32,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: New Approaches to Film Genre

- Sprache: Englisch

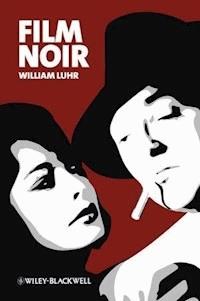

Film Noir offers new perspectives on this highly popular and influential film genre, providing a useful overview of its historical evolution and the many critical debates over its stylistic elements.

- Brings together a range of perspectives on a topic that has been much discussed but remains notoriously ill-defined

- Traces the historical development of the genre, usefully exploring the relations between the films of the 1940s and 1950s that established the "noir" universe and the more recent films in which it has been frequently revived

- Employs a clear and intelligent writing style that makes this the perfect introduction to the genre

- Offers a thorough and engaging analysis of this popular area of film studies for students and scholars

- Presents an in-depth analysis of six key films, each exemplifying important trends of film noir: Murder, My Sweet; Out of the Past; Kiss Me Deadly; The Long Goodbye; Chinatown; and Seven

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 457

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Praise for Film Noir

New Approaches to Film Genre

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

List of Plates

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1: Introduction

The Longevity of Film Noir

The Structure of This Book

Chapter 2: Historical Overview

Double Indemnity

Beginnings

Popularity and Parody

Gender Destabilization: Broken Men and Empowered Women

Social Context

The Late 1940s: New Influences and Changes in Film Noir

The 1960s: Transition in Hollywood and Revival of Film Noir

The Revival of Classical Hollywood and the Rise of Neo-Noir

Changes in Film Censorship, Self-Referentiality, and Genre Blending

Chapter 3: Critical Overview

Emergence of a New Sensibility in American Film

Early English-Language Discourse on Film Noir

The Proliferation of Film Noir Studies

Perspectives on the Generic Status of Film Noir

The Reception Context of Film Noir

Chapter 4: Murder, My Sweet

A New Direction for Detective Movies

Four Major Trends in Film Noir

Farewell, My Lovely and Neo-Noir

Chapter 5: Out of the Past

The Filmmakers

Narrative Complexity, Character Ambiguity, and Critical Acceptance of Film Noir

Retrospective Narration and the Power of the Past

Subtextual and Symbolic Meanings – Censorship, Race, Nation

Neo-Noir and L.A. Confidential

Chapter 6: Kiss Me Deadly

Mike Hammer and His Corrupt World

“Pulp” Atmosphere and Censorship Problems

Formal Strategies

Atomic Age Consumerism and Paranoia

Nuclear Fission, Science Fiction, Apocalypse, and Resurrection

Critical Reputation

Chapter 7: The Long Goodbye

The Film

Hostile Initial Reception

Marlowe

Leigh Brackett, Chandler, Generic Change, and Marlowe

Formal Strategies

The Long Goodbye and Non-Detective Films Noirs

Chapter 8: Chinatown

Chinatown as Neo-Noir

Deceptive Appearances, Prejudicial Blindness, and Los Angeles's Chinatown

Los Angeles History and Identity

Immigrant Directors

Genre Transformation

Chapter 9: Seven

Continuity with Film Noir

Change and Evolution in Film Noir

Seven and Neo-Noir

Afterword

References

Further Reading

Index

Praise for Film Noir

“William Luhr is the intrepid sleuth of cinema studies, tracking down film noir under all the aliases – classic noir, pre-noir, neo-noir – that its infinite variety has produced. Writing with energy, clarity, and verve, Luhr explodes narrow conceptions of noir as conclusively as the Great Whatsit blew up postwar innocence in Kiss Me Deadly. Carry a copy of this timely, spirited book in your trenchcoat. It is a boon for film scholars, general readers, and movie buffs alike.”

David Sterritt, Chairman, National Society of Film Critics

“Informed by a rich body of previous scholarship, conceptually sophisticated, yet written with grace and clarity, Film Noir by William Luhr provides an ideal introduction for students and fans to the dark corner of American culture represented by these gloriously perverse crime films.”

Jerry W. Carlson, PhD, The City College & Graduate Center, CUNY

“William Luhr, who knows all the many questions raised by film noir, supplies lucid, elegant, provocative answers. His knowledge is deep, his comments far-ranging. This is an essential addition to the vast literature on the genre.”

Charles Affron, New York University

“Writing with broad expertise and deep sensibility, Professor Luhr heightens our nostalgic delight in noir films while also pointing to the lost spectatorial experience of film noir's once present tenseness.”

Chris Straayer, New York University Department of Cinema Studies

New Approaches to Film Genre

Series Editor: Barry Keith Grant

New Approaches to Film Genre provides students and teachers with original, insightful, and entertaining overviews of major film genres. Each book in the series gives an historical appreciation of its topic, from its origins to the present day, and identifies and discusses the important films, directors, trends, and cycles. Authors articulate their own critical perspective, placing the genre's development in relevant social, historical, and cultural contexts. For students, scholars, and film buffs alike, these represent the most concise and illuminating texts on the study of film genre.

From Shane to Kill Bill: Rethinking the Western, Patrick McGee

The Horror Film, Rick Worland

Hollywood and History, Robert Burgoyne

The Religious Film, Pamela Grace

The Hollywood War Film, Robert Eberwein

The Fantasy Film, Katherine A. Fowkes

The Multi-Protagonist Film, María del Mar Azcona

The Hollywood Romantic Comedy, Leger Grindon

Film Noir, William Luhr

Forthcoming:

The Hollywood Film Musical, Barry Keith Grant

This edition first published 2012

© 2012 William Luhr

Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007.

Blackwell's publishing program has been merged with Wiley's global Scientific,

Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Registered Office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex,

PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of William Luhr to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Luhr, William.

Film noir / William Luhr.

p. cm. – (New approaches to film genre)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4051-4594-7 (hardback : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4051-4595-4

(pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Film noir–United States–History and criticism. I. Title.

PN1995.9.F54L84 2012

791.43′6556–dc23

2011041410

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book is published in the following electronic formats: ePDFs 9781444355925; Wiley Online Library 9781444355956; ePub 9781444355932; Kindle 9781444355949

For Peter Lehman,Who knows the darkness,But has kept the music playing

List of Plates

1.Double Indemnity – credits: Silhouette of a man on crutches approaching the viewer

2.Double Indemnity: Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) speaking into a dictaphone

3.Double Indemnity: Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck) enticing Walter into murder

4.Sunset Boulevard: The film is narrated by the corpse of Joe Gillis (William Holden) as it floats face down in a swimming pool

5.D.O.A: Frank Bigelow (Edmund O'Brien) opens the movie by reporting his own murder

6.Sin City: White-on-black silhouette of a young couple kissing in the rain

7.The Big Sleep: Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, a popular noir couple

8.My Favorite Brunette: Bob Hope in the opening scene on death row

9.The Killers: “The Swede” (Burt Lancaster) inexplicably awaiting his own murder

10.The Blue Dahlia: Homecoming World War II GIs in a bar – “Well, here's to what was”

11.Naked City: Out-of-studio, documentary-like cinematography in the climax atop New York City's Williamsburg Bridge

12.T-Men – opening: Documentary images of the US Treasury Department Building

13.T-Men: US Treasury Department official Elmer Lincoln Irey directly addressing the viewer in the movie's prologue

14.T-Men: A trapped man is murdered in a steam room as his sadistic killer watches through glass

15.Blade Runner: Harrison Ford's cynical, detective-like character in a futuristic, dystopian city

16.Murder, My Sweet – opening police interrogation: Marlowe (Dick Powell) with eyes bandaged

17.Murder, My Sweet: Marlowe's “crazy, coked-up dream”

18.Murder, My Sweet: Mrs Grayle (Claire Trevor) acting seductively toward Marlowe

19.Farewell, My Lovely: An aging Robert Mitchum as Marlowe

20.Out of the Past: Jeff (Robert Mitchum) and Ann (Virginia Huston) fishing idyllically

21.Out of the Past: Kathie (Jane Greer) meeting Jeff in Acapulco

22.Out of the Past: Jeff's shocked reaction at coming upon Whit's body

23.Out of the Past: Jeff and Kathie on the beach – “Baby, I don't care”

24.L.A. Confidential: An idyllic 1950s family watching Badge of Honor on television

25.L.A. Confidential: Riot in the police station

26.Kiss Me Deadly: Mike (Ralph Meeker) crushes the coroner's hand

27.Kiss Me Deadly: Christina (Cloris Leachman) tortured as Mike lies unconscious on the bed

28.Kiss Me Deadly: Coroner, Gabrielle (Gaby Rodgers), and Mike, photographed from the point of view of the morgue slab on which Christina's body lies

29.Kiss Me Deadly: Gabrielle opens the box containing “the Great Whatsit” – blinding, deadly light

30.Kiss Me Deadly: Explosion at the beach house

31.Kiss Me Deadly: Oppressive visual environment – the stairway near Gabrielle's rooms

32.The Long Goodbye: Marlowe (Elliott Gould) in the supermarket looking for cat food

33.The Long Goodbye: Police interrogation scene with five focal points

34.The Long Goodbye: Roger Wade (Sterling Hayden) in a potentially violent scene with his abused wife (Nina van Pallandt)

35.The Long Goodbye: Marlowe and Eileen Wade inside her home. Through the window, we see Roger Wade on the beach outside as he slowly emerges from the bottom/center of the frame to commit suicide

36.Chinatown: Gittes (Jack Nicholson) and Evelyn (Faye Dunaway)

37.Chinatown: Evelyn – “My sister and my daughter”

38.Chinatown: Noah Cross (John Huston) seizes Evelyn's daughter

39.Chinatown: “Forget it, Jake. It's Chinatown”

40.Chinatown: Noah Cross and Gittes

41.Seven: Somerset (Morgan Freeman) and Mills (Brad Pitt) meeting for first time

42.Seven: Mills at one of John Doe's murder scenes

43.Seven: John Doe (Kevin Spacey)

44.Seven: Tracy (Gwyneth Paltrow) confessing her fears

Acknowledgments

First, thanks go to my colleagues at Wiley-Blackwell. Series Editor Barry Keith Grant has been a patient and helpful editor as well as a good friend. Jayne Fargnoli has been enthusiastically supportive on this and other projects and has my gratitude and admiration. I have received extensive editorial assistance with the manuscript from Mrs Barbara Kuzminski, and indispensable help with photographic and technical matters from David Luhr. Paula Gabbard has guided me in issues of arts permissions and design. Francis M. Nevins has an encyclopedic knowledge of film noir and has been frequently generous.

Thanks to the New York University Faculty Resource Network and its Director, Debra Szybinski, along with Chris Straayer and Robert Sklar of the Department of Cinema Studies, who have been valuable in providing research help and facilities, as have Charles Silver and the staff of the Film Study Center of the Museum of Modern Art. Generous assistance has also come from the members of the Columbia University Seminar on Cinema and Interdisciplinary Interpretation, particularly my co-chair, Krin Gabbard, who has gone out of his way to be personally supportive and intellectually generous for years and under difficult circumstances. He is a truly remarkable friend for whom I am deeply grateful. Christopher Sharrett's knowledgeable conversations about film history and friendship are gratifying. Other generous colleagues in the Seminar include David Sterritt and Pamela Grace. Thanks also to Robert L. Belknap and Robert Pollack, Directors of the University Seminars, and the Seminar Office's essential staff, particularly Alice Newton. I express particular appreciation to the University Seminars at Columbia University for their help in publication. The ideas presented in this book have benefited from discussions in the University Seminar on Cinema and Interdisciplinary Interpretation. At Saint Peter's College, gratitude goes to the President, Eugene Cornacchia; Vice President, Marylou Yam; Academic Dean, Velda Goldberg; Mary DiNardo; Bill Knapp and the staff of Information Technologies; Frederick Bonato, David Surrey, and the members of the Committee for the Professional Development of the Faculty; Lisa O'Neill, Director of the Honors Program; Jon Boshart, Chair of the Fine Arts Department; John M. Walsh; Thomas Kenny; and Oscar Magnan, SJ, and Leonor I. Lega for generous support, technical assistance, and research help. My ability to do this work owes a great deal to the great talents and kindness of Keith Ditkowski, Robert Glaser, and Joseph Mannion. As always, I am deeply indebted to my Father as well as to Helen and Grace; Walter and Richie; Bob, Carole, Jim, Randy, Judy, and David.

Chapter 1

Introduction

The ominous silhouette of a man on crutches approaching the camera that appears under the opening credits of Double Indemnity (1944) provides a prototypical image for film noir (Plate 1). Something is wrong – with the man's legs, with the man, with what will follow these credits – and the grim orchestral music accompanying the image reinforces this impression. The silhouette applies not to a single character but to three men in the film: one a murderer, one his victim, and the third an innocent man set up to take the blame for the crime. All three are drawn into this ugly vortex by the same seductive woman who exploits them and orchestrates their doom. The dark silhouette also menaces the viewer's space – it comes at us, it somehow involves us in whatever is to happen, and whatever it is won't be nice. Something is wrong.

Plate 1Double Indemnity – credits: Silhouette of a man on crutches approaching the viewer. © 1944 Paramount Pictures, INC.

This image appeared at the dawn of film noir, before the term was even coined. Double Indemnity establishes one, but only one, paradigm for the genre. It concerns an adulterous couple who murder the woman's husband for insurance money; in doing so, they generate their own doom. Everybody loses. The story is told mostly in flashback by the guilty man at a point just after he killed his lover and was, himself, shot by her (Plate 2). This retrospective storytelling strategy, heavily reliant on voice-over narration, was innovative at this time and shapes the viewer's response to the film's events in three significant ways. First, it presents the story not from an “objective” perspective but rather from its narrator's perspective, drawing us into his anxieties, moral failures, and feelings of entrapment. It makes our main point of identification not someone who conformed to contemporary Hollywood moral codes but rather someone who violated them. This eliminated traditional viewer security in presumptively identifying with the main characters. Even if such characters in traditional movies were doomed – as when, for example, (1935) ended with Sydney Carton going to the guillotine – those movies presented that doom as heroic and uplifting. But the doom of many characters in is neither noble nor uplifting, and viewer empathy with such characters can be destabilizing.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!