1,90 €

Mehr erfahren.

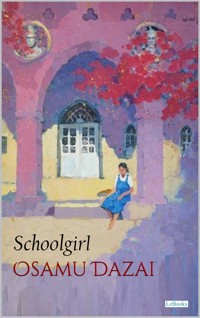

- Herausgeber: Lebooks Editora

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Schoolgirl is a poignant exploration of youth, identity, and the alienation experienced in early 20th-century Japan. Osamu Dazai delves into the inner world of a young girl grappling with the expectations of society and the confusion of adolescence. Through the fragmented diary entries and reflections of the unnamed protagonist, the story reveals themes of loneliness, the search for meaning, and the struggle to reconcile individual desires with societal pressures. Since its publication, Schoolgirl has been praised for its intimate and confessional style, which offers a raw and honest portrayal of a young woman's emotional landscape. Dazai's ability to capture the subtle nuances of teenage anxiety and existential questioning has secured the work's place as a significant piece in Japanese modernist literature. The narrative's introspective tone and focus on the protagonist's psychological depth invite readers to empathize with the universal challenges of growing up. The enduring significance of Schoolgirl lies in its reflection on the fragility of youth and the complexities of self-awareness in a rapidly changing world. By illuminating the tensions between personal freedom and social conformity, the novella encourages readers to consider the silent struggles behind outward appearances and the profound impact of societal expectations on individual identity.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 171

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Osamu Dazai

SCHOOLGIRL

Original Title:

“女生徒 [Joseito]”

Contents

INTRODUCTION

SCHOOLGIRL

INTRODUCTION

Osamu Dazai

1909 – 1948

Osamu Dazaiwas a Japanese novelist, widely regarded as one of the most significant literary figures of 20th-century Japan. Born in Kanagi, Aomori Prefecture, Dazai is best known for his works that explore themes of alienation, self-destruction, and the search for meaning in a rapidly modernizing society. His deeply personal and often semi-autobiographical narratives reflect the turmoil of his own life, marked by repeated suicide attempts and a profound sense of existential despair. Today, his novels No Longer Human (1948) and The Setting Sun (1947) stand as classics of modern Japanese literature.

Early Life and Education

Osamu Dazai, born Shūji Tsushima, was the eighth child of a wealthy landowning family. Despite his privileged background, he felt alienated from his family and community from an early age. His upbringing was strict, and he struggled to connect with his authoritarian father and the expectations of his class. Dazai studied French literature at the University of Tokyo but never graduated, as his life began to spiral into instability due to personal and financial troubles, substance abuse, and his growing obsession with literature. During his youth, he became heavily influenced by Western writers such as Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Anton Chekhov, and Franz Kafka, as well as by the Japanese I-novel tradition, which favored confessional, autobiographical storytelling.

Career and Contributions

Dazai’s work is characterized by its confessional style, blending fiction and autobiography to the point where the boundaries between the two become blurred. His writing often depicts disillusioned and self-destructive protagonists, mirroring his own struggles with depression and addiction. In The Setting Sun, Dazai portrays the decline of the Japanese aristocracy in the aftermath of World War II, capturing a nation in moral and social transition. No Longer Human, considered his masterpiece, is a haunting account of a man incapable of conforming to societal norms, descending into isolation and despair — a reflection of Dazai’s own inner turmoil.

His short stories, such as Run, Melos! and Schoolgirl, reveal his versatility, ranging from allegorical retellings of classical myths to sensitive portrayals of youthful innocence. Through his unique voice, Dazai merged traditional Japanese narrative elements with Western literary influences, creating a body of work that remains distinct in both tone and subject matter.

Impact and Legacy

Dazai’s work resonated deeply with postwar Japan, a society grappling with the collapse of its traditional values and the trauma of defeat. His candid exploration of human weakness, self-doubt, and alienation spoke to a generation struggling to find meaning in a changing world. His style, marked by irony, humor, and pathos, has influenced countless Japanese authors, including Yukio Mishima and Haruki Murakami.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Dazai’s appeal endures strongly among younger readers, who find in his works an intimate reflection of personal insecurity and existential struggle. Internationally, his novels have gained recognition for their universal themes, and translations have introduced his voice to readers around the world.

On June 13, 1948, Dazai and his lover Tomie Yamazaki committed double suicide by drowning in the Tamagawa Canal in Tokyo. He was only 38 years old. His tragic death cemented his image as a romantic, tormented artist, forever linked to the confessional nature of his works.

Although his career was brief, Osamu Dazai left a lasting mark on Japanese literature. His ability to confront the darkness of the human psyche with honesty and lyricism ensures his place as one of Japan’s most compelling literary voices. His novels continue to be read, studied, and adapted, maintaining their relevance as timeless meditations on the fragility of identity and the struggle to belong.

About the work

Schoolgirl is a poignant exploration of youth, identity, and the alienation experienced in early 20th-century Japan. Osamu Dazai delves into the inner world of a young girl grappling with the expectations of society and the confusion of adolescence. Through the fragmented diary entries and reflections of the unnamed protagonist, the story reveals themes of loneliness, the search for meaning, and the struggle to reconcile individual desires with societal pressures.

Since its publication, Schoolgirl has been praised for its intimate and confessional style, which offers a raw and honest portrayal of a young woman’s emotional landscape. Dazai’s ability to capture the subtle nuances of teenage anxiety and existential questioning has secured the work's place as a significant piece in Japanese modernist literature. The narrative’s introspective tone and focus on the protagonist’s psychological depth invite readers to empathize with the universal challenges of growing up.

The enduring significance of Schoolgirl lies in its reflection on the fragility of youth and the complexities of self-awareness in a rapidly changing world. By illuminating the tensions between personal freedom and social conformity, the novella encourages readers to consider the silent struggles behind outward appearances and the profound impact of societal expectations on individual identity.

SCHOOLGIRL

Waking up in the morning is always interesting. It reminds me of playing hide-and-seek: I'm crouching in a dark cupboard when Deko suddenly throws open the door and sunlight pours in as she shouts, 'Found you!' That dazzling glare is followed by an awkward pause. My heart pounds as I adjust the front of my kimono and emerge from the cupboard. I feel slightly self-conscious, then suddenly irritated and annoyed. It's similar, but not quite like that — somehow it's even more unbearable. It's sort of like opening a box, only to find another box inside. You open that smaller box, and there's another box inside. You open that one too, and there are more boxes inside each other. You keep opening them — seven or eight of them — until finally what's left is a tiny box the size of a small die. You gently pry it open, but it's empty. It's more like that feeling. Anyway, it's a lie when they say your eyes just blink awake. My eyes are bleary and cloudy at first, but gradually they open as the starch settles to the bottom and the skim rises to the top. Mornings seem forced to me. So much sadness rises up; I can't bear it. I hate it; I really do. I'm an awful sight in the morning. My legs feel so exhausted that I don't want to do anything yet. I wonder if it's because I don't sleep well. They're lying when they say you feel healthy in the morning. Mornings are grey. Always the same. Absolutely empty. When I lie in bed each morning, I'm always so pessimistic. It's awful, really. All kinds of terrible regrets flood my mind at once, and I writhe in agony as my heart stops up.

Mornings are torture.

'Father,' I tried calling out softly. Feeling strangely embarrassed yet happy, I got up and hastily folded my bedding away. As I lifted it, I was startled to hear myself exclaim, 'Alley-oop!' I never thought I was the kind of girl who would utter such an unrefined expression. It's the kind of thing an old lady would shout. It's disgusting. Why did I say such a thing? It's as if there's an old lady inside me somewhere, and it makes me feel sick. I'll have to be careful from now on. I became deeply depressed, just like when I was repelled by a stranger's uncouth gait, only to realize that I was walking in exactly the same way.

I never have any confidence in the mornings.

I sat in front of the dressing mirror in my nightclothes. Without my glasses, my face looked blurry and moist when I peered at myself in the mirror. I hate my glasses more than anything else about my face, but there are certain advantages to wearing glasses that other people might not understand. I like to take them off and look out into the distance. Everything goes hazy, like a dream or a zoetrope — it's wonderful. I can't see any dirt. Only big things enter my vision: vivid, intense colors and light. I also like to take my glasses off and look at people. All of the faces around me seem kind, pretty and smiling. Furthermore, when I take my glasses off, I never think about arguing with anyone, nor do I feel the need to make snide remarks. I just blankly stare in silence. During those moments, I think that I must look like a nice young lady to everyone else. I don't worry about the gawking; I just want to bask in their attention. I feel really mellow.

But glasses are actually the worst. Any sense of your face disappears when you put them on. They obstruct whatever emotions might appear on your face: passion, grace, fury, weakness, innocence or sorrow. It's curious how impossible it becomes to communicate with your eyes.

Glasses are like a ghost.

I hate glasses so much because I think the beauty of your eyes is the best thing about people. Even if someone can't see your nose or your mouth is hidden, I think all you need are beautiful eyes that inspire others to live more beautifully when they look into them. My own eyes are just big saucers; there's nothing more to them. When I look closely at them in the mirror, I'm disappointed. Even my mother says I have unremarkable eyes. You might say that there is no light in them. They're like lumps of charcoal — they're that unfortunate. Do you see what I mean? It's dreadful. Every time I see them in the mirror, I think to myself that I wish I had nice, sparkling eyes. Eyes like a deep blue lake or eyes that reflect the vast sky you might see while lying in a lush green meadow with clouds drifting by. You might even see the shadow of birds in them. I hope I meet lots of people with lovely eyes.

'Today is May,' I reminded myself, and my mood seemed to lighten a bit. In fact, I felt happy. Soon it would be summer. As I went out into the garden, I noticed the strawberry flowers. The reality of my father's death felt strange to me. The fact that he had died — had passed away — seemed impossible to comprehend. I couldn't get my head around it. I missed my older sister and people I used to be friends with and hadn't seen in a long time. I cannot stand mornings because I am always bleakly reminded of times long gone, and of people I used to know. Their presences feel eerily close, like the scent of pickled radish that you just can't get rid of.

The two dogs, Jappy and Poo — we call him Poo because he is such a poor little thing — came running over. I made them both sit in front of me, but I only petted Jappy. Jappy's pale fur gleamed. Poo was dirty. While I was stroking Jappy, I was fully aware of Poo beside him, who looked as though he was about to start whining. I was also aware that Poo was crippled. I hate how sad Poo is. I can't stand how poor and pathetic he is, and because of that, I am cruel to him. He looks like a stray dog, so there's no telling when he might get caught and killed. With his leg like that, he would be too slow to escape. Hurry up, Poo! Go on up into the mountains! No one's going to take care of you, so you might as well die. I'm the kind of girl who will say or do unspeakable things, not just to Poo, but to anyone. I annoy and provoke people. I really am a horrid girl. As I sat on the veranda rubbing Jappy's head, I gazed at the lush green leaves and felt a pang of longing to sit directly on the ground.

I felt like trying to cry. I held my breath for a while to make my eyes bloodshot and thought I might squeeze out a tear, but it didn't work. Maybe I've turned into an impassive girl.

I gave up and started cleaning the house. As I cleaned, I found myself singing a song from the film Tojin Okichi. I felt like I ought to look around. It's amusing that I, who am usually wild about Mozart and Bach, would unconsciously break out into a song from Tojin Okichi. If I carry on saying 'Alley-oop' when I hoist the bedding or singing 'Tojin Okichi' while cleaning, there'll be no hope left for me. At this rate, I fear the crude things I might say in my sleep. Still, there was something odd about it, so I put down the broom and smiled to myself.

I changed into the underclothes that I had finished sewing yesterday. I had embroidered little white roses on the bodice. This embroidery was hidden once I had put on the rest of my clothes. No one knew it was there. How brilliant.

Mother, who was busy arranging a marriage, had gone out early that morning. She had devoted herself to other people ever since I was little, so I was used to it by now, but it really was amazing how she was constantly in motion. She impressed me. Father did nothing but study, so it fell to Mother to take up his role. Father was far removed from social interactions, but Mother knew how to surround herself with lovely people. The two of them seemed an unlikely pairing, but there was mutual respect between them. People must often have said of them, 'What a handsome, untroubled couple without any unattractive qualities.' Oh, I'm so cheeky!

While the miso soup was warming up, I sat in the doorway of the kitchen and stared idly at the copse of trees outside. I had the odd sensation that I had been sitting there like this for a very long time and would continue to do so, forever, in the same pose, thinking the same thoughts and looking at the same trees. It felt as if the past, the present and the future had all merged into one. Such things happen to me from time to time. I'd be sitting there talking to someone. My gaze would wander to a corner of the table and fix itself there, unmoving. Only my mouth would move. At times like these, I would experience a strange hallucination. I feel absolutely certain that I've had the same conversation before, under these very conditions, while staring at the corner of the table, and that it will continue indefinitely in exactly the same way. Whenever I walk along a country path, no matter how remote, I feel certain that I have been on it before. As I walk and pluck soybean leaves from the edge of the path, I think that I have surely been on this same path and plucked these same leaves before. I believe that from then on, I will repeatedly walk along this path and pull soybean leaves from the same spots. Again, these kinds of things happen to me. Sometimes, I'll be soaking in the bath and suddenly catch sight of my hand. I become convinced that, however many years from now, while I'm soaking in the bath, I'll be transported back to this moment when I randomly glanced at my hand and stared, and I'll remember how it made me feel. These thoughts always make me rather gloomy. Once, when I was putting rice into an ohitsu serving bowl, I was struck by something. It would be an exaggeration to call it inspiration, but I felt a charge running through my body. I would almost call it a philosophical insight, and I gave myself over to it. Then my head and chest became transparent, and a sense of my own existence floated down and settled over me. Silently and without making a sound, I felt at the mercy of these waves — a light and beautiful feeling that I would be able to live on like this. This wasn't a philosophical commotion, though. Rather, it was frightening — this premonition of living like a kleptomaniac cat: stealthily and quietly. It couldn't lead to anything good. If you go on like that for any length of time, you end up as if you're possessed. Like Jesus Christ. But the idea of a female Jesus Christ seems appalling.

Ultimately, though, since I'm idle most of the time and don't have any real troubles to worry about, I wonder if I'm desensitised to the hundreds, if not thousands, of things I see and hear every day. In my bewilderment, those things assail me one after another like floating ghosts.

I sat down to eat breakfast by myself in the dining room. I ate cucumbers for the first time this year. Summer seems to come from the greenness of a cucumber. The green of a May cucumber evokes a sadness akin to an empty heart: an aching, ticklish sadness. When I eat alone in the dining room, I get a wild urge to travel. I want to get on a train. I opened the newspaper. There was a photo of the actor Jushiro Konoe. I wondered if he was a nice person. I decided I didn't like the look of him. There was something about his forehead. My favorite part of the newspaper is the book advertisements. They must cost one or two hundred yen for each character on each line, so whoever writes them must try their best. Each character and phrase must generate the greatest possible impact, resulting in sentences that are wonderfully crafted and full of emotion. Such expensive words must be pretty rare in the world. There's something I like about that. It's thrilling.

I finished eating, locked up the house and headed for school. 'There's no rain,' I thought to myself, 'but I still want to walk with the nice umbrella Mother gave me yesterday, so I'll take it with me.' Mother used this parasol a long time ago, when she first got married. I felt quite proud to have found this interesting umbrella. Carrying it made me feel as though I were strolling through the streets of Paris. I thought that an antique parasol like this would come back into fashion when the war ended. It would look great with a bonnet-style hat. I'd wear a long, pink kimono with a wide, open collar and black lace gloves, with a beautiful violet tucked into the large, wide-brimmed hat. When everything was lush and green, I would go to a Parisian restaurant for lunch. Resting my cheek lightly in my hand, I would gaze wistfully at the passers-by outside. Suddenly, someone would gently tap me on the shoulder. Suddenly, the Rose Waltz would start playing. Oh, how amusing! But in reality, it was just an odd, tattered umbrella with a spindly handle. I really am miserable and pathetic. Like the Little Match Girl. I decided to do a little weeding and then leave.

On my way, I stopped to pull up some weeds in front of the house as a bit of volunteer service to Mother. Maybe something good would happen today. Even though all the weeds looked the same, some seemed to beg to be pulled, while others were quietly left behind. The likeable and unlikeable weeds looked exactly the same, yet were clearly divided into innocuous and horrible categories. It didn't stand to reason. What a girl likes and dislikes seems rather arbitrary to me. After ten minutes of volunteering to weed, I hurried to the depot. Whenever I pass the field road, I feel inspired to paint a picture. On the way, I took the path through the shrine's woods. I had discovered this shortcut all on my own. As I walked along the path, I happened to look down and saw short patches of barley growing here and there. Seeing this new green barley, I knew that the soldiers were here again this year. As in previous years, many soldiers and horses came and stayed in these woods by the shrine. Some time later, I came through here and saw the barley flourishing, just as it is today. But the barley hadn't grown any taller. Again this year, grains had spilled out of buckets intended for the soldiers' horses and taken root. Here in these dark woods, which saw hardly any sunlight, the reeds sadly wouldn't grow any taller; they would likely just wither away.

Emerging from the path through the shrine's woods, I found myself on the road close to the station with four or five labourers. As usual, they spat some nasty, unmentionable phrases in my direction. I hesitated, unsure of what to do. I wanted to pass them, but I'd have to weave my way through them to do so. That was scary. On the other hand, standing there without saying anything and waiting a while for the laborers to get far ahead of me would take much more courage. It would be rude and they might get angry. My body grew hot and I felt like I was about to cry. Feeling ashamed to be on the verge of tears, I turned and laughed in the direction of the men. Then, slowly, I started walking after them. That might have been the end of it, but even after I was on the train, I was still embarrassed. I wished I could hurry up and become stronger and purer, so that such a trivial matter would no longer bother me.