Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

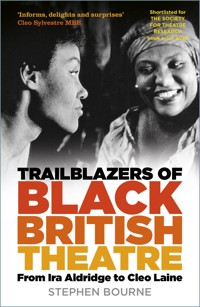

In Trailblazers of Black British Theatre, Stephen Bourne celebrates the pioneers of Black British theatre, beginning in 1825, when Ira Aldridge made history as the first Black actor to play Shakespeare's Othello in the United Kingdom, and ending in 1975 with the success of Britain's first Black-led theatre company. In addition to providing a long-overdue critique of Laurence Olivier's Othello, too-often cited as the zenith of the role, Bourne has unearthed the forgotten story of Paul Molyneaux, a Shakespearean actor of the Victorian era. The twentieth-century trailblazers include Paul Robeson, Florence Mills, Elisabeth Welch, Buddy Bradley, Gordon Heath, Edric Connor and Pearl Connor-Mogotsi, all of them active in Great Britain, though some first found fame in the United States or the Caribbean. Then there are the groundbreaking works of playwrights Barry Reckord and Errol John at the Royal Court; the first Black drama school students; pioneering theatre companies; and three influential dramatists of the 1970s: Mustapha Matura, Michael Abbensetts and Alfred Fagon. Drawing on original research and interviews with leading lights, Trailblazers of Black British Theatre is a powerful study of theatre's Black trailblazers and their profound influence on British culture today.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 388

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Trailblazers of Black British Theatre

‘An incredible starting point for any student or practitioner interested in exploring this area in more detail … I particularly enjoyed the blending of the first-person narrative with the rigor of academic research, making this both an enjoyable and educational read.’

Erin Lee, Judge, 2022 Society for Theatre Research Book Prize

‘Stephen Bourne is my go-to for the stories of Black British people that would otherwise be forgotten. [This book] is a history of trailblazing Black theatre-makers, exceptionally researched and brimming with detailed knowledge. It is also a love story and a tribute to the Black creatives that have shaped not only theatrical history but the way future generations view the world.’

Patrice Lawrence MBE, FRSL, author of Orangeboy

‘I’m amazed by Stephen’s extensive knowledge of the long history of Black theatre in Britain. This is an invaluable resource for anyone interested in Black British history, both on and off the stage.’

Kandace Chimbiri, author of The Story of the Windrush and The Story of Afro Hair

‘Every young Black actor should read this book in recognition of the legacy of Black actors in the UK. Within it they will find inspiration, a sense of belonging and an understanding of the limitless possibilities that await them in the world of acting.’

Suzann McLean MBE, CEO/Artistic Director Theatre Peckham

Also by Stephen Bourne

Aunt Esther’s Story (ECOHP, 1991)

Black in the British Frame: The Black Experience in British Film and Television (Cassell/Continuum, 2001)

Black Poppies: Britain’s Black Community and the Great War (The History Press, 2014; 2nd edition 2019)

Brief Encounters: Lesbians and Gays in British Cinema 1930–1971 (Cassell, 1996)

Elisabeth Welch: Soft Lights and Sweet Music (Scarecrow Press, 2005)

Esther Bruce: A Black London Seamstress (History and Social Action Publications, 2012)

Evelyn Dove: Britain’s Black Cabaret Queen (Jacaranda Books, 2016)

Fighting Proud: The Untold Story of the Gay Men Who Served in Two World Wars (I.B. Taurus, 2017)

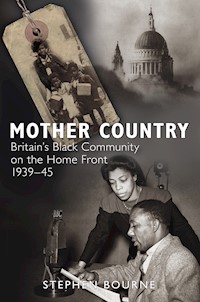

Mother Country: Britain’s Black Community on the Home Front 1939–1945 (The History Press, 2010)

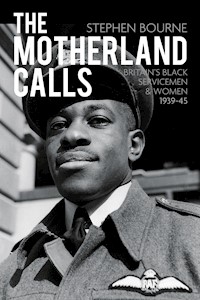

The Motherland Calls: Britain’s Black Servicemen and Women 1939–1945 (The History Press, 2012)

Playing Gay in the Golden Age of British Television (The History Press, 2019)

Under Fire: Black Britain in Wartime 1939–1945 (The History Press, 2020)

War to Windrush: Black Women in Britain 1939–1948 (Jacaranda Books, 2018)

Cover illustration: Cleo Laine and Pearl Prescod. (Author’s collection, courtesy of Pearl Connor-Mogotsi)

First published as Deep Are the Roots: Trailblazers Who Changed Black British Theatre in 2021

This paperback edition first published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Stephen Bourne, 2021, 2025

The right of Stephen Bourne, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75099 910 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Author’s Note

Preface

Introduction: ‘The Women on Whose Shoulders We Now Stand’

Part 1: Beginnings

1 Sonia

2 Laughing at Larry

3 Cleo and Tommy

Part 2: The First Trailblazers

4 Ira Aldridge

5 Paul Molyneaux: The Forgotten Othello

6 Victorian and Edwardian Music Halls

7 Sentimental Journey

8 Paul Robeson: Magical Fires

9 Una Marson: London Calling

10 Florence Mills: Beautiful Eyes and a Joyful Smile

11 Elisabeth Welch: A Marvellous Party

12 Buddy Bradley and Berto Pasuka: On with the Dance

Part 3: A New Era

13 Enter, Stage Left: The First Black Drama Students

14 Ida Shepley: A Gentle, Friendly Star

15 A New Feeling: Britain’s First Black Theatre Companies

16 Gordon Heath: A Very Unusual Othello

17 Edric Connor and Pearl Connor-Mogotsi: Against the Odds

18 Surviving and Thriving: Later Black Theatre Companies

19 Barry Reckord, Errol John and the Royal Court

20 Cleo Laine: Shakespeare and All That Jazz

21 Three Playwrights: Mustapha Matura, Michael Abbensetts and Alfred Fagon

Postscript: Norman Beaton

Appendix: Database of Stage Productions from 1825 to 1975

Notes

Further Reading

About the Author

Author’s Note

Thanks go to David Hankin for digitally remastering some of the photographs; Keith Howes for his constructive comments on an early draft of the book; and Simon Wright, my editor at The History Press, who in the summer of 2020 asked me if I had an idea for a new book. This is the result.

I would like to recommend two online resources for further research: the University of Warwick’s British Black and Asian Shakespeare Performance Database (bbashakespeare.warwick.ac.uk) and the National Theatre’s Black Plays Archive (www.blackplaysarchive.org.uk).

In Trailblazers of Black British Theatre, the terms ‘Black’ and ‘African Caribbean’ refer to African, Caribbean and British people of African heritage. Other terms, such as ‘West Indian’, ‘Negro’ and ‘coloured’ are used in their historical contexts, usually before the 1960s and 1970s, the decades in which the term ‘Black’ came into popular use.

Though every care has been taken to trace or contact all copyright holders, I would be pleased to rectify at the earliest opportunity any errors or omissions brought to my attention.

Preface

Trailblazers of Black British Theatre evolved from the time I was invited by the Theatre Museum in London’s Covent Garden to loan items from my collection to its Let Paul Robeson Sing! exhibition in 2001. Little did I realise that it would lead to me cataloguing its Black theatre collection. I drew the museum’s attention to the fact that its vast archive included programmes, press cuttings, photographs, books and other material relating to Black theatre in Britain from as early as 1825, but that researchers who visited the museum’s study room were not aware of the richness of what existed.

Funded by a small research grant from The Society for Theatre Research, I began by surveying the early years of Black British theatre from the 1820s to the 1970s under the supervision of Susan Croft, who was the museum’s curator of contemporary performance. The stage careers of African American actors such as Ira Aldridge and Paul Robeson had already been well documented, and so it was not difficult to find material relating to them. It was fascinating to uncover the forgotten work of Black actors and writers from Africa, Britain and the Caribbean. Susan then put together the Theatre Museum’s publication Black and Asian Performance at the Theatre Museum: A User’s Guide, published in 2003, which included a database I had compiled of landmark Black British theatre productions from 1825 to 1975, while Dr Alda Terracciano compiled a similar database covering the period from 1975 to 2000.

Later on, I applied for and received a Wingate Scholarship in 2011 to further my research into early Black theatre in Britain. In 2012 I was interviewed for the documentary Margins to Mainstream: The Story of Black Theatre in Britain, and in July 2013 I participated in Warwick University’s Shakespeare symposium with the presentation Beyond Paul Robeson … Black British Actors and Shakespeare 1930–1965.

And yet publishers repeatedly rejected my proposal for a book on the subject. ‘Your book is too niche,’ one of them said. Another told me that ‘Black people do not buy books, so there is no market for them.’ There was one exception: a young and enthusiastic editor did show an interest and he was keen to commission the book, but he was overruled by his editorial advisory board. Disheartened, I gave up and put the proposal away.

The landscape changed dramatically in 2020 with the Black Lives Matter movement, which drew attention to the Black presence in Britain both historically and in contemporary life. Almost immediately two of the publishers who had rejected my proposal contacted me and asked me if I had any ideas for Black history books, but they were too late. I had just been contacted by Simon Wright, my editor at The History Press, and I had sent him the proposal for this book. A contract was immediately negotiated. However, I decided to write Trailblazers of Black British Theatre in a different way to my previous books.

When I started out as a professional writer, I was always told to write objectively, not in the first person. I had never been encouraged to personalise my books. That is the academic way of writing history books; but with Trailblazers of Black British Theatre, it was not going to be my way. For years I had enjoyed personal connections and friendships with many of the people I wanted to include in the book, so I wanted to avoid distancing myself from them by being ‘objective’. This is why the reader will find Trailblazers of Black British Theatre a personal history and not an objective, academic one.

It is the personal relationships and anecdotes that are missing from so many books I have read on this subject – not that there have been very many. Two of my favourite academic works on the subject are Errol Hill’s Shakespeare in Sable: A History of Black Shakespearean Actors (1984) and The Cambridge Guide to African and Caribbean Theatre (1994), co-edited by Hill. Colin Chambers’s Black and Asian Theatre in Britain: A History (2011) is also recommended.

There have been several excellent autobiographies, including Norman Beaton’s Beaton But Unbowed (1986), Gordon Heath’s Deep Are the Roots: Memoirs of a Black Expatriate (1992), Yvonne Brewster’s The Undertaker’s Daughter: The Colourful Life of a Theatre Director (2004), Edric Connor’s Horizons: The Life and Times of Edric Connor (published posthumously in 2007), Cy Grant’s Blackness and the Dreaming Soul (2007) and Corinne Skinner-Carter’s Why Not Me? (2011). I wish there had been more.

Trailblazers of Black British Theatre is not intended to be the definitive book on the subject. However, I have attempted to draw together the stories of some of the many personalities who created magic in British theatre from the 1820s to the 1970s, and to give them some context. I have also added many titles to my original 2003 database, in the hope that it will inspire others to embrace the breadth of the subject and undertake further research.

Carmen Munroe in James Baldwin’s The Amen Corner, autographed at the Lyric Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue, in 1987. (Author’s collection)

Introduction

‘The Women on Whose Shoulders We Now Stand’

On 2 December 2017 I had the pleasure of taking part in Palimpsest Symposium: A Celebration of Black Women in Theatre at the National Theatre. It was the actress Martina Laird who invited me to take part and celebrate the work of those she described as ‘the women on whose shoulders we now stand’. I said I would be happy to start the event (which included two panel discussions) with an illustrated talk about early appearances of Black actresses in British theatre. I gave it the title ‘Black Women in British Theatre: The Beginnings 1750s to 1950s’ and I began by acknowledging the actress who had played Shakespeare’s Juliet in Lancashire in the late 1700s. The attendees included many Black women who were drama students, actresses, playwrights and directors. I wasn’t sure how many of them would have heard about the actresses I discussed. There is very little accessible information about the early years of Black British theatre and so the lives and achievements of many of these women have been lost to time.

The actress who played Juliet in the 1790s remains unidentified, but the reference to her ethnicity is clear. When John Jackson published The History of the Scottish Stage in 1793, he noted the following:

I had accidently seen the lady, as I was passing through Lancashire, in the part of Polly [in John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera]. I could not help observing to my friend in the pit, when Macheath addressed her with ‘Pretty Polly’, that it would have been more germain to the matter, had he changed the phrase to ‘SOOTY Polly.’ I was informed, that a few nights before, she had enacted Juliet.1

Having begun my talk with this unidentified actress, I closed with Cleo Laine’s dramatic debut in Flesh to a Tiger at the Royal Court in 1958. I also spoke about Emma Williams, the West African who acted in George Bernard Shaw’s Back to Methuselah in the 1920s, sharing the stage of the Royal Court Theatre with Edith Evans and a young Laurence Olivier. After 1931, Emma vanishes, but other Black British actresses surface in the 1940s, including Ida Shepley and Pauline Henriques. I hoped that the talk would draw attention to the lives of these extraordinary women.

Afterwards, I took part in a panel discussion hosted by Martina Laird and Natasha Bonnelame, Archive Associate at the National Theatre. The panellists also included Yvonne Brewster and Angela Wynter. It was an enjoyable and inspiring morning session. In the afternoon, Martina and Natasha hosted another panel discussion, this time bringing Yvonne and Angela back together alongside the actresses Anni Domingo, Noma Dumezweni and Suzette Llewellyn.

In the 1980s and 1990s I had the pleasure of befriending some of the women who are featured in this book. They include Elisabeth Welch, Pauline Henriques, Carmen Munroe, Cleo Sylvestre, Pearl Connor-Mogotsi, Nadia Cattouse, Isabelle Lucas, Joan Hooley, Corinne Skinner-Carter and Anni Domingo. Over a long period of time, these personal friendships have given me insights into the work of Black women whose lives intertwined with many aspects of Black British theatre. They have trusted me with their stories and, in some cases, shared their memorabilia. It has been a wonderful experience.

Emma Williams as Doll in And So to Bed at the Queen’s Theatre, 1926. (Author’s collection)

Sadly, I have never met the brilliant Mona Hammond. Somehow, I missed her. However, in 1989, I did see her wonderful performance as Lady Bracknell, directed by Yvonne Brewster, in the Black-cast version of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest. Shortly afterwards, when I was interviewed on BBC Radio, I met the actor Paul Barber at BBC Broadcasting House and we talked about Hammond. He told me that she is ‘our Judi Dench’. Hammond had come to Britain from Jamaica in 1959 with a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. It was her dream to play Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth, but such a plum role was unavailable to Hammond at the start of her career. However, in 1972, when she played her first leading role in the theatre at the Roundhouse Theatre, she was cast as the Wife of Mbeth (Lady Macbeth) in Peter Coe’s innovative version of the Shakespeare tragedy. Set in Africa, it was called The Black Macbeth and co-starred Oscar James as Mbeth. On 24 February 1972, Irving Wardle of The Times noted Hammond’s ‘reading of true passion and originality whose stone-faced exhaustion after the banquet and sleep-walk scene are as good as any I have seen’. In her biography for the programme, Hammond called the role ‘a dream come true’. In the early 1970s, she followed her appearance in The Black Macbeth with parts in Mustapha Matura’s As Time Goes By, Michael Abbensetts’s Sweet Talk and Alfred Fagon’s 11 Josephine House and The Death of a Black Man. In 2005, Hammond received an OBE for her services to drama.

In 1987 I met Carmen Munroe for the first time when I interviewed her for the magazine Plays and Players in her dressing room at the Lyric Theatre in Shaftesbury Avenue. Munroe was taking it easy between the matinee and evening performances of James Baldwin’s The Amen Corner, in which she played – brilliantly – the leading role of Sister Margaret. Carmen told me that her first professional appearance had been as a maid in Tennessee Williams’s Period of Adjustment at the Royal Court in 1962, ‘but I never played a maid again. I figured once you have played a maid, there didn’t seem much point in playing another.’

Eventually some good theatre work came her way, including Alun Owen’s There’ll Be Some Changes Made (1969): ‘I thought “Gosh, this is the opening that I’ve been dying for.” We had wonderful reviews and I thought, “I hope this continues.”’ And it did, with a revival of Jean Genet’s The Blacks (1970) at the Roundhouse: ‘This gave Black actors and actresses a great opportunity to get together and really put on what turned out to be a wonderful production.’ Then came George Bernard Shaw’s The Apple Cart (1970) at the Mermaid. ‘Following in Dame Edith Evans’s footsteps,’ wrote one reviewer. ‘Why doesn’t someone write something for this girl?’ wrote B.A. Young in the Financial Times.

For Carmen, these years were particularly rewarding. But, in 1971, the work suddenly stopped: ‘I did a lot of work. Mainly because directors wanted to use me. Then it changed. Suddenly Black artists became a “threat” to the establishment.’ Carmen believes that Enoch Powell’s inflammatory ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech in 1968 was partly responsible for this. In 1973, she seriously considered giving up her acting career: ‘For almost a year I spent a depressing time believing that I was not going to realise my potential. This is a hard thing to take. But I hung on.’

Programme cover for The Black Macbeth at the Wyvern Theatre in Swindon, 1972. (Author’s collection)

In 1985, she played Lena Younger in Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, directed by Yvonne Brewster, at the Tricycle Theatre. And when The Amen Corner came along, she told me she found it:

Amazing to be in a cast where people are doing something wonderful. It is fulfilling to be part of this. To experience this. I’ve been in the business a quarter of a century and I’m aiming to partake in the next quarter of a century too, and hope there will be more work like The Amen Corner.

There was, and Carmen continued to win critical acclaim for her leading roles in such plays as Alice Childress’s Trouble in Mind at the Tricycle in 1992.

I met Isabelle Lucas in 1989 at her beautiful home in Kingston upon Thames. Isabelle had arrived here from Canada in 1954 with dreams of a career as an opera singer, but Covent Garden and Sadler’s Wells turned her away. Penniless and desperate for work, Isabelle answered an advert in The Stage newspaper and successfully auditioned for The Jazz Train (1955), a Black-cast revue at the Piccadilly Theatre: ‘I sang “Dat’s Love” from Carmen Jones so my ambition to sing opera on the London stage was fulfilled, but not at Covent Garden!’

Isabelle then alternated between musicals and drama. Her stage work in the 1960s included Ex-Africa at the 1963 Edinburgh Festival, described as ‘a Black odyssey in jazz, rhyme and calypso’; Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle (1964), a Glasgow Citizens’ production in which she was the first woman to play the Storyteller; the Negro Theatre Workshop’s Bethlehem Blues (1964); and as Barbra Streisand’s maid in the 1966 London production of the Broadway hit Funny Girl.

In 1968, two years after the release of the Oscar-winning film starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, Isabelle and Thomas Baptiste were cast as the first Black Martha and George in Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? at the Connaught Theatre in Worthing. This was inspired casting, and it took a British production to make this breakthrough with a recent American stage classic. Isabelle proudly showed me photographs from this innovative production.

She then joined the National Theatre at the Old Vic in 1969 to appear in Peter Nichols’s comedy The National Health and George Bernard Shaw’s Back to Methuselah.

When Isabelle successfully auditioned for the role of Mammy in the stage musical version of Gone with the Wind (1972), she had reservations about taking the part:

It was a good role and I had the Drury Lane stage to myself for a couple of solos … But this was during the time of Black consciousness and I had doubts about wearing a bandanna and playing a mammy. Then I thought if I do it honestly it will be OK, and it was.

Isabelle concluded our interview by expressing disappointment that more had not been achieved in Britain for Black actors:

In America they have pioneered integrated casting and there is work for mostly everybody, Black and white. Here, Black actors are kept in a ghetto … I have worked in this country for nearly forty years and all we are left with is Notting Hill Carnival and a struggling Black theatre constantly under threat because of cuts in funding.

In 1993, Isabelle wrote to me to tell me how much she had enjoyed playing the Nurse in Romeo and Juliet, which Judi Dench directed at the Open Air Theatre in Regent’s Park. It was to be her final stage appearance. Ill health forced her into semi-retirement, and she passed away on 24 February 1997.

I also met Nadia Cattouse for the first time in 1989, and she offered some fascinating insights into the problems Black actors faced in the 1950s and 1960s, especially if they came to Britain from the Caribbean:

They had this fixed idea in their heads that, if you were American, you were streets better than anyone who came from the Caribbean. Our accent bothered them. They constantly told us to place our emphasis on a different syllable, and this would make us so self-conscious we could never think ourselves into a role because we were always conscious of the demand from the director, or whoever, that we speak in a different way. And so there was a kind of loss of control of the performance we would like to give. I had a lot of that. We did not want to rock the boat so usually we could use our intelligence to guide ourselves through, without upsetting the status quo, because time costs money in this business and we had to remember that too.

In 1991, Joan Hooley told me how the Royal Court Theatre was instrumental in helping to build the careers of Black playwrights and actors. In 1958, Joan had been an understudy in Errol John’s Moon on a Rainbow Shawl. She was also in the cast of Jean Genet’s The Blacks. She described this as:

Great fun to do. To the best of my memory, it was the first stylised production of that type in England. It was around this time that theatres like the Royal Court started doing productions with Black casts. Well, I think there was a need for it, really, because there was so much Black talent around … Suddenly, these plays were being commissioned by people with insight into what needed to happen to the theatre. There was a general interest in seeing what Black writers had to offer, and what Black talent there was to perform these works. It was a very productive period between 1958 and 1962. I was constantly working – very little television, but a lot of theatre.

Corinne Skinner-Carter. (Author’s collection, courtesy of Corinne Skinner-Carter)

I also enjoyed meeting Corinne Skinner-Carter in 1998 when I interviewed her for the Black Film Bulletin. Corinne had come to Britain from Trinidad in 1955. She worked as a dancer and actress but she also had teaching to fall back on when acting work became scarce. After her arrival, Corinne befriended Claudia Jones, a fellow Trinidadian who, like Edric and Pearl Connor (also Trinidadians) made things happen. Corinne said:

Claudia had been persecuted in America for her political beliefs. After settling in England, she launched the West Indian Gazette in Brixton. This was Britain’s first major newspaper for Black people. In 1958, Claudia decided to pull together a group of Black people from the arts, to show everybody that we were here to stay, that there was harmony between Blacks and whites, in spite of the Notting Hill riots. So, Claudia coordinated the first West Indian Carnival in Britain with the help of Edric and Pearl Connor, Cy Grant, Pearl Prescod, Nadia Cattouse and myself. The first Carnival took place in St Pancras Town Hall, and it was packed! It was not until 1965, the year after Claudia died, that Carnival took to the streets of Notting Hill.

Corinne also gave me an overview of her life and career: ‘I have always been very selective. If I am not happy with a script, I turn it down. But I have been fortunate. On coming to England in 1955, I trained as a teacher, so I haven’t always had to rely solely on acting for my bread and butter.’

In 1998, shortly before she passed away, Pauline Henriques wrote to me about my book Black in the British Frame: The Black Experience in British Film and Television, for which I had interviewed her. Pauline congratulated me on the publication, which she found intriguing:

I find myself thrown back into a time that was a thrilling part of my young life … I can sink into the warm memories of my relationships to so many interesting Black people: Connie Smith, Edric and Pearl Connor, Errol John and Earl Cameron. I can’t thank you enough. So, Stephen, you’ll understand why I am filled with admiration for the time and effort you must have put into the book. I am also delighted at the threads of warmth throughout the text. With all good wishes to the successful author: Stephen Bourne.

A few weeks later, Nadia Cattouse also reacted positively to Black in the British Frame in a letter:

I like the way you write. You are so deeply interested, never ever patronising the way one or two others can be, and full of insights. You hit the nail on the head when you mention ‘the wall of silence that surrounds the history of our nation’s Black people.’ I have long come to the conclusion we will never be a society of real and not ‘pretend’ people … Some mean well and bless them for it. That is England.

Part 1

Beginnings

Sonia Pascal and Stephen Bourne in 1982. (Author’s collection, courtesy of Linda Bourne Hull)

1

Sonia

In 1981, when I worked at the Peckham dole office, I took benefit claims from the unemployed and processed them. This was Maggie Thatcher’s Britain and many people were out of work. Every day there were numerous claims to process. It was depressing, laborious work, but my days were brightened by a co-worker who became my best friend and soulmate.

Sonia Pascal and I immediately hit it off. We shared the frustration of the daily grind of our civil service office work. Sonia’s background was a bit of a mystery. She was born in Grenada or Jamaica – I never did find out – but she was raised in Britain. She was a free spirit, but she was also down to earth. She loved acting and writing poetry. To relieve the boredom of our ‘day jobs’, we spent many happy lunch breaks in a local pub, putting the world to rights and sharing common interests in Black arts and theatre.

We giggled about the dole office gossips who were convinced we were an ‘item’. This was not the case because I was gay. I had to keep it a secret from my colleagues because, when I joined the civil service, I signed the Official Secrets Act. In those days it included a paragraph which declared that I was not a homosexual. By signing my name to this document, I reassured the powers that be that I was not a ‘security risk’ to the United Kingdom. I told Sonia I was gay and she also kept it a secret; if senior staff at the dole office had found out, I would have risked being sacked. However, I had noticed that some of the male staff at the Peckham dole office were also ‘musical’ and, to please Mrs Thatcher, pretending to be straight. A couple of them were outrageously camp and obviously gay to members of staff who wished to acknowledge it but, as far as I can recall, no one was outed, sacked and forced to join the unemployed claimants. I was aware that gay liberation had happened in Britain in the 1970s, but it hadn’t reached the civil service.

Just after I started working in the dole office, the Brixton uprisings began. From 10 to 12 April 1981 tensions between the police and Brixton’s Black youth erupted into violence. It was inevitable that this would happen; the tensions had been building up for years.

We were living in the immediate aftermath of the tragic New Cross Fire on 18 January that year, in which thirteen Black British youths, all aged between 15 and 20, had lost their lives. People became angry and frustrated when they felt that the police were not taking seriously the investigation of the cause of the fire, which some suspected was racially motivated.

Consequently, the Black People’s Day of Action was organised by activist John La Rose and others for 2 March 1981. With over 20,000 attendees, it was the largest demonstration of Black people and their allies in Britain to date. Sonia and I participated in the march. It started in New Cross and via Elephant and Castle it continued across Blackfriars Bridge. Here the police attempted to stop marchers going to Fleet Street, fearing there would be trouble in that area of London where right-wing journalists were based. The press had done much to fuel racism and negative media images of Britain’s Black community. In spite of this interruption, and a confrontation with the police, the marchers eventually reached Hyde Park.

In 1981 Black youths felt alienated and victimised by the police. Margaret Thatcher and her Conservative government didn’t help matters; their hostile language about the country being ‘swamped’ by immigrants inflamed the situation. The police used their repressive ‘sus’ (suspected person) stop-and-search law to openly bully and harass young Black men.

In south London our local police stations – Peckham, Brixton and Carter Street off Walworth Road – had terrible reputations in general. It was common knowledge that villains from all walks of life begged their arresting officers to take them anywhere except the cells at Brixton or Carter Street. As a kid growing up in the area, if we saw a policeman approaching us, we didn’t stop and ask him the time. We ran for it.

By the early 1980s, Brixton was overrun by police officers who stopped and searched anything that moved. In 1980 my own fear and mistrust of the police was confirmed when I was stopped and searched by two officers opposite the council flat on Peckham Road where I lived with my parents. So I wasn’t surprised when Black youths vented their anger and frustration with the authorities. They took to the streets and fought back. Other parts of the country followed, such as St Pauls (Bristol), Toxteth (Liverpool) and Handsworth (Birmingham).

Brixton became a ‘no-go’ area. Many shops and buildings were burnt out. The uprising spilled over into Peckham and we were in the thick of it. In Rye Lane, business owners were advised to close early and board up their windows. The dole office, situated off Rye Lane in Blenheim Grove, was advised to do the same. In the middle of the afternoon, I walked home, shocked by the sight of the boarded-up shop windows. For just one afternoon and evening, Peckham became a ghost town. The silence was eerie. Fortunately, the violence that Brixton had witnessed over several days and nights was not repeated in Peckham. However, from our living room window, we witnessed a number of police officers chasing Black youths along Peckham Road or up Talfourd Road, which was directly opposite us.

Maggie Thatcher and the police made sure that the uprising was suppressed and eventually the tensions subsided. Commenting on Charles and Diana’s marriage, which took place that July, Ray Gosling said wryly in New Society (1 December 1983): ‘Oh happy day when Lady Diana became a Princess – because the riots were turned off like a tap by the royal wedding.’

Meanwhile, the unemployed continued to flood into our office to make claims, keeping Sonia and me extremely busy and stressed, though we still found time to share our interests.

Sonia’s love of acting took her to the L’Ouverture Theatre Company, one of whose aims was to encourage young Black people into the world of theatre. In 1981, in her spare time, Sonia rehearsed their production of Antigone by Sophocles. It was translated by John Lavery and directed by the Jamaican-born theatre trailblazer Yvonne Brewster. At the dole office, Sonia described Yvonne to me as an inspiring director. The production was staged at Lambeth Town Hall from 19 to 22 October 1981.

In the programme I have kept all these years, Sonia is listed among the cast as ‘Speaking Chorus’. I remember seeing her on stage and feeling proud that my friend and colleague was pursuing her dream. She was such an inspiration to me. In the programme her short biography reads: ‘Searching for an identity may be an inappropriate starting point for some but Sonia feels this is paramount in her life. Excitement and a profound interest in people may be found in her satirical poetry. Her motto about life: Make it spicy!’

In 1981 Sonia took me to Peckham Odeon on the high street to see a double bill of Jamaican films then making the rounds. They were the classic reggae crime film The Harder They Come, starring Jimmy Cliff, and a hilarious comedy by Trevor Rhone called Smile Orange. Both of them had been made in the 1970s. Black youths packed into the Odeon to see Jimmy as a reggae singer forced into a life of crime, and then they screamed with laughter throughout Smile Orange. Unlike me, they understood the Jamaican patois and didn’t need to read the subtitles. With the rise in unemployment, Peckham Odeon was demolished in 1983 to make way for a brand-new job centre.

L’Ouverture Theatre Company’s Antigone at Lambeth Town Hall in Brixton, 1981. (Author’s collection)

The year 1982 was a landmark for me in terms of my developing interest in contemporary Black arts and culture. In February, Sonia and I went to the Festival of Black Independent Film Makers at the Commonwealth Institute in Kensington High Street. One of the Festival’s highlights was Menelik Shabazz’s acclaimed film Burning an Illusion. Its leading actor, Cassie McFarlane, gave a stunning performance as a young woman who becomes politicised in contemporary Britain. In her review of that evening’s screening of the film, which was received with tremendous enthusiasm by a predominantly young Black audience, Isabel Appio commented in the Caribbean Times (26 February 1982):

The most overwhelming audience turnout was for Burning an Illusion which had eager viewers spilling into the aisles. Females reacted openly: cheering Pat (Cassie McFarlane), through her journey as she confronts her troublesome boyfriend and discovers a more rewarding political identity. It was proved that night that there is a vast and receptive audience who at the moment is starved of films dealing with subjects with which they can identify.

In April, Sonia and I attended the first International Book Fair of Radical Black and Third World Books at Islington Town Hall. This had been founded by John La Rose and Jessica Huntley. In May, Sonia’s love of poetry took us to the National Theatre in London’s South Bank to see Beyond the Blues. This was a Jamaica National Theatre Trust presentation featuring the actor Lloyd Reckord reading poems from the Caribbean, USA and Africa. Poets represented included Louise Bennett, Evan Jones and Claude McKay. Some years later I befriended Lloyd and interviewed him about his acting career. In August, Sonia and I went to Notting Hill Carnival.

Black arts and culture were all around us to seek and find, but now and again Sonia and I went what we called ‘up west’ to London’s West End in order to see a ‘mainstream’ film that appealed to us. As we sobbed through the tragic, emotionally charged climax of Terms of Endearment, when Shirley MacLaine faces the tragic death of her beloved daughter, we understood why she had won the Best Actress Oscar. We thought Barbra Streisand’s Yentl was wonderful and failed to understand why some critics were harsh about her. Streisand wasn’t even nominated for an Oscar, which we thought was a terrible oversight.

Sonia encouraged me to write poems, and one of them, ‘Shadow’, about the 1981 Brixton uprising, was published in a collection called Dance to a Different Drum (1983). The poems were selected by the celebrated Jamaican poet James Berry and published by the Brixton Festival. Other poets in the collection included the legendary Linton Kwesi Johnson and the playwright Alfred Fagon. Then Sonia introduced me to the playwright and director Don Kinch.

Don had come to London from Barbados in the 1960s and established the performing company Staunch Poets and Players in 1979. When Don planned to launch and edit a new Black monthly magazine called Staunch, Sonia gently encouraged me to offer my services as a feature writer, and so I began to contribute to the magazine. One of my first commissions, published in February 1983, was an interview with the actress Cassie McFarlane, on which I collaborated with Sonia.

Sonia also introduced me to the world of contemporary Black theatre. Immediately after the 1981 uprisings, the Greater London Council (GLC) began to fund some Black theatre companies. I remember Sonia taking me to the Albany Empire in Deptford in 1982 to see the Black Theatre Co-operative’s presentation of Yemi Ajibade’s Fingers Only. It was directed by Mustapha Matura, who had been a leading light in Britain’s Black theatre movement since the 1970s.

In The Struggle for Black Arts in Britain, Kwesi Owusu described 1983 as a ‘boom year’ for Black theatre.1 That year Sonia and I went to see some of the plays in the Black Theatre Season at the Arts Theatre in London’s West End. They included Steve Carter’s Nevis Mountain Dew, Trevor Rhone’s Two Can Play, Michael Abbensetts’s The Outlaw and Paulette Randall’s Fishing, directed by Yvonne Brewster. In the ‘boom year’ we also went to see Cassie McFarlane in the stage version of Smile Orange at the Tricycle Theatre in Kilburn. The Ghana-born writer Kwesi Owusu commented, ‘The use of Jamaican Creole was an unapologetic cultural statement to the play’s British audiences. Not surprisingly, the play was perniciously attacked by some white media critics.’2 McFarlane then played the lead in Don Kinch’s play The Balm Yard, which toured many community theatres up and down the country. Sonia and I saw this production at a popular local fringe theatre, the Albany in Deptford.

In November 1983 we went to see the Theatre of Black Women at the Oval House Theatre, opposite the council flat where Sonia lived. One member of the company was Bernardine Evaristo, who went on to become a celebrated poet, novelist and Booker Prize winner. I still have the flyer with her photo on the cover.

I noticed that these productions brought together different generations of Black actors. Some came from African and Caribbean backgrounds; others were born in Britain. Some had been working here since the 1950s and 1960s, including Nadia Cattouse, Mona Hammond, Isabelle Lucas, T-Bone Wilson, Allister Bain, Corinne Skinner-Carter and Ena Cabayo; others were new faces such as Cassie McFarlane, Christopher Asante, Chris Tummings, Shope Shodeinde, Judith Jacob and Malcolm Frederick.

The February 1983 issue of Staunch included a long and detailed special report by Shirley Skerritt, the magazine’s features editor, on Black theatre in Britain. She asked, ‘Is there a Black renaissance?’ and described the new Black theatre as ‘community theatre’:

At a time when white establishment theatre is in decline … Black theatre is alive and well in community centres throughout London. Plays reflecting the Black experience are now being developed and presented by performers who are more concerned with the integrity of their material than in being stars. Playwrights like Edgar White, Don Kinch and Caryl Phillips to name but a few, are spearheading a movement which looks for its inspiration deep into the history and life-affirming struggles of the Black community. These writers have produced material which centres around Blacks themselves, with the involvement of the white world relegated to the fringes of Black life where it rightly belongs. They have transferred the preoccupation with actions which take place on the periphery, to a new focus on issues at the very heart of the Black experience.

Skerritt then explained how this ‘uncoiled energy’ boomeranged on James Fenton, the Oxford-educated white drama critic of The Sunday Times when, in November 1982, he ‘presumptuously took the platform at the Battersea Arts Centre to discuss the future of Black theatre’. Skerritt described Fenton as ‘still living in the colonial past’:

What was never understood by the colonialists was that art was never colonised – that the artist was never a slave … Black artistes have always been starved of resources, especially when they have adopted a Western philosophy towards art. Art must serve the interests of the people by whom and for whom it is created. The true critics of Black art are the Black masses who inspire it and who alone can judge its integrity.

Sonia and I remained friends forever. She eventually left the Peckham dole office to join a radio journalism course at the London College of Printing. From there she worked for BBC Radio London on the weekly magazine series Black Londoners, launched and presented by Alex Pascall in 1974. Sonia encouraged me to join a postgraduate course in journalism at the same college. It changed my life. There were times when our paths didn’t cross, but we stayed in touch via Christmas cards and Sonia always remembered to send me postcards from her travels abroad. I have kept them all. In 2004 we spoke on the phone and she told me how excited she was about a landscape gardening course she was doing. A few months later she suffered a heart attack and passed away at the age of 45. Her passing was a shock to everyone who knew and loved her. She was always full of life and was a spiritual person. She never had a bad word to say about anyone. Sonia had gently given me the confidence to begin my career as a historian of Black Britain and to reach for the moon and the stars. I miss her and I will never forget her.

Jet magazine was critical of Laurence Olivier’s portrayal of Othello: ‘It is difficult to imagine a more vulgar, inept and, far more serious, racist interpretation of the role, denoting an almost complete lack of respect for black people on the part of Olivier.’ (Author’s collection)

2

Laughing at Larry

Critics said that Othello should be played by Laurence Olivier. I don’t think it had anything to do with the standard of performance but it is one of the major parts in Shakespeare, and in the eyes of the critics the last great person to play Othello was Laurence Olivier. They measure all performances on that instead of taking it on an individual basis.

Rudolph Walker1

I was first asked to play Othello when I was fourteen, and still at school [in 1969 at Dean Close School in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire] …Of course, I was not old enough, or experienced enough; nor, as it turned out, was I Black enough … Accordingly, the make-up supervisor, the wife of the physics teacher, ruled that I should be ‘blacked up’, literally. But when I kissed Desdemona, the blackness rubbed off on her, and so this particular convention was short-lived. However, even without the aid of the black face, I attained a peak of grotesque absurdity with a faithful imitation of the accent Laurence Olivier used when he played Othello. As I recall, I was highly commended in school assembly. It was the theatrical equivalent of a Black man telling Rastus jokes. But, at the time, I was concerned to demonstrate how well I had assimilated the English theatrical tradition, and its conventions. Such naked idiocy is rare today; but my encounter with the physics teacher’s wife sowed a seed of doubt about some of the conventions and tastes of the classical theatre.

Hugh Quarshie2

My friend Sonia and I shared many things, including our sense of humour. When we were together, we always found something to laugh at. However, there was one afternoon in May 1983 when our laughter almost caused us to be thrown out of the National Film Theatre. We attended a screening of the 1965 film version of Laurence Olivier’s National Theatre stage triumph Othello. As soon as Olivier appeared on screen we gasped and burst out laughing. We couldn’t help ourselves. Having recently attended performances of several extraordinary and innovative Black theatre productions, we were left gasping for air at Lord Olivier’s outrageous posturing in blackface. He even rolled his eyes while gently stroking the face of Iago (Frank Finlay) with a rose. I whispered to Sonia, ‘When is he going to strum on a banjo and sing “oh, de doo-da day”?’ She responded with more laughter. Later on, when Othello’s jealousy turned into rage, Sonia and I were horrified at the way he distorted his blackened face and waved the palms of his hands in the air before crossing his eyes and falling to the floor. We burst out laughing again, but we didn’t laugh because we thought he was funny. We laughed because this spectacle of ‘great acting’ was embarrassing and we were bemused at this insulting, furious betrayal.