1,90 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Lebooks Editora

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

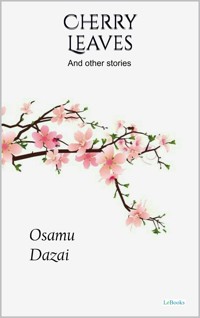

Cherry Leaves and Other Stories is a poignant collection that captures the fragility of human emotions, the weight of memory, and the quiet beauty found in fleeting moments. In these short narratives, Osamu Dazai blends lyrical prose with an unflinching gaze into the vulnerabilities of ordinary lives, often revealing the undercurrents of loneliness, longing, and impermanence that shape human experience. Set against the backdrop of postwar Japan, the stories reflect a society negotiating its scars while seeking fragments of solace and meaning. Through a delicate balance of melancholy and wit, Dazai presents characters whose struggles—whether with love, family ties, or personal identity—mirror universal human concerns. His portraits of everyday life are imbued with a sensitivity that elevates small gestures and passing encounters into moments of quiet significance. Each story, like a fallen cherry leaf, holds a trace of beauty and decay, inviting contemplation on the transient nature of happiness and the inevitability of change. Since its publication, Cherry Leaves and Other Stories has been celebrated for its refined emotional depth and understated elegance. Its enduring appeal lies in Dazai's ability to intertwine personal sentiment with broader reflections on life's fragility, offering readers not only glimpses into postwar Japanese sensibilities but also timeless meditations on love, loss, and resilience. By distilling life's complexities into deceptively simple vignettes, the collection continues to resonate, reminding us of the profound truths hidden within life's most fleeting moments.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 127

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Osamu Dazai

CHERRY LEAVES AND OTHER STORIES

Contents

INTRODUCTION

CHERRY LEAVES AND THE WHISTLER

DECEMBER 8

WAITING

ONE SNOWY NIGHT

LA FEMME DE VILLON

OSAN

AN ENTERTAINING LADY

INTRODUCTION

Osamu Dazai

1909 – 1948

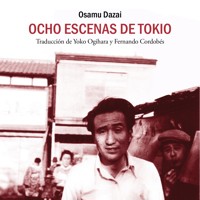

Osamu Dazaiwas a Japanese novelist, widely regarded as one of the most significant literary figures of 20th-century Japan. Born in Kanagi, Aomori Prefecture, Dazai is best known for his works that explore themes of alienation, self-destruction, and the search for meaning in a rapidly modernizing society. His deeply personal and often semi-autobiographical narratives reflect the turmoil of his own life, marked by repeated suicide attempts and a profound sense of existential despair. Today, his novels No Longer Human (1948) and The Setting Sun (1947) stand as classics of modern Japanese literature.

Early Life and Education

Osamu Dazai, born Shūji Tsushima, was the eighth child of a wealthy landowning family. Despite his privileged background, he felt alienated from his family and community from an early age. His upbringing was strict, and he struggled to connect with his authoritarian father and the expectations of his class. Dazai studied French literature at the University of Tokyo but never graduated, as his life began to spiral into instability due to personal and financial troubles, substance abuse, and his growing obsession with literature. During his youth, he became heavily influenced by Western writers such as Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Anton Chekhov, and Franz Kafka, as well as by the Japanese I-novel tradition, which favored confessional, autobiographical storytelling.

Career and Contributions

Dazai’s work is characterized by its confessional style, blending fiction and autobiography to the point where the boundaries between the two become blurred. His writing often depicts disillusioned and self-destructive protagonists, mirroring his own struggles with depression and addiction. In The Setting Sun, Dazai portrays the decline of the Japanese aristocracy in the aftermath of World War II, capturing a nation in moral and social transition. No Longer Human, considered his masterpiece, is a haunting account of a man incapable of conforming to societal norms, descending into isolation and despair—a reflection of Dazai’s own inner turmoil.

His short stories, such as Run, Melos! and Schoolgirl, reveal his versatility, ranging from allegorical retellings of classical myths to sensitive portrayals of youthful innocence. Through his unique voice, Dazai merged traditional Japanese narrative elements with Western literary influences, creating a body of work that remains distinct in both tone and subject matter.

Impact and Legacy

Dazai’s work resonated deeply with postwar Japan, a society grappling with the collapse of its traditional values and the trauma of defeat. His candid exploration of human weakness, self-doubt, and alienation spoke to a generation struggling to find meaning in a changing world. His style, marked by irony, humor, and pathos, has influenced countless Japanese authors, including Yukio Mishima and Haruki Murakami.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Dazai’s appeal endures strongly among younger readers, who find in his works an intimate reflection of personal insecurity and existential struggle. Internationally, his novels have gained recognition for their universal themes, and translations have introduced his voice to readers around the world.

On June 13, 1948, Dazai and his lover Tomie Yamazaki committed double suicide by drowning in the Tamagawa Canal in Tokyo. He was only 38 years old. His tragic death cemented his image as a romantic, tormented artist, forever linked to the confessional nature of his works.

Although his career was brief, Osamu Dazai left a lasting mark on Japanese literature. His ability to confront the darkness of the human psyche with honesty and lyricism ensures his place as one of Japan’s most compelling literary voices. His novels continue to be read, studied, and adapted, maintaining their relevance as timeless meditations on the fragility of identity and the struggle to belong.

About the work

Cherry Leaves and Other Stories is a poignant collection that captures the fragility of human emotions, the weight of memory, and the quiet beauty found in fleeting moments. In these short narratives, Osamu Dazai blends lyrical prose with an unflinching gaze into the vulnerabilities of ordinary lives, often revealing the undercurrents of loneliness, longing, and impermanence that shape human experience. Set against the backdrop of postwar Japan, the stories reflect a society negotiating its scars while seeking fragments of solace and meaning.

Through a delicate balance of melancholy and wit, Dazai presents characters whose struggles—whether with love, family ties, or personal identity—mirror universal human concerns. His portraits of everyday life are imbued with a sensitivity that elevates small gestures and passing encounters into moments of quiet significance. Each story, like a fallen cherry leaf, holds a trace of beauty and decay, inviting contemplation on the transient nature of happiness and the inevitability of change.

Since its publication, Cherry Leaves and Other Stories has been celebrated for its refined emotional depth and understated elegance. Its enduring appeal lies in Dazai’s ability to intertwine personal sentiment with broader reflections on life’s fragility, offering readers not only glimpses into postwar Japanese sensibilities but also timeless meditations on love, loss, and resilience. By distilling life’s complexities into deceptively simple vignettes, the collection continues to resonate, reminding us of the profound truths hidden within life’s most fleeting moments.

CHERRY LEAVES AND THE WHISTLER

When the cherry blossoms have scattered and new leaves sprout on the trees, I am reminded of that time. Thirty-five years ago, my father was still alive, and our family — if one could call it that, with my mother having passed away seven years earlier when I was thirteen, leaving only my father, my younger sister, and me — lived on the outskirts of a castle town in Shimane Prefecture. This place was located on the Japan Sea coast and had a population of about twenty thousand. Father accepted a position as headmaster of a middle school there when I was eighteen and my sister was sixteen. However, since no suitable lodgings were available in town, we rented two rooms in a house on the grounds of a temple near the foot of a mountain. We lived there for six years until Father was transferred to a middle school in Matsue. I didn't marry until after we moved to Matsue in the fall of my twenty-fourth year, which, in those days, was quite late for a girl. With Mother having died so young, and with Father being so absorbed in his scholarly work and out of touch with worldly matters, I knew our household would fall apart if I left. Though I’d received several offers over the years, I didn't want to marry if it meant abandoning my family. If my sister had been healthy, I would have felt more inclined to do as I pleased. However, although she was a lovely and intelligent child with long, beautiful hair, she was physically infirm. In the spring of the second year after my father took up his post in the castle town, she died. This is the story of something that happened shortly before her death.

She had been in very poor health for quite some time by then. She had renal tuberculosis, a terribly serious disease, and both of her kidneys had been severely damaged before it was detected. The doctor told Father quite bluntly that she would die within a hundred days and explained that there was nothing he could do. Of course, there was nothing we could do either, but watch in silence as one month passed, then another, and even as the hundredth day approached. Not knowing how close to death she was, my sister remained in relatively good spirits. Though confined to bed day and night, she sang songs, joked, and laughed as I spoiled her. Whenever I reflected on her having only thirty or forty days to live — a medical certainty — it was as if needles were piercing my entire body, and I thought I would go mad with the pain. March, April, May…yes, it was the middle of May. It's a day I'll never forget.

The meadows and mountains were covered with fresh greenery, and it was warm enough to want to shed one’s clothing. The new greenery was so brilliant in the sunlight that it stung my eyes as I walked along a meadow path. My head was bent, and I had one hand tucked in my sash. I was turning this and that over in my mind. My thoughts were so painful that I was soon literally trembling and finding it difficult to breathe. Suddenly, an eerie, booming, otherworldly sound came from deep beneath the verdant earth at my feet. It was faint yet enormous, like giant drums being beaten in hell below — a steady, unbroken rumbling. Not knowing what that horrifying sound might be, I wondered if I had finally lost my mind. I stood frozen until I could no longer stand and, with a cry of anguish, collapsed in the long grass. I wept and wept.

I later learned that the strange, terrifying sound had been the cannons of warships under Admiral Togo’s command. They were engaged in the battle that would sink the entire Russian Baltic fleet. Navy Day is just around the corner again, isn't it? You see, all of this happened right at that time. In that castle town by the sea, everyone must have been in mortal fear hearing the rumble of those cannons. Not knowing what they were, and half mad with concern for my sister, I believed I was hearing the drums of the netherworld. I sat in the meadow for a very long time, sobbing and too afraid to lift my eyes. It wasn't until evening began to fall that I finally stood up and walked, in a deathlike trance, back to the temple.

My sister called to me when I arrived home. She was terribly thin and weak by now, and it seemed that she was beginning to realize she didn’t have long to live. She no longer asked me to cater to her whims or mother and spoil her. That made it all the more painful for me.

"When did this letter come?" she asked.

Her question startled me so much that I felt the blood drain from my face.

"When did it come?" she asked again, innocently.

I pulled myself together and replied, "Just a while ago. While you were sleeping. You were smiling in your sleep. I put it there by your pillow. You didn't notice, did you?"

"No, I didn't." Darkness was falling, and her smile was pale and beautiful in the dim light of the room. "I read the letter, though. It’s so strange. I don’t know this person.”

"Oh, you don't, don't you?" I thought. I knew who the sender was — a man who called himself "M.T." Oh, I knew who he was all right. I’d never met him, but five or six days earlier, I’d been rearranging my sister’s wardrobe when I found a bundle of letters tied with a green ribbon in the bottom of a drawer. I suppose it wasn’t the right thing to do, but I untied the ribbon and looked at the letters. There were about thirty of them, all from Mr. M.T. His name and return address weren't written on the envelopes, but he signed all of them. The envelopes had the names of various girls, all of whom were my sister's friends. My father and I never dreamed that she was carrying on such voluminous correspondence with a man.

This M.T. must have been a cautious fellow who asked my sister for the names of her friends so he could write to her without arousing suspicion. Having deduced that much, I marveled at the boldness of youth. It was enough to make me shudder with fear just to imagine what would happen if our stern and severe father were to find out. But when I began reading the final letter, written the previous fall, I suddenly leaped to my feet. It was perhaps like being struck by lightning; I stood bolt upright with the shock. My sister’s romance had not been purely platonic; it had progressed to more detestable things.

I burned every single letter. As far as I could gather, M.T. was an impoverished poet living in the town — and a coward, having abandoned my sister as soon as he learned of her illness. The final letter contained the cruelest things written in the most offhand, breezy way — saying how they should try to forget each other and so on — and he hadn't written again since then, apparently.

I realized that if I kept what I’d discovered to myself, my sister could remain pure and unsullied until the end. No one knows, I told myself. This breast alone shall bear the torment. However, learning the truth only made me pity my sister more. I imagined all sorts of outrageous things, and I felt a bittersweet ache in my heart — a suffocating, unbearable feeling that only a girl coming of age could understand. It was a living hell, and I suffered alone as if I had that dreadful experience. I was not quite myself in those days.

"Read it to me, won't you?" she said. "I haven't the slightest idea what it's all about."

Her dishonesty at that moment repulsed me.

"Are you sure it's all right?" I asked quietly, my fingers trembling as I took the letter. I knew what it said without opening and reading it. But I had to pretend otherwise. I read it aloud, barely glancing at the pages.

Today, I must ask for your forgiveness. My lack of self-confidence is the only thing that has kept me from writing sooner. I am a poor, powerless man. There is nothing I can do to help you. All I have to offer are words. They contain no falsehoods, but they are still only words. I began to hate myself for my powerlessness and my inability to offer anything more as proof of my love for you. I haven't forgotten you for a single moment, not even in my dreams. But I can do nothing for you. It was this realization that caused me to decide we must part ways. The greater your misfortune and the deeper my love for you, the more difficult it was for me to approach you. Can you understand that? You mustn't think I'm making excuses. I believed I was doing the right thing. But I was mistaken. I know now that I was wrong. Please forgive me. In my selfishness, I only wanted to be the ideal man for you. We are solitary, powerless creatures. However, I now believe that by offering these faithful, honest, and inadequate words, I can hope to live a life of truth, humility, and beauty. The importance of my offering is not the issue. Is a single dandelion all I have to give you? Then I will send it to you without shame. I realize now that this is the more courageous and manly attitude. I will not run from you again. I love you. Every day, I will write you a poem and send it to you. I'll also stand outside your garden fence and whistle each day. I'll be there tomorrow evening at six o'clock, whistling "The Warship March." I'm a good whistler, you know. This much I can easily do. But don't laugh at me. No, on second thought, please do laugh at me. Be happy. God is surely watching over us somewhere. I believe that. You and I are both his children. We're bound to have a wonderful marriage.

I waited and waited

to see the peach trees in bloom this year.

the peach trees this year.

I heard they’d be white.

But these flowers are crimson.

I’m working hard on my studies.

Everything is going well. Until tomorrow,

— M.T.