Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

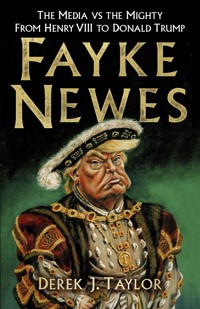

'Fake news.' 'Dishonest press.' 'Racist.' 'Mentally unstable.' The insults President Donald Trump and the American news media hurl at each other are nothing new. In Tudor England, printed papers branded the monarch a 'horrible monster' and were in turn accused of publishing 'false fables'. Ever since the invention of the printing press, those in power have seen mass communication as a dangerous threat that usurps their ability to tell people what to think and is capable of stirring up discontent – or even rebellion. In Fayke Newes, historian and international journalist Derek Taylor tracks this long and bloody fight between the press and those in power, through the lives of the men and women who got caught up in the battle. On a journey through the centuries, we criss-cross the Atlantic between Britain and America and discover that neither governments nor journalists have always told the truth.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 505

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To Terry Lloyd of ITNMiguel Gil and Myles Tierney of APTNand all those who’ve lost their lives whilebringing us the news.

By the same author:

A Horse in the BathroomMagna Carta in 20 PlacesWho do the English Think They Are?

Cover Illustration © Adrian Teale

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Derek J. Taylor, 2018

The right of Derek J. Taylor to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8947 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

____________________________________________________

1 The Tudors. Traitors and Heretics

2 Civil War and Oliver Cromwell. The Poisoner of the People

3 John Wilkes. The Terror of all Bad Ministers

4 The American Revolution. Forge of Sedition

5 The Political Cartoon. Poking Fun

6 Nineteenth-Century Radicals. Guerrilla Journalism

7 The Crimean War. That Miserable Scribbler

8 The American Civil War. Wild Ravings

9 Suffragettes. The Truth for a Penny

10 The First World War. A Few Writing Chappies

11 The Press Barons. Mad, Bad and Dangerous

12 The Second World War. Bloody Marvellous!

13 TV News. The Idiot’s Lantern

14 The Soviet Union. Scruffy, Dog-Eared and Undaunted

15 Vietnam. Bang-Bang and Body Bags

16 Watergate. Deep Throat and Dirty Tricks

17 The Falklands. A Quick Win (for the Mighty)

18 Blair and Iraq. The Dodgy Spinners

19 The Social Media Revolution. Trump, Tweets and Fake News

20 The Future. Wobbling On

Acknowledgements

1

THE TUDORS

____________________________________________________

Traitors and Heretics

God hath opened the Press to preachwhose voice the Pope is not able to stopwith all the power of his triple crown.

John Foxe (1516/17–1587)

Around Eastertime in the year 1525, during the reign of Henry VIII, in the village of Aldington, 65 miles south-east of London, a young servant named Elizabeth Barton suffered a sudden seizure. She collapsed, lost consciousness, her body stiffened and then began a violent jerking. It was reported that while in this state, she spoke about the nature of heaven, hell and purgatory, and correctly foretold the death of a child she’d met. When she awoke, she remained very ill. In the sixteenth century, prolonged sickness usually ended only one way. But Elizabeth didn’t die. Not yet.

Uttering religious prophesies was a dangerous thing to do in the reign of Henry VIII. It could mean you were a heretic and might have to be burned at the stake. So, an episcopal commission was set up to investigate, headed by a learned friar named Dr Edward Bocking. He cleared Elizabeth of any heresy. But Bocking himself had some views that were controversial in England of the 1520s, and he now realised that he could use Elizabeth Barton to help him convert others to his own beliefs.

An early nineteenth-century representation of Elizabeth Barton in a seizure. Her elaborate clothing is a fanciful idea – she was a servant girl. It’s not recorded which of the men is Edward Bocking, although the shifty-looking one keeping a written record is the most likely candidate.

That autumn, Bocking arranged for the still sick young woman to appear before a large crowd at the nearby Chapel of Our Lady in the hamlet of Court-at-Street. There she spoke in a mysterious voice, declaring to the people that she’d made a promise to God during a vision she’d experienced at the time of her seizure. After that, she stood up and – miraculously, it was believed – was cured. Elizabeth then entered the Convent of St Sepulchre in Canterbury and became a nun, with Bocking acting as her advisor, or – as her detractors said later – her ‘ghostly father’.

Elizabeth Barton now became a pawn in a momentous and dangerous national and international contest between the king and the pope. Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon had become a disappointment to him. After two stillbirths, two miscarriages and two deaths in infancy, Catherine finally produced a baby that survived in 1516. But it was a girl, christened Mary – and daughters were risky. Queens were more likely to be overthrown.

Henry, who’d already fathered an illegitimate son, concluded that the marriage was the problem. It had been cursed by God. And he could see another – more attractive – way forward. He’d fallen in love with an English commoner’s daughter, Anne Boleyn. He decided he would marry her and she would bear him the longed-for son and heir. But he needed to get a divorce from Catherine first.

Divorce, in the sense we understand it, was impossible in the sixteenth century. Legal separation could be achieved only by the pope’s ruling. So, the king’s representatives would have to negotiate a deal with Pope Clement VII.

There was opposition in the country from conservative Catholics to the king’s planned marriage, and one of the opponents was Dr Bocking, Elizabeth’s ‘ghostly father’. By 1528 Bocking had the young nun firmly under his influence, and he managed somehow to get her close enough to the king to confront him face to face. She told His Royal Majesty to burn English translations of the Bible and to remain faithful to the pope and all he represented. She then warned the king that if he married Anne Boleyn, he would die within a month and that within six months the people would be struck down by a great plague. Henry was disturbed by her prophesies and ordered that she be kept under observation. She wasn’t punished, however – something that would soon change as her fame as a holy prophetess spread.

By 1533, political events were moving fast. In January that year, Henry lost patience with the papal negotiations, and he married Anne. Now it was necessary to pass laws which would justify Henry’s marriage. And in rapid succession, Acts of Parliament removed the English Church from the pope’s jurisdiction and made Henry its head instead. Other acts declared his marriage to Catherine void, and his offspring by Anne to be his legitimate successors.

The king’s enemies were enraged, and royal advisors identified a conspiracy to overthrow him, with Elizabeth Barton, the ‘Nun of Kent’, its chief inspiration. It was at this point that printed books and pamphlets began to appear on the streets of London, and beyond, which told of the Nun of Kent’s miraculous cure and the revelations she’d uttered, revelations that made difficult reading for Henry and his courtiers.

Henry now came to the view that Elizabeth’s words, as reported in print, were heretical and treasonous – the two, amid the politico-religious dramas of Henry VIII’s reign, wrapped up in each other. She was guilty of heresy because, according to the books being circulated, she’d delivered a dead man from the terrors of hell, companies of angels and martyrs had paid homage to her, the Devil himself had come ‘like a jolly gallant’ to woo her to be his wife, and she’d been sent a letter from heaven by Mary Magdalen.

The treasonous element of the nun’s words was even more dangerous. Her prophesy that the king would die one month after marrying Anne Boleyn had turned out not to be true, and Elizabeth Barton’s followers were now claiming this meant Henry was no longer a monarch in the eyes of God, and that he’d die a ‘villain’s death’.

The king’s advisors condemned these claims in words that might have come straight out of Donald Trump’s White House. The prophesies were ‘false fables and tales’, said Henry VIII’s men. And a 1533 Act of Parliament claimed that the nun’s reputation had been built up in order to put the king in the ‘evil opinion of his people’. The treasonous and heretical printed works were to be used, said the official account, in sermons to be preached throughout England on a signal from the nun, in order to put the king, ‘not only in peril of his life but also in the jeopardy, loss and deprivation of his crown and dignity royal’. The problem for the government was made far worse because these books and pamphlets were becoming – by sixteenth-century standards – bestsellers.

✳ ✳ ✳

And so it was that a war began. Not a conventional war, with armies fighting in the field, but a war of words. Whoever said ‘The pen is mightier than the sword’ was wrong. If you write a letter and send it to a friend who reads it and then puts it in a drawer, there’s little power in it. The old adage should have said, ‘The press is mightier than the sword’. Print lots of copies of what you wrote and distribute them, and then your words can reach a multitude of people, prompt debates, cast doubts, make converts, even maybe stir up rebellion.

And this war didn’t die with Henry VIII. It’s been fought, century in and century out, ever after. Not over the same ground, of course – that’s changed countless times according to the great issues of the day and how the government has dealt with them – but from 1533 onwards, those in power have always had to worry about ‘the press’ (what would soon be newspapers, and then, nearer our own time, would expand to include broadcasting and the Internet, all nowadays under the label ‘the media’). It’s a term that’s come to mean the people who control and use it, as much as the technology itself. At stake in this war has always been a prize more valuable than any land won by force of arms. It’s a war to win possession of the minds of the people. And that threatens the power of those at the top.

Johannes Gutenberg

The technology that triggered this war – the printing press – had been around for a century before the anti-government books and pamphlets appeared in Henry VIII’s day, and in its first decades it had been used for largely peaceful purposes. It was born sometime around 1439, when a German goldsmith, named Johannes Gutenberg, realised there might be a way of making hundreds – if not thousands – of copies of a handwritten page. This was a leap of imagination in an age when the only way of reproducing such a document was by laboriously copying it out again and again with quill and ink, or possibly by making the odd smudgy re-version of an illustration with a primitive carved stamp. Mass production was out of the question – until Johannes Gutenberg had an idea.

Gutenberg, like all talented inventers, built on existing technologies but with the tweaks, modifications and combinations of mechanisms that can only come from the mind of a genius. In his workshop in Mainz, he took a screw press, a device which had been used since Roman times to squeeze olives into oil and grapes into the makings of wine, and he added to it ‘movable type’. That is, small metal blocks with the raised, reverse shape of a letter on one side. He didn’t invent movable type – it had been around, though not much used, for at least 200 years – but he did make his type from a special hardwearing alloy, and at the same time he devised a mould that could mass-produce the metal letters in the kinds of numbers needed for a document that might have hundreds of pages.

Replica of a Gutenberg Printing Press from around 1450 on display at the International Printing Museum in Southern California. The massive frame was needed to withstand the force of the tightening screw as it pressed the paper onto the inked type.

Now, in Gutenberg’s press, each page was separately set, with the letters held firmly in a tray known as a ‘coffin’, before ink – another first for Gutenberg, it was oil-based – was applied with balls of sheep’s wool. A sheet of paper was then fixed onto a flat surface, and the coffin – with the inked letters face down – was placed on top. This was pushed hard onto the paper by means of the screw press. The result was text printed on paper.

Over the next sixty years, Gutenberg’s invention slowly caught on across Europe, and by the end of the fifteenth century was turning out pamphlets and books in 110 cities. It’s been estimated that 20 million volumes, of various lengths, had by this stage been pressed and bound.

Although there was a market for ballads and romances, it was mainly religious works that were printed. In the 1450s, Gutenberg himself had produced around 180 copies of the Bible in Latin, a work that still bears his name.

In London, because the Church was the biggest customer of the printing business, the presses were set up in workshops around St Paul’s Cathedral, and that’s where the presses were still to be found until the 1980s. If you stand today on Ludgate Hill with the great west door of the cathedral behind you, and look ahead, you can see down the length of Fleet Street, for centuries a synonym for the national newspaper industry in Britain.

Gutenberg could not have guessed that the device he’d created in his workshop would change the world forever. The so-called digital revolution of our own age can’t compete with the invention of the Gutenberg press. In effect, he’d invented mass communication.

It’s almost impossible for us today to imagine living in the world before Gutenberg when, for 99 per cent of us, 99 per cent of the time, all we would have known would be either happenings in our own village or town, or occasionally some oft-repeated – and undoubtedly oft-embellished – rumour of great events far away. And because knowledge is power, the printing press would, step by step, change forever the structure of society. It started to break the hold of the elite on learning and education, and so it boosted the rise of middle-class merchants and tradespeople. There was also an increase in the number of those who could read during the first half of the sixteenth century, encouraged by the availability of printed books.

But literacy levels were only part of the reason for the growing popularity of whatever the presses could produce. There’d always been a strong oral tradition throughout the Middle Ages, with storytelling around the fire being the main way that legends and traditions were passed from generation to generation. However, word of mouth didn’t now die out. In fact, it gave more power to the press, because those who could read often did so out loud, telling friends, family and neighbours what was in the latest book or pamphlet.

This newfound ability to spread information relatively rapidly made possible mass movements in politics and religion. Ideas could more easily cross borders. And all of this would soon be a terrible threat to the most powerful institutions, the Church and the monarchy. Heresy, treason and sedition could suddenly catch on right across the country.

In the early sixteenth century, Europe was becoming increasingly split between those who followed traditional religious practices defined by the pope in Rome, and newcomers who chose the beliefs of Martin Luther and the Protestants. The press was the means of disseminating these new ideas.

The first attempt in England to stop them flooding in from across the Channel had come in May 1521, when a pile of Lutheran volumes, considered heretical, was burned outside St Paul’s. But smuggling continued, and the Bishop of Norwich, wringing his hands in despair, declared, ‘It passeth my power or that of any spiritual man to hinder it now, and if this continue much longer it will undo us all’.

Henry VIII would have sympathised with the bishop’s frustration. As he was about to discover – like many a king, president and prime minister who came after him – there was no easy way to stop the onslaught from ‘the press’.

✳ ✳ ✳

Henry tried. In July 1533, under fire from these treasonous and heretical printed volumes, he fought back on two fronts. He attacked the source of the ‘false tales and fables’, while at the same time trying to suppress the mechanism that had published them.

The source was Elizabeth Barton, and the king now ordered his secretary, Thomas Cromwell, and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer to take action against her. Royal agents entered the Convent of St Sepulchre in Canterbury, seized the nun, and brought her before the archbishop for questioning. Cranmer adopted a soft, manipulative approach in his interrogation, pretending he believed her every word – and it paid off. He won her confidence, and by November she’d confessed to a conspiracy against the king. Names were named. Arrests were made.

Those accused were thrown into the Tower of London, and on 23 November they were subjected to a staged public humiliation. While they stood, heads bowed, on a scaffold before a huge crowd outside St Paul’s Cathedral, the Abbot of Hyde read out extracts from a printed book of Elizabeth Barton’s revelations. He reviled both them and the nun herself. She’d lived it up while in the convent to become ‘fat and ruddy’, said the abbott – and what’s more she’d had sex with Bocking the night before her revelations. However, no evidence was produced to support these allegations.

But all this was not enough. The king wanted the conspirators condemned in the eyes of the law as traitors and heretics. Henry and his secretary Cromwell, however, were worried that a jury might let them off. So, Parliament was persuaded to pass an Act authorising punishment without trial.

On 20 April 1534, Elizabeth Barton, her ghostly father, Bocking, and four other priests were transported in shackles on an open cart across London to the west and over the fields to the village of Tyburn – today this is where Marble Arch stands at the end of Oxford Street. In front of another huge crowd, the five of them were hanged, then cut down and decapitated. Elizabeth’s head was put on a spike at London Bridge. It’s believed she was the only woman ever subjected to this dishonour.

Meanwhile, Thomas Cromwell had his spies out. A compilation of some of the Barton books and pamphlets, called The Nun’s Book, was now being circulated. Henry and Cromwell considered it inflammatory and dangerous. Cromwell tracked down the printer who, under pressure, confessed to having 200 copies of the book and revealed that Bocking was his paymaster and had a further 500 copies. All 700 were seized and publicly burned. At the same time, Cromwell got hold of other treasonous books and pamphlets, which were also thrown on a bonfire.

And in the same month that Elizabeth Barton was hanged, Parliament – loyal to the king – was persuaded to pass a law that made it high treason to print and publish anything that argued against Henry’s marriage to Anne Boleyn, and treason was punishable by death.

But the burning of a few objectionable volumes – or, indeed, of women and men – no longer seemed to have the power to deter others. Those who might have been scared off in a previous age, now – because of the printing revolution – could feel they were not alone, but part of something bigger. Cromwell’s actions caused little more than a stutter in the torrent of words, hostile to the king and his actions, pouring off the printing presses at home and abroad.

Thomas Cromwell, however, had learned one very valuable lesson. He realised that the weapon wielded by the king’s enemies could be turned back on them. The press could be just as powerful in the hands of the government. He recognised that if the plot by the nun, Bocking and their accomplices could be exposed to the population at large as evil, then that would boost popular support for the king. So, Cromwell, through his contacts in London’s burgeoning printing industry, encouraged and patronised writers and printers to publish works not only to destroy the reputation of Elizabeth Barton and the other traitors, but also to promote the benefits of the new independence from Rome of the Crown and England’s religion.

A chance to use the new weapon at a time of crisis came two years later. A dangerous rebellion against the king broke out in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire. Cromwell persuaded the king to have a pamphlet printed that answered, point by point, the rebels’ complaints about Henry’s break with Rome and his dissolution of the monasteries. It was distributed in the rebel areas.

We’ll see this happen often on our journey through the centuries – the ‘mighty’ hijacking the media. And they’ll do it in many ways – some subtle and some crude. And what’s more, sometimes those who control or work in the media will help the mighty do it.

✳ ✳ ✳

Henry VIII’s two successors on the throne, however, had no Cromwells at their sides, and the lesson of using the press to promote the royalist cause, for the moment, was forgotten. After the old king’s death in 1547, his Catholicism without the pope vanished during the two short reigns of Edward VI and Mary – the first an evangelical Protestant, the second the complete opposite, an uncompromising supporter of the papacy. Although Edward and Mary had little in common when they knelt to pray, they faced similar problems from their enemies, and both failed in pretty much an identical fashion. Neither were press savvy, and government use of printing for propaganda purposes during their reigns was almost non-existent.

Meanwhile, more and more material, threatening to those in power, was being printed or brought into the country from overseas. Sometimes these printed attacks were carefully argued academic treatises against the Protestantism of Edward or the Catholicism of Mary, but they were also often short pamphlets – relatively cheap to produce and buy – lampooning the personal foibles and beliefs of the monarchs.

Some of the defamatory attacks on Mary and her religion were printed to further a specific conspiracy. And some were part of a general campaign to besmirch her name. The Protestant opponents of Mary seemed more imaginative in their vitriol against her than the Catholics against Edward, and were more effective users of the press. Printed papers often described her as a ‘jezebel’, which meant, to those who knew their Old Testament, a false prophetess, a whore and – in a spirit of hope – someone who was killed when her courtiers threw her out of a window, her corpse then eaten by stray dogs. And the most celebrated assault came from the Scottish Protestant Reformer, John Knox, in his book on The Monstrous Regiment of Women, which described Mary as a ‘horrible monster’ who ‘compelled Englishmen to bow their necks under the yoke of Satan’.

Both Edward and Mary and their advisors reacted in a similar way to such attacks against them. They became more and more frenetic in their attempts to stamp out the hostile press. In 1549, a proclamation in Edward’s name decreed that nothing – it’s worth stressing – nothing at all, written in the English language could be printed or sold unless it had first been approved by a member of the Privy Council. An ambitious, not to say unachievable, aim.

Mary was extra vulnerable because of her marriage to the King of Spain. She could see that Edward’s proclamation hadn’t worked, and ‘very lewd and rude songs against the Mass, the Church and the Sovereigns’ continued to spread throughout the kingdom. So, a new Act was passed with the stated aim of quashing those ‘diverse heinous, seditious and slanderous writings, rhymes, ballads, letters, papers and books’ which were stirring up discord.

Now if you were found guilty you would be pilloried, that is, locked in the stocks or a similar device as a humiliation, where any idle or incensed citizen could throw eggs or stones at you. You’d then have your ears cut off, unless you could afford to pay the mountainous sum of £100. The law further said that if the crime was an attack in print against the queen or her Spanish husband, then the penalty was having your right hand chopped off. When these threats failed to have much effect, it was decreed in 1558 that possession of any heretical or treasonable book, whether printed in England or imported, would be punishable by death.

The ferocity of these penalties was a sign of desperation, a confession of failure by the authorities. In fact, no record of a single successful prosecution has been traced. Not because seditious and blasphemous works weren’t out there – we know they were – but because so few journalists, publishers and printers were caught and convicted. One of the main problems was that enforcement of these laws depended on local Justices of the Peace, and they often let their own personal sympathies override their duty to uphold the law of the land. The state was discovering that an effective, anti-democratic dictatorship (as we might see it) needs a widespread efficient bureaucracy to impose its will on the people, especially in an age when uncontrolled mass communication can spread discontent relatively fast and far. Tudor England had no such bureaucracy.

✳ ✳ ✳

In 1558, Catholic Mary died and was succeeded by her Protestant half-sister, Elizabeth.

In the popular imagination today, there’s a stark contrast between the two queens. Mary, still remembered as ‘Bloody Mary’, for the way she presided over the brutal execution of hundreds of Protestant heretics. Elizabeth, ‘Gloriana’, for the way she defended the nation against the Spanish and brought peace and prosperity to a previously divided people. The truth is, of course, much more complicated than that.

For a start, the executions for heresy didn’t stop under Elizabeth – 190 priests and lay Catholics were burned at the stake during her reign, and torture was more common under her than at any time in English history. But what’s revealing is why this image of the bad queen and the good queen arose in the first place and then stuck in the popular mind for 400 years.

In part, it’s because Elizabeth herself was cleverer than her half-sister. Elizabeth knew far better than Mary how to play the politics game. She knew when to compromise, and when to show sympathy for those she didn’t agree with. And these tactics benefitted her image. But there was something more – and that was a favourable press. Protestant authors, now released from the oppression of Mary’s reign and always more adept than their Catholic opponents at using the power of printed propaganda, set to with a will.

The most effective of them all was John Foxe, an academic who rejoiced at the accession of a queen who would defend the Protestant cause. His Book of Martyrs became a classic. It gave a flame-by-flame, dying-scream-by-dying-scream account of how the most famous bishops, abbots and lay Protestants had been burned as heretics during Mary’s reign. He it was who coined the nickname that’s lived on – ‘Bloody Mary’. His writing is highly biased. He made no pretence at objective journalism. He didn’t need to. It was a concept unknown in the sixteenth century. Foxe dedicated his book to Queen Elizabeth, and she in turn recognised its huge value to the nation’s Protestant faith and her role as its defender. She commanded a copy of Foxe’s Martyrs be placed in every church in the land. Now, that was a real contrast with her sister. Elizabeth, unlike Mary, knew the power of the press.

So, did that mean that she was also more successful at suppressing opposition pamphlets and books? Here the answer is not so clear. She certainly tried. The threat to her crown was very real. In 1570, Pope Pius V gave clear and open instructions to those of Elizabeth’s subjects who still practised the Catholic faith. He absolved them of their loyalty to her. The government now feared that the sprinkling of Catholic citizens left in the country was a fifth column, ready and waiting to assist any attempted invasion by a foreign Catholic army. And so, the following year, Elizabeth made it treason to import, publish or put into effect any printed account of the pope’s words, or anything asserting ‘that the Queen is a heretic, schismatic, tyrant, infidel or a usurper’.

Archbishop Cranmer being burned at the stake, from Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. Elizabeth I learned that she could use the press to hit back at her opponents, and she decreed that a copy of Foxe’s work, with its graphic illustrations of Catholic brutality, should be placed in every church in the land.

Did this deter rebels from printing and circulating treasonable or heretical books and pamphlets? It’s impossible to judge how many people during Elizabeth’s reign, who might otherwise have got involved with publishing rebellious works, decided against it for fear of getting caught and punished. But historians today do think that, despite having her own Cromwells around her – Sir Francis Walsingham and William Cecil with their network of spies and informers – she may not have done much better than Edward or Mary in controlling the hostile press.

Certainly, one of the most famous cases during Elizabeth’s reign was hardly a massive victory for the government. The accused at its centre was more loyal dunderhead than dangerous insurgent. In 1579, the queen was contemplating marriage to the Duke of Anjou, a Catholic, and brother of the King of France. It never came to anything, but while it was on the cards, a puritan lawyer called John Stubbs put his objections into a pamphlet which he had printed and distributed. It went by the explicit – if not catchy – title of The Discovery of a Gaping Gulf whereunto England is like to be swallowed by another French Marriage, if the Lord forbid not the banns, by letting her Majesty see the sin and punishment thereof.

Stubbs described the proposed wedding as ‘an uneven yoking of the clean ox to the unclean ass’. Clean or not, ‘ox’ was hardly the most diplomatic name for your monarch. And he added that the union would draw the wrath of God down on England, and leave ‘the English people pressed down with the heavy loins of a worse people and beaten as with scorpions by a more vile nation’.

He was simply being a good, patriotic Englishman, he argued. It was a sign of the government’s nervousness that Stubbs, his printer and publisher were all seized and put on trial. Although Stubbs protested his loyalty to the Crown, he was found guilty of ‘seditious writing’, and sentenced to have his right hand chopped off. Elizabeth herself had to be talked out of ordering the death penalty for him.

In the moment before he received his lesser punishment, Stubbs had sufficient equilibrium to utter what may have been intended as a joke, ‘Pray for me, now my calamity is at hand’ – a bad pun can be forgiven in the circumstances. Then, once his right hand had been removed by a meat cleaver driven through the wrist with a mallet, he raised his hat – with his left hand – and declared, ‘God Save the Queen!’, then fainted.

A much more serious threat than John Stubbs came from the Jesuits, who were becoming increasingly active in the country. They made good use of the printing press to spread their beliefs. Their most celebrated member, Edmund Campion, worked underground to promote the Roman Catholic ministry. He was arrested by priest-hunters. Although he protested, ‘We travelled only for souls. We touched neither state nor policy’, he was still considered too dangerous – as were many other Jesuits – and he was convicted of high treason, before being hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn.

Nevertheless, the tide of Catholic printing was not turned back, and Elizabeth faced several serious Catholic rebellions and plots during her reign. Her ability to defeat them and stay on the throne is more down to the fact that Catholics were finding it difficult now to raise widespread support, rather than because of any effective control of the hostile press.

✳ ✳ ✳

But the battle lines in the war between the press and those in power had been drawn, and the first volleys had been fired. Once the Nun of Kent’s prophesies had been set in type, inked and pressed onto paper, nothing in politics would ever be the same again.

Following Queen Elizabeth’s death in 1603, those at the top could not now ignore the threat from this monstrous machine. The press – the technology and those who wrote what it published – could loosen their grip on power. As we’ll discover on our journey through the centuries, all rulers, everywhere in the world – one way or another – would have to deal with that threat.

The advantage – as in most wars – would often shift from one side to the other. Sometimes, monarchs, elected politicians and military leaders in wartime would gain the upper hand by banning, threatening, bribing, cajoling, discrediting, taxing or even imprisoning or executing those who might publish things they didn’t like. Or they’d simply censor what the people could be told. Then the mighty would be free to seize control of the media and use it to push their own propaganda on the masses.

Throughout this long war, it would be the job of journalists to resist, and to report with accuracy what they found out. As we’ll soon see, they’d sometimes fail. Truth wouldn’t always be their weapon of choice. But many times, it would, and then through the determination and bravery of individual editors and reporters, the truth would flash home like a sword in the sunshine, targeting the misdeeds, the mistakes and the secrets of the mighty.

And over four centuries, as society itself was to change, so would the nature of this war. Developments in technology, in beliefs about democracy and freedom, and in the very definition of journalism itself, as well as the rise and fall of political leaders, the outbreak of rebellion and wars, the need to make a profit, would all play their part in pushing the battle lines this way and that. But through all this turmoil and sometimes bloodshed, one thing wouldn’t change. The media and the mighty will always be natural enemies.

It’s going to be a long, messy, at times bloody, conflict. And that – with all its many battles over the centuries – is what we’re now going to investigate. We shall criss-cross the Atlantic on our journey between Britain and America, even visiting the Soviet Union, and we’ll meet the men and women caught up in the fighting. And as we reach the twenty-first century, we’ll face some tricky questions. Is the world today – when fake news, Donald Trump and social media dominate the fight – experiencing something new in the media–mighty conflict? Or is it the same old war, the same old opponents, fighting for the same causes as ever, but just with different weapons?

✳ ✳ ✳

There’s a long road to travel before then, though. So let’s return to what happened after the death of Queen Elizabeth I. The next eighty years were to be arguably the most tumultuous in English history, marked by civil war and the execution of a king, followed by a military dictatorship. It would all be ammunition for the printing press, which would be as powerful a weapon as any musket, sword or executioner’s axe.

One short, stocky man with an odd name would know better than anyone how to wield that weapon, and – as we’ll discover next – how to persuade whoever happened to be in power to pay him to be their journalist.

2

CIVIL WAR ANDOLIVER CROMWELL

____________________________________________________

The Poisoner of the People

The pen is a virgin, the printing press a whore.

William Cavendish (1592–1676)

On 20 August 1620, in the market town of Burford in Oxfordshire, the daughter of the landlord of the George Inn, Margery Nedham, gave birth to a boy. Though he looked a healthy baby, the family wanted to take no risks. In the seventeenth century, many an infant died in those first days, and it was best to get them baptised quickly. So the next day, the family and their friends processed down the hill to the Church of St John the Baptist. Burford was a wealthy place, which had made its money from the wool trade, the profits of which had helped to build its magnificent cathedral-sized place of worship.

We don’t know whether the mother was recovered enough to be there at the church, but the father – described as a ‘genteel man’ – now stood before the ancient font, and advised the vicar that the child was to be christened ‘Marchamont’, the same as the father himself. Why the Nedhams called their sons such an odd name is a mystery. In fact, Marchamont is so unusual as a Christian name that it doesn’t appear in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, other than in the entry for Marchamont Nedham – this latest addition to the family.

He was going to make his mark on history. His extraordinary career and unpredictable character would take him to the front line of a war of words that would be fought between different sets of governments and rebels over the next sixty years.

Within months of young Marchamont’s birth, his father was dead and his mother remarried, this time to the Vicar of Burford himself, the Reverend Christopher Glynn. Marchamont’s stepfather was also master of the local free grammar school, and he made sure the boy got a thorough education, not only in reading, handwriting, the Bible and a certain amount of Latin, but also in mathematics and the sciences such as magnetism and chemistry. And Marchamont would have had seen something quite new, printed textbooks.

Then, at the age of 14, he went off to Oxford, 20 miles away, as a chorister in the chapel of All Souls’ College, while he continued his studies there. At the age of 17, he graduated with a bachelor’s degree – this was the normal age to get your BA in the seventeenth century. After that, he went off to London where he worked as a junior master at the Merchant Tailor’s School for four years. At this point, he seems to have got restless. He didn’t know what he wanted to do with his life. He briefly studied medicine, and worked as an under-clerk to the lawyers at Gray’s Inn.

At the age of 23, Marchamont Nedham got his first big break. He was invited to become chief writer of a publication called Mercurius Britannicus. This was one of a new breed of printing press productions, the periodical newsbook. It was the forerunner of today’s newspaper, though it looked more like a small magazine. The key difference from the one-off books and pamphlets we saw during Tudor times, was that newsbooks came out in regular editions, usually once a week, which meant they could build up a readership.

What young Marchamont Nedham had done to win this position, or who he’d met that had swung it for him, we can only guess. Those who’ve examined in detail the writing style of the various editions of Mercurius Britannicus at this time, can’t detect any change with Nedham’s appointment, which has led to the theory that maybe he was already writing for the publication before, perhaps on a trial basis.

But if we’re looking for an explanation for why, around 1643, Marchamont Nedham switched careers to become a journalist, we need look no further than what was happening in the country. These were turbulent days in England, some of the most violent and uncertain in the country’s history. King Charles I, who’d come to the throne in 1625, was trying to put back the clock. He believed kings were answerable to God alone, so ignoring the past 350 years of Parliament’s rising power. And what’s more, he was suspected of nurturing an ambition to return England to Roman Catholicism.

The country’s religious divisions were pushed to extremes under Charles. On one side, the Presbyterians and Puritans who sought to exercise their influence through Parliament. On the other, the High Church Anglicans who backed the king. Tension between them was such that it would take only the merest jolt to turn peaceful disagreement into violent rage. And jolt it Charles did.

On 4 January 1642, stung by his openly Catholic wife’s accusation that he was a coward, the king marched into the Palace of Westminster with 200 armed courtiers to arrest one peer and five MPs suspected of plotting against him. But it was a botched job. The six men escaped, and Parliament pronounced the king a ‘public enemy to the commonwealth’. It was the start of the most bloody and divisive civil war in England’s history. And as armies marched and battles were fought on home territory, there was an unprecedented demand among the populace for news of what was happening and opinions as to what to make of them.

Mercurius Aulicus, a newsbook supporting the royalist cause, was printed in Oxford and Bristol during the Civil War. This issue from April 1645 begins, ‘The rebels, this Easter, have excommunicated themselves...’ The parliamentarians hit back with Mercurius Britannicus, whose chief writer was Marchamont Nedham.

Exciting times for a 23-year-old, trying to find his place in the world. The war was getting into full swing as Marchamont Nedham was appointed chief writer at Mercurius Britannicus. Britannicus was firmly on Parliament’s side in the conflict. It had been founded to counter the propaganda being pedalled by a Royalist newsbook called Mercurius Aulicus. King Charles, earlier in his reign, had refused to indulge in anything so demeaning as communicating with his subjects – such action hardly befitted a king with a divine right to rule. And he’d tried to impose the same restraint on his opponents by banning the printing of domestic news. But that prohibition had collapsed by 1641, when Charles lost control of Parliament. The many Presbyterian-owned printing presses immediately started churning out an estimated twenty different newsbooks, most with a pro-Parliament and anti-Royalist bias. Even Charles now realised he had no alternative. He’d have to do the same and swallow his I-only-talk-to-God principles.

And that was the start of Mercurius Aulicus. It specialised in systematic smearing of opponents and scandalous news stories. We can get a flavour of its style from this entry in the edition of 17 December 1643. In it, Aulicus, after reminding its readers that the Parliamentary rebels were always boasting about how they held Sundays sacred, went on – with lip-smacking irony – to describe what one Parliamentary prisoner had got up to in Shrewsbury:

On Sunday last, while His Majesty’s forces were at church, one of the prisoners was missed by his keeper, who searching for him and looking through a cranny in the stable, he saw a ladder erected and the holy rebel committing buggery on the keeper’s own mare.

That’s what Britannicus aimed to combat. And Marchamont Nedham’s writing style must have been what appealed to its owners. One contemporary critic of his said Nedham was ‘transcendently gifted in opprobrious and treasonable droll’. In other words, he could be witty and vicious in his seditious attacks on the country’s rulers.

One of his first targets, for instance, was the Church hierarchy. He wrote:

Bishops are the big-bellies, the red nose tribe of priests [who] preach and exercise nothing else but broad-sword divinity to hack and hew down the main pillars of reformation and liberty.

In these early days, he held off from any full-on assault against the king, instead complaining in a roundabout way of it being ‘unlawful to speak plainly to the king in his ways’.

In 1645, he managed to get hold of Charles’ private papers which had fallen into enemy hands after the Battle of Naseby. He published them, adding satirical notes of his own. And then in a subsequent issue, he hardened his line against the king with personal insults and a spot of fake news. Nedham began by putting out a mock appeal for anyone to come forward who’d spotted the king anywhere, and he mentioned in passing that they’d know him by his stammer:

If any man can bring any tale or tiding of a wilful king, which hath gone astray these four years from his Parliament with a guilty conscience, bloody hands, a heart full of broken vows and protestations – if these marks be not sufficient there is another in the mouth, for bid him speak and you will soon know him – then give notice to Britannicus and you shall be well paid for your pains … As sure as can be, King Charles is dead, and yet we never heard of it: I wonder we have not his funeral sermon in print here.

By May 1646, Nedham was writing an editorial describing the king as a tyrant, and suggesting he was trying to overthrow Parliament by setting the Scots and English against one another. This time, he’d gone too far. The Royalist authorities shut down Mercurius Britannicus, arrested Nedham and threw him into London’s Fleet Prison. He got himself released two weeks later by agreeing to desist from publishing anything further, and he paid a £200 surety against his future good behaviour. However, there’s some evidence that – despite this – he just carried on writing under a false name, while he supported himself by practising as a physician.

✳ ✳ ✳

Over the next few years, several of these ‘Mercuries’ – all with high-sounding Latin names, some pro-Parliament, some for the king – sprang into being, and often died just as suddenly. Although it’s been estimated that only around 30 per cent of England’s population could read at this time, that figure jumped to 70–80 per cent in London. The public demand for news and comment on current events seemed insatiable, and in 1641 the government was forced to lift the ban on printing domestic news. Within four years, over 700 different newsbooks and other news-sheets were in circulation. Two years later, Parliament decided that all this publishing was getting out of hand, and introduced a system of licensing. Printers and writers who flouted the new rules could be fined, whipped or imprisoned and their presses confiscated.

It was at this moment that Marchamont Nedham pulled off his next coup. He somehow inveigled his way into Hampton Court Palace, and got himself introduced to the king. He knelt before the monarch, kissed his hand and begged the royal forgiveness, which – despite all the very rude and treasonable things he’d written about Charles – was ‘readily granted’. Whether or not he offered at this meeting to commit his talents to the Royalist cause, we don’t know, but that’s precisely what he did. He began to publish, and of course to write for, a new Mercury, Mercurius Pragmaticus. And he packed its pages with commentaries on the events of the day, as well as witty and vitriolic attacks, now against the king’s enemies. Oliver Cromwell, for instance, was mocked as ‘Copper-Nose’, ‘Nose Almighty’ and ‘The Town-bull of Ely’.

So instantly successful was Pragmaticus that many others counterfeited it. No fewer than seventeen other Pragmaticuses regularly appeared on the streets, each pretending to be the real thing. Some just wanted to make money by sneaking a share of its market, while others aimed to blacken the reputation of the real Pragmaticus by printing outrageous libels in its name.

But it was Nedham’s own enthusiasm for journalism that now got him into trouble. He started to include in the real Pragmaticus accounts of proceedings in Parliament. Parliamentarians didn’t like that. They saw it as highly dangerous, because debate, disagreement and quotes out of context could be used by Royalists to discredit them. So, within a month of its first appearance, the printer of Pragmaticus, one Richard Lownes, was thrown into jail, and Nedham himself fled London.

For a while, Nedham managed to keep publishing and to stay one step ahead of the Parliamentary spies. But then in January 1649, he lost his royal patron. In one of the most momentous events in English history, King Charles I was found guilty in Parliament of ‘being a tyrant, traitor and murderer, and a public and implacable enemy to the Commonwealth of England’, and had been executed. By June that year, Nedham’s luck ran out. He was arrested, and he found himself back in prison.

But then there was a remarkable intervention by no less an important Parliamentary personage than the Speaker of the House of Commons, William Lenthall. Nedham’s talents were still in demand. Master Lenthall pleaded his case and won him a pardon, on condition that Nedham switch sides a second time. England was now a republic, and its leaders in Parliament reckoned that Nedham had just the skills to persuade the people of its righteousness.

And so, on 8 May 1650, just released from jail, Nedham published a pamphlet entitled The Case of the Commonwealth of England stated … with a Discourse of the Excellency of a Free State above a Kingly Government. In the prologue, Nedham felt he had to defend his latest U-turn. He told his readers:

Perhaps thou art of an opinion contrary to what is here written; I confess that for a time I myself was so too, till some causes made me reflect with an impartial eye upon the affairs of the new government.

Oliver Cromwell: Marchamont Nedham insulted him as ‘Nose Almighty,’ and ‘The Town-bull of Ely.’ When Cromwell became Lord Protector, he forgave Nedham, and employed him as his own press propagandist.

And Nedham was not only free to practise his profession again, he also received a more tangible reward. The Council of State voted him a one-off fee of £50 and a pension of £100 a year ‘whereby he may be enabled to subsist while he endeavours the service of the Commonwealth’. Nedham set about his new commission, and on 13 June 1650 he brought out the first edition of yet another Mercury, Mercurius Politicus. It opened with a heated attack on the institution of monarchy and ended with a ‘Hosanna to Oliver Cromwell’.

Cromwell, now hailed as the successful Civil War general, was fast rising to the top. And in 1653, he became ruler of England, not as a king but with the title Lord Protector. In effect, it was a military dictatorship. ‘Government,’ said Cromwell, ‘is for the people’s good, not what pleases them.’ But he and his army grandees were practical men, and they could see that opposition was less likely if the people were also told what was good for them.

Cromwell recognised the usefulness of the printed word. So it was that this otherwise ruthless autocrat turned to the same man who’d insulted him as ‘Nose Almighty’ and the ‘Town-bull of Ely’. In fact, Cromwell was so impressed by what he read in Politicus that he not only overlooked the old smears he’d suffered, but he awarded Nedham a £50 a year pension. And what’s more, he granted him a one-off gigantic payment of £500.

Then, in 1655, Mercurius Politicus was adopted as the official mouthpiece of the government, with its editor Marchamont Nedham, in effect, chief propagandist to the Lord Protector. At the same time, the government passed laws subjecting the rest of the press to stringent censorship – nothing was permitted to be published that showed the new regime in a poor light or that could be seen as stirring up revolt. The ban wasn’t totally effective because, by 1655, England’s postal service was delivering mail three times a week, and some of Cromwell’s opponents were taking advantage of it to send out regular anti-government newsletters.

However, Nedham’s Politicus was far and away the front runner in the propaganda race, so Cromwell now heaped even more responsibility on him. Nedham was handed the editorship of another official government newsbook, titled the Public Intelligencer. He was a busy man, with Politicus coming out every Thursday and the Intelligencer each Monday. And he was now becoming a celebrity in his own right, though hardly in a way to be welcomed. He was attracting the personal venom of those outside the ranks of Cromwell’s supporters. An independent-minded preacher called John Goodwin denounced Nedham as having ‘a foul mouth, which Satan hath opened against the truth and mind of God’, and being ‘a person of an infamous and unclean character’.

Nedham’s position was shaky. As it had been with the king before, he was dependent on the fortunes of one man. And when Cromwell died in 1658, and Richard, his weak and ineffective son, took over, Nedham’s detractors felt even more free to gun for him. They accused him of being ‘a lying, railing Rabshakeh’ – an Old Testament character who used promises and lies to try and turn the populace against their ruler – ‘and a defamer of the Lord’s people’. There were increasingly loud demands now for Nedham to be fired from all public employment. But when Parliament was recalled in May 1659, the two houses dithered about what to do with him.

At first, they fired him as editor of the Public Intelligencer. Nedham was unbowed. He started yet another paper, called The Moderate Informer, and published a one-off pamphlet to prove that the whole country, high and low, of every party, would suffer if King Charles II returned from exile and was put back on the throne. Parliament liked that, and so changed its mind and put Nedham back in charge at the Intelligencer. But, the mood of the country at large was shifting. By early 1660 it was becoming clear that popular support was growing to bring back the king. So Parliament – seeing which way the wind was blowing – did another backtrack and stripped Nedham of his editorship of both Politicus and the Intelligencer.

Now Marchamont Nedham was in deep trouble. He’d run out of options, and the Royalists issued a pamphlet of their own which argued that the restoration of the monarchy wouldn’t be complete unless Master Nedham were indicted for treason and hanged. Its writer, Roger L’Estrange, a strong supporter of Charles II, wrote that Nedham had:

with so much malice calumniated his Sovereign, so scurrilously abused the nobility, so impudently blasphemed the Church, and so industriously poisoned the people with dangerous principles, that the Devil himself (the father of lies) … could not have exceeded him.

Nedham knew when to run, and he high-tailed it across the Channel to Holland. Two weeks later, at the end of May 1660, Charles II crossed back the other way and England was a monarchy again.

But Nedham, it seemed, was irrepressible. Within a few months, he’d obtained the new king’s pardon, bought – according to his enemies – with ‘money given to a hungry courtier’, and he too came back from exile. Now, though his writing days weren’t over, he steered clear of politics – for the moment anyway.

For the next few years, he maintained what for him was a low profile. He practised as a doctor, but couldn’t keep away from the printing press. He did a bit of pamphleteering on the side, making rather less controversial points on matters of education mixed with attacks on the College of Physicians. But his political journalism was to make one last big splash.

In 1676, King Charles II – like Charles I and Oliver Cromwell before him – conveniently forgot that Nedham had so attacked and insulted him, and now paid him £500 to publish a tirade against one of his enemies, the Earl of Shaftsbury. Nedham showed that his taste for acid vitriol was far from dulled. The earl, he wrote, was:

… a man of dapper conscience, and dexterity, that can dance through a hoop … a pettifogger of politics, ever ready to shift principles like shirts and quit an unlucky side in a fright at the noise of a new prevailing party … a will-o-the-wisp that uses to lead men out of the way then leaves them at last in a ditch and darkness, and nimbly retreats for self-security.

The irony of this invective is nothing short of delightful. It could be a perfect summary of Marchamont Nedham himself. But the attack on Shaftsbury was to be his swansong. Anthony Wood, an Oxford academic who’d lived through Nedham’s years in the public eye, wrote:

This most seditious, mutable, and railing author died suddenly in the house of one Kidder, in Devereux Court, near Temple Bar, London, in 1678, and was buried on the 29th of November at the upper end of the body of the church of St. Clement’s Danes, near the entrance into the chancel.

Two years later, when the chancel was rebuilt, Nedham’s monument disappeared.

✳ ✳ ✳

Marchamont Nedham has been described as ‘the world’s first great journalist’, though reporters and editors in the twenty-first century might not relish being lumped in with a man whose cynical opportunism meant he was ever ready – in his own words – to ‘shift principles like shirts’. Clearly, though, what you can’t dispute is that he knew what his readers wanted to hear, and he knew how to write it in a way that made them come back for more.

So, was there any consistent guiding light behind his side-switching career? Some historians have argued that he never changed his passionate hatred of ‘priest craft’, in other words, the way that clerics of all churches were hungry for power. The Presbyterians and Catholics, he wrote in 1650, were all the same, and he complained of:

… the popish trick taken up by the Presbyterian priests in drawing all secular affairs within the compass of their spiritual jurisdiction… [bringing] all people into the condition of mere galley slaves while the blind priests sit at the stern and their hackney dependents, the elders, hold an oar in every boat.

Nedham was also a fan of Machiavelli, who most certainly would have approved of his lack of moral scruples when it was expedient to go back on your word and slip over to the other side.

But there was something else going on with Nedham that might strike a chord with the world’s great media owners of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. He was perhaps the earliest exponent of the benefits of a society where you were free to make money, and he acted on it. He was one of the first, if not the first, to introduce paid advertising into journalism, and it made Mercurius Politicus throughout the rule of Oliver Cromwell a profitable, as well as a popular, success. In 1652, he wrote that commercial interest ‘is the true zenith of every state and person … though clothed never so much with the specious disguise of religion, justice and necessity’.

And whatever else we may say about Marchamont Nedham, he did not lack courage. He came very close to being hanged in 1660, and that risk did not go away over the following decade, when others were not so fleet-footed or smooth-tongued as he, as the case of John Twynn showed.

In 1663, Twynn sat in a cell in London’s Newgate Jail awaiting his execution. He’d been involved in publishing an anonymous pamphlet justifying the people’s right to rebel. It was ‘meddlesome stuff’, according to the official state censor. There was no suggestion that Twynn had written the treasonable words himself; he was just the technician who’d set up the press and printed the booklet. The authorities offered him a deal. Reveal the name of the journalist behind it and Twynn would be spared the death penalty.