Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

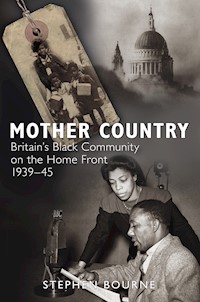

Very little attention has been given to black British and West African and Caribbean citizens who lived and worked on the 'front line' during the Second World War. Yet black people were under fire in cities like Bristol, Cardiff, Liverpool, London and Manchester, and many volunteered as civilian defence workers, such as air-raid wardens, fire-fighters, stretcher-bearers, first-aid workers and mobile canteen personnel. Many helped unite people when their communities faced devastation. Black children were evacuated and entertainers risked death when they took to the stage during air raids. Despite some evidence of racism, black people contributed to the war effort where they could. The colonies also played an important role in the war effort: support came from places as far away as Trinidad, Jamaica, Guyana and Nigeria. Mother Country tells the story of some of the forgotten Britons whose contribution to the war effort has been overlooked until now.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 296

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MOTHER COUNTRY

MOTHER COUNTRY

Britain’s Black Communityon the Home Front1939–45

STEPHEN BOURNE

This book is dedicated to Frederick Pease who was killed in an air raid during the London Blitz in February 1941. He is the unknown black civilian ‘remembered with honour’ and ‘commemorated in perpetuity’ by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. According to the Record of Civilian Death (due to war operations), now held in Kensington and Chelsea’s local studies archive, Pease was killed in a ‘bomb blast’ at the age of 60, and had ‘no relatives whatsoever’.

First published 2010

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Stephen Bourne, 2010, 2013

The right of Stephen Bourne to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9681 8

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Author’s Note

Introduction

‘Let Us Go Forward Together’

Chapter 1

Dr Harold Moody

Chapter 2

Leading and Inspiring the Community

Chapter 3

Keep Smiling Through

Chapter 4

Esther Bruce

Chapter 5

The Evacuee Experience

Chapter 6

‘Front-liners’ in Civilian Defence

Chapter 7

When Adelaide Hall Went to War

Chapter 8

Keeping the Home Fires Burning

Chapter 9

London Calling

Chapter 10

Front-line Films

Chapter 11

For the Mother Country

Postscript

If Hitler Had Invaded Britain

Endnotes

Further Reading

About the Author

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Arts Council England

Black and Asian Studies Association

BBC Written Archives Centre

British Film Institute

Cuming Museum (London)

Imperial War Museum (London)

Ian Brown

Sean Creighton

Tina Horsley

Keith Howes

Linda Hull

Professor David Killingray

Simon Mason

Marika Sherwood

Aaron Smith

Robert Taylor

The extract from Langston Hughes’ The Man Who Went to War (see Chapter 9) has been reprinted with the permission of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated (copyright 1944 by Langston Hughes).

Though every care has been taken, if, through inadvertence or failure to trace the present owners, we have included any copyright material without acknowledgement or permission, we offer our apologies to all concerned.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

In Mother Country my use of the term ‘black’ means people of African descent, usually African Americans or Africans, Caribbeans and black Britons. Terms such as ‘negro’, ‘West Indian’, ‘West Indies’ and ‘coloured’ have been used in their historical contexts, usually before the 1960s and 1970s, the decades in which the term ‘black’ came into popular use.

This book is not intended to be definitive; the reader will find some gaps. It reflects my interest in the home front, not the military, so there are only a few references to those who served in the armed forces. The experiences of African American GIs have already been extensively covered by Graham Smith in When Jim Crow Met John Bull – Black American Soldiers in World War II Britain (I.B. Tauris, 1987) and readers may want to consult the following books for a wider view of the subject: Amos A. Ford’s Telling the Truth – The Life and Times of the British Honduran Forestry Unit in Scotland (1941–44) (Karia Press, 1985); Marika Sherwood’s Many Struggles – West Indian Workers and Service Personnel in Britain (1939–45) (Karia Press, 1985); Hakim Adi and Marika Sherwood’s The 1945 Manchester Pan-African Congress Revisited (New Beacon Books, 1995) and back issues of the newsletters of the Black and Asian Studies Association, founded in 1991.

I wanted to include a chapter about Butetown in Cardiff, which has one of the oldest black communities in Britain, but through no fault of my own I was unable to access the archives of the Butetown History and Arts Centre. However, I have mentioned Butetown in my chapters about women (Chapter 3), evacuees (Chapter 5) and civilian defence (Chapter 6).

INTRODUCTION

‘LET US GO FORWARD TOGETHER’

I know too well that we would never allow it to be said of us that when the freedom of the world was at stake we stood aside.

Una Marson (Jamaican broadcaster) in Calling the West Indies,BBC radio broadcast to the West Indies, 3 September 1942

In 2007 I was moved to tears when I attended a memorial to an entire family of thirteen wiped out in the German Blitz on London in 1940. It had taken sixty-seven years for the memorial to be erected. The tragic incident occurred when an underground shelter on Camberwell Green in south-east London took a direct hit from a 500lb German bomb. When I was growing up in London in the 1960s and 1970s, my family told me many stories about life on the home front, which was the name given to the activities of a civilian population in a country at war. I was an impressionable child, and all through my early, formative years, my head was filled with dramatic, true life stories about the Second World War: air raids, evacuation, food shortages, doodlebugs and how communities pulled together and survived these terrible ordeals. I was fascinated by how the war affected my family and everyday people. Unlike other boys, I was not interested in stories about battles on land, sea and air.

The war impacted greatly on my family. In 1940 my mum was evacuated from London to her Irish Catholic grandparents in Merthyr Tydfil, South Wales. She remembered looking over the mountains towards Cardiff on the nights the city was bombed. The sky over Cardiff glowed red, so they knew something terrible was happening, and Granny Murray clutched her rosary beads and prayed.

Thunderstorms reminded my dad of air raids. In the middle of the night, when my sister and I were small children, as soon as a roll of thunder could be heard in the distance, dad would wake us up and carry us downstairs until the storm had passed. We were aware that something terrible had happened to him as a child, but we didn’t find out the truth until later. Norman Longmate, a historian of the Second World War, advertised for memories of the doodlebugs (flying bombs) for a book about the subject. Dad wanted to make a contribution to the book and in doing so he revealed to my sister and I the full horror of what had happened to him at the age of 12. In June 1944 a doodlebug exploded and flattened his house (and half his street), and he was caught in the blast. Dad and his family were buried alive. He didn’t know how long they remained in the rubble: ‘The next thing I can remember was someone picking me up and saying “alright, son. You will be alright now.” I was placed on a stretcher at the end of our turning to await the arrival of the ambulance. It was then I realised my face was wet with blood and my eyes would not open.’1

Then there was Aunt Esther (see Chapter 4), a black Londoner who became part of my family during the Blitz when my great-grandmother, known as Granny Johnson, ‘adopted’ her. In their tight-knit working-class community in Fulham, granny was a mother figure, loved and respected by everyone. When Esther’s father was killed in 1941, she was left alone. Her only relatives were in British Guiana, so granny offered her a home.

My interest in documenting the experiences of black Londoners on the home front began with the stories my Aunt Esther told me. During the war she gave up her job as a seamstress to do war work. She became a fire watcher during air raids. While recording my aunt’s memories, I began searching for other stories of black people in wartime Britain and I discovered many who have been ignored by historians in the hundreds of books and documentaries produced about Britain and the Second World War. For example, when I was still a teenager, I bought a copy of Angus Calder’s The People’s War, first published in 1969. Calder mentioned the existence of a black air-raid warden – E.I. Ekpenyon – in London: ‘One Nigerian air raid warden in an inner suburb was regarded as a lucky omen by shelterers.’ So at an early age I was made aware that Aunt Esther was not the only black person in London, or indeed Britain, during the war.2 Some recently published books about Britain and the Second World War have started to acknowledge the black British presence, but not in any depth. In London at War 1939–1945 Philip Ziegler mentions E.I. Ekpenyon, Learie Constantine and Ken ‘Snakehips’ Johnson. In Wartime Britain 1939–1945 Juliet Gardiner also mentions Constantine (though not his war work) and Johnson, and devotes several pages to the plight of the black American GIs, but she doesn’t mention Dr Harold Moody and the campaigning work he undertook with his organisation the League of Coloured Peoples. In fact, if historians have acknowledged the black presence in Britain in wartime, it is usually the experiences of black American GIs, not black Britons.

It has been estimated that there were at least 15,000 black and mixed race citizens of African, Caribbean, American and British backgrounds in England, Wales and Scotland when war was declared on 3 September 1939, but the figure could have been as high as 40,000.3 At the outbreak of war, the largest black communities were to be found in the Butetown (Tiger Bay) area of Cardiff in South Wales, Liverpool and the Canning Town and Custom House area of East London’s dockland. In 1935 Nancie Hare’s survey of London’s black population recorded the presence of 1,500 black seamen and 250–300 working-class families with West Indian or West African heads of households.4

Despite evidence of racial discrimination black people contributed to the war effort where they could. In Britain, black people were under fire with the rest of the population in places like Bristol, Cardiff, Liverpool, London and Manchester. Many volunteered as civilian defence workers, such as fire watchers, air-raid wardens, firemen, stretcher-bearers, first-aid workers and mobile canteen personnel. These were activities crucial to the home front, but their roles differed from those in the armed forces. Factory workers, foresters and some nurses were recruited from British colonies in Africa and the West Indies. Before the Second World War, many in Britain viewed the colonies there as backwaters of the British Empire, but when Britain declared war on Germany, the people of the empire immediately rallied behind the ‘mother country’ and supported the war effort. Throughout the empire black citizens demonstrated their loyalty. Many believed that Britain would give them independence in the post-war years, but they recognised that, for this to happen, a battle had to be won between the ‘free world’ and fascism. This instilled a sense of duty in many citizens of the empire. Many in the colonies made important contributions, for example, by volunteering to join the armed services, coming to Britain to work in factories, donating money to pay for planes and tanks, and knitting socks and balaclavas. This important input to the war effort has been ignored by historians. For some it may seem strange that black people would support a war alongside white people who did not treat them with equality, but the need to win the war, and avoid Nazi occupation, outweighed this.

In the course of my research, many stories came to light about black servicemen and women, and civilians, facing up to racist attitudes in wartime Britain from both the British and American men who were based there. After the USA entered the war in December 1941, in the following year, the arrival of around 150,000 African American US soldiers added to the moral panic of ‘racial mixing’. Black American GIs were segregated from white GIs, but black Britons and their colonial African and West Indian counterparts served in mixed units. It was not uncommon for non-American blacks in Britain to find themselves subjected to racist taunts and violence from visiting white American GIs. Conscious of the abuse some black Britons were being subjected to, in 1942 the Colonial Office recommended that they wear a badge to differentiate them from African Americans. Harold Macmillan MP supported the idea and suggested ‘a little Union Jack to wear in their buttonholes’. Needless to say, the idea came to nothing.5

One story that sticks in my mind is that of Jack Artis, a black British army sergeant who, before he died in 1998, told stories to younger members of his family about racist attitudes in wartime Britain. Jack particularly loathed the white American GIs. His wife Joan, whom he married in 1944, related a story that illustrates this. There was a family reunion in a local pub, a rare occasion which allowed them all to be together, including several who were serving in the armed forces (two in the army, two in the navy and one in the RAF): ‘Into the pub came some white GIs, apparently some snide remarks were not long forthcoming from the GIs, all aimed at Uncle Jack. The GIs got more than they bargained for as the people in the pub (besides our family) all knew and liked Jack. The GIs were turned upon and after a “scuffle” were unceremoniously ejected from the pub and told not to return again in no uncertain terms.’ Jack Artis added: ‘We were there to fight the Nazis, who believed in white supremacy, so God alone knows what they [the GIs] thought they were fighting for.’6

Very little information has been made available about black people and the Second World War. In books about the home front historians and television documentaries perpetuated the myth that only white people took part. In the 1990s the Imperial War Museum, with the help of consultants and experts like Marika Sherwood from the Black and Asian Studies Association, Linda Bellos, a local activist in Lambeth and the historian Ben Bousquet, began to acknowledge the existence of black servicemen and women in wartime. The museum achieved this with exhibitions, talks and ‘Together’ (1995), a multi-media resource pack aimed at schools, but information about the black presence on the home front was mostly absent. In September 2000 I tried to address this with an article about the subject in BBC History Magazine, which was later reprinted in the Black and Asian Studies Newsletter. By then I had learned a great deal about the wartime contributions of Dr Harold Moody (see Chapter 1) and Learie Constantine (see Chapter 2), published books about Aunt Esther and the singer Adelaide Hall (see Chapter 7), interviewed a black evacuee from London’s East End (see Chapter 5), read E.I. Ekpenyon’s Some Experiences of an African Air Raid Warden (1943) (see Chapter 6) and Delia Jarrett-Macauley’s acclaimed biography of the BBC producer Una Marson (see Chapter 9), began interviewing people from the former colonies in Africa and the West Indies about their experiences of the home front (see Chapter 11), and discovered what might have happened to Aunt Esther and other black people in this country if Hitler had invaded Britain in 1940 (see Postscript).

With lots of interesting material – and hope – I began to approach publishers with a proposal for this book, but I was unprepared for the rejections. On a positive note, the Imperial War Museum invited me to present a talk about the black presence on the home front during Black History Month in 2002, and they continued to do so for several years. In 2008 they invited me to join a group of consultants on their ‘War to Windrush’ exhibition.

In spite of the success of ‘War to Windrush’ and a similar exhibition that I helped to research which also looked at black participation in wartime, ‘Keep Smiling Through – Black Londoners on the Home Front 1939–1945’, at the nearby Cuming Museum, absences still exist. For example, to mark the seventieth anniversary of the outbreak of the Second World War on 3 September 2009, a week-long series of television programmes was shown on BBC1 from 7–11 September; the daytime series The Week We Went to War, presented by Katherine Jenkins and Michael Aspel, celebrated the heroes of the home front. However, black people who contributed to the war effort remained unmentioned. The Imperial War Museum’s ‘Outbreak 1939’ exhibition was more inclusive, and made room for the Nigerian air-raid warden E.I. Ekpenyon and the singer Adelaide Hall, who was prominently showcased with her white contemporaries, Gracie Fields and Vera Lynn. ‘Outbreak 1939’ sent a small flare into the night sky. I hope that Mother Country will help to light up that sky and draw attention to a subject that has been neglected for far too long. Thanks to The History Press, this has been made possible.

CHAPTER 1

DR HAROLD MOODY:

BRITAIN’S MARTIN LUTHER KING JR

Dr Harold Moody was born in Jamaica but lived in Peckham, south-east London, for most of his life, from the Edwardian era until his death in 1947. In the 1930s and 1940s Moody was more than just a popular family doctor. He was an ambassador for Britain’s black community and an important figurehead who – with his organisation the League of Coloured Peoples (LCP) –campaigned to improve the situation for black people in Britain, especially during the Second World War. In 1972 Edward Scobie described Moody in his book Black Britannia as a man whose leadership and strength of character won the respect of English people and carried the League through many difficult periods, gaining it the respect and admiration of white and black alike. Scobie adds that Dr Moody’s counterpart could be seen in the charismatic African American leader Dr Martin Luther King Jr:

They were both devout men with an innate love of mankind and the profound belief that in the end, good will prevail. To many extremists among the Africans and West Indians in Britain in the thirties, Dr Moody was looked upon as something of an Uncle Tom – much as Black Power supporters and some extremists looked upon Dr King in his last years. This in no way detracts from the good that Dr Moody and the League of Coloured Peoples did for the thousands of blacks living in Britain between the two world wars.1

Harold Moody’s Early Life

Harold Arundel Moody was born in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1882, the eldest of six children. Harold’s father Charles was a successful businessman. He owned a chemist shop, the Union Drugstore, in West Parade, Kingston, the largest town in Jamaica. Although slavery had been abolished in Jamaica in 1834, Harold’s mother Christina had been denied an education. As a young girl she entered domestic service with a white family. Nevertheless, Christina was ambitious for her six children and was a very forceful presence in their lives. She provided a loving and secure home for her family and possessed a sense of humour which was infectious. Christina wanted the best education for all her children, and managed to realise her ambition. For example, Harold’s brother Ludlow studied at King’s College Hospital in London (1913–18), where he won the Huxley Prize for physiology. He later returned to Jamaica to become the government bacteriologist. Ronald Moody, Harold’s third brother, studied dentistry at King’s College London, practised for a few years, and then became a professional sculptor.

Harold was encouraged to study hard and did well at school. As a young man he became a devout Christian and his faith was the mainspring of his life and activities. When Harold was growing up, Jamaica was part of the British Empire and Harold was raised on the belief that England was the mother country. His colour may have been a factor in his failure to secure a scholarship to further his education, but in spite of this he was determined to have a career in medicine. With his mother’s support, Harold sailed to England in 1904, at the age of 21, to study medicine at King’s College Hospital, then situated in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and now at Denmark Hill.

In those days white Britons had little exposure to life in other parts of the British Empire and had limited contact with black people. The black population of Britain may not have numbered more than 20,000 by 1914 and they were mainly concentrated in sea ports, such as Cardiff, Liverpool and London’s East End.2 The young Harold was completely unprepared for life in Edwardian London. He found it hard to find a place to live. On his arrival he had visited the Young Men’s Christian Association in Tottenham Court Road where he obtained a list of addresses where he might find accommodation. However, at every address he went to the landlord or landlady turned him away. He finally found somewhere to live in a small and dingy attic room in St Paul’s Road, Canonbury.

At this time, Harold often encountered British people whose knowledge and understanding of black culture was limited. They were surprised to meet an educated, well-spoken black man who was more British than themselves. Harold did not allow these experiences to deter him from training to become a doctor and making a new life for himself in the mother country.

Having received several academic awards, Harold qualified as a doctor in 1912, but, though he was the most qualified applicant, he was denied a position at King’s College Hospital because of open racial discrimination. He also applied for an appointment as one of the medical officers of the Camberwell Board of Guardians. A doctor who was a member of this board stated publicly that Dr Moody had the best qualifications of all the applicants, but because of racial discrimination he was not given the appointment. Of this incident Harold wrote: ‘I retreated gracefully and applied myself to the building up of my private practice.’3

Work and Family

Forced into self-employment, the new Dr Moody started his own practice in Peckham at 111 King’s Road (now King’s Grove) in February 1913. In 1922 Harold moved his family to their second Peckham home: a spacious, rambling Victorian house at 164 Queen’s Road. A deeply religious man, he felt strongly that God had called him to serve the people of south-east London. In the first week his takings amounted to just £1, but gradually they increased as the people of nearby Peckham and the Old Kent Road grew to know and trust the sympathetic doctor. His daughter Christine said: ‘He was a very popular person in Peckham because of his practice. He was a very good doctor and people appreciated this. People came from far and near to see him.’4 Dr Moody practised in Peckham in the days before Britain had a National Health Service and working-class families faced hardship when they tried to find money to pay doctors for medical treatment. Dr Moody often treated the children of working-class families for no charge.

Harold also found time for a personal life. In 1913 he married Olive Tranter, a kind, affectionate English nurse. Mixed marriages were uncommon in Edwardian England, and some couples faced hostility and discrimination, especially if they had children. Fearing for the young couple, the Moody and Tranter families tried to persuade them not to marry, but from the start of their relationship the couple were devoted to each other. Their wedding took place at Holy Trinity Church in Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire. Harold and Olive had six children, all born in Peckham: Christine, Harold, Charles, Joan, Ronald and Garth. Meanwhile, family and work commitments prevented Harold from visiting Jamaica. He returned on only three occasions, in 1912, 1919 and finally in 1946–47.

Founding the League of Coloured peoples

As well as being a doctor, Harold Moody was driven to be active in his community. As a Christian, he became involved with church affairs as soon as he arrived in Britain. By 1931 he was president of the London Christian Endeavour Federation, and he became involved in the administration and running of the Camberwell Green Congregational Church in Wren Road, where he was a deacon and lay preacher. He often used church pulpits to put across his views of racial tolerance. English dignitaries attended these services, the highlight being the singing of spirituals. Harold’s experiences of hardship and racial discrimination also led him to become the founder and president of the League of Coloured Peoples. The organisation became the first effective pressure group in Britain to work on behalf of its black citizens.

The 1920s and 1930s were a difficult period for black people in Britain, especially settlers from Africa and the Caribbean. Cities like Cardiff, Liverpool and London were often highlighted as places where hotels, restaurants and lodging houses refused to accept black people, but racial prejudice was widespread and institutionalised. Like most settlers of African descent, Harold had become frustrated with the racial discrimination he encountered in Britain. He helped many black people who came to him in distress. They told him about the difficulties they faced in trying to find work or somewhere to live. Sometimes Harold would take it upon himself to confront employers and make a powerful plea on behalf of those who were being victimised. Soon, other middle-class black people in Britain joined Harold in his crusade for equal rights, and before long they realised they would be more effective if they formed an organisation. In 1931 the League of Coloured Peoples was born.

The League had four main aims: ‘protect the social, educational, economic and political interests of its members; interest members in the welfare of coloured peoples in all parts of the world; improve relations between the races; and co-operate and affiliate with organisations sympathetic to coloured people.’ In 1937 a fifth goal was added: ‘to render such financial assistance to coloured people in distress as lies within our capacity.’5

In the 1930s the League based itself at Harold’s home in Queen’s Road, Peckham, which became a popular meeting place for black intellectuals. The visitor’s book read like a who’s who of black historical figures. Visitors included the famous singer and actor Paul Robeson; Trinidadian historian and novelist C.L.R. James; Kwame Nkrumah, who became president of Ghana; Jomo Kenyatta, who became the founding president of the Republic of Kenya; and the Trinidadian cricketer Learie Constantine (see Chapter 2).

Other black people who had made Britain their home supported Dr Moody and the League, including Dr Cecil Belfield Clarke of Barbados, George Roberts of Trinidad, Samson Morris of Grenada, Robert Adams of British Guiana and Desmond Buckle of Ghana. Also present at the League’s first meeting was Stella Thomas who would later become the first female magistrate in West Africa. Dr Moody saw the League primarily as serving a Christian purpose, not a political one. Yet for two decades the League was the most influential organisation campaigning for the civil rights of African and Caribbean people in Britain. Through various campaigns and The Keys, a quarterly journal first published in 1933, the League struck many blows against racism in Britain. It was devoted to serving the interests of African and Caribbean students, and campaigned for African and Caribbean settlers to be given better housing and greater access to employment. For thousands of black people in Britain, The Keys was the main vehicle for airing their racial grievances. In 1939 the publication of the journal was suspended due to lack of funds. During the war its place was taken by the News Letter.6

In 1941, in the League’s News Letter, Arthur Lewis said: ‘At the outbreak of this war spokesmen of the British Government made speeches denouncing the vicious racial policies of Nazi Germany and affirming that the British Empire stands for racial equality. It therefore seemed to the League … that the time had come once more to direct the Government’s attention to its own racial policy, and if possible to get these fine speeches crystallised into action.’7 The height of the League’s influence as a pressure group came in 1943 when the organisation held its twelfth annual general meeting in Liverpool. It was attended by over 500 people and one of the talks concerned ‘a charter for colonial freedom’. The following year the League drafted ‘A Charter for Coloured People’ and the text included a demand for self-government for all colonial peoples. It also declared that all racial discrimination in employment, restaurants, hotels and other public places should be made illegal and ‘the same economic, educational, legal and political rights shall be enjoyed by all persons, male and female, whatever their colour’. The charter foreshadowed the resolutions of the 1945 Pan-African Congress in Manchester. The League was the forerunner of such organisations as the Race Relations Board (1965–76) and the Commission for Racial Equality (1976–2007).

‘Joe’ Moody and Racism in the British Army

During the Second World War, five of Dr Moody’s six children received army or RAF commissions. Dr Moody’s son Ronald served in the Royal Air Force. His daughter Christine and son Harold both qualified as doctors and, after a short period in practice at Peckham, they joined the Royal Army Medical Corps and became captain and major respectively. Moody’s youngest son Garth was a pilot-cadet in the Royal Air Force. However, at the start of the war Dr Moody found himself challenging the war office when one of his sons was informed that he could not become an officer in the British army because he was not ‘of pure European descent’.

In 1939 Dr Moody’s 22-year-old son Charles Arundel, known as ‘Joe’, qualified for basic training as an officer in the British army. He went to a recruiting office in Whitehall and was interviewed by a captain. Joe recalled in the Channel 4 television documentary Lest We Forget (1990): ‘The Captain was obviously quite embarrassed with my being there.’8 After the captain talked to the major, he informed Joe that he could not become an officer because he was not, in spite of being born in England, ‘of pure European descent’. The captain then suggested that Joe join the ranks and hopefully be commissioned as an officer at a later date.

When Joe informed his father about his rejection, Dr Moody fought back. Joe said: ‘He immediately picked up the telephone and spoke to the Colonial Office and made an appointment with one of the under-secretaries. That started the wheels in motion for getting the Army Act changed which enabled members of the colonies to have commissions in the forces for the duration of the war.’9 Dr Moody led the campaign to change the law, and joined other members of the League, as well as the International African Service Bureau (IASB) and the West African Students’ Union, to lobby the government. Letters to the press and editorials in The Keys and the News Letter, reinforced by speeches in public and private lobbying by Dr Moody, all made a difference. On 19 October 1939 the Colonial Office issued the following statement: ‘British subjects from the colonies and British protected persons in this country, including those who are not of European descent, are now eligible for emergency commissions in His Majesty’s Forces.’ But Dr Moody remained unsatisfied: ‘We are thankful for this,’ he said, but ‘we do not want it only for the duration of the war. We want it for all time. If the principle is accepted now, surely it must be acceptable all the time.’10

Joe Moody was sent to Dunbar in Scotland where he joined an officer-cadet training unit for four months of intense training. Joe said: ‘I was a guinea pig, so I had to be very careful and really perform outstandingly. And I didn’t get thrown out so they must have thought I could make it.’ When he was commissioned Joe was given some advice by his company commander: ‘He took me into his office and he told me that I was going to a good regiment and that I would be the first coloured officer to walk into their officers’ mess, and there would be dead silence, but I was not to be embarrassed. And he said, “Joe, do your job and when your time comes to shine you will shine.” That was great advice.’11 In 1940 Joe became only the second black officer in the British army when he joined the Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment; the first being Walter Tull in 1917.12

Dr Moody and the League of Coloured Peoples during the War

During the Second World War, thousands of black workers and military personnel came to Britain from colonies in Africa and the Caribbean to support the war effort and this increased the workload of Dr Moody and the League, but it also gave him and the organisation greater purpose and influence. In 1940 Dr Moody forced the BBC to apologise after a radio announcer used the word ‘nigger’ during a broadcast. He complained that ‘this is one of the unfortunate relics of the days of slavery, vexatious to present day Africans and West Indians, and an evidence of incivility on the part of its user’.13 In a written statement to Dr Moody, dated 16 May 1940, the BBC admitted liability for the presenter’s comments and offered a full apology. In 1942 Dr Moody wrote a letter of protest to the director general of the BBC after the exclusion of Africans and West Indians from their radio programme Good Night to the Forces.

When the Jamaican nationalist leader Marcus Garvey died in London on 10 June 1940, Dr Moody wrote a moving tribute in the League’s News Letter. He described Garvey as one of the greatest men the League had been associated with: ‘No other man operating outside Africa has so far been able to unite our people in such large numbers for any object whatsoever.’14

At the height of the London Blitz, in addition to his work as a GP and a campaigner, Dr Moody continued to produce the League’s monthly News Letter, and in an editorial he said: ‘our work, such as the preparation of this letter, has to be carried on to the hum of hostile planes and the boom of friendly guns.’15

Dr Moody’s influence continued to grow. He accepted an invitation to visit Buckingham Palace on 12 December 1940. On this occasion Her Majesty the Queen (the present queen’s mother) received a fleet of thirty-five mobile canteens in the forecourt of Buckingham Palace. The mobile canteens had been purchased and provided by the colonies on behalf of Britain. Dr Moody’s life-long friend and biographer, David A. Vaughan, described this important occasion in Negro Victory (1950), his biography of Dr Moody: ‘During the ceremony Moody was presented to the Queen [who] made enquiries concerning the welfare of the people of his race and displayed a real interest in them.’16 The League’s News Letter said: ‘The canteens will serve hot drinks and food to people in London and other cities who have been bombed out of their homes, or who, during the winter, have to spend long and anxious nights in shelters away from their homes.’17