Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

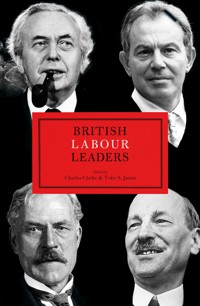

As the party that championed trade union rights, the creation of the NHS and the establishment of a national minimum wage, Labour has played a crucial role in the shaping of British society. And yet the leaders who have stood at its helm – from Keir Hardie to Sir Keir Starmer, via Clement Attlee, Tony Blair and Jeremy Corbyn – have steered the party vessel with enormously varying degrees of success. The requirements, techniques and goals of the Labour leadership since the party's inception at the turn of the twentieth century have been forced to evolve almost beyond recognition – and not all its leaders have managed to keep up. This comprehensive and enlightening book – now fully updated with chapters on all Labour leaders up to Keir Starmer and an assessment of the party's leadership in relation to Brexit – considers the attributes and achievements of each leader in the context of their respective time and diplomatic landscape. Offering a compelling analytical framework by which they may be judged, it also provides detailed personal biographies from some of the country's foremost political critics and exclusive interviews with former leaders themselves. An indispensable contribution to the study of party leadership, British Labour Leaders is the essential guide to understanding British political history and governance.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 686

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BRITISH LABOUR LEADERS

EDITED BY Charles Clarke and Toby S. James

CONTENTS

PREFACE

This book arises from a collaboration between the University of East Anglia and Queen Mary University of London, designed to focus upon issues in political leadership. The project has been supported by the political leadership sub-group of the Political Studies Association.

It began with a seminar at UEA on 17 January 2014, entitled ‘Political Leadership and Statecraft in Challenging Times’. This was then followed by a seminar on Labour leaders on 28 June 2014 at UEA London, and then one on Conservative leaders on 5 December 2014 at Queen Mary University of London.

The purpose of all these was to think about how we can assess party leaders and what it takes to be a successful leader, and then to evaluate who has been more, or less, successful. The seminars were an essential part of the background to this book and we are grateful to Hussein Kassim, Lee Marsden, Josh Gray, Catrina Laskey and Natalie Mitchell for helping to make them a success.

We would particularly like to thank the biographers of the political leaders, who contributed to the seminars and who have written the chapters in this book. Their commitment has made the whole project possible and the standard of their contribution has been outstanding. Equally, the thoughts, reflections and time of Neil Kinnock and Tony Blair were greatly appreciated. Bringing the transcripts of their interviews together would not have been possible without the research assistance of Josh Gray.

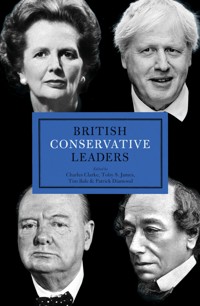

This book, British Labour Leaders, has a companion, British Conservative Leaders, which we also edited, together with Professor Tim Bale and Patrick Diamond from Queen Mary University of London, with whom we very much enjoyed working. A further volume, British Liberal Leaders, to which we have both contributed chapters, has been edited by Duncan Brack and colleagues from the Liberal History Group. We believe that the three books together make an important contribution to the study of political leadership in Britain.

We would like to thank Iain Dale and Olivia Beattie at Biteback, who have been a pleasure to work with as we have brought this book towards publication.

Finally, we would like to thank our families, who have supported us throughout.

Charles Clarke and Toby S. James

Norwich, June 2015

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

Figure 1.1: Conscience, cunning and complete leadership.

Table 1.1: Labour leaders’ statecraft success and failures, 1900–2015.

Figure 2.1: The Labour Party’s vote share and seat share in the House of Commons at general elections, 1900–2015.

Table 2.1: Contextual factors to be considered when assessing leaders.

Table 3.1: Labour performances in each of the twenty-nine general elections, 1906–2015.

Table 3.2: Labour performances in each of the twenty-nine general elections, 1906–2015, ranked by seats gained or lost.

Table 3.3: Labour performances in each of the twenty-nine general elections, 1906–2015, ranked by share of vote gained or lost.

Table 3.4: Overall cumulative Labour leaders’ performances in the twenty-nine general elections, 1906–2015, ranked by seats gained or lost.

Table 3.5: Overall cumulative Labour leaders’ performances in the twenty-nine general elections, 1906–2015, ranked by share of vote gained or lost.

Table 3.6: Leaders’ ‘league table’, ranked by seats.

Table 3.7: Labour performances in votes gained or lost in the twenty-nine general elections, 1906–2015.

Table 3.8: Overall cumulative Labour leaders’ performances in the twenty-nine general elections, 1906–2015, ranked by votes gained or lost.

Table 3.9: Performances of Labour leaders of the opposition.

Table 3.10: Labour leaders in previous rankings of British prime ministers.

Table 7.1: Labour Party performance in general elections, 1922–29.

Table 7.2: Labour Party performance in general elections, 1931–35.

Table 15.1: The 1983, 1987 and 1992 general election results.

Table 15.2: Labour leaders of the opposition, 1937–2015.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES

TIM BALE graduated from Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge, completed a Master’s at Northwestern University and earned his PhD from Sheffield. He specialises in political parties and elections in the UK and Europe. Tim’s media work includes writing for the Financial Times, The Guardian, the Telegraph and The Observer. He has also appeared on various radio and television programmes to talk about politics. In 2011, he received the Political Studies Association’s W. J. M. Mackenzie Book Prize for The Conservative Party from Thatcher to Cameron. He has since published The Conservatives Since 1945: The Drivers of Party Change, the third edition of European Politics: A Comparative Introduction, and Five-Year Mission: The Labour Party Under Ed Miliband.

TONY BLAIR was Prime Minister of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from May 1997 to June 2007. He was also the leader of Britain’s Labour Party from 1994 to 2007 and the Member of Parliament for Sedgefield, England, from 1983 to 2007.

BRIAN BRIVATI has published extensive work on contemporary British politics, with an emphasis on the political history of the British Labour Party, and currently works in international development and capacity building. He is academic director of the PGI Cyber Academy. His biography of Hugh Gaitskell received ten book-of-the-year selections. He has also written a biography of Lord Goodman and edited The Uncollected Michael Foot: Essays, Old and New, 1953–2003, Alan Bullock’s single-volume edition of Ernest Bevin, Guiding Light: The Collected Speeches of John Smith, The Labour Party: A Centenary History, Michael’s Foot’s single-volume edition of Aneurin Bevan, 1897–1960, and New Labour in Power: Precedents and Prospects.

JIM BULLER is a senior lecturer in politics at the University of York. He has a PhD from the University of Sheffield and has previously worked in the department of political science and international studies at the University of Birmingham. He has written widely on the subject of British politics and public policy, including recent articles in the New Political Economy, British Journal of Politics and International Relations, West European Politics, Contemporary European Politics and British Politics. He has recently co-edited a special issue of Parliamentary Affairs on ‘Assessing Political Leadership in Context – British Party Leadership During Austerity’. He is also chair of the PSA Anti-Politics and Depoliticisation Specialist Group.

CHARLES CLARKE was Member of Parliament for Norwich South from 1997 to 2010. He served as Education Minister from 1998 and then in the Home Office from 1999 to 2001, before joining the Cabinet as Minister without Portfolio and Labour Party chair. From 2002 to 2004, he was Secretary of State for Education and Skills, and then Home Secretary until 2006. Charles was previously chief of staff to Leader of the Opposition Neil Kinnock. He now holds visiting professorships at the University of East Anglia, Lancaster University and King’s College London, and works with educational organisations internationally. He edited The ‘Too Difficult’ Box and co-edited British Conservative Leaders.

THOMAS HENNESSEY is a professor of modern British and Irish history at Canterbury Christ Church University. After completing his doctorate, Hennessey was: a junior research fellow at the Institute of Irish Studies, Queen’s; a research officer at the Centre for the Study of Conflict, University of Ulster; a research assistant at the think tank Democratic Dialogue; and a research fellow at the School of Politics, Queen’s. He was also a member of the Ulster Unionist Party’s talks team during the negotiation of the Belfast Agreement (Good Friday Agreement) in 1998. Hennessey joined the history team at Canterbury Christ Church that same year. He is the author of Optimist in a Raincoat: Harold Wilson, 1964–70, among many other publications.

DAVID HOWELL is a professor emeritus of politics at the University of York. He has written extensively on the British labour movement. His publications include MacDonald’s Party: Labour Identities and Crisis 1922–31, and he is an editor of the Dictionary of Labour Biography. His latest book is Mosley and British Politics 1918–32, Oswald’s Odyssey.

TOBY S. JAMES is senior lecturer in British and comparative politics at the University of East Anglia. He has a PhD from the University of York and has previously worked at Swansea University and the Library of Congress, Washington, DC. He is the co-convenor of the PSA’s Political Leadership Group and has published on statecraft theory and political leadership in journals such as the British Journal of Politics and International Relations, Electoral Studies and Government and Opposition, including co-editing a special issue of Parliamentary Affairs on ‘Assessing Political Leadership in Context – British Party Leadership During Austerity’. He is the author of Elite Statecraft and Election Administration and co-edited British Conservative Leaders.

PETER KELLNER has been president of the pioneering online survey research company YouGov since April 2007, having served as chairman from 2001 until 2007. During the past four decades, he has written for a variety of newspapers, including The Times, the Sunday Times, The Independent, The Observer, the Evening Standard and the New Statesman. He has also been a regular contributor to Newsnight (BBC Two), A Week in Politics (Channel 4), Powerhouse (Channel 4), Analysis (Radio 4) and election night results programmes on television and radio. He has written, or contributed to, a variety of books and leaflets about politics, elections and public affairs. He is co-author of Callaghan: The Road to Number Ten.

NEIL KINNOCK was Member of Parliament for Bedwellty (then Islwyn) in south Wales from 1970 until 1995, and leader of the Labour Party from 1983 until 1992. He then served as a European Commissioner from 1995 to 2004, and, in 2004, became a peer.

WILLIAM W. J. KNOX (Bill Knox) is an honorary senior research fellow at the Institute for Scottish Historical Research, University of St Andrews, and the author of a number of books and articles on the labour movement in Scotland. In this field, his major publications are Scottish Labour Leaders, 1918–1939: A Biographical Dictionary and Industrial Nation: Work, Culture and Society in Scotland, 1800–Present. He has also written on a wide variety of other subjects, including women’s history, American multi-nationals in post-1945 Scotland, and crime, protest and policing in nineteenth-century Scotland. He is currently researching the history of interpersonal violence in Scotland 1700–1850, as well as co-authoring a biography of Jimmy Reid.

KENNETH O. MORGAN was a fellow and tutor at The Queen’s College, Oxford, 1966–89, vice-chancellor at the University of Wales, 1989–95, and is now visiting professor at King’s College London. He has lectured in universities in the US, Canada, France, the Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Spain, Latvia, South Africa, India, Malaysia and Singapore. He has been a fellow of the British Academy since 1983 and a Labour peer since 2000. His thirty-four books include: Wales in British Politics; Consensus and Disunity; Wales: Rebirth of a Nation; Labour in Power 1945–51; The Oxford Illustrated History of Britain; Labour People; The People’s Peace; Revolution to Devolution; and biographies of Lloyd George, Keir Hardie, Lord Addison, James Callaghan and Michael Foot.

JOHN RENTOUL is chief political commentator for the Independent on Sunday, visiting professor at King’s College London, and author of Tony Blair: Prime Minister, a new edition of which was published in 2013. He has written about Blair since publishing an early biography in 1995 – the year after Blair became Labour leader. At King’s, he teaches a Master’s course in politics and government called ‘The Blair Government’.

STEVE RICHARDS is established as one of the most influential political commentators in the country. He became The Independent’s chief political commentator in 2005, having been political editor of the New Statesman and a BBC political correspondent. He presents Radio 4’s Week in Westminster and presented ITV’s Sunday Programme for ten years. He is the author of Whatever It Takes.

JOHN SHEPHERD is a visiting professor of modern British history at the University of Huddersfield. He has published extensively on British political and Labour history, and is the author of George Lansbury: At the Heart of Old Labour.

MARK STUART is assistant professor in the faculty of social sciences at the University of Nottingham. He is the author of John Smith: A Life and has published in journals including Political Studies and British Journal of Politics and International Relations.

NICKLAUS THOMAS-SYMONDS was elected as Labour MP for Torfaen at the 2015 general election, having served as the secretary of the Blaenavon branch of the Labour Party, and as secretary of the Torfaen Constituency Labour Party. He lives in Abersychan with his wife Rebecca and his daughters Matilda and Florence. He grew up in Blaenavon and was educated at St Alban’s RC High School, Pontypool, before reading philosophy, politics and economics at St Edmund Hall, Oxford, where he was subsequently lecturer in politics, specialising in twentieth-century British government. Prior to his election to Parliament, he was a practising barrister at Civitas Law, Cardiff. A fellow of the Royal Historical Society, he often writes articles on UK politics, and has been a regular newspaper reviewer on BBC Radio Wales. He is the author of Attlee: A Life in Politics and Nye: The Political Life of Aneurin Bevan.

MARTIN WESTLAKE has published widely on the European institutions and on European and British politics, and is the author of Kinnock: The Biography. He is currently a visiting professor at the College of Europe (Bruges) and a senior visiting fellow at the European Institute of the London School of Economics.

PHIL WOOLAS was Labour MP for Oldham East & Saddleworth for thirteen years. He served as parliamentary private secretary to Lord Gus MacDonald, as Minister of State for Transport, as Lord Commissioner of the Treasury, as Deputy Leader of the House of Commons, as Minister of State for Local Government and Regeneration, as Minister of State for Civil Contingency, as Minister of State for the Environment, and as Minister of State for Immigration and Customs. He also served as a regional minister for the north-west of England. Prior to his time in Parliament, Phil served as a national official for the GMB trade union. His early career was in television, where he worked for ITV, Newsnight and Channel 4 News. He has published numerous articles and essays and is a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. He is currently writing a biography of John Robert Clynes.

CHRIS WRIGLEY was a professor of modern British history at Nottingham University (1991–2012) and is now professor emeritus. He was a University of East Anglia undergraduate 1965–68, president of the Historical Association 1996–99, chair of the Society for the Study of Labour History 1997–2001, and a vice-president of the Royal Historical Society 1997–2001. He was leader of the Labour Group on Leicestershire County Council 1986–89, and a parliamentary candidate in 1983 and 1987. His books include biographies of Henderson, Lloyd George, Churchill and A. J. P. Taylor, as well as studies of Lloyd George and Labour, British trade unions and British industrial relations.

FOREWORD

CHARLES CLARKE

The quality of political leadership matters.

Our political leaders are under greater pressure than ever before as their decisions and actions are scrutinised and challenged – instantly and comprehensively. And failure, as with both Ed Miliband and Nick Clegg in 2015, is punished immediately by departure.

The decisions themselves, whether about overall stance, orientation, strategy or policy, are increasingly complex, with long-term implications. Personal behaviour can easily generate public controversy.

And our global interdependence, notably in relation to the economy, means that British political leaders are increasingly constrained in their freedom to act, even when they wish to do so.

It is our political leaders whose overall stance, strategies, decisions and actions, or lack thereof, determine how our society and economy deal with the problems they face in a world that is changing increasingly rapidly.

Of course, leadership is not only about the leaders of political parties and governments; it is also about a wide range of dispersed leadership, both in national and local politics and throughout the country – in business, public services and our communities.

However, the role of national political leadership is central – and has never been more so.

The purpose of this book is to assess the nature of Labour’s political leadership over the period from the party’s foundation until the present day.

We have done that through the lens of the ‘statecraft’ framework, which Toby S. James and Jim Buller set out in Chapter 2, and through my comparison of general election performances, described in Chapter 3. This is brilliantly illuminated by biographies of all Labour’s leaders from Keir Hardie to Ed Miliband. We have erred on the side of inviting authors who were likely to be defenders of their subject, rather than critics, as leadership is a tough role, and we think the leaders deserve the respect of being assessed by authors who have sympathy for their many dilemmas.

Over the period, the challenges and objectives of Labour political leadership have changed dramatically.

Though the Houses of Parliament and the panoply of politics all seem untouched over the decades, the whole context within which politics has been conducted has been utterly transformed. The franchise has been enormously widened, the values of our society are completely different, there have been revolutionary changes in the media, and the world has been globalised. Consequently, the techniques and skills of political leadership have changed, almost beyond recognition.

At the same time, the goals of Labour leadership have been transformed, too. The challenge for the early leaders was simply to get the largest possible voice in Parliament for working people. But since MacDonald, Labour’s first Prime Minister, it has been about leading, or seeking to lead, government and the whole country, not simply advancing the interests of a particular class or section of the population.

The ways in which these goals were pursued, as well as the techniques used, varied dramatically from leader to leader. At every change, the Labour Party had to choose a new political leader who combined both his/her own individual, personal leadership attributes with the general political direction (s)he was likely to follow.

After their elections, the chosen leaders, like the Labour Party itself, had to face profound choices as to the way in which they responded to particular events, as well as the best objective to target, the best strategic course to follow, and the most effective organisation and techniques to use. They were often challenged in their choices and their conduct, from both within and without the party they led. They all had to deal with alternative approaches, and sometimes alternative people, throughout the course of their leadership.

These tests, all in their different circumstances, are vividly described for each leader in the chapters of this book.

The quality of political leadership is insufficiently considered. What the accounts in this book demonstrate is that the overall leadership quality of each leader does matter, together with their personality and vision. Things could have been done differently – perhaps better, perhaps worse – and the outcomes could have been different (though in what precise way perhaps goes too far into the counter-factual).

Some commentators tend to suggest that the quality of a Labour leader, or potential leader, can be reduced to just physical appearance, particular communication skills or personal history. Others may think it simply to be a matter of ideology, political direction, or even a particular policy seen as symbolic.

But this book seeks to encourage the view that the quality of political leadership is not only important in its own right – more important than people sometimes allow – but that this quality needs to be judged widely and across a number of different attributes.

We seek to offer a means of considering the quality of Labour’s political leaders, to suggest that general election performance is a useful means of comparing them, and to urge that the Labour Party, as well as other parties, gives the highest possible consideration to the overall quality of political leadership when choosing its leaders.

PART I

FRAMEWORKS FOR ASSESSING LEADERS

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION: THE BRITISH LABOUR PARTY IN SEARCH OF THE COMPLETE LEADER

TOBY S. JAMES

Party leaders are commonly the focal point for discussion about politics and policy in Britain, as they are in many democracies. Elections, conference seasons, manifesto launches, TV debates, Prime Minister’s questions – in nearly every aspect of practical politics the media zooms its lens on the leader. Among the public, ‘Miliband’, ‘Farage’, ‘Cameron’, ‘Salmond’, ‘Clegg’, ‘Blair’ and ‘Thatcher’ are easy proxies for discussing the policies of the parties about which they often know less. Behind closed doors, leaders play a vital role in shaping the policy platform of their party, agree votes on parliamentary bills, negotiate post-election coalitions and pacts with their opponents, deal with rogue backbenchers, and represent their country in meetings with foreign leaders and international organisations.

Party leaders, therefore, matter. The fortunes of their party, their members and their country depend on them. A party leader without the communication skills to present their vision will never be taken seriously. A leader who fails to end internal divisions could leave their party out of power for a generation. A leader who makes key strategic errors could see the national interest damaged.

The Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle once claimed that ‘the history of the world is the history of great men’.1 This does overemphasise the transformative capacities that all leaders can have. They face constraints. Not all are capable of delivering change, leading an ill-disciplined party to electoral victory or reversing the course of history by themselves. But even in the most challenging of circumstances, they can make a difference, if only to steady a ship. To ignore how a skilled leader can re-shape their times is to misunderstand history, politics and society in Britain.

WHO IS BEST?

It follows that assessing political leaders is an important task in any country. Citizens should do this in a democracy to help hold their elected representatives to account and to ensure that their voices are heard. Parties should do this carefully to make sure that their electoral prospects are maximised. The questions are ever more important at a time when public disillusionment with politics and the political process has increased. But who have been the great leaders? How can we make a claim that they are ‘great’ objectively and impartially? What can parties and future leaders learn from past successes and mistakes?

In this book we address these questions by focusing on British Labour Party leaders from the time the party was founded up to Ed Miliband. Who was the most successful Labour Party leader of all time? And who was the worst?

If we were to just count general election victories, Harold Wilson comes top, with four. But does this tell the whole story? Clement Attlee frequently comes top of polls of the public, academics and even parliamentarians.2 Tony Blair’s record of three consecutive electoral victories must also put him in good stead. But then there are also the many other forgotten leaders. Take, for example, George Lansbury, who was described by the contemporary left-wing Labour MP Jon Cruddas as the ‘greatest ever Labour leader’.3 And what about Keir Hardie?

Drawing conclusions is made harder because even those leaders we may think of as great have their critics. Winston Churchill described Attlee as ‘a modest man with much to be modest about’.4 Wilson was criticised by Denis Healey for having ‘neither political principal’ nor a ‘sense of direction’.5 Blair is considered a ‘warmonger’ by many on the left for his decision to go to war in Iraq, and as a leader who too readily accepted free-market principles. Beatrice Webb, a contemporary of Lansbury, described Lansbury as having ‘no bloody brains to speak of’.6

THE TWO ‘C’S OF LEADERSHIP: CONSCIENCE AND CUNNING

It is suggested here that there are two overarching ways in which we can try to evaluate leaders. Much confusion comes about because spectators confuse the two approaches or are not explicit about the approach they have in mind and the contradictions between them.

The first approach is to evaluate political leaders in terms of whether they have aims, use methods and bring about outcomes that are principled and morally good. This is defined here as leadership driven by conscience.7 It involves an ethical and normative judgement about whether a leader’s imprint on the world is positive. Leaders are ‘better’, for example, if they strive to reduce poverty, increase economic growth or prevent human suffering; less so if they bring about needless war or economic decline, or fail to improve the lives of the impoverished. A leader led by their conscience will resist opportunities to further their own private position – be it the allure of office, prestige and power – if it is at the detriment of the public good.

Evaluations of Labour leaders in terms of conscience are ever present in discussions of Labour leaders, because of the history of the party. It grew out of the trade union movement and socialist political parties of the nineteenth century to represent the interests of the urban proletariat, some of whom had been newly enfranchised for the first time. The 1900 Labour Party manifesto therefore pledged maintenance for the aged poor, public provision of homes, work for the unemployed, graduated income taxes and more,8 as the party sought to, in Keir Hardie’s later words, bring ‘progress in this country … break down sex barriers and class barriers … [and] lead to the great women’s movement as well as to the great working-class movement’.9 Evaluations of whether leaders aimed to achieve conscience-orientated goals are found in this volume. For example, Kenneth O. Morgan praises Keir Hardie for setting out policy platforms on unemployment, poverty, women’s and racial equality and more. Phil Woolas praises John Robert Clynes for his ‘selfless political ego’ and commitment to improve the lives of millions of impoverished Britons. Brian Brivati heralds Hugh Gaitskell for not treating the Labour Party as ‘a vote-maximising machine’ and considers him to be ‘the last great democratic socialist leader of the Labour Party’.

Many leaders have faced criticism for supposedly deviating from conscience-orientated goals. The Labour Party’s history has been full of accusations of those ‘guilty of betrayal’ to the roots of the party – the workers, unions and voters. These criticisms accumulated as the twentieth century progressed, as the party moved to the centre ground and as leaders accepted economic orthodoxy. During the Second World War, in contempt of the stock and strategy of British politicians on the left, George Orwell blasted that the ‘Labour Party stood for a timid reformism … Labour leaders wanted to go on and on, drawing their salaries and periodically swapping jobs with the Conservatives’.10 These evaluations are well documented in this book. David Howell describes how the decision of Ramsay MacDonald, as Labour Prime Minister, to accept unemployment benefit cuts led to him being demonised for careerism, class betrayal and treachery. Neil Kinnock, as he himself describes in Chapter 20, was roundly criticised for having ‘electionitis’. For the Bennite left, Kinnock was ‘the great betrayer’.11 Even Ed Miliband, who, as Tim Bale suggests, was criticised for being ‘too left-wing’, was condemned for severing the link between the unions and Labour Party. Left Unity accused him of betraying the roots of the party.12 Of course, conscience-orientated criticism has also come from the right. The pursuit of socialist goals might stifle economic opportunity, insist liberals, conservatives and even some social democrats.

A second approach involves assessing leadership in terms of political cunning. This requires us to appraise leaders in terms of whether they are successful in winning power, office and influence. It forces us to introduce a degree of political realism into our evaluations. Leaders operate in a tough, cut-throat environment, where the cost of electoral defeat is usually their job and their party’s prospect of power. To survive, leaders’ goals can never be solely altruistic. They need to win elections and bolster their own position within their party and government if they are to achieve the grander aims they may have first set out in the field of politics to achieve. In trying to achieve policy objectives, they do so in an environment that can be hugely challenging. Some policy goals might have to be dropped as part of horse-trading within Parliament so that other legislation can be passed. ‘Accommodating’ the electorate by dropping policies that are an ‘electoral liability’ might not be heroic in the sense of conscientious leadership, but can be astute leadership in the cunning sense.

There is also a conscience/cunning contradiction at play when we consider the means leaders use to achieve their goals. Those concerned with conscience leadership might not want leaders to be underhand, break promises to the electorate or be disloyal to their parliamentary party or (shadow) Cabinet. But thinking about cunning leadership, we might, at least on occasion, recognise that these are necessary means to other ends if they secure the longer-term goals that we want: that piece of legislation passed to improve social welfare, or establish party discipline so that the party can fight an election on a stronger, united front or compromise with another party to secure a coalition.13 Harriet Harman recounted advice that she was given by Barbara Castle, who explained how she got the Equal Pay Act passed. Wilson’s government, Castle explained, was trying to get a Prices and Incomes Law with the narrowest of parliamentary majorities. Sitting on the front bench when the Speaker was making the roll call, Castle held a gun to her party and told them that ‘unless I get the Equal Pay Act, I am not voting for this’. ‘That is not very teamly, Barbara,’ replied Harman, but she subsequently reflected ‘that sometimes you need to play a little bit rough’.14 Those concerned with conscience leadership might warn us that ‘whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster’.15 But those concerned with cunning leadership warn that politics forces leaders to fight dirty sometimes.

Lastly, there is a conscience/cunning distinction at play when we think about the consequences of political leaders’ periods in office, in terms of whose interests leaders pursue. Those concerned with conscience leadership would demand that leaders should further the interests of the whole polity. They should not put any private interest, such as those of the individual, Cabinet or party, above those of the country.

Those concerned with cunning leadership, however, would champion the importance of furthering the interests of a particular group or section of society. The Labour Party, we should remember – like similar parties forged from the flames of industrialisation across western Europe and much of the rest of world – did not form to promote the general welfare of a nation. It began as a trade union movement to promote the welfare and interests of its own members. These were members of a particular class, based predominantly in manufacturing industries, and invariably those who were exposed to the harshest living and working conditions and absolute poverty. They defined their aims and interests in open opposition to those of employers and landowners. The policies they promoted may have benefited the national interest, but that was not how labour politics was framed.16 Leaders might be successful in maintaining their own position in power – this too would be cunning leadership.

CONSCIENTIOUS VERSUS CUNNING LEADERSHIP

Which is more important? Conscience or cunning leadership?

Our instincts are perhaps that conscience leadership is more important. A perception that leaders endlessly pursue the interest of their party above the country arguably has contributed towards public distrust of politicians, political leaders and politics. Yet the reality of politics is that it does involve compromise and strategy. Evaluating leaders in terms of conscientious leadership alone is therefore obviously problematic.

The case for evaluating leaders in terms of cunning leadership is three-fold.

Firstly, such evaluations are easier to conduct in objective terms. Discussions about what constitutes conscience leadership are inevitably normative and these debates can be conveniently set aside. After all, is the conscience economic policy one that limits environmental degradation or one that promotes economic growth to alleviate poverty? Does it promote state provision of health care or private enterprise? Each of these requires difficult judgements that should be considered in detail elsewhere, and they require the tools of the economist, philosopher and more.

Secondly, nothing can be achieved without power and office. The Labour Party took twenty-four years to be in government after it was founded. It was out of office for eighteen years following James Callaghan’s defeat in 1979. At the time of writing, the party is set to be out of power until at least 2020. During these times of political wilderness, leaders are typically incapable of bringing about progressive social change because of the winner-takes-all nature of British government. It is therefore necessary for political parties who are trying to choose their party leaders and decide upon a future political strategy to think about political leadership in terms of political cunning.

Thirdly, there are also advantages for the citizen of evaluating leaders in this way. If all parties are sufficiently politically competent, then democratic politics should be a more competitive process, giving the voter better choice. As Neil Kinnock remarks in Chapter 20, leaders of the opposition play a vital role in servicing democracy by providing an alternative government.

Moreover, if civil society better understands the challenges leaders face, why they were (un)successful in winning office and how any imperfections and injustices in democratic politics bring about this outcome, then it will be better positioned to prescribe democratic change and support more conscience leaders. Civil society is not always equipped with knowledge about the inner workings of government in the way that elite politicians and parties are. Evaluating leaders in statecraft terms can therefore encourage us to think about the health of democratic politics and to redress any shortcomings. Of the poor leader who still won elections, it makes us think: how did they get away with it? Of the good leader who overcame numerous challenges, it makes us think: how did they manage that?

THE THIRD ‘C’ OF LEADERSHIP: COMPLETE LEADERSHIP

Conscience and cunning leadership are, of course, not mutually exclusive. theoretically, leaders can achieve their conscience goals, means and consequences with political cunning. this is no small feat. to manage a political party, develop policies, pass legislation, outmanoeuvre the opposition and form electoral coalitions when necessary – without compromising conscience goals, using unscrupulous methods or putting personal/party interests above the interests of the nation – might be unfeasible. But, theoretically, it is possible, and we can think of leaders who achieve this as being complete leaders.

FIGURE 1.1: CONSCIENCE, CUNNING AND COMPLETE LEADERSHIP.

There is reason to think that, since the time when the Labour Party was first founded, leaders have been under increased pressure to achieve both conscience and cunning leadership. in 1900, the franchise was limited to men with wealth, and levels of education were comparatively low. A winning electoral strategy could, therefore, be wilfully neglectful of much of the country. Today, Britain is a democracy in which all citizens can vote, and the widespread availability of the press allows ideas to be exchanged and debated. In a democracy, being a conscience-focused leader should therefore deliver you electoral dividends. As Charles Clarke argues in Chapter 3, a general election is, in many ways, a fair test of the leader.

But there are still flaws in British democracy: the media is often thought to have undue influence; electoral laws can give advantage to political parties; corporate power gives uneven political influence; citizens have limited knowledge of and interest in politics and policy; and incumbency gives a government the opportunity to use the state for political purposes. An unscrupulous leader might win office because of these injustices. Convinced that Thatcher was of this ilk, many on the left and in the centre of British politics in the 1980s argued for radical constitutional reform under the rubric of Charter 88.17

THE BOOK AHEAD

Having now introduced the puzzle, in the next chapter of this book, Jim Buller and I introduce a framework for evaluating leaders. This suggests that we should assess leaders by statecraft – the art of winning elections and achieving a semblance of governing competence in office. Not all Labour leaders were prime ministers – some did not stay in power long enough to fight a general election, and, for others, winning office was never likely. But we can still assess them in terms of whether they moved their party in a winning direction. The statecraft approach also defines the key tasks leaders need to achieve in order to win elections. This is helpful because it allows us to consider where they might have gone wrong. The approach focuses firmly on cunning leadership.

After the statecraft framework is outlined in Chapter 2, Charles Clarke then evaluates the success (or otherwise) of Labour Party leaders at election time in Chapter 3. Using data on the seats and votes that they have won or lost, he compiles league tables to identify those who have been successful and those who have not. This chapter therefore gives us an important overview of the electoral fortunes of Labour leaders since the party was founded.

Subsequent chapters then provide individual assessments of each of the Labour leaders. The authors of each chapter are all leading biographers of their subject. Biographers were deliberately invited to contribute towards the volume as they can paint a picture of the context of the times and the political circumstances in which their subject was Labour leader. The biographers were not asked to directly apply the statecraft approach, but to describe their leader’s background on the path towards the top position, as well as the challenges the leader faced and how successful they were in electoral terms. Many assessments go beyond examining the political cunning of leadership and also include judgements in conscience terms. They therefore, collectively, provide a rich set of evaluations from leading scholars and commentators.

Table 1.1 provides a summary of the authors’ (though not necessarily the editors’) assessments in statecraft terms. Many of the early leaders were deemed to be a success. Keir Hardie is praised for being a pragmatic strategist who concentrated political efforts on increasing Labour representation in Parliament, which in turn laid the road to power. John Robert Clynes was at the helm for the great breakthrough in 1922; Ramsay MacDonald was the first to win office. Of the modern leaders, Harold Wilson, argues Thomas Hennessey, has an almost unrivalled electoral record, while Tony Blair, asserts John Rentoul, had an intuitive feel for public opinion, possessed natural communication skills and devised a successful winning electoral strategy.

Gaitskell, Callaghan, Foot, Brown and Miliband, the biographers generally accept, were failures in statecraft terms. Claims for success, if there are any, instead lie largely in conscience terms (in the case of Gaitskell and Foot), or in their contribution before they were leader (in the case of Callaghan and Brown).

Clement Attlee is perhaps a surprise inclusion in those leaders who are given a more mixed assessment. Nicklaus Thomas-Symonds provides a robust argument in favour of Attlee in conscience terms – it was under Attlee that the modern welfare state and the National Health Service were created – but argues that Attlee failed to provide leadership on issues such as the devaluation crisis of 1949, and that he had a naive approach to the electoral boundaries, which undermined his statecraft.

TABLE 1.1: LABOUR LEADERS’ STATECRAFT SUCCESS AND FAILURES, 1900–2015.

GreatMixedPoorKeir Hardie John Robert Clynes Ramsay MacDonald Harold Wilson Tony BlairGeorge Nicoll Barnes William Adamson Arthur Henderson George Lansbury Clement Attlee Neil Kinnock John SmithHugh Gaitskell James Callaghan Michael Foot Gordon Brown Ed MilibandIn the final chapters, we take an original approach by asking the leaders for their own perspectives on leading the Labour Party. The book therefore includes two exclusive original interviews: Neil Kinnock, who led the Labour Party 1983–92; and Tony Blair, leader 1994–2007. In the interviews, we ask them about their path towards the office of leader, the challenges they faced, whether they think the statecraft framework is a ‘fair’ test of a leader, and how they would rate themselves using that model. These interviews are of important historical value for those wanting to understand past leaders’ tenures. They also provide lessons for future leaders. Moreover, they allow practitioners of politics to join in the conversation with academics, whose ideas might otherwise be left in ‘ivory towers’. This type of conversation can only improve our understanding of the quality of leadership and leaders’ understanding of the scholarship on it.

1 Thomas Carlyle, ‘The Hero as Divinity’, in Heroes and Hero-Worship, London, Chapman & Hall, 1840. Carlyle’s quote obviously implicitly embodied the discriminatory assumption about the role of women in history. Sadly, there have been no female Labour leaders yet.

2 See Charles Clarke’s discussion of such polls in Chapter 3.

3 Jon Cruddas, ‘George Lansbury: the unsung father of blue Labour’, Labour Uncut, 5 August 2011, accessed 29 May 2015 (http://labour-uncut.co.uk/2011/05/08/george- lansbury-the-unsung-father-of-blue-labour).

4 Cited in Chris Wrigley, Winston Churchill: A Biographical Companion, Santa Barbara, CA, ABC Clio Inc., 2002, p. 32.

5 Cited in Kevin Hickson, The IMF Crisis of 1976 and British Politics, London, Tauris Academic Studies, 2005, p. 48–9.

6 See Chapter 9.

7 This discussion builds on the distinction made by Joseph Nye, The Powers to Lead, Oxford and New York, Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 111–14.

8 The Labour Party, ‘The Labour Party General Election Manifesto 1900: Manifesto of the Labour Representation Committee’, in Iain Dale ed., Labour Party General Election Manifestos, 1900–1997, London, Routledge, 2000, p. 9.

9 Keir Hardie, ‘The Sunshine of Socialism’, speech delivered at the twenty-first anniversary of the formation of the Independent Labour Party in Bradford, 11 April 1914, accessed 29 May 2015 (http://labourlist.org/2014/04/ keir-hardies-sunshine-of-socialism-speech-full-text).

10 George Orwell, The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius. Part 3: The English Revolution, London, Secker & Warburg, 1941.

11 Francis Beckett, ‘Neil Kinnock: the man who saved Labour’, New Statesman, 25 September 2014.

12 Bianca Todd, ‘Labour has betrayed its roots by distancing itself from the unions’, The Guardian, 3 March 2014, accessed 29 May 2015 (http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/mar/03/ labour-party-unions-left-unity-ed-miliband).

13 Cunning leadership does not necessarily require deceit – but cunning leaders should not be criticised for using it. The contemporary meaning of the word ‘cunning’ does imply dishonesty. The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as ‘skill in achieving one’s ends by deceit’. As the same dictionary notes, however, this was not always the case. The term has its origins in Middle English (‘cunne’) and the original sense of the word had no implication of deceit – it implied knowledge and skill. Source: Angus Stevenson, Oxford English Dictionary (third edition), Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2010.

14 Harriet Harman, ‘Harriet Harman in conversation with Charles Clarke’, lecture at the University of East Anglia, 22 January 2015 (http://www.ueapolitics.org/2015/01/23/ harriet-harman/).

15 Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, New York, Random House, 1966 [1886], sec. 146.

16 Over time, of course, the party evolved to develop a broader appeal as class cleavages were perceived to have declined. Ed Miliband rebranded the party as ‘One Nation Labour’ in 2012. See: Roy Hattersley and Kevin Hickson. The Socialist Way: Social Democracy in Contemporary Britain. London, I. B. Tauris, 2013, p. 213.

17 David Erdos, ‘Charter 88 and the Constitutional Reform Movement Twenty Years On: A Retrospective’, Parliamentary Affairs, 64(4), 2009, pp. 537–51; Mark Evans, Charter 88: Successful Challenge to the British Political Tradition?, Aldershot, Dartmouth, 1995.

CHAPTER 2

STATECRAFT: A FRAMEWORK FOR ASSESSING LABOUR PARTY LEADERS

TOBY S. JAMES AND JIM BULLER

Assessing party leaders is not an easy task. In this chapter, Toby S. James and Jim Buller discuss the challenges that we face in trying to do so, and suggest a framework that can be used. Leaders can be assessed in terms of how well they practise statecraft – the art of winning elections and demonstrating a semblance of governing competence to the electorate. Practising statecraft involves delivering on five core tasks. They need to: devise a winning electoral strategy; establish a reputation for governing competence; govern their party effectively; win the battle of ideas over key policy issues; and manage the constitution so that their electoral prospects remain intact. This chapter outlines what these tasks involve and considers some of the contextual factors that might make them more or less difficult to achieve.

• • •

The British Labour Party has seen many electoral highs and lows during its long history.

Clement Attlee’s 1945 landslide general election victory will rank, for many at least, as the greatest moments. The result came as a great shock because of Winston Churchill’s heroic status, but Attlee led the party to a 146-seat majority and the greatest Labour vote ever recorded at that moment in time. James Chuter Ede, who later became Attlee’s Home Secretary, said that he ‘began to wonder if I should wake up to find it all a dream’ when he heard the results coming in over the radio.18 The King, when asking Attlee to form a government, was struck that Attlee himself was ‘very surprised that his party had won’.19 Meanwhile, the Daily Herald and Daily Worker proclaimed the result as the ‘People’s Victory’ that would ‘stand out for all time as a great act of leadership in the building of the peace’.20 Subsequent historians considered the election to be ‘one of the most important turning points in modern British political history, comparable with the events of 1832 and 1906’.21

And the worst moment? That might be well epitomised by the moment on the afternoon of Wednesday 28 April 2010 when Gordon Brown hid his face with one hand in a live interview on BBC radio. He was listening to a clip in which he described a former Labour voter whom he had met that day, Gillian Duffy, as a ‘bigoted woman’, unaware that he was being recorded. Gordon Brown described himself as mortified. The effect of this particular incident on the polls was probably negligible, but the media took it as symbolic of a complete divorce between the leader and the grass-roots Labour voter. Arguably, one of Labour’s greatest electoral defeats followed. Only 18.9 per cent of the registered electorate voted Labour – the lowest recorded percentage since 1918, when the party was only becoming established as a major force in British politics.22

As Figure 2.1 shows, however, there have been many other moments of euphoria and despair. An observer, writing in the early 1980s, neatly summarised the party’s electoral history as ‘fifty years forward, thirty years back’. At about that time, the great historian Eric Hobsbawm was writing of ‘the forward march of Labour halted’.23 The Labour Party’s electoral fortunes improved though during the 1990s, peaking in 1997, only to then decline again – although not before the party had governed the UK for thirteen consecutive years as New Labour, dominating party politics.

FIGURE 2.1: THE LABOUR PARTY’S VOTE SHARE AND SEAT SHARE IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONS AT GENERAL ELECTIONS, 1900–2015.

Source: Authors, based on information in Rallings and Thrasher, British Electoral Facts (London, Total Politics, 2006), pp. 3–58, 59, 61–2, 85–92; ‘Election 2010: National Results’, BBC News, accessed 3 December 2014 (http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/election2010/results/); ‘Election 2015: Results’, BBC News, accessed 1 June 2015 (http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/election/2015/results).

Note: ‘Vote share’ is calculated in this figure as the number of votes received as a percentage of total registered citizens (not all votes cast).

PARTY LEADERS MATTER

It is natural for observers to blame or credit the party leader of the time for changing fortunes. Britain has a parliamentary system of government in which citizens vote for a local parliamentary candidate to represent their constituency in the House of Commons. They do not directly vote for a president. Knowing little about their local candidates, however, voters commonly use the party leaders as cues for whom to vote for. Moreover, as time has passed, the powers of party leaders have grown. Both as Prime Minister or Leader of the Opposition, party leaders have played an increasing role in shaping the direction of the party. They have become more important in shaping policy, making appointments within the party and articulating the party’s key message.

Assessing party leaders is therefore important. A party leader without the communication skills necessary to present their vision could mean vital public policies are never implemented. A leader who fails to end party divisions could leave their party out of power for a generation. A leader who makes key strategic errors could see national interest hindered or damaged.

THE DIFFICULTIES OF ASSESSING POLITICAL LEADERS

Assessing political leaders, however, is not easy. There are at least three problems that must be faced.

Firstly, it is just a subjective process, in which we will all have our favourites. Can even the most detached observer really claim to make objective, scientific judgements about who was ‘best’, or will our own political views and values prevent us making a fair assessment? For example, could a left-leaning observer ever recognise Margaret Thatcher’s leadership qualities, or a right-leaning one acknowledge the achievements of Clement Attlee? The benchmarks for success and failure are not clear unless we nail down some criteria; ideological disagreement will always get in the way.

Secondly, who is the Labour leader in question anyway? During the early years of the Labour Party, for example, there was no formal position of leader – leadership came more from the chairman. So who should be the focus of our analysis then? There is a bigger problem, too. Assessing the party leader implies that the focus should be on assessing one single person. Leadership is often, however, a task discharged by more than one individual. A single individual will not have the time and resources to manage a party alone, therefore they will always rely on key advisors or allies. This is not to suggest that a party leader will make all decisions entirely collegially with their (shadow) Cabinet, but there is a case for evaluating the leadership of a small group of two or three individuals who act in a united way, rather than just one person.

Thirdly, aren’t leaders’ fortunes influenced by whether they have to govern in difficult or favourable times? The political scientist James MacGregor Burns claimed that some US presidents were capable of transformative leadership: a great President could redesign perceptions, values and aspirations within American politics.24 But is this always possible during times of economic crisis, party division or war? Do leaders really steer events or are they casualties of them? Are they like ships being crashed around on the waves during a storm? Or is the test of a leader their ability to successfully navigate through such waters? No two leaders are in power at the same time, so direct comparison is impossible. Context is important, however.

Certainly, closer analysis of the circumstances of Attlee’s 1945 general election victory requires us to re-assess him. Many historians have argued that 1945 was a moment at which the popular mood changed. Ralph Miliband argued that the war ‘caused the emergence of a new popular radicalism, more widespread than at any time in the previous hundred years’, which was ‘eager for major, even fundamental change in British society after the war’.25 The public found itself decisively pro-Soviet because of the wartime media coverage.26 The Labour Party, argued the historian Henry Pelling, benefited from securing credit for the Beveridge Report, but this was somewhat accidental.27 Meanwhile, the Conservative Party was said to be tired and disorganised, with Churchill making many presentational mistakes.28 The historian Robert Pearce has gone so far as to suggest that victory, therefore, ‘owed little to Attlee’.29

Closer analysis of the circumstances of Brown’s 2010 general election defeat requires us to re-assess him as well. Brown inherited an unpopular party after it had been in government for ten years, and he himself had only been in power for a few months before the global financial crisis of 2007/08 – considered by many economists to have been the worst crisis since at least the Great Depression hit Britain.30 The economy was sent into recession, and Brown, who had worked to establish a reputation as the ‘Iron Chancellor’, was faced with very difficult waters from which to rescue the party’s reputation for economic management.31

We could go on. Michael Foot is commonly derided by contemporaries for his electoral strategy in the 1983 general election. His manifesto was immortalised as ‘the longest suicide note in history’ by Labour MP Gerald Kaufman. But could any Labour leader have defeated Thatcher in 1983 on the back of the Falklands War and an upswing in the economy? Factoring in such circumstances is clearly important when we make judgements about Labour leaders.

A STATECRAFT APPROACH

A clear framework is necessary to assess leaders. One way of providing an assessment is to evaluate Labour leaders on whether or not they were successful in achieving statecraft, which is the art of winning elections and maintaining power.32

No doubt, many leaders will want to achieve more than this. They may be concerned about their legacy – how they are viewed by future generations – or driven by a desire to implement policies that they think will improve the good of their party and people. However, none of the latter is possible without first having office. Without office, they may not remain as party leader for long, due to the cut-throat nature of politics. General election defeats inevitably come with leadership challenges and expectations of resignation.

So how can we assess Labour leaders’ success in winning office? The simplest approach would be to count the number of elections that they fought, the number they won and the number they lost. This is indicative, but only takes us so far. A more detailed approach involves looking at what things political leaders need to achieve in order to accomplish the goal, and then evaluating them by each of these functions. The statecraft approach argues that leaders need to achieve five tasks; each of them is outlined below.

Yet, as has already been alluded to, some leaders are gifted more fortunate circumstances than others when trying to win elections for their party. We have argued elsewhere that the context in which leaders find themselves must be factored into our assessments of them. This is not an easy task either, however.

Can we realistically say, for example, that Clynes’s circumstances were twice as easy as Lansbury’s? Or Foot’s twice as hard as Attlee’s? Given that leaders operate in different historical moments, qualitatively different in kind, quantitative measurement is difficult. The circumstances that leaders face are also different for each individual. A Labour leader who has already been Chancellor, like Brown, is always going to have a very different experience of trying to establish governing competence on the economy to one who has not held such a position.33

Nonetheless, to aid discussion, Table 2.1 lists some of the contextual factors that might be important and these will be unpacked under each statecraft task considered next.

TABLE 2.1: CONTEXTUAL FACTORS TO BE CONSIDERED WHEN ASSESSING LEADERS.

Statecraft taskContextual factorsWinning electoral strategyParty resources and campaign infrastructure Unfavourable electoral laws (constituencies, election administration, electoral system, party finance) Partisan alignment of the press Ability to call election when polls are favourableGoverning competenceParty reputation Conditions for successful economic growth Foreign policy disputes Time in officeParty managementPresence of credible rival leaders Rules for dethroning Levels of party unity Available mechanisms for party discipline Time in officePolitical argument hegemonyIdeological developments at the international level Alignment of the press Available off-the-shelf strategies in the ‘garbage can’ Developments in the party system Time in officeBending the rules of the gamePresence of policy triggers or favourable conditions to enact (or prevent) changeWINNING ELECTORAL STRATEGY

Firstly, leaders need to develop a winning electoral strategy by crafting an image and policy package that will help the party achieve the crucial impetus in the lead-up to the polls. Opinion polls, and, to some extent, local/European election results, give a very good indication of how a party is faring in the development of a winning strategy, and allow a party leader’s fortunes to be charted over time – although this information is not always as readily available for the earlier Labour leaders, when polling was more infrequent or did not take place at all.

In developing a winning strategy, the leader will need to pay close attention to the interests of key segments of the population, whose votes might be important in gaining a majority. Leaders may need to respond to transformations in the electoral franchise, demography or class structure of society, and build new constituencies of support when necessary. These changes can often advantage a leader. The extensions of the franchise in the Representation of the People Act 1918, for example, tripled the electorate to include more working-class voters. This had the potential to turn electoral politics upside down in Labour’s favour.

It is not just a matter of getting more votes than the opposition, however, because the distribution of votes is just as important. Labour’s high-water mark of votes came under Attlee in the 1951 general election, but the party ironically lost power to the Conservatives in that election, who had recorded fewer votes. The February 1974 general election saw Harold Wilson win fewer votes than his opponent Edward Heath, but more seats. A winning electoral strategy therefore takes this into consideration.

This point highlights how electoral laws can make it easier or more difficult for leaders to win power. While Attlee may have felt cheated in 1951, the first-past-the-post electoral system has usually advantaged the Labour Party in the post-war period. It has reduced the chances of new parties entering the political system and has given them and the Conservatives a disproportionately high share of seats in the House of Commons for their proportion of the popular vote, as Figure 2.1 illustrated. The way in which the constituency boundaries are drawn has periodically conferred a systematic advantage on the party, but not always. In modern times, the system benefited the Conservatives from 1950 to 1966, had a net bias close to zero from then until 1987, and has favoured the Labour Party until 2015.34