1,90 €

Mehr erfahren.

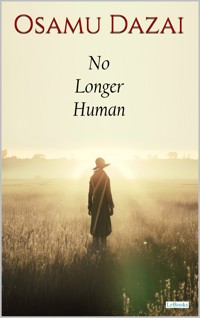

- Herausgeber: Lebooks Editora

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

No Longer Human is a deeply introspective exploration of alienation, identity, and the struggle for self-acceptance in a rapidly changing society. Osamu Dazai presents the fragmented life of Ōba Yōzō, a man unable to reconcile his outward persona with his inner despair, navigating a world where human connection feels impossible and authenticity seems unattainable. Through a series of confessional notebooks, the narrative confronts the psychological disintegration of its protagonist, revealing the corrosive effects of isolation, guilt, and societal expectations. Since its publication, No Longer Human has been recognized as one of the most significant works of modern Japanese literature, praised for its unflinching honesty and emotional depth. Its exploration of universal themes such as the fear of rejection, the search for meaning, and the destructive consequences of self-alienation has resonated with readers across cultures and generations. The novel's stark portrayal of mental anguish and existential crisis continues to speak to those grappling with the tension between their inner selves and the facades they present to the world. The enduring power of No Longer Human lies in its capacity to strip away illusions and confront the raw, uncomfortable truths about the human condition. By examining the fragile boundaries between authenticity and performance, belonging and estrangement, Dazai invites readers to reflect on the cost of disconnection — and on the profound human need for understanding, compassion, and genuine connection.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 163

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Osamu Dazai

NO LONGER HUMAN

Original Title:

“Ningen Shikkaku”

Contents

INTRODUCTION

PROLOGUE

NO LONGER HUMAN

THE FIRST NOTEBOOK

THE SECOND NOTEBOOK

THE THIRD NOTEBOOK: PART ONE

THE THIRD NOTEBOOK: PART TWO

EPILOGUE

INTRODUCTION

Osamu Dazai

1909 – 1948

Osamu Dazaiwas a Japanese novelist, widely regarded as one of the most significant literary figures of 20th-century Japan. Born in Kanagi, Aomori Prefecture, Dazai is best known for his works that explore themes of alienation, self-destruction, and the search for meaning in a rapidly modernizing society. His deeply personal and often semi-autobiographical narratives reflect the turmoil of his own life, marked by repeated suicide attempts and a profound sense of existential despair. Today, his novels No Longer Human (1948) and The Setting Sun (1947) stand as classics of modern Japanese literature.

Early Life and Education

Osamu Dazai, born Shūji Tsushima, was the eighth child of a wealthy landowning family. Despite his privileged background, he felt alienated from his family and community from an early age. His upbringing was strict, and he struggled to connect with his authoritarian father and the expectations of his class. Dazai studied French literature at the University of Tokyo but never graduated, as his life began to spiral into instability due to personal and financial troubles, substance abuse, and his growing obsession with literature. During his youth, he became heavily influenced by Western writers such as Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Anton Chekhov, and Franz Kafka, as well as by the Japanese I-novel tradition, which favored confessional, autobiographical storytelling.

Career and Contributions

Dazai’s work is characterized by its confessional style, blending fiction and autobiography to the point where the boundaries between the two become blurred. His writing often depicts disillusioned and self-destructive protagonists, mirroring his own struggles with depression and addiction. In The Setting Sun, Dazai portrays the decline of the Japanese aristocracy in the aftermath of World War II, capturing a nation in moral and social transition. No Longer Human, considered his masterpiece, is a haunting account of a man incapable of conforming to societal norms, descending into isolation and despair—a reflection of Dazai’s own inner turmoil.

His short stories, such as Run, Melos! and Schoolgirl, reveal his versatility, ranging from allegorical retellings of classical myths to sensitive portrayals of youthful innocence. Through his unique voice, Dazai merged traditional Japanese narrative elements with Western literary influences, creating a body of work that remains distinct in both tone and subject matter.

Impact and Legacy

Dazai’s work resonated deeply with postwar Japan, a society grappling with the collapse of its traditional values and the trauma of defeat. His candid exploration of human weakness, self-doubt, and alienation spoke to a generation struggling to find meaning in a changing world. His style, marked by irony, humor, and pathos, has influenced countless Japanese authors, including Yukio Mishima and Haruki Murakami.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Dazai’s appeal endures strongly among younger readers, who find in his works an intimate reflection of personal insecurity and existential struggle. Internationally, his novels have gained recognition for their universal themes, and translations have introduced his voice to readers around the world.

On June 13, 1948, Dazai and his lover Tomie Yamazaki committed double suicide by drowning in the Tamagawa Canal in Tokyo. He was only 38 years old. His tragic death cemented his image as a romantic, tormented artist, forever linked to the confessional nature of his works.

Although his career was brief, Osamu Dazai left a lasting mark on Japanese literature. His ability to confront the darkness of the human psyche with honesty and lyricism ensures his place as one of Japan’s most compelling literary voices. His novels continue to be read, studied, and adapted, maintaining their relevance as timeless meditations on the fragility of identity and the struggle to belong.

About the work

No Longer Human is a deeply introspective exploration of alienation, identity, and the struggle for self-acceptance in a rapidly changing society. Osamu Dazai presents the fragmented life of Ōba Yōzō, a man unable to reconcile his outward persona with his inner despair, navigating a world where human connection feels impossible and authenticity seems unattainable. Through a series of confessional notebooks, the narrative confronts the psychological disintegration of its protagonist, revealing the corrosive effects of isolation, guilt, and societal expectations.

Since its publication, No Longer Human has been recognized as one of the most significant works of modern Japanese literature, praised for its unflinching honesty and emotional depth. Its exploration of universal themes such as the fear of rejection, the search for meaning, and the destructive consequences of self-alienation has resonated with readers across cultures and generations. The novel’s stark portrayal of mental anguish and existential crisis continues to speak to those grappling with the tension between their inner selves and the facades they present to the world.

The enduring power of No Longer Human lies in its capacity to strip away illusions and confront the raw, uncomfortable truths about the human condition. By examining the fragile boundaries between authenticity and performance, belonging and estrangement, Dazai invites readers to reflect on the cost of disconnection — and on the profound human need for understanding, compassion, and genuine connection.

PROLOGUE:

I have seen three pictures of the man.

The first is a childhood photograph, showing him at around ten years old. He is a small boy, surrounded by a great many women (his sisters and cousins, no doubt). He is wearing brightly checked trousers and is standing by the edge of a garden pond. He has tilted his head at a thirty-degree angle to the left and bared his teeth in an ugly smirk. Ugly? You might question the choice of word, as insensitive people (i.e. those indifferent to matters of beauty and ugliness) would blandly comment, "What an adorable little boy!" It's true that this child's face has enough of what commonly passes for 'adorable' to give the compliment some meaning. However, I think that anyone with even the slightest exposure to beauty would most likely toss the photograph aside with the gesture used to brush away a caterpillar and mutter, in profound revulsion, 'What a dreadful child!'

The more carefully you examine the child’s smiling face, the more an indescribable horror will creep over you. You realise that it is not actually a smile at all. The boy does not even hint at a smile. Look at his tightly clenched fists for proof of this. No human being can smile with their fists clenched like that. It is a monkey. A grinning monkey face. The smile is nothing more than an ugly puckering of wrinkles. The photograph captures an expression that is both freakish and unclean, and even nauseating. Your impulse is to cry out, 'What a wizened, hideous little boy!' I have never seen a child with such an inexplicable expression.

The face in the second snapshot is startlingly different from the first. In this picture, he is a student, although it is unclear whether the photograph was taken during his time at high school or college. In any case, he is extraordinarily handsome now. However, once again, the face fails to give the impression of belonging to a living human being. He is wearing a student's uniform, and a white handkerchief can be seen peeping out of his breast pocket. He sits in a wicker chair with his legs crossed. He is smiling again, this time not with a wizened monkey’s grin, but with a rather adroit little smile. Yet somehow it is not the smile of a human being; it utterly lacks substance — all that we might call the 'heaviness of blood' or the 'solidity of human life'. It has not even the weight of a bird. It is merely a blank sheet of paper, light as a feather, smiling. In short, the picture produces a sensation of complete artificiality. Pretence, insincerity and fatuousness do not quite cover it. And, of course, you couldn't simply dismiss it as dandyism. In fact, if you look carefully, you will begin to sense something unpleasant about this handsome young man. I have never seen a young man whose good looks were so baffling.

The remaining photograph is the most monstrous of all. It is impossible to guess his age in this one, though his hair seems streaked with grey. It was taken in a corner of an extraordinarily dirty room – you can plainly see in the picture how the wall is crumbling in three places. His small hands are held in front of him. This time, he is not smiling. There is no expression whatsoever. The picture has a genuinely chilling, foreboding quality; it is as if he was dying while sitting in front of the camera with his hands over a heater. This is not the only shocking thing about the picture. The head is shown quite large, and you can examine the features in detail. The forehead, wrinkles, eyebrows, eyes, nose, mouth and chin are all average. The face is not merely devoid of expression; it fails to make an impression at all. It has no individuality. After looking at it, I only have to shut my eyes to forget the face. I can remember the wall of the room and the small heater, but I cannot recall anything about the face of the main figure in the room. This face could never be the subject of a painting, not even a cartoon. I open my eyes. There is no pleasure in recollection: of course, that's what the face was like! In the most extreme terms, when I open my eyes and look at the photograph again, I still cannot remember it. Besides, I find it off-putting and it makes me feel so uncomfortable that, in the end, I want to avert my eyes.

I think even a death mask would convey more expression and leave more of an impression. This effigy is reminiscent of nothing so much as a human body to which a horse’s head has been attached. There is something ineffable about it that makes the beholder shudder in distaste. I have never seen such an inscrutable face on a man.

NO LONGER HUMAN

THE FIRST NOTEBOOK

Mine has been a life of much shame.

I cannot even begin to imagine what it is like to live as a human being. I was born in a village in the north-east of the country, and it wasn’t until I was quite old that I saw my first train. I climbed up and down the station bridge, unaware that it was there to allow people to cross from one track to another. I was convinced that the bridge had been built to add an exotic touch and make the station a more diverse and pleasant place, like a foreign playground. I remained under this delusion for a long time, and climbing up and down the bridge was a very refined amusement for me indeed. I thought it was one of the most elegant services provided by the railways. However, when I later discovered that the bridge was merely a utilitarian device, I lost all interest in it.

Similarly, when I was a child and saw photographs of underground trains in books, I never thought that they had been invented out of practical necessity. I imagined that traveling underground instead of above ground must be an exciting pastime.

I have been unwell ever since I was a child and have often been confined to bed. How often, as I lay there, did I think about how uninspired the decorations on sheets and pillowcases are! It wasn't until I was about twenty that I realized they actually served a practical purpose. This revelation about human dullness plunged me into a deep depression.

I have also never known what it means to be hungry. I don't mean to suggest that I was raised in a wealthy family — I have no such intention. I mean that I have never had the slightest idea what the sensation of “hunger” is like. It sounds strange, but I have never been aware of an empty stomach. When I returned home from school as a boy, the people at home would make a great fuss over me. 'You must be hungry,' they would say. We remember how hungry you are by the time you get home from school. How about some jelly beans? There’s cake and biscuits too.” Eager to please, I would mumble that I was hungry and quickly eat a dozen jelly beans, but I had no idea what they meant by being hungry.

I do eat a great deal, of course, but I have almost no recollection of ever doing so out of hunger. It's unusual or extravagant things that tempt me. When I go to somebody else's house, I eat almost everything put before me, even if it takes some effort. When I was a child, mealtime was undoubtedly the most painful part of the day, especially at home.

At my house in the country, the whole family – about ten of us – ate together, sitting in two facing rows at the table. As the youngest, I naturally sat at the end. The dining room was dark, and the sight of ten or more family members eating lunch or dinner in gloomy silence was enough to send chills through me. Besides, this was an old-fashioned, rural household where the food was more or less prescribed, so it was useless to even hope for unusual or extravagant dishes. I dreaded mealtimes more and more each day. I would sit at the end of the dimly lit table, trembling as if I were cold, and lift a few morsels of food to my mouth, pushing them in. 'Why must human beings eat three meals every single day?' What extraordinarily solemn faces they all make as they eat! It seems to be some kind of ritual. Three times a day, at the same time, the family gathers in this gloomy room. The places are laid out in the proper order, and regardless of whether we’re hungry, we munch our food in silence with lowered eyes. Who knows? It may be an act of prayer to appease whatever spirits may be lurking around the house. At times, I went so far as to think in such terms. At times, I even thought in such terms.

Eat or die, as the saying goes, but to me it sounded like just one more unpleasant threat. Nevertheless, I could only think of this superstition as such, and it always aroused doubt and fear in me. Nothing was harder for me to understand or more baffling than the commonplace remark, 'Human beings work to earn their bread, for if they don't eat, they die.'

In other words, you might say that I still have no understanding of what makes human beings tick. When I discovered that my concept of happiness seemed completely different to everyone else's, I was so anxious that I tossed and turned and groaned in bed night after night. Indeed, it drove me to the brink of lunacy. I wonder if I have ever been happy. People have told me countless times, ever since I was a child, how lucky I am, but I have always felt as if I were suffering in hell. In fact, it has seemed to me that those who called me lucky were incomparably more fortunate than I am.

Sometimes I have thought that I have been burdened with ten misfortunes, any one of which, if borne by my neighbor, would make him a murderer.

I simply don’t understand. I have no idea what my neighbor's troubles could be like. Practical troubles and griefs that can be assuaged with enough food may be the most intense of all burning hells — horrible enough to obliterate my ten misfortunes. But that is precisely what I don’t understand. If my neighbors manage to survive without killing themselves or going mad; if they maintain an interest in political parties; if they don't yield to despair; if they resolutely pursue the fight for existence — can their griefs really be genuine? Am I wrong to think that these people have become such complete egoists, so convinced of the normality of their way of life, that they have never once doubted themselves? If so, their suffering should be easy to bear; it is the common lot of human beings, and perhaps the best one can hope for. I don’t know... I suppose if you’ve slept soundly at night, the morning is exhilarating. What kind of dreams do they have? What do they think about when they walk along the street? Money? Hardly – it can't be just that. I seem to recall hearing the theory that human beings live to eat, but never that they live to make money. And yet, in some instances... ... No, I don’t even know that. ... The more I think about it, the less I understand. All I feel is apprehension and terror at the thought that I am entirely different from everyone else. It's almost impossible for me to talk to other people. What should I talk about? How should I say it? I don't know.

This is how I came to invent my clowning.

It was the last attempt at finding love that I would make with human beings. Despite my mortal dread of human beings, I seemed unable to renounce their society. I managed to maintain a smile on my lips, which never deserted me; this was the accommodation I offered to others, a most precarious achievement that cost me excruciating effort.

As a child, I had no idea what others, even my own family, were suffering or thinking. I was only aware of my own unspeakable fears and embarrassments. Before anyone rearised it, I had become a consummate clown, a child who never uttered a truthful word.

Looking at photographs taken around that time with my family, I noticed that everyone else has serious faces, but mine is invariably contorted into a peculiar smile. This was just another one of my childish, pathetic antics.

I never once answered back to anything said to me by my family. Even the slightest reprimand would strike me with the force of a thunderbolt and drive me almost out of my mind. Answer back! On the contrary, I was convinced that their reprimands were undoubtedly voices of truth from past ages speaking to me; I was obsessed with the idea that, lacking the strength to act in accordance with this truth, I had already been disqualified from living among human beings. This belief made me incapable of arguing or justifying myself. Whenever I was criticized, I felt certain that I had been living under the most dreadful misapprehension. I always accepted the criticism in silence, though I was so terrified inwardly that I was almost out of my mind.

I suppose it's true that nobody finds it pleasant to be criticized or shouted at, but when someone is angry with me, I see a wild animal in its true colors — one more horrible than any lion, crocodile or dragon. People usually hide this true nature, but there will be an occasion when anger makes them reveal human nature in all its horror, as when an ox ensconced sedately in a grassy meadow suddenly lashes out with its tail to kill the horsefly on its flank. Seeing this has always induced in me a great fear, making my hair stand on end. At the thought that this nature might be a prerequisite for human survival, I have come close to despairing of myself.

I have always been frightened of human beings. Unable to feel any confidence in my ability to speak and act like a human being, I kept my solitary agonies locked in my heart. I kept my melancholy and agitation hidden, careful that no trace should be left exposed. I feigned innocent optimism and gradually perfected the role of the farcical eccentric.