Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

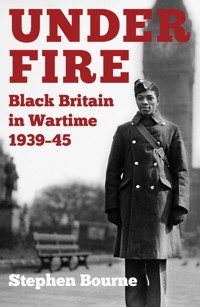

During the Second World War all British citizens were called upon to do their part for their country. Despite facing the discriminatory 'colour bar', many black civilians were determined to contribute to the war effort where they could, volunteering as air-raid wardens, fire-fighters, stretcher-bearers and first-aiders. Meanwhile, black servicemen and women, many of them volunteers from places as far away as Trinidad, Jamaica, Guyana and Nigeria, risked their lives fighting for the Mother Country in the air, at sea and on land. In Under Fire, Stephen Bourne draws on first-hand testimonies to tell the whole story of Britain's black community during the Second World War, shedding light on a wealth of experiences from evacuees to entertainers, government officials, prisoners of war and community leaders. Among those remembered are men and women whose stories have only recently come to light, making Under Fire the definitive account of the bravery and sacrifices of black Britons in wartime.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 322

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Cover illustration: Jellicoe Scoon recently arrived in England as an RAF recruit in Parliament Square, 26 March 1942. (Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, CH 5213)

First published 2020

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Stephen Bourne, 2020

The right of Stephen Bourne to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9583 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Acknowledgements

Author’s Note

Introduction

1939 Register of England and Wales

1 3 September 1939

2 The Colour Bar

3 Dr Harold Moody

4 Conscientious Objector

5 Evacuees

6 The Call of the Sea

7 The London Blitz

8 Liverpool, Cardiff, Manchester and Plymouth

9 Keeping the Home Fires Burning

10 Ivor Cummings

11 Learie Constantine

12 The BBC

13 Una Marson

14 Royal Air Force

15 Prisoners of War

16 Lilian and Ramsay Bader

17 Auxiliary Territorial Service

18 ‘They’ll Bleed and Suffer and Die’: African American GIs in Britain

19 ‘A Shameful Business’: The Case of George Roberts

20 Flying Bombs

21 Front-Line Films

22 Mother Country

23 VE Day

24 If Hitler Had Invaded

Appendix 1: Members of the Royal Air Force in Memoriam

Appendix 2: Interviews

Notes

Further Reading

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Keith Howes

Linda Hull

BBC Written Archives Centre

Black Cultural Archives

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Imperial War Museum (London)

National Archives

West Indian Association for Service Personnel

Author’s Note

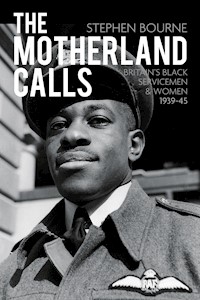

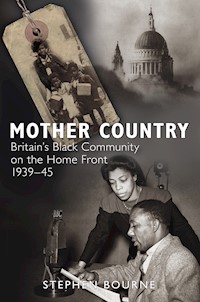

Under Fire combines some of the stories in two of my previous books: Mother Country: Britain’s Black Community on the Home Front 1939–45 (2010) and The Motherland Calls: Britain’s Black Servicemen and Women 1939–45 (2012), both published by The History Press. It also includes a wealth of new information and personal testimonies, as well as recently discovered photographs, some previously unpublished.

Unlike the previous two books, the material in Under Fire has been organised chronologically and thematically. However, the emphasis is still on first-hand testimony from the black Britons who supported the war effort. This comes from published sources and personal interviews by the author.

Over 100 black and mixed-race citizens have been identified by the author in Greater London and across the country in the 1939 Register of England and Wales. This previously unpublished information has been added to the book from www.ancestry.co.uk.

In Under Fire, the terms ‘black’ and ‘African Caribbean’ refer to Caribbean and British people of African heritage. Other terms, such as ‘West Indian’, ‘negro’ and ‘coloured’ are used in their historical contexts, usually before the 1960s and 1970s, the decades in which the term ‘black’ came into popular use.

Though every care has been taken, if, through inadvertence or failure to trace the present owners, I have included any copyright material without acknowledgement or permission, I offer my apologies to all concerned.

A Word on Statistics

No official figure exists for the number of people of African descent living in Britain when war was declared on 3 September 1939. Unlike the United States, the ethnicity of British citizens has never been a requirement for a birth certificate, nor was it recorded in the early census returns. Historians do not agree on an accurate figure. In Black Britannia (1972), Edward Scobie estimated that in the years from 1914 to 1945 there were 20,000 black people in Britain; in Wartime: Britain 1939–1945 (2004), Juliet Gardiner claimed that at the outbreak of the Second World War there were no more than 8,000. Professor Hakim Adi suggested to the author that the most realistic estimate for 3 September 1939 was around 15,000, while Jeffrey Green, author of Black Edwardians (1998), informed the author that, in his opinion, the figure was at least 40,000.

At the outbreak of war, the largest black communities were to be found in the Butetown (Tiger Bay) area of Cardiff in South Wales, Liverpool and the Canning Town and Custom House area of East London’s dockland. In 1935 Nancie Hare’s survey of London’s black population recorded the presence of 1,500 black seamen, and 250–300 working-class families with West Indian or West African heads of households.1

Exact statistics of the number of black men and women from Britain, the Caribbean and Africa who served in the British armed services during the Second World War, or worked for the war effort, are impossible to determine. Ethnicity was not automatically recorded in recruitment papers and no official records of all those working in the many fields of production for the war effort were kept. In 1995, using a variety of Colonial Office sources, Ian Spencer estimated in his contribution to War Culture that, of British Caribbeans in military service during the war, 10,270 were from Jamaica, 800 from Trinidad, 417 from British Guiana, and a smaller number, not exceeding 1,000, came from other Caribbean colonies. The majority served in the Royal Air Force (RAF).2

In We Were There, published in 2002 by the Ministry of Defence, it is claimed:

At the end of the war over three million men [from various parts of the British Empire] were under arms, 2.5 million of them in the Indian Army, over 200,000 from East Africa and 150,000 from West Africa. The RAF also recruited personnel from across the Commonwealth. At first, recruitment concentrated on British subjects of European descent. However, after October 1939 questions of nationality and race were put aside, and all Commonwealth people became eligible to join the RAF on equal terms. By the end of the war over 17,500 such men and women had volunteered to join the RAF, in a variety of roles, and a further 25,000 served in the Royal Indian Air Force.3

In 2007, Richard Smith noted in The Oxford Companion to Black British History:

From 1941 the British government began to recruit service personnel and skilled workers in the West Indies for service in the United Kingdom. Over 12,000 saw active service in the Royal Air Force … About 600 West Indian women were recruited for the Auxiliary Territorial Service, arriving in Britain in the autumn of 1943. The enlistment of these volunteers was accomplished despite official misgivings and obstruction.4

Introduction

I know too well that we would never allow it to be said of us that when the freedom of the world was at stake we stood aside.

Una Marson (1942)

My interest in documenting the experiences of black citizens on the home front and in the armed services began with the stories my adopted Aunt Esther told me. During the war she gave up her job as a seamstress to do war work. She became a fire watcher during air raids. While recording my aunt’s memories, I began searching for other stories of black people in wartime Britain, and I discovered many who have been ignored by historians in hundreds of books and documentaries produced about Britain and the Second World War. For example, when I was a teenager in the 1970s, I borrowed a public library copy of Angus Calder’s The People’s War, first published in 1969. Calder mentioned the existence of a Nigerian air-raid warden in London. So, at an early age, I was made aware that Aunt Esther was not the only black person in Britain during the war.

Despite evidence of racial discrimination, black people contributed to the war effort where they could. In Britain, black people were under fire with the rest of the population in places like Bristol, Cardiff, Liverpool, London and Manchester. Many volunteered as civilian defence workers, such as fire-watchers, air-raid wardens, firemen, stretcher-bearers, first-aid workers and mobile canteen personnel.

These were activities crucial to the home front, but their roles differed from those in the armed services. Factory workers, foresters and nurses were recruited from British colonies in Africa and the Caribbean. Before the Second World War, many in Britain viewed Britain’s colonies in Africa and the Caribbean islands as backwaters of the British Empire, but when Britain declared war on Germany, the people of the empire immediately rallied behind the ‘mother country’ and supported the war effort.

Throughout the empire, black citizens demonstrated their loyalty. Many believed that Britain would give them independence in the post-war years but they recognised that, for this to happen, a battle had to be won between the ‘free world’ and fascism. This instilled a sense of duty in many citizens of the empire. All citizens in the colonies made important contributions, for example, by volunteering to join the armed services, coming to Britain to work in factories, donating money to pay for planes and tanks, and knitting socks and balaclavas.

This important contribution to the war effort has been ignored by many historians. For some, it may seem strange that black people would support a war alongside white people who did not treat them with equality, but the need to win the war, and avoid a Nazi occupation, outweighed this. Sam King, a Jamaican who joined the Royal Air Force in 1944, said, ‘I don’t think the British Empire was perfect, but it was better than Nazi Germany.’1

In the course of my research, many stories came to light about black servicemen and women, and civilians, confronting racist attitudes in wartime Britain, mainly from the American servicemen who were based there. After the USA entered the war in December 1941, the arrival of around 150,000 African American soldiers from 1942 added to the moral panic of ‘racial mixing’. Black American GIs were segregated from white GIs, but black British citizens and their colonial African and West Indian counterparts served in mixed units.

It was not uncommon for non-American blacks in Britain to find themselves subjected to racist taunts and violence from visiting white American GIs. Conscious of the abuse some black Britons were being subjected to, in 1942 the Colonial Office recommended that they wear a badge, to differentiate them from African Americans and to help protect them. Harold Macmillan, then Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, supported the idea and suggested ‘a little Union Jack to wear in their buttonholes’. Needless to say, the idea came to nothing.2

In 2002, when the bestselling author Ken Follett published his wartime espionage thriller Hornet Flight, he wasn’t expecting criticism for including a black RAF squadron leader in his novel. The squadron leader, Charles Ford, is featured in the prologue with a Caribbean accent, ‘overlaid with an Oxbridge drawl’.3 One of Follett’s severest critics was Alan Frampton, who served as a pilot in the RAF between 1942 and 1946. Writing to Follett from his home in Zimbabwe, Frampton said Ford was ‘not a credible character’ and his inclusion was a ‘sop’ to black people who may read Hornet Flight. An angry Frampton apparently threw down the book in disgust when he came across the Ford character.

In his letter to Follett, Frampton said:

For the life of me I cannot recall ever encountering a black airman of any rank whatsoever during the whole of my service, which included Bomber Command. This may have been a coincidence of course but, in England sixty years ago, blacks were few and far between amongst the population and race was not an issue, unlike today with its attendant racial tensions and extreme sensitivity amounting almost to paranoia. He certainly aroused my indignation, remembering as I do, the real heroes of that period in our history, who were not black. I regard myself as a realist but certainly not an apologist for my race. I have read several of your books and enjoyed them. This one I threw down in disgust.4

In his reply to Frampton, dated 19 November 2003, Ken Follett explained:

I’m afraid you’re mistaken. The character Charles was inspired by the father of a friend of mine, a Trinidadian who flew eighty sorties as a navigator in the Second World War and reached the rank of squadron leader. He says there were 252 Trinidadians in the RAF, most of them officers. He was the highest ranked during the war, although after the war a few reached wing commander. He received the DFC [Distinguished Flying Cross] and the DSO [Distinguished Service Order]. With true-life heroes as he, there’s no need for a ‘sop’ to black people, really, is there?5

The Trinidadian who inspired Follett is Ulric Cross (see Chapters 2 and 14) whose response to Frampton was also recorded:

He must be living in a strange world. I am old enough to have a certain amount of tolerance. People believe what they need to believe. For some reason Frampton needs to believe that. When you know what you have done, what people think is irrelevant.6

After 1945, historians of the Second World War, as well as the media (including cinema and television), have portrayed the conflict as one that only involved white men and women. Regrettably, this has continued to be the case, even after the West Indian Association for Service Personnel came into existence in Britain in the 1970s. Since then, the organisation has made great efforts to raise awareness of some of its members’ contributions to the Second World War.

As incongruous as Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s journey on the London underground in Darkest Hour (2017) may have seemed to some cinemagoers, it revealed a united kingdom amongst the people he encountered. His fellow travellers include Marcus Peters (Ade Haastrup), a proud young man of African descent who advises the prime minister that Hitler and the Nazis will never take Piccadilly. This dreamlike sequence is the second time the film’s director, Joe Wright, has acknowledged the black presence in Britain in the Second World War. Ten years earlier, in Atonement (2007), Wright cast Nonso Anozie, a British actor of Nigerian descent, as a ‘tommy’ who accompanies Robbie Turner (James McAvoy) to the Dunkirk evacuation of 1940.

Until then, British cinema had barely acknowledged the existence of black servicemen and women from Britain and its colonies during the Second World War. There is no trace of them in any of the ‘classic’ 1950s war films such as The Cruel Sea (1953), The Dam Busters (1955), Reach for the Sky (1956) and Dunkirk (1958). An exception is Appointment in London (1953) in which Dirk Bogarde, as a wing commander leading a squadron of Lancaster bombers in wartime, has a brief encounter with a black RAF officer, played by a distinguished-looking but unidentified extra.

In America it has taken decades of integrated casting, ‘colour blind’ casting, dramatic licence and a better understanding of its history for filmmakers to portray African Americans in Second World War settings. In American cinema there have been some improvements since 1962 when Darryl F. Zanuck’s The Longest Day, an epic war film about the D-Day landings at Normandy in 1944, failed to acknowledge the contribution of 1,700 African Americans in the first wave establishing the Omaha and Utah beachheads.

With the exception of Joe Wright, British filmmakers are still way behind in acknowledging the presence in the Second World War. Director Christopher Nolan, in the critically acclaimed Dunkirk (2017), failed to acknowledge any of the black British soldiers and merchant seamen who were at Dunkirk. Joshua Levine, the historical consultant for Dunkirk, in an email to the author (12 November 2019) explained that he did try to identify black British soldiers or personnel at Dunkirk. The closest he came was the London-born Cyril Roberts, who was captured before Dunkirk and remained a prisoner of war (POW) until liberated in 1944. Joshua had read about him in my book, The Motherland Calls (2012). However, it is almost certain that other black and mixed-race soldiers, merchant seamen and personnel were at Dunkirk, but identifying them is a problem. In which case, why didn’t Christopher Nolan use dramatic licence? Many directors do.

When Britain declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939, the colonies rallied to support the war effort. For some, it was an opportunity to show their loyalty to the mother country. For others, especially those who volunteered for the RAF, it was a chance to leave home and have an adventure. For the more progressive-minded in the colonies, the war was seen as a route to post-war decolonisation and independence. Ben Bousquet, co-author of West Indian Women at War (1989), said:

Before the war, in all of the islands of the Caribbean, people were agitating for freedom. With the advent of war, they put aside their protestations, they put aside their battles with the British government, and went to sign on to fight.7

In BBC Radio 2’s documentary The Forgotten Volunteers, the presenter Trevor McDonald commented:

Altogether over three and a half million black and Asian service personnel helped to win the fight for freedom but, despite the courage and bravery they showed in volunteering to fight, once the war was over, they found that old suspicions returned. Sometimes it’s so easy to forget. To all the men and women from the West Indies, Africa and the Indian sub-continent, who volunteered to fight in the first and second world wars, we owe a debt of gratitude and respect.8

In 1974, BBC Television screened a ground-breaking historical series called The Black Man in Britain, 1550–1950. It was the first British television series to acknowledge that there had been a black community in Britain for over 400 years. The fourth episode in the series, ‘Soldiers of the Crown’, was one of the first television programmes to acknowledge the contribution made by West Indian servicemen to the Second World War.

Two interviewees stood out, and they summarised the situation in which West Indians found themselves after the declaration of war. They were Ivor Cummings, a black Briton who had been the assistant welfare officer for the Colonial Office, and Dudley Thompson, a Jamaican who had served as a flight lieutenant in the RAF from 1941 until 1945 and with 49 Pathfinders Squadron. He was awarded several decorations. Towards the end of the war Thompson served as a liaison officer with the Colonial Office where he assisted Jamaican ex-servicemen who wanted to settle in London.

In ‘Soldiers of the Crown’, Cummings explained that he had been denied a commission in the RAF in 1939:

That rule [in the King’s Regulations] excluded all of us. I couldn’t join the Royal Air Force because I was not of pure European descent. We were able to get rid of that ridiculous disqualification otherwise we should not have been able to mobilise our volunteers in the way that we did. They wouldn’t have qualified for commissions.

When the rule referred to by Cummings was abandoned, it was too late for him to join the RAF because he had accepted a post with the Colonial Office. He said:

It is not done nowadays to talk about patriotism and the mother country because the Empire does not exist. It did exist in 1939 and there was no doubt at all that there was a great feeling of attachment and affection to this country by the colonies, in Africa and particularly in the West Indies.

Cummings commented that one of the most important things that happened to West Indians during the war was the exposure to a different type of government, one that enabled them a certain amount of freedom, a better way of life, and access to a higher standard of education:

So, when they returned home after the war, they returned to the same government they had left. It was autocratic and people didn’t want this. They resented this and the fact that the economic conditions in these places were absolutely appalling. For the returning servicemen and women, the officials, the governors, and others were very tiresome people indeed and didn’t know how to deal with those who had been away in the war. After the war I was sent out to the Caribbean and I visited the three major islands, including Jamaica, and I was absolutely appalled. There were no opportunities for these people. The whole thing quite horrified me and I told everyone exactly what I felt about this. It was quite clear to me that this was a watershed. This whole war experience had been a watershed, that there were going to be changes.9

For many in the colonies, post-war reform was slow, but the changes they expected eventually came with independence: for example, Ghana (1957), Nigeria (1960), Jamaica (1962), Trinidad and Tobago (1962), Kenya (1963), Guyana (1966) and Barbados (1966).

In ‘Soldiers of the Crown’, Dudley Thompson described how he felt on arriving in England from Jamaica in 1940:

As a colonial I would say the effect is confusing in that Jamaica – which you would consider a model colony – always saw the whites as leaders, governors, heads of departments, executives, and so on. You grew up with it. You knew that in the police force, no matter how great you were, you could never get promotion. Those were limitations you accepted. You weren’t even militant about it. And then you come to a country where, for the first time, you see white street sweepers, white bus drivers and other more menial tasks that you never imagined white people did. It was an eye opener. Things were not as you had always expected it to be, and it was a psychologically traumatic situation and more than confusing.

In England during the war, Dudley discovered that it was possible to meet – and make friends with – white people:

You made friends, and you got used to the English way of life. There was a certain amount of courtesy from the English which you did not experience at home and you just adjusted into the English situation which was far from unpleasant. You were accepted as a soldier at a time when soldiers were coming from all parts of the Empire. You were rather proud that you wore a different flash on your shoulder because you saw Poland, France, Australia, Jamaica identified. You were just one of the sections of people whom England was glad to receive as fighting for the general cause.

However, racial conflict was never far away:

You’d find at dance halls there were incidents where they felt black soldiers should not be in that place and sometimes they came from people like the Rhodesian forces who were visiting as well. And you did find occasional cases of friction, so much so that towards the end of the war, liaison officers were created within the Royal Air Force to take care of these situations. I was a liaison officer and from time to time was called to various places where there were disruptions, fights, and ugly incidents that needed smoothing out.

In Jamaica, access to education was restricted, but in wartime Britain, Dudley discovered a whole new world of knowledge opened up to him:

In the colonies there was very limited reading material, most of the books that would be interesting were banned anyway. There was no University. You come to England and find you’ve got a far more liberal selection of material. You can walk into any library and pursue studies. You can pursue studies of your own country much more widely than you could at home.

Dudley summarised the effect the war had on people from the colonies:

The effect on the armed forces, and the civilians who were munitions workers, was to show that, in England, while you were treated as a normal, average citizen, there were many more opportunities which were open to you there than were open to you at home. You could learn skills, at universities and technical schools, and you became proficient in those skills. Those skills were either non-existent at home or reserved for white people who were ruling you rather than for yourself. So, to a great extent it tremendously increased your self-reliance. The other experience was to show that you were a foreigner and that when you went home you would have to be master in your own house. I would say it increased your sense of national feeling and for the first time you felt that you had to make your own home your own. You also met people from other parts of the Empire who felt similarly, particularly from Africa.10

The freedom that the British have enjoyed since 1945 was made possible by the support of the peoples of their former empire. These people made a major contribution to the winning of that freedom. They fought hard for it, and some gave their lives. However, recognition for this support – and the sacrifices made – has been almost non-existent. The historian Ray Costello has offered an explanation for this omission. He said that Britain had been reluctant to show the world that black servicemen and women from Britain and the colonies had played a part in freeing the oppressed, ‘because they were afraid that it would feed the desire for independence’:

If black people are shown to have the capacity for bravery it makes them human, heroes even. And heroes should have freedom and independence. Britain did not want that. It was more difficult to conceal our contributions at the end of World War II because of the sheer numbers who fought. The omission of the contribution of blacks to the British armed services is a crime comparable to slavery.11

There have been a few exceptions. For example, on 22 June 2017 the first memorial to African and Caribbean servicemen and women was unveiled in Windrush Square, Brixton, and this was made possible by the hard work of Jak Beula, CEO of the Nubian Jak Community Trust.

1939 Register of England and Wales

The 1939 Register provides a snapshot of the civilian population of England and Wales just after the outbreak of the Second World War. It was taken on 29 September 1939 and the information was used to produce identity cards and, once rationing was introduced in January 1940, to issue ration books. Information in the register was also used to administer conscription and the direction of labour, and to monitor and control the movement of the population caused by military mobilisation and mass evacuation.

The following list includes a diverse range of black citizens who are known by the author to have been living in England and Wales at the time the Register was compiled. Additional information, including their country of birth, are noted in italics.

Greater London

Robert W. Adams

b. 18/5/1902 – actor and Air Raid Precautions stretcher bearer

33 Squire’s Bridge Road, Sunbury-on-Thames, Middlesex

(aka Robert Adams) (British Guiana, later Guyana) (Died 1965)

Adenrele Ademola

b. 2/1/1916 – probationer nurse

Bassett’s Way, Orpington, Kent

(Nigeria, West Africa)

Baba O. Alakija

b. 1/10/1914 – law student

Flat 1, 28 Kensington Church Street, Kensington

(aka Baba Oyeola Alakija) (Nigeria, West Africa) (Joined the RAF)

Amanda C.E. Aldridge

b. 10/3/1866 – teacher of singing

17 Arundel Gardens, Kensington

(aka Amanda Ira Aldridge) (United Kingdom) (Daughter of the Shakespearean actor Ira Aldridge [1807-67]) (Died 1956)

Granville ‘Chick’ Alexander

b. 25/8/1905 – waiter

6 Howland Street, St Pancras

(Jamaica) (Dancer who worked in civilian defence) (Died 1969)

Rupert Arthurs

b. 15/3/1894 – tailor (master)

26 Benedict Road, Lambeth

(British Honduras, later Belize) (Committee member of the League of Coloured Peoples)

Amy Barbour-James

b. 25/1/1906 – companion help

14 Golf Close, Harrow, Middlesex

(United Kingdom) (Committee member of the League of Coloured Peoples) (Died 1988)

Carl Barriteau

b. 7/2/1914 – musician

5 Marchmont Street, Holborn

(Trinidad) (Died 1998)

Stafford Barton

b. 2/5/1915 – professional boxer and Air Raid Precautions Warden

25 Conway Street, St Pancras

(Jamaica) (Joined RAF and was killed in action in 1943)

Dr Cecil Belfield Clarke

b. 12/4/1894 – Registered Medical Practitioner

Belfield House, Greenhill Park, Great North Road, East Barnet, Hertfordshire

(Barbados) (Pan-Africanist) (Died 1970)

Rowland W. Beoku-Betts

b. 3/1/1914 – law student

1 South Villas, St Pancras

(West Africa) (President of the West African Students’ Union)

Augustus (Joslin) Bingham

b. 5/11/1894 – variety artiste

Flat 4, 9 Charing Cross Road, Westminster

(aka Frisco) (Jamaica) (Nightclub owner in London’s West End)

Peter Blackman

b. 28/6/1909 – writer and journalist

61 Glenmore Road, Hampstead

(Barbados) (Pan-African Marxist and scholar, also committee member of the League of Coloured Peoples)

Cyril (McDonald) Blake

b. 27/10/1897 – artiste-musician

10 Rothwell Street, St Pancras

(aka Cyril Blake) (Trinidad) (Died 1951)

Leonard Bradbrook

b. 18/10/1904 – no profession; Air Raid Precautions first-aid stretcher

42 Fitzalan Street, Lambeth

(United Kingdom) (Civilian defence worker) (Died 1991)

Buddy Bradley

b. 25/7/1905 – dance teacher

8 Radnor Place, Paddington

(USA) (Film and stage choreographer) (Died 1972)

Morris Brown

b. 9/4/1909 – hairdresser

22A High Road, Kilburn, Hampstead

(United Kingdom) (Older brother of jazz musician Ray Ellington)

Josephine (Esther) Bruce

b. 29/11/1912 – dress machinist

23 Eli Street, Fulham

(aka Esther Bruce) (United Kingdom) (Seamstress and hospital cleaner who volunteered as a fire watcher) (Died 1994)

Joseph Bruce

b. 25/10/1881 – coach painter

4 Dieppe Street, Fulham

(British Guiana, later Guyana) (Coach painter, father of Josephine E. Bruce) (Died 1941)

Rita (Evelyn) Cann

b. 24/1/1911 – stage artist

143 Fellows Road, Hampstead

(aka Rita Lawrence) (United Kingdom) (Died 2001)

Astley (Campbell) Clerk

b. 2/12/1906 book keeper/accountant

35 Norfolk Place, Paddington

(Jamaica) (died 1961) (born in Spanish Town, Jamaica of Scottish and African descent, Astley came to Britain in 1936 and from 1939-45 he was a Metropolitan Police Reserve Constable in ‘D’ Division (Marylebone))

Avril Coleridge-Taylor

b. 8/3/1903 – musician and ambulance driver

44A Loudoun Road, St Marylebone

(United Kingdom) (Composer and orchestra conductor, daughter of the composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, 1875–1912) (Died 1998)

Joseph Cozier

b. 8/7/1895 – general labourer

27 Catherine Street, West Ham, Essex

(British Guiana, later Guyana) (head of the Cozier family in London’s East End)

Frederick Crump

b. 26/1/1902 – artist (travelling)

19 Rochester Road, St Pancras

(aka Freddie Crump) (USA) (Musician – drummer)

Francisco A. Deniz

b. 31/8/1912 – dance band musician

33 Northview, Tufnell Park Road, Islington

(aka Frank Deniz) (United Kingdom) (Died 2005)

Clara E. Deniz

b. 30/9/1911 – dance band musician

(aka Clare Deniz) (United Kingdom) (Wife of Francisco Deniz) (Died 2002)

Joseph W. Deniz

b. 10/9/1913 – musician

196 Westbourne Park Road, Kensington

(aka Joe Deniz) (United Kingdom) (Died 1994)

Yorke de Souza

b. 19/3/1913 – student musician

249 Camden Road, Islington N7

(Jamaica)

Arthur Dibbin

b. 25/10/1901 – travelling trumpet musician

28 Holcombe Road, Tottenham

(United Kingdom)

Evelyn Dove

b. 4/1/1902 – travelling variety artist

23 Roland Way, Kensington

(United Kingdom) (Died 1987)

Rudolph Dunbar

b. 5/4/1907 – journalist

Chiswick Mall Studio

(British Guiana, later Guyana) (Classical musician, orchestra conductor and war correspondent) (Died 1988)

Ekpenyon Ita Ekpenyon

b. 30/12/1898 – artist (films) and Air Raid Precautions Warden

26 Clipstone Street, St Marylebone

(Nigeria, West Africa) (Died 1951)

Frank Essien

b. 10/11/1907 – music hall artist

88 Jermyn Street, Westminster

Titus O. Etiwunmi

b. 26/5/1914 – science student

1 South Villas, St Pancras

(West Africa)

Rudolph Evans

b. 23/2/1897 – musician and entertainer

25 Conway Street, St Pancras

(aka Andre de Dakar) (Panama, South America of Jamaican parents) (Owner of the Caribbean Club in London’s West End 1944–53) (Died 1987)

Ernest Eytle

b. 18/3/1918 – student

46 Regent Street, St Pancras

(British Guiana, later Guyana) (Cricket commentator)

Nathaniel Fadipe (Akinsemi)

b. 2/10/1893 – lecturer and journalist

23 Regent Square, St Pancras

(Nigeria, West Africa) (Died 1944)

Kier (Farad) Fahmey

b. 1871 – extra, film actor

29 Dieppe Street, Fulham

(North Africa)

Napoleon Florent

b. 8/9/1874 – theatrical artist

19 Camberley House, St Pancras

(St Lucia) (Head of the Florent family, his son Vivian was killed in 1944 while serving in the RAF) (Died 1959)

+ Josephine Florent b. 5/7/1910 – typist clerk

+ Leon Florent 18/6/1912 – cook

+ Emile Florent 1/10/1916 – painter and decorator

Cassandra Foresythe

b. 25/7/1910 – shorthand typist

19 Pierrepoint Road, Acton, Middlesex

(United Kingdom) (Sister of pianist and composer Reginald Foresythe)

Marcus Garvey

b. 17/8/1887 – journalist

53 Talgarth Road, Fulham (home address)

2 Beaumont Crescent, West Kensington (office address)

(Jamaica) (Political activist) (Died 1940)

Winifred Goodare

b. 19/2/1911 – dancer

25 Conway Street, St Pancras

(aka Laureen Goodare) (United Kingdom) (Died 1983)

Phoebe Graham

b. 29/4/1899 – variety artiste (travelling)

11 Grenville Street, St Pancras

(aka Pep Graham) (United Kingdom)

Sidney Graham

b. 25/1/1897 – mercantile marine/ships fireman

24 Crown Street, West Ham, Essex

(Barbados)

Isaac Hatch

b. 21/8/1892 – artist singer

79c Tottenham Court Road, St Pancras

(aka Ike Hatch) (USA) (Nightclub owner) (Died 1961)

Josephine (Lucy) Haywood

b. 16/5/1912 – dancer

61 Great Ormond Street, Holborn

(aka Josephine Woods/Josie Woods) (United Kingdom) (Died 2008)

Louis (Fernando) Henriques

b. 15/6/1916 – student and Auxiliary Fire Service

10 Swiss Terrace, Hampstead

(aka Fernando Henriques) (Jamaica) (Scholar) (Died 1976)

Pauline Henebery

b. 1/4/1914 – unpaid domestic duties

Flat 2 10 South Hill Park Gardens, Hampstead

(aka Pauline Henriques) (Jamaica) (Actress and broadcaster) (Died 1998)

Bert Hicks

b. 4/7/1894 theatrical manager

23 Bruton Lane, City of Westminster

(Trinidad) (Nightclub owner, husband of Adelaide Hall) (Died 1963)

+ Adelaide Hall b. 20/10/1901 (USA) (Entertainer) (Died 1993)

Marko Hlubi

b. 26/8/1903 student

9 Museum Street, Holborn

(South Africa)

Leslie Hutchinson

b. 7/3/1900 – BBC artiste and variety star

31 Steeles Road, Hampstead

(aka Leslie ‘Hutch’ Hutchinson) (Grenada) (Died 1969)

+ Ivan Hutchinson b. 6/2/1902 – dependent on Leslie Hutchinson

(Grenada) (Brother of Leslie Hutchinson)

Gerald Jennings

b. 13/10/1893 – musician (band leader) + ambulance driver

Flat 2, 21 Southey Road, Lambeth

(aka Al Jennings) (Trinidad) (Died 1980)

Irene B. Jerome

b. 26/1/1891 – unpaid domestic duties

19 Rochester Road, St Pancras

(aka Irene Howe) (Mother of Cyril Lagey and John Lagey, also an actress) (Died 1975)

Kenrick Johnson

b. 10/9/1914 orchestra leader

23 Gloucester Avenue, St Pancras

(aka Ken ‘Snakehips’ Johnson) (British Guiana, Guyana) (Died 1941)

Amelia E. King

b. 25/6/1917 – box maker

111 John Scurr House, Stepney

(United Kingdom) (died 1995)

+ Henry King b. 16/7/1887 greaser Sombardy (ship)

+Ada A. King b. 1/9/1916 bag machinist (heavy work)

+ Frances King b. 21/4/1920 unpaid domestic duties

+ Fitzherbert King b. 18/4/1922 engineering trade

Reverend Israel Kuti

b. 30/4/1891 – minister and professor

1 South Villas, St Pancras

(West Africa)

Cyril J. Lagey

b. 15/1/1912 artist

19 Rochester Road, St Pancras

(United Kingdom) (Musician and comedian) (Died 1999)

John. A. Lagey

b. 20/4/1920 – general labourer

19 Rochester Road, St Pancras

(United Kingdom) (Later known as Johnny Kwango, professional wrestler) (Died 1994)

Alexander Lofton

b. 13/3/1879 – variety artist/vocalist

71 Monkton Street, Lambeth

(USA) (Died 1955)

Benjamin C. MacRae

b. 21/7/1917 ice cream maker

29 Holly Road W4, Brentford and Chiswick, Middlesex

(United Kingdom) (Served in the British Army in WW2) (Died 2001)

Leo D.C. March

b. 19/9/1914 – dental surgeon

26 Hollingbourne Road, Camberwell

(Jamaica)

Ernest Marke

b. 30/8/1901 – medical herbalist

43 Mornington Crescent, St Pancras

(Sierra Leone) (Died 1995)

Una Marson

b. 6/2/1905 – journalist

14 The Mansion, Mill Lane, Hampstead

(Jamaica) (Poet and dramatist who worked as a radio producer and presenter for the BBC) (Died 1965)

Emmanuel A. Martins

b. 8/12/1899 – artist

99 Kings Cross Road, St Pancras

(aka Orlando Martins) (Nigeria, West Africa) (Film and stage actor) (Died 1985)

Ras Prince Monolulu

b. 10/10/1881 – tipster, turf adviser

55 Howland Street, St Pancras

(British Guiana, later Guyana) (Died 1965)

Dr Harold A. Moody

b. 8/10/1882 – medical practitioner

164 Queens Road, Camberwell

(Jamaica) (Community leader, president of the LCP and head of the Moody family) (Died 1947)

+ Dr Christine Olive Moody b. 12/5/1914 – medical practitioner

+ Harold Ernest A Moody b. 1/11/1915 – student

+ Charles A Murcott Moody (aka Charles ‘Joe’ Moody) b. 15/4/1917 – student

John Nit

b. 27/8/1907 – professional dancer and Air Raid Precautions Warden

41 Howland Street, St Pancras

(USA)

Ladipo Odunsi

b. 14.1.1911 – law student

1 South Villas, St Pancras

(West Africa)

George Padmore

b. 28/6/1900 – author and working journalist

23 Cranleigh House, St Pancras

(aka Malcolm Nurse) (Trinidad) (Pan-Africanist and member of the Communist Party) (Died 1959)

Uriel Porter

b. 5/5/1911 – singer

34 Mornington Crescent, St Pancras

(Jamaica) (Died 1985)

Harry Quashie

b. 3/12/1899 – artist

4 Rothwell Street, St Pancras

(Ghana) (Film and stage actor) (Died 1982)

George A. Roberts

b. 1/8/1891 – exhibition attendant and Auxiliary Fire Service

29E Lewis Trust Dwellings, Warner Road, Camberwell

(Trinidad) (Committee member of the League of Coloured Peoples) (Died 1970)

Edmundo Ros

b. 9/12//1910 – musician artiste

77 Linden Gardens, Kensington

(Trinidad) (Died 2011)

Winifred Scott

b. 29/7/1917 – probationer nurse

26 Selbourne Road, Chiselhurst and Sidcup

(United Kingdom)

Cornelia Estelle Smith

b. 29/4/1875 – variety and film artist

14 Brook Drive, Lambeth

(aka Connie Smith) (USA) (Died 1970)

Norris Smith

b. 18/2/1883 – music hall artist

88 Jermyn Street, Westminster

(USA) (Died 1959)

Ladipo Solanke

b. 3/3/1893 – barrister at law

1 South Villas, St Pancras

(Nigeria, West Africa) (Founder of the West African Students’ Union) (Died 1958)

Opeolu ‘Olu’ Solanke

b. 12/4/1910 – unpaid domestic duties

1 South Villas, St Pancras

(Nigeria, West Africa) (Wife of Ladipo Solanke)

James M. Solomon

b. 3/6/1880 – variety artist

101 Walton Street, Chelsea

(West Indian-born film and stage actor) (Died 1940)

Fela Sowande

b. 29/5/1905 – dance pianist

20 Northview, Tufnell Park Road, Islington

(Nigeria, West Africa) (Musician and composer) (Died 1987)

Louis Stephenson

b. 2/6/1907 – musician

249 Camden Road, Islington N7

(Jamaica)

Rita (Kathleen) Stevens

b. 2/10/1909 – artist on tour

Hillmarton Road, Islington

(United Kingdom)

Monteith Tyree

b. 19/7/1902 musician

155 Brixton Road, Lambeth

(aka Monty Tyree) (United Kingdom) (Son of African American singer and guitarist Monteith Tyree)

Mathias Vroom

b. 27/3/1898 – artist

16 Mornington Crescent, Islington

(West Africa)

+ Frances Vroom b. 15/2/1904 – artist

(United Kingdom)

Edward Henry Wallace

b. 16/11/1871 – vocalist and travelling instrumentalist

16 Kennington Road, Lambeth

(USA) (Died 1965)

Otto L. Wallen

b. 31/1/1896 – medical practitioner

48 Coram Street, Holborn

(Trinidad)

Elisabeth Welch

b. 27/2/1909 – theatre artist

1 Cottage Walk, Chelsea

(USA) (Died 2003)

David Wilkins

b. 25/9/1914 – musician

49 Sussex Gardens, Paddington

(aka Dave Wilkins) (Barbados) (Died 1990)

Charles Wood

b. 18/8/1914 – music hall artist

14 Maple Street, St Pancras

(United Kingdom) (Brother of Josephine (Lucy) Haywood (see above))