Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

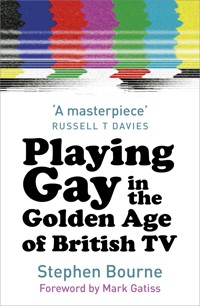

The television set – the humble box in the corner of almost every British household – has brought about some of the biggest social changes in modern times. It gives us a window into the lives of people who are different from us: different classes, different races, different sexualities. And through this window, we've learnt that, perhaps, we're not so different after all. Playing Gay in the Golden Age of British TV looks at gay male representation on and off the small screen – from the programmes that hinted at homoeroticism to Mary Whitehouse's Clean Up TV campaign, and The Naked Civil Servant to the birth of Channel 4 as an exciting 'alternative' television channel. Here, acclaimed social historian Stephen Bourne tells the story of the innovation, experimentation, back-tracking and bravery that led British television to help change society for the better.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 336

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated toDrew Griffiths (1947–84)

Cover illustration: A Luna Blue / Alamy Stock Photo

First published 2019

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Stephen Bourne, 2019

The right of Stephen Bourne to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9363 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Foreword by Mark Gatiss

Foreword by Russell T Davies

Acknowledgements

Author’s Note

The Golden Age of British Television

Preface

Out of the Archives

Part 1: 1930s to 1950s

1 Homosexuality, the Law and the Birth of Television

2 Douglas Byng and Auntie

3 Patrick Hamilton’s Rope

4 Stephen Harrison and Edward II

5 Post-War Television and Law Reform

6 Peter Wyngarde and South

Part 2: 1960s

7 On Trial

8 Ena Sharples’ Father

9 John Hopkins and Z Cars (‘Somebody … Help’)

10 The Wednesday Play

11 The Wednesday Play That Got Away

12 Meanwhile, on the ‘Other Side’ (ITV)

13 Soap Gets in Your Eyes

Part 3: 1970s

14 A Handful of Ridiculed Gesticulations

15 Early 1970s Drama

16 Roll on Four O’Clock and Penda’s Fen

17 Upstairs, Downstairs

18 At Home with Larry Grayson?

19 The Naked Civil Servant

20 The Year of the Big Flood

21 Schuman’s Follies

22 Burgess, Blasphemy and Bennett

23 Play for Today: Coming Out

24 Only Connect

Part 4: 1980s

25 Drew Griffiths and Something for the Boys

26 And the Winner is …

27 Auntie’s Dramas

28 EastEnders

29 Two of Us

30 Are We Being Served?

Appendix

Bibliography

About the Author

Foreword by Mark Gatiss

Peter Wyngarde popped my cherry. Not literally, of course, but it was the wildly popular Jason King actor’s startling arrest in a Gloucester bus station in 1975 that set things off. It gave a name to the strange, fuzzy feeling I’d been having for years. The feeling I had when I saw Stuart Damon in The Champions and the lad in Follyfoot. Or the Tomorrow People episode in which the impossibly beautiful Jason Kemp appeared as a fey outsider, bullied by his schoolmates for being different, who was then revealed to be an all-powerful alien in eyeliner. I didn’t know what this feeling was but somehow I knew it was secret and forbidden. I was gay.

When I was growing up, TV was my best friend. I can view the whole of my early life through its prism. A neon tapestry of memories and influences – standing stones and Ogrons and witchcraft and saggy old cloth cats and dystopian futures full of plague and societal breakdown. As I reached adolescence, something else began to make its presence felt. Just as the toy section of the Brian Mills catalogue began to hold less interest than the bit with men’s underwear, certain less whimsical aspects of TV began to dominate my imagination. I’d comb the TV schedules for fragments of anything even remotely poofy. And fragments there were, a sort of 625-line version of real life – a stolen glance here, a delicate brush of the fingertips there – appearing in various plays for today, Rock Follies, foreign films on BBC2, Penda’s Fen (the ultimate 1970s TV experience – folk horror crossed with homosexuality) and Kids with Jason Kemp (again!) as the ‘tart with the golden heart’ in the memorable episode ‘Michael and Liam’.

And then, of course, there was Jason King. As the bestselling author-cum-ladykiller agent, Peter Wyngarde represented the height of early 1970s masculinity, though it’s now hard to fathom with his dandified persona, handlebar ’tache and turned up shirt cuffs. Little did any of us know that Wyngarde was known in the profession as Petunia Winegum and had had a long and tempestuous relationship with fellow heartthrob Alan Bates. But as already stated, his status as housewives’ favourite came crashing to earth in those bus station lavs. I have a vivid memory of this. The papers were full of scandalised headlines and I asked my mam what it was all about. With the deliberateness of speaking unfamiliar words, she said, ‘He’s been caught importuning for men, pet.’ I’m not sure to this day if she really knew what that meant. What’s clear from Stephen Bourne’s terrific, fascinating and compulsively readable book is that Wyngarde had flirted with gay roles – almost hiding in plain sight – for years. He had appeared in Patrick Hamilton’s Rope and then in the intriguing South in 1959, as the tormented Jan, his performance being much praised except by two old ladies who attacked him on a bus: ‘Dirty perv. You should be ashamed of showing such filth on the telly!’ This was followed by his performance as Roger Casement in On Trial, produced by Peter Wildeblood – who’d been imprisoned for his homosexuality and who famously chronicled his experiences in Against the Law.

What Bourne reveals is that these moments, these queer presences, have been with us pretty much since the beginning of TV. From Douglas Byng, the first drag act to appear on television (‘I’m one of the queens of England!’), to live productions of Rope (adapted five times between 1939 and 1957). Inevitably, most of these appearances conformed to stereotype: unhappy, lonely men who often met tragic ends. Though as Bourne points out, performances such as Aubrey Morris’s make-up man in 1962’s Afternoon of a Nymph transcended the cliché. ‘I’d like to be in your shoes,’ he says to his actress friend. Literally or figuratively? Many of these early plays have been wiped, lost forever in the ether, but Stephen Bourne brings them vividly back to life, relating the compelling story of how these fragments of lives, personalities and politics eventually become a flood. Camp family favourites like Larry Grayson, John Inman and Melvyn Hayes (great care was taken to assure viewers that these men weren’t actually homosexual, merely ‘flamboyant’) were joined by the more brazen presence of John Hurt in The Naked Civil Servant, the loving gay couple Rob and Michael in ITV’s Agony and Nigel Havers in the well-remembered Coming Out. Bourne highlights lost gems too, such as the charmingly subversive The Obelisk and Drew Griffiths and Noel Greig’s Only Connect.

Times were changing and we saw the presence of gay men filtering into soaps and other mainstream drama, culminating in EastEnders’ gay couple Colin and Barry. Though criticised as more grey than gay, it’s easy to forget the hostile climate in which these first, faltering steps were made.

The battles are not all won, but what Playing Gay demonstrates – in hugely entertaining and fascinating detail – is how far British broadcasting has come – and come out – into the sunlight.

Foreword by Russell T Davies

Playing Gay is a masterpiece, a meticulous, dazzling, witty and wise history of gay men on television. The range is astonishing – it covers everything from monoliths like The Naked Civil Servant down to every blackmailed husband or secret lover ever to appear on guest spots in Z Cars or Upstairs, Downstairs. And this is an immensely kind piece of work, resurrecting lost classics and forgotten heroes. The chapter on writer Drew Griffiths is achingly sad and compassionate, and restores his career to a much-deserved glory. And this isn’t merely about drama; there’s actual drama within the pages, as executives rage, audiences quiver and stars leap into the fray. Peter Wyngarde emerges as a true champion – and there’s a hilarious meeting between Douglas Byng and Quentin Crisp which deserves to become a TV play in its own right.

Stephen Bourne is one of the soldiers, gatekeepers and champions of our community. I am in awe of his diligence and insight. It’s an honour to see Queer as Folk in there alongside so many other titles, so many of them wrongly forgotten.

Acknowledgements

The late Terry Bolas

David Hankin

Keith Howes

Linda Hull

Molly Hull

Petra Markham

Simon Vaughan

Alexandra Palace Television Society

BBC Written Archives Centre

British Film Institute

British Library

Immediate Media

Author’s Note

From the 1970s to the 1990s we referred to ourselves as the lesbian and gay community. It was not until 1998 that I first heard the term LGBT. Now we are known as the LGBTQI+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning, Intersex) community but, for the purposes of this book, I will be referring to the gay community only, and focussing on how gay men were portrayed on British television in drama and comedy. There isn’t space for actuality (documentary) programmes, though there is enough information in existence for a book to be written about the genre.

Playing Gay in the Golden Age of British TV is partly based on the thesis I submitted for the Master of Philosophy degree which was awarded to me in 2006. My thesis covered the early, formative years of British television from its beginnings in the 1930s to the 1970s. For Playing Gay I have added a section about the 1980s to make it possible to include the birth of Channel 4 in 1982. I also wanted to include the changes that occurred in gay representation throughout that decade until Channel 4 launched the first weekly lesbian and gay series, Out on Tuesday, in 1989. However, there are omissions. For more information I would highly recommend Keith Howes’s Broadcasting It: An Encyclopaedia of Homosexuality on Film, Radio and TV in the UK 1923–1993 (Cassell, 1993).

Though every care has been taken, if, through inadvertence or failure to trace the present owners, I have included any copyright material without acknowledgement or permission, I offer my apologies to all concerned.

The Golden Age of British Television

For the purposes of this book, the ‘Golden Age’ of British television refers to the 1950s through to the 1970s. The 1980s have been included for the advent of Channel 4. Anyone who is interested in the subject of British television history will have their own view of what the ‘Golden Age’ means and the period it covers. Here are some of those views by experts on the subject:

‘Golden ages’ are always partly illusory, seen through the nostalgic rose-tinted spectacle of hindsight. Yet they are often not without some degree of truth – otherwise the myth of a ‘golden age’ would not arise in the first place. As Irene Shubik remarked at a conference on television drama in 1998, the 1960s was a ‘golden age’ because of the autonomy given to writers, directors and producers, an autonomy which was eroded as television became increasingly ‘cost-conscious’ during the 1970s.

Lez Cooke, British Television Drama: A History (BFI Publishing, 2003)

I am not one who speaks of a golden age, as if there are no good programmes made today. I am well aware there are good programmes made in a quantity that was impossible before the present range of channels. But the 60s and 70s were certainly a golden age for producers who knew that, while there were only three channels, there was space for highly creative and challenging programmes. To give but one example: from 1964 the Wednesday Play rode high with a reputation for daring new ideas and styles. BBC1 screened more than 200 such plays in prime time. They caused trouble, brought protests, and had swearing. But they were made within a unique and shared concept of television that has gone.

Joan Bakewell, ‘Enough excuses. The BBC must confront its moral crisis’, The Guardian (20 November 2008)

The notion of a ‘Golden Age’ in any field is usually subjective and difficult to identify in such a sprawling cultural catch-all like television. You could make valid arguments for the 1950s and 1960s to be the ‘Golden Age’ of the television single drama, and equally could justify describing the 2000s as the ‘Golden Age of Reality Television’. But UK TV as a whole? I would have to say the idea of the Golden Age of British Television should encompass a period when the BBC was no longer a monopoly and had to compete, before the multi-channel age diluted the viewing audience … To that end I would elect the 1960s and 1970s – a time when the BBC learned to hit back against the powerful popularity of ITV, when the strength of the single play made television the true ‘National Theatre’ and when viewing figures for the biggest programmes were regularly around the 20 million mark resulting in ‘shared experiences’ for much of the population.

Dick Fiddy, BFI Archive Television Programmer (by email, 21 January 2019)

My golden age of television began in 1952 when our walnut cabineted television set arrived and I watched a Hopalong Cassidy western … I was almost literally glued to the box from that point forward … It became my life and my love. I finally entered superficially sophisticated adulthood with Monitor featuring the early films of Ken Russell and John Schlesinger and the then shockingly irreverent political satire of That Was the Week That Was. The first ‘golden age’ ended with the arrival of Doctor Who in late 1963 … The second ‘golden age’ began almost immediately in 1964 with the advent of BBC2 and the rich seam of single plays which enabled adult themes to be both aired on screen and then discussed at school and at work. Comedy, too, built on the wonderful 1950s legacy of Hancock’s Half Hour which had successfully transferred from radio. The second gilded phase ended in 1969 when I left home finally, fell in love, and made a life beyond the screen until I returned to it to write some of its gay history in the late 1980s.

Keith Howes, author of Broadcasting It: An Encyclopaedia of Homosexuality on Film, Radio and TV in the UK 1923–1993 (Cassell, 1993) (by email, 24 January 2019)

Preface

Television is more interesting than people. If it were not, we should have people standing in the corner of our rooms.

Alan Coren (1938–2007), humanist, writer and satirist

Television is for appearing on – not looking at.

Noël Coward (1899–1973), playwright

On 15 February 2000, I took part in one of Esther Rantzen’s discussion programmes, screened on BBC2. The subject was soap operas and moral issues and I agreed to say something about the portrayal of gay men. As Esther charged at me with her microphone, and a camera zoomed in for my close-up, I composed myself and gasped, ‘Queer as Folk has revolutionised the way gay men are portrayed on British television. There’s no going back to the days when poor Colin had to carry the burden of representation on his shoulders in EastEnders.’ I meant what I said. Until Queer as Folk hit our screens on Channel 4 in 1999, a gay television drama as revealing and sexually explicit as this would not have been possible. For instance, when a gay couple was featured in an ITV play called Friends in 1967, an internal memo was circulated requesting that viewers should be warned about the homosexual theme. In Queer as Folk its openly gay creator and writer Russell T Davies revealed the diversity of gay men’s lives in a stylish, energetic and provocative way. It also succeeded in ‘crossing over’ to a heterosexual audience.

Since Queer as Folk, numerous gay characters have been integrated into mainstream, popular television dramas. However, a few years earlier this wasn’t possible in drama series like The Bill. In 1995, I wrote to an executive producer and asked him if a lesbian or gay police officer could be introduced. His response was not encouraging to say the least, implying that there was no interest in this facet of the officers’ lives and that having gay men ‘hanging around the place’ wouldn’t ‘commend the programme usefully to the public’. Following this executive’s departure from The Bill in 1998, an openly gay officer, Sergeant Craig Gilmore, played by Hywel Simons, was introduced on 10 April 2001.

Coronation Street, after forty-three years on the air, caught up in 2003. British television has definitely moved on from the days when a popular soap opera could only offer us Crossroads’ prissy chef Mr Booth, who was forever mincing after motel owner Meg Richardson, and complaining about the price of fish. However, it would be wrong to assume that Queer as Folk is the only worthwhile gay British television drama from the past. There has been a gay presence on television since the BBC transmitted its pre-war service live from Alexandra Palace in the late 1930s, and some of the programmes have been groundbreaking.

When I was growing up and watching television in the 1960s and 1970s it seemed gay men only existed on television to be laughed at, and I cringed with embarrassment when everybody else laughed at the camp entertainer Larry Grayson and actor John Inman, who played the effeminate Mr Humphries in BBC1’s popular situation-comedy series Are You Being Served? Then John Hurt gave us his acclaimed portrayal of Quentin Crisp in The Naked Civil Servant (1975), and at last I felt we were being taken seriously. However, from the standpoint of an isolated and closeted working-class teenager, which I was in the 1970s, gay men did not exist and I often felt I was the only one.

My mother introduced me to television when I was just 2 years old. She plopped me in front of Andy Pandy and she later told me that I was mesmerised. She had no fear of leaving me alone in the living room with Andy Pandy, Looby Loo and Teddy. An earthquake wouldn’t have budged me. One of my earliest memories is witnessing the death of Martha Longhurst in Coronation Street in 1964. She had a heart attack in the Rovers Return and died clutching her glasses with one hand and a pint of milk stout with the other. I had never seen a dead person before so, naturally, I was upset. I was only 6 years old. I was 9 years old on 27 July 1967 when the Sexual Offences Act became law. I was too young to understand what this meant but I was fascinated by ‘Auntie’ Val Singleton making something interesting out of sticky-back plastic in Blue Peter. In 1967, I was a happy little boy growing up in a loving, caring, working-class family. In our home, a council flat on a housing estate on Peckham Road, my sister and I watched a lot of television. Years later, when I made friends with middle-class people, I discovered that their parents either restricted their television viewing or banned it in their homes altogether. So, my middle-class friends had no idea who Squiddly Diddly was, but my working-class friends did! In the 1960s my television viewing was broad and included almost everything from Ken Loach’s hard-hitting Cathy Come Home (1966), about the pain and humiliation of homelessness, to the wonderful science fiction drama series Doctor Who, which traumatised one of my cousins – every time he saw a Dalek he hid, shaking with fear, behind the settee.

At my secondary modern school in the early 1970s, I was identified as a ‘poof’ and bullied for it. It was a horrible time, but television provided a way to escape the trauma of homophobic bullying. Coronation Street continued to be a favourite along with Timeslip, A Family at War, Upstairs, Downstairs and many others. In the 1970s Gay Liberation happened, but not in Peckham where I grew up. Gay News was on sale, but I never saw a copy. Though I was bullied at school for being a ‘poof’, I suffered in silence. There was no one to talk to. The victimisation I suffered couldn’t be reported to the police, because I was terrified of them, and they were considered homophobic anyway. I did not find the courage to ‘come out’ (discuss my sexuality) until I was 22, but I escaped reality by watching lots of television, and I absorbed everything I could about gay images.

In 1985, when I went to the London College of Printing at the Elephant and Castle to study for a degree in film and television, I was very knowledgeable about television history. It proved to be of great use when my interest in researching how gay men had been portrayed in television expanded. In 1986, I visited the Hall Carpenter Archives to research a college essay on gay men in television. To my delight I discovered Keith Howes’s superb and informative two-part survey of lesbians and gays in British television. Keith had put this together for the bi-weekly newspaper Gay News in 1977.

After I graduated in 1988, I was employed as a Research Officer by the British Film Institute (BFI) and the BBC on a project they funded jointly, which documented race and representation in British television from 1936 to 1989. Consequently, I discovered that the history of people of African and Caribbean descent on British television was vastly different from the one which had been previously understood and accepted. There were, it turned out, many more programmes featuring black people in the early years than we anticipated. With ongoing support from the BFI and the BBC we, the research team, pieced together the history. The range and depth of programmes we rediscovered – especially those made in the 1950s and 1960s – was surprising. Themes explored included decolonisation, the settlement of Africans and Caribbeans in post-war Britain, and mixed marriages. Racism was hardly absent. From 1958 to 1978 the progressive, cutting-edge programmes co-existed alongside the BBC’s offensive Black and White Minstrel Show. However, I learned from this experience not to make assumptions about the historical portrayal of minority groups on the box, including gay men. There have always been positive exceptions to the rule.

In July 1992, my research into gays in television led to the launch of Out of the Archives: Lesbians and Gays on TV at the National Film Theatre (NFT; now known as BFI Southbank). This was a collection of lesbian- and gay-themed British television programmes. Working with Veronica Taylor in the BFI’s Television and Projects Unit, I had already programmed the NFT’s first black British television season, Black and White in Colour, in April 1992. Both seasons were curated under the umbrella of Television on the South Bank, a series of screenings which had been launched at the NFT in 1991.

Out of the Archives took place on four Tuesdays at the Museum of the Moving Image (now known as NFT3). They included the extraordinary Joe Orton play Entertaining Mr Sloane (1968), Howard Schuman’s clever satire The British Situation: A Comedy (1978), On Trial: Oscar Wilde (1960), and Blasphemy at the Old Bailey (1977), the BBC drama documentary about the Gay News blasphemy trial. They were shown with two lesbian-themed dramas, Country Matters: Breeze Anstey (1972) and Second City Firsts: Girl (1974). Girl sold out in spite of a warning given to the audience that the only copy that we could find was technically imperfect. It didn’t deter the audience, which included a number of older lesbians who fondly remembered seeing this landmark television play in 1974. It starred a young Alison Steadman as an army recruit who is seduced by a WRAC she-wolf! The season’s other highlight was Only Connect (1979), a superb original drama written by two brilliant Gay Sweatshop writers, Drew Griffiths and Noel Greig.

Out of the Archives was so popular with audiences that I was invited to return the following year for a second season. Meanwhile, the BFI sent me on a UK tour of their regional cinemas with some of the programmes. The tour kicked off with a visit to Edinburgh on 22 February 1993, followed by Tyneside, Wolverhampton, Leicester, Hull, Manchester and Nottingham. I presented an illustrated talk followed by a screening of Only Connect.

This was groundbreaking work. Veronica gave me complete freedom to research the programmes and put them together. When the third Out of the Archives was showcased in July 1994, Keith Howes’s indispensable Broadcasting It: An Encyclopaedia of Homosexuality on Film, Radio and TV in the UK 1923–1993 had been published. It proved to be a magnificent 1,000-page reference book. When I interviewed Keith for Capital Gay (8 April 1994) he told me: ‘Television and radio are as good as film, theatre, sculpture, painting and any of the other arts but they are totally neglected and derided in this country.’ For Keith, Broadcasting It was a labour of love:

Years ago, people never talked about television. It was disposable. It was irrelevant. And gays and lesbians always believed that we were invisible on the box or stereotyped and that is just not true. That’s one of the reasons I did Broadcasting It. I grew tired of walking into gay bookshops and asking for books on television and being told, ‘Yes, we have The Celluloid Closet by Vito Russo.’ Also, I never sensed from gays and lesbians that they felt this was in any way an omission or a gap. I couldn’t accept that. Now I find young people are passionately interested in the subject and can talk to me for hours about what they have seen.

I continued to programme Out of the Archives annually – every July – for ten seasons until the final event in 2001. When television producer Stephen Jeffery-Poulter hosted a tribute to the writer Howard Schuman during the fifth season in 1996, he explained to the audience their importance and relevance:

I would just like to say a few words about these unique retrospective seasons. For the last five years Out of the Archives has showed a remarkable range of lesbian and gay programming exhumed for our edification and entertainment by cinema and television historian Stephen Bourne, whose efforts have been largely unsung.

It is hard to underestimate the importance of this work. Lesbian and gay history and culture has, until very recently, been a hidden and secret one. Hardly surprisingly, as gay men were persecuted as criminals until 1967 and lesbians were almost literally invisible. Throughout history the individual contributions of lesbians and gay men to British society have been systematically denied, distorted or suppressed.

It’s only in the last twenty-five years with the emergence of an identifiable lesbian and gay community that the daunting task of reclaiming our heritage has become possible. During that same period television has become the all-pervasive mass medium shaping the political, social and moral perspectives of this country’s citizens.

By studying the way in which lesbians and gay men have been portrayed by television we can begin to understand the many subtle and not-so-subtle ways in which the great British public have been taught to perceive us – and how we have consciously and sub-consciously learned to define ourselves in relation to those images.

The screening of these archive programmes has exposed the negative and stereotypical images of lesbians and gays which, until very recently, were the predominant ones portrayed by television and which have fuelled the homophobia and discrimination which are still so rife in our society. However, the seasons have also celebrated the few precious occasions when, more or less accidently, certain honest representations of lesbian and gay lifestyles or individuals did make it to the small screen. They have also provided a rare opportunity for some of the creative talents of lesbians and gay men involved in television to talk about their unique contribution to the medium.

In this way Out of the Archives has been successfully unearthing, reclaiming and interpreting a lost heritage and thereby bequeathing it to future generations. We can now use this knowledge to challenge and encourage today’s programmers to reflect more realistically the broad and growing sexual diversity of modern British society.

Throughout the 1990s, television plays with gay leading characters, or prominent gay themes, were rarely seen. Admittedly, during this period, the output of television drama had diminished – or in some people’s view had been ‘dumbed down’. The production of single plays on television was reduced but there were a handful that were produced and explored the diversity of gay life with three-dimensional characters and contemporary themes relevant to gay men in Britain. They included three by gay writers: Sean Mathias’s The Lost Language of Cranes (BBC2, tx 9 February 1992), adapted from David Leavitt’s novel; Howard Schuman’s Nervous Energy (BBC2, tx 2 December 1995); and Kevin Elyot’s My Night With Reg (BBC2, tx 1 March 1997). Their work was a far cry from Patrick Hamilton’s Rope, made by the BBC sixty years earlier.

Meanwhile, Keith Howes, Stephen Jeffery-Poulter and myself collaborated on a proposal for a television documentary about the history of gay men in British television. There had already been a two-part documentary about the history of black (African Caribbean) people in British television called Black and White in Colour (BBC2, tx 27 and 30 June 1992), on which I worked as a researcher. This was followed by A Night in With the Girls (BBC2, tx 15 and 16 March 1997), a two-part documentary celebrating the contribution made by women to the development of British television. It seemed only natural to have a similar archive and interview-based documentary about gays. Regrettably our proposal was rejected by everyone we took it to, including the BBC and Channel 4. I was disappointed, but in 1999 I began a Master’s degree at De Montfort University. The subject of my thesis was the representation of gay men in British television drama from the 1930s to the 1980s. This enabled me to continue my exploration of the subject and to put it to good use. In 2006, I completed the thesis and was awarded a Master of Philosophy degree. Though I tried to get it published, it took twelve years to find a publisher. Thanks to The History Press, it has happened.

Out of the Archives

I am proud of Out of the Archives. I was thrilled that, in 2013, Play of the Week: South (1959) (see Chapter 6), the earliest known surviving gay television drama, was shown again at the BFI’s 27th Lesbian and Gay Film Festival. Unfortunately, in their publicity for the screening, they claimed it was being shown for the first time since 1959. My rediscovery of the play in the 1990s and the inclusion of it in Out of the Archives in 1998 was completely overlooked. Four years later, in July 2017, South was shown again at BFI Southbank when the curator Simon McCallum included it in his season Gross Indecency: Queer Lives Before and After the ’67 Act. On this occasion Peter Wyngarde, the star of South, participated in a Q&A after the screening. Other highlights from Out of the Archives which were included by Simon in this season were On Trial: Oscar Wilde (see Chapter 7), Horror of Darkness (see Chapter 10), This Week: Homosexuals (1964), This Week: Lesbians (1965), Man Alive (1967) and Edward II (1970) (see Chapter 15).

The following is a list of the all the programmes and special events I curated for the National Film Theatre for Out of the Archives from 1992 to 2001:

1992

On Trial: Oscar Wilde (Granada 1960); Entertaining Mr Sloane (Association Rediffusion 1968); Country Matters (‘Breeze Anstey’) (Granada 1972); Second City Firsts (‘Girl’) (BBC 1974); Sex in Our Time: For Queer Read Gay (Thames 1976); Everyman: Blasphemy at the Old Bailey (BBC 1977); The London Weekend Show (‘Young Lesbians’) (LWT 1977); The British Situation: A Comedy (Thames 1978); The Other Side (‘Only Connect’) (BBC 1979) plus extracts from Gays: Speaking Up (Thames 1978); Agony (LWT 1979); and Gay Life (LWT 1981).

1993

The Wednesday Play (‘Horror of Darkness’) (BBC 1965); Man Alive (BBC 1967); Within These Walls (‘One Step Forward, Two Steps Back’) (LWT 1974); Second City Firsts (‘Girl’) (BBC 1974); World in Action (‘Coming Out’) (Granada 1975); Play for Today (‘The Other Woman’) (BBC 1976); Play of the Month (‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’) (BBC 1976); Premiere (‘A Hymn from Jim’) (BBC 1977); Premiere (‘The Obelisk’) (BBC 1977); and Play for Today (‘Coming Out’) (BBC 1979); plus a special event At Home with Larry Grayson? presented by Andy Medhurst including extracts from Shut That Door!, The Generation Game and At Home with Larry Grayson.

1994

Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime (ABC 1960); The Importance of Being Earnest (ABC 1964); This Week (‘Lesbians’) (Associated Rediffusion 1965); Within These Walls (‘For Life’) (LWT 1975); Crown Court (‘Lola’) (Granada 1976); Rebecca (BBC 1979); The House on the Hill (‘Something for the Boys’) (Scottish TV 1981); BBC Television Shakespeare (‘Coriolanus’) (BBC 1984); plus extracts from Z Cars (‘Friends’), Dixon of Dock Green, Juke Box Jury and Rachel and the Roarettes and a special event Screened Out: Lesbians and Television presented by Rose Collis.

1995

Monitor (‘Benjamin Britten – Portrait of a Composer’) (BBC 1958); Steptoe and Son (‘Any Old Iron?’) (BBC 1970); Crown Court (‘Heart to Heart’) (Granada 1979); The Lost Language of Cranes (BBC 1992); Gays: Speaking Up (Thames 1978); plus three special events: Come Together presented by Stephen Jeffery-Poulter with extracts from Press Conference: Wolfenden (BBC 1957, This Week (‘Homosexuals’) (Associated Rediffusion 1964), Panorama (BBC 1971), Measure of Conscience (BBC 1972); A Tribute to Larry Grayson with At Home with Larry Grayson (LWT 1983) and extracts from Parkinson (BBC 1978), and The Good Old Days (BBC 1983); and An Englishman and a Heterosexual: A Look Back in Anger at John Osborne presented by Keith Howes with You’re Not Watching Me, Mummy (Yorkshire TV, 1980).

1996

Nureyev (BBC 1974); Nijinsky ‘God of the Dance’ (BBC 1975); Crown Court (‘Lola’) (Granada 1976); and Grapevine (‘Gay Sweatshop’) (BBC 1979) plus three special events: Jackie Forster interviewed by Rose Collis; Howard Schuman interviewed by Stephen Jeffery-Poulter; and In the Life: Black Lesbians on British TV with extracts from Agony, EastEnders, Claire Rayner’s Casebook, Framed Youth, Kilroy, Arena Cinema and three programmes from Channel 4’s Out series: Double Trouble, Khush and BD Women.

1997

On Trial: Sir Roger Casement (Granada 1960); On Trial: Oscar Wilde (Granada 1960); Nancy Spain presented by Rose Collis with The Touch (BBC 1956) and Juke Box Jury (BBC 1960); Screen Two: Inappropriate Behaviour (BBC 1987); City Shorts: Came Out, It Rained, Went Back in Again (BBC 1991); plus James Baldwin with screenings of Bookstand (BBC 1963), Bookmark (BBC 1984), Frank Delaney (BBC 1984), Ebony (BBC 1985) and Mavis on 4 (C4 1987); and a special event ’60s Divas with extracts from Judy and Liza at the Palladium (ATV 1964), Show of the Week: Shirley Bassey (BBC 1966), Dusty (BBC 1967), Once More with (Julie) Felix (BBC 1967) and Sandie Shaw (BBC 1968).

1998

Play of the Week (‘South’) (Granada 1959); Total Eclipse (BBC 1973); Belles (BBC 1983); If They’d Asked for a Lion Tamer (C4 1984); Black Divas (C4 1996); plus two special events: Mary Morris with screenings of The Andromeda Breakthrough (BBC 1962) and The Spread of the Eagle (BBC 1963) and ’70s Divas with extracts including Roberta Flack, Joan Armatrading, Suzi Quatro, Bette Midler, Shirley Bassey, The Three Degrees, Amii Stewart, Gloria Gaynor, Diana Ross and Cilla Black.

1999

Me, I’m Afraid of Virginia Woolf (LWT 1978) and An Englishman Abroad (BBC 1983) plus three special events: Black Divas (C4 1996); A Tribute to Jackie Forster which included Speak for Yourself (LWT 1974), The Day That Changed My Life (BBC 1997) and Gay Life (LWT 1981); and Lesbians: Vision On which included Out on Tuesday (‘Lust and Liberation’) (C4 1989), City Shorts: Came Out, It Rained, Went Back in Again (BBC 1991), The Late Show (‘Dorothy Arzner’) (BBC 1993), A Woman Called Smith (BBC 1997) and Dusty at the BBC (BBC 1999).

2000

Armchair Theatre: Afternoon of a Nymph (ABC 1962); In Camera (BBC 1964); The Other Side (‘Connie’) (BBC 1979); and Wild Flowers (C4 1990); plus Derek Jarman with screenings of Books By My Bedside (Thames 1989), Derek Jarman – A Portrait (BBC 1991), Building Sites (BBC 1991), and Face to Face (BBC 1993), as well as one special event Not in Front of the Viewers, an illustrated talk presented by Stephen Bourne with a screening of Only Connect (BBC 1979) introduced by W. Stephen Gilbert.

2001

Edward II (BBC 1970); The Important Thing is Love (ATV 1970); Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit (BBC 1990); plus one special event Soap Queens including Violet Carson in Stars on Sunday (Yorkshire TV 1972), Pat Phoenix in Parkinson (BBC 1975), an early episode of Crossroads (ATV 1968), and Noele Gordon on Russell Harty (BBC 1981).

1

Homosexuality, the Law and the Birth of Television

When the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) began broadcasting in 1922 (radio only; television followed in 1936) it did not consider homosexuality a subject that was fit for public discussion. In Britain, sexual relationships between men remained against the law until 1967. In that year, the Sexual Offences Act partially decriminalised homosexual acts. However, the ways such men are described is relatively new. Today, the term LGBTQI+ is considered inclusive and it is frequently used, but in the early part of the twentieth century the word ‘homosexual’ was still uncommon, and used mostly by academics or doctors. Admittedly it was a time of innocence about sex in general, but homosexuality was not discussed in families, or taught in schools. In 1992, James Gardiner explained some of the reasons for this ‘silence’ in his book A Class Apart: The Private Pictures of Montague Glover:

In Great Britain before 1885, homosexual acts were not directly legislated against, but fell within the scope of the 1533 Act of King Henry VIII which made the ‘detestable and abominable Vice of Buggery committed with mankind or beast’ a criminal act punishable with ‘death and losses and penalties of their goods chattels debts lands and tenements’.1

The 1533 Act remained in substance on the Statute Book until 1967. The last execution for ‘homosexual buggery’ took place in 1832, and the death penalty for the crime was not abolished until the 1861 Offences Against the Person Act. After 1861, men who were proved to have had sex with other men were imprisoned for life. With the passing of the notorious Labouchere Amendment in 1885, all homosexual activity became a criminal offence and punishable by terms of up to two years’ imprisonment with hard labour.

Gardiner added: ‘in Victorian England homosexuality was considered a great evil by society at large, an unmentionable horror. The word homosexual was not even invented until 1869 and, together with its contemporary equivalent ‘invert’, was considered unprintable.’2 Prosecutions were seldom reported in the press. Only the most sensational cases, involving members of the aristocracy or public figures, were highlighted, and even then with no real detail. The popular dramatist Oscar Wilde was the first ‘celebrity’ to become a victim of the 1885 Labouchere Amendment and, if his trials were widely reported, it was only to expose his ‘consummate wickedness and show where the paths of such debauchery (particularly consorting socially with the working-classes) might lead.’3 As far as the medical profession was concerned, homosexuality was considered at best a mental sickness, and one that could be ‘treated’ by aversion therapy. Men who were attracted to their own sex had little choice but to view themselves as sick and abnormal, social pariahs and perverts. For decades gay men referred to heterosexual men as ‘normal’, thus excluding themselves from any claim to normality.

Until the 1960s it was considered unthinkable for a gay man to be interviewed on television. That changed with two prominent actuality series: ITV’s This Week (1964) and the BBC’s Man Alive (1967). By the 1990s attitudes had changed, and in 1997 a range of lesbian and gay interviewees were seen on BBC television in the series It’s Not Unusual