Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

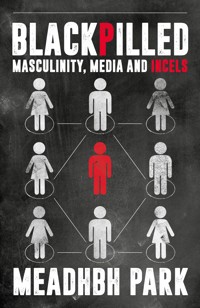

Incels – involuntary celibates – are often cast as violent, misogynistic loners, consumed by resentment towards women. With shocking tragedies like the 2014 Isla Vista killings and the 2024 Bondi Junction stabbings heightening fears about the threat they pose, understanding this phenomenon has never been more crucial. But it's important not to view incels as aliens who came down to earth on women-hating spaceships from a distant women-hating planet. Though their belief system – referred to as the 'blackpill' – is no doubt extreme, they haven't constructed it from nothing. These young men are shaped by the media they consume and the society that surrounds us. In Blackpilled, Meadhbh Park takes an unflinching look at the incel movement through the lenses of masculinity and media studies. Drawing on interviews with incels across the globe and analysing cultural touchstones such as The Matrix, Fight Club, Taxi Driver, Euphoria, Joker and Blade Runner 2049, Park uncovers the origins of their beliefs and what they really think. She also examines potential ways to help incels break free from the nihilistic and hate-fuelled grip of the blackpill. With extremist misogyny on the rise and governments debating whether incels should be labelled a terror threat, Blackpilled delivers urgent, thought-provoking conclusions that couldn't be more timely.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 497

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

“An extensive deep dive into incel culture that explores how our society’s misogyny and cultural stereotypes have helped to shape the online subculture and its ugly attitudes towards women.”

Siân Norris, author of Bodies Under Siege: How the Far-Right Attack on Reproductive Rights Went Global

“A compelling and important book. It demonstrates that the misogynistic extremism of the incel community does not exist in a vacuum, detached from societal ideas, but rather originates from the heart of society – from its media.”

Susanne Kaiser, author ofPolitical Masculinity: How Incels, Fundamentalists and Authoritarians Mobilise for Patriarchy

“A forensic examination of the online incel movement that is both critical and compassionate. I came away from Meadhbh Park’s important investigation with a far better understanding of what draws men into misogynistic online subcultures. This book is essential reading for anyone who wants to understand what is happening in the darker corners of the internet.”

James Bloodworth, author of Lost Boys: Undercover Adventures in Toxic Masculinityii

“Blackpilled is a timely and critically important contribution to the wider public understanding of the incel phenomenon. Grounded in research with incels (an achievement in itself!), Meadhbh Park addresses this vexed issue with intellectual depth, nuance, reflexivity and, crucially, empathy. Blackpilled sheds new light on this often-misunderstood online world and its misogynistic ideology, demonstrating both the vulnerabilities of the young men drawn in and their violent potential. It’s an essential text for the study of online misogyny and radicalisation.”

Josh Roose, co-author of Masculinity and Violent Extremism and associate professor at Deakin University, Australia

“Blackpilled provides a key insight into the very dark and complex issues currently influencing and spreading among vulnerable young men online. Meadhbh Park performs a worthy dissection of a complicated web of difficult concepts and has created a compelling text of essential reading for anyone wishing to better understand the rise of incel ideology.”

Travis D. Frain OBE DL, co-founder of Survivors Against Terror

iii

Contents

INTRODUCTION

When I was a child, I fell in love with film. From as early as I can remember, I religiously watched every movie I could. They became a roadmap and a window into the world and my place within it. Films helped me to understand human experiences such as bravery, love, passion, perseverance, violence, heartbreak and loss. They became a gateway to worlds foreign to me – magical worlds, worlds of times gone by and future worlds too. They shaped my attitudes and opinions of other people, places, ideas, of what’s right and wrong and the myriads of grey in between. I am not alone in this, as numerous studies show the influence that films have on even very young children.1

As humans, we have always been drawn to storytelling; it’s in our DNA. Before films and television, there were books; before books, we told oral stories and drew cave paintings. Telling stories is an exclusively human phenomenon; it’s one of the greatest distinctions we have to animals, and it’s something that every country, every culture, has in common. From ancient myths to epic poems to urban legends, we communicate with stories. While the medium of storytelling has changed, from sitting around fires xto Netflix and video games, we still need stories in our lives. Research has shown that we are all influenced by the media we consume and that it plays a key role in how we see ourselves, others and the world. Repeated tropes and narratives can solidify certain ideas in our minds, especially those relating to certain groups of people and genders. This fact was truly brought home to me when I started working to understand extremists and immediately noticed how tropes and narratives from films, TV shows and other media were frequently referenced in extremist conversations. Extremists, like the rest of us, use stories to inform their understanding of the world and to also help craft their ideologies and worldviews.

There are very few moments in life when your whole perspective changes, but when I first started to notice the invisible thread between our depictions of men in stories and the silent (and not so silent) effects on boys and men, it changed my understanding of men, gender relations and society more broadly. When Andrew Tate, the infamous extremist misogynist, shot into our social ether like a dinosaur-killing meteor, many people were caught off guard. It wasn’t obviously apparent to many people, even many men, why someone like him could have accumulated such a huge and fanatic fanbase of mostly teenage boys and young men. It wasn’t clear why boys or men would feel any exclusive type of frustration or fear or why they would want to emulate someone who seemed like a cartoon character. But the fact that Tate was a surprise to so many was a surprise to me.

We’ve had thousands of years of messaging to men that they should be dominant, in control, be able to utilise violence and be the providers and protectors. With the rise of feminism, women have gained more power, influence and independence than ever xibefore, and with this there has been a shift in society’s ideas about gender, with the traditional ideal of male dominance now often being deemed ‘toxic’. But many of the messages broadcast by today’s media still lionise traditional versions of masculinity, despite the fact that these are not always conducive to progressive values of equality. This is creating a disconnect between the messages men are receiving from the media and those they are receiving from society on how they’re expected to act in this new social climate. Confusion abounds, and this has led to many men harkening back to times gone by when a man’s role was clearly defined and key to his success in personal, social and political landscapes. While not all men fit into traditional masculinity, and many men suffered under the pressures to conform to this version of masculinity, and still do, there was still a clear roadmap in times past for men that left little confusion over how they were expected to behave and act. There was also an overt message of power in attaining traditional masculinity, which was in itself alluring. Being a heterosexual masculine man meant being dominant and having a sense of control in nearly every area of life, from the social sphere to work to the political arena. Of course, the complexities of class, race and ethnicity played a role in how much power men truly wielded in their lives, but at least in the overall understanding of what it meant to be masculine, dominance over women and others as well as control were key aspects. The changing tides of gender dynamics has led to a loss of this control and clarity for heterosexual men who want to find a way to feel respected, attractive and certain of what they are expected to be. Tate tapped into this fear of a loss of masculine control, and so his popularity among young, disillusioned men shouldn’t have been a surprise.

The messages that men receive from media have generally been xiiconsistent over time – men are strong, dominant leaders. But the messages women receive about femininity have notably changed over recent decades due to the rise of feminism. As early as the 1970s, women were starting to be more frequently depicted as having their own agency, independence and breaking free of the rigid social norms like getting married and becoming a housewife. Now, popular movies and TV shows often portray women in positions of power, whether it be political, in the workplace or simply having more agency over their own lives. While not without controversy, female characters have also successfully broken into male-dominated genres, such as science fiction and action. It is not unusual any more to see a gun-slinging female character who saves the day; although, it can be argued that there are still issues with how these characters are depicted. Generally, however, it can be said that the messages around women and femininity have progressed, especially when films are produced with a female audience in mind.

For male characters, it’s almost as if feminism never really occurred, or if it did, it was some hazy event in the background. Male characters are still widely depicted in ways that highlight the traditional masculine qualities that were idealised by our great-grandfathers. Male characters who deviate from those qualities are still viewed as ‘not cool’, ‘feminine’, ‘beta’, ‘cucked’ (cuckholded) or as generally less of a man. The characteristics associated with traditional masculinity include physical strength, stoicism, risk-taking, assertiveness, wealth, self-reliance, status, fearlessness, protectiveness, aggression, sexual prowess, extreme perseverance, achievement, ruthlessness, violence (or readiness to fight) and domination. These traits could be interpreted in a positive or negative light depending on the characters. While some of these behaviours xiiiare overtly negative, a trait such as ‘violence’ is often depicted as a positive attribute, especially in war films where male heroes use violence to protect their homes or families. If you were to create the most positive male character using these traits as a guide, you could create a character such as Aragorn, from LordoftheRings, or Superman. Embodying these attributes does not necessarily mean a character has to be bad or ‘toxic’, but even at their best, these traits create certain pressures for men. It’s common for male heroes to reject help and to be extremely self-reliant, which is a common pressure men feel today. All of these characteristics also do not freely allow for a collaborative effort with women. In media, for male heroes to accept the help of someone else would be seen as bad enough, unless it was from male comrades in arms, but accepting the help of a woman is often viewed as emasculating. In fact, in the cases where the male hero does have help or works side by side with a female character in an equal partnership, it is often highlighted in the films as noteworthy in itself and a part of the story (with some exceptions, such as Twister[1996] and TheEdgeofTomorrow [2014]).

On closer inspection of how men are depicted in media, it should be unsurprising that these influences can have a detrimental effect on how men are perceived in society, how they view themselves and how they view others too.

When I was finishing my MA course in 2020, I had just started to understand how frameworks of gender and masculinity play a pivotal role socially and politically, particularly in the arena of conflict and international relations. Little did I know that the education I was getting through my university course was only scratching the surface of what was bubbling underneath us all. I wasn’t very online; I barely had an Instagram account, which I used mainly for chatting xivto my friends. I didn’t have TikTok or Twitter and only occasionally scrolled Reddit, so I had no clue of the enormous ecosystem of groups that were forming online over shared grievances around gender relations. It was like there was a whole other side of our reality that I, and many others, had absolutely no idea about, which was seeping into our political and social lives. Finding it felt like discovering a largely undetected and under-explored underworld, moving like magma beneath the surface, causing the tectonic plates of our society to shift. I realised that we were seeing the effects of this online world in our offline lives, but many of us had no idea what was happening or why. And that’s when I found myself journeying into this underworld, this other dimension, as dark and murky as it was, but like a bloodhound with a scent, I wanted to follow the trail and see where it went.

Incels – involuntary celibates – are typically viewed as misogynistic, violent loners who have actively turned their back on society and unleash their frustrations at women both on- and offline. Violent real-world attacks have originated from this community, such as the 2014 mass shooting in Isla Vista, California, which led to the murder of seven people, including the shooter, Elliot Rodger, who posthumously became the poster boy for the incel community. There have also been other mass attacks, including thwarted plots, that have been linked to incel narratives and the incel community, garnering attention from the media and law enforcement. Efforts to prevent violence by this community have run into controversy, including around the official designation of incels as a terrorist movement in Canada after two deadly attacks: the Toronto van attack in 2018 and an attack on a massage parlour in Toronto in 2020. Classifying attacks and ideologies that centre on women has also been muddied since misogyny is not considered a hate crime xvin most countries, including the United Kingdom. The confusion surrounding ideological misogyny versus its socially embedded variety, which has also led to abuse and sometimes even homicide, has culminated in a strange situation in which these attacks sit in a no-man’s land between terrorism and normal criminality.

Incels have gained the notoriety of being the most violent and aggressive misogynists online, which is a feat considering the level of misogyny that is rampant on most online platforms. Their reputation proceeds them in many ways, as the label ‘incel’ is often now conflated to mean ‘misogynist’ and has been the insult du jour used against any man who is deemed to be misogynistic. Incels have increasingly been viewed as patenting misogyny, as if they are the creators and sole proprietors of sexism. This has allowed some other groups and individuals off the hook, while also ignoring the normality of misogyny in the tapestry of our society. That’s not to say that extremist and misogynistic incel ideologies don’t deserve the title of being misogynist, even violently misogynist, but we should also question whether incels have become convenient culprits to blame for all of the extremist misogyny now brewing. The widespread blanket demonisation of incels has also led to a lack of desire to understand why people are drawn into incel communities and ideologies. Instead, incels have been viewed as bizarre bogeymen akin to serial killers and lost causes and so all of their grievances, stories and feelings are often derided, denigrated and dismissed. The implications of this have led to backlash, including more young men and boys becoming frustrated, feeling unheard and finding themselves resonating more with these groups and worldviews.

In the field of preventing and countering violent extremism, understanding how to balance accountability and empathy is continually discussed. When I began my career, I was lucky to have xvibeen a volunteer for the American organisation Life After Hate, where I met former neo-Nazis and gang members who have now dedicated their lives to helping others leave the violent far right. My conversations with members of that organisation were transformative and brought a whole new level of understanding as to why people join hate movements. I’ve always had empathy for people in difficult situations, especially when mental health and isolation were involved. As a young adult, I spent some time dealing with my own mental health issues and this taught me how easy it could be for some people to slip through the cracks. While I was lucky to have a supportive family, I realised that many people don’t have the necessary support network to help them through those times and for some young people, this can be the difference between having a chance in life or not. In my many insightful conversations with members of Life After Hate, I learned first-hand what can happen when family support fails, when mental health takes its toll, when isolation leads to frustration and when desperate attempts to belong become misdirected. Rightfully, some people will say that adverse life experiences do not excuse harmful behaviour, especially when it comes to extremism, and that individuals have to take responsibility for their own actions. After meeting members of Life After Hate, I witnessed how the majority of people who leave hate movements do in fact hold themselves accountable; they don’t and can’t forget what they’ve done and finding forgiveness for themselves is often more difficult than being forgiven, sometimes even impossible.

When we think about extremists and terrorists, we depersonalise them because we want so much to see them as monsters. Perhaps a case could be made that certain people are beyond redemption, that their crimes are so great that there is no way back for them and there is no forgiveness. Yet we need to find ways to move forwards xviito rehabilitate people as best we can and find ways to reconnect with them. Desmond Tutu, the late Archbishop of Cape Town, had a lot to say about the power of forgiveness and how it’s a bridge not only to personal healing but to societal healing too.

When talking about incels, I always say that it’s important not to view them as aliens that came down to earth on spaceships from a distant women-hating planet. While their ideology – referred to as the ‘blackpill’ – is no doubt extreme, they haven’t constructed this belief system from nothing. There are some people and groups that hold beliefs that are rather fantastical and creative, such as David Icke’s reptilian overlords and the flat earthers, as well as certain cults that believe in intergalactic travel or great awakenings usually involving mass suicide. But even then, in the wackiest conspiracies and groups, you can still see glimpses of some mainstream cultural elements such as sci-fi narratives, antisemitism and fundamentalist interpretations of religion. Incels, however, are not even that creative – the majority of incels reject ideas that intrude on mystical, extremely conspiratorial or highly irrational realms. Instead, incels gather their sources, narratives and ideas from messages that are already all around them, messages that we have all heard and seen in the media and other places in society.

Throughout my research into the incel phenomenon, I’ve noticed that incels frequently refer to the same movies and TV shows. They detail how they feel these productions have influenced their worldview and have perhaps even been part of their radicalisation or entry into the blackpill. I’ve also noticed how, in the incel community, seemingly complicated ideas they put forward can be easily understood by examining them through the lens of popular media and culture. Not only can showing these media influences on incels help other people to better understand what they are actually xviiitalking about; it can also highlight why incels feel that these ideas they’re sharing are so important.

Of all the films that will be discussed in this book, TheMatrix(1999) is possibly the most culturally significant and the most intwined with the incel worldview, having birthed the concept of the ‘redpill’ and therefore the ‘blackpill’. TheMatrixtackles the topics of society, reality, free will, technology and the dawning of artificial intelligence and its ethical implications. It also analyses the interconnection between humans and cyberspace in the context of people’s natural proclivity towards truth, understanding of humanity and freedom. In the film’s most famous scene, the main character, Neo, played by Keanu Reeves, is offered two pills. He’s told: ‘You take the bluepill… the story ends, you wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe. You take the redpill… you stay in Wonderland, and I show you how deep the rabbit hole goes.’ One pill, the bluepill, will keep him in his current reality, which is a simulation, and he will continue to live his life as he knows it, and the other pill, the redpill, will allow him to break out of this reality and enable him to see the truth. The implication is that this truth will be a painful awakening and that the bluepill is the easier pill to swallow. Nevertheless, we all resonate with that natural urge to choose the redpill, to find out the truth, no matter how tough the consequences may be. Most people instinctively don’t want to live a lie; we want to know the truth of a situation even if it hurts us. In TheMatrix, the truth is harsh. The world has changed beyond all recognition to a dystopian hellscape. But the film instils a message that even this, the bleakest of all situations, can still be overcome by humanity’s will to survive and live. Even in the harsh reality of TheMatrix, there is hope.

The ideological redpill and blackpill take their inspiration from xixTheMatrixonly in the sense that they play off the allure of finding the ‘hidden truth’ to life and to see who, or what, is really pulling the strings in society. It’s important to note that while the overarching feeling of these groups is that feminism, leftism, ‘globalism’ or women are to blame for men’s current grievances, the people who subscribe to these groups and ideologies often have their own interpretations and there is not always agreement. It’s not a ‘one size fits all’ and these groups are prone to infighting. People in these communities also vary in their agendas and many fluctuate in their beliefs. There is no singular manifesto, book or influencer that is the definitive interpretation of these ideologies, and while we can make general assessments of these ideologies and beliefs, there will never be a full consensus. Due to this, even though I have researched the blackpill intensively over the past five years, there will be incels and others who will reject some of the claims made in this book, and due to word count limitations, there will be aspects of the ideology and community that will also be left out.

This book is not attempting to argue that the blackpill is correct; it aims to show how the seeds of truth in the blackpill stem from mainstream messages about gender, physical appearance and society. We are all blackpilled to an extent, we just may not recognise it. That’s not to say that these messages are correct or good either, and that is important to note. Most of the messages that this book will detail are harmful, misogynistic and unhealthy.

The basis of this book is threefold:

To bring an understanding of the incel worldview, the blackpill, to people through the medium of film and media.To show how many blackpill ideas fit neatly into messaging already shown in mainstream media.xxTo show how the blackpill can lead to extremism, dehumanisation and violence against the self and others.By understanding the worldview, we can have better conversations with incels, whether that be online or in person. It can help us to see where they’re coming from, why they’re feeling the way they are and how we can try to open lines of communication to bring them back into the fold. Incels do inherently want to come back in; they want to have friends, make connections and be accepted. Some may be further down the path than others and some may have deep-rooted issues that make it difficult to connect. But ultimately, the consistent cure to isolation and hate is connection.

I interviewed thirty-two incels over the course of my research for this book who all agreed to share their answers as long as I didn’t use their online usernames. These were individuals I found through X (formerly Twitter), many of whom I had been in contact with prior to this project. They varied in location – the majority are from the US and the UK, but other countries include Canada, France, Italy, Australia and New Zealand. They also ranged in age, with the average age being twenty-four to twenty-five, the youngest being nineteen and the oldest in their mid-thirties. There was also variations in socio-economic backgrounds, locations (rural and urban), careers and life situations.

The majority of these incels identify as non-misogynistic. There may be confusion over the difference between non-misogynistic and misogynistic incels, which is understandable. There are no exact clear lines between the two, except that non-misogynistic incels will tell you that they don’t hate or blame women, while extremist and misogynistic incels will be clear that they do. There are also many who vacillate between the two labels and who might adopt more xxihateful narratives when they’re in low moods but who will revert back when they feel better. Non-misogynistic incels are more open to talk to women as friends, colleagues or, in my situation, as a researcher and general acquaintance. Misogynistic incels are much more resistant to talk to women and are more likely to harass and insult them online. It can be confusing, however, as I’ve experienced receiving a combative or insulting reply to a post of mine publicly only to later receive a private message from that person hoping to talk to me about the post in a much more respectful way. In those cases, it appears as if they’re posturing to other incels and people publicly by showing that they aren’t afraid to confront women (me) while simultaneously being interested in having a real conversation.

Some of the non-misogynistic incels I interviewed for this book did share misogynistic views and used slurs during the interviews. Words such as ‘foid’, a common term which is an amalgamation of the words ‘female’ and ‘android’, as in robots, occur in some of the quotes. None of the incels interviewed claim to support violence, harassment or any form of direct threat or intimidation. Not all of the incels gave me answers on every topic covered. These individuals do not necessarily represent the views of all incels and most of them don’t represent the views of extremist misogynistic incels. However, all of them are well acquainted with the blackpill and the online incel community, and the majority of them are blackpilled to a degree and self-identified to me as incels. Two interviewees are not strictly incels but resonated with the incel experience. For transparency, I am not able to trace and check the validity of their ‘incel status’, so I cannot vouch for certain that they were all completely upfront about their issues with relationships, or their involvement with the blackpill, but judging from their answers and online presence, I do trust their authenticity.

xxiiIn order to provide balance and be representative of the wide variety of incels and to further this ethnographic research, I have also peppered the text with quotes from the largest incel forum, to show the opinions and views of more extremist and misogynistic incels.

Some of the views and narratives in this book are intense, hateful and heavy. Incels are not a monolith, and while many may not support violence or go on to commit violence, it is important to hear from the ones who do see violence and other forms of extremist actions as legitimate.

Most people don’t become extremists, even if they share many of the vulnerabilities we see in those who do. The fact that this is true should keep us sleeping soundly at night. However, for those people that do succumb to hatred, why is it that we so quickly lose our empathy for these prodigal sons and daughters? As the famous primatologist Jane Goodall says: ‘Only if we understand, can we care. Only if we care, we will help. Only if we help, we shall be saved.’2 The films and TV shows discussed in this book can provide us with a Rosetta Stone to help better understand incels, not to excuse their actions and beliefs but to bridge the gap between them and us and provide honest reciprocal understanding.

NOTES

1 Rebecca de Leeuw and Sophie H. Janicke, ‘How Movies Can Help Children Find Meaning in Life’, Greater Good Science Center, 26 September 2023, https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_movies_can_help_children_find_meaning_in_life.

2 Jane Goodall, quoted in Jennifer Lindsey, JaneGoodall:40YearsatGombe(Stewart, Tabori & Chang Inc., 1999).

PART ONE

INCELS 101

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, there was a planet inhabited by a peculiar species. Although intelligent, this species relied on a rigid societal hierarchy. One half of this species, the males, had to be big, strong, dominant, adventurous, acquisitive, competitive, sexually confident and brave. The other half of the species, the females, were conditioned to be beautiful, nurturing, obedient, sexually submissive and emotionally sensitive. The males who displayed their allocated traits the best were at the top of the social totem pole, especially if they also had physical attributes that contributed to these traits, such as strong jawlines, huge muscles and were large in stature. Females who excelled at their given traits were just below on the social ladder. Females were also viewed as prizes; they were the muses for the males and the main caretakers of infants.

The males were taught to compete against each other while also continually aiming to seek each other’s approval. This type of competition meant that to maintain the status quo, the males needed to live in emotional isolation and cultivate a life predicated on stoic individualism. Their internal alliances were tempered by the main 2rule that they were forbidden from being too much like the females, physically and behaviourally. Alliances with females were almost non-existent, except in those relationships based on duty, conquest and reproduction.

Messages exemplifying this societal order could be found everywhere, from advertisements to politics, to fiction, to sports, to everyday conversation. Entire industries were established around physical beauty, which were mostly aimed towards the females. The places of work and politics had cultivated climates where the traits associated with male behaviour were lionised. This gendered social hierarchy prevailed through continuous reinforcement, which was so ubiquitous and embedded in the social fabric that most of the species didn’t even question it. And as the planet achieved new technological advancements, these insistently gendering messages were beamed into homes all day, every day through new electronic devices.

However, while this planet was home to the top males and females and plenty of others that fell somewhere in the middle, there were also those who had fallen to the bottom of the hierarchy. These were the individuals who were unable to fit in and live up to their established gender roles. This planet revolved around winners and losers and life depended on how well you matched the description of your sex, and while diversity was outwardly celebrated, deviation from the norm was widely punished with mockery and exclusion.

This is the world that incels come from and a world most of us might recognise too.

As this book primarily discusses how the incel worldview is shaped by stories told through the media, it seems fitting to start with the origin story of the incel community itself – and how I came across it.

CHAPTER ONE

THE INCEL LORE

The first time I clicked on an incel forum, I felt like I was stepping into a twisted version of Alice’s Wonderland. I couldn’t understand anything – the words, the pictures, the jokes, the memes. It was all so alien, and I had no Rosetta Stone to guide me. There were so many phrases I had never seen before. Words that referred to women, ethnicity, race and sexuality littered every comment and post, each of them so creatively vile that they would make anyone with even a shred of decency close their laptop and purge the experience from their memories. Even without fully understanding each term, it’s easy to see the visceral disgust and hate that radiates from each newly invented slur until it becomes almost impossible to see anything except overt, extreme and borderline psychotic hatred. Just to give a little example of the type of posts on these extreme forums:

Some baseball fag worth 50 million slept with an ugly fakeup ridden 5/10 beckywhore and lo and behold he was accused of sexual battery and dropped from his team, the Dodgers. Of course, this was all done without evidence because América is a 4gynocentric dystopia that believes all women even though lying is women’s nature and this whore had every incentive to lie.1

Aside from the obvious hate, this post shows just how confusing some of these messages are because it’s not clear if the poster is sympathetic to this baseball player or not. Sure, he’s definitely blaming the woman at the centre of the story for this situation and bemoaning what he deems as a ‘gynocentric dystopia’, but he also begins by referring to the baseball player with a homophobic slur (just before going on to talk about a sexual liaison he had with a woman, which in itself is quite confusing). This is the world of incel forums: nothing is ever quite so simple.

Underneath the layers of hate and rage is an oppressive nihilism that permeates the forums like an ever-present current in a cyber-River Styx. Posts about giving up, depression, loneliness and suicide flood the screen, making these places full of not only extreme hatred but also extreme despair. Most internet tourists who find themselves on incel spaces stay for only a brief visit. After a quick look around, they rapidly find the exit and chalk it all up to just another cursed part of the internet populated by the dangerous and insane. Some even view these spaces as a kind of virtual quarantine zone, where we keep infected, lost souls.

When I started working on extremism, I never wanted to spend much time researching incels. I was interested in neo-Nazis, new far-right conspiracy cults like QAnon and modern militia-type extremist groups, such as the Proud Boys. During a time when I was volunteering for Life After Hate, a US organisation dedicated to helping people leave the violent far right, I was asked to draw up a series of factsheets on newer forms of extremism and extremist movements. It was this activity that first meaningfully introduced me to the incels. By then, I was used to reading extreme rhetoric. I had researched 5the Proud Boys the previous year and reading vile things being said about people, especially women, had become a normal day for me and didn’t affect me much any more. Yet even with that experience, something about the incel forums was too much, too heavy, too dark. I was glad to submit that factsheet and move on. However, life had other ideas, and only a couple of months later, I was asked if I would do it again for a project for another organisation, Groundswell Project UK. It really does feel like we often don’t get to choose where we end up, a sentiment I think would resonate with incels themselves. It’s also funny how sometimes it’s in things you least expect that you can find the most intrigue and meaning. That was me with incels.

My first challenge was to try to understand the lingua franca of incels. Incel forums are so permeated with in-group concepts and language that this would require a significant amount of time, starting with the word ‘incel’ itself. Incel is a portmanteau of the words ‘involuntary celibate’, but this seemingly obvious meaning isn’t comprehensive, because in the incel world, like in Wonderland, nothing is ever truly as it seems. Tracing the origin of the word led me to discover the history of the whole phenomenon, the incel lore. As with any other myth, the incel lore includes many different arcs, significant people and events, places and transformations. As with every movement and community, incel groups didn’t emerge from a vacuum or even fall out of a coconut tree.

It Began with 4chan

The idea of involuntary celibacy originated in the 1990s when it was coined by a young woman named Alana as ‘invcel’ (notice that early ‘v’). Alana was a young Canadian university student who began a 6website called Alana’s Involuntary Celibacy Project, which was open to anyone who could empathise with the feeling of romantic loneliness, including women and members of the LGBTQ+ community.2 The term then largely disappeared for some years until it experienced a virtual renaissance around 2008 with the newly developed /r9k/ messaging board on 4chan, an anonymous website where people can post and discuss images. The /r9k/ board was a forum frequented by those who were on very familiar terms with the internet. They were mostly young and mostly male. The board was originally created as a kind of virtual experiment to ensure and enforce originality in posts and comments. The /r9k/ forum was situated on the notorious website 4chan, which has a reputation for being the lowest cesspool on the internet and the home of edgy teenagers, neo-Nazis, school shooter groupies, misogynists, homophobes, transphobes and other such groups. Though, 4chan wasn’t initially intended to be the internet’s wasteland: it was originally created to be an image-sharing board with little moderation and with a slightly left-wing and anarchic spirit. It was even the birthplace of the famous hacktivist group Anonymous.3

In the mid- to late 2000s, however, 4chan found itself prey to the online far right and became a hotbed of white supremacist and similar extremist content. Its association with violence, neo-Nazism and hate grew while 4chan attempted to maintain its original intention to act as a general, left-leaning forum dedicated to free speech. Ultimately, the website’s culture swung to the extreme right and posts became laced with antisemitism, misogyny and homophobia and promoted white supremacy and other far-right talking points. Today, it still hosts several boards where people can discuss anything from origami collecting to Holocaust denial, all within a culture of overt vitriol and anonymity.7

In the late 2000s, there was also something else brewing on 4chan: a nihilism predicated on loneliness, rejection, depression and despair started to seep through and manifest itself in memes such as ‘Forever Alone’. These memes acted as a pressure valve for general teenage angst. Among the hate, 4chan also accidentally became a sort of unofficial support group for lonely teenage boys and young men. Although the graphics and drawings were intentionally unsophisticated and crude, even childlike, the concepts they explored were emotional, cathartic and often painful. Most of the more popular posts were about romantic relationships, solitude, loneliness and the crushing and overwhelming chaos and uncertainty of life.

Anexampleofthe‘ForeverAlone’seriesofmemes

The memes were laden with sarcasm, irony and overtly zany or ridiculous humour. This allowed users to relate to and repost them 8without feeling the vulnerability attached to confessing deep insecurities and fears. Over on /r9k/, users quickly realised that posting about their personal lives, especially when the anecdotes were darker or more depressing, both met the board’s criteria for originality and garnered hits. The board essentially became a massive public confessional for its users, who were mostly young men. The anonymity enabled them to express vulnerability and describe emotional situations, while the meme-ification of the posts meant that they also had a style guide to follow. They copied words and phrases from each other to describe their circumstances and feelings, eventually creating a lexicon and in-group culture based around shared experiences and tied together with specific language.

Andrew, an American in his early twenties, told me he spent a lot of time in his teenage years scrolling /r9k/: ‘It was the board I ended up spending the most time on because I liked the whole outsider thing.’ On how he felt about the emotional intensity of the posts, he said that there was a culture on /r9k/ that compelled users to make extreme and performative posts for attention but that he felt a lot of the stories were genuine. ‘There was definitely a bit of the diary posting but also the format of 4chan encourages people to post the most intense stuff they can to get replies … A lot of it felt very provocative to me but there was definitely some real stuff mixed in.’

The problem with /r9k/, like the problem with all unmoderated forums online where people relay their deepest and darkest insecurities and experiences, was that there was not a lot of incentive, or expertise, to offer helpful support. The users related to each other’s experiences because they were all undergoing similar situations, but they hadn’t yet found a way out of them; it was the blind leading the blind. A climate of catastrophising and nihilism took hold and 9the frequency of likeminded posts without hopeful updates corroborated users’ fears that their situations would be long-lasting, if not permanent. This was simply life, and life was suffering, at least for the unlucky ones who found themselves on /r9k/. Andrew told me that even though he had never joined one, there were some instances where people would host Skype calls to end their lives.

Before long, the culture and content of /r9k/ began to stabilise. Ironically, for a board designed to engender originality and uniqueness (it was moderated by a robot programmed to delete repetitive posts), the content began to centre on obvious, recurring themes. Most posts centred mainly around girls, loneliness and virginity. A theory as to why this occurred is that it was due to 4chan’s young, male userbase, many of whom also had issues relating to neurodiversity, employment, social anxiety, romantic relationships and general social skills. The fact that /r9k/ became a board where users wanted to discuss their insecurities around talking to girls, dating and sex was inevitable. The board even developed its own community. Users would return and post over and over again, reply to each other and have long conversations on threads. They also began to create and use specific terms and phrases: ‘Chads’ referred to attractive men, ‘normies’ meant most men who had partners and ‘roasties’ was a misogynistic term for sexually active women.

Users even made up a term for themselves, ‘robots’, which referred to the robot moderator of the forum but also to their feeling of being less than human due to their inability to access romantic love or affection. The board ultimately became more extreme, inundated by pure sexual frustration, rage, resentment and depression, and so, in turn, the posts became more and more dramatic, performative, misogynistic and nihilistic. Women became demonised and the enemy, along with Chad and the normies too. Bonds were 10forged between users, not necessarily on a one-to-one level but in the form of a group identity or community. It became a society of confirmed outcasts, as sure about their fate and situation as they were resentful of it. The original catharsis provided by the posts had morphed into quasi-oaths of allegiance to the group. There was a surrender of optimism and hope in return for intellectual verification that they were correct, that they knew the bleak, nihilistic truth and the unchangeable nature of their situation.

Examples of /r9k/ posts

Today, incel forums still embody this culture, originating on /r9k/, where rampant hostility is the modus operandi, not just hostility towards society but also to each other and themselves.13

Where the Incels Go

Think about the internet like a really, really big city, where everyone has their usual ‘spots’ where they like to go and hang out. Some people like to chill out over at TikTok, zoning out without interacting much; others prefer to chat with huge groups of internet friends over at Discord; others like to get riled up about political and social issues with strangers on Facebook and X (formerly Twitter); and then you’ll find others just flitting around fashion forums, mum’s forums, fitness forums, movie forums, you name it, the internet has it. Like everyone else, incels also have their go-to spots which other people frequent, but they’ve also carved out their own little hideaways (that are often not so hidden away).

As /r9k/ grew, it seemed clear that there was a demand for places where people could post about their difficult dating situations, depression and loneliness, so, as expected, soon came along dedicated incel sites. Dedicated incel forums vary from overtly hateful to spaces that are based on practical support and advice. They also vary on who they let in: some spaces allow women and LGBTQ+ folks, but others are strictly for heterosexual men. The ages also differ, with some forums having members who are in their thirties and above, while other forums are explicitly youth coded. The lingo and topics often change according to each forum or space; the forums on dedicated sites are a lot more seeped in nihilism, hate and misogyny, while others which are found on more mainstream sites, such as Reddit, are more moderated.

The incel forums most people point to when describing the virulent misogyny that incels are associated with are independent websites which are culturally inspired by /r9k/. These forums are often difficult to look at as they contain violence, hate, suicide, aggression, 14support for sexual violence and even instances of support for paedophilia and other forms of abuse. These forums revolve around US free speech laws, where nearly anything goes except for explicit threats of violence and posting child pornography. The forums are mostly used by young men, aged between sixteen and twenty-five, who engage with each other under anonymous usernames and profile pictures in the same way users do on 4chan.

Incel forums are often banned on mainstream sites due to overt misogyny and other hateful content. However, some forums that are built on non-hateful support and advice are still allowed. For example, r/IncelExit and r/ForeverAlone are two forums that are still active on one of the largest, mainstream forums, Reddit, as of writing this book. r/IncelExit is a forum dedicated to helping people leave the incel ideology and has 20,000 members. It’s an active forum where men who identify as incels seek out advice from former incels and non-incels alike on how to get out of nihilistic and/or hateful thinking. The forum is a quasi-support and dating advice group where users try to help each other by giving tips on what they feel works to date, make friends and leave behind negative thinking. It’s a landing pad for many incels who want to leave behind the more extremist spaces and get their lives on track. However, it does come with pitfalls. It doesn’t provide ongoing, individual support and as its users are basically ordinary people who are volunteering to help others – there isn’t a lot of evidence-based or therapeutic advice available. But it’s still a much more supportive and generally wholesome space than the extremist incel forums, and it can show incels that there are people out there who care, which is a good start to helping people leave behind an ideology based on nihilism, loneliness, alienation and resentment.

Extremist incel spaces do appear to be popular and active, as the 15various forums have accumulated thousands of members and there are new posts made every day. Incel spaces and content have also migrated into more mainstream sites, such as YouTube, TikTok and X, where incels interact with both each other and non-incels. Even in these mainstream spaces, a lot of the lingo and culture of /r9k/ and extreme incel websites are present but just tamped down to keep users from getting banned by the site’s moderators.

Even when incel spaces are on mainstream sites, like TikTok or X, they still end up being pretty insular. Incel users mostly just talk to each other and often create private groups or spaces. This tends to defeat the purpose of being on these mainstream platforms, as they’re still cordoning themselves off. I think the reason these users prefer to have these insular spaces on mainstream platforms, as opposed to using the dedicated incel forums, is because they’re put off by the intensity and overt hate of these spaces. On the flipside, some incels may use mainstream platforms because they enjoy spreading hate to non-incels (normies) and baiting others (known online as trolling). And others seem to want to make connections in both the incel world and the outside world – they want to talk to the ‘normies’, perhaps even form connections, while maintaining a counter-intuitive resentment towards them. This book will show that inside the incel community, there is a lot of variation of beliefs and ideas as well as different levels of extremism – there are many types of inhabitants in the incel world.

Along Came a Gamer

Online, life moves faster and moments and notable events, people and places come and go like shifting sands. Viral videos that garner 16millions of views become vague memories within a month; popular influencers fall in and out of favour (think David Dobrik, Jenna Marbles or Shane Dawson). Even entire social media sites that once seemed like steadfast pillars of the internet eventually sing their swansong (RIP Myspace and Vine). Very little that happens online has a memorable long-lasting impact or stays relevant a decade or more later, so when an event occurs that is so large that it causes genuine and enduring cultural change on the internet, it’s noteworthy in a Halley’s Comet kind of way. In 2014, an event just like this occurred that would change the course of internet culture for ever, and it happened at a time when not only the internet was changing but so was the world outside it.

Gamergate was a complicated series of events rooted in a campaign of mass harassment against women in the video-gaming world and industry and most notably three specific women: Brianna Wu, Anita Sarkeesian and Zoë Quinn (who has since come out as non-cisgender but at the time used she/her pronouns). The story began when a video-game designer who was Quinn’s ex-boyfriend made a post on a forum called ‘Something Awful’. The post was a story of deceit and betrayal in their short-lived relationship. It was quickly deleted on the forum but not before it was copied and immortalised on 4chan. The story rapidly gained traction as it not only divulged personal, salacious and overly dramatic details of a relationship gone sour but also of accusations of quid pro quo in the gaming industry, with sexual favours allegedly being traded in return for positive reviews by gaming journalists. Then, in came actor Adam Baldwin – known primarily for his role on the sci-fi Western TV show Firefly(2002–2003) – who, for reasons unknown, decided this was a great opportunity to engineer a mass movement and was the first person to coin the hashtag #Gamergate.4 After 17him entered Steve Bannon and Milo Yiannopoulos, who ran with it and garnered attention to it through the right-wing news site Breitbart.5

Beyond the original post, there was no proof that Quinn had made any kind of deals for favourable reviews and the person she was alleged to have made the arrangement with never even wrote a review for her game, DepressionQuest.6 It didn’t matter, though. It was too late: facts got lost in fiction and what began as the story of one woman in the gaming world snowballed into something far beyond her, an angry ex-boyfriend or any reviewer. Rick, Humphrey Bogart’s character in Casablanca(1942), famously said: ‘The problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world.’ Well, so much for that, it seems.7

From this one post arose an all-out online war led by angry gamers who claimed that the Quinn situation was the gaming equivalent of the canary in the coalmine signalling that feminism had gone too far. These people insisted that women, like Sarkeesian with her critiques of female representation in games, were unjustly encroaching on gaming spaces and unnecessarily criticising them while simultaneously using their feminine wiles to sleep their way to the top of the gaming industry. The Gamergate scandal was publicised in media from the NewYorkTimes8 to TheGuardian9 and established journalists, including Ezra Klein, also weighed in on the situation.10

There has been much dispute as to who the individuals that instigated Gamergate were, and although it was originally viewed as a conservative, right-wing backlash, research has since shown that many of the participants considered themselves liberal (in the American sense of the word).11 Some academics and journalists have even cautioned against viewing the Gamergate movement as purely 18misogynistic. Instead, they advocate for viewing it as a cluster of simultaneous events involving a variety of people with different agendas, including some who had personal grievances against Quinn, Sarkeesian and Wu and wanted to exact revenge; some who just didn’t like women and were antifeminist; some who didn’t believe that the gaming world was misogynistic, a group which included women; and finally, some who saw themselves as defending video-game ethics. The controversy grew to such an extent that people began to feel frustrated more by how they were being perceived by others than the concerns which brought them there in the first place. A feeling of ‘my side is my team’ took over and even the bad elements of each side were almost ignored or downplayed to maintain ideological purity. The confusion over who each side was and what they were fighting for by the media and those who opposed the Gamergate movement led some originally non-misogynistic Gamergate supporters to harden in their views against liberalism and so-called social justice warriors (SJWs). Ezra Klein highlighted:

It’s worth stopping for a moment to say that Gamergate, as well as the reaction against it, isn’t any one thing. It includes horrifying, probably criminal, harassment against pretty much any women who dare oppose it. It’s partly an argument about what kinds of games the gaming press should cover – and, by extension, what kinds of games developers should make. It has members who want clearer disclosure policies in gaming journalism. It has a lot of people who joined because they hate feminism and internet ‘social justice’ warriors. And it has many people, on both sides, who are far surer about who they’re fighting than what they’re fighting about.1219

Monetising Misogyny

However you want to describe it, Gamergate was the beginning of the internet’s misogyny arc, the moment when it became clear that there was an appetite for rallying an online crowd to oppose gender discourse in a salacious, aggressive and cruel manner. This shift was the spark that motivated media-savvy grifters, from Steve Bannon to Gavin McInnes and, later, Andrew Tate, to manipulate the turning tide and capture large online audiences.13 This accidental experiment also proved that the internet could be a space for genuine political and social movements that affect the offline world. The internet was now seen as a place where hearts and minds could be won, groups could be created, power could be accumulated and money could be made.

Gamergate took the internet by storm and led to an intense backlash. Suddenly, videos about antifeminism started to gain traction with clickbait titles like ‘Feminist Destroyed’ and many subcultures that were specifically ‘anti-social justice warriors’ and ‘antifeminist’ cropped up. One of the largest which grew in membership and traction was the notorious Reddit forum r/TheRedPill, created in 2012, which revolved around promoting tactics to manipulate women into sex. Nuance became lost in the tornado of content. The content promoted was extreme, intense and emotional, and the backlash against it equally so. Many people were caught in the crossfire of the culture wars and often took sides when they felt personally victimised or misrepresented, because as every emo album from the early 2000s demonstrated, no one likes to feel misunderstood.

A gap arose in the market for content that appealed to a sense of 20feeling unfairly judged for having a critical view on issues related to ‘leftism’, feminism, diversity hiring, sensitivity training in workplaces and affirmative action and so on.14 Online, this content was positioned as ‘taboo’, ‘controversial’ and ‘anti-establishment’ and allowed people to pass through seamlessly into the realm of the ‘altlite’15 (the term given to the lighter version of the extremist right-wing ‘alt-right’; the newer, digital manifestation of the far right). Influencers who straddled the camps of ‘feminism has gone too far’, ‘the world is too full of SJW snowflakes’ and ‘you can’t say anything any more; free speech is under threat’ began to create a seemingly edgy yet ‘common sense’ ideology that quickly garnered popularity.

Bland and strait-laced middle-aged men and college professors suddenly became the equivalent of rockstars. Men like Jordan Peterson, Ben Shapiro, Sam Harris and Gavin McInnes became the icons of ‘alt’ (alternative) and ‘taboo’ as they appeared to take a radical stand against the seemingly overarching and oppressive forces of feminism, leftism and ‘cultural Marxism’. Instead of stereotypical rockstar behaviour, cool and rebellious became ‘making your bed’ (a now famous Jordan Peterson mantra). Shortly after, the self-proclaimed political outsider Donald Trump was elected as President, much to the satisfaction of certain 4chan users and other online forums.

A lot of these sentiments did not necessarily stem from a careful consideration of the nature of politics, society and humanity but as a reaction to what appeared to be the growing prominence of ‘cancel culture’, the #MeToo movement, Black Lives Matter and a general social ennui related to increased atomisation and loneliness. People were angry and frustrated and charismatic influencers and politicians saw an opportunity. The Information Age represented something of a gold rush and Gamergate was the canary in that goldmine.21

A 2016 Gamergate meme based on The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch