17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

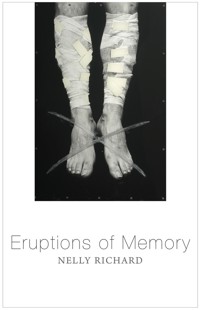

In this important book, one of Latin America’s foremost critical theorists examines the use and abuse of memory in the wake of the social and political trauma of Pinochet’s Chile. Focusing on the period 1990–2015, Nelly Richard denounces the politics and aesthetics of forgetting that have underpinned both the protracted transition out of dictatorship and the denial of justice to its survivors and victims.

What are the perils and social costs of a culture of forgetting? What forms do memories of injustice take in newly formed democracies? How might a history of violence and an ethics of reparation be reconciled in post-autocratic societies? In addressing these and other questions, Richard exposes the abuses of the past and the present while also attending to the residues of memory that are manifested in street protests, literature, and the media, and in artistic practices from architecture and urban design to installation and film. While cultural artifacts can be powerful devices for resistance and critique, Richard argues that they can also be complicit in reproducing and collaborating with forms of institutional and political oblivion. Both within Chile and beyond, Richard offers a trenchant critique of how authoritarian regimes and neoliberal states whittle away at memory’s critical capacity. At a time of seismic political realignments in Latin America and internationally, Eruptions of Memory makes a powerful case for the ethical, political, and aesthetic value of memory.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Series Title

Title page

Copyright page

Acknowledgments

Translators’s Note

Introduction: The Struggle for Words – Graciela Montaldo

Against the dictatorship, the avant-garde

Eruptions of Memory

Bibliography

Notes

Prologue

Notes

1: Traces of Violence, Rhetoric of Consensus, and Subjective Dislocations

Memory and disaffection

Biographical ruptures, narrative disarticulations

The presence of the memory of absence

Notes

2: Women in the Streets: A War of Images

The return and revolts of the past

Uproar in the streets

The war of images

Notes

3: Torments and Obscenities

The blackmail of truth: bodies and names

Obscenity I

Perpetual betrayal

Obscenity II

Conversion

Silence, screams, and the printed word

Memory and market

Obscenity III

Notes

4: Confessions of a Torturer and His (Abusive) Journalistic Assemblage

The scene of the interview

The scene of torture

Notes

5: Coming and Going

Reconstructing the scene

The fissures of heroic memory

Notes

6: Architectures, Stagings, and Narratives of the Past

Villa Grimaldi

The Cementerio General de Santiago: memorial of the disappeared

The Bulnes Bridge

Londres 38

The Museum of Memory and Human Rights

Notes

7: Two Stagings of the Memory of YES and NO

The mimesis of memory

Theater of antagonisms

Notes

8: Past–Present: Symbolic Displacements of the Figure of the Victim

Notes

9: Media Explosion of Memory in September 2013

Traces and the archive: the last time …

The bombing of La Moneda

Strategies of memory, the power of images, and media control

Testimonies, revelations, and anti-confessions

Notes

10: Commemoration of the 40th Anniversary of the Military Coup … and Afterwards

History, memory, and countermemories

The contortions of memory

Notes

Bibliography

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Start Reading

1: Traces of Violence, Rhetoric of Consensus, and Subjective Dislocations

Pages

ii

iv

vii

viii

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

xix

xx

xxi

xxii

153

xxiii

xxiv

xxv

xxvi

154

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

155

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

156

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

157

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

158

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

159

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

160

161

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

162

163

164

165

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

166

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

167

168

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

Series Title

Critical South

The publication of this series was made possible with the support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Nelly Richard, Eruptions of Memory

Copyright page

First published in Spanish as Latencias y sobresaltos de la memoria inconclusa (Chile 1990–2015) © Eduvim, Villa María, 2017, 1st ed.

This English edition © Polity Press, 2019

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-3227-8

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-3228-5 (pb)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Names: Richard, Nelly, author. | Richard, Nelly. Critica de la memoria, 1990-2010.

Title: Eruptions of memory : the critique of memory in Chile, 1990-2015 / Nelly Richard.

Description: Cambridge, UK ; Medford, MA, USA : Polity Press, [2018] | Compilation of essays, many of which originally published in: Critica de la memoria, 1990-2010. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018019581 (print) | LCCN 2018034584 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509532308 (Epub) | ISBN 9781509532278 | ISBN 9781509532285 (pb)

Subjects: LCSH: Collective memory--Political aspects--Chile. | Protest movements--Chile. | Political violence--Chile. | Politics and culture--Chile. | Chile--History--1988-

Classification: LCC F3101.3 (ebook) | LCC F3101.3 .R534 2018 (print) | DDC 306.20983--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018019581

Typeset in 10.5 on 12.5pt Sabon

by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NL

Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Acknowledgments

Many people have contributed to this project, amongst them Andrew Ascherl, who has produced a careful and attentive translation; Sergio Villalobos-Ruminott (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA) and an anonymous reader who reviewed the translation; and Graciela Montaldo (Columbia University, USA), who wrote the introduction, and Julia Sanches who translated it. At Polity, Sunandini Banerjee created a beautiful cover design and Neil de Cort oversaw the production process. The project was expertly managed by Paul Young at Polity and Ozge Kocak and Tristan Bradshaw at Northwestern University, USA. In addition, Penelope Deutscher (Northwestern University), thoughtfully shepherded the publication through its various stages.

The International Consortium of Critical Theory Programs gratefully acknowledges the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for its support through grants to Northwestern University and the University of California, Berkeley, which have made possible the translation and publication of Nelly Richard’s Latencias y sobresaltas de la memoria inconclusa (Eruptions of Memory) as part of the Consortium’s Critical South series. Those involved in Eruptions of Memory thank the international editorial board of Critical South: Natalia Brizuela, Co-Chair (University of California, Berkeley, USA), Judith Butler, ex officio (University of California, Berkeley, USA), Gisela Catanzaro (Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina), Victoria Collis-Buthelezi (WiSER, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa), Souleymane Bachir Diagne (Columbia University, USA), Rosaura Martínez (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico), Leticia Sabsay, Co-Chair (London School of Economics and Political Science, United Kingdom / Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina), Vladimir Safatle (Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil), Felwine Sarr (Université Gaston Berger de Saint-Louis, Senegal), and Françoise Vergès (Collège d’études mondiales, France).

Finally, the project would not of course have been possible without Nelly Richard herself, who kindly made available the pre-published Spanish-language edition of the work and provided valuable assistance. Collaborating with several parties listed above, she nominated the translator and translation reviewer, liaised with her publisher, and provided the images that appear in this edition.

Anna Parkinson, Northwestern University

Translator’s Note

A number of the citations in the original Spanish edition of this book refer to texts originally published in languages other than Spanish. I have endeavored in all of these instances to use published English translations (or the original English text as the case may be). All translations of Spanish language sources for which no published English translation is available are my own. Any explanatory end notes that I have added to this translation appear in square brackets [ ] and are signed “—Tr.”

AA

Introduction: The Struggle for WordsGraciela Montaldo, Columbia UniversityTranslated by Julia Sanches

In Latin America, and especially in the Southern Cone, the 1970s were the setting for the greatest political and symbolic disputes of modern history. The emancipatory projects of revolutionary and grassroots movements and of the Leftist guerrillas that had been operating in the region since the 1960s (emboldened by the Cuban Revolution of 1959) were quashed by the brutal military and paramilitary repressions that began with the establishment of a civilian-military dictatorship in Uruguay on June 27, 1973. This was soon followed by a coup d’état in Chile, in which General Augusto Pinochet unseated Salvador Allende, the country’s democratically elected president, on September 11, 1973. A handful of years later, on March 24, 1976, another military coup led to the foundation of a dictatorial government in Argentina. It was not long before the entire region fell under military rule (Brazil had been a dictatorship since 1964, and Bolivia and Paraguay each had decade-long dictatorships throughout the twentieth century). The dictatorial governments of these countries coordinated joint campaigns of repression under the umbrella of “Operation Condor,” which counted on strategic support from the United States. These coups d’état were more than just new chapters in a long history of military interventions in the subcontinent’s political life. Brutal repression, violence, disappearances, torture, and concentration camps that held thousands of detainees were all ways of breaking the people’s will for radical change, and the cruelest form of domesticating citizens in order to pave the way for neoliberal and authoritarian policies that curbed people’s rights and left many living in poverty.

Not only did the military coups of the 1970s interrupt democratic processes, they also imposed on society a new economic, political, and cultural model, implementing through it dynamics of repression and anti-politics. Class struggle – a historically active mode across Latin America – dwindled, social organizations were demobilized, and institutions (political parties, organizations, unions, grassroots groups, and student movements) were dismantled. Workers, grassroots militants, and guerrilla fighters were rounded up in torture and detention camps alongside artists and intellectuals. All were affected by this brutal repression, which brought harm to the most destitute and to young middle-class militants in equal measure. For the politically progressive who were not disappeared, killed, or driven into exile, day-to-day survival under these conditions of terror begat a sort of double life: public life – silenced and devoid of political activity, except for some early human rights activism – and private life – in which they sought to preserve and reproduce critical thought and intellectual activity. Seeing in culture and art an enemy as dangerous as workers’ rights movements and armed factions, military regimes attempted to tear down cultural networks by interfering in universities, censoring writers and their works, shutting down magazines and publishing houses, and imposing a widespread censorship that, of course, ended inevitably in self-censorship. Social practices were especially affected by the market’s centrality and by the consumer policies dictated by neoliberal politics.

How was survival possible in those years? And, most of all, how did progressive society manage to reconstitute its ties and networks of solidarity and critique? In Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay, the small groups of intellectuals who remained played a decisive, dual role against their countries’ respective military regimes: on the one hand, they would stand against the dictatorship – that is, they would reject the homogenizing discourse that aimed to suppress all divergent thinking; on the other, they would generate new systems of social exchange, bonds of solidarity, and social ties within dismantled societies whose cultural and political networks had been seriously impaired, and in which the market generated new mediations.

Southern Cone intellectuals and artists who created works during these dictatorships were the product of complex cultural experiences. In many cases, such as the case of Chile, these experiences intersected with the militancy of Leftist political parties and organizations, which carried out community services in traditionally excluded sections of society. Up until the 1970s, the Latin American Left had forged a symbolic alliance between artists, intellectuals, and the revolutionary subject par excellence, the people (an alliance that stemmed from populist movements). This alliance had found its definitive form in the Cuban Revolution and in the thinking of Che Guevara: “And to the professors, my colleagues, I will say the same: we must paint ourselves as blacks, mulatos, workers, farmers; we must go to the people, we must tremble with the people …”1 Dictatorships broke this sense of identification, and so the Left entered a process of profound self-reflection.

In the depths of their respective dictatorships, surviving artists and intellectuals began to contemplate new strategies of intervention and political positioning. The ideas of the people, of intellectuals, artists, and militants were subjected to critique, as was the system of political legitimation. In Chile, Nelly Richard played a relevant and unique role in defining the new position of art, artists, and intellectuals within dictatorial contexts, and in rethinking cultural practice in regimes of terror. The impact of her work was and remains enormous, not only in Chile, her adopted country (Richard was born in Caen, France, in 1948), but throughout Latin America. Her discourse not only appealed to art critics, philosophers, and social thinkers, but also to artists, writers, and curators. Her theoretical interventions changed the thrust of the discussions surrounding gender, art, memory, and politics in Latin America.

Against the dictatorship, the avant-garde

Nelly Richard settled in Chile in 1970, when the government of the Unidad Popular party (Popular Unity) came to power, with Salvador Allende as the country’s president. Soon after her arrival, she held a position as the visual arts coordinator of the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes. After Pinochet’s coup d’état in 1973, Richard was removed from her position at the museum and, a few years later, in the late 1970s, became one of the most active intellectuals of what would later be referred to as the “Escena de Avanzada.” The “Escena de Avanzada” consisted of a group of intellectuals and artists who, though different, were united by two premises: a radical opposition to the dictatorship, and an engagement with experimental aesthetic practices through avant-garde pursuits and the development of critical thinking. Richard had created a new, highly complex theoretical discourse which, rooted in a specifically Chilean context, aimed to provide an account of new political and cultural experiences. She opened up a space for debates on dictatorships, repression, censorship, victims’ memories, the resignification of Leftist thought, the reorganization of feminist thought and gender issues, the aesthetic avant-garde within contexts such as that of Latin America, and the new space occupied by the market and consumerism in Chile. All of these experiences have in common the idea that intellectual and artistic practice have a political function that must, in turn, have a political effect in the public sphere. As such, the entirety of Nelly Richard’s work can be read as an exploration of the relationship between aesthetics, culture, and politics, as is clear from the titles of most of her books. Neither nostalgic nor naive, her examination is carried out by way of a strong theoretical approach and through a search for categories and discourses which allow local experiences to be invested with new meanings. Her relationship with theory rejected the colonial model (which in Latin America had reproduced the thinking of hegemonic centers). In its place, Richard’s theoretical practice gave rise to reflections on local phenomena while drawing on international critical thought. Richard also developed the concept of theory as a form of resistance against the widespread notion that reality could be easily represented in a manner that was “informative-communicative of immediate linguistic decoding” (Crítica y política, 163). This meant rejecting any interpretations put forth by the media that, coopted by the dictatorship, endorsed the image of model citizens as disciplined consumers. Regarding gender issues, Richard reoriented the traditional feminist debates in Latin America. Her work questioned the idea of gender as an identity to rethink feminism in the more general frame of oppression and dictatorial powers. In this context, the feminine would be a complex product of the mechanisms of appropriation, disappropriation, and contra-appropriation of the hegemonic practices. In Latin America, feminism used to be the result of activism and practical interventions in the public sphere. Richard introduced a strong theoretical approach. In doing so, she reappropriated a masculine tool (theory) and resignified the historical battles of women paying attention to the symbolic dimension.

After the experiences of the Latin American Left between the 1960s and early ’70s, Richard’s approach revisited and reworked the connection between culture and politics. It was no longer a matter of thinking politics as content and ideological discourse, but instead as a practice that ran permanently against the common sense of power, against institutions’ (universities, museums, galleries, publishing houses, political parties) comfort zones, against the media’s homogenization, against fixed subjectivities. Intellectuals and artists were the ones who, within this model, would have to generate interferences (in perception and thought), and question society, power, and community – not with political party slogans but through an act of permanent dislocation and critique. The discourse and aesthetics of the “Escena de Avanzada” rejected the notion of communicative transparency. The group’s work was experimental; their critical discourse extremely theoretical and, at times, hermetic and opaque. Richard operated in the group as a sort of magnet, creating new meanings, introducing new topics, and directing the varying aesthetic practices toward the avant-garde. In this way, she resignified the role of curators and critics as sites for the production of discursivity, in collaboration with artists’ creative work.

Members of the “Escena de Avanzada” worked across genres (visual arts, literature, poetry, video, cinema, critical texts) and expanded art’s technical tools toward intermediality and the shifting dynamics of the processes of the city and the living body. The group grew out of the initiative of visual artists (Carlos Leppe, Eugenio Dittborn, Catalina Parra, Carlos Altamirano, the Colectivo de Acciones de Arte – or Art Actions Collective, otherwise known as CADA – Lotty Rosenfeld, Juan Castillo, Juan Dávila, Víctor Hugo Codocedo, Elías Adasme, among others) and their engagement with the written works of Raúl Zurita (poetry) and Diamela Eltit (prose); it also involved the participation of philosophers and sociologists such as Ronald Kay, Adriana Valdés, Gonzalo Muñoz, Patricio Marchant, Rodrigo Cánovas, and Pablo Oyarzún, among others.

The “Escena de Avanzada” was developed as an artistic avant-garde and was criticized for its emphasis on experimentation and theoretical discourse (drawing particularly on intellectuals such as Michel Foucault, Julia Kristeva, Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, and Jacques Derrida). Chilean philosopher Willy Thayer voiced one of the more interesting polemics generated by the “Escena de Avanzada,” arguing that the group’s experimentation was complicit in Pinochet’s dictatorial regime. The main point of his argument was that the group could not generate any real opposition to the dictatorship because the coup d’état had laid the foundation for its own rules of opposition, which allowed for the existence of an isolated avant-garde with little social intervention.2 Richard took this objection seriously, responding: “This would mean that nothing exists outside the system and that, by extension, any act of criticism will always be implicated in the structures of power within which it seeks to generate disruptions of meaning” (Crítica y política, 37). In this sense, Richard’s conception of the intellectual/artist is as a conspirator, as an entity operating within the system by employing some of its mechanisms, but instead using them against power, thus generating unrest, performing small acts of violence, shorting circuits, creating disconnections. The impact of Richard’s first books may be described in similar terms. Márgenes e Instituciones. Arte en Chile desde 1973. Escena de avanzada y sociedad is a seminal study of the radical “Escena de Avanzada” artists and their function in dictatorial Chile (first published as a special issue of the Australian journal, Art and Text, in 1986).3 In La estratificación de los márgenes. Sobre arte, cultura y política/s (1989), her second book, Richard analyzes new cultural practices, criticizing, precisely, their capacity for reification and institutionalization, and calling attention to the need to keep all emancipatory potential alive. Richard describes her interventions during that period with great clarity:

The [Escena de] Avanzada responded to the annihilating nature of the military coup with a counter-coup, a barrage of images, materials, techniques and significations that explored forms of critical resistance in the face of totalitarian violence by mixing with the present, that is, by devising process and relational works (works that are not static, but ongoing and situational), whose openness, and in which the ephemerality of their signs allowed them to bypass – from the perspective of the living body, of biography or the city – the closure of what is finite and definitive in dead time, which is what grants museum paintings their eternity. (Crítica y política, 159)

The “Escena de Avanzada” remained very active throughout the 1980s.

The year 1990 was critical to Chilean history: after seventeen years of military rule, elections were held; a new phase began and, with it, a new government of “conciliation” (consensus) led by Patricio Aylwin. This change would have profound consequences for Nelly Richard’s work, as she saw the onset of democracy as a challenge to her continuing critical practice. That year, she would found and edit the influential magazine Revista de crítica cultural, which appeared continuously until it ceased publication in 2008, with a total of thirty-six issues published. The magazine introduced the expression “cultural critique” as a form of repositioning oneself in relation to sociological approaches to culture and to the advance of cultural studies in American academia. By then, Richard was no longer just a critical/theoretical point of reference in Latin America; her colleagues in Latin American studies at US universities were starting to be drawn to the novelty and radicalness of her interventions. Although Richard spoke from the Left, she nonetheless questioned the essentialist tradition of politics and contemplated contemporary society through the lens of new subjectivities, all in a sophisticated theoretical language. Unlike other intellectuals living in Latin America, Richard did not fashion her position in Chile – in the “margins” – into a place of power, but instead positioned it as a place for dialogue, debate, inquiry. Similarly, while the Revista de crítica cultural was still under her purview and backed by a group of intellectuals, Richard called on many younger people from different countries to join them in generating critical dialogues.

Throughout the 1990s, Richard published three influential books in Chile: Masculino/Femenino. Prácticas de la diferencia y cultura democrática in 1993, La insubordinación de los signos (Cambio político, transformaciones culturales y poéticas de la crisis) in 1994, and Residuos y metáforas (Ensayos de crítica cultural sobre el Chile de la transición), written with the support of a Guggenheim grant, which she won in 1996, and published in Spanish in 1998. Like most of Richard’s work, these books are made up of fragmented texts that simultaneously introduce new topics and debates while theoretically interrogating knowledge that was beginning to become institutionalized as the country underwent a transition to democracy. Along with the Revista de crítica cultural, whose highly avant-garde design – visually dynamic, it had a complex way of drawing readers in through the use of different fonts and the superimposition of images and texts that made reading it a kind of “work” – these three books went against what Richard refers to as “the linguistic tyranny of simplicity, directness, and transparency” (Crítica y política, 24). With the Revista de crítica cultural, Richard had wanted, in her own words, to “jolt the content of the theoretical pieces with graphic layouts that de-centralized their reading in favor of a reflexive visuality – far from all illustrative subordination – such that they could behave like just another text” (Crítica y política, 29).

In 2003, Richard and other intellectuals convened an international symposium to debate the status of culture thirty years after Chile’s military coup. In her presentation of the event, she laid out the thrust of the debates: the relationship between art and politics. Richard sustained that the relationship between these had been historically shaped by two modes: socially engaged art and avant-garde art. Of course, her preference was for avant-garde art: “Unlike militant art, which purports to ‘illustrate’ its engagement with a political reality that is already invigorated by the forces of social transformation, avant-garde art aimed to anticipate and foreshadow change, using aesthetic transgression as an anti-institutional detonator” (Arte y política, 16). This statement also helps us to understand her critical work, which always sought to disrupt established meanings. Notwithstanding this penchant for disruption, Richard’s writing continued to search for meaning in social practice, including aesthetic practice. Her contention with postmodernism, which had become widely popular in the social sciences and humanities of 1980s’ Latin America, resides precisely in its commitment to cultural interpretation from the point of view of a deproblematized (postmodern) relationship with new trends in art and culture. For Richard, the search for meaning is always political; it requires the disruption of conventions and the existence of a kind of political, but also aesthetic, engagement with discourse that resists the temptation of linguistic transparency. Searching for meaning does not mean communicating clearly; on the contrary, it is a process within which arguments are made increasingly complex and ideas problematized. Richard’s books are not straightforward but are committed to generating dialogue and creating a relationship with readers and with other texts that give rise to conflicting views on the social. Herein resides the political dimension of this critical practice, which Richard prefers to refer to as “the political of” (rather than “the politics of”) arts and culture.

The following works by Richard continue this line of thought. There is the edited volume of Arte y política (2005) the symposium on the thirty years that followed Pinochet’s coup; Fracturas de la memoria. Arte y pensamiento crítico (2007); Feminismo, género y diferencia(s) (2008), in which she looks again at her critical reflections on gender theory in the context of new policies of social inclusion; Crítica y política (2013), an extensive interview that Richard rewrites in order to run through the fundamental themes of her work; and Poéticas de la disidencia/Poetics of Dissent (2015), a catalogue of the curatorial work she conducted on Chile’s Pavilion at that year’s Venice Biennale. One can trace a certain continuity in these works, not only in terms of their subject matter, content, and the issues raised therein, but also in that they contain an interpretative logic that runs counter to common sense (her dissident perspective is tireless), and a desire for intellectual engagement with critical thought that operates permanently against institutionalization and draws on other traditions of emancipation. Her books are all framed by a fragmentary perspective that, instead of moving toward a totalizing narrative, examines objects that might otherwise seem minor. The strength of her discourse lies in its disruption of official, overarching narratives, not with the aim of rendering them trivial through counter-narrative, but of revealing their fissures, in a way that is both deconstructive and grounded in political context.

On this note, it is worth mentioning that Richard has until now written her entire oeuvre in Spanish and, in so doing, has also, from this minority position – relative to the world of international theory – created a voice of dissidence with respect to the demands of the academic market. In creating spaces for dialogues and debates framed in different theoretical perspectives, she did so from a “situated” position, never losing sight of the fact that the objects in question are produced and circulate within a specific context and that critical voices inevitably take a stance; speaking from a position that is not aseptic nor indeterminate, these voices are instead heavy with the words of a specific community. Because of the significant impact Richard has had in the field of Latin American studies and American cultural studies, a number of her books have been translated into English (Masculine/Feminine: Practices of Difference(s); The Insubordination of Signs: Political Change, Cultural Transformation, and Poetics of the Crisis; Cultural Residues: Chile in Transition). By the late 1990s, Richard began to work actively in the Universidad de Arte y Ciencias Sociales (ARCIS), in Chile, where she taught classes, founded graduate programs such as the degree in cultural criticism, and worked as the university’s dean. Aside from her work at institutions, Richard continued, as always, to create new spaces in which to discuss current issues.

Eruptions of Memory

In 2010, Richard published Crítica de la memoria (1990–2010). This book is a statement on a pivotal subject in Chile during that time period: a society’s relationship with the memory of a dictatorship, with its traumatic and violent past, and with its present. Eruptions of Memory: The Critique of Memory in Chile 1990–2015 returns to certain topics already present in Crítica, but with a number of rewritten chapters and new, revised materials on memory and its resignifications throughout the country’s political history. To Richard, memory is inconclusive; it does not end, nor does it come to a close, because it is a political practice. The book begins by taking a definitive stance, in choosing how to refer to the period that began in 1990 when the first “democratic”4 government came to power. Politicians referred to the process as a “democratic transition”; Richard prefers the term “post-dictatorship,” therefore making it clear that the present remains anchored in that past, a past that continued to condition Chilean society. In this way, she brings into question the oversight that these new forms of power wanted to exert over the political process that had started with the elections. Her book also questions the idea of consensus as a model for national reconciliation – as expounded by Patricio Aylwin’s government (1990) – and the Chilean Transition’s official narrative of memory. During the 1990s, there was widespread debate throughout the Southern Cone on how to rethink dictatorial pasts – how to handle traumatic memories of violence, torture, the dismantling of a country’s social fabric, and the loss of its revolutionary horizon. It was also during this decade that debates on both the traumatic memory of the Holocaust and the future of the Left after the fall of the Berlin Wall were rekindled across the globe.

Richard posits a controversial relationship with these debates and pens a highly personal book that positions itself beyond critical consensus. She holds that all stories about the past, including testimonies by human rights groups, must be revised in order to disrupt crystallized meanings. Eruptions of Memory stands against reconciliation in order to propose, in its place, a critical relationship with the past; a relationship in which the past could not be reified and in which the many meanings of the historical trauma that had changed Chile forever would remain open. While Aylwin’s government conceived of a pacifying relationship with the past (and a large part of Chile approved of this tactic), Richard writes about what cannot be pacified (Chapter 1). However, she does so in fragments, selecting the objects of her pen from outside the overarching official narratives: the activation of memory during the detention of Pinochet in London (1998) and the media representation of the activism of pro- and anti-Pinochet women in Santiago streets (Chapter 2); the proliferation of testimonial texts of women who were tortured and of torturers (Chapters 3 and 4); the radical questioning of memory in the documentary films of Patricio Guzmán (Chapter 5); the architecture of memory and the resignification of official monuments throughout the inscription of the present in deterritorialized urban sites (Chapter 6); the publicity campaign for the 1988 plebiscite and the politics of images (Chapter 7); the updating of the dictatorial repression and the repression under democratic governments (Chapter 8); and the new theoretical challenges of the politics of memory forty years after Pinochet´s coup d'état (Chapters 9 and 10). Political readings do not have privileged objects of study but occur instead where there is discomfort, where social problems come into being. Richard sees aesthetic and intellectual practice as a matter of stance-taking and, therefore, as a struggle for the power to create meanings. Nevertheless, she distrusts the crystallization of meaning and supports a constant awareness of the present: “Criticism must demonstrate an awareness of the areas of greatest vulnerability and failures within the subsystem of which the dominant whole is composed so that interruptions can be generated, locally, altering the circuits of docile reproduction and integration” (Crítica y política, 37). Her entire unique and provocative oeuvre is contained within this maxim.

Bibliography

Avelar, Idelber.

The Untimely Present: Postdictatorial Latin American Fiction and the Task of Mourning

. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999.

Beasley Murray, Jon. “Reflections in a Neoliberal Store Window: Nelly Richard and the Chilean Avant-Garde.”

Art Journal

64/3 (Fall, 2005), pp. 126–129.

Del Sarto, Ana. “Cultural Critique in Latin America or Latin American Cultural Studies?”

Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies

9/3 (2000), p. 236.

Del Sarto, Ana.

Sospecha y goce: una genealogía de la crítica cultural en Chile

. Santiago de Chile: Editorial Cuarto Propio, 2010.

Guevera, Ernesto “Che.” “Discurso al recibir el doctorado honoris causa de la Universidad Central de las Villas.”

https://www.marxists.org/espanol/guevara/59-honor.htm

. January 2018.

Masiello, Francine.

The Art of Transition: Latin American Culture and Neoliberal Crisis

. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001.

Oyarzún, Pablo, Nelly Richard, and Claudia Zaldívar (eds.)

Arte y política

. Santiago de Chile: Universidad Arcis-Universidad de Chile-Consejo Nacional de la cultura y las artes, 2005.

Richard, Nelly

. Márgenes e Instituciones. Arte en Chile desde 1973. Escena de avanzada y sociedad

. Documento Flacso n. 46. Santiago de Chile: Ediciones Metales Pesados, 2007. (1st ed. Melbourne: Art and Text/Francisco Zegers, 1986.)

Richard, Nelly

. La estratificación de los márgenes. Sobre arte, cultura y política/s.

Santiago de Chile: Francisco Zegers Editor, 1989.

Richard, Nelly

. Masculino/Femenino. Prácticas de la diferencia y cultura democrática.

Santiago de Chile: Francisco Zegers Editor, 1993.

Masculine/Feminine: Practices of Differences(s)

, trans. Silvia R. Tandeciarz and Alice A. Nelson. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004.

Richard, Nelly

. La insubordinación de los signos (Cambio político, transformaciones culturales y poéticas de la crisis).

Santiago de Chile: Editorial Cuarto Propio, 1994.

Richard, Nelly

. Residuos y metáforas (Ensayos de crítica cultural sobre el Chile de la transición).

Santiago de Chile: Editorial Cuarto Propio, 1998.

Richard, Nelly

. Fracturas de la memoria. Arte y pensamiento crítico

. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI, 2007.

Richard, Nelly

. Feminismo, género y diferencia(s)

. Santiago de Chile: Palinodia, 2008.

Richard, Nelly

. Crítica de la memoria (1990–2010)

. Santiago de Chile: Ediciones Universidad Diego Portales, 2010.

Richard, Nelly

. Crítica y política

. Santiago de Chile: Editorial Palinodia, 2013.

Richard, Nelly

. Poéticas de la disidencia/Poetics of Dissent

:

Paz Errázuriz – Lotty Rosenfeld

. Santiago de Chile: Polígrafa, 2015.

Richard, Nelly

. Latencias y sobresaltos de la memoria inconclusa (Chile 1990–2015

). Córdoba: Eduvim, 2017.

Richard, Nelly and Alberto Moreiras (eds.)

Pensar en/la postdictadura

. Santiago de Chile: Editorial Cuarto Propio, 2001.

Thayer, Willy. “El Golpe como consumación de la vanguardia.”

Extremoccidente

2 (2003).

Notes

1

Acceptance speech of the Doctorate honoris causa, Universidad Central de las Villas (December 28, 1959).

https://www.marxists.org/espanol/guevara/59-honor.htm

(January 2018). Fidel Castro spoke to intellectuals using similar terms in his “Words to the Intellectuals” (1961).

2

You can read more about this controversy in Willy Thayer, “El Golpe como consumación de la vanguardia.”

3

An expanded edition – which included reflections on Richard’s book by the artists Norbert Lechner, Diamela Eltit, Pablo Oyarzún, Eugenio Dittborn, and others – was published in FLACSO in 1987.