20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

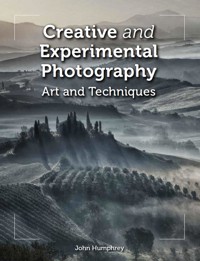

More photos are taken than ever before, but most are neglected and unused. This book suggests new creative directions and explains how you can produce distinctive and exciting works of art. Packed with technical advice and in-depth practical detail, it shows you how to use cameras and equipment for experimental photography. There are ideas on how to develop a creative eye and a personal photographic style. It explains when to use the rules of composition, and when to break them and shows you how to create amazing pictures from everyday objects. It provides inspiration, ideas and techniques for making abstract and pattern pictures, and using textures for artistic impact. Finally, it advises on using software to convert pictures to artwork and how to present art images for maximum effect. Through step-by-step guides and stunning examples, it also helps you create images that tell a personal story. It's an essential guide to help you take photos that count, not just click away.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 274

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

CreativeandExperimentalPhotography

Moscow orb. The original picture of Saint Basil’s Cathedral was distorted using Photoshop’s Polar Coordinates filter to produce a circular semi-abstract presentation. Original picture 28mm lens, ISO 100, 1/500sec, f5.6.

CreativeandExperimentalPhotography

Art and Techniques

John Humphrey

First published in 2022 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2022

© John Humphrey 2022

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 71984 000 5

Cover design: Peggy & Co. Design

CONTENTS

Introduction

1 Developing Creative Vision

2 The Rules of Composition

3 Blurring

4 Simplicity

5 Abstraction

6 Monochrome

7 Texture and Noise

8 Detail

9 New Angles on Flowers

10 Still Life and Everyday Objects

11 Equipment

12 Using Software

13 Presentation

Index

Introduction

Nowadays everyone carries a camera, and everyone takes photographs. However, these rarely embody any personal style or artistry and often stay unopened and un-viewed on the computer or mobile phone. But everyone has an artist in them, and each person’s photographs have the potential to tell a personal story and to become genuine artworks.

Fig. 0.1Cornflowers. A section of a field of wild cornflowers given a painterly treatment with Photoshop’s Oil Paint filter. 50mm lens, ISO 250, 1/250sec, f8.

Creative and Experimental Photography is a distillation of my experience and experiments in developing a distinctive photographic style. It starts by considering the nature of creativity and finding that it is not the gift of a selective few, but a tool that everyone can use. It then presents ideas and techniques by which ‘ordinary’ photographs can be the basis for new and original pictures. Photographic illustrations enable readers to see a range of styles and home in on their own personal interests and vision.

The ideas and techniques are not dependent on expensive equipment or sophisticated computer skills, although equipment options and digital manipulation are covered for those who enjoy those routes. Amazing pictures can be produced by simple adjustments, or by looking at everyday objects in new ways.

The book provides a journey for the reader. It examines the so-called rules of photography and asks whether they are a help or a hindrance to becoming a creative photographer. It then looks at ways in which simplicity can be distinctive, for example by removing colour or detail. Other techniques add impact and drama by enhancing colour and finding pattern and abstraction.

The aim is to provide all readers with inspiration, ideas and techniques to find their own inner vision and to reveal this in their photographs.

The author’s work can be viewed on his website, www.johnhumphrey.co.uk

Chapter 1

Developing Creative Vision

You have to let yourself go to be creative. Children possess this quality but then seem to lose it as they are told, ‘it’s not the done thing’.

RICKY GERVAIS

Creativity is hard to define. Some things cannot be pinned down by language. They relate to human emotion and experience. In photography, as in all pictorial art, creativity is striking and recognizable but is not necessarily open to analysis.

Fig. 1.1Drama was added to this picture of primula by adding motion blur and texture in Photoshop and increasing colour saturation.

Creativity is the process of producing something new, but not just any new thing. Creative art delivers something that stretches horizons, excites and inspires, and triggers an emotional response. In this book the definition of creative photography is:

The production of images with photographic origins, which utilize the photographer’s imagination and skill to create results that are

Different, Distinctive and Personal

Different means that a creative photograph is not a copy of an existing photograph or of someone else’s artwork. It must be genuinely something new.

Fig. 1.2This picture of rooftops in Bruges was converted to a more personal representation by superimposing a section of the roofs over a blue-toned image of the building windows.

It would of course be easy to produce something different that was devoid of any merit. So the second condition, Distinctive, must also apply. This requires a level of quality so that the picture delivers a strong emotional and artistic message.

Finally, the image should be a Personal statement by the photographer. It should communicate the author’s vision of the world and tell an individual story. The photographer knows they have succeeded in developing a personal style when someone looks at a picture and knows that it is one of theirs.

FOR A CHOSEN FEW?

When admiring the work of great photographers, artists and designers, it is easy to feel rather defeated and to think that those heights are beyond the aspiration of ordinary mortals. Fortunately, this is wrong! The many studies and papers on the subject demonstrate that creativity is within the grasp of everyone. However, it seems that creativity is not something to learn as though it was a new skill, but that it is something to retrieve from earlier years. The researcher Dr George Land gave the NASA creativity test to five-year-old children and found that they delivered an average creativity score of 98 per cent. By the age of ten this had dropped to 30 per cent, and by the age of fifteen to 12 per cent. By adulthood, the average score was 2 per cent. People had unlearned creativity.

During development, humans acquire language, systems and rules. These deliver coping skills, but at the expense of creativity. This chapter explores ways to shake off the habits of adulthood and find ways to see the world through different eyes, the eyes of young children.

THE NASA CREATIVITY TEST

Age

Average Score

Five

98%

Ten

30%

Fifteen

12%

Adult

2%

DR GEORGE LAND

LEAVE THE COMFORT ZONE

Children are reckless explorers, uninhibited and unaware of danger. With experience they become conscious of risk and find patterns of behaviour that work in a challenging world. These become ingrained and rooted in habits. Any deviation triggers the stress response, often called ‘fight or flight’ since change is instinctively perceived as dangerous. As a result, people tend not to experiment with new ways of doing things and can resist new experiences. This is generally completely unconscious. Even an active desire for novelty and excitement finds itself limited by social, parental and procedural limitations.

Fig. 1.3A picture taken through a car windscreen on a rainy day produces an unusual abstract. The camera was focused on the windscreen surface so that the distant objects become unrecognizable and only contribute colour and shape. 50mm lens, ISO 500, 1/30sec, f4.

Reawakening creative vision requires looking out of the box and resisting the inner voices saying this is not the way to do things. At first this might be uncomfortable, even painful, but it will be worth it for the new avenues – the new photographs – that will emerge.

TRY SOMETHING NEW

A good starting point to reawakening personal creativity is to do something completely new. In photography this could be to find new subjects, use different equipment or try new processing techniques. Remember that the aim is to experience some discomfort in doing this, not to just nudge the boundaries a little. So here are some suggestions – it is best to pick one that looks unfamiliar and challenging:

Fig. 1.4A picture of London at night during heavy rain showing colourful pavement reflections. It is difficult to hold a camera and an umbrella at the same time, but the results can be worthwhile. 50mm lens, ISO 1000, 1/60sec, f5.6.

•Take a photograph in pouring rain

•Photograph the contents of the cutlery drawer

•Take a self-portrait

•Take a picture through frosted glass

•Photograph a dead flower

•Find an entirely abstract composition

•Produce a picture that illustrates a favourite piece of music

Bear in mind that the aim at this stage is not so much to produce a great picture, as to open new circuits in the brain and to become receptive to more creative artistic directions.

Fig. 1.5A surprising range of pictures can be produced from objects close to hand. In this case, three forks resting on a mirror and the image converted to black and white. 100mm lens, ISO 100, 1/15sec, f4.5.

Coming up with new ideas for photography will test imagination, but no more than that. To be creative they must be put into practice.

IT’S NOT PHOTOGRAPHY!

As we push in new directions it is common to encounter negativity, often expressed with the declaration ‘it’s not photography’. This might come from outside, perhaps a camera club diehard, or a voice inside the head trying to talk us back into familiar territory. Ignore this, it doesn’t matter. This is a classic demonstration of the comfort zone in action, using a semantic argument to stifle experiment. Let others worry about the definition of photography and focus on producing pictures.

OULIPO

In 1969 the French author George Perec wrote a book titled La Disparition. This was translated into English by Gilbert Adair under the title A Void in 1994. A Void reads as an engaging thriller but with an unusual distinctive style. The reason for the unique quality of the book is that it is written entirely without the letter ‘e’. Perec went on to write a further book, translated with the title The Exeter Text: Jewels, Secrets, Sex, in which the only vowel is ‘e’.

These unusual books are examples of the Oulipo movement. Oulipo seeks to produce creative works of art by introducing a deliberate constraint on the work. The Oulipo group devised a series of techniques and exercises which set limits, forcing the artist to new levels of creativity by making them think ‘outside the box’.

Fig. 1.6This picture of woodland trees was taken through a Vaseline-smeared filter, producing a soft directional effect. 50mm lens, ISO 200, 1/40sec, f4.

Fig. 1.7A double exposure of Euston station in rush hour adds to the impression of crowds and busyness. 28mm lens, ISO 800, 1/60sec, f5.6.

Fig. 1.8Moving subjects can be effective for multiple exposure photography. The camera was set to take four pictures in quick succession for this image of a ballet dancer. 100mm lens, ISO 400, 1/30sec, f4.

Although Oulipo is primarily a literary movement, it is possible to take the same approach in photography. By restricting some aspect of the photography process, it becomes necessary to see things in new ways. At first, an Oulipo exercise will feel even more challenging than that of photographing something new. With Oulipo, it is fine to photograph familiar objects or scenes, but the agreed constraint must always be applied. After the initial frustration, and the temptation to ignore the constraint (not allowed), new and genuinely creative pictures will emerge. The photographer finds compositions that would never otherwise have come to mind.

Restriction is a gift to the creative.

GRAYSON PERRY

Here are some possible Oulipo constraints to start with. This is not a definitive list but should give an idea of the approach to take:

•Set a fixed extreme focal length on the camera and spend a day taking pictures with only that setting.

•Set a very slow shutter speed, too slow for hand stabilization, and take pictures that capture movement of the subject or the camera.

•Take all pictures through a Vaseline-smeared filter over the camera lens.

•Take all pictures as double or triple exposures (assuming this is an option in the camera settings).

•Zoom the lens during the exposure.

•Take all pictures without looking at the screen or through the viewfinder.

STAND AND STARE

Taking a photograph doesn’t feel like a process of habit, but it is. Looking around a place for good compositions, reviewing a flower for its best angles, setting up the lights for a portrait, all feel unconstrained. In reality though, habit is in control. The pictures that have worked in the past, and the familiar camera settings, are likely to dominate without the photographer having any real awareness that these factors are constraining creativity.

The exercises above, to take something new and to try an Oulipo constraint, will all help in escaping the habit trap. Another, perhaps gentler, approach is to take much more time. To contemplate a subject, to sit and stare at it, long before taking its picture.

Most photographers take a photograph, perhaps of a scenic landscape, almost before they have looked at it. This is especially noticeable with tourists who can appear to be more interested in photographing a famous site, in bagging the trophy, than they are in looking at it and appreciating it. Sometimes this is inevitable if time constraints and the pressures from other people are adding urgency. However, new and creative images will emerge if the temptation to take immediate pictures is resisted and the scene or subject is contemplated to absorb its true nature.

What is this life if, full of care,We have no time to stand and stare.

W.H. DAVIES

Here is the proposal. Choose a subject, perhaps a building or landmark that is reasonably familiar. Put away the camera and the phone, and then spend time merely looking around. Home in on detail, pattern, texture, shadows, colour. Look from new angles and observe interesting shapes. This could well take an hour or so. Then start to think photographically, though still without the camera. Mentally devise compositions that look as though they might make pictures. Then the camera is allowed! Be selective, do not take pictures for the sake of it but aim to record the observations made during the contemplative exercise.

Fig. 1.9Quiet, reflective pictures, here a seascape, can result from a focus on simple shapes and colours. 28mm lens, ISO 100, 1/800sec, f4.

The review of the resulting pictures should be equally leisurely and open-minded. Do they capture the observation and the idea intended? Do they have scope for post-production treatments of the sort described in the coming chapters? If they do not, and they may well not, why don’t they? Then comes the hard bit, going back and doing it all again to refine the process and to get the perfect picture. It takes effort, energy and determination to revisit and repeat, but the results pay dividends.

THE STATE OF FLOW

The Hungarian professor of psychology, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, noted that people have the most fulfilling experiences when they are immersed in tasks that they find interesting, pleasurable and absorbing. He called this the state of flow. According to Csikszentmihalyi, the state of flow can even bring about feelings of ‘rapture’ and ‘joy’. It is like a kind of meditation. All other thoughts are pushed out by complete absorption in the task at hand. In flow there is no sense of time or place and hours can pass by in what seems like minutes.

Fig. 1.10The state of flow results from intense focus on a demanding task. This artist is immersed entirely in the production of an intricate ink drawing. 50mm lens, ISO 800, 1/20sec, f5.

This is a state of mindfulness and, although recorded by Csikszentmihalyi in 1975, it has been observed in other cultures, particularly some Eastern religions, and sometimes has other terminology such as being ‘in the zone’.

So, what does it take to achieve a state of flow? There are three main requirements:

1.The individual must have sufficient skill to carry out the task.

2.The task needs to be challenging.

3.The motivation should be the intrinsic worth of the activity, not its financial gain or the approval of others.

If an activity is too easy, it will result in boredom. If it is not challenging, it will be tedious. If the focus is on money or approval, the creative challenge will take second place.

Creative photography presents the perfect opportunities to deliver flow. It challenges the photographer to find new ways of seeing. It demands all the photographer’s skill developed in mastering observation, technology and software. Whether the immersion comes from studying a subject to find its photographic image, developing the picture in the darkroom or in software, or producing the perfect print, the resulting state of mind will be flow.

The best moments in our lives are not the passive, receptive, relaxing times. The best moments usually occur if a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile.

MIHALY CSIKSZENTMIHALYI

FINDING IDEAS

Photographers often experience the equivalent of writers’ block. No new ideas come to mind, all possible subjects seem to have been photographed, every Photoshop technique has been tried.

This experience is a state of mind rather than a reality, there are sure to be new creative photographs out there. Nevertheless, it can help to have a few idea triggers to get back on track. Here are three approaches:

1. Plagiarize!

This might seem like an outrageous suggestion, having defined creativity as the process of producing something new and personal. Surely copying someone else’s work is the antithesis of this. However, in practice the work of others will often provoke original ideas. The aim is not to make an exact duplication, although that might be a starting point, but to build on some aspect of another image to take the photographer in a new direction.

Time in an art gallery can be well spent. While the sheer number of pictures can be overwhelming, there are likely to be one or two with particular emotional appeal. Ask what it is about them that is special. It might be a colour, a shape, a subject, simplicity or complexity. This then is the basis for a more personal project building on those characteristics.

The source of ideas does not have to be as weighty as an art gallery. Inspiration can come from designs, magazines, advertisements, and of course the photographs of others.

2. Visit the archive

This book offers a range of approaches designed to help make photographs more creative and personal. However, it is possible that it is unnecessary to take more photographs to make new pictures. Photographers are often reluctant to delete images. They are tucked away on a hard drive somewhere in the hope that one day they will come in useful. Well, now they will.

It is surprising how revealing and productive it can be to browse through long-neglected photography files. Revisited with fresh eyes they can turn out to have a new life. It is often helpful to have a specific project in mind during this image trawl. For instance, if the aim is to produce abstract pictures then photographs that were previously rejected could well have detail that delivers exactly what is needed.

Fig. 1.11Ideas for new and creative photographs can often be triggered by the work of others, in this case the Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy. 28mm lens, ISO 800, 1/200sec, f8.

Fig. 1.12Creative pictures do not necessarily require high resolution photographic images. This picture of an eye is only about 35 pixels wide but the low resolution adds intrigue and pattern.

Fig. 1.13Many relatively mundane photographs are unimpressive individually but can have impact and interest when presented as collections. In this case a set of forty-eight doors.

Sometimes the concern with photographs taken some time ago is that they might not have the quality or resolution needed for current standards. But, wearing a creative hat, this might be turned to advantage. As the coming chapters will show, many creative applications benefit from low resolution images.

3. Create a set

A collection of pictures can often make more impact, and be more intriguing, than just a single image. A set of landscapes with a horizon that is level across the series, or a sequence, perhaps of a flower unfolding, have real appeal and demonstrate attention to the subject.

The next chapter looks at the so-called rules of composition, the fifth of which is the rule of ‘odds’. This suggests that odd numbers of items in a picture are more appealing than even numbers. The same is true of sets of pictures. The classical set is the triptych, a set of three, but fives and nines (perhaps as a 3 × 3 grid) are also effective.

Fig. 1.14The statue of John Betjeman at St Pancras station offers an interesting triptych by taking three pictures from different angles. 50mm lens, ISO 800, 1/60sec, f8.

Fig. 1.15Stormy weather often provides ideal conditions for creative pictures. This London skyline across the Thames offered an atmospheric dark sky, and a diffusion texture in Photoshop added an artistic effect. 50mm lens, ISO 100, 1/500sec, f4.

Sets of pictures are especially effective for special-interest subjects. So for people interested in cars, bees, shells, spice jars, mountains or whatever, they will be drawn to a collection of those things. For those without such an interest, the pictorial impact of the set will still have impact.

DEVELOPING CREATIVE VISION – KEY POINTS

•Creative photography is the art of producing something new that is different, distinctive and personal.

•Creativity is within the gift of all photographers, but they have to unlearn some of the restrictions imposed by adulthood.

•Taking a creative photograph is likely to require departure from the comfort zone of familiarity and habit.

•Working with a deliberately applied constraint demands new ways of seeing and results in new, creative photographs.

•Creative focus leads to the condition of ‘flow’, in which there is no sense of time or place.

•New ideas can come from anywhere, including inspiration from the work of others.

Chapter 2

The Rules of Composition

Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.

PABLO PICASSO

The technical aspects of photography sometimes deflect attention from aesthetic considerations. However, success in photography is dependent on the picture being a pleasure to look at. This chapter reviews the elements of an image that affect the way it is experienced.

Fig. 2.1A composite picture from a mosque in Kuala Lumpur in which the archways have been copied several times to produce a continuous corridor, artificial rays of sunlight added, and a central figure introduced as the focal point.

Composition is a broad term describing the way the components of a picture are arranged and balanced. This includes their position within the picture frame, as well as their colour, sharpness and contrast.

Ultimately, composition is subjective. Judgement on what makes a pleasing picture varies from person to person, and culture to culture. However, there is sufficient common ground to identify basic guidelines that are useful in most circumstances. That is not to say they should never be ignored – sometimes the most successful and creative pictures are those that flaunt convention.

There are of course no real ‘rules’ of composition. No statute governs the way pictures should look and you can compose a picture absolutely any way you choose. Nevertheless, human perception of visual art does seem to be drawn towards certain consistent characteristics, which are extremely helpful in analysing images. All photographers know that it is very difficult to objectively judge one’s own work, so anything that provides a structured basis for assessment is a valuable starting point.

Here are ten criteria that have proved to be consistently helpful in assessing the aesthetic merits of a picture:

1.Place subjects and lines on thirds.

2.Introduce movement into the image.

3.Use leading diagonals and curves.

4.Look for natural frames.

5.Use odd numbers of objects.

6.Beware of distractions, especially at edges and corners.

7.Keep horizons horizontal and verticals vertical.

8.Include a full range of tones, from black to white.

9.Avoid blocks of black shadow or white highlights.

10.Ensure the subject is interesting.

NOT EVERYONE AGREES

The great photographer Edward Weston said:

Consulting the rules of composition before taking a photograph is like consulting the laws of gravity before going for a walk.

In practice, natural photographers have a ‘feel’ for composition and rarely need to think about the rules. Equally, some photographers succeed by deliberately breaking the conventions of composition.

1. THE RULE OF THIRDS

The rule of thirds is the best known of the composition guidelines. It suggests that the key features and lines in a photograph should align with a ‘noughts and crosses’ grid that separates the picture into thirds horizontally and vertically. This is so widely accepted that cameras and software often provide the facility to superimpose the grid of thirds on the image to aid composition.

Fig. 2.2This picture of monks in Sri Lanka had more interest when the main figures were off-centre and the strong lines in the image placed on the thirds. 60mm lens, ISO 100, 1/1000sec, f5.6.

When subjects, or lines such as the horizon, are placed on a third, the picture tends to have more energy and interest than if they were placed centrally. Despite this generally reliable guidance, some photographs present little option but to place the subject centrally: for example, the centre of a flower displaying radial symmetry or a slice through a circular fruit. Some subjects are simply unavoidably central.

Fig. 2.3Some subjects, such as this white dahlia, are naturally central and are not suited to an off-centre composition. 100mm lens, ISO 100, 1/30sec, f8.

An alternative positional guideline is based on the so called ‘golden section’. This is rather more complicated and is a division where the ratio of the shorter to the longer length is the same as the ratio of the longer length to the two lengths added together. This ratio is about 1:1.6. In practice, this would mean moving the subject a little more to the centre than placing on the third. The golden section was much valued in classical art and architecture. However, its application was more to set the ratio of the width of a picture to its height (the aspect ratio), than to position objects in the frame.

2. MOVEMENT INTO THE IMAGE

Many pictures have a sense of movement about them. This could be actual movement, for example of a bee flying into a flower, or just the direction in which the subject is facing. Pictures tend to look more comfortable if that direction is heading into, rather than out of, the image.

Fig. 2.4This picture of a dog on a beach was softened in Photoshop and noise added to create an artistic impression. The dog’s direction is into the image with movement from left to right. 100mm lens, ISO 200, 1/400sec, f8.

Using movement as part of composition is largely a matter of managing the space in the image. In other words, there should be more space in front of the subject than there is behind it. In an ideal world, this would be accomplished when taking the picture. However, many pictures, especially of moving subjects, involve seizing the moment and may not be perfectly composed. It is then up to the postproduction stages in software to achieve the best possible composition. If there is sufficient space in front of the main subject, then simple straightening and cropping should be enough. If there is not quite the space needed for perfect composition, then it might be possible to stretch part of the image to give the balance required. Of course, the picture is then no longer a strictly accurate representation of the scene.

The preferred direction of movement in an image depends on the direction of reading in that culture. In most Western societies where language is written from left to right, that is the aesthetic preference for the direction of movement in an image. Where language is written from right to left, as in China and Arab countries, the preference is for image movement in that direction.

3. DIAGONALS AND CURVES

Viewers enjoy a journey through a photograph, and it helps if lines and curves create a natural route for the eye to follow. Following the left to right preference, the ideal line would be a gentle diagonal curve heading upwards from bottom left. A classic study would be a flower stem leading from bottom left to the main subject of the flower itself.

Lines themselves can be the actual photograph, and this will often be the case when detail is picked out in a close-up image. Examples are cobwebs, the detail on shells and rocks, and the tines of forks. Generally, these lines are more appealing as diagonals than when parallel to the picture edge.

Fig. 2.5The tarda tulip stem provides a curved entrance to the flower, leading from bottom left. The flower has been converted to black and white with a little colour repainted into the centre. 100mm lens, ISO 100, 1/6sec, f22.

Fig. 2.6A spiral staircase provides a natural journey to the centre of the picture. The image has been sepia toned together with the addition of a light edge vignette and digital noise. To give a left to right direction the picture has been flipped horizontally. This is not strictly accurate since it is not actually the direction of most staircases. 24mm lens, ISO 250, 1/30sec, f4.

Like lines, curves can also be the subject of an image, with spirals being particularly pleasing. Photographers are always drawn to a spiral staircase! Many natural objects have a spiral structure, such as shells, ferns and cacti. Equally, the curving line might be the path that leads the eye to the main subject of the picture. Classical artists prized the golden spiral for this purpose. This is a spiral constructed by drawing quarter circles through a linked set of squares set within a golden section rectangle (aspect ratio 1:1.6). Some software enables the golden spiral to be superimposed on an image during editing, but whether the effort of aligning picture elements precisely along a golden spiral is worthwhile, is questionable.

4. NATURAL FRAMES

Images are pleasing when they are contained within some sort of frame. This concentrates attention on the image and adds impact. In everyday photography this is often arranged by taking photographs through archways or bordered by trees.

Fig. 2.7The overhanging trees provide a natural frame for the walkers with their dog. 50mm lens, ISO 800, 1/30sec, f4.

Fig. 2.8A ragged frame has been added in software to contain this picture of a bee on a scabious flower. 100mm lens, ISO 400, 1/125sec, f14.

Sometimes frames appear naturally, with flowers providing the most common opportunity. Indeed, part of the appeal of flowers is that they contain a central focal point bordered by a frame of petals. However, imaginative composition is often required to place a natural frame around other subjects.

When the subject presents no opportunity for natural framing, it can be well worthwhile to produce a frame in software. This can be an edge or border, but can also be a less obvious darkening, or vignetting, of the picture edges. Introduced carefully, this is not intrusive but enables the eye to concentrate more easily on the main subject.

5. ODD NUMBERS

The ‘rule of odds’ is based on the proposition that pictures of more than one object seem to have more balance when they contain odd rather than even numbers of the object. This is possibly because there is then a central item that balances the others. However, it gives a more comfortable image even when the items are not in a line but scattered over the frame. It has been suggested that this is because human perception tends to visually pair objects when possible and when this is blocked because there is an odd number, the image becomes easier to view.

Natural subjects do not always conveniently gather themselves into odd-numbered groups, but when it is possible to take control of the subject, the odd number rule is worth keeping in mind. In practice, this is only really important for small numbers of objects, perhaps three, five or seven, rather than two, four or six. Beyond seven, there is no immediate perception of the number.

Fig. 2.9This composite of tulip flowers is a satisfying composition with five elements but does not work with four or six. The background of the picture has been colour graded to mirror the colour gradation of the flowers. 100mm lens, ISO 100, 1/2sec, f16.

Before becoming too obsessed with the rule of odds, it is worth noting that some things come naturally in pairs and that is fine. A wedding photographer is unlikely to refuse to take a wedding photo of a bride and groom on the grounds that there are just two of them.