Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

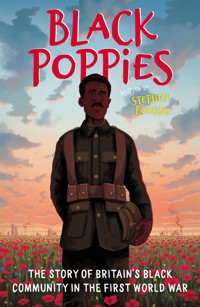

'A powerful, revelatory counterbalance to the whitewashing of British history' - Bernardine Evaristo, Booker Prize-winning author of Girl, Woman, Other In this updated edition of his acclaimed study of the black presence in Britain during the First World War, Stephen Bourne illuminates fascinating stories of black servicemen of African heritage. These accounts of the fights for their 'Mother Country' are charted from the outbreak of war in 1914 to the conflict's aftermath in 1919, when black communities up and down Great Britain were faced with anti-black 'race riots' despite their dedicated services to their country at home and abroad. With unprecedented access to the wartime personal correspondence of the Jamaican siblings Vera, Norman and Douglas Manley, Bourne helps bring to light the day-to-day trials, tribulations and tragedies of life on the battlefield. The stories of servicemen like Arthur Roberts - Scotland's Black Tommy - and Trinidadian soldier and campaigner George A. Roberts sit alongside the experiences of people of African descent at home during the First World War. These include a black police officer, munitions factory workers and even stars of the stage like Cassie Walmer. Informative and accessible, with first-hand accounts and original photographs, Black Poppies is the essential guide to the military and civilian wartime experiences of black men and women, from the trenches to the music halls.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 309

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

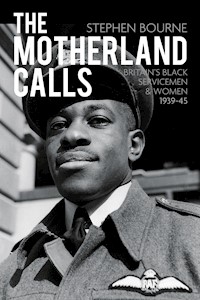

Back cover: Marcus Bailey (standing) and an unidentified soldier/

© Lilian and Adrian Bader

First published 2014

This edition published 2019

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Stephen Bourne, 2014, 2019

The right of Stephen Bourne to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7524 9787 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Author’s Note

Introduction

Black Poppies: An Extraordinary Journey

PART I: ARMY

1 All the King’s Men

2 Walter Tull

3 Lionel Turpin: A Lad in a Soldier’s Coat

4 Scotland’s Black Tommy

5 The Officer Who Refused to Lie

6 George A. Roberts and the Battle of Westminster Bridge

7 British West Indies Regiment

8 A Jamaican Lad, Shot at Dawn

9 Seaford Cemetery

10 ‘Thou Shalt Not Kill’

PART II: NAVY

11 A Sailor’s Prayer

12 Dickie Barr: Very Much a Sailor

PART III:ROYAL FLYING CORPS (ROYAL AIR FORCE)

13 William Robinson Clarke: A Wing and a Prayer

PART IV: FAMILIES

14 The James Family

15 The Easmon Family

16 The Dove Family

17 The Manley Family

18 The Manley Family Letters 1915–17

PART V: WOMEN AND CHILDREN

19 Seamstress, Domestic Service or Music Hall

20 Mabel Mercer

21 Amanda and Avril

22 Children

PART VI: THE 1919 RACE RIOTS

23 Ernest Marke: ‘We were just a scapegoat’

24 London’s East End

25 Butetown, Cardiff

26 Liverpool and the Murder of Charles Wotten

27 Black Britain, 1919

28 Legacy

Further Reading

About the Author

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Black Cultural Archives (www.blackculturalarchives.org)

British Library (www.bl.uk)

Commonwealth War Graves Commission (www.cwgc.org)

Imperial War Museum (London) (www.iwm.org.uk)

National Archives (www.nationalarchives.gov.uk)

West Indian Ex-Services Association

Peter Devitt, Assistant Curator, RAF Museum, London

Kevin Goggin

Nick Goodall

David Hankin (www.davidhankin.com)

Keith Howes

Linda Hull

Nathan Rusden

Dr Richard Smith, Goldsmiths University of London

I would like to thank two historians, Ray Costello and Jeffrey Green (www.jeffreygreen.co.uk), for their outstanding work which has been an inspiration to me. They are acknowledged throughout this book. I would also like to thank them for their support, generosity, encouragement and friendship.

Thanks to Lindsay Siviter for drawing my attention to the photograph of the black Metropolitan police officer.

Thanks to David Ball and the Manley family for permission to include extracts from some of the First World War correspondence of Norman, Roy and Vera Manley.

Thanks to Mrs Anita Bowes and the Cozier family for permission to reproduce their copy of the photo of Pastor Kamal Chunchie and the Coloured Men’s Institute outing to Reigate (1926). Pastor Chunchie’s copy of this photo can be found in the archive of Eastside Community Heritage, The Old Town Hall, Stratford, London E15 4BQ, courtesy of his family.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

In spite of its title, Black Poppies is not intended to be a book specifically about black servicemen in the First World War. The book highlights the experiences of some black servicemen and the wider black community in Britain from 1914 to 1919, both in the text and through the photographs.

Black Poppies should not be read in isolation. Since Peter Fryer’s landmark book Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain was published in 1984, several important books have surfaced that include vital information about the lives of black servicemen and Britain’s black community during and just after the First World War. Some of these are now out of print, but I would suggest that readers access them through inter-library loans, the British Library, eBay or a second-hand book dealer such as www.abebooks.co.uk. I would highly recommend the following: Under the Imperial Carpet: Essays in Black History 1780–1950 (1986), edited by Rainer Lotz and Ian Pegg, which includes chapters about black soldiers in the army in the First World War (by David Killingray) and the 1919 riots (by Jacqueline Jenkinson); Jeffrey Green’s Black Edwardians: Black People in Britain 1901–1914 (1998) for its detailed survey of the black presence in Britain in the period leading up to the outbreak of the First World War; Ray Costello’s Black Liverpool: The Early History of Britain’s Oldest Black Community 1730–1918 (2001) and Black Tommies: British Soldiers of African Descent in the First World War (2015); Glenford Howe’s Race, War and Nationalism: A Social History of West Indians in the First World War (2002) for its analysis of the impact of the First World War on the people of the Caribbean; Morag Miller, Ray Laycock, John Sadler and Rosie Serdiville’s As Good As Any Man: Scotland’s Black Tommy (2014); David Olusoga’s The World’s War (2014) and Black and British: A Forgotten History (2016); and Richard Smith’s Jamaican Volunteers in the First World War: Race, Masculinity and the Development of National Consciousness (2004) for its analysis of the impact of the First World War on Jamaican recruits into the British Army and the British West Indies Regiment. I would also like to draw the reader’s attention to Nairobi Thompson’s poetry collection Bayonets, Mangoes and Beads: African Diasporic Voices of WWI and WWII (2016) and her collaboration with Jak Beula as editors on Remembered In Memoriam: An Anthology of African and Caribbean Experiences WWI and WWII (2017). More information about these books and other relevant texts can be found in the Further Reading list at the end of this book.

I have always tried to include first-hand testimonies in my black British history books. However, for Black Poppies, first-hand accounts have been almost impossible to find because so few black servicemen from the First World War have been interviewed. I am indebted to the makers of the outstanding documentary film Mutiny (1999), written and researched by Tony T. and Rebecca Goldstone at Sweet Patootee. This was shown on Channel 4. The interviews with the handful of surviving soldiers who served with the British West Indies Regiment include the Guyanese Gershom Browne (aged 101) and the Jamaican Eugent Clarke (aged 106). They vividly recalled their lives in the trenches on the front line.

First-hand testimony is also present in Ernest Marke’s autobiography Old Man Trouble (1975), in which he presented a dramatic insight into his experiences as a young merchant seaman in the First World War. Norman Manley’s short autobiography, published in Jamaica Journal (1973), in which he reflects in detail on his war service, has also been extremely useful, but it is heartbreaking that so few first-hand testimonies of black servicemen in the First World War have been recorded and preserved.

The same is also true of the black community in Britain during the First World War, though two landmark television programmes, The Black Man in Britain 1550–1950 (BBC2, 1974) and Colin Prescod’s Tiger Bay is My Home (Channel 4, 1983), have proved invaluable for their inclusion of first-hand accounts of the 1919 race riots in Cardiff.

THE NEW EDITION OF BLACK POPPIES

In this updated edition of Black Poppies, the reader will find the stories of servicemen which were not available to me for the first edition. These have been collected over the four-year period of the First World War centenary. They include Arthur Roberts, known as ‘Scotland’s Black Tommy’, who fought on the battlefields of the Great War in the King’s Own Scottish Borderers; Lieutenant David Clemetson, the Jamaica-born officer who could have passed for white but refused to lie about his race; Sergeant George A. Roberts, a Trinidadian in the Middlesex Regiment, who fought in the battles of the Somme and Loos and the Dardanelles campaign, and whose post-war campaign led to better treatment of ex-servicemen; and the Cornish sailor Dickie Barr. The music hall career of London-born Cassie Walmer and the childhood memories of Olive Campbell, a black child raised by a white family in Wigan, have also been added.

I have been given access to personal correspondence written during the war by the siblings Vera, Norman and Douglas (Roy) Manley. These bring to light the day-to-day trials, tribulations and tragedies of life on the battlefields, as well as Vera Manley’s eyewitness account of the 1917 Russian Revolution.

Black Poppies retains chapters about the impact of the anti-black ‘race riots’ of 1919 on three communities: London’s East End, Butetown in Cardiff and Liverpool, and concludes with a revised assessment of Britain’s black community in 1919.

In addition to featuring photographs from my own private collection, I have also searched a number of photo archives for previously unpublished and unseen images of black servicemen and Britain’s black community from 1914 to 1919 for this new edition. New additions include Lieutenant David Clemetson, Private Frank Dove, music hall star Cassie Walmer, Charles Wotten (the victim of the 1919 ‘race riots’ in Liverpool), poet Claude McKay, a black Metropolitan police officer, a Bradford munitions factory worker and the Nubian Jak Community Trust’s African Caribbean Memorial to servicemen and women from the two world wars.

In Black Poppies, the terms ‘black’ and ‘African Caribbean’ refer to Caribbean and British people of African origin. Other terms, such as ‘West Indian’, ‘negro’ and ‘coloured’, are used in their historical contexts, usually before the 1960s and 1970s, which were the decades in which the term ‘black’ came into acceptable use.

Though every care has been taken, if, through inadvertence or failure to trace the present owners, I have included any copyright material without acknowledgement or permission, I offer my apologies to all concerned and will add in the correct credit in the next reprint.

INTRODUCTION

Growing up in a culturally diverse part of London in the 1960s, I absorbed a lot of what was going on around me. I come from a working-class family and was raised on a housing estate on Peckham Road. From 1962 to 1969 I was a pupil in a racially mixed primary school in Peckham. My school included a new generation of children from African and Caribbean backgrounds: their parents had come to Britain as part of the large-scale post-Second World War migration of Commonwealth citizens. When I was a youngster, what British children of all cultural backgrounds were not made aware of – in schools, in history books, by the media and only very rarely in films and on television – was that there had been a black presence in Britain since at least the mid-sixteenth century. Black historical figures from the past had been made invisible. Perhaps if this situation had been different, Britain’s first large-scale generation of black children might have felt better equipped to deal with racism. Perhaps white children, and their parents, might have been less disposed towards racism if they had been adequately informed about the longstanding black presence within Britain’s national story. The invisibility of, and silence around, Britain’s black history (or, on a more personal level, black British histories) is, of course, a problem that permeates British society and culture to this day. I have lost count of the times I have read books about the two world wars and discovered that Britain’s black and Asian citizens and other colonial subjects have been excluded.

Regarding my own awareness, I consider myself lucky. As a white child growing up in Britain, I had in my family an adopted aunt who had been born black and British long before the arrival of the ship the Empire Windrush at Tilbury docks on 22 June 1948. This marked the beginning of post-war settlement in Britain of people from Africa, Guyana and the Caribbean. Windrush carried the first wave of settlers who were seeking a new life in the land they called the ‘Mother Country’. Unlike my contemporaries, my relationship to Aunt Esther (see Chapter 22), who had been born in London in 1912, just before the outbreak of the First World War, gave me, from an early age, an awareness of the pre-1948 black presence in Britain.

I did not view the post-war settlers as a ‘threat’, or agree with those who began suggesting that ‘immigrants’ be repatriated. I was an impressionable 10-year-old on 20 April 1968 when the Conservative MP Enoch Powell made his inflammatory and objectionable ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech on immigration from the Commonwealth. He said, ‘we must be mad, literally mad, as a nation to be permitting the annual flow of 50,000 dependants … It is like watching a nation busily engaged in heaping up its own funeral pyre.’ At the same time, in British homes up and down the country, his fictional disciple, Alf Garnett, shouted racist abuse in the BBC’s situation comedy series Till Death Us Do Part. So it did not surprise me that, as a teenager in the 1970s, I witnessed a rise in popularity of the National Front, a far-right, whites-only political party. I will never forget the horror of watching – from my bedroom window – National Front supporters marching along Peckham Road with a police escort. It was like watching a Nazi rally in Germany in the 1930s. Clearly, growing up in a racially mixed community, and having an adopted aunt who was black and British, gave me insights that most white children in Britain did not get.

In 1974 I watched a fascinating television series on BBC2 called The Black Man in Britain 1550–1950. This was one of the first programmes on British television to document the history of black people in Britain over 400 years. From this series I learned about many black historical figures from Britain’s past, including the Africans Ignatius Sancho (1729–80), a writer, and Olaudah Equiano (1745?–97), an abolitionist. However, the episode that had the most impact on me was the one that featured interviews with elders from the black communities in Cardiff and Liverpool. These included Joe Friday (see Chapter 25), who recalled the terrifying anti-black race riots which occurred in a number of British seaports in 1919 in the aftermath of the First World War.

The near-total exclusion from our history books of black servicemen in the First World War is shameful. One of the few exceptions has been Walter Tull (1888–1918). In recent years he has become the most celebrated black British soldier of the First World War (see Chapter 2). Books and television documentaries have ensured Tull his place in British history, but he did not exist in isolation. I knew there were many others who had been overlooked in the history books and had to be acknowledged. Black Poppies highlights some of those men. In addition to the servicemen, Black Poppies highlights the lives of some of the black and mixed-race population of Britain who were living in the country from 1914 to 1919. They were not necessarily involved in war work, but the book will attempt to give a ‘snapshot’ of the lives of Britain’s diverse black community at that time.

Regarding the role of black women serving the British during the First World War, very little information is available. As explained in Chapter 19, women of African descent from all social classes in Britain had very few employment options. The Liverpool historian Ray Costello has shared some information about one of his aunts who was a seamstress and who made caps and uniforms in Liverpool’s Lybro Factory during the war. He explained that the factory was owned by Quakers and was one of the few that would employ black women in Liverpool (see Chapter 14). Then there is the happy, smiling face of a young mixed-race munitions worker in a Bradford factory in 1917. It is the only photograph I have found of a woman of African heritage in a First World War factory in Britain. There were probably many more of them across the country who were not photographed, but evidence is almost non-existent. More research needs to be undertaken to find out if any other black or mixed-race women were employed in Britain’s war factories. As far as the nursing profession is concerned, there appears to have been a ‘colour bar’ until the Second World War. In the 1930s, Dr Harold Moody and his League of Coloured Peoples (see Chapter 27) campaigned for British hospitals to lift this barrier, and to train and employ black nurses, but so far, with only one exception (see photo on page 128), no evidence has come to light that there were black or mixed-race women within the ranks of the British military nursing services, or the British Red Cross VADs (Voluntary Aid Detachments). There may have been a few Anglo-Indian women somewhere, but assuming that these would have had British fathers and Indian or Anglo-Indian mothers, it has not been possible to identify them.

Some black servicemen made the ultimate sacrifice in the First World War and, like Walter Tull, they died on the battlefields; but, with the passage of time, with the exception of Tull, the contributions of black servicemen have been forgotten. It is hoped that Black Poppies will help to change that.

In the first edition of Black Poppies, Nicholas Bailey made the following statement. Nicholas is an actor who, in 2008, presented the television documentary Walter Tull: Forgotten Hero for BBC4. His words are still relevant:

Make a copy of Black Poppies available to every user that can appreciate it; then ask them to go home, read it, share its stories and ask their grandparents if there is anything missing! This book is part of a conversation that we have to have and keep going. The information we’ve lost through mortality will never be known but I’m convinced that more stories lie hidden in lofts and in the recollections of those who carry vocal accounts in their memories. We need a public archive, debates, social media, lectures, plays, films, anything that helps young people want to take this history forward and own it for themselves. The conversation needs to be spread beyond academic journals and the occasional late-night documentary. The African Caribbean story of the First World War belongs in the mainstream where it can discuss it, share it, add to it and take possession of it.

BLACK POPPIES: AN EXTRAORDINARY JOURNEY

The History Press published Black Poppies on 4 August 2014, the centenary of the start of the First World War. Since my first book was published in 1991, Black Poppies has been the most successful I have written. It has taken me on an extraordinary journey that I wouldn’t have missed for anything. The personal feedback I have had from attendees at my Black Poppies talks has been both positive and emotionally charged. Black Poppies has touched a nerve, especially in the black community over the four-year centenary period. They felt excluded from the 2014–18 commemorations of the Great War, and this is hardly surprising considering the absence of black servicemen in the many First World War dramas and documentaries that have been aired on British television and radio since 2014. There have been very few exceptions.

Here are some titles that I discovered and watched. On television an episode of BBC1’s First World War drama series The Crimson Field (13 April 2014) briefly included a West Indian soldier who died from his injuries at a Red Cross hospital. David Olusoga’s acclaimed two-part television documentary series The World’s War: Forgotten Soldiers of Empire was shown on BBC2 (6 & 13 August 2014). ITV included Arthur Roberts, Scotland’s ‘Black Tommy’, in an episode of their drama series The Great War: The People’s Story (31 August 2014). He was played by Nathan Stewart-Jarrett. Roberts was also the subject of BBC4’s documentary A Scottish Soldier: A Lost Diary of WW1 (12 November 2018), movingly presented by the Scottish poet Jackie Kay. On BBC Radio 2, Sir Trevor McDonald, in the documentary High and Mighty Men of Valour (18 October 2016), presented the story of the West Indies’ role in the Great War. Black servicemen were not included in fiction films made for the cinema, set in the trenches – for example, Journey’s End (2017), directed by Saul Dibb. One of the most outstanding documentary films made for the centenary was Peter Jackson’s emotionally charged They Shall Not Grow Old (2018). Jackson and his team cleaned up grainy, crackling, silent archive footage filmed during the Great War and then added colour and a soundtrack. Jackson said: ‘I wanted to reach them through the fog of time to pull these men into the modern world, so they can regain their humanity once more.’ There is a glimpse of black soldiers, probably from the British West Indies Regiment, stacking shells on the front line. It is brief, but the footage exists and Jackson included it. It is shameful that I cannot find any other examples and, looking back over the Great War centenary, I cannot help but ask the following questions: if Black Poppies had been given a profile in the media, could something have filtered into the consciousness of programme and film makers? If this had happened, would we have seen more representations of black servicemen in dramas and documentaries?

It saddens me that Black Poppies was overlooked by the BBC. In 2014 I had a conversation about the book with Adrian van Klaveren, when he was the Controller of the Great War Centenary at the BBC. He said that he would spread the word about the book to staff at the BBC who were involved in making television and radio programmes for the centenary, but I never heard from any of them. Regarding the mainstream media, only one review appeared in a broadsheet.

On a positive note, Black History Month in October 2014 provided a space for me to promote the book at a number of high-profile venues in London, including the Imperial War Museum, City Hall, Southwark Cathedral, London South Bank University, National Portrait Gallery and BFI Southbank. As a guest speaker outside London, I attended my very first literature festival in Havant, visited the magnificent new library in Birmingham, and several universities, including Birmingham, Brighton and Hertfordshire. I also made myself available for grass roots community-based events close to my home and these included libraries (Peckham, Canada Water), Lambeth Archives and a fund-raiser for King’s College Hospital. I also visited several primary schools in Peckham and a black youth organisation called Southside Young Leaders’ Academy.

Each time I gave the Black Poppies talk I became more and more confident about putting my personal views across, based on what I had read and documented. I always stated that, unlike the United States, we did not outlaw mixed marriages or segregate black and white servicemen. Racist attitudes existed; after all, this was the time of the British Empire and black people across the world were living under colonial rule. It is part of the narrative that cannot and must not be avoided. However, what I discovered with my Black Poppies talks is that black people, especially the young, want to be empowered. They want to hear stories of comradeship and camaraderie between black and white servicemen, especially in the British Army on the front line in the battlefields of France and Belgium, and the strength, bravery and heroism of black servicemen such as Walter Tull. The stories are out there, and I am proud to say some of them can be found in Black Poppies. I always encourage people to look for the positive stories. It is important to acknowledge that not all white people were racists, and not all black people were victims.

With some funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund’s ‘First World War: Then and Now’ community project, I was able to put together a small exhibition of photographs and memorabilia relating to Black Poppies and tour it throughout the London Borough of Southwark. This now has a permanent home in the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton. Throughout 2015, as word continued to spread about the book, I was invited to give talks at The National Archives, Thomson Reuters, the Western Front Association, the Royal College of Nursing and the National Army Museum.

In January 2015 I was invited by an innovative theatre director to talk about Black Poppies at the Globe Theatre. He informed me that he was staging a production of William Shakespeare’s Othello set in the trenches of the First World War. This version of Othello was going to be presented to school children. He wanted the cast of the play to hear my talk. For Black History Month in 2015, the highlight was an invitation to give the talk at my former primary school, Oliver Goldsmith, on Peckham Road. That was an incredible experience. I hadn’t been inside the building since 1969, and the warm, friendly reception from the pupils who filled the school hall was overwhelming. Most of them came from African and Caribbean backgrounds. They responded positively to the talk and asked many interesting and sometimes challenging questions. Afterwards I visited a couple of the classrooms to meet some of the children in person and to look at their Black Poppies project work.

That same Black History Month, I gave a presentation about the book for the Department for Education. Afterwards I asked if I could be invited back at a later date to talk to some senior people at the department about ways of getting Black Poppies into schools and academies across the country. They agreed and I truly believed that I was about to make a breakthrough. However, at the meeting, I felt frozen out. They didn’t understand that there was a need to have Black Poppies in schools and academies during the First World War centenary. In desperation I informed them that all I wanted was for history teachers in British schools and academies to know that Black Poppies existed. It didn’t matter to me if they ignored the book. I just wanted them to know that it existed, so they could choose to read it and use it in their classes if they wanted to. As things stood in October 2015, they did not know the book existed because the newspapers they read hadn’t acknowledged it.

In 2016 my Black Poppies journey took me to Liverpool and an opportunity to talk to some students at one of their academies. The young people who attended my talk were extremely positive. One young lad told me afterwards: ‘When you started talking, I thought your book was going to be boring and you were going to be boring, but now I think your book is amazing and I think you’re amazing!’ This was followed by a talk at the National Maritime Museum, which was attended by Adrian Bader, the grandson of Marcus Bailey, the sailor who is featured on the cover of Black Poppies.

For Black History Month in 2016, I was invited to talk about Black Poppies at the Houses of Parliament as part of their series of lectures about the First World War. Invitations were sent to every member of the House of Lords and every Member of Parliament. The public were also invited and I was thrilled to see so many black people, including families, in attendance. About eighty people came. Sadly, no one from the House of Lords came, apart from Herman Ouseley who hosted the event, and only one MP, a Conservative, attended. Afterwards the Conservative MP stood up, introduced himself, and apologised to me and the audience for the absence of his fellow parliamentarians.

On 22 June 2017 the first memorial to African and Caribbean servicemen and women was unveiled in Windrush Square, Brixton, close to the home of the Black Cultural Archives. Jak Beula, CEO of the Nubian Jak Community Trust, had made this possible. When he addressed the audience at the event he said: ‘More than two million African and Caribbean military servicemen and servicewomen participated in the two world wars but they have not been recognised for their contribution. The unveiling of this memorial is to correct this historical omission and to ensure young people of African and Caribbean descent are aware of the valuable input their forefathers had in the two world wars.’ In addition to Jak Beula’s work, Selena Carty initiated the Black Poppy Rose project. Selena explained that the Black Poppy Rose ‘is a symbol created to remember all of our African/Black ancestors who contributed in many ways towards the First World War. Black is for the People. Poppy is for Remembrance. Rose is for Honour and Respect.’

In 2017 an enterprising history teacher at a north London academy found me on social media. When we spoke he explained that he was expected to teach his students about the First World War, which was part of the history curriculum, but the majority of them were of African and Caribbean heritage. They were not interested in stories of the war that only showed white soldiers. I accepted his invitation to visit the academy and talk about Black Poppies, and his students gave me a warm and receptive welcome. They responded positively to the images of black servicemen and the stories I told about them. In December 2017 I visited another academy, this time near my home in south London. Once again, the students were mostly from African and Caribbean backgrounds, but nothing prepared me for the reception I had after I started my Black Poppies talk. Holding the book up to show them the cover, I briefly explained what the book was about and then said: ‘You learn about African Americans from history, such as Dr Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks, but you learn about them at the expense of black people from British history.’ The class erupted. There was applause. They even stamped their feet. They shouted their approval. I felt as if I had been hit by a wave and I hadn’t even given the talk. Their teacher, as surprised as I was, managed to calm them down, and I began.

The year 2018 was an eventful one for Black Poppies. First I was approached by the Royal British Legion to give a presentation at their annual conference which took place in Warwick University. Then, for Black History Month, I found myself as a guest speaker at New Scotland Yard for the Metropolitan Police Black Police Association (MetBPA) and the Army BAME (Black Asian Minority Ethnic) Network conference at Tidworth Camp, a British Army military installation in Wiltshire. Over 500 servicemen and women attended the latter event, and afterwards one of the servicemen posted on Twitter: ‘Great talk, funny, engaging and challenging.’ All of these were memorable experiences, sharing the lives of the people in Black Poppies with new audiences, and receiving positive reactions. Many black people who attended my Black Poppies talks and events told me that there were two things that drew them to the book. First, the title and second, the image on the front cover of the First World War sailor (identified as Marcus Bailey) and soldier (so far unidentified).

If I had to choose one memorable moment from my Black Poppies journey, it would be the following. In August 2016 a letter was forwarded to me by The History Press. It had been sent to them by a prison inmate who had read Black Poppies and wanted to reach out to me. I was deeply moved when I read what he had to say and I now read the following extract at my Black Poppies events because this is what the book is about changing hearts and minds:

I am at present an unfortunate prisoner in Her Majesties prison HMP Thameside. The reason that I am writing to you is because I have just finished your book Black Poppies which has given me a rare insight into the lives of early black people of great courage and pride, living, working and standing strong. This has brought great pride into my life, bringing about a sense of pride, ownership and something I can’t quite put my finger on. Looking at the pictures was like seeing familiar faces observed growing up around me over the years. I was very impressed with the construction and well thought out content in this book. God bless you.

1

ALL THE KING’S MEN

From 1914, British-born black men from all over the country, not just the seaports of Cardiff and Liverpool, volunteered at recruitment centres, and they were joined by West Indians and other colonials. The latter travelled to the ‘Mother Country’ from the Caribbean and other parts of the British Empire, at their own expense, to take part in the fight against the Germans. Those who were unable to pay for their passage arrived here as stowaways. Their support was needed, and they gave it. It is true that some black soldiers in the British Army faced discrimination, but it is also true that others shared comradeship with white soldiers, especially on the front line. Photographs surface from time to time which illustrate this, including the black soldier in the centre of ‘Sergeant J.O. Hughes’ Squad, Welsh Guards, March 1916’. The black soldier is not pushed to the side, or placed at the back, or made invisible. He can be seen in the centre of the photo and his comrades are proud to have him there. Another photo, showing a group of tired and dishevelled Tommies at the front, includes a black soldier. The quartet have clearly been in battle together and they are friends, comrades, with a shared experience. As far as I am aware, neither of these black soldiers have been identified.

It is not a straightforward story. Nothing is clear cut, especially with the absence of first-hand testimony by black recruits. Historians simply didn’t consider them important, so they were overlooked. Unlike America, Britain did not segregate black soldiers. They integrated into British regiments. Promotion was difficult. The military wanted to avoid having black soldiers ruling over whites, but there were exceptions, such as Walter Tull, who did gain promotion and commanded white soldiers.

Page 471 of the Manual of Military Law (1914) stated that ‘any negro or person of colour, although an alien, may voluntarily enlist’ and when serving would be ‘deemed to be entitled to all the privileges of a natural-born British subject’. A note indicates that this passage relates to enlisted persons ‘and prohibits their promotion to commissioned rank’. According to the historian Jeffrey Green:

This shows that African descent enlisted people should not be promoted to be officers. It is not crystal clear, which explains why Walter Tull and others were commissioned. I know of no evidence that black men were not enlisted; when conscription came in 1916, all British-born males were surely in the pool. My understanding is that the distinction was drawn between officers and rankers, the former having authority over the latter. The conscription laws applied to all male citizens and the 1914 Manual of Military Law said the volunteers could enlist. The manual did not bar anyone. I suspect recruiting officers may have had different opinions but there seems to have been no law that excluded black men from being enlisted. We are being told a story backwards; without knowing how many blacks were subject to conscription in 1916–18, an assumption is made that, because officers could not be black, rankers could not be black. There are enough photographs of blacks in standard regiments to show that they were not siphoned off into ‘ethnic’ regiments such as the British West Indies Regiment. Imagine a recruiting station somewhere in Britain before conscription. A bunch of lads turn up and volunteer, and are processed. How many sergeants or officers would say that one (or more) of the group of pals could not be accepted? After conscription was legislated, anyone presenting their papers would be processed. Excluding blacks would upset the other reluctant recruits who were only there because they had to be there. Turn down one and the others would be aggrieved.1