13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

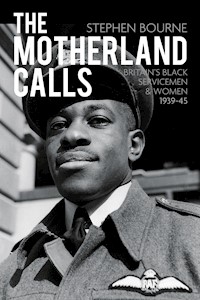

During the Second World War, black volunteers from across the British Empire enthusiastically joined the armed forces and played their part in fighting Nazi Germany and its allies. In the air, sea and on land, they risked their lives, yet very little attention has been given to the thousands of black British, Caribbean and West African servicemen and women who supported the British war effort from 1939–45. Drawing on the author's expert knowledge of the subject, and many years of original research, The Motherland Calls also includes some rare and previously unpublished photos. Among those remembered are Britain's Lilian Bader, Guyana's Cy Grant, Trinidad's Ulric Cross, Nigeria's Peter Thomas, Sierra Leone's Johnny Smythe and Jamaica's Billy Strachan, Connie Mark and Sam King. The Motherland Calls is a long-overdue tribute to some of the black servicemen and women whose contribution to fighting for peace has been overlooked. It is intended as a companion to Stephen Bourne's previous History Press book: Mother Country – Britain's Black Community on the Home Front 1939–45.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Black and Asian Studies Association

BBC Written Archives Centre

British Film Institute (www.bfi.org.uk)

British Library (www.bl.uk)

Commonwealth War Graves Commission (www.cwgc.org)

Imperial War Museum (London) (www.iwm.org.uk)

London Borough of Southwark Libraries

West Indian Ex-Services Association

www.caribbeanaircrew-ww2.com

Nadia Cattouse

Sean Creighton

Neil Flanigan MBE (President, West Indian Ex-Services Association)

Steven Hatton (Director, Into the Wind)

Keith Howes

Linda Bourne Hull

Deborah Joyce

Professor David Killingray

Sam King MBE

Barnaby Phillips (Director, The Burma Boy)

Laurent Phillpot (Archivist, West Indian Ex-Services Association)

Francesca Pratt (Stock Services, Southwark Libraries)

Marika Sherwood (Senior Researcher, Institute of Commonwealth Studies)

Aaron Smith

Robert Taylor

Patrick Vernon (Director, Speaking Out & Standing Firm and A Charmed Life)

CONTENTS

Title

Acknowledgements

Author’s Note

Statistics

Introduction

Part I: Britain

1 ‘Joe’ Moody: An Officer & an Englishman

2 Sid Graham: The Call of the Sea

3 Lilian & Ramsay Bader: Life in the Forces

4 Amelia King & the Women’s Land Army

5 Musicians in Battledress

Part II: Guyana & the Caribbean

6 Cy Grant: Into the Wind

7 Billy Strachan: A Passage to England

8 Ulric Cross: A Fine Example

9 Connie Mark: A Formidable Force

10 Sam King: RAF to Windrush

11 Norma Best & Nadia Cattouse: Lest We Forget

12 Eddie Martin Noble & A Charmed Life

13 Allan Wilmot: Making a Difference

14 Baron Baker: A Founding Father

15 Cassian Waight & the ‘League of Nations’

Part III: Africa

16 Peter Thomas: The First of the Few

17 Johnny Smythe: A Veteran with Attitude

18 Isaac Fadoyebo: The Burma Boy

Part IV: African Americans

19 ‘They’ll bleed and suffer and die’

Postscript: In Memoriam

Appendix I

A Short History of the West Indian Ex-Services Association

Appendix II

‘From War to Windrush’ (Imperial War Museum, London)

Appendix III

Film, Television and Radio

Appendix IV

Extracts from the Wartime Newsletters of the League of Coloured Peoples

Further Reading

About the Author

Plates

Copyright

AUTHOR’S NOTE

In The Motherland Calls the terms ‘black’ and ‘African-Caribbean’ refer to Caribbean and British people of African origin. Other terms, such as ‘West Indian’, ‘negro’ and ‘coloured’ are used in their historical contexts, usually before the 1960s and 1970s, the decades in which the term ‘black’ came into popular use.

This book’s purpose is as an introduction to the subject; it is not intended to be definitive; the reader will find gaps.

For information about the Home Front the reader should consult my previous book, Mother Country: Britain’s Black Community on the Home Front, 1939–45 (The History Press, 2010).

The Motherland Calls should not be read in isolation. Since the 1980s several books have been published about the lives of black servicemen and women in the Second World War. Some of these are now out of print, but I would suggest that readers access them through interlibrary loans, the British Library, or a second-hand book dealer, such as www.abebooks.co.uk. I would highly recommend the following: Ben Bousquet and Colin Douglas’s West Indian Women at War: British Racism in World War II (1991); Oliver Marshall’s The Caribbean at War: British West Indians in World War II (1992); and Robert N. Murray’s Lest We Forget: The Experiences of World War II West Indian Ex-Service Personnel (1996). Angelina Osborne and Arthur Torrington’s We Served: The Untold Story of the West Indian Contribution to World War II (2005) and Eric Myers-Davis’s Under One Flag:How indigenous and ethnic peoples of the Commonwealth and British Empire helped Great Britain win World War II (2009), aimed at younger readers, are extremely useful and beautifully produced.

Autobiographies or memoirs written by black ex-servicemen and women are harder to find, but the exceptions include: E. Martin Noble’s Jamaica Airman: A Black Airman in Britain 1943 and After (1984); Lilian Bader’s Together: Lilian Bader: Wartime Memoirs of a WAAF 1939–1944 (1989); Dudley Thompson’s From Kingston to Kenya: The Making of a Pan-Africanist Lawyer (1993); Sam King’s Climbing Up the Rough Side of the Mountain (1998); Isaac Fadoyebo’s A Stroke of Unbelievable Luck (1999); and Cy Grant’s ‘A Member of the RAF of Indeterminate Race’: WW2 experiences of a former RAF navigator and POW (2006).

The experiences of African American GIs in Britain from 1942–45 have been extensively covered by Graham Smith in When Jim Crow Met John Bull: Black American Soldiers in World War II Britain (1987). For West Indians and others, readers may want to consult the works of Marika Sherwood, including her book Many Struggles: West Indian Workers and Service Personnel in Britain (1939–1945) (1985); as well as back issues of the newsletters of the Black and Asian Studies Association, co-founded in 1991 by Marika Sherwood, Stephen Bourne and several other historians of black Britain. The experiences of Africans in wartime have been covered extensively by Professor David Killingray in several books, including his comprehensive Fighting for Britain: African Soldiers in the Second World War (2010). See also Roger Lambo’s excellent chapter, ‘Achtung! The Black Prince: West Africans in the Royal Air Force 1939–46’ in Africans in Britain (1994), edited by Professor David Killingray.

Joanne Buggins’s ‘West Indians in Britain during the Second World War: a short history drawing on Colonial Office papers’, published in the Imperial War Museum Review No. 5 (1990), is highly recommended.

The following website is an invaluable source of information on Caribbean aircrew in the Second World War: www.caribbeanaircrew-ww2.com.

Several exhibitions have made important contributions to documenting the experiences of black servicemen and women, and these include ‘Butetown Remembers World War II: Seamen, the Forces, Evacuees’ at the Butetown History and Arts Centre, Cardiff Bay (15 March – 3 July 2005) and ‘From War to Windrush’ at the Imperial War Museum, London (13 June 2008 – 29 March 2009) (see Appendix II). The Royal Air Force Museum in London (www.rafmuseum.org.uk) has a permanent exhibition on display that acknowledges ethnic diversity in the RAF in the Second World War.

Though every care has been taken, if, through inadvertence or failure to trace the present owners, I have included any copyright material without acknowledgement or permission, I offer my apologies to all concerned.

STATISTICS

Exact statistics of the number of black men and women from Britain, the Caribbean and Africa who served in the British armed services during the Second World War, or contributed to the war effort, are impossible to determine. Ethnicity was not automatically recorded and no official records of all those working in the many fields of production for the war effort were kept.

Juliet Gardiner, author of Wartime Britain 1939–1945 (2004), claims that on the day war broke out, 3 September 1939, there were no more than 8,000 black people living in Britain. However, some historians of black Britain have suggested a much higher figure, including Dr Hakim Adi (around 15,000).1 The recruitment of black people from the colonies into the war effort changed this situation but, without official figures, estimates vary.

In 1995, using a variety of Colonial Office sources, Ian Spencer estimated in his contribution to War Culture that, of British Caribbeans in military service during the war, 10,270 were from Jamaica, 800 from Trinidad, 417 from British Guiana, and a smaller number, not exceeding 1,000, came from other Caribbean colonies. The majority served in the RAF.2

In WeWereThere, published in 2002 by the Ministry of Defence, it is claimed:

At the end of the war over three million men [from various parts of the British Empire] were under arms, 2.5 million of them in the Indian Army, over 200,000 from East Africa and 150,000 from West Africa. The RAF also recruited personnel from across the Commonwealth. At first, recruitment concentrated on British subjects of European descent. However, after October 1939 questions of nationality and race were put aside, and all Commonwealth people became eligible to join the RAF on equal terms. By the end of the war over 17,500 such men and women had volunteered to join the RAF, in a variety of roles, and a further 25,000 served in the Royal Indian Air Force.3

In 2007 Richard Smith noted in The Oxford Companion to Black British History:

From 1941 the British government began to recruit service personnel and skilled workers in the West Indies for service in the United Kingdom. Over 12,000 saw active service in the Royal Air Force … About 600 West Indian women were recruited for the Auxiliary Territorial Service, arriving in Britain in the autumn of 1943. The enlistment of these volunteers was accomplished despite official misgivings and obstruction.4

In 1995 the Imperial War Museum produced ‘Together’, a multimedia resource pack on the contribution made in the Second World War by African, Asian and Caribbean men and women. In the pack’s introduction it is noted that there are no exact statistics for the number of men and women of African, Caribbean and Asian origin who served in the British forces during the war, but it does offer the most accurate information that could be found at that time on the numbers of black wartime personnel.

WEST INDIES

Several thousand West Indians were recruited into the British war effort. Nearly 6,000 served with the RAF, 5,536 as ground staff and 300 as aircrew. Thousands more served in the merchant navy and in civilian war work in Britain, 350 of them in munitions. Approximately 700 British Hondurans came and worked as lumberjacks in Scotland. In addition, 40,000 West Indians were recruited for work in the USA.

Early in 1940, 1,800 responded to a Colonial Office request for merchant seamen. In 1942 there was a call for skilled engineers. In the army there had been a colour bar, but it was relaxed for the war and some West Indians joined the Royal Engineers in 1941. There were, however, disagreements between the Colonial Office, who favoured recruiting West Indians, and the Secretary of State for War, who was reluctant. In 1944 a Caribbean Regiment was raised, comprising 1,000 soldiers, and after training they were sent overseas but never actually saw active service.

The most significant contribution was in the RAF. Some West Indians trained with the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) before coming to Britain. Between 1940 and 1942, 3,000 enlisted in the RAF and between June and November 1944, nearly 4,000 ground staff arrived in Britain. A further 1,500 came over in March 1945. Of those serving in the RAF and RCAF, 103 were decorated.

On a smaller scale, women also played a part. The reluctance of the War Office to recruit women from the West Indies explains the relatively small number, but 80 joined the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) and 30 the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS).5

AFRICA

The total number of Africans who fought for Britain in the Second World War is approximately 372,000: 119,000 were under South-East Asia Command (SEAC) – 46,000 East Africans and 73,000 West Africans; 47,500 Africans served in the Middle East – 31,000 of them East Africans and 16,500 of them West Africans; a further 206,000 served in the Home Commands in Africa – 150,000 of them East Africans and 56,000 of them West Africans.

The two main forces fighting for Britain were the King’s African Rifles (KAR) and the Royal West African Frontier Force (RWAFF, known as Waff). A large number of KAR battalions, raised from Uganda, Kenya, Tanganyika, Nyasaland and Somaliland, took part in three major campaigns of the war: the defeat of the Italians in Somaliland and Abyssinia, 1940–41; the occupation of Madagascar against the Vichy French in 1942; and the re-conquest of Burma against the Japanese in 1944 and 1945. It was the first time that KAR battalions had fought outside the continent of Africa. Originally deployed to fight the Italians in East Africa, the askaris (local troops) of the KAR were available for other battlefronts after the defeat of the Italians. The entry of Japan into the war made it necessary to recruit larger forces to fight them in the Far East. By May 1942 there were 28 battalions operating overseas. Over 12,000 members of the 11th East African Division were front-line troops in the Burma Campaign. The sickness rate of East African troops was lower than that of other contingents and they adapted well to the wide variety of climates and terrains that faced them.

In addition, 10,000 Bechuana (from what is now Botswana) volunteered for service with the British Army and served in Syria, Egypt, Sicily, Italy and the Middle East. Forty-five of them were given honours or awards.

The RWAFF also played an important part in the Second World War, firstly in the Abyssinian Campaign of 1941, and later in the Burma Campaign of 1943–44. 81 West African Division consisted of three brigades: one from Nigeria, one from the Gold Coast and one from Sierra Leone. They were trained in jungle warfare before being sent to India in September 1943 and thence to Burma. In 1944 a further division of West African troops was formed, the 82 (WA) Division, and these operated with the Indian XV Corps during the next campaign in Arakan, Burma. The West African troops in Burma were renowned for their discipline and there were awards for bravery and gallantry: one soldier was given the British Empire Medal (BEM), three the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM), eleven the Military Medal (MM) and seventeen were Mentioned in Despatches.6

Notes

1 See Stephen Bourne, Mother Country: Britain’s Black Community on the Home Front, 1939–45 (The History Press, 2010), p. 135.

2 Ian Spencer, ‘World War Two and the Making of Multi-Racial Britain’, in War Culture: Social Change and Changing Experience in World War Two, ed. Pat Kirkham and David Thoms (Lawrence and Wishart, 1995), p. 212.

3We Were There: For 200 years ethnic minorities have fought for Britain all over the world (Director General Corporate Communications/Ministry of Defence, 2002), p. 13.

4 Richard Smith, ‘Second World War’, The Oxford Companion to Black British History (Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 436–7.

5 Imperial War Museum, ‘Together’.

6 Ibid.

INTRODUCTION

‘We did a damn good job and when Winston Churchill said “Never was so much owed by so many to so few” I’m proud to say I am one of the few.’

Baron Baker (RAF) in The Invisible Force (BBC Radio 4, 16 May 1989)

In 2002, when the bestselling author Ken Follett published his wartime espionage thriller Hornet Flight, he wasn’t expecting criticism for including a black Royal Air Force (RAF) squadron leader in his novel. The squadron leader, Charles Ford, is featured in the prologue with a Caribbean accent ‘overlaid with an Oxbridge drawl’.1 One of Follett’s severest critics was Alan Frampton, who served as a pilot in the RAF between 1942 and 1946. Writing to Follett from his home in Zimbabwe, Frampton said Ford was ‘not a credible character’ and that his inclusion was a ‘sop’ to black people who may read Hornet Flight. An angry Frampton apparently threw down the book in disgust when he came across the Ford character.

In his letter to Follett, Frampton said:

For the life of me I cannot recall ever encountering a black airman of any rank whatsoever during the whole of my service, which included Bomber Command. This may have been a coincidence of course but, in England sixty years ago, blacks were few and far between amongst the population and race was not an issue, unlike today with its attendant racial tensions and extreme sensitivity amounting almost to paranoia. He certainly aroused my indignation, remembering as I do, the real heroes of that period in our history, who were not black. I regard myself as a realist but certainly not an apologist for my race. I have read several of your books and enjoyed them. This one I threw down in disgust.

In his reply to Frampton, dated 19 November 2003, Ken Follett explained:

I’m afraid you’re mistaken. The character Charles was inspired by the father of a friend of mine, a Trinidadian who flew eighty sorties as a navigator in the Second World War and reached the rank of squadron leader. He says there were 252 Trinidadians in the RAF, most of them officers. He was the highest ranked during the war, although after the war a few reached wing commander. He received the DFC and the DSO. With true-life heroes as he, there’s no need for a ‘sop’ to black people, really, is there?

The Trinidadian who inspired Follett is Ulric Cross (see Chapter 8) whose response to Frampton was also put on record: ‘He must be living in a strange world. I am old enough to have a certain amount of tolerance. People believe what they need to believe. For some reason Frampton needs to believe that. When you know what you have done, what people think is irrelevant.’2

Some may view Alan Frampton’s outburst as racist, but it should be taken into account that, with the erasure of black servicemen and women from the history books, Frampton probably had no way of knowing that black RAF officers, like Ulric Cross, existed. After 1945 historians of the Second World War, as well as the media, portrayed the conflict as one that only involved white servicemen and women. Regrettably, this has continued to be the case, even after the West Indian Ex-Servicemen and Women’s Association was founded in Britain in the 1970s. Since then the organisation has made great efforts to raise awareness of their contributions to the war (see Appendix I). Regarding the RAF, while black flyers were a minority among aircrew, they did make an important contribution to the British war effort, as this book will show. Exact figures have been difficult to establish, but in a memorandum prepared for the Air Ministry in 1945, an estimate of around 422 ‘coloured’ (the blanket term then used to include West Indian, West African, and South Asian flyers) had served as aircrew during the war, with a further 3,900 acting as ground crew (see Statistics).3

When Britain declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939, the colonies rallied to support the war effort. For some it was an opportunity to show their loyalty to the mother country. For others, especially those who volunteered for the RAF, it was a chance to leave home and have an adventure. For the more progressive-thinking colonials, the war was seen as a route to post-war decolonisation and independence. Ben Bousquet, co-author of West Indian Women at War, said: ‘Before the war, in all of the islands of the Caribbean, people were agitating for freedom. With the advent of war they put aside their protestations, they put aside their battles with the British government, and went to sign on to fight.’

In BBC Radio 2’s documentary The Forgotten Volunteers, the presenter Trevor McDonald commented:

Altogether, over three and a half million black and Asian service personnel helped to win the fight for freedom but, despite the courage and bravery they showed in volunteering to fight, once the war was over, they found that old suspicions returned. Sometimes it’s so easy to forget. To all the men and women from the West Indies, Africa and the Indian subcontinent, who volunteered to fight in the first and second world wars, we owe a debt of gratitude and respect.4

In 1974 BBC television screened a ground-breaking historical series called The Black Man in Britain, 1550–1950. It was the first British television programme to acknowledge that there had been a black community in Britain for over 400 years. One episode, ‘Soldiers of the Crown’, was the first to recognise the contribution made by West Indian servicemen to the Second World War. Two interviewees stood out, and they summarised the situation West Indians found themselves in after the declaration of war in 1939. They were Ivor Cummings, who had been the assistant welfare officer for the Colonial Office, and Dudley Thompson, a Jamaican who had served as a flight lieutenant in the RAF from 1941–45 and with the 49 Pathfinders Squadron. He was awarded several decorations. Towards the end of the war Thompson served as a liaison officer with the Colonial Office where he assisted Jamaican ex-servicemen who wanted to settle in London.

In ‘Soldiers of the Crown’, Ivor explained why he had been denied a commission in the RAF in 1939: ‘That rule [in the King’s Regulations] excluded all of us. I couldn’t join the Royal Air Force because I was not of pure European descent. We were able to get rid of that ridiculous disqualification otherwise we should not have been able to mobilise our volunteers in the way that we did. They wouldn’t have qualified for commissions.’5 The rule referred to by Ivor was abandoned, but it was too late for Ivor who had accepted the post with the Colonial Office. He said: ‘It is not done nowadays to talk about patriotism and the mother country because the Empire does not exist. It did exist in 1939 and there was no doubt at all that there was a great feeling of attachment and affection to this country by the colonies, in Africa and particularly in the West Indies.’6

Ivor said that one of the most important things that happened to West Indians during the war was the exposure to a different type of government, one that enabled them a certain amount of freedom, a better way of life and access to a higher education:

[S]o when they returned home after the war, they returned to the same government they had left. It was autocratic and people didn’t want this. They resented this and the fact that the economic conditions in these places were absolutely appalling. For the returning servicemen and women, the officials, the governors, and others were very tiresome people indeed and didn’t know how to deal with those who had been away in the war. After the war I was sent out to the Caribbean and I visited the three major islands, including Jamaica, and I was absolutely appalled. There were no opportunities for these people. The whole thing quite horrified me and I told everyone exactly what I felt about this. It was quite clear to me that this was a watershed. This whole war experience had been a watershed, that there were going to be changes.7

For many in the colonies post-war reform was slow, but the changes they expected eventually came with independence; for example, Ghana (1957), Nigeria (1960), Jamaica (1962), Trinidad and Tobago (1962), Kenya (1963), Guyana (1966) and Barbados (1966).

In ‘Soldiers of the Crown’, Dudley Thompson described how he felt on arriving in England from Jamaica in 1940:

As a colonial I would say the effect is confusing in that Jamaica – which you would consider a model colony – always saw the whites as leaders, governors, heads of departments, executives, and so on. You grew up with it. You knew that in the police force, no matter how great you were, you could never get promotion. Those were limitations you accepted. You weren’t even militant about it. And then you come to a country where, for the first time, you see white street sweepers, white bus drivers and other more menial tasks that you never imagined white people did. It was an eye opener. Things were not as you had always expected it to be, and it was a psychologically traumatic situation and more than confusing.8

In England during the war, Dudley discovered that it was possible to meet – and make friends with – white people:

You made friends, and you got used to the English way of life. There was a certain amount of courtesy from the English which you did not experience at home and you just adjusted into the English situation which was far from unpleasant. You were accepted as a soldier at a time when soldiers were coming from all parts of the Empire. You were rather proud that you wore a different flash on your shoulder because you saw Poland, France, Australia, Jamaica identified. You were just one of the sections of people whom England was glad to receive as fighting for the general cause.9

However, racial conflict was never far away:

You’d find at dance halls there were incidents where they felt black soldiers should not be in that place and sometimes they came from people like the Rhodesian forces who were visiting as well. And you did find occasional cases of friction, so much so that towards the end of the war, liaison officers were created within the Royal Air Force to take care of these situations. I was a liaison officer and from time to time was called to various places where there were disruptions, fights, and ugly incidents that needed smoothing out.10

In Jamaica, access to education was restricted, but in wartime Britain Dudley discovered a whole new world of knowledge opened up to him:

In the colonies there was very limited reading material; most of the books that would be interesting were banned anyway. There was no university. You come to England and find you’ve got a far more liberal selection of material. You can walk into any library and pursue studies. You can pursue studies of your own country much more widely than you could at home.11

In ‘Soldiers of the Crown’, Dudley summarised the effect the war had on the colonials:

The effect on the armed forces, and the civilians who were munitions workers, was to show that, in England, while you were treated as a normal, average citizen, there were many more opportunities which were open to you there than were open to you at home. You could learn skills, at universities and technical schools, and you became proficient in those skills. Those skills were either non-existent at home or reserved for white people who were ruling you rather than for yourself. So to a great extent it tremendously increased your self-reliance. The other experience was to show that you were a foreigner and that when you went home you would have to be master in your own house. I would say it increased your sense of national feeling and for the first time you felt that you had to make your own home your own. You also met people from other parts of the Empire who felt similarly, particularly from Africa.12

The freedom that the British have enjoyed since 1945 was made possible by the support of the peoples of their former empire. These people made a major contribution to the winning of that freedom. They fought hard for it, and some even gave their lives. However, recognition for this support – and the sacrifices made – has been almost non-existent. In 1995 Britain’s Conservative government, under the leadership of Prime Minister John Major, failed to invite any East and West African and Caribbean governments to take part in the fiftieth anniversary Victory in Europe (VE) Day celebrations on 8 May. Lobbying by the Black and Asian Studies Association (BASA) prompted Bernie Grant MP to take up the issue, and Marika Sherwood explained in her passionate editorial in BASA’s Newsletter:

In what seems like something of a panic measure, the government took a partial U-turn: it invited the Jamaican and Trinidadian governments to participate. From what we understand, the other Caribbean governments were not consulted about this game of favouritism/imperialism. The information I have is that the largest number of servicemen/women who came to Britain from the Caribbean were from Jamaica, then British Guiana, Trinidad, Barbados, Bermuda. Bernie Grant declared himself to be satisfied with this outcome, but we were not. However, all further efforts met with rebuff; even our letter to the Queen as head of the Commonwealth only elicited the usual response from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office: insufficient numbers of Africans had actually fought in Europe. That the first victory over the Axis powers, the Italians in Abyssinia, which surely was the necessary precursor to the victories in Europe, had been fought partly by African troops was of no consequence. We also raised the issue of merchant seamen, up to one quarter of whom were from the colonial empire during the war: they have been completely ignored. Without the sacrifice of those men, so many of whom died, this country would have been starved both of food and of war material. So much for the grateful ex-Mother Country.13

Nine years later the historian Ray Costello offered an explanation for this omission when he was interviewed by the reporter Danielle Weekes in The Voice newspaper. He said that Britain had been reluctant to show the world that black servicemen and women from Britain and the colonies had played a part in freeing the oppressed ‘because they were afraid that it would feed the desire for independence’:

If black people are shown to have the capacity for bravery it makes them human, heroes even. And heroes should have freedom and independence. Britain did not want that. It was more difficult to conceal our contributions at the end of World War II because of the sheer numbers who fought. The omission of the contribution of blacks to the British armed services is a crime comparable to slavery.14

Notes

1 Ken Follett, Hornet Flight (Macmillan, 2002), p. 9.

2 Sources: David Brewster, Trinidad Express, 25 January 2004; www.ken-follett.com.

3 NA AIR 2/6876, ‘Coloured RAF Personnel: Report on Progress and Suitability’, n.d. [Feb 1945]. See also AIR 2/6876, ‘List of Colonial Aircrew’, n.d.

4The Forgotten Volunteers, BBC Radio 2, 11 November 2000.

5 ‘Soldiers of the Crown’, The Black Man in Britain, 1550–1950, BBC2, 6 December 1974.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 For more information about Ivor Cummings, see Stephen Bourne, Mother Country: Britain’s Black Community on the Home Front, 1939–45 (The History Press, 2010); and for more information about Dudley Thompson, see Dudley Thompson, From Kingston to Kenya: The Making of a Pan-Africanist Lawyer (The Majority Press, 1993). Thompson died at the age of 95 in New York City on 20 January 2012.

13 Marika Sherwood, Black and Asian Studies Association Newsletter, No. 12, April 1995, p. 3.

14 Ray Costello (interviewed by Danielle Weekes) in ‘War of Words (60 years after D-Day, history must be rewritten to include tales of black servicemen)’, The Voice, 31 May 2004, pp. 12–13.