Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

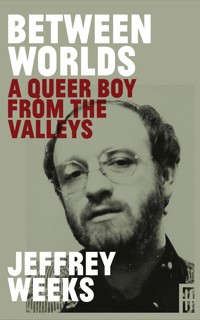

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

A man's own story from the Rhondda. Jeffrey Weeks was born in the Rhondda in 1945, of mining stock. As he grew up he increasingly felt an outsider in the intensely community-minded valleys, a feeling intensified as he became aware of his gayness. Escape came through education. He left for London, to university, and to realise his sexuality. From the early 1970s he was actively involved in the new gay liberation movement and became its pioneering historian. This was the beginning of a long career as a researcher and writer on sexuality, with widespread national and international recognition. He has been described as the 'most significant British intellectual working on sexuality to emerge from the radical sexual movements of the 1970s'. His seminal book, Coming Out, a history of LGBT movements and identities since the 19th century, has been in print for forty years. He was awarded the OBE in the Queen's Jubilee Honours in 2012 for his contribution to the social science.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 437

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Between Worlds

Parthian, Cardigan SA43 1ED

www.parthianbooks.com

First published in 2021

© Jeffrey Weeks 2021

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-1-912681-88-4

eISBN 978-1-912681-92-1

Cover design by www.theundercard.co.uk

Typeset by Syncopated Pandemonium

Printed and bound by Gomer Press Ltd, Llandysul

Published with the financial support of the Welsh Books Council.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A cataloguing record for this book is available from the British Library.

In memory of my mother and father

Eiddwen Weeks, 1921–2014

Raymond Hugh Weeks, 1924–1976

Contents

Acknowledgements

Preface

A Queer Boy from the Valleys

Beginnings

Everyday life

Being queer

London Calling

Forging an identity

The lure of the city

On the margins

Getting political

Dreams of Liberation

‘The turning point of our lives’

Doing it

High tide

Remaking personal life

Writing the Revolution

Writing as activism

Troubling identities

Gay leftism

Endings and beginnings

Making History Personal

The personal as history

Writing the history of homo/sexuality

History from below

Into sociology

Constructing controversies

Making links

Love and Loss

San Francisco: August 1981

‘Love and passion, still in fashion’

Fear and loathing

The Long March renewed?

‘Pretended family relationships’

In memoriam

Intimacy Matters

Legitimation through disaster

Love again

Getting better?

Bonding

All the Way Home

Party time

All change?

Left behind?

My tribe

Globally yours

Farewell

Memory, memories

Photographs

1. War time wedding 1944

2. Babes in arms 1948

3. With Santa, Dennis and Dad 1949

4. Student 1965

5. With Angus 1972

6. Portrait by David Hutter 1972

7. Gay Left 1977

8. On the march, with Emmanuel Cooper 1977

9. Gay News book award 1978

10. Angus as potter mid-1980s

11. Mark and Jeffrey 1992

12. Civil Partnership 2006

13. With Mam 2008

14. With Mariela Castro, Cuba 2013

15. Conferencing in Mexico, November 2015

16. Exhibition in memory of Angus, Ruthin, Wales, 2018, with Mark and Ziggy

Acknowledgements

A memoir requires a lifetime of gratitude. I’ll limit myself here to acknowledgement and warm thanks to those who have given immediate and direct help and support for me in writing this book. My first thanks are to those friends and colleagues who over the years, against my doubts, have encouraged me to write this book. I am particularly grateful to Richard Allen, Matt Cook, Richard Dyer, Mary Evans, David Horbury, Karin Lützen and Pat Macpherson for their support. They are not, of course, responsible for the end result.

I owe a special thanks to Daryl Leeworthy, who was very keen to see the book in print, and introduced me to Parthian, for which I am eternally grateful. Dai Smith, editor of the Modern Wales series, was a superb editor and encourager, reading drafts carefully and creatively, coming up with always sympathetic and empathetic proposals for improvement. My warmest thanks. Richard Davies of Parthian has been a very supportive publisher, and my thanks to him and his colleagues, especially Robert Harries, for making the production a pleasurable experience.

I am deeply grateful to all the photographers whose work is reproduced in this book. Unfortunately, passing time makes it impossible to record all their names, but I am particularly grateful to Micky Burbidge, Angus Suttie, Philip King, Philippe Rougier and Mark McNestry.

Mark lived through every stage of my writing this memoir, with patience, support and care. He read my drafts with a keen eye for typos and meanings, and the warmest understanding of what I was trying to do. He helped me to carve a coherent story from a mass of memories. I hope the final book gives some insight into what I owe to him.

Jeffrey Weeks

2 March 2020

Preface

I was born on 1 November 1945 in the Rhondda, the most famous of the South Wales mining valleys. It was a birthplace that has marked and shaped me in ways that for a long time I did not really understand or fully accept. Because of my sexuality I felt I had to escape its all-embracing intensity as soon as I could, but what my life became has always remained entwined with how my life began – as a queer boy from the Valleys.

The mythology of the Rhondda remains strong to this day, even in the marketing of Wales. A little while ago I happened to come across a copy of The Rough Guide to Wales, one of a series of well-known tourist handbooks. It opened with a list of ‘thirty-one things not to miss’ in the country. Among various tourist delights, from male voice choirs to railways, bridges to beaches, cathedrals to bog snorkelling, the number one choice is the Valleys: ‘Colourful terraces of housing, hunkered down under the hills, are the hallmark of Wales’ world-famous Valleys, the old mining areas in the south’.1 It is an image from the Rhondda that illustrates the piece.

The almost bucolic photo is of three rows of terraced houses precariously set against a vibrantly green hillside. It is a picture of the last straggling streets in Llwyncelyn, a ribbon extension of Porth, the small town at the gateway of the twin valleys. The terraces overlook at the valley bottom the old colliery complex of Lewis Merthyr, once one of the largest coal mines in the world. Its existence gave these houses meaning and justification; it is now the site of a mining museum.

The first of these three terraces is Nyth Bran, eighty or so small near-identical houses, though now nicely distinguished by different coloured doors and roofs. The uniform grey slate roof tiles of my childhood have long been replaced by red or green or duller imitation slate, markers of a new individuality that has grown hand in hand with the passing of the coal industry. Just out of sight in the picture is number 38. This was long my family home: the house where my mother’s father and mother lived and died, where my mother grew up with her sisters, got married and nurtured her husband and three children, where my father spent all his adult life and died, and finally where my mother herself passed away after living in the house for ninety-odd years. This is the house where I was born, just after the end of the Second World War.

The Rhondda then was about halfway along a trajectory that took it from the feverish growth of the mining industry before the First World War to the romanticised tourist fantasy of the twenty-first century. In 1945 it was still world renowned for its coal, carrying the greatest burden of history of all the South Wales Valleys. The string of terraced houses, small villages and townships that clung precariously to the hillsides made up a homogeneous and, although only fifteen or so miles from Cardiff, geographically self-contained culture. Despite this, it had never been totally isolated from the outside world. From before the First World War it had been at the heart of a militant socialist culture, and it had exported thousands of its young to the rest of Britain and wider, to mine, work in factories and offices, and to teach, preach, nurse, act, sing, box, play rugby or write. The mobility forced by economic depression and the Second World War had given younger people a glimpse of other ways of life, but in many ways it had strengthened the ties of home. My father’s family had left the Rhondda en masse in the 1930s for Bristol in pursuit of employment and better prospects, but my grandmother had been acutely homesick, and Dad’s immediate family had returned to Tonypandy. My mother, like two of her sisters, had also left South Wales in search of work. Two became nurses, and settled in Oxford and Croydon, while my mother ended up in Slough, working for a while in the kitchens at Eton College. This was a period of high adventure for my still-teenage mother-to-be, who looks fashionable and glamorous in the surviving photographs. However, she was called back when war broke out to be with her mother, and to work in the munitions factory in Bridgend, where she spent the rest of the war.

Many of the young men, including my father, fought all over the world in the war; others stayed put to work in the pits, which had zoomed back into full production to power the war effort after nearly twenty years of disastrous under-use in the great strikes and lockout of the 1920s, and the Great Slump, which sucked the lifeblood out of the Valleys in the 1930s. War mobilisation provided new work opportunities for women in the factories and service industries, but as normal conditions resumed after the war a more traditional division of labour reasserted itself. After demobilisation my father moved into number 38 with my mother; her mother, who was the presiding mam of the family; my mother’s sister, Aunty Lily, and later her husband, Uncle Frank; my brother Dennis, born in 1947; and me. My other brother Robert came along much later, in 1963. This overcrowded little house at the edge of Porth was home, the focus of intense domestic life until I left for university in 1964, and the heart of family life until my mother died in 2014.

That longevity in itself tells a story and marks a critical element in my own life history. I grew up deeply rooted in a particular social world and way of life. Although there were frequent rows and we often lived at the top of our voices, it was a loving and caring household. I grew up as a bright and imaginative child but was also sulky and grizzly, hypersensitive and acutely shy, blushing at everything, with a host of what my family called my habits, nervous tics and jibs, and was terrified by loud noises, especially fireworks: I managed to dodge going out every Bonfire Night, thanks to the reluctant connivance of my parents. I must have been a bit of a trial for everyone, but I can see now, and sort of took for granted then with the ruthlessness of the young, that I was deeply loved, even doted on, especially by the three forceful women at the heart of my life: my mother, Aunty Lily and their mother, Rosie – Nanny Evans (always just Nanny to me; my other grandmother was invariably ‘Nanny Weeks’) – who lived with us until she died in 1961. My relations with my father, to whom everyone said I was so similar, both physically and in personality, were more fraught and tense, with constant rows. Yet I never really doubted he was proud of me and wanted me to succeed; and I eventually recognised – too late – his own vulnerabilities, an acutely sensitive man trapped in an overwhelmingly macho identity and culture.

But there was a problem that soon became obvious to everyone, especially my father, I suspect, although it was never fully vocalised, and one that was to shape my life. In a world where boys were boys and girl were girls, by the standards of the time and place I was not quite either. I was bookish, not sporty. I preferred playing with girls rather than boys, and dolls rather than guns. When I was no longer allowed to play with dolls, I adopted a glove puppet with a sweet face and cwtched it in secret. I used my Meccano set to construct simple little houses and palaces rather than trains or pieces of machinery. I fantasised about imaginary kingdoms rather than model motor cars or football or rugby teams. I was horribly bullied by other boys and cried easily. I was slight, ginger-haired, couldn’t roll my Rs, couldn’t whistle to save my life and had a lisp. I never wanted to be a girl, but I felt a peculiar sort of little man. I was a classic sissy boy.

When my school class broke into separate teams for football or cricket the team captains used to toss a coin not to pick me. I was endlessly teased and made fun of, and on several occasions in school I was piled on between lessons by some of the class heavies and left in impotent tears and shame as the teacher came in. I didn’t come to any serious physical harm, and certainly till my mid-teens I had no sense that my increasing social and gender difference was related to being sexually different. Yet being simply a queer child, in the broadest sense, was difficult enough, and the source of constant guilt and misery. When I read much later the African-American (and gay) novelist James Baldwin’s dismissal of his childhood and schooling as ‘the usual grim nightmare’, the words stuck. I instantly identified: with his sense of exile and his minority status, his Otherness, and the deep unhappiness and isolation those produced. I know now, of course, that many thousands of little Jeffreys, as well as Jennifers, were going through similar experiences to me in hundreds of towns and villages at the same time and ever since, but the sense of being an outsider, of not fully belonging, shaped me fundamentally.

The Rhondda I grew up in was a byword for community, for neighbourliness, for warmth and mutual support. All this was true. The downside was that it was also a conservative, defensive, inward-looking culture. It bred intense local trust and strong social bonds, but also a prickly distrust of the wider world, and an acute sensitivity to criticism, especially from insiders. I vividly remember the bitterness caused by the darkly sardonic witticisms of the novelist Gwyn Thomas, a Cymmer boy who had gone to my old school thirty-odd years before and loved the Rhondda deeply, but never uncritically, and who never seemed off the television in the 1960s. It was ironic that the Rhondda proudly presented itself to the world as a politically radical society, with a strong allegiance to trade unionism and socialism, and to social transformation, yet rarely questioned the patterns of traditional everyday life. And it did not take easily to outsiders or those who were radically different. It was, as T. Alban Davies, a long-time Nonconformist minister in the Rhondda, commented, ‘a community in which it was a heresy to think differently’ – or be out of the ordinary in any way.2 As I write this I suddenly realise that my own continuing self-consciousness, diffidence and habit of walking backwards into the limelight have deeper social and cultural roots than I consciously realised.

Anyone growing up in the 1940s and 50s in the Rhondda will remember the subtle distinctions made about people that policed nonconformity and difference, even in a culture that was overwhelmingly manual working class: the comments about rough families who lived in disreputable areas (‘What do you expect? They come from . . . ’ ); about loose girls, who went to the pub unaccompanied, or went wild at Christmas parties in local factories; about dandified young married men who ‘fancied themselves’ a bit too much, and were rumoured to betray their wives – whether with men or women was never clear. Newcomers to the street, even after thirty years or more, could be treated as outsiders. ‘Blacklegs’ in local strikes would be sent to Coventry forever, with no redemption. None of this was peculiar to the Rhondda; years later I grew to know the former mining village of Chopwell in the Durham coalfield, the home of my partner Mark’s parents, and I could instantly recognise the many commonalities: the warmth, the deep local loyalties, the conformism, the curiosity about strangers and the suspiciousness about change. But the Rhondda also had its own distinctive ethos, part of a South Wales mining history where the Valleys shared a common experience of labour and struggle with other parts of the UK, yet managed to produce significantly different ways of being.

The Valleys not only had an iconic social, economic, cultural and political history, which came to define what Daryl Leeworthy calls ‘Labour country’, the heartland of radical social democracy that was not just about politics but demarcated a way of life. 3They also had a distinctive sexual and family history, which was to shape me and my generation indelibly, even as we were swept up in wider historical shifts and moved into a wider world. The dust of that past is ingrained in my body and mind like the coal residues that veined my grandfathers’ hands.

I left the Rhondda just before my nineteenth birthday, and despite regular visits in the fifty-odd years since never lived there again. I moved into different worlds, became a different person, not despite but in large part because of the love and support provided by my parents, and through the opportunities that as a bright grammar school boy in the post-1944 Education Act world the social democracy of the Rhondda offered me. Yet as a queer boy from the Rhondda I had to flee its intense embrace in order to become myself. What that self was or could be I have spent a lifetime exploring. However much it felt like it at the time, it has not been a unique or singular journey. This book is a record – inevitably partial and fragmentary – of a personal journey but also of a social and cultural transformation that has remade the world I was born into and propelled me into different worlds.

When my close friend and former partner, Angus Suttie, died in 1993 of AIDS-related illnesses a friend wrote a note of condolence containing the thought that we are ‘caught between worlds and ways of being . . . ’. It resonated with me then and continues to echo now, because it put into words a sense of living in multiple worlds that coexisted side by side but could rarely find the words to talk easily to one another. The AIDS crisis was one of a number of critical moments in my life that have dramatised both the resilience and impossibilities of traditions that were crumbling, and the potentiality but fragility of new forms of living and loving that had yet to find full validation. This book is an attempt to make sense of the different worlds, ostensibly irreconcilable but actually deeply imbricated, that I have lived in and between, and which have made me what I am today.

But let me begin at the beginning.

1 Mike Parker and Paul Whitfield, The Rough Guide to Wales, London: Rough Guides, May 2003, p. xxi.

2 T. A. Davies, ‘Impressions of Life in the Rhondda Valley’, in K. S. Hopkins (ed.), Rhondda Past and Present, Ferndale: Rhondda Borough Council, 1980, p. 11. I draw here on an earlier discussion of my life in the Rhondda in Jeffrey Weeks, The World We Have Won: The Remaking of Erotic and Intimate Life, Abingdon: Routledge, 2007, pp. 23–33.

3 Daryl Leeworthy, Labour Country: Political Radicalism and Social Democracy in South Wales 1831–1985, Cardigan: Parthian, 2018.

Chapter 1

A Queer Boy from the Valleys

Beginnings

I was the product of a wartime marriage, hastily arranged by my nineteen-year-old father over Easter in early April 1944, on his last weekend of leave before D-Day, the beginning of what my mother into extreme old age still called the ‘second front’. Ray (always Raymond to his parents, Ray to my mother and his new family) was a stoker and petty officer on a minesweeper in the home seas, and present at the Normandy landings. He had joined up as soon as he could, apparently falsifying his age, so was already a young veteran when he got married. My mother Eiddwen, nearly three years older, lived with her mother and worked in the munitions factory in Bridgend. Both Mam and Dad were children of mining families, deeply rooted in the Rhondda.

The Rhondda of the 1940s was still recognisably a product of its formative experiences at the end of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century as the twin valleys (Rhondda Fach and Rhondda Fawr, the little valley and the big valley) became for a while the most important coal-mining area in the world, a vast ‘black Klondyke’, the vibrant heart of a South Wales that had become a ‘metropolitan hub’ of Empire, with the Atlantic as its lake.4 It had seen explosive growth with the population increasing by over a third between 1901 and 1911, three times the UK average, and had some of the ethos and spirit of a frontier town, with a vibrant and raucous cultural and political life, and pubs vying for space with chapels. By 1913, the high peak of the Rhondda’s glory days, there were 53 large collieries in the two winding valleys. Coal poured down the Rhondda and Taff valleys to the ports of Cardiff and Barry, making a few people immensely wealthy, and for a while drawing thousands of men and women from all over the British Isles and beyond who were never destined to be rich but could build here a viable life. Rapid growth of population and of the higgledy-piggledy terraces, overcrowding and the unpredictable rhythms of the trade-cycle fuelled acute political and social tensions, most famously epitomised by the Tonypandy riots of 1910–11, when the Home Secretary, Winston Churchill, notoriously ‘sent in the troops’ to quell the disturbances among the miners and was never forgiven. As a young boy in the early 1950s I vividly remember cinemas audiences still erupting in loud boos whenever Churchill, by then in his second term as prime minister, appeared in a newsreel. The period before the First World War was a period of passionate political radicalisation in the Rhondda. TheMiners’ Next Step, a pamphlet that grew out of the strike that had led to the riots, explored the possibilities of syndicalism and workers’ control as a direct challenge to the long history of Lib-Labism, the deeply embedded collaboration between the Liberal Party and the forces of Labour that the long-standing local MP William Abraham – ‘Mabon’ – personified. The Tonypandy riots, a ‘carnival of disorder’ in Dai Smith’s words, had crystallised a sense of identity and community that was to shape Rhondda life for the next half-century.

By 1913, on the eve of war, the community was stabilising, and with it its values and family patterns. The real story of the Rhondda, wrote E. D. Lewis, is ‘how large masses of people from all parts of Wales and England were adventitiously thrown together to achieve, in spite of all kinds of difficulties, a quality of personal living which was probably unsurpassed among the ordinary folk of that time’.5

The journeys of my mother and father’s families to this vibrant if precarious world had been varied, each in their own way illuminating a bigger social drama. By 1911, when the Rhondda bubbled with industrial and political energy and conflict, my mother’s mother, my future nanny, Rosie, born in 1885, was living in Glyn Street, Cymmer, overlooking Porth. In the 1911 census she is named as housekeeper to her parents, David Rees, then just 60, and Elizabeth Mary Rees, ten years younger. The house, with seven rooms, was a step up from the modest terraced houses recently built all around, a mark of David’s status as a colliery foreman and later undermanager. Family history has not recorded his role in the strikes and riots of 1910–11, but it is unlikely to have been a militant one. Certainly, unlike my contemporary Dai Smith, I have no memory of heroic stories binding me to the militant past. David and Elizabeth Rees were respectable, middling people, more chapel than pub or miners’ lodge. Both had farming backgrounds: David came from a small farm of 14 acres between nearby Pontypridd and Llantrisant, and was proudly a ‘freeman of Llantrisant Common’ – an honour to which I am apparently now entitled by descent but have never had any inclination to claim – while Elizabeth’s parents had a farm in Glynfach, just above where David and she now lived. There was no absolute divide, however, between farming and mining. Family members had worked in the pits in the Rhondda as early as the 1840s, and the men of the family are variously listed as quarrymen, hauliers and labourers. The farms were too small, the families too large and the market too fragile to make farming on its own a viable career. Coal mining, a highly dangerous industry beset by pit explosions and disasters, was nevertheless a lifeline to a better existence.

The outward respectability of the Rees household hid a family secret with long-term consequences for Rosie. Also living in the house in 1911 was a two-year-old child, Olwen, listed as the daughter of David and Elizabeth. In reality she was the illegitimate daughter of Rosie – the offspring, according to my mother, of a relationship with a local married policeman. Illegitimacy at that time, and for long afterwards, could hardly have been more shameful for the woman who bore the child, and scarcely less shaming for the child. A rigid moral code particularly framed women’s sexual lives, in large part a community response to the accusations of female immorality that had marked the publication of the infamous Blue Book on education in Wales in the 1840s. Guarding the reputation of women was a prime collective commitment. This did not prevent a lively premarital sex life among young men and women, at least as suggested by the high incidence of prenuptial pregnancies, but community pressures usually enforced marriage. When that failed other subterfuges were necessary. Rosie’s parents informally adopted their granddaughter and brought her up as their own, though in these early years her actual birth mother was at hand as ‘the housekeeper’ to care for her. Like so many family secrets this was one that everyone in the neighbourhood probably knew about, but no-one spoke about. However, while growing up I developed an acute ear for these sexual misdemeanours and complexities. As an inquisitive teenager, I found out about Nanny when the minister at Rosie’s funeral spoke of her four daughters – I only knew of three. Looking around the room it dawned on me that Aunty Olwen was the fourth, which Dad later confirmed. Olwen’s own daughter remained officially ignorant of this even in her eighties. No-one, least of all her mother, had ever spoken of it to her.

This family embarrassment and shame inevitably pushed my grandmother down the minutely calibrated social ladder, only partially redeemed when she married my grandfather William in 1916, already pregnant by him with her second daughter. She had known William, eldest son of a farmer from Llanfair Clydogau, just outside Lampeter in west Wales, for some time: in 1911 he was a lodger in Rosie’s grandparents’ farm in Glynfach, employed as a shepherd. Like many of his generation, William had moved east to escape the agricultural slump but continued to utilise his rural skills: he subsequently worked as an ostler, looking after the pit ponies, in what became Lewis Merthyr colliery. My mother, born in 1921, was the youngest daughter of Rosie and William, and her father’s favourite. By all accounts he was a gentle, bookish, self-educated man, deeply religious and a lay preacher. On my mother’s death I uncovered a mass of his books, many of which I had read as a child, in an upstairs cupboard: the classic anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin jumbled with Milton’s Paradise Lost and Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, an illustrated book on Venice, Bible commentaries, and copies of the Bible itself in English and Welsh. He died of ‘dust’ – pneumoconiosis – in 1930, when my mother was 9. In her last years she would still mourn his loss.

My father’s parents had a more hazardous pathway to the Rhondda. The family of my grandfather, Uriah Weeks (always known as Hughie), came from the Monmouthshire valleys, near Pontypool in the old Abergavenny Hundred. There were strong earlier links into England via both Gloucestershire and Somerset. Hughie’s paternal grandfather, also Uriah, and his wife Mary lived on the edge of the law, a long way from respectability: in 1861 they were charged with others for forging half-crown coins, and sentenced to prison for three years and nine months respectively. He was further cautioned in 1867 for selling rotten herrings in Pontypool market, and a year later was imprisoned for another year’s custody. He seems to have had severe mental health problems, and by the 1881 census was a patient in the local lunatic asylum, where he died. The messiness of his and his wife’s lives had a direct impact on their nine children. My great-grandfather John Weeks, Hughie’s father, was listed as a two-year-old pauper in the 1861 census, when his parents were in gaol, and seems to have been in and out of the Pontypool workhouse for the rest of his youth. He was obviously a survivor, however, and eventually became a miner in the Rhondda. John and his wife Rebecca had thirteen children, eight of whom died very young. Their third child, my grandfather Hughie, was born in 1891 in Talywain, a rural coal-mining village just north of Pontypool, and by 1911 was living in Llwynypia in the Rhondda with his family, listed as a coal trimmer, and close to the epicentre of the disturbances.

The journey of my father’s mother, Meg, born in 1898, to the Rhondda is less clear-cut than either her husband’s erratic path or the upper working-class respectability of my mother’s side. She gives three different surnames in various documents, and this is explained by the complexity of the immediate circumstances of her upbringing. She was informally adopted, but her birth mother, Gwen, returned intermittently into her life and still lived locally. Her birth father also lived nearby, at one time on the same street as her mother, but seems to have played no part in Meg’s life. Meg’s mother outlived her, living a mile or so from Meg’s last home. Despite this constant proximity, I have absolutely no memory of having met Gwen. Meg married Hughie in 1921. Raymond, born in 1924, was the second of three sons, with a daughter following on much later.

A striking feature of these family journeys is that while they were epic in many ways, none of them were long distance. They represent a shaking up and ingathering of the population of South Wales and the English borders. My father’s side was the more ‘English’ one, with little Welsh-speaking tradition, and a surname most common in various forms (Wicks, Weakes, Weekes) in the English borders of Wales. All sides of my mother’s family, on the other hand, were solidly rooted in south or west Wales, and were Welsh speaking or bilingual. My DNA profile indicates overwhelmingly ‘British Isles’ origins, though there was a small admixture of north European ancestry, a very common pattern, suggesting a deeply mixed original make-up stabilised by centuries of relative population continuity. The only hint of more ancient exotica is a suggestion in my mother’s mitochondrial DNA of ancient Middle Eastern and Romany ancestry.

At my first formal dinner when I went to university, I sat next to Professor Joel Hurstfield, the leading expert of Queen Elizabeth I at the time. Hearing my still-thick Welsh accent and peering at my ginger hair and pale skin, he said, ‘second wave of Celts, just like Elizabeth’. Historians and geneticists are now more sceptical of whether the Celts really existed, let alone two waves of them, but there was undoubtedly striking evidence on all sides of long association with Wales and its peripheries, and with the fair-headed part of its ancestry. From every quarter, there was reddish/gingery hair, which I inherited.

By the eve of the First World War, in the boom years, all the elements in my family had reached the Rhondda: my mother’s side settled in Porth, my father’s in the Tonypandy/Llwynypia area. But by the early 1920s, when both my parents were born, the short-lived boom that followed the war was collapsing, and the hectic bonanza years that had created the Rhondda, with its passion and militancy, ended. The 1920s saw acute industrial strife, the prolonged miners’ strike, culminating in the general strike of 1926, and the succeeding lockout that brought poverty and despair to the community.6 The Rhondda, like other primary producing areas, suffered further in the interwar depression. William’s death in 1930 left Rosie and her children in dire poverty, refused compensation (‘compo’) by the pit, and dependent on haphazard income. Rosie took in washing, and she was helped out by William’s family farm in ‘the country’, as the Lampeter area was always known. Even in the 1950s they would send us a chicken or goose through the post every Christmas, an echo of that earlier support. Rosie’s father David and his second wife Sarah, however, clearly did not approve of her and gave little material support, though they brought up Olwen as their own daughter. Further up the valley, Dad’s family, after their migration to Bristol, returned to long-term unemployment, accentuated by Hughie’s chronic chest and heart problems. Dad won a scholarship to Tonypandy Grammar School (where George Thomas, later Speaker of the House of Commons, was one of his teachers), but left early to work in a local men’s clothing shop to support the family income – and then enlisted in the navy, whose glory years of supremacy had been fuelled in large part by Rhondda’s steam coal.

Despite the renewed wartime demand for coal from 1939 and the reconstruction that followed, by 1947 the number of mines was reduced to twelve, and the story of the Rhondda for the next half-century, despite the post-war move towards ‘affluence’, was the struggle to survive as a viable community while freeing itself from the glories and burden of coal. But coal, for good or ill, made the Rhondda, and shaped its everyday life. Coal gave the place its identity, especially its sense of itself as a community and a good place to live despite its hardships. The idea of ‘community’ as a dense network of kin, neighbours, friends and local organisations had a long resonance in the Rhondda and was an essential part of its political and moral imaginary. It was fundamentally rooted in family and place, in the dusty soil of the Valleys, but it was also diasporic, uniting those who had left across distance. ‘When are you coming home?’ was a question echoing in the ears of many an exile from the Valleys down the years, especially in the 1930s as thousands left in search of work and opportunities, but also throughout my lifetime.

It was, during all the fluctuations of the economic cycle and the fantastic rise and painfully prolonged fall of an industry, a warm, vibrant, rugged, close-knit place. Community was sustained in the hard labour and mutual dependencies of the pit, the union, the club, the chapel, the neighbourhood and the home. It was an all-encompassing ideal, yet it was also intensely local. In many ways, said Ken Hopkins, a prominent South Wales educationalist and, as it happens, my former English teacher, ‘we are of a village society. The school, the club, the chapel never more than just around the next corner’.7

My parents’ marriage in 1944 epitomises for me the culture and values of the Rhondda at that time. The urgency of the marriage was shaped by the imminence of the invasion of Europe, and the very likely possibility that my father would not survive. My father arrived in Nyth Bran without warning flourishing a special marriage licence. Nothing had been planned, nothing prepared. The neighbourhood community immediately took charge. Thomas’, the general store a few doors up the street, provided the food for the wedding. Mr Thomas’ daughters helped my mother get together her trousseau. The close families on both sides, who had never properly met before the wedding (though my mother had gone out for a while with my father’s elder brother) rallied round, and the wedding picture, which I am looking at now, fading round the edges, looks serious rather than joyous, solidly respectable rather than wildly romantic – yet to my mind now that’s what it was, a commitment until death in the midst of war: at the centre, my father youthful, slight and strikingly handsome in navy uniform, standing; my mother, pretty and fashionable, seated in her pink two-piece suit.

Everyday life

The Rhondda world they married in, and I was soon born into, had a gender and sexual order that was quite distinctive from the overall British pattern. In many ways it was, according to demographic historian Simon Szreter, closer to a surprisingly different culture. The Welsh, he argues, ‘appear to have behaved more like the French, the antithesis of the English model’.8 Couples married younger than elsewhere, and had larger families, like my great-grandparents’ generation, characteristically up to eight to ten children, though with a high infant mortality rate. Miners as a group across Britain were among the last to limit family sizes, though their fertility began to decline markedly from the 1920s, and by the time I was born both South Wales and, by extension, my parents were reverting to the British norm during the twentieth century of two or three children. As family size declined marriage became ever more normative, a pattern that survived into the 1980s in the Rhondda, as marriage rates declined elsewhere but remained high there. Marriage was the gateway to adulthood, to legitimate sex and mutual support, to respectability and a solid family life. That is not to say that marriages did not break up, but ‘the family’ in all its complexity was the glue that held everyday life together.

At the heart of family life was a sharp division of labour that seemed like a law of nature: men were the breadwinners, while women looked after the home and offspring. The origins of these patterns lay in the dependence on work in the mines, seen overwhelmingly as a man’s job, and the lack of work outside the home for women. Being able to maintain your family properly was a matter of male pride. Failure to do so was deeply shameful, in effect an emasculation. In 1935 the Rhondda MP, W. H. Mainwaring, one of the militants of 1910–11, put the position in the context of protests against unemployment and the hated means’ test with stark clarity: ‘They wanted security for their homes, sustenance for their wives. If they were not prepared to strike a blow for these things then they were not fit to be called men’.9

The family wage was an ideal that shaped values and beliefs well into the post-war world, with at first few opportunities for women’s employment outside the home. My mother worked part time in Thomas’ grocery when we were young, and then for a local catering firm. Later she cleaned for the Asian family doctor who lived in the bungalow at the bottom of the street, and eventually until her retirement worked as a school dinner lady. Dad invariably and inevitably called the little she earned her ‘pin money’, though it was more important than that for family prosperity, and by the late 1960s after Dad’s breakdown her’s became the prime household income. Though she slogged away at these jobs on top of her domestic work, my mother seemed to enjoy them, as they took her out of the house and gave her new friends. They also produced the occasional treats, especially from the catering firm: delicious cream cakes or tasty pies left over from the functions she worked on. Male culture remained distinctly patriarchal and separate. Even into the 1960s it was thought a bit shocking to see a woman in a pub on her own (a ‘slag’) – my mother certainly would never have dreamt of doing so, or even of smoking in the street – and women were excluded from working men’s clubs except on special occasions when their husbands could sign them in.

These segregated patterns were common throughout the mining communities of Britain. A well-known study of the 1950s (based in Yorkshire), Coal Is Our Life, described sharply gender-divided and embittered mining communities, with men and wives leading essentially ‘secret lives’ from one another, reflecting, perhaps, a hardening of gender divisions and an embattled sense of male pride in the difficult conditions of the 1950s.10 In the cramped and gossipy ambience of the Rhondda there was little prospect of secrets being kept for too long. There is no doubt, however, that casual violence by men against each other, and especially against their womenfolk often belied the sense of mutuality and community that was supposed to be the hallmark of the local culture. The refuge movement for women was one of the first manifestations of second-wave feminism in South Wales in the 1970s, suggesting an enduring problem of domestic violence. I have a distinct memory that the portrait of a coal-mining community in Coal Is Our Life, serialised in a Sunday paper, was heavily criticised as unfair and inaccurate even at the time in South Wales, and Philip Dodd, brought up in Grimethorpe, the area of Yorkshire described in the book, has rightly argued that it turned ‘into a collective singular what were “varying forms of life”’.11 The Rhondda and other mining areas were complex societies where the relations between men and women, though highly gendered and often fractious, and frequently violent, were not always or straightforwardly power struggles. Confrontational male dominance is not the only story. Most men and women tried to please each other and work together, and love and generosity were as common as disputes. Despite my father’s quicksilver temper and sharp, defensive and often unforgiving tongue, this was certainly true in my family. Dad, short and wiry, was proud of his toughness and would tell me and my brother about the brawls he would get involved in as a young man, but he was not physically violent towards my mother or, apart from quick slaps, us boys.

Dad never questioned the dominant forms of masculinity, which he was proud to embody, though in later life I often wondered about the degree to which he really felt comfortable with his predestined role. He was in many ways a devoted family man and took seriously his responsibilities as the main source of household income. After demobilisation, and a restless spell in the immediate post-war period in which he tried various jobs, he eventually began working in a tool-making factory in Taff’s Well near Cardiff, staying there for the next twenty years, proud that he rarely missed a day from ill health (when of course he lost pay). He was heavily involved for a while in trade union activities as a shop steward but never at the expense of his family, which was central to his existence. He always gave my mother his pay on Friday night, minus his own pocket money that he would use for travel, his Player’s cigarettes, his small bets on the horses and his Friday night out at the club with the boys. Every Sunday he would take Dennis and me to visit his parents in Tonypandy and would slip his out-of-work father a few bob. Whenever there was a family crisis around his parents or their other offspring, Ray was the son they turned to for help. He was also the go-to scholar in our immediate neighbourhood, filling in forms for neighbours terrified by petty bureaucracy. He was a kind and generous man, and I loved him deeply, but we never really got on. I found his quick temper and sharp tongue difficult to accept, especially as he always seemed so critical of my peculiarities. He was much closer to Dennis than to me, especially as my brother was more practical than I was – then as always since clumsy and totally unable to do the simplest household task without a struggle and moan.

I got on much better with the women in my life, promiscuously close to Nanny and Aunty Lily as well as my mother. She was a proud parent, always keeping us well dressed and well spoken, and was indulgent to our eating foibles – perhaps too indulgent, but she also had a husband who could be very picky. For Mam, food was the music of love. She was not a particularly versatile cook but some of her specialities – corned-beef pasties and Welsh cakes baked on a griddle – have remained treats for me all my life. Mam’s routines inevitably revolved much more than Dad’s around domestic rituals, but she also strove to carve out something of an autonomous life. She would go out regularly on a Wednesday night, sometimes with an old friend from the munitions factory days, more often on her own, to one of the local cinemas, the Central or Empire in Porth. Dad would then prepare our supper, especially potato scallops, which Dennis and I loved and looked forward to, while we watched a cowboy series on television. But by ten o’clock Dad was on edge waiting for Mam to come home, having an outburst if she was a bit late, even though she had usually rushed out before the national anthem to get home quickly. For my mother cinema was the world of escape, thrills and romance, echoed in the mysteries and Mills & Boon novels she loved to read. By the early 1960s, with greater affluence, and before my youngest brother Robert was unexpectedly born in 1963, Mam and Dad would regularly go out together on a Saturday night. What they never did together was go dancing, which my mother loved (she still had a little bop on her ninetieth birthday) but Dad loathed. They had met at a local dance hall, the Rink, but once they had hooked up Dad rarely went again. Come Dancing on television on a Monday night was my mother’s surrogate during the rest of their marriage.

My parents were in many ways well matched. Their rows could be fierce and noisy, but they usually made up quickly. When I was growing up with them, I used to think my father was the dominant character, and I usually sided with my mother when they clashed. Mam had the more emollient style, and although she had a sharp temper herself, especially in defence of her clan, her instinct was always to smooth things down. She was more diffident than my father, and it must have been difficult for my mother to assert herself fully as the dominant woman in the household when my forceful grandmother was still around. Yet by the late 1960s it was my mother who proved the more resilient of my parents, growing into her predestined role as the stoic guardian of the family as my father’s health frayed.

Like every other woman of her generation in the Rhondda, my mother had to live up to the mythologised role of ‘Mam’ in the culture: ‘The quiet, strong woman selflessly working for the good of the family, holding the purse strings, holding the family together and keeping a meticulously clean and tidy home’.12 For earlier generations of women living up to that myth was a herculean task, with large families, poor domestic conditions, overcrowding and a constant battle against grime and coal dust. Things were changing for my mother’s generation, and growing affluence and new gadgets eased domestic labour, and provided greater leisure opportunities. Sexual repression and hypocrisy, which had so shaped Rosie’s life, was also easing, and there was a certain sexual frankness, even bawdiness, at home, especially at family celebrations or Christmas, as drink weakened inhibitions – though I was too shy or prissy to enjoy or participate in such exchanges.

Yet inherited traditions of what constituted a respectable home, forged in the early days of the community, lingered on. This is nicely captured by Dai Smith: ‘Dress suits for male-voice choirs, Sunday-best outfits, China-dogs on the mantle-piece over a fire-grate blackleaded daily, the front room and tea service kept, like museum pieces, for special occasions or visitors . . . This desire for respectability, for things in the local parlance, “tidy”, could exert an almost immoveable hegemony over individual behaviour and family ambition’ – especially for women.13 Change was certainly in the air by the mid-1950s, but Nanny and my mother still blackleaded the fireplace and scoured the front doorstep, and while many other things changed in the decades that followed my mother still kept a glass-fronted cabinet full of the best china, and had Nanny’s china dogs on the mantlepiece when she died in 2014.

Like in many working-class and minority communities elsewhere, blood and neighbourliness overlapped, so that neighbours and friends were known as honorary kin, elder members called Aunty and Uncle, so that for a child it was often confusing who was blood and who was not. I was shocked as a young boy to learn at the death of our neighbour two doors down, who I knew as Aunty Crease, that she was not a blood relative, and that her sons were not my cousins. Front doors, still secured with a heavy key like the one I saw exhibited many years later for Oscar Wilde’s Reading gaol cell, were rarely locked, and neighbours were constantly popping in for a gossip or to ‘borrow’ a cup of sugar or milk.

Our house was, if warm and all-embracing, small, often uncomfortable and overcrowded, certainly in my early years, with my parents, Nanny and us boys taking up the three small (and unheated) bedrooms upstairs, and Aunty Lily and Uncle Frank lodging in the front room before they moved to a house of their own. Until the early 1950s we were still lit by gaslight, and we would struggle out to the back yard for the outside loo with a candle or a torch (that Dennis and I would get every year as one of our Christmas stocking fillers, as Dad had done in his childhood). The tin tub would be dragged into the kitchen for our weekly bath, usually on a Friday, in front of the fire. We only had a bathroom fitted, with an indoor toilet, as I went to university, built by my father – the National Coal Board that by then owned the house were not devoted to modernising their housing estate, and eventually sold them off. In my first job as a teacher in the late 1960s, I was able to take out a bank loan to help my parents, Dad by then being unable to work, to buy the house.

For most of my childhood we lived in the back kitchen. Here was the wash basin and one cold tap, the table, a couple of easy chairs huddling the open coal range, where the cooking was done, often by Nanny. An abiding memory is of Nanny cooking the Sunday dinner, the smell of roasting beef pervading the house, her face red from bending over the fire, singing a Welsh hymn as she listened to the wireless broadcast of the morning service on the Welsh programme of the BBC, with tears pouring down her cheeks from deep unspoken memories. When I hear some of this music today, wherever I am, I weep too, an unconscious homage, perhaps, to a world long gone.

From August 1953, after the Coronation, we had a small 12-inch Bush television, which was on a trolley kept in the middle room and wheeled into the kitchen once the TV service began at 7 pm. Over time, as we became more affluent, a glass-roofed extension – the ‘glass house’ – opened up the kitchen, and housed the new wash basin (with hot water), gas cooker, which took over from the range, and the fridge. Gas fires replaced the coal fires throughout the house by the mid-1960s, and we gradually colonised the middle room as the living room, while I took over the back-bedroom after Nanny’s death (and it remained ‘Jeffrey’s room’, despite my living away, till my mother’s death). The front parlour, however, remained more or less sacrosanct except at Christmas or special occasions, till my mother out of necessity made it her bedroom in the last years of her life so that she wouldn’t have to climb the stairs.

The increasing emphasis on the comforts of home into the 1960s was paralleled by a decline in what had once been the glue of family and community life. My mother and her sisters, like their friends, had been regular chapel goers in the 1930s, yet by the time Dennis and I were growing up religion played very little part in our lives. Nanny’s commitment was nostalgic and personal rather than institutionalised, and she now rarely went to the Welsh chapel in Porth. Dad’s parents, on the other hand, were for a while in my childhood deeply committed, regular attendees at Trinity chapel in Tonypandy, which had a succession of charismatic preachers. I vividly remember listening to passionate discussions about freewill and predestination over Sunday tea at their house. At various times Dennis and I were persuaded to go to Sunday school at St Luke’s church at the bottom of Nyth Bran, or the English Cong (English Congregational Church), where Mam and Dad had married, in Porth itself, but there was no real enthusiasm on either my parents’ or our part. When I got religion in my late teens it was a private and personal faith that didn’t last long.