9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

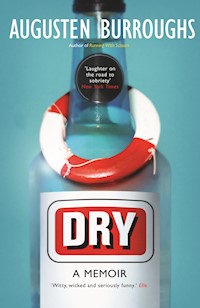

From the #1 New York Times bestselling author of Running with Scissors comes Augusten Burroughs's most provocative memoir. Outrageously fuinny and scorchingly honest. You may not know it, but you've met Augusten Burroughs. You've seen him on the street, in bars, on the underground, at restaurants: a twenty-something guy, nice suit, works in advertising. Regular. Ordinary. But when the ordinary person had two drinks, Augusten had twelve; when the ordinary person went home at midnight, Augusten never went home at all. At the request (well, it wasn't really a request) of his employers, Augusten lands in rehab, where his dreams of group therapy with Robert Downey Jr are dashed by the grim reality of fluorescent lighting and paper hospital slippers. But when Augusten is forced to examine himself, that's when he finds himself in the worst trouble of all. Because when his thirty days are up, he has to return to his same drunken life - and live it sober.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

DRY

DRY

A MEMOIR

AUGUSTEN BURROUGHS

First published in 2003 in the United States of America by St. Martin’s Press, New York.

First published in Great Britain in 2004 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

Copyright © Augusten Burroughs 2003

The moral right of Augusten Burroughs to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Author’s note: The names and other identifying characteristics of the persons included in this memoir have been changed.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback edition 1 84354 184 X Trade paperback edition 1 84354 299 4 eBook ISBN: 978 0 85789 517 2

Printed in Great Britain by Creative Print & Design, Ebbw Vale, Wales

Atlantic Books An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Part I

1. Just do It

2. Those Fucking Eggs

3. Nothing to be Proud of

4. Alcoholism For Beginners

Part II

5. Prepare for Landing

6. The British Invasion

7. The Dangers of Cheez whiz and Pimento

8. Crack(S)

9. What’ll It Be?

10. The Mirrors of La

11. Running Underwater

12. The Butterfly Effect

13. The Deep End

14. Dry

15. One Year Later

Acknowledgments

In memory of George Stathakis

For my brother

And for Dennis

PART I

JUST DO IT

Sometimes when you work in advertising you’ll get a product that’s really garbage and you have to make it seem fantastic, something that is essential to the continued quality of life. Like once, I had to do an ad for hair conditioner. The strategy was: Adds softness you can feel, body you can see. But the thing is, this was a lousy product. It made your hair sticky and in focus groups, women hated it. Also, it reeked. It made your hair smell like a combination of bubble gum and Lysol. But somehow, I had to make people feel that it was the best hair conditioner ever created. I had to give it an image that was both beautiful and sexy. Approachable and yet aspirational.

Advertising makes everything seem better than it actually is. And that’s why it’s such a perfect career for me. It’s an industry based on giving people false expectations. Few people know how to do that as well as I do, because I’ve been applying those basic advertising principles to my life for years.

When I was thirteen, my crazy mother gave me away to her lunatic psychiatrist, who adopted me. I then lived a life of squalor, pedophiles, no school and free pills. When I finally escaped, I presented myself to advertising agencies as a self-educated, slightly eccentric youth, filled with passion, bursting with ideas. I left out the fact that I didn’t know how to spell or that I had been giving blowjobs since I was thirteen.

Not many people get into advertising when they’re nineteen, with no education beyond elementary school and no connections. Not just anybody can walk in off the street and become a copywriter and get to sit around the glossy black table saying things like, “Maybe we can get Molly Ringwald to do the voice-over,” and “It’ll be really hip and MTV-ish.” But when I was nineteen, that’s exactly what I wanted. And exactly what I got, which made me feel that I could control the world with my mind.

I could not believe that I had landed a job as a junior copywriter on the National Potato Board account at the age of nineteen. For seventeen thousand dollars a year, which was an astonishing fortune compared to the nine thousand I had made two years before as a waiter at a Ground Round.

That’s the great thing about advertising. Ad people don’t care where you came from, who your parents were. It doesn’t matter. You could have a crawl space under your kitchen floor filled with little girls’ bones and as long as you can dream up a better Chuck Wagon commercial, you’re in.

And now I’m twenty-four years old, and I try not to think about my past. It seems important to think only of my job and my future. Especially since advertising dictates that you’re only as good as your last ad. This theme of forward momentum runs through many ad campaigns.

A body in motion tends to stay in motion. (Reebok, Chiat/Day.)

Just do it. (Nike, Weiden and Kennedy.)

Damn it, something isn’t right. (Me, to my bathroom mirror at four-thirty in the morning, when I’m really, really plastered.)

• • •

It’s Tuesday evening and I’m home. I’ve been home for twenty minutes and am going through the mail. When I open a bill, it freaks me out. For some reason, I have trouble writing checks. I postpone this act until the last possible moment, usually once my account has gone into collection. It’s not that I can’t afford the bills—I can—it’s that I panic when faced with responsibility. I am not used to rules and structure and so I have a hard time keeping the phone connected and the electricity turned on. I place all my bills in a box, which I keep next to the stove. Personal letters and cards get slipped into the space between the computer on my desk and the printer.

My phone rings. I let the machine pick up.

“Hey, it’s Jim . . . just wanted to know if you wanna go out for a quick drink. Gimme a call, but try and get back—”

As I pick up the machine screeches like a strangled cat. “Yes, definitely,” I tell him. “My blood alcohol level is dangerously low.”

“Cedar Tavern at nine,” he says.

Cedar Tavern is on University and Twelfth and I’m on Tenth and Third, just a few blocks away. Jim’s over on Twelfth and Second. So it’s a fulcrum between us. That’s one reason I like it. The other reason is because their martinis are enormous; great bowls of vodka soup. “See you there,” I say and hang up.

Jim is great. He’s an undertaker. Actually, I suppose he’s technically not an undertaker anymore. He’s graduated to coffin salesman, or as he puts it, “pre-arrangements.” The funeral business is rife with euphemisms. In the funeral business, nobody actually “dies.” They simply “move on,” as if traveling to a different time zone.

He wears vintage Hawaiian shirts, even in winter. Looking at him, you’d think he was just a normal, blue-collar Italian guy. Like maybe he’s a cop or owns a pizza place. But he’s an undertaker, through and through. Last year for my birthday, he gave me two bottles. One was filled with pretty pink lotion, the other with an amber fluid. Permaglow and Restorative: embalming fluids. This is the sort of conversation piece you simply can’t find at Pottery Barn. I’m not so shallow as to pick my friends based on what they do for a living, but in this case I have to say it was a major selling point.

A few hours later, I walk into Cedar Tavern and feel immediately at ease. There’s a huge old bar to my right, carved by hand a century ago from several ancient oak trees. It’s like this great big middle finger aimed at nature conservationists. Behind the bar, the wall is paneled in this same wood, inlaid with tall etched mirrors. Next to the mirrors are dull brass light fixtures with stained-glass shades. No bulb in the place is above twenty-five watts. In the rear, there are nice tall wooden booths and oil paintings of English bird dogs and anonymous grandfathers posed in burgundy leather wing chairs. They serve a kind of food here: chicken-fried steak, fish and chips, cheeseburgers and a very lame salad that features iceberg lettuce and croutons from a box. I could live here. As if I didn’t already.

Even though I’m five minutes early, Jim’s sitting at the bar and already halfway through a martini.

“What a fucking lush,” I say. “How long have you been here?”

“I was thirsty. About a minute.”

He appears to be eyeing a woman who is sitting alone at a table near the jukebox. She wears khaki slacks, a pink-and-white striped oxford cloth shirt and white Reeboks. I instantly peg her as an off-duty nurse. “She’s not your type,” I say.

He gives me this how-the-hell-do-you-know look. “And why not?”

“Look at what she’s drinking. Coffee.”

He grimaces, looks away from her and takes another sip of his drink.

“Look, I can’t stay out late tonight because I have to be at the Met tomorrow morning at nine.”

“The Met?” he asks incredulously. “Why the Met?”

I roll my eyes, wag my finger in the air to get the bartender’s attention. “My client Fabergé is creating a new perfume and they want the ad agency to join them tomorrow morning and see the Fabergé egg exhibit as inspiration.” I order a Ketel One martini, straight up with an olive. They use the tiny green olives here; I like that. I despise the big fat olives. They take up too much space in the glass.

“So I have to be there in a suit and look at those fucking eggs all morning. Then we’re all going to get together the day after tomorrow at the agency and have a horrific meeting with their senior management. Some global vision thing. One of those awful meetings you dread for weeks in advance.” I take the first sip of my martini. It feels exactly right, like part of my own physiology. “God, I hate my job.”

“You should get a real job,” Jim tells me. “This advertising stuff is putrid. You spend your days waltzing around the Met looking at Fabergé eggs. You make wads of cash and all you do is complain. Jesus, and you’re not even twenty-five yet.” He sticks his thumb and index finger in the glass and pinches the olive, which he then pops in his mouth.

I watch him do this and can’t help but think, The places those fingers have been.

“Why don’t you try selling a seventy-eight-year-old widow in the Bronx her own coffin?”

We’ve had this conversation before, many times. The undertaker feels superior to me, and actually is. He is society’s Janitor in a Drum. He provides a service. I, on the other hand, try to trick and manipulate people into parting with their money, a disservice.

“Yeah, yeah, order us another round. I gotta take a leak.” I walk off to the men’s room, leaving him at the bar.

We have four more drinks at Cedar Tavern. Maybe five. Just enough so that I feel loose and comfortable in my own skin, like a gymnast. Jim suggests we hit another bar. I check my watch: almost ten-thirty. I should head home now and go to sleep so I’m fresh in the morning. But then I think, Okay, what’s the latest I can get to sleep and still be okay? If I have to be there at nine, I should be up by seven-thirty, so that means I should get to bed no later than—I begin to count on my fingers because I cannot do math, let alone in my head—twelve-thirty. “Where you wanna go?” I ask him.

“I don’t know, let’s just walk.”

I say, “Okay,” and we head outside. As soon as I step into the fresh air, something in my brain oxidizes and I feel just the slightest bit tipsy. Not drunk, not even close. Though I certainly wouldn’t attempt to operate a cotton gin.

We end up walking down the street for two blocks and heading into this place on the corner that sometimes plays live jazz. Jim’s telling me that the absolute worst thing you can encounter as an undertaker is “a jumper.”

“Two Ketel One martinis, straight up with olives,” I tell the bartender and then turn to Jim. “What’s so bad about jumpers? What?” I love this man.

“Because when you move their limbs, the bones are all broken and they slide around loose inside the skin and they make this sort of . . .” Our drinks arrive. He takes a sip and continues, “. . . this sort of rumbling sound.”

“That’s so fucking horrifying,” I say, delighted. “What else?”

He takes another sip, creases his forehead in thought. “Okay, I know—you’ll love this. If it’s a guy, we tie a string around the end of his dick so that it won’t leak piss.”

“Jesus,” I say. We both take a sip from our drinks. I notice that my sip is more of a gulp and I will need another drink soon. The martinis here are shamefully meager. “Okay, give me more horrible,” I tell him.

He tells me how once he had a female body with a decapitated head and the family insisted on an open casket service. “Can you imagine?” So he broke a broomstick in half and jammed it down through the neck and into the meat of the torso. Then he stuck the head on the other end of the stick and kind of pushed.

“Wow,” I say. He’s done things that only people on death row have done.

He smiles with what I think might be pride. “I put her in a white cashmere turtleneck and she actually ended up looking pretty good.” He winks at me and plucks the olive from my drink. I do not take another sip from this particular glass.

We have maybe five more drinks before I check my watch again. Now it’s a quarter of one. And I really need to go, I’ll already be a mess as it is. But that’s not what happens. What happens is, Jim orders us a nightcap.

“Just one shot of Cuervo . . . for luck.”

The very last thing I remember is standing on a stage at a karaoke bar somewhere in the West Village. The spotlights are shining in my face and I’m trying to read the video monitor in front of me, which is scrolling the words to the theme from The Brady Bunch. I see double unless I close one eye, but when I do this I lose my balance and stagger. Jim’s laughing like a madman in the front row, pounding the table with his hands.

The floor trips me and I fall. The bartender walks from behind the bar and escorts me offstage. His arm feels good around my shoulders and I want to give him a friendly nuzzle or perhaps a kiss on the mouth. Fortunately, I don’t do this.

Outside the bar, I look at my watch and slur, “This can’t be right.” I lean against Jim’s shoulder so I don’t fall over on the tricky sidewalk.

“What?” he says, grinning. He has a thin plastic drink straw behind each ear. The straws are red, the ends chewed.

I raise my arm up so my watch is almost pressed against his nose. “Look,” I say.

He pushes my arm back so he can read the dial. “Yikes! How’d that happen? You sure it’s right?”

The watch reads 4:15 A.M. Impossible. I wonder aloud why it is displaying the time in Europe instead of Manhattan.

THOSE FUCKING EGGS

I arrive at the Metropolitan Museum of Art at a quarter before nine. Fifteen minutes early. I’m wearing a charcoal gray Armani suit and oxblood red Gucci loafers. My head throbs dully behind my eyes, but this has actually become normal. It usually wears off by the end of the day and is completely gone after the first drink of the evening.

I didn’t technically sleep last night, I napped. Even in my drunken stupor of last night, I realized I couldn’t show up here this morning looking like a total disaster, so I managed to call 1-800-4-WAKE-UP (You snooze, you lose!) before I laid down on my bed, fully dressed.

I was awake by six A.M. and still felt drunk. I was making wisecracks to myself in the bathroom, pulling faces. This is when I knew I was still drunk. I just had way too much energy for six A.M. Too much motivation. It was like the drunk side of my brain was trying to act distracting and entertaining, so the business side wouldn’t realize it was being held hostage by a drunk.

I showered, shaved and slicked my hair back with Bumble and bumble Hair Grooming Creme. Then I ran the blowdryer over my head. Afterward, I arranged my hair in such a way that it appeared casual and carefree. A wisp of hair falling across my forehead, which I froze in place with AquaNet. After having gone on more fashion shoots than I care to count, I’ve learned that terminally unhip AquaNet is the best. The result was hair that looked windblown and casual—unless you happened to touch it. If you touched it, it would probably make a solid knocking sound, like wood.

I sprayed Donna Karan for Men around my neck and on my tongue to oppose any alcohol breath I might have. Then I walked to the twenty-four-hour restaurant on the corner of Seventeenth and Third for a breakfast of scrambled eggs, bacon and coffee. The fat, I figured, would absorb any toxins.

As a backup safety measure, I swallowed a handful of Breath Assure capsules and wore a distracting, loud tie.

Everyone somehow arrives precisely at once, even though they all came from different places. I make a mental note: read Carl Jung. I need to understand synchronicity. Maybe I can use it in an ad someday.

I shake hands and greet people with an unusual amount of energy and enthusiasm for nine o’clock in the morning. I hold my breath when I face people and exhale when I turn away. I make sure that I stay at least ten paces ahead of everybody else. The group is small: my Fabergé client—a petite young woman who wears handcrafted needlepoint vests, the account executive and my art director, Greer.

Greer and I have been a “creative team” for five years. She’s been getting a bit bitchy lately about my drinking. “You’re late for work . . . you look disheveled . . . you’re bloated . . . you’re always impatient. . . . ” The fact that I’ve missed a few important presentations hasn’t helped matters. So I told her recently that I’d cut my drinking way back. Almost to nothing. To this day, Greer has never forgiven me for calling one of our clients at home at two in the morning and initiating phone sex. I was in a blackout at the time, so I am spared the actual memory.

As we walk into the first room of the exhibit, I cruise to the display case in the center of the room. I pretend to be interested in the egg that’s illuminated by four spotlights. It’s hideous; a cobalt blue egg smothered with gaudy ropes of gold and speckled with diamonds. I walk around the case, looking at it from all sides, as though I am intrigued and inspired. What I’m really thinking is, how could I have forgotten the words to The Brady Bunch?

Greer approaches me with a quizzical look on her face, quizzical not as in curious, but quizzical as in disbelief. “Augusten, I think you should know,” she begins, “the entire room reeks of alcohol.” She waits a beat, glaring at me. “And it’s all coming from you.” She crosses her arms over her chest, angrily. “You smell like a fucking distillery.”

I steal a glance at the two other members of our group. They’re huddled in a far corner of the room, looking at the same egg. They appear to be whispering.

“I even brushed my tongue. I took half a box of Breath Assure,” I tell her defensively.

“It’s not your breath. It’s coming out your pores,” she says.

“Oh.” I feel betrayed by my body chemistry. Not to mention my deodorant, cologne and toothpaste.

“Don’t worry,” she says, rolling her eyes. “I’ll cover for you. As usual.” Then she walks away. Her heels sound like ice picks on the marble floor.

As we continue through the museum, I feel two things. On the one hand I’m depressed and feel like a loser, having been caught in the act of being a lush. But on the other hand, it’s a huge relief. Now that she knows, I don’t have to make such an effort to cover up. This is the dominating emotion and at times, I almost feel giddy. Greer manages to keep the group away from me for the rest of the morning, so I am able to pretty much ignore the eggs and instead focus on the Met’s amazing use of recessed lighting, their beautiful hardwood floors. I feel inspired to make renovations to my apartment and am cataloguing ideas. At lunch we go to Arizona 206, a funky Southwestern place that elevates corn into cuisine.

Greer orders a glass of Chardonnay, something she never does. She leans over and whispers in my ear. “You should order a drink too. In case nobody else noticed at the museum that you reek. So this way, if somebody gets too close to you and smells the liquor, they’ll think it’s from lunch.”

Greer. Forty-five-minutes-per-day-on-the-treadmill, no-saturated-fat, alcohol-is-bad-for-you Greer is so rational. I, on the other hand, am living proof of the chaos theory. To oblige her, I order a double martini.

Somebody says, “Oh, well, since you two are being wild . . .” and the client and the account guy each order a light beer.

The rest of the day passes smoothly, groceries on a conveyer belt. Soon, I am home.

I’m so relieved when I walk in my door, so grateful to be home where I don’t have to hold my breath or explain myself that I have an immediate tumbler of Dewar’s. One drink, I tell myself. Just to calm my nerves from today.

After I finish the bottle, I decide it’s time for bed. It’s after midnight and I need to be at tomorrow’s global brand meeting at ten. I set two alarm clocks for eight-thirty and crawl into bed.

I wake up the next day seized by panic. I bolt out of bed and stumble into the kitchen where I look at the clock on the microwave: 12:04 P.M.

The answering machine is blinking ominously. Very reluctantly, I hit PLAY.

“Augusten, it’s Greer. It’s a quarter of ten, I was just calling to see if you’d left the house yet. Okay, you must be gone.”

Beeeeeeeeeeep.

“Augusten, it’s ten o’clock and you’re not here. I hope you’re on your way.”

Beeeeeeeeeeep.

“It’s ten-fifteen. I’m going into the meeting now.” In this last message her voice had a hard, knowing edge to it. An I’m-through-with-you-motherfucker edge.

I shower and throw on my suit from yesterday as fast as I can. I don’t shave but that’s okay I figure since I have light facial hair anyway and besides, looking a little scruffy seems sort of Hollywood-ish. I walk outside and hail a cab. Naturally, it’s red lights all the way uptown. And as I step into the lobby of my office building, my forehead is soaking wet, despite the mild May temperature. I swipe my sleeve across it and then get into the elevator and stab the button for my floor: thirty-five. The button doesn’t light up. I stab it again. Nothing. A woman steps into the elevator, pushes thirty-eight and her button lights up. The doors slide shut and she turns to me. “Whew,” she says, “you just get back from a five-martini lunch?”

“No, I overslept,” I say, instantly realizing how bad that sounds.

Her smile fades and she looks at the floor.

The elevator stops on my floor and I step out and walk down the hallway to my office. I toss my attaché case on the desk and take a tin of Altoids out of the front pocket. I crunch a handful of them while I try to think of an excuse. I stare out my window at the East River. I would give anything to be the guy on the tugboat who is pushing a garbage bin upriver. I bet he doesn’t have to deal with this kind of stress. He just sits at the helm, the wind rushing through his hair, the sun on his face. Perhaps he reminisces about his days sailing the North Atlantic, yellowed snapshots of his grandkids scotch-taped to the sun visor. Either that or he listens to Howard Stern, a warm can of Coors between his legs. Either way, his life is certainly better than mine. He certainly isn’t late for a global perfume meeting.

I decide to give no excuse, to just be as friendly as possible and become as involved with the meeting as I can. I will sneak in and take my place and say things that will make people believe I have been there all along.

I try the conference room door but it’s locked. “Shit,” I say under my breath. This means I’ll have to knock. And somebody will have to get up and let me in, thus foiling my plan to be invisible. So what I do is I knock very softly. This way, only the person closest to the door will hear me.

I knock and the door is opened. It is opened by Elenor, my boss, the executive creative director of the agency. “Augusten?” she says with surprise when she sees me. “You’re a little late.”

I see that the conference room is filled with suits. Twenty, thirty of them. And everybody is standing up, stacking papers in their briefcases, throwing their empty Diet Coke cans in the trash.

The meeting is just now ending.

I spot Greer over in the corner of the room talking with our Fabergé client. Not only my Fabergé client, but my Fabergé client’s boss, the product manager, the brand manager and the global head of marketing. Greer catches my eye and her eyes narrow into small and hateful slits.

I say to Elenor, “I know, I’m sorry to be late. I had a personal emergency at home.”

She scrunches up her face like she has just smelled a fart. She takes one step closer to me and leans in, sniffing. “Augusten, are you . . . drunk? ”

“What?” I say, shocked.

“I smell alcohol. Have you been drinking?”

My face flushes. “No, of course I haven’t been drinking. I had a couple drinks last night. But—”

“We’ll talk about this later. Right now, I think you should go over to the client and apologize.” She slips past me out of the room and her panty hose make an important hush, hush sound as she walks away.

I make my way over to Greer and the clients. They stop speaking the moment I appear. I manage a smile and say, “Hi, guys. I’m really sorry I missed the meeting. I had a personal matter that I had to attend to. I’m terribly sorry.”

For a moment, nobody says anything, they just look at me.

Greer comments, “Nice suit.”

I start to say thanks, but then it dawns on me that she’s being sarcastic because it’s the same suit I had on yesterday and looks like maybe it should have been taken to the cleaners a few weeks ago.

One of the clients clears his throat and checks his watch. “Well, we need to be going. We have to get to the airport.” They move past me as a group, all pinstripes, briefcases and itineraries. Greer pats each on the shoulder as they go. “Bye,” she says after them. “Have a great flight. Say hi to the baby, Walter. And Sue?” She beams. “I want the name of that acupuncturist next time I see you.”

A few moments later, Greer and I are in my office, “having a talk.”

“It’s not just about you. It’s about me, too. It reflects on me. We’re a team. And because you’re not holding up your half of the team, I’m suffering. My career is suffering.”

“I know. I’m really sorry. I’m just really stressed out lately. I honestly have cut way back on the drinking. But sometimes, well, I fuck up.”

Suddenly, Greer takes an Addy Award off my bookcase and hurls it across the room against the wall. “Don’t you fucking understand what I am fucking telling you?” she screams. “I’m telling you that you are bringing us down. You are destroying not only your career, but mine.”

Her rage is like a force in the room that flattens me into complete silence. I stare at the floor.

“Look at me!” she demands.

I look at her. Angry blue veins have erupted on her temples.

“Greer, look. I told you I was sorry. But you’re being ridiculous. This is not ruining anybody’s career. Sometimes people are late to meetings; sometimes they miss them. This shit happens.”

“It doesn’t happen constantly,” she spits. Her blond, icy bob is so perfect it irritates me. There is, literally, not a hair out of place and somehow this strikes me as insanely wrong.

Now I want to throw an Addy. At Greer. “Calm down, will you? Christ, you crazy bitch, this is insane. If I’m such a mess, explain why we’re so fucking successful,” I say, making a motion with my hand around the office as if to say, Look at all of this!

Greer glances at the shelf, then to the floor. She inhales deeply and then lets it out. “I’m not saying you’re not good,” she states more calmly. “I’m saying that you have a problem. And it’s affecting both of us. And I’m worried about you.”

I fold my arms across my chest and stare at the wall behind her, needing a break. It’s weird how my mind goes blank. I hate confrontation, despite the fact that I was raised with so much of it. My parents’ shrink was big on confrontation. He encouraged shouting and screaming, so you’d think I’d be better at it. But I just freeze up. So I stare at the wall and I’m not really thinking so much as feeling guilty, I guess. Like I’ve been caught. The thing is, I know I drink too much, or what other people consider too much. But it’s so much a part of me, it’s like saying my arms are too long. Like I can change that? The other thing that is starting to annoy me as I stare at the wall is that this is Manhattan and everybody drinks, and most people are not like Greer. Most people have more fun.

“So I drink a little too much sometimes. I’m in advertising. Ad people sometimes drink too much. Jesus, look at Ogilvy. They’ve got a fucking bar in their cafeteria.” And then I actually point at her. “You make it sound like I’m some bum in the Bowery.” Bums, I want to remind her, do not make six-figure salaries. They do not have Addy Awards.

She looks at me without any trace of uncertainty. She is unmoved by my comments. “Augusten,” she says, “you’re going down. And I’m not going with you.” She turns and walks out of my office, slamming the door hard behind her.

Alone in my office. It’s over. She’s gone. She’s probably right. Am I worse than I think? I get so angry all of a sudden, like I’m a kid and am being forced to stop playing and go to bed. My parents used to have parties when I was a kid, and I hated being sent to bed just when they began. I hated the feeling that I was missing everything. That’s why I ended up living in New York City, so I wouldn’t miss anything. That fucking bitch has ruined my day. I will be unable to concentrate on work at all today. Part of the reason Greer and I are such a good team is because we are fast. We cannot stand for something to be unresolved—so we work at a frenzied, concentrated pace to solve problems fast and come up with the right campaign. There are some creatives who will piss away days or weeks. But after a briefing, we get to work immediately and we always try to have four ideas within a day; then we can coast.

But her little scene means I don’t get my resolution. I get to stew. And this makes me hate her. And I can’t live with that, so I want to drink.

That night at home, I watch a video of my commercials. Even my old American Express stuff is cool after all these years, though I do regret the wardrobe decisions. Still, whatever our little problems, Greer and I have done some great work together. I can’t be that bad, I think as I check the level on my bottle of Dewar’s. There’s a third of a bottle left. Which means I’ve already had two-thirds of a bottle. Which doesn’t seem like “a problem” to me. People often drink a bottle of wine with dinner. It’s just not so unusual. And anyway, I’m a big guy: six-foot-two. Besides, I’m almost twenty-five. What else are you supposed to do in your twenties but party? No, the problem is that rigid Greer obviously has control issues. And she’s judgmental.

Another problem is that I am thinking these things while perched on the edge of my dining room table, which I never use for dining, but as a large desk. And when I reach for the bottle of Dewar’s to refill my glass, I lose my balance and fall over on the floor, smashing my forehead against the base of my stereo speaker.

There is a gash and there is blood. More blood, really, than the gash calls for. Head wounds are so dramatic.

I finish the bottle and still do not have that sense of relief that I need. It’s like my brain is stubborn tonight. So I have some bottles of hard cider and these gradually do the trick and I get my soft feeling. I lose myself on the computer, at porn sites. It’s weird that no matter how drunk I get, I can always remember my Adult Check password.

The next day, I am summoned to Elenor’s office. It is on the forty-first floor and has floor-to-ceiling glass, polished blond hardwood floors, a glass-topped table with beveled edges and chrome legs. It would be austere except for the leopard-print chair behind the desk which lets you know the person in this office is “creative.” I have a beautiful view of the Chrysler Building’s spire. Because Elenor is sitting behind her desk and talking on the phone, the spire appears to be coming out from the top of her head like a horn. Which is apt. She motions me in.

Once I am inside her office I see that we are not alone. Standing against the far left wall of the office, as if they had been hiding from my view until I was inside, are Greer, Elenor’s asshole partner, Rick, and the head of human resources.

Elenor hangs up the phone. “Have a seat please,” she tells me, pointing to the chair in front of her desk.

I look at her, then the chair, then the others in the room. All is eerily quiet. I feel as if I have walked into the room during the Nuremburg proceedings. “What’s going on in here?” I say warily.

“Close the door,” Elenor says, but not to me. She says it to them. Rick steps away from the wall and closes the door.

I have a feeling I know what this is about, but at the same time I think it can’t possibly be what I’m thinking. What I’m thinking is too unthinkable. This can’t be about my drinking.

Again, Elenor tells me to sit. Finally, I do. And Greer, Rick and the human resources woman all move in unison to the large sofa.

“Greer?” I say. I want to hear the magic words: “Nightmare of a pitch, get ready,” or something worse, “Guess which account we just lost.” Except I know she will not say these things. And she doesn’t. She looks down at her shoes: polished Chanel flats with interlocked gold Cs. She says nothing.

Elenor rises from her chair and walks around her desk. She stands before me and then sits back on the edge of her desk, clasping her hands in front of her. “Augusten, we have a problem,” she begins. Then in a rather light and playful tone she adds, “That sounds almost like an insurance commercial, doesn’t it? ‘Nan, we have a problem. These sky-high premiums and all this confusing paperwork . . . if only there was an easier way.’ ” Her smile dies and she continues. “But seriously, Augusten. We do have a problem.”

So if she’s joking, maybe I am crazy and this is nothing. I feel like I’m in a department store and I’ve just pocketed a keychain flashlight and the security guard comes over to me and asks the time. Am I going to get off?

“It’s your drinking.”

Fuck. Greer, you cunt. I don’t look at her. I continue looking right at Elenor, and I don’t blink. A person with a drinking problem would deny it, would shout or create a scene right at this moment. But I smile, very slightly, like I am listening to some client’s stupid comments on a commercial.

“You have a drinking problem and it’s affecting your work. And you’re going to need to do something about it immediately.”

Okay, I need to slow things down a little. “Elenor, is this about being late to that meeting yesterday?”

“Missing the global brand meeting yesterday,” she corrects. “And it’s not just that. It’s many, many instances where your drinking has had an effect on your performance here at the office. I’ve had clients speak to me about it.” She waits a beat to let this sink in. “And your coworkers are concerned about you.” She motions with her head to the sofa, in the direction of Greer. “I myself have smelled alcohol on you numerous times.”

I feel tricked by these people. They have nothing better to do than obsess over how many cocktails I have? And Greer, she just has to control everything, has to get her way. Greer doesn’t like that I drink, so all of a sudden my drinking is a big agency affair. Greer wants me to drink diet soda, I will be forced to drink diet soda.

“Right now, as one example,” she says. “I can smell alcohol on you right now. But there have been other things. That shoot we had last year in London where you took the train to Paris for three days and nobody heard a word from you.”

Oh, that. My Lost Weekend in Paris. I’d done my best to forget what little I remembered. Still, I dimly recall a young sociology professor with a soul patch, which is that little tuft of hair under the bottom lip, which I had never heard of before him. That much I remember. But really, so what? The commercial got shot.

“This isn’t about just one thing here and there. It’s about a progression of behaviors. And it’s about our clients. Because more than one has spoken to me. See, Augusten, advertising is about image. And it just doesn’t look good to have a creative on the account who misses meetings, shows up late, shows up drunk or smelling like alcohol. It’s just not acceptable.” Framed behind her head is the Wall Street Journal ad profiling her. The headline reads, MADISON AVENUE, ACCORDING TO ELENOR.

It’s horrible, but I immediately think I can’t wait to tell Jim about what’s happening right now, when we have drinks later. Thinking this makes me accidentally smirk.

Greer gets off the sofa and stands next to Elenor. “It’s not a joke, Augusten. It’s serious. You’re a mess. Everybody knows it. I knew the only way to get through to you would be to have an intervention.” She is trembling, I see. Her bob is quivering ever so slightly.

The human resources woman speaks up. “We feel that it would be in your best interest for you to admit yourself into a treatment center.”

I look at her, and realize I hardly recognize her without a stack of paychecks in her hand. Next to her, Rick is doing his best imitation of somebody who is not a psychopath. He looks at me with such sincere concern and compassion that I want to harm him with a stick. Rick is the most insincere, backstabbing person I have ever met. But he fools everyone. They are all tricked by his kindness. It’s amazing how shallow advertising people truly are. Rick is a Mormon and although this is not a reason to hate him, I hate all Mormons as a result of knowing Rick. I want to say, what’s he doing here? But I don’t because he’s Elenor’s partner and they are a team, like me and Greer, only they are also my bosses.

The human resources woman drones on. “There are many treatment options, but we feel a residence program would be the best course of action under the circumstances.”

Oh, now, this is just way over the top. “Are you saying I need to go to rehab?”

Silence, but nods all around.

“Rehab?” I say again, just to make sure. “I mean, I can cut back on my drinking. I do not need to leave work and go to some fucking rehab.”

More solemn nods. There’s a thick tension in the room. As if everyone is ready to pounce and restrain me should I break out in a rash of denial.

“It would only be for thirty days,” the human resources woman says, as if this fact is supposed to somehow comfort me.

I feel this incredible panic and at the same time, I am certain there is nothing I can do. The thing is, I recognize what’s happening here, have seen it before in meetings when I am trying to sell a campaign to a client that they will never, never, never buy.

I will either have to quit right now and find another job or I will have to go to their ridiculous rehab. If I quit, I’m sure I can get another job. Pretty sure. Except advertising is sort of a small world. And I just know that Rick would be on the phone in five minutes calling everybody and telling everybody in the city that I’m a drunk who refused to go to rehab, so I quit. And really, what could happen? It’s actually possible I could be without a job. Even though I make way too much money, I still live paycheck to paycheck, so I would actually be broke. Like the bum that Greer already thinks I am.

It’s simple: I lose. “Okay,” I say.

Every shoulder in the room relaxes. It’s as if a valve has been released.

Elenor speaks up. “Are you saying you’ll agree to a thirty-day stay in a treatment center?”

I glance over at Greer, who is looking at me expectantly. “It doesn’t really seem like you’re giving me a choice.”

Elenor smiles at me and clasps her hands together. “Excellent,” she says. “I’m very glad to hear this.”

The human resources woman rises from the couch. “There’s the Betty Ford Center in Los Angeles. But Hazeldon is also excellent. We’ve had many people check into Hazeldon.”

Roaches check in but they don’t check out is what I want to say. And then I remember the priest. It was about three years ago and he was giving me a blowjob in the back of his Crown Victoria. I was drunk out of my mind and couldn’t get it up. He told me, “You really should check yourself into the Proud Institute. It’s the gay rehab center in Minnesota.”

So maybe I should do this instead. The guys will definitely have better bodies at a gay rehab hospital. “What about Proud Institute?” I say.

The human resources woman nods her head politely. “You could go there. It’s, for, you know, gay people.”

I look at Rick and he has turned away because he hates the word gay. It’s the only word that can crack his veneer.

“That might be better,” I say. A rehab hospital run by fags will be hip. Plus there’s the possibility of good music and sex.