26,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Film Directors in America

- Sprache: Englisch

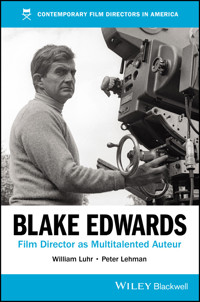

BLAKE EDWARDS

Blake Edwards: Film Director as Multitalented Auteur is the first critical analysis to focus on the dramatic works of Blake Edwards. Best known for successful comedies such as The Pink Panther series with Peter Sellers, Blake Edwards wrote, produced, and directed serious works in radio, television, film, and theater for seven decades. Although hit films such as Breakfast at Tiffany’s and ‘10’ remain popular, many of Edwards’s dramas have been forgotten or marginalized.

In this unique book, William Luhr and Peter Lehman draw on original research from numerous set visits and personal interviews with Edwards and many of his creative and business collaborators to explore his dramas, radio and television work, theatrical productions, one-man art shows, and unproduced screenplays. In-depth chapters analyze non-comedic films including Experiment in Terror, Days of Wine and Roses, and The Tamarind Seed, the theatrical feature film Gunn and the made-for-television film Peter Gunn, the musical adaptation of Victor/Victoria, and lesser-known films written but not directed by Edwards, such as Drive a Crooked Road.

Throughout the book, the authors apply contemporary film theory to auteur criticism of different works while sharing original insights into how Edwards worked creatively in disparate genres and media using composition, editing, sound, and visual motifs to shape his films and radio and television series.

A one-of-a-kind examination of one of the most influential film directors of his generation, Blake Edwards: Film Director as Multitalented Auteur is an excellent supplementary text for university courses in American cinema, genres, auteurs, and film criticism, and a must-read for critics, scholars, and general readers interested in the works of Blake Edwards.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 570

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Contemporary Film Directors in America

Series Editors: Peter Lehman (Arizona State University, USA) and William Luhr (Saint Peter’s University, USA)

The Contemporary Film Directors in America series focuses on recent and current film directors within the contexts of globalization and the convergence of the entertainment and technology industries. The definition of “American” includes film directors who have worked in America and with American production companies, regardless of citizenship, and the series considers hyphenate directors who are also writers and producers working in multiple media forms including radio, television, and film.

Blake Edwards: Film Director as Multitalented Auteur

William Luhr and Peter Lehman

Blake Edwards

Film Director as Multitalented Auteur

William Luhr and Peter Lehman

This edition first published 2023

© 2023 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by law. Advice on how to obtain permission to reuse material from this title is available at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

The right of William Luhr and Peter Lehman to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with law.

Registered Offices

John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, customer services, and more information about Wiley products visit us at www.wiley.com.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some content that appears in standard print versions of this book may not be available in other formats.

Trademarks: Wiley and the Wiley logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty

While the publisher and authors have used their best efforts in preparing this work, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives, written sales materials or promotional statements for this work. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a specialist where appropriate. The fact that an organization, website, or product is referred to in this work as a citation and/or potential source of further information does not mean that the publisher and authors endorse the information or services the organization, website, or product may provide or recommendations it may make. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Paperback ISBN: 9781119602040; ePub ISBN: 9781119602064; ePDF ISBN: 9781119602057

Cover Image: © Ron Galella/Contributor/Getty Images

Cover design by Wiley

Set in 10.5/13pt STIXTwoText by Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd, Pondicherry, India

From William Luhr

For Judy and David, with love and gratitude

From Peter Lehman

For Melanie, again and forever

Contents

Cover

Series Page

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

List of Figures

Preface

Acknowledgments

CHAPTER 1 Introduction: “Call Me Blake.”

CHAPTER 2 The Early Period (1948–1962)

CHAPTER 3 Mister Cory (1957

CHAPTER 4 Experiment in Terror (1962)

CHAPTER 5 Days of Wine and Roses (1962)

CHAPTER 6 Gunn (1967) and Peter Gunn (1989)

CHAPTER 7 Wild Rovers (1971)

CHAPTER 8 The Carey Treatment (1972)

CHAPTER 9 Julie (1972)

CHAPTER 10 The Tamarind Seed (1974)

CHAPTER 11 Sunset (1988)

CHAPTER 12 The Late Period: Play It Again, Blake

Appendix 1: Books on Blake Edwards

Appendix 2: The Interviews

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Illustrations

CHAPTER 01

FIGURE 1.1

A Fine Mess,

© 1986 Columbia...

FIGURE 1.2

Sunset,

© 1988 Tri-Star.

CHAPTER 02

FIGURE 2.1

Panhandle,

© 1948 Monogram.

FIGURE 2.2

Panhandle,

© 1948 Monogram.

FIGURE 2.3

Panhandle,

© 1948 Monogram.

FIGURE 2.4

Panhandle,

© 1948 Monogram.

FIGURE 2.5

Panhandle,

© 1948 Monogram.

FIGURE 2.6

Strangler of the Swamp,

© 1946...

FIGURE 2.7

Strangler of the Swamp,

© 1946...

FIGURE 2.8

Strangler of the Swamp,

© 1946...

FIGURE 2.9

Leather Gloves,

© 1948 Columbia...

FIGURE 2.10

Leather Gloves,

© 1948 Columbia...

FIGURE 2.11

Leather Gloves,

© 1948 Columbia...

FIGURE 2.12

Drive a Crooked Road,

© 1954 Columbia...

FIGURE 2.13

Drive a Crooked Road,

© 1954 Columbia...

FIGURE 2.14

Drive a Crooked Road,

© 1954 Columbia...

FIGURE 2.15

Drive a Crooked Road,

© 1954 Columbia...

FIGURE 2.16

Drive a Crooked Road,

© 1954 Columbia...

FIGURE 2.17

Drive a Crooked Road,

© 1954 Columbia...

FIGURE 2.18

Drive a Crooked Road,

© 1954 Columbia...

FIGURE 2.19

Drive a Crooked Road,

© 1954 Columbia...

FIGURE 2.20

The Atomic Kid,

© 1954 Republic Productions...

FIGURE 2.21

The Atomic Kid,

© 1954 Republic Productions...

FIGURE 2.22

The Atomic Kid,

© 1954 Republic Productions...

FIGURE 2.23

The Atomic Kid,

© 1954 Republic Productions...

FIGURE 2.24

The Atomic Kid,

© 1954 Republic Productions...

FIGURE 2.25

The Atomic Kid,

© 1954 Republic Productions...

FIGURE 2.26

My Sister Eileen,

© 1955 Columbia...

FIGURE 2.27

My Sister Eileen,

© 1955 Columbia...

FIGURE 2.28

My Sister Eileen,

© 1955 Columbia...

FIGURE 2.29

My Sister Eileen,

© 1955 Columbia...

FIGURE 2.30

My Sister Eileen,

© 1955 Columbia...

FIGURE 2.31

The Couch,

© 1962 Warner Bros. Entertainment...

FIGURE 2.32

The Couch,

© 1962 Warner Bros. Entertainment...

FIGURE 2.33

The Couch,

© 1962 Warner Bros. Entertainment...

CHAPTER 03

FIGURE 3.1

Mister Cory,

© 1957 Universal-International.

FIGURE 3.2

Mister Cory,

© 1957 Universal-International.

FIGURE 3.3

Mister Cory,

© 1957 Universal-International.

FIGURE 3.4

Mister Cory,

© 1957 Universal-International.

FIGURE 3.5

Mister Cory,

© 1957 Universal-International.

CHAPTER 04

FIGURE 4.1

Experiment in Terror,

© 1962 Columbia...

FIGURE 4.2

Experiment in Terror,

© 1962 Columbia...

FIGURE 4.3

Experiment in Terror,

© 1962 Columbia...

FIGURE 4.4

Experiment in Terror,

© 1962 Columbia...

FIGURE 4.5

Experiment in Terror,

© 1962 Columbia...

CHAPTER 05

FIGURE 5.1

Days of Wine and Roses,

© 1962 Warner...

FIGURE 5.2

Days of Wine and Roses,

© 1962 Warner...

FIGURE 5.3

Days of Wine and Roses,

© 1962 Warner...

FIGURE 5.4

Days of Wine and Roses,

© 1962 Warner...

CHAPTER 06

FIGURE 6.1

Gunn,

© 1967 Paramount Pictures...

FIGURE 6.2

Gunn,

© 1967 Paramount Pictures...

FIGURE 6.3

Gunn,

© 1967 Paramount Pictures...

FIGURE 6.4

Peter Gunn,

© 1989 New World Television.

FIGURE 6.5

Peter Gunn,

© 1958 Spartan Productions...

FIGURE 6.6

Peter Gunn,

© 1989 New World Television.

CHAPTER 07

FIGURE 7.1

Gunn,

© 1967 Paramount Pictures Corporation.

FIGURE 7.2

Gunn,

© 1967 Paramount Pictures Corporation.

FIGURE 7.3

Wild Rovers,

© 1971 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

FIGURE 7.4

Wild Rovers,

© 1971 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

FIGURE 7.5

Wild Rovers,

© 1971 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

FIGURE 7.6

Wild Rovers,

© 1971 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

FIGURE 7.7

Wild Rovers,

© 1971 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

FIGURE 7.8

Wild Rovers,

© 1971 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

FIGURE 7.9

Wild Rovers,

© 1971 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

FIGURE 7.10

Wild Rovers,

© 1971 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

FIGURE 7.11

Wild Rovers,

© 1971 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

CHAPTER 08

FIGURE 8.1

The Carey Treatment,

© 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

FIGURE 8.2

The Carey Treatment,

© 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

FIGURE 8.3

The Carey Treatment,

© 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

FIGURE 8.4

The Carey Treatment,

© 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

FIGURE 8.5

The Carey Treatment,

© 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

FIGURE 8.6

The Carey Treatment,

© 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

FIGURE 8.7

The Carey Treatment,

© 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

FIGURE 8.8

The Carey Treatment,

© 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

FIGURE 8.9

The Carey Treatment,

© 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

FIGURE 8.10

The Carey Treatment,

© 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

FIGURE 8.11

The Carey Treatment,

© 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

CHAPTER 09

FIGURE 9.1

Julie,

© 1972 Anjul Productions...

FIGURE 9.2

Julie,

© 1972 Anjul Productions...

FIGURE 9.3

Julie,

© 1972 Anjul Productions...

FIGURE 9.4

Julie,

© 1972 Anjul Productions...

FIGURE 9.5

Julie,

© 1972 Anjul Productions...

FIGURE 9.6

Julie,

© 1972 Anjul Productions...

CHAPTER 10

FIGURE 10.1

The Tamarind Seed,

© 1974 AVCO Embassy Pictures.

FIGURE 10.2

The Tamarind Seed,

© 1974 AVCO Embassy Pictures.

FIGURE 10.3

The Tamarind Seed,

© 1974 AVCO Embassy Pictures.

FIGURE 10.4

The Tamarind Seed,

© 1974 AVCO Embassy Pictures.

FIGURE 10.5

The Tamarind Seed,

© 1974 AVCO Embassy Pictures.

FIGURE 10.6

The Tamarind Seed,

© 1974 AVCO Embassy Pictures.

FIGURE 10.7

The Tamarind Seed,

© 1974 AVCO Embassy Pictures.

CHAPTER 11

FIGURE 11.1

Sunset,

© 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

FIGURE 11.2

Sunset,

© 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

FIGURE 11.3

Sunset,

© 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

FIGURE 11.4

Sunset,

© 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

FIGURE 11.5

Sunset,

© 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

FIGURE 11.6

Sunset,

© 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

FIGURE 11.7

Sunset,

© 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

FIGURE 11.8

Sunset,

© 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

FIGURE 11.9

Sunset,

© 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

FIGURE 11.10

Sunset,

© 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

FIGURE 11.11

Sunset,

© 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

FIGURE 11.12

Sunset,

© 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

FIGURE 11.13

Sunset,

© 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

FIGURE 11.14

Sunset,

© 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

FIGURE 11.15

Sunset,

© 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

CHAPTER 12

FIGURE 12.1 Victor/Victoria: The Original Broadway Cast...

Guide

Cover

Series Page

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Table of Contents

List of Figures

Preface

Acknowledgments

Begin Reading

Appendix 1: Books on Blake Edwards

Appendix 2: The Interviews

Index

End User License Agreement

Pages

i

ii

iii

iv

v

vi

vii

viii

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

List of Figures

1.1 A Fine Mess, © 1986 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

1.2 Sunset, © 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

2.1 Panhandle, © 1948 Monogram Pictures.

2.2 Panhandle, © 1948 Monogram Pictures.

2.3 Panhandle, © 1948 Monogram Pictures.

2.4 Panhandle, © 1948 Monogram Pictures.

2.5 Panhandle, © 1948 Monogram Pictures.

2.6 Strangler of the Swamp, © 1946 Producers Releasing Corporation (PRC).

2.7 Strangler of the Swamp, © 1946 Producers Releasing Corporation (PRC).

2.8 Strangler of the Swamp, © 1946 Producers Releasing Corporation (PRC).

2.9 Leather Gloves, © 1948 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

2.10 Leather Gloves, © 1948 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

2.11 Leather Gloves, © 1948 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

2.12 Drive a Crooked Road, © 1954 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

2.13 Drive a Crooked Road, © 1954 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

2.14 Drive a Crooked Road, © 1954 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

2.15 Drive a Crooked Road, © 1954 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

2.16 Drive a Crooked Road, © 1954 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

2.17 Drive a Crooked Road, © 1954 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

2.18 Drive a Crooked Road, © 1954 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

2.19 Drive a Crooked Road, © 1954 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

2.20 The Atomic Kid, © 1954 Republic Productions, Inc.

2.21 The Atomic Kid, © 1954 Republic Productions, Inc.

2.22 The Atomic Kid, © 1954 Republic Productions, Inc.

2.23 The Atomic Kid, © 1954 Republic Productions, Inc.

2.24 The Atomic Kid, © 1954 Republic Productions, Inc.

2.25 The Atomic Kid, © 1954 Republic Productions, Inc.

2.26 My Sister Eileen, © 1955 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

2.27 My Sister Eileen, © 1955 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

2.28 My Sister Eileen, © 1955 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

2.29 My Sister Eileen, © 1955 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

2.30 My Sister Eileen, © 1955 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

2.31 The Couch, © 1962 Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.

2.32 The Couch, © 1962 Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.

2.33 The Couch, © 1962 Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.

3.1 Mister Cory, © 1957 Universal-International Pictures.

3.2 Mister Cory, © 1957 Universal-International Pictures.

3.3 Mister Cory, © 1957 Universal-International Pictures.

3.4 Mister Cory, © 1957 Universal-International Pictures.

3.5 Mister Cory, © 1957 Universal-International Pictures.

4.1 Experiment in Terror, © 1962 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

4.2 Experiment in Terror, © 1962 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

4.3 Experiment in Terror, © 1962 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

4.4 Experiment in Terror, © 1962 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

4.5 Experiment in Terror, © 1962 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

5.1 Days of Wine and Roses, © 1962 Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.

5.2 Days of Wine and Roses, © 1962 Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.

5.3 Days of Wine and Roses, © 1962 Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.

5.4 Days of Wine and Roses, © 1962 Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.

6.1 Gunn, © 1967 Paramount Pictures Corporation.

6.2 Gunn, © 1967 Paramount Pictures Corporation.

6.3 Gunn, © 1967 Paramount Pictures Corporation.

6.4 Peter Gunn, © 1989 New World Television.

6.5 Peter Gunn, © 1958 Spartan Productions, Official Films, Inc.

6.6 Peter Gunn, © 1989 New World Television.

7.1 Gunn, © 1967 Paramount Pictures Corporation.

7.2 Gunn, © 1967 Paramount Pictures Corporation.

7.3 Wild Rovers, © 1971 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

7.4 Wild Rovers, © 1971 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

7.5 Wild Rovers, © 1971 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

7.6 Wild Rovers, © 1971 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

7.7 Wild Rovers, © 1971 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

7.8 Wild Rovers, © 1971 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

7.9 Wild Rovers, © 1971 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

7.10 Wild Rovers, © 1971 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

7.11 Wild Rovers, © 1971 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

8.1 The Carey Treatment, © 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

8.2 The Carey Treatment, © 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

8.3 The Carey Treatment, © 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

8.4 The Carey Treatment, © 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

8.5 The Carey Treatment, © 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

8.6 The Carey Treatment, © 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

8.7 The Carey Treatment, © 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

8.8 The Carey Treatment, © 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

8.9 The Carey Treatment, © 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

8.10 The Carey Treatment, © 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

8.11 The Carey Treatment, © 1972 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., Turner Entertainment Company.

9.1 Julie, © 1972 Anjul Productions, Inc.

9.2 Julie, © 1972 Anjul Productions, Inc.

9.3 Julie, © 1972 Anjul Productions, Inc.

9.4 Julie, © 1972 Anjul Productions, Inc.

9.5 Julie, © 1972 Anjul Productions, Inc.

9.6 Julie, © 1972 Anjul Productions, Inc.

10.1 The Tamarind Seed, © 1974 AVCO Embassy Pictures.

10.2 The Tamarind Seed, © 1974 AVCO Embassy Pictures.

10.3 The Tamarind Seed, © 1974 AVCO Embassy Pictures.

10.4 The Tamarind Seed, © 1974 AVCO Embassy Pictures.

10.5 The Tamarind Seed, © 1974 AVCO Embassy Pictures.

10.6 The Tamarind Seed, © 1974 AVCO Embassy Pictures.

10.7 The Tamarind Seed, © 1974 AVCO Embassy Pictures.

11.1 Sunset, © 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

11.2 Sunset, © 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

11.3 Sunset, © 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

11.4 Sunset, © 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

11.5 Sunset, © 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

11.6 Sunset, © 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

11.7 Sunset, © 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

11.8 Sunset, © 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

11.9 Sunset, © 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

11.10 Sunset, © 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

11.11 Sunset, © 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

11.12 Sunset, © 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

11.13 Sunset, © 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

11.14 Sunset, © 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

11.15 Sunset, © 1988 Tri-Star Pictures.

12.1 Victor/Victoria: The Original Broadway Cast Production, © 1995 Victor/Victoria Company.

Preface

We met Blake Edwards for the first time in 1979 to interview him in his suite at the Sherry Netherland Hotel in New York. It was the beginning of a relationship that would last 30 years. We last saw him at the invitational opening of what would be his final one-man art show in 2009. During those three decades, we visited his film and theater sets as well as his art exhibitions and did a number of interviews with him in his company offices in Hollywood as well as in his New York townhouse and his home in Brentwood. We also published our books Blake Edwards and Returning to the Scene: Blake Edwards, Volume 2. Both of those books were written while he was in mid-career and focused entirely on films that he directed. This book is our third and final one about that remarkable career. We did not draw upon our set visits in our first two books, saving them for this final volume, which covers his entire career. Like our previous books, this one is a critical analysis of his films, but we have also expanded it to cover films he wrote but didn’t direct and to include radio, television, theater, and art exhibitions. We use the interviews and our observations from watching him work only insofar as they shed light on his creative methods and mindset. This is not a biography, and we did not ask Blake or others about his personal life, though on a few occasions Blake brought up some issues he felt were relevant.

Since we quote from many unpublished conversations and interviews during our set visits, we have added an Appendix listing many of those we interviewed with the dates of the interviews. The interviews have all been transcribed and quotations from them are edited and accurate. When we have relied upon conversations that were not taped we summarize the point rather than quote it directly. Unless we were both present, we only use conversations that we documented with each other at the time.

A word about our publications. Everything we have each done throughout our long collaboration on this project and all our projects has been part of an equal co-author relationship. In that spirit, we have always rotated the order of our names between each article and also between each book. For example, our previous book, Thinking About Movies: Watching, Questioning and Enjoying had Peter’s name first, so this book has Bill’s name first. The position of our names in no way implies that one of us was the “lead” author or did more than the other. In that spirit, whenever possible we have published our interviews without attributing who asked which questions.

It has been a great privilege for us as film scholars to get to know Blake and watch him work, as we hope this book demonstrates.

Acknowledgments

This book draws heavily on research on Blake Edwards’s films conducted for over three decades. We acknowledge all the many industry and creative contributors who granted us interviews and gave generously of their time and expertise for the book, but we want to give special thanks to the following who gave so much support to us: Tony Adams, Gene Schwam, Ken Wales, Dick Gallup, and James Hirsch.

We are also deeply indebted to our two research assistants who worked with us throughout the process. Elana Shearer organized and scanned many screenplays and interviews and transcribed several. We were new to using Google Docs as collaborators, and whenever we had problems, she quickly solved them for us with good cheer. Jessica Conn did the screen grabs and researched the copyright credits for them. She also was in charge of submitting the manuscript and the screen grabs to Wiley throughout the production process and she continued to guide our use of Google Docs with good cheer. Without Elana and Jessica we’d still be scratching our heads and looking for stuff. Thanks also to Eric Monder.

Finally, this book would not have been possible without more than three decades of support and cooperation from Blake Edwards. He granted us countless interviews, gave us a standing invitation to visit any of his sets, arranged for us to interview many of his business and creative associates, including Julie Andrews, who was always generous, gracious, and complimentary about the importance of our work on Blake’s films. We cannot imagine a greater compliment.

From William Luhr

I would like to thank the New York University Faculty Resource Network, along with Chris Straayer of NYU’s Department of Cinema Studies, who have provided valuable research help and facilities, as has the staff of the Film Study Center of the Museum of Modern Art. Generous assistance has also come from the members of the Columbia University Seminar on Cinema and Interdisciplinary Interpretation, particularly my co-chair, Cynthia Lucia, as well as Krin Gabbard, David Sterritt, Pamela Grace, Martha Nochimson, Robert T. Eberwein, and Christopher Sharrett. Our fruitful and intellectually stimulating seminar has received constant support from Alice Newton, Pamela Guardia, Gessenia Alvarez-Lazauskas, and Summer Hart of the University Seminars Office. At Saint Peter’s University, gratitude goes to the President Eugene Cornacchia, Academic Vice President Frederick Bonato, Academic Dean WeiDong Zhu, English Department Chair Scott Stoddart, Robert Adelson and the Office of Information Technology, the members of the Committee for the Professional Development of the Faculty, John M. Walsh, Rachel Wifall, Jonathan Brantley, Daisy DeCoster, Barbara Kuzminski, Deborah Kearney, David Surrey, Jon Boshart, Leonor I. Lega, and Joseph McLaughlin for generous support, technical assistance, and research help. Keith Ditkowsky and Joseph Mannion have been of valuable help. As always, I am deeply indebted to my parents, Eilleen and Walter; my aunts, Helen and Grace; my brothers, Walter and Richie; as well as Bob, Carole, Jim, Judy, and David.

From Peter Lehman

I would like to thank the Arizona State University deans who supported and encouraged my research and administrative work: College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Deans David Young and Quentin Wheeler and associate and area deans Len Gordon, Deborah Losse, and Neal Lester. Special thanks to President Michael Crow for his support for granting Blake Edwards an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree and for participating in a special hooding ceremony with the ASU Symphony Orchestra celebrating Blake’s films and the music from them. Special thanks also to Timothy Russell for working with me in planning the concert and for his superlative conducting. I still hear the opening and closing performances of Henry Mancini’s theme from Peter Gunn pulsating in my memory of that very special evening. Finally, Joseph Buenker, Associate Librarian, Humanities, went above and beyond the call of duty researching reviews of Edwards’s films in Variety.

As always, I owe my wife Melanie Magisos more than I can ever acknowledge. I’m very lucky to be part of a family of movie lovers, including my brother Steve, my daughter Eleanor and her husband Jason, and my grandchildren Jonah and Lila. I grew up in a home with parents and a grandpa who were regular moviegoers. When my parents who were refugees from Nazi Germany first arrived in New York someone took them to Radio City Music Hall, where they saw their first Mickey Mouse cartoon, after which my mother with great affection nicknamed my father Mickey. And my father never tired of fondly recalling Charlie Chaplin eating his shoe in The Gold Rush, which he saw as a young man in Germany. Movies are powerful.

CHAPTER 1 Introduction: “Call Me Blake.”

Today, Blake Edwards at best is primarily known to the public for ten films he directed at three points in his career beginning with Breakfast at Tiffany’s and The Days of Wine and Roses in the early 1960s; followed by five mid-1960s to mid-1970s Pink Panther films; and culminating with “10,” S.O.B., and Victor/Victoria between 1979 and 1982. But this is only the tip of the proverbial iceberg. Edwards is rightly often considered the most important filmmaker of his generation. Yet even this overlooks the importance of his successful work in radio, television, and theater. It also excludes his extensive work in addition to directing as a writer, producer, and actor as well as his work as a studio artist. In this book we expand and refocus our understanding of this ceaselessly creative multimedia, multi-hyphenate artist, including major screenplays of films that were unproduced, a stage play script that has also not yet been produced, and a survey of his public one-man shows and retrospectives of his work as a studio artist featuring paintings and sculpture.

Although it is not widely known, Blake Edwards began his postwar filmmaking career in 1948 with a B Western, Panhandle, which he cowrote and coproduced and in which he acted. He followed that with another B Western, which he once again cowrote and coproduced. These were very low-budget films for minor studios, Monogram and Allied Artists. Edwards did not rise to sustained public prominence as a film director until over a decade later, as mentioned above, when he made Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), Days of Wine and Roses (1962), and The Pink Panther (1963), all of which were released by prestigious, high-visibility studios (Paramount, Warner Brothers, and United Artists respectively). Yet, between 1948 and the early 1960s, Blake Edwards burst upon the scene as a writer-producer-director-actor in radio, television, and film. He was everywhere doing virtually everything.

We will tell that story in Chapter 2, but we begin here for several reasons. We want to briefly situate Edwards within the historical context of profound changes within the film and television industries between 1948, when he began his career, and 1993, when he directed his last theatrical film; we want to survey the current state of scholarship on Edwards; and we want to outline our goals for this book, where we will minimize repetition from our earlier two books and the work of others since then.

Blake Edwards grew up in Hollywood and often referred to himself as a third-generation filmmaker since his step-grandfather, J. Gordon Edwards, was a silent film director most known for his popular films with Theda Bara. His stepfather, Jack McEdward, was an assistant director as well as a theater director. Distinguished film historian Kevin Brownlow told us a remarkable anecdote about this aspect of Edwards’s family history during a Pordenone Silent Film Festival. Film archivists and historians had long presumed that all of J. Gordon Edwards’s Theda Bara films had been destroyed in a fire. Tragically none had survived even in any international film archives. Remarkably, Brownlow was involved in the discovery and restoration of one of the lost films. Knowing of Edwards’s pride in his family’s place in film history, Brownlow invited Blake Edwards and Julie Andrews to a private screening. Edwards had never seen one of his step-grandfather’s films, and he was deeply appreciative of the screening Brownlow had set up. Brownlow also sent us documents about that private screening. Clearly, the history of film, including the silent era, meant a great deal to Blake Edwards and became a significant influence on him as a filmmaker.

Although Edwards is nearly always thought of as a comedy filmmaker, we will focus attention on the many serious films he made, many of which are forgotten, overlooked, or marginalized. Careful analysis of these films foregrounds the complex and creative way he approached genre conventions in all his films, sometimes mixing genres, sometimes interrogating them, sometimes overwhelming convention with invention, and sometimes satirizing them. We will draw upon decades of research, including visiting the sets of four of his films and two of his plays, watching him work and talking with and interviewing him and many of his creative and business collaborators. We have also conducted formal interviews with dozens of actors, editors, set designers, producers and publicists, and so on.

Blake Edwards has been recognized as an auteur since the 1960s, a status that was highlighted in 1968 with the publication of Andrew Sarris’s groundbreaking book, The American Cinema: Directors and Directions1929–1968. Sarris had placed Edwards in the category “The Far Side of Paradise,” meaning directors immediately below the giants in the Pantheon, even though much of Edwards’s best work would come in the following decades.1 That recognition began in France when Jean-Luc Godard praised Mister Cory (1957) as a serious artistic accomplishment in Cahiers du Cinéma.2 Sarris perceptively summarized aspects of Edwards’s worldview and film style. It was important at the time to make the case for directors as serious artists who could develop their unique visions within the Hollywood studio system, despite its emphasis on box office, stars, and genre entertainment. It was not uncommon in academia at that time for many to consider such directors as Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini as serious artists in contrast to the presumed mere Hollywood entertainers with their eye on the box office.

It is within this context that we published two books on Edwards’s films: the first, simply titled Blake Edwards (1982), and the second, Returning to the Scene: Blake Edwards, Volume 2 (1989).3 In those volumes, we tried to expand Edwards’s auteur standing in two ways. We based our readings of his films on detailed close formal analyses which stressed how such aspects of film style as composition, editing, screen space, and visual motifs all shape and form the story they tell. Secondly, we helped introduce and apply important work in contemporary film theory such as feminist and psychoanalytic theory to expand upon previous auteur criticism of Edwards’s films.

Since the publication of our first two books on Edwards, another major critical study has appeared in 2009: Sam Wasson’s excellent A Splurch in the Kisser: The Movies of Blake Edwards. He chronologically analyzes the films Edwards has directed. As the title suggests, he emphasizes how Edwards used visual style to build such central features of the films as gag structures. This strategy foregrounds how Edwards worked creatively as a filmmaker, minimizing abstract discussions of character, theme, plot, and worldview which could just as well be summarizing novels instead of films. Rather than attempt to footnote every possible reference to his book, we will simply acknowledge its general importance to our work. We published our second book on Edwards on January 1, 1989, and Wasson’s book came 20 years later, and the year before Edwards died. As such Wasson covers all the late-period films released after we finished writing our second book in 1989. At this point in time, we recommend that readers seeking an introduction to the films of Blake Edwards begin with A Splurch in the Kisser. If some of our points seem similar at times, it does not mean there is a direct influence. We have been working on this book for several decades, and much of our research and the directions of our argument took place prior to reading Wasson’s book. For example, we have analyzed Edwards’s gag structure in relation to what Edwards called “topping the topper topper,” a style he credited to Leo McCarey and his work with Laurel and Hardy. There are connections between “topping the topper topper” and the “splurch.” Another shared assumption with Wasson relates to genre: As we reviewed Edwards’s entire career for this book, we were struck by the fact that all of his genre films, radio shows, and television series were unusual departures from the genre norms of the time, so much so that many of them could more accurately be described as genre mixes. Wasson, although focused on the films Edwards directed, makes the same point. Wasson generously credits us with influencing him, and we want to credit him with influencing us. It is due to Wasson’s work that we decided we did not need to focus in detail on all the films that Edwards had made since our previous work, nor did we need to update our previous analyses. That has had a profound impact on the structure of this book, freeing us up to focus on different things.

In addition to Wasson’s book, we are indebted to Richard Brody’s brief, but profound, reevaluation of Edwards’s career in his article “What to Stream: Blake Edwards’s Masterwork Documentary of His Wife, Julie Andrews” in The New Yorker Magazine, March 26, 2020.4 We were not even aware of the 1972 documentary Julie prior to reading this article, and now we have an entire chapter on it in this book. But Brody goes on to reassess Edwards’s entire career, granting that “Edwards (who died in 2010) was a comedic genius, the most skilled and inspired director of physical comedy working in Hollywood in his time,” but then, noting his dissatisfaction with various scenes within those films, he claims, “Yet Edwards has also made some of the best movies of modern times, including ‘Experiment in Terror,’ ‘Days of Wine and Roses,’ ‘Wild Rovers,’ and even ‘Sunset,’ which has been much, and wrongly, maligned, including by Edwards himself.” The argument about these dramas, or “serious” films as they are, regrettably, often labeled since comedies can be just as serious as dramas, along with the documentary Julie, inspired us to devote an entire section of this book to chapter-length analyses of each of the nine non-comic films, including the four Brody singles out. We held these four films in very high regard long before reading Brody’s article, and we had written about three of them, but his spirit of reevaluating the Edwards oeuvre in this fashion inspired us to be the first book to focus an entire section on Edwards’s non-comic films, which we will call “dramas” for short. Those are the only films directed by Edwards that we analyze in such a manner, devoting an entire chapter to each film. Our goal is not just to help change the limited notion of Blake Edwards as “a comic director” but to further explore the relationship between his comedies and these dramas. We were surprised by some of the discoveries we made.

In this book we emphasize three different areas of Edwards’s work: In Chapter 2 we will look at his immensely productive early period in which he burst upon the scene in radio (Richard Diamond, Private Detective), television (Peter Gunn), and film (Operation Petticoat), to hint at what lies beneath the tip of the iceberg. We were fortunate to interview some key figures from that period, including writer-director Richard Quine; composer Henry Mancini; choreographer Miriam Nelson; actor Craig Stevens; and writer-producer-director Owen Crump, since Edwards worked in so many different capacities, beginning primarily as a writer for radio and cowriting a series of screenplays with Richard Quine. He moved up to directing when Quine moved from B films to A films and from Columbia to Universal. Edwards worked extensively with two major figures in this early period: Dick Powell in radio and television, and Richard Quine in film. Interestingly, Edwards only ever mentioned Powell to interviewers including us within one specific context – his abrupt transition from singing and dancing in musicals to being a tough Film Noir detective in Murder, My Sweet (1944). Yet Powell was also a model of a multimedia, multi-hyphenate creator working as an actor and producer in radio, television, and film and may have influenced Edwards to develop his career in that direction. And although both Powell and Quine worked repeatedly with Edwards when they were established figures and he was an up and coming figure, he never called either of them a mentor. Throughout most of his career, he saved that praise for Leo McCarey with whom he never worked but whom he knew well and with whom he had many discussions about filmmaking. McCarey was yet another writer-director-producer. Yet once again, Edwards repeats the same point every time: McCarey’s style of developing visual gags in such a manner that, just when the spectator laughs and thinks it is over (the topper), he extends it in a new direction for another laugh (topping the topper) and the spectator laughs again at what they think is the surprising end to the gag only to have it extended yet again (topping the topper topper). And he always recounted the same example from a McCarey film. Not surprisingly, Edwards called this “topping the topper topper” and it would be the central model for much of the comedy which made him famous and won him critical acclaim. Powell, Quine, and McCarey, three writer-producer-directors, seem to be the most prominent formative figures in Edwards’s early work. By the end of his career, however, as Sam Wasson reminds us, during a distinguished awards ceremony which we attended with Billy Wilder present, Edwards said, “Whether you know it or not, Billy, you have always been my mentor.”5

As we situate Edwards historically as a writer-producer-director, it is important to remember that a long tradition of such hyphenates existed in Hollywood and that several of them also worked in various media and theatrical forms. This began during the silent era before the elaborate compartmentalization of later times emerged. A look at Charles Chaplin’s credits in most of his films gives an indication of this. Chaplin was often the director, producer, star, writer, and at times composed the music and did the choreography. Our argument for the importance of Edwards as a multi-hyphenate, multimedia creator was not that he was an original (far from it) but, rather, that he became the most prominent such creator at a crucial moment in film history defining the post–World War II years up to the contemporary convergence of the entertainment and technology industries when such multi-hyphenate, multimedia creators became a new norm within a totally reorganized entertainment industry. Thus, he not only pointed to the past, but he also became an extraordinary link to the future. During his career both the nature of the film industry and the studio system, and their relationship with television, changed dramatically.

Under the Hollywood studio system when Edwards began, studios had actors and directors under contract and Edwards’s relationship with Columbia Pictures’ founder and president, Harry Cohn, as well as with director Richard Quine and star Frankie Laine was in that sense typical. Quine had a multipicture deal with Columbia to direct a series of films starring Mickey Rooney, and then the popular singer Frankie Laine. These were B films, meaning they had a smaller budget, shorter running times, and were intended as the second half of double features. In addition to their A features, studios such as Columbia frequently also produced such B features. When Quine was elevated to the status of directing larger-budget A features with established film stars, Edwards was assigned to direct the two films in the contracted Frankie Laine series. Edwards’s start at Columbia thus epitomized many aspects of the studio system.

Edwards told us an anecdote about working with Cohn at Columbia. While he and Quine were in production on a film, Cohn called them into his office and complained about the film, saying it needed a scene with a moving speech. When Quine asked if he wanted something like Hamlet’s soliloquy, Cohn replied, “No, something like ‘To be or not to be’.” Edwards lost it and doubled over with laughter. Cohn asked Quine, “What’s the matter with your boy?” Edwards replied, “To be or not to be is Hamlet’s soliloquy.” Cohn then said, “You’re fired.” The studio heads had such power under that system.

When Edwards went to Universal to direct Tony Curtis in the first film that he had written by himself and, outside of the Frankie Laine B series, he was able to do so because of another feature of the studio system: studios often loaned a star or director to another studio. They loaned Richard Quine to Universal in 1954, where he directed Tony Curtis in So This Is Paris, a musical. Edwards was no longer under contract to Columbia, and undoubtedly it was Quine’s presence at Universal along with his having directed Tony Curtis that paved the way for Edwards’s first drama, Mister Cory (1957), which also starred Curtis. When Edwards returned to Columbia Pictures in 1962 to direct Experiment in Terror, the poster boldly announced, “Columbia Pictures Presents a Blake Edwards Production.” His status within the industry had clearly changed. He was no longer a B director or under contract to direct films with stars that were assigned to him.

Edwards had two major transitionary periods in his career. With Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), Experiment in Terror (1962), and Days of Wine and Roses (1962), he transitioned from his early period into his middle period beginning with The Pink Panther in 1963. It was only after The Pink Panther and the box-office success of the five-film series he did with Peter Sellers playing Inspector Clouseau from 1963 to 1978, as well as the many other comedies he made during that time, that he became known as a comic director. In 1962, he was poised as a talented filmmaker in many genres and the diversity of these three transitionary films illustrates this: romantic comedy, a Film Noir–type crime procedural, and a grim social problem drama about alcoholism. Furthermore, two top stars, Audrey Hepburn and Jack Lemmon, had each chosen Edwards to direct their films; he did not originate the projects. Nor did he write the screenplays in any of the three transitional films; it seemed that he wanted to prove that he could tackle any genre and work with top actors. It is then ironic that he became known as a “physical comedy” director from the very beginning of his middle period when, at the last minute, he cast Peter Sellers in a production which he initiated and for which he cowrote the screenplay. Right after proving he could do anything, he zeroed in on slapstick comedy, a form that had languished and which enjoyed little or no critical prestige. This set the stage for the manner in which his non-comic and dramatic films were largely overlooked and underrated. It is startling how quickly the man who directed Experiment in Terror and Days of Wine and Roses, two black-and-white, serious dramas, would be forgotten in the wave of widescreen color slapstick comedies which quickly followed: The Pink Panther (1963), A Shot in the Dark (1964), The Great Race (1965), What Did You Do in the War, Daddy? (1966), The Party (1968), and Darling Lili (1970). And his prominence in such genres as tough guy private eyes in radio and television did not stick to him, not even when, as in 1969, he made Gunn, a feature film adaptation of his late 1950s television hit, Peter Gunn.

Edwards’s second transitionary period from his middle period into his late period was again formed by three films: “10” (1979), S.O.B (1981), and Victor/Victoria (1982). With these films Edwards transitioned from making films with elaborate sexual subtexts, including all five of the Pink Panther films which were widely viewed as just family films. Indeed, leading up to “10,” Edwards had made three Pink Panther films in a row. “10” is a sexually explicit comedy about a man with a midlife crisis; S.O.B. is a sexually explicit comedy about a film producer who transforms a G-rated family picture into an adult film with nudity; and Victor/Victoria is a comedy about a woman pretending to be a man pretending to be a woman. Following the transitionary films, many of Edwards’s late-period films would be sex comedies: The Man Who Loved Women (1983); Micki & Maude (1984); That’s Life! (1986); Blind Date (1987); Skin Deep (1989); and Switch (1991), nearly all of which deal with men having midlife crises (Blind Date is the exception).

Edwards had another type of transition during this middle period that was related to the end of the old studio system and the production and distribution systems in the new Hollywood. Edwards’s trials and tribulations dealing with the collapse of the old studio system and the rise of the new Hollywood conglomerates coincided very closely with his middle period. Edwards, however, felt alienated from the new Hollywood and the conglomerate model. He had bad experiences at Paramount, which had become a Gulf and Western Company headed by Robert Evans, and with James Aubrey at MGM. The manner in which the new breed of CEOs interfered with production and postproduction frequently led to clashes. Edwards told us that at least the old Hollywood moguls knew and cared about movies, whereas the new ones cared only about business. He described the situation as follows: He said he would never presume to tell Gulf and Western where to drill for oil and that they in turn should not tell him how to make movies. He compared the way the new moguls reedited finished films to taking a chair with four legs and cutting one of the legs off. Edwards’s clashes with the new conglomerates began after Gulf and Western acquired Paramount Pictures in 1966, and he made Darling Lili, which was released in 1970. Paramount insisted on changes in the script, making it a more traditional musical which would capitalize on Julie Andrews’s image. The only songs Edwards originally wanted in the film were ones performed by Lili Smith played by Julie Andrews. In other words, the songs were all about performance within the film’s narrative context. In most musicals the characters break into song while interacting with one another. Edwards compromised to make the film but was unhappy with it. In 1992, however, he was honored at the Cannes Film Festival with the Legion of Honor, and his restored director’s cut received its premiere screening. Whereas most directors add scenes to their new versions of their films, Edwards did the opposite, cutting about 30 minutes, including a musical number of children singing in the countryside. Edwards told us that he could not restore the film to his original vision since scenes he wanted had never been shot. This version, however, approximated his vision for the film and is now available on DVD.

Investor Kirk Kerkorian, with holdings in an airline and Las Vegas casinos, bought a controlling interest in MGM in 1969 and appointed James Aubrey as president and CEO. The Hollywood Reporter called Kerkorian “the most hated man in Hollywood,” claiming, “In 1969, the MGM owner needed someone to run his company. He found James T. Aubrey, a former CBS executive who was widely known as the Smiling Cobra. He knew nothing about film, having spent much of his career in television, most notably at CBS.”6 Edwards’s account of his experience with Aubrey when he made Wild Rovers at MGM definitely fits the description. Edwards’s cut told the story within a complex plot structure including sophisticated shifts in time and use of voice-over narration. Aubrey drastically recut it by shortening the film by 30 minutes, making it a straightforward narrative with entire scenes and characters missing. Luckily, once again many years later, a director’s cut appeared on DVD, and this time, the missing footage was restored.

Edwards was devastated by the experience and wanted his next film to be an adaptation of a Kingsley Amis novel, The Green Man, but Aubrey wanted Edwards to direct another MGM property, The Carey Treatment. Edwards agreed to do so only if Aubrey would commit to letting Edwards make The Green Man next. Once again everything went wrong and, due to studio interference, Edwards quit immediately after the completion of principal photography and sued unsuccessfully to have his name removed from the film. In despair, he decided to leave Hollywood and go to England, where Julie Andrews had a television and film deal with Sir Lew Grade’s ITC. This led to the other transition in his creative career, which was short-lived but important. He made an extremely interesting documentary, Julie (1972), about his life with Julie Andrews while she was preparing for a television special, and a feature film, The Tamarind Seed (1974), a serious international spy drama starring Omar Sharif and Julie Andrews. That film is about such complex life transitions with a Russian spy defecting from Russia to England and eventually Canada. But the next project, The Return of the Pink Panther (1975), marked the return of his collaboration with Peter Sellers. The film was a big success and led to Edwards’s successful return to Hollywood, where he quickly followed with The Pink Panther Strikes Again (1976) and Revenge of the Pink Panther (1978). These successes were then followed by the transition to his late period with “10,”S.O.B., andVictor/Victoria, discussed above. When Edwards returned he managed to fit in with the new Hollywood.

All of Edwards’s Pink Panther films with Sellers as Clouseau as well as the later ones with Ted Wass and Roberto Benigni in a similar role were made with United Artists, but this gives a false sense of continuity. Much like Columbia, MGM, and Paramount, United Artists underwent major changes over the years, including in 1967, when TransAmerica purchased the company, and then in 1981, when MGM purchased it from TransAmerica. In short, the United Artists that Edwards worked with in 1963 and 1964 was not the same company to which he returned in the mid-to-late 1970s. And when he returned for the remaining films in the series in 1982 and 1983 and for the last time in 1993, it was once again part of a different conglomerate. Of special interest in this UA history is the fact that, after TransAmerica took over, several leading executives left and formed a new company, Orion Films. Edwards had been so pleased working with them that he made “10,” his first non–Pink Panther film after returning from England, with Orion and he had a wonderful experience, including good box office and good reviews. He made his next film, S.O.B., with Lorimar. Ironically, given all these changes in the new Hollywood, Paramount acquired the distribution rights to Lorimar films after Edwards made it. So, S.O.B., which included a vicious satire of a studio head, David Blackman, based on Robert Evans and played by Robert Vaughan, was released by Paramount while Evans was the CEO! But this caused no problems since Paramount only had distribution rights and no cuts were made.

Between 1983 and 1988 Edwards made six films for Columbia: The Man Who Loved Women (1983), Micki & Maude (1984), A Fine Mess (1986), That’s Life! (1986), Blind Date (1987), and Sunset (1988). Once again, the studio was far different from that where he made Experiment in Terror in 1962. In fact, it was a prime example of what happened in the wake of the demise of the old studio system. The Coca-Cola Company purchased Columbia Pictures in 1982 and was a founding partner in starting a new studio, Tri-Star (for which Edwards made Blind Date and Sunset), forming yet another conglomerate, Columbia Pictures Entertainment, in 1987. Richard Gallop, who had a background in financial law, joined Columbia as a senior vice-president and general counsel in 1981 and led the team negotiating the merger with Coca-Cola. He then became the president and CFO of Columbia Pictures from 1983 to 1986.

Gallop came to Tucson, Arizona, in 1984 for a test audience screening of Blake Edwards’s Micki & Maude. While in Tucson he gave a guest lecture at the University of Arizona film program. Gallop took an interest in us and our first book on Edwards, assisting our research and talking with us about working with Blake. Although Gallop told us that Edwards called him regularly from the set of his current film as he had the night before to talk about ordinary production concerns and they had a follow-up call scheduled, they did not have an antagonistic or difficult relationship. Edwards had a good experience with Columbia and, later, Tri-Star. Edwards told us that he used to think of his battles with Hollywood as sitting by a river waiting for the bodies of his enemy to come floating by until he realized that there were such people downstream waiting for his body to come floating past. Edwards had developed the reputation of being an extremely difficult director for studios to work with after his high-visibility battles and even lawsuits with Evans and Aubrey, but, after returning to Hollywood in 1976, Edwards had no such further battles.

A problem, for example, arose with A Fine Mess, which was originally titled The Music Box. Edwards planned the film as a remake of a Laurel and Hardy short, The Music Box. The central scene showed Laurel and Hardy moving a grand piano up a steep flight of stairs, only to discover that they had the wrong address. After viewing the footage, the studio asked Edwards to cut his version of that scene from his film, which he did, retitling it after the duo’s iconic phrase where Hardy repeatedly berates Laurel by declaring he has gotten them into “a fine mess.” But Edwards did not harbor anger toward studio executives, telling us that he was struggling with serious depression and chronic fatigue syndrome when he made the film. He would even tell us later that he had no memory of even making A Fine Mess and Henry Mancini told us, “That one got away from us” (more on that below).

Edwards followed that bad experience by making the low-budget, non-union independent film, That’s Life!, which Columbia acquired for distribution. Although the film ultimately failed at the box office, the studio was so enthusiastic about the film, which got the highest scores from preview audiences that they had ever seen, they decided to change the planned slow rollout in major cities to a big national opening. Despite the failure, producer Tony Adams told us that neither he nor Blake held bad feelings, adding that the more experience he (Tony) had, the more he concluded that he never knew how any film would do before opening. Skin Deep (1989) and Switch (1991) were Edwards’s last two sex comedies; the former was released by Twentieth Century Fox where he had made High Time in 1960, and the latter by Warner Brothers, where he had made Days of Wine and Roses. Blake Edwards’s production Company, BECO, was involved in both and, once again, there were no bitter battles with the studios.

This brief account of Edwards’s changing relationships with studios and of the changes within the studio system is central to understanding his career trajectory. He was a writer-director at heart seeking maximum control from the very beginning of his career, and he had the usual tensions with the studios at times, but he had no reputation as a difficult director until the 1970s. All of that changed dramatically with three films in a row with widely publicized bitter battles: Darling Lili, Wild Rovers, and The Carey Treatment. Paramount accused Edwards of going well over budget with Darling Lili, a film that failed badly at the box office. Edwards felt that that experience unjustly gave him the bad reputation that he carried for many years. The following battles with MGM over cuts in Wild Rovers and production interference during The Carey Treatment threatened to end his career in Hollywood but, after his brief period in England, he returned to Hollywood and worked for two decades that were free of such extreme turbulence. His late-period films had modest budgets, and he completed them without delays and without going over budget. He had successfully transitioned from the old to the new Hollywood.

In order to fully understand Edwards’s career achievements, we also need to briefly look at the television industry during this time period. Edwards was an important figure in television in the late 1950s, achieving his greatest success with Peter Gunn (1958–1961), a half-hour black-and-white private eye series. At that time television was seen as a starting point for those with ambitions to become film directors. The same was true for actors. Successful film directors seldom moved to television, and movie stars seldom acted on television. Most of the exceptions were actors and directors whose careers had peaked and who could no longer find work in film. There was at this time a strict hierarchy between film and television with film at the top. As always, there were a few exceptions such as Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1955–1962).

Once again, Edwards’s career does not conform to the norm. After working as an actor in mostly small roles from 1942, he began his behind-the-camera work in film as a writer-producer of two B Westerns, Stampede and Panhandle, in 1948–1949. In 1949 he created and wrote most of the episodes for Richard Diamond, Private Detective. By 1952 he was already writing screenplays with director Richard Quine: Sound Off and Rainbow Round My Shoulder. Edwards would write four more screenplays with Quine between 1952 and 1954. During those years he also wrote nine episodes for Four Star Playhouse on television and created The Mickey Rooney Show for television with Quine. He directed five of the nine episodes on Four Star Playhouse, and, in 1954, he also wrote and directed an unsold television pilot: Mickey Spillane’s “Mike Hammer!”.