colonial lack of discrimination of Berlin’s bread, which “made eating a sort of necessary evil”. Or my own favourite sentence: Berlin is “not the proud manifestation of a city’s sense of itself but a project of its building industry”. “Make it your project” – precisely Scheffler’s thesis – was the slogan we got to see on billboards across the city all autumn, sponsored by Berlin’s DIY centres. To which I say: no more projects, no more DIY, get into this book instead!

Florian Illies, Berlin, 2015

BERLIN Psychogramme of a City

“The sun stood high to greet the earth,

As on the day you were born.

You got up and left: and prospered

According to the law of origin.”

Goethe

On Method

Cities are like people, no two the same.

Each one is a personality, with a specific mood, a specific aspect or character that imprints itself on the beholder. In considering this character, it makes no difference whether one was happy in a place or not, enjoyed living there or not; it is a matter of impressions that contain in nuce the whole history of the city, impressions whose objective reality transcends any feelings of sympathy or antipathy one might have. There is such a thing as a synthesizing instinct that takes what one might otherwise have termed the soul of the individual city and precipitates it as atmosphere. Every city is a record of the conditions of its founding, the factors that went into making it and making it the way it is. And this quality, persisting over hundreds of years in habits and customs, traffic and trade, architecture and costume, is continuously at work, shaping each detail, so that you see yourself confronting a singularity without being able to say what makes it so singular. It would be erring on the side of concreteness if one were to say the different atmospheres can be perceived in the way the eye distinguishes colours; nearer to the truth to say they are like different odours. Nor is it saying much to claim that cities may be aristocratic or plebeian, cheerful or gloomy, melancholy or idyllic, patrician or arriviste. Such words are as inadequate to describe a city as they are a person. It’s all in the eye of the beholder.

Nevertheless, you won’t grasp the individuality of a city until the feelings you have about it turn into thoughts, unless you make a historic analysis of the instinctive sensations in which the embryonic genesis of the city proposes itself to you, till you succeed in anchoring your instinctive response in the history a second time, consciously.

This type of analysis, this contemplation of a people’s character from the way it sets about building a city, is always tremendously instructive and pleasurable. Because if one makes the attempt to read the psychogramme of a city, one becomes aware of energies that are beyond good and bad. Wherever necessity and destiny take on visible form, you can only look on in awe. It’s not only an act of obedience to nature, it can also be a wise act to seek to identify the critical forces in places where sympathy doesn’t necessarily obtain, to take an objective view of things from which you feel yourself repelled. It is only in this way that one may be reconciled to the essential tragedy of all living beings.

Just as every human being is half typical – the product of genus and species – and half unique – the result of a particular combination of forces – so each city shows typical marks of its coming into being alongside unique signs of development specific to itself. All our historic cities went through the same process of evolution. Every one of them is the focus of greater or lesser areas of interest; everywhere the city of the merchant class, the clergy, the nobility, radiates out from the town hall, the church, the castle or court; the initial settlement becomes a fortified town, which as it grows bursts one wall after another, till finally all walls are left behind and the suburbs surge unpredictably out into the surrounding country. In every one of our old cities you can identify ring roads following the erstwhile walls and trenches, and radials heading out from the core into the countryside, and everywhere too there are clusters of the most important buildings; in a word, you see everywhere how the same social and economic needs make for a typical structure of the form of a city. But this regular, even invariable, form of becoming enacts itself differently wherever it takes place. Just as people may have numerous factors in common in the way they think and feel, while remaining physically and spiritually discrete individuals, and each human being is unprecedented and unrepeatable, so too each city is something unique.

There are cities one can only describe from the point of view of their origins, and others for which more important is what they have become. The former are almost always the true capitals, they are the focus of their respective countries or provinces, they are beautiful and prosperous, well-grown and harmonious organisms; while the others are generally places whose development was attended by difficulties, places that were forced to adjust to unfavourable circumstances and managed to prevail by sometimes artificial means. While the former resemble happy, well-balanced persons with noble and fully developed gifts, the latter are characters who have experienced the rough edges of life and, by dint of the expenditure of so much effort, have become unlovable and problematic.

Among the cities of the latter sort is Berlin. It is no individual confident of victory who subdues all comers; it is no place in which a German may feel himself at home, where he will see the most noble national traditions and the genesis of an urban history step out to greet him in a living way in the form of a solidified city culture. Rather, Berlin is a gigantic agglomeration of exigency, of need, and far harder than other cities to grasp as an entity. Nevertheless, it too is an organism and an individual, and demands to be understood as such. More than any other German city, it calls for an objective approach beyond sympathy and antipathy, as only a seemingly cool and indifferent mode of investigation is able to lift the veil of historical necessity a little. Only a look at the historical laws governing the evolution and development of Berlin, a look at the almost tragic fate of this city in all its happiness and misery, is capable of modulating one’s violent instinct of rejection to a kind of awe. Where blanket approval is impossible, and the rejection of what history has bequeathed us would be absurd, all that is left to us is the long view that takes in both the isolated object and the law of its growth, and allows us for a moment almost to set aside such terms as ugly and beautiful.

I said: almost! For who can persist for long in the point of view of a benumbed and impersonal awe!

Development as Destiny

The Colonial City

Looking for a term that applied equally to the million-strong capital city and metropolis and the original settlement of Germanic farmers and Wendish fishermen, I came upon a suggestive remark in Eduard Heyck’s book Deutsche Geschichte, where he says that the person born east of the Elbe still carries “a faint but perceptible whiff of the colonist”. Apply this happy formulation to our examination of Berlin, the capital of East Elbia, and we may arrive at the conclusion that Berlin was always the royal city in a conquered land. Even now, centuries later, it remains in some sense a colonial city.

Berlin was never a natural centre, never the predestined capital of Germany. It was always way off to the side of the principal territories of German culture, yes, of German history; in all its uncouth scale, it somehow grew off to one side. For hundreds of years, Berlin was barely mentioned when the affairs of the German Reich were discussed; this city was always extrinsic, and to some extent remains so today. Even now Berlin is a frontier city, and lies, as it has always done, on the eastern fringes of German culture. If you set off into the morning sun, no sooner have you left the gates of this frontier city than you will be in the East. The East! Which is to say: the wide, flat, immeasurable foreland of Germania, the old colonial land taken piece by piece from the more inept Slav races, the Wends and Poles, reclaimed mile after mile from a barren, inhospitable nature. The stream of German culture just about reached Berlin from its sources to the South and the West; then it dried up, as though the vast Ice Age moraines on whose sand Berlin is built had swallowed it all up. Any further East and you would be in the great beyond. The relation of the East to the South and the West of Germany is as that of a daughterland to a motherland. Berlin is an outpost, just West enough not to risk being cut off, but what comes after is steppe that seems to extend all the way into Russia: small towns, country towns, little administrative hubs. In melancholy solitude, the farm- and heathland rolls on forever; looking in any direction, the eye sees either the useful and practical, or just a hopeless desert, the forever yesterday or whatever is sufficient unto the day. Even the climate feels easterly, a little like the climate of the steppes. However long this land has been part of the Reich, it still feels newly acquired, and inhabited by a race of tough and hardy pioneers.

Don’t come to me with the names of cities that lie even further east, Dresden, Breslau, Stettin, Danzig or Königsberg. Contrary to geographical fact, Dresden doesn’t feel any further east than Magdeburg; it is on the Elbe, not in East Elbia. Breslau is orientated less towards Berlin than to the South, to Austria and to Vienna. And towns like Stettin or Danzig, yes, even to some extent Frankfurt an der Oder, belong not to the East, but the North. They are sea towns, coastal towns; they prove, if proof were necessary, that water was always better at creating connections than land, that it was the sailor not the land man who was the communicator and establisher of cultural forms. Stettin, Danzig and Königsberg, yes, even Riga and Tallinn, were as it were, fellows of Hamburg and Lübeck, foundations of the same Lower German spirit of enterprise, sites of the same Lower German culture of prosperity. Hanseatic and other trading cities are all infinitely more cosmopolitan in their freely adopted bourgeois restraint. They always felt closer to Denmark, Sweden and Holland than to any of the cities in the interior. Berlin, on the other hand, had the feeling of being far inland, landlocked in the sandy scrub and woodland of a thinly and artificially populated colony. For a long time it was not on the map, being at best a way station on the main caravan routes from the South to the North and the Northeast; a distribution point for goods destined for the East; a refuge for those who had nothing to lose. It was rare for anyone who could have stayed in the motherland freely to choose this city. The lower taxes and other privileges historically extended in Berlin are evidence of how difficult it was to keep pioneers in this German edgeland. Other towns in Brandenburg, such as Spandau or Potsdam, that came into being at roughly the same time as Berlin, and incidentally also as Wendish fishing villages, were distinguished from the city on the Spree crossing by one crucial factor. Their situations were protected – hidden, if you like – behind Berlin, in its shadow. From the outset they didn’t carry the germ of extension within them, whereas Berlin was on the open highway, where the trade routes had found a way through swamp and marsh across the Spree. For the purposes of the Middle Ages, such places as Spandau, Prenzlau, Bernau, Rathenau, Stendal, Brandenburg and others were far more typical. They all enjoyed greater significance, whether as castles and fortresses, places of refuge for the country population, bishops’ seats, residences or cultural oases, than the unprotected Berlin, a sort of chance settlement in its exposed situation. From the very start, then, Berlin had something of the shapelessness of a modern industrial city. The Berliners were involved in the same sort of struggle to survive against the depredations of the Wends as the other towns named above, but they also instinctively saw in East Brandenburg their most important market. They didn’t try to shut themselves off, they made connections reaching deep into Polish territory. And thus, through a role as intermediary between the Germans to the West and the newly German East, without ever having been conceived as a trading town, Berlin came to be a foundation not of self-defence but of enterprise. This was the basis of its modern scale and standing; it gave the town a significance beyond its actual, rather doubtful power. As is often the case, history shows us that colonies, once their raw youthful energy is seasoned, overtake the motherland; so the half-disregarded, half-contemned Berlin, effortfully developing in its distant Eastern locale, became a power, the focus of a new state, and ultimately of an Empire. In spite of which, it has remained a colonial town, always primarily dependent on the respective strength at any given time of Prussia, Silesia and Poland, always facing East and always offering each successive generation a new pioneering fantasy. It has come to be what it is because its history as a city in a certain way reflects the history of Brandenburg and of the whole Eastern colonial country. From the very beginning its raw, unstructured quality left room for limitless possibilities.