Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

What makes the English so . . . English? The English are often confused about who they are. They say 'British' when they mean 'English', and 'English' when they should say 'British.' And when England, more than the rest of the UK, voted to leave the EU, polls showed national identity was a big concern. So it's time the English sorted out in their minds what it means to be English. A nation's character is moulded by its history. In Who Do the English Think They Are? historian and journalist Derek J. Taylor travels the length and breadth of the country to find answers. He discovers that the first English came from Germany, and then in the later Middle Ages almost became French. He tracks down the origins of English respect for the rule of law, tolerance and a love of political stability. And, when he reaches Victorian times, he investigates the arrogance and snobbishness that have sometimes blighted English behaviour. Finally, Taylor looks ahead and asks: faced with uncharted waters post-Brexit, what is it in their national character that will help guide the English people now?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 548

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To Maggie, Dan, Jo and Nathan

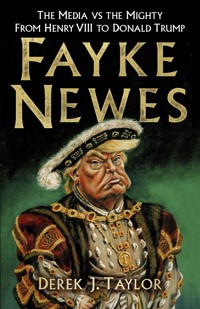

By the same author:

A Horse in the Bathroom

Magna Carta in 20 Places

First published in 2017

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2017

All rights reserved

© Derek J. Taylor, 2017

The right of Derek J. Taylor to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law ac.cordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 8488 1

Original typesetting by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

1

Hastings, Sussex. No jackboots please. We’re English

2

Deerhurst, Gloucestershire. Are the English bastards?

3

Farne Islands, Northumberland. The Vikings give us dirt, eggs and fog

4

The Trip to Jerusalem, Nottingham. England, the Normans’ backyard

5

Runnymede, Surrey. Tyranny, treachery and liberty

6

Longthorpe, Cambridgeshire. We know our place

7

Chamber of the House of Commons, Westminster. A funny form of democracy

8

Oxford. Bad days

9

Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire. Bardolatry

10

Stow-on-the-Wold, Gloucestershire. Massacre in Middle England

11

Newby Hall, North Yorkshire. Rational, rich and rowdy

12

HMS Victory, Portsmouth. ‘England expects ...’

13

Barrow Hill Roundhouse, Derbyshire. Steam, iron and ingenuity

14

The Back to Backs, Birmingham. English monstrosities

15

Bamburgh Castle, Northumberland. Forwards to the past

16

Liverpool Docks. By jingo!

17

Epsom Downs Racecourse, Surrey. Return ticket to death

18

Imperial War Museum, Lambeth. Mechanised slaughter

19

Duxford, Cambridgeshire. A people’s war

20

Dover, Kent. The lock and key to England

Acknowledgements

1

Hastings, Sussex.

2

Deerhurst, Gloucestershire.

3

Farne Islands, Northumberland.

4

The Trip to Jerusalem, Nottingham.

5

Runnymede, Surrey.

6

Longthorpe, Cambridgeshire.

7

House of Commons, Westminster.

8

Oxford.

9

Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire.

10

Stow-on-the-Wold, Gloucestershire.

11

Newby Hall, North Yorkshire.

12

HMS Victory, Portsmouth.

13

Barrow Hill Roundhouse, Derbyshire.

14

The Back to Backs, Birmingham.

15

Bamburgh Castle, Northumberland.

16

Liverpool Docks.

17

Epsom Downs Racecourse, Surrey.

18

Imperial War Museum, Lambeth.

19

Duxford, Cambridgeshire.

20

Dover, Kent.

1

HASTINGS, SUSSEX

NO JACKBOOTS, PLEASE. WE’RE ENGLISH

THE ENGLISH NEVER KNOW WHEN THEY ARE BEATEN

SPANISH SAYING

‘Listen mate,’ says the Saxon soldier, hitching up his sword belt. ‘Never mind about the result on the battlefield. What counts is inside here.’ And he gives a thump on his chain mail where it covers his heart. ‘Inside here, mate,’ he repeats with a glare, ‘we English win every year.’ He’s not joking.

I’ve just arrived at the spot near the south coast of England where Duke William of Normandy defeated King Harold’s Saxon army at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Today is the anniversary of the battle, and our Saxon soldier is one of several thousand individuals who come here every year on this day, dressed in cross-gartered leggings, hand-stitched leather boots, chain mail, shining helmets and armed with spears, swords and battleaxes, just as their ancestors did 950 years ago. He’s a battle re-enactor. And thousands more of us on this sunny day have turned up to watch them fight it out.

Meanwhile, before the mayhem starts, the mood on the vast field below the walls of Battle Abbey is both festive and feverish. There are kids chasing each other, brandishing brightly coloured plastic weaponry. There are parents yelling at them not to get lost, and come and get a burger, and yes, I mean now! And mingling among those of us in jeans, T-shirts and trainers or similar twenty-first-century kit, adults in medieval dress are trying with self-conscious nonchalance to look as though it’s perfectly normal on a Saturday morning in a field in East Sussex to be dressed like an extra from Lord of the Rings.

This is not just a blokeish pursuit. I can see around me plenty of female camp followers as well, mostly in long brown frocks made from rough cloth and wearing white pointed hats with silky material swirling around their shoulders. There’s one here now, hanging on the arm of our Saxon soldier.

What I’d said to him – after a pleasant and informative conversation about the handiness of the short-sword hanging from his waist – was, ‘Good luck this afternoon in the battle,’ and I’d added with a stagey wink, ‘You never know, maybe this’ll be your year to beat the Normans.’ Not a side-splitter, I realise, as Saxon jokes go. But his answer is collectable. ‘In here,’ (he taps his heart) ‘we English always win.’ – such a poetic sentiment from a man dressed as an old-time thug. It tells of his pride in his country, a nation somehow able to snatch glory from the humiliation of defeat. So, waiting till he and his damsel have strode on so I won’t offend him further, I pull out a notebook and biro to scribble down a couple of lines about the encounter.

A panel from the Bayeux Tapestry, dating from the 1070s. The idea that Harold was hit in the eye by an arrow is probably a myth, started later by the Normans who wanted to portray his death as God’s judgement on an illegitimate ruler. Then in the eighteenth century, during overenthusiastic restoration of the tapestry, an arrow was added where there may not have been one originally.

I’ve come here today not just for the entertainment. I’m on a quest for first-hand evidence that might help unravel a puzzle. Who, exactly, do the English think they are? Where do they come from? What is it in their history that makes them so … English? And what does being English mean? To find answers, we’re going to travel through time and space. We’ll explore twenty places that have played a role throughout history in forming the national identity of the English. Our journey will take us from an Anglo-Saxon church to a Second World War airbase, from a Northumbrian island to the White Cliffs of Dover, and in between we’ll be visiting a pub, a racecourse, a slum, a mansion, a battleship and many more places, criss-crossing England through 1,600 years. And at the end of our journey, we’ll ask the unthinkable: does the whole idea of English national identity still have meaning in the twenty-first century? Or have European federalism, globalised commerce and mass migration rendered it obsolete?

***

So why have we come first to Hastings? The reason is simple. The battle fought here in 1066 was the most important turning point in English history. Once the Norman duke, William the Conqueror, had triumphed and been crowned King of England, no jackbooted army of occupation ever goose-stepped through the land. In almost a millennium since that battle on the south coast, England has never again been successfully invaded. Napoleon, Hitler and others have tried. None managed it. That doesn’t mean the English have been free from any outside influence for all those centuries – far from it. As we shall see on our journey, many encounters – both peaceful and warring – with others beyond our shores have all helped mould the English character. Nevertheless, the fact that the country has seen off every foreign attempt to seize the country by force for the last nine and a half centuries has had two effects. It has reinforced the sense of an unchallenged English national identity, and it has established the notion (in English minds, at least) that the English are a free and independent people. The English have a political and social history that goes back in an unbroken line further than that of any other race on earth.

Thus, the Battle of Hastings – defeat as it was for the English – has become a symbol of the nation’s independence. And so here we are today on the anniversary of the battle, along with many thousands of our fellow countrymen, for whom Hastings means… well, that’s one of the things we’re here to find out.

***

The re-enactment itself is due to start at 3 p.m., so there’s time to interview a few subjects first. One of the attractions is a medieval market. Apart from half a dozen food stalls, each with a line of hungry visitors, and one tent selling gifts, as well as the sort of armaments with which the small children are bashing each other, the rest of the tented shops cater for the Saxon re-enactor’s yearning for authenticity. Some sell pointed helmets and heavy belts. Some have got smocks, headscarves and medieval shoes for sale. Others advertise eleventh-century cooking equipment. And another has an array of standards and pennants as used by Aethelwold, Eadwig and other pre-Conquest monarchs.

A man in a green smock is hammering away over a glowing forge, pausing occasionally to explain to a small crowd how you make chain mail. A young woman, whom he refers to as ‘Lady Matilda’, is passing among us. Folded across her arms is a complete coat made of little iron rings interlocked like a loose-knit sweater.

‘How heavy is it?’ I ask her.

‘Over 40 pounds,’ she replies.

‘Good heavens!’ I say. ‘I wouldn’t want to be wearing that while I was trying to run away!’

‘You would if they caught you,’ she says with a grin. ‘Here, hold it.’ And she drapes it across my wrists.

‘Bloody Hell!’ I exclaim, staggering for a moment as my arms sag under the weight.

Further on is an axe shop. The salesman is a young guy who, above the usual chain mail, leather and scabbard, sports a thick growth of facial and head hair at odds with the youthful features they frame. I pick up one of the axes. There are a dozen of them hanging on a rail, each with a black blade and a wooden handle as long as your arm.

‘How much?’ I ask.

‘Sixty-five quid,’ he replies.

‘Sixty-five quid!’ I exclaim. ‘Crikey, it’s expensive, this reenacting game.’

‘Yes,’ he says. ‘You can spend hundreds on the right costumes and equipment.’ I raise my eyebrows in a quizzical expression. ‘Everything – weapons, clothing – has got to look authentic. We’d be letting the side down if we turned out with some tatty old plastic sword and a polyester T-shirt.’

I nod. ‘So, when you say “letting the side down”, you mean your fellow re-enactors?’

‘Yes. And the country. England,’ his voice now slightly raised in irritation at my ignorance, and perhaps at my lack of patriotism.

I feel the need to be defensive. Running my finger down the axe-blade, I remark, ‘Not very historically sharp, is it?’

‘Well, we’re not so authentic that we want to actually kill each other,’ he smiles.

‘So how do you avoid people getting hurt in the battles?’

‘We train,’ he says, ‘at weekends. You’re not allowed to take part in a battle till you’ve been on a course.’

‘A course? You mean with professional combat instructors?’

He nods. ‘And,’ he adds, pausing for emphasis, ‘we have a health and safety officer.’

At that moment, a giant thug of a man arrives at my side. He’s tooled up like a Saxon gangster, smoke drifting from his nose, a cigarette cupped in his hand. Even I am not foolish enough to point out to him that he’s infringing the central rule on anachronistic behaviour.

***

It’s time to grab a sandwich and a good place to see the battle. There’s half an hour to go. Most visitors have been cannier than me. They bagged their spots an hour or more ago on the grassy slope above the roped-off part of the field where the big event is going to happen. The spectators are clearing the picnic remains off their blankets and adjusting their collapsible chairs. Kids are managing – as only kids can – to run about, trip over and eat ice creams all at the same time. I’m relegated to a back row, where I need to stand to get a decent view.

Before us, on the other side of the rope barrier, a man in knitted tie and corduroy jacket (the universal uniform of male history teachers) is walking up and down with a microphone, delivering a lesson on the background and origins of the Battle of Hastings. Creditable as this is, no one’s listening. They’re all gossiping or playing about. It’s just a background drone, like the TV on in the corner during the day.

After twenty-five minutes of this, the mood suddenly shifts. A mob of men – at a rough count about a thousand – in pointed helmets, carrying swords and shields, trudge into view on the right-hand side of the field, and the lecturer promptly switches roles to commentator, ups the tempo of his monologue and shouts through his mic, ‘Let’s have a big cheer, ladies and gentlemen, for Harold – and – the – Saxon – ARMY!’ Everyone around me bawls their heads off.

Two tall young men come and stand directly in front of me so I can’t see.

‘Excuse me, guys,’ I say.

The nearer one turns to me, ‘I do apologise, sir. Please forgive us,’ his excessive politeness making me wonder if he’s being sarcastic. But then, as they both move to one side, he continues, ‘We had not realised already that you your view we are blocking.’

‘No problem,’ I say. ‘Where are you from?’

‘Germany,’ he replies. ‘We are both in London University.’

‘Ah, I see. From Saxony, by any chance?’

‘Ahh, a very good joke,’ he replies. ‘But no, we do not live in northern Germany. But my friend here and I are from Bavaria. It is very nice there.’ And he launches into a detailed, if fractured, account of Bavarian Christmas street markets.

Soon, the Saxon soldiers start to chant something with three syllables which is difficult to make out through the description of Alpine Weihnachtsfest infiltrating my left ear. ‘Excuse me a sec.,’ I say to the student, who bows politely, and I make out the words, ‘God-win-son. God-win-son. God-win-son.’

The announcer explains. ‘The Saxon troops are chanting the name of their king, Harold Godwinson.

Then the chant changes to what sounds like, ‘Oot! Oot! Oot!’ (I’ve yet to meet anyone who knows what that means.)

At this point, the enemy arrive, about a thousand foot soldiers clomping in from the far left. They line up 200 yards from the Saxons, then fire off a few arrows that curl high into the air before making a miserable touchdown in no-man’s-land. ‘Let’s give a big hand now, everybody, for – William – and – the – NORMANS!’

Once the crowd has stopped booing, I turn to the student, who’s now busy videoing the whole thing on his phone, and ask, ‘Do you have anything like this in Germany?’

‘Once I was in a restaurant in Bavaria,’ he replies, ‘where two men dressed up like soldiers of Frederick the Great and demonstrated to the customers their swords.’

‘And that’s it?’

‘Yes, that is the only re-enactment I have seen in Germany.’

I look around for more interviewees. A few yards behind me, three men in red tracksuit tops are standing to attention. Each is holding a pole 9 or 10ft tall from which flutters a red flag with a white lion on it. I trot over to talk to them. As I get close, I see written on their chests, ‘English Community Group (Leicester).’

‘Hello there,’ I say, trying to sound as matey as possible. One of them nods, so he’s the one I address. ‘I’m curious about …’ – I pointedly study the words on his jacket – ‘… the English Community Group.’

‘(Leicester),’ he adds.

‘Forgive me, I’ve not heard of it before.’

He relaxes his shoulders and stands easy. ‘We exist to politely represent the interests of the English community in Leicester and Leicestershire,’ he says.

‘Oh,’ I say. ‘“Politely”?’

‘That’s right, we’re not the BNP.’

‘A-ha. I see. So why is the Battle of Hastings important to you?’

‘We’re dedicated to giving back to the English their unique identity and culture,’ he recites, ‘with a particular focus on our Anglo-Saxon tribal roots.’

‘Oh,’ I say, and I’m just about to point out to him – politely – that the Anglo-Saxon’s tribal roots were in Germany and Denmark, and that the words ‘community’ and ‘group’ both came into English from Old French, when he continues, ‘And another thing: we’re actually anti-racist. We’re challenging institutionalised Anglophobia in Leicester.’

‘Discrimination against whites?’

‘Discrimination against Anglo-Saxons.’

At this point, there must be an incident on the battlefield, because the cheering starts again, and the Anglophiles (Leicester) begin a co-ordinated, ‘Oot! Oot! Oot! Oot!’

I nod my thanks and drift back. Our commentator is now urging us on. ‘C’mon, ladies and gentlemen, let’s hear it for the English,’ he shouts, adding in exasperation when he doesn’t get the required excited response, ‘These men are fighting for your freedom!’ Is he from Leicester, I find myself wondering.

But he has no need to fret. The two armies stamp towards each other, banging their lances and swords against their shields, and shouting unintelligible eleventh-century oaths. You can almost hear the collective lips of the crowd smacking at the prospect of blood and mayhem. Near me, a young woman with black hair and a lip ring is jumping up and down on tiptoes, as the gap between the mighty forces of King Harold and Duke William of Normandy narrows to a broadsword’s length. ‘We hear the terrible noise of battle,’ according to the commentary, ‘as bones crack and men die bloody deaths!’

The crowd in front of me crane their necks for a glimpse of the cracking and dying. This sort of thing goes on for about ten minutes. The commentator then sorts out any confusion in our minds: ‘The English are winning. The Normans still can’t break the English lines! Let’s hear it for the English!’ (Scattered ‘Oots’, off left.)

‘Oh no, ladies and gentlemen!’ the dread words then come over the loudspeaker. ‘Oh no, who do we have here with an arrow in his eye? It’s King Harold. He’s fallen. He’s been killed!’ The spectators in front of me rise as one from their foldable chairs to try and glimpse the appalling fatal injury, thus blotting out my own view. ‘The news of Harold’s death spreads through the English lines,’ continues the commentary. ‘The English spirit is sapped’ – this in a tone of desperate sadness – ‘and the Normans are emboldened by this terrible tragedy for England.’ As the crowd before me sink back into their downcast seats, I see the melee start to nudge back towards the Saxon camp. Then the retreating soldiers turn and break into a stumble, leaving behind half a dozen corpses.

The action’s over, and the field is occupied by the victorious cavalry, who are galumphing about like Labradors on a beach. A mounted knight in a bright red smock comes close to us, waving his sword in the air. ‘Vive le duc Guillaume! Victoire!’ he shouts. We hiss him and whistle.

It’s then I catch sight of the Saxon soldier I’d first interviewed. He’s standing just the other side of the rope barrier with the blade of his short-sword hanging forlorn below his limp arm. He waves two fingers at the triumphant Norman, and calls out, ‘You wait. We’ll see you later at Agincourt!’ I can’t tell if he’s joking or not.

***

So what does all this tell us about who the English think they are? Clearly, a mild brand of nationalism has been on offer at Hastings today, and we’ve drunk it in. The crowd may not by and large have listened much to the commentator’s warm-up routine, explaining events that led to the battle. But he did establish his credentials as a historian, someone who is well informed. So his remarks, when he started to get us excited about the re-enactment, were likely to carry weight. And his words were telling. He presented the show not as a fight between two ancient tribes. Instead he talks about it as a battle which the crowd can get involved with, a tussle between traditional rivals, the English and the French. He urged the crowd, ‘C’mon, ladies and gentlemen, let’s hear it for the English. These men are fighting for your freedom!’ It’s ridiculous, but the thousands of English spectators at Hastings today loved it and cheered. We all knew – or thought we did – that if it hadn’t been for one unlucky arrow in the king’s eye, the English would have won. And of course, in at least some of our hearts, we did.

On the face of it, our Saxon soldier’s heart-tapping remark is illogical: ‘The result on the battlefield doesn’t matter. In here, mate, we always win.’ The bare truth is that if you lose on the battlefield, you’re likely to be invaded, possibly killed and probably oppressed by a victorious enemy. So in what sense do you win? The suggestion must be that the English always behave nobly and heroically even when they’ve got their backs to the wall, staring death or defeat in the face. It’s a belief that was held by Victorian soldiers at the time of the Empire, as we shall discover later on our journey. And for our Saxon soldier, being a re-enactor at Hastings enables him to be a part of a long and glorious English tradition, even if just for the afternoon.

Of course, some of us here today took it more seriously than others. The adherents of the English Community Group (Leicester) seem to be revering the Anglo-Saxons as the purest example of Englishness, and so regarding all later generations as some sort of corruption. If nothing else, it goes to show that English national identity is not always about rational argument, it can be about emotion. In this case, about ignoring the far-reaching influence of the Normans and their successors on English history, culture and language, as well the myriad of other developments over the past 950 years that have shaped and changed the English and made them what they are today. The English Community Group (Leicester) are drawing strength from what they regard as some long-lost golden age in England.

These chaps standing to attention beneath their fluttering white lion standards, are of course a tiny minority of the English. But what the English Community Group’s members do have in common with many more of their fellow countrymen is a strong feeling that it’s something in our history that makes us who we are.

Social psychologists argue that national identity – that is, the particular values that a national group holds dear and the traditions they have of behaving in a certain way – derive from that nation’s history. Psychologists believe that distinctive groups of people have what’s called a ‘collective memory’ of their past. In other words, there’ll be a popular idea about what it is in the nation’s history that’s important. If, for instance, one group of people celebrate those of their ancestors who travelled the globe buying and selling goods, they’ll say, ‘We are a great trading nation.’ Or other folk might choose to remember their ancestors’ struggle against oppression, and then they might say, ‘We value our freedom. We’re prepared to die defending it.’ And these selected bits of history then get reinforced in the popular mind. To quote the psychologists again, they are ‘memorialised.’ That might mean they’re celebrated at mass events – like battle re-enactments for instance, or armistice ceremonies. Or else, a nation’s key achievements in history are ‘memorialised’ in the places where they happened: at historic sites that people can visit, cherish, feel proud of and sometimes volunteer to look after. And this is why we’re going to investigate English national identity by visiting twenty places that tell the story of how the English came to have certain values and why they behave as they do.

It’s a story full of mystery. The English – as you’d expect from a race 1,600 years in the making – are a complex lot. They’ve often behaved in contradictory ways. So for instance, the English place the highest value on their democracy but took centuries to give everyone the vote. They’ve been seen as tolerant, even though at times in their history they’ve persecuted minorities. They’ve loved political stability yet have fought among themselves. They’ve been eccentric and funny on the one hand, conformist and straight-laced on the other. They’ve revered the rule of law, but put a military dictator’s statue outside Parliament. They’ve fought like lions in wartime, while making hatred of war respectable. The English have managed to be both self-centred and outward-looking, puritanical and permissive, arrogant and benevolent. And for much of their story, the English have been divided by a snobbish class system yet united against all foes. Bewildered? Don’t worry. We’ll sort it all out on our journey.

But we have to watch out. As on any adventurous exploration, it’s easy to get lost. Before us is a crossroads, with signs pointing one way to ‘Englishness’ and the other to ‘Britishness’. You may indeed be asking: ‘Why isn’t this book called, Who Do the British Think They Are?’ After all, no one has a passport that says, ‘Nationality: English.’ As we shall see on our journey, not only the English, but foreigners too, in recent centuries have often got the words ‘English’ and ‘British’ mixed up. They say ‘English’ when they mean ‘British,’ and ‘British’ when they mean ‘English.’ Why they do that is one of the puzzles we’ll be unpicking, and incidentally learning a lot about the English in the process.

The fact is that Britain is a ragbag, and a comparatively recent ragbag at that. The Scots were a separate nation until 300 years ago and, of course, are more and more asserting their independence. They sometimes dismiss the English as ‘Sassenachs’, which, as any dialectician will tell you, means ‘Saxons’. The Welsh are understandably proud of their own language, culture and history. And Northern Ireland or Ulster, depending on your politico-cultural standpoint, has existed as a province of the United Kingdom for only a century, and its citizens are still sometimes divided as to which side of the Irish Sea their loyalties lie. The Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish/Ulster folk can all claim they’ve got their own identities. It’s true that the English have often been subject to many of the same influences as the other UK home nations. But the reaction of the English to those influences has not always been the same. The Brexit vote is an obvious example. The English are part of Britain, but still often see themselves as a separate group with their own values and their own way of doing things. So there’ll be no confusion for us. Our journey is along the road signposted ‘English.’

***

So we’d better get moving. Where did the story of the English begin? Our Hastings re-enactors were right – the Anglo-Saxons were English, the first to call themselves that. So who were they? And do they have anything much to do with the English today and their sense of who they are? To find out, we’re going to visit a skyscraper. A medieval skyscraper. And if you think that’s improbable, you are – like me – in for a surprise.

2

DEERHURST, GLOUCESTERSHIRE

ARE THE ENGLISH BASTARDS?

NO, THEY ARE NOT ANGLES, BUT ANGELS

POPE GREGORY I (540-604)

So here I am, parked up by the church gate and biting my bottom lip. It’s the view across the huge graveyard that’s giving me doubts. I can’t take my eyes off the side of the church. It’s such a disappointment. Don’t get me wrong – it’s impressive. Too impressive. I’ve come to the village of Deerhurst in Gloucestershire to investigate the Anglo-Saxons, and to see in what way, if at all, these first English had any influence on the national identity of those who live in this land today. The church here is said to be one of the best preserved Anglo-Saxon buildings in England. Its architecture and art claim to be among the finest expressions of Anglo-Saxon culture from more than 1,200 years ago – a primitive age in the construction industry.

But by a quick calculation, I’d say the edifice before me now is the height of a seven-storey building, way beyond the capabilities of eighth-century stonemasons. It looks as though it dates from much later. Maybe the guidebooks are exaggerating and there’s only the odd bit of stonework at knee-level that’s actually Anglo-Saxon. Or could the explanation be that Deerhurst has got two places of worship, and I’ve come to the wrong one? That must be it. I know the original church was part of a priory. I probably took a wrong turn, back on the outskirts of the village, where it said: Left, ‘To church and chapel.’ Right, ‘To Priory Farm B&B.’ ‘Left’ looked a cert. But maybe I should have gone right. The remains of the Saxon church could be somewhere that way, near Priory Farm.

And then there’s the church gate itself. It’s like no church gate I’ve ever seen. It’s a shoulder-high sheet of heavy, grey steel and looks more like a barrier that could be electronically slammed against suicide bombers, than the welcoming gateway to a tranquil country churchyard. Then I realise: it’s a floodgate. And this makes me even more convinced I’ve come to the wrong place. The idea that eighth-century workmen could not only erect a seven-storey building, but do it on marshy land that’s prone to flooding … well, it’s ridiculous.

I decide to have a closer look anyway, just to be sure, and head down the path through the graveyard, tutting all the way at life’s irritating confusions. The first thing that catches my eye inside the door at the west end of the building, is a stone carving above the inner doorway. It’s a fresh orangey yellow, with simple lines. Looks very modernist. The kind of sculpture Anthony Gormley is famous for. All very well in its place. Probably the idea of some vicar here who thinks he’s being ‘with it’.

‘Hello there. Can I help?’ I hear a voice behind me, and turn. It’s a woman, neatly dressed in long black cardigan and grey flared skirt.

‘Lovely church,’ I reply. ‘I’m just having a browse.’ Having a browse! Where do I think I am? Marks & Spencers?

‘I see you’re admiring our carving of the Virgin and Child,’ she says. ‘The Christ child is represented as still in the womb.’

‘Hmm,’ I say, and, not wishing to be rude, add in an encouraging voice, ‘So who’s the artist?’

‘Wouldn’t it be wonderful to know?’ she replies. ‘I suppose some Saxon mason with a talent.’

I’m stunned, and repeat with a disbelieving frown, ‘It’s Saxon?’ She nods, and I take a closer look. ‘Crumbs!’ (You’ll notice that in my concern to be respectful of the sacred surroundings, I’ve resorted to Enid Blyton type expletives) ‘I thought …’

‘I know. Incredible isn’t it? There’s been scientific analysis carried out, and we now know that originally it would have been brightly coloured. There are tiny remnants of red paint.’

So this is my first mistake. But, sometimes, it’s a delight to be wrong. And I’m starting to wonder what else I’ve not understood.

‘Has the sculpture been moved … from … from …?’ I stutter.

‘I don’t believe so,’ she interrupts.

‘So parts of this church are Saxon, then?’

‘Goodness, yes,’ she says. ‘Come outside and I’ll show you.’ We go back along the path and she points upwards. ‘See the herringbone pattern…’ – this is at the top of the outside wall of the nave – ‘…that’s Saxon.’

‘But that’s twenty-odd metres high! How could they do that in, what? … AD 790?’ I shake my head in wonder at all the benefits of modern structural engineering they lacked back then, from mechanised diggers, steel joists, giant cranes and reinforced concrete to stress-test computer programs, not to mention hi-viz jackets and safety helmets. ‘By the standards back then,’ I remark, ‘building this place must have been on a par with putting up a hundred-storey skyscraper today!’

My guide smiles with pride. And I tick off Mistake No. 2.

‘I know, it’s amazing,’ she says. ‘And what’s more, this is a flood plain. The river’s just over the other side of that field, so they had to put in foundations that would cope with marshy ground as well. We got terrible floods here in 2007.’

By now I’m prepared, and I just nod as though I knew that all along, though clocking Mistake No. 3 in my head. I’d better go for the fourth error of the day.

‘And one other question,’ I say. ‘Where was the original priory?’

‘Why, right here,’ she says, and leads me back along the outer stonework of the church, and directs me to look over a 4ft-high wall. It’s an unexpected sight. Tacked onto the back of the church is a long, two-storey house with Tudor windows. Its garden – complete with shrubs and a lawn dotted with kid’s trikes and a couple of tents – is set against the church wall. ‘This was the cloister from the ninth century on,’ says my guide. ‘And the house was part of the monastery. It’s now Priory Farm.’

‘Priory Farm, as in Priory Farm B&B?’ I ask. She nods. ‘But the sign back down the road pointed in the opposite direction,’ I complain.

‘That’s winding country lanes for you,’ she says with a smile. I cover my embarrassment with a quick fig leaf of theatrical laughter.

We introduce ourselves. Alice, it turns out, is a local historian. ‘Actually, I’m meeting some pilgrims from Liverpool arriving any minute. Perhaps you’ll excuse me. There are a couple of things I need to get ready.’ I thank her and off she goes.

***

So who were the people who built this magnificent structure? Should we call them English? Or Saxon? Or Anglo-Saxon? Or what? And regardless of what name we choose to give them, do they have any connection with English people today, other than the fact that they back then, like some of us now, lived and prayed in this Gloucestershire village?

The Anglo-Saxons (lets stick with that title for a minute) had arrived here over 300 years before the heroic foundations for this church were dug. In the early fifth century, the Romans packed their baggage trains and, after their 400-year occupation of this land, left for ever. They deserted the country to go and defend their empire against the assaults of the Goths and other people branded by the Romans ‘barbarians.’

The ancient Britons, now without a Roman army to see off attacks from neighbouring tribes of Scots and Picts, decided to call in military help from Continental Europe. And in answer to that plea, in the year 449 on a beach near Ramsgate in Kent, three long, open-topped rowing boats arrived – according to legend – under the command of two brothers, Hengist and Horsa. They were followed by many similar groups who beached their boats on these shores and set off inland armed with spears, short swords and shields. No one was recording at the time exactly where they’d come from, or at least no such contemporary writings have survived. The best we can do, in terms of the written word, is 300 years later, when the chronicler-monk, Bede, put pen to parchment. He wrote: ‘Those who came over were of the three most powerful nations of Germany – Saxons, Angles and Jutes.’

The Saxons and the Angles came – roughly speaking – from an area now part of northern Germany, and the Jutes from Jutland in northern Denmark. The ancient Britons may have regretted inviting them over. As more and more Germanic tribespeople arrived from the east, they turned their weapons against the Britons themselves. Year by year, the newcomers gained the upper hand. They weren’t just soldiers, they were farmers too, and they settled further and further to the west. By the time Bede was writing, their descendants ruled the whole land.

Neat lines on a map belie a complex pattern of invasions and peaceful migration by many different groups during the fifth century.

It’s significant that Bede calls his chronicle, A History of the English People. And once he reaches the final paragraphs of his work, he no longer uses the word ‘people’. Instead he refers to the ‘English nation.’ A leading twentieth-century historian of the Anglo-Saxon period, Patrick Wormald, wrote that Bede had a decisive role in ‘defining English national identity’.

Bede of course was Christian. Hengist, Horsa and those first migrants were not. The Angles, Saxons and Jutes worshipped the ancient Norse gods. Their ghosts are with us still. In place names like Wednesbury in the West Midlands, meaning fortress of the chief god Woden, or Thanet in Kent, the clearing of Thunor, god of thunder. And today, though we’ve stopped worshipping the old gods, we still recite their names every day of the week. Well, almost every day. Tuesday is Tiw’s day, Tiw being a one-handed Anglo-Saxon god who was renowned for his skills in single combat. Wednesday belongs to Woden himself, and Thursday to Thunor. Woden’s wife Frig gave her name to Friday. The Anglo-Saxons also worshipped the sun and the moon, hence Sunday and Monday. Only Saturday was left as a reminder of the Romans and their god Saturn.

But within 150 years, the terrifying warrior gods of the first Anglo-Saxons came under attack. It was a war they would lose. In the year 597, a 43-year-old unarmed Italian arrived on the south coast and started to talk about there being only one god, who had a son. St Augustine established his base at Canterbury, and, remarkably, within seventy years Anglo-Saxon England was converted, more or less, to Christianity.

The Anglo-Saxons had brought with them a rich artistic culture. In 1939, in a field just east of the little Suffolk town of Woodbridge, archaeologists uncovered the remains of a small ship that had lain buried in the earth for thirteen and a half centuries. The excavation of the Sutton Hoo ship and of several burial chambers nearby brought to light some beautiful and historically important objects, now housed in the British Museum. They included a fearsome metal helmet with mask covering the face, decorated swords, various buckles and shoulder clasps fashioned with densely interwoven patterning in gold with inset garnets, ornate belts, and a shield adorned with a bird of prey and a flying dragon, and much, much more. The archaeologist and art historian, David M. Wilson has said that the metal artefacts found in the Sutton Hoo graves were ‘work of the highest quality, not only in English but in European terms’. Their conversion to Christianity saw the Anglo-Saxons’ artistry and skill thrust upwards in a new direction. They built churches, some of the most magnificent structures in Europe since the collapse of the Roman Empire. And still, today, in over 430 villages and towns across England, you can find a church with substantial parts – walls, columns, window slits, archways, carvings and other stone decorations – just as they were when the Anglo-Saxon masons fashioned them. St Mary’s, Deerhurst is one of the finest such structures.

***

As I enter the nave, I find myself among one or two other visitors. There’s a middle-aged couple in shorts and hiking boots. He’s taking photos, while she’s being pulled along by a panting West Highland terrier.

‘Terrific church,’ I say, hoping to follow up with something a bit more penetrating.

They both nod with ‘Lovely,’ and, ‘Magnificent, isn’t it?’

‘I’m a stranger here myself,’ I say. ‘May I ask what’s special for you about the place.’

‘I wanted to photograph the font,’ says the man, pointing to what looks like a huge, stone handleless teacup standing just inside the door. ‘It’s the oldest one in England,’ he adds.

‘Really?’ and I stare at it in admiration. Its decoration is a maze of spirals with delicate leaves that scroll around its lip and base.

‘I don’t know if you’ve come across this design before,’ says the woman, ‘but the Saxons, and the Celts before them, believed that the Devil travels only in straight lines, so a wiggly decoration like this was supposed to stop Satan entering the baptised baby.’

I step forward, the pattern tempting me to feel its smooth contours. That’s what I do, and with a shiver realise that my fingers are following the same grooves and bumps that the nameless Saxon mason chipped out from a single piece of stone – maybe right here where I am now – 1,200 years ago.

‘Amazing, huh?’ says the man. ‘We’re talking fifty generations back when this was first made.’

‘Are Saxon churches a special interest of yours?’ I ask, glancing at both of them, to encourage a joint answer.

‘Not necessarily Saxon,’ she replies. ‘We always try to include a couple of old churches on our walks.’

‘You never quite know what fantastic surprises you’re going to find,’ her partner adds. ‘Maybe some beautiful piece of wooden carving 800 years old, or a little window where lepers had to watch mass being said, or a dark underground vault where monks hid during the Reformation.’

‘Hmm, I know what you mean,’ I say.

‘We’re so lucky in this country,’ says the woman. ‘So many beautiful old churches.’

The man laughs. ‘Who’d want to go the Spain or France or wherever, when you’ve got all this …’ he looks up at the soaring nave above our heads, ‘… right here on our doorsteps?’

We all smile our agreement and part.

The nave must be over 15m up to its roof. But I am a little disappointed. It’s light and airy. The Anglo-Saxons didn’t do light and airy. In the eighth century it would have been dark and stuffy, the only sunlight flickering in through a couple of little triangular holes close to the roof. It’s been changed recently. ‘Recently’, that is, in Deerhurst terms. We’ve got to blame the abbots of nearby Tewkesbury, who a mere 500 years ago had four huge, square Perpendicular windows knocked through into each side wall.

Alice spots me frowning up at the mid-morning sunshine. I explain my desire for more Saxon gloom, and she suggests, ‘Pop round to Odda’s Chapel. I’m going to be giving a little chat to the pilgrims in about ten minutes. You’d be welcome to sit in. Just time for you to go and have a look.’

She explains that Odda’s Chapel was built 200 years later than the church, then at some point it disappeared, and was thought to have been knocked down. But in 1865 the vicar of Deerhurst, one George Butterworth, pieced together some clues and realised that the kitchen and main bedroom of a nearby home were actually the chancel and nave of a Saxon chapel. It had been built by Earl Odda to commemorate his dead brother. The Reverend Butterworth set to work and restored it as close as he could to what it would have been like in the eleventh century.

My route takes me along the graveyard path, and through a second floodgate. As I round the corner, an extraordinary vision hits my eyes. It’s an oak-framed Tudor house – all white plaster and black criss-crossed beams, like Shakespeare’s birthplace. But the odd thing is that stuck onto its end, like a snail eating an ice cream, is what looks like a dour grey-stone barn. A small metal sign tells me this is Odda’s Chapel. I pass through its gaping door-hole, and all is murky and glum. As it would have been back in Odda’s day. No light, no pews. I suck in its mysterious misery for a few minutes, so I can return to the nave of the main church with renewed and darkened Saxon eyes.

Back outside St Mary’s, a jumble of pilgrims awaits. When I hear that word, ‘pilgrims’, I think of the Nuns’ Priest and the Wife of Bath roistering down to Canterbury, or of tiringly joyful young backpackers foot-slogging through Northern Spain to Santiago de Compestela. These Liverpool pilgrims are retirees in blue anoraks and have come in a coach.

We all go and sit in the front pews, me screwing up my eyes to peer at the best-preserved double-headed, Saxon window opening in England. Compared with the huge sixteenth-century perpendicular windows along the side of the nave, it is tiny. But the neatness and simplicity of its shape suggests a strength and a modesty lacking in their big younger brothers. Alice welcomes the Liverpudlians, then says, ‘And today we also have with us a special gentlemen, Mr Jepherson, who just happens to be here visiting with his wife. It was his great-grandfather who rediscovered our wonderful font!’ He nods in acknowledgement from a pew across the aisle.

What does she mean, ‘rediscovered’? But there’s no chance yet to ask Mr Jepherson, because Alice is explaining about the painted Saxon beast heads carved from stone by the entrance door. They’ve got snarling nostrils and eyes that spear you to the spot: works of art in any age. But what have they got to do with Christianity, I wonder. Of course, the early churchmen were clever enough to add a sly suggestion of the old-fashioned paganism to make the new-fangled religion more swallowable by the illiterate common folk.

At last, we break up and I go and introduce myself to the Jephersons – his name’s Ken. What’s his connection exactly with the font?

‘Well,’ he replies, ‘I was born in Deerhurst; we live in York now and we’re just down on holiday in the Cotswolds. And the story in the family was that my great-grandfather …’

How St Mary’s, Deerhurst, would have looked in Saxon times. Note the tiny slits to let in light and the balcony where the monks would display holy relics to villagers and pilgrims on feast days. (By kind permission of ©Maggie Kneen)

‘It was on your mother’s side, wasn’t it?’ his wife interrupts.

‘That’s right,’ he says. ‘It was around the turn of the last century, and apparently he found the font on one of the farms nearby.’ He pauses for effect. ‘It was being used as a pig trough.’

I give a gasp of disbelief. ‘But you know this is the oldest known Saxon font in the country,’ I say, ‘and it’s the finest too.’

Alice has joined us and says, ‘Fantastic, isn’t it? It was probably ripped out either during the Reformation or by Cromwell and the Puritans. But they left the base in position, so after Mr Jepherson’s ancestor rediscovered it, it was put back exactly where it had been twelve hundred years ago.’

‘And I was baptised in it,’ says Ken.

Who wouldn’t be proud? I thank him and his wife.

As the pilgrims head for the door and back to their bus, I find myself standing next to Alice. They thank her and shake her hand. Several of them thank me and shake my hand. For a moment or two, I feel Deerhurst is my church. Which, of course, it is.

***

Churches are unique. The extraordinary thing about St Mary’s, Deerhurst – like all medieval churches – is that it’s still today used for the same purpose as it was over 1,200 years ago when it was built. If the words ‘living history’ have any meaning, it’s to describe medieval churches. A parish church is not a museum, nor a castle that’s open to the public ‘10 till 6 (excl. Weds)’: It’s a working building that tells us about our history. In England, 40 million visits a year are paid to churches by people for that very purpose: not to worship, nor see a friend wed or buried, but to admire the beauty and marvel at the history of the country reflected in these places. There’s even a phrase for it nowadays. It’s called ‘church tourism’. Deerhurst and its like are the perfect example of how we – in the words of the social psychologists – ‘memorialise our past’, and thereby create a collective memory, what makes a national identity.

That memory, however, does not always square with the way historians see things.

We often think of the Angles, the Saxons and the Jutes – perhaps in a story started by Bede – as national armies who systematically drove all the ancient Celtic Britons west until they were confined to the Welsh mountains, the Lake District and Cornwall. It’s a version that sees the English born of pure Anglo-Saxon blood (the Jutes get lost in this account).

Historians today see it differently. For a start, the invaders would have arrived in small parties, and probably wouldn’t have identified themselves as Angles, Saxons or Jutes. They would have been more likely to see themselves as followers of Aethelulf, Stithwulf or whoever. So the town of Reading for example is where the people led by Read (the red one) settled.

Even the names, Angle, Saxon and Jute, probably didn’t indicate distinct tribes. The Jutes, for instance, didn’t come directly from Jutland, but had been wandering around coastal areas to the south for several generations, intermarrying and picking up local religious and cultural customs – so much so that some historians think they shouldn’t be separately considered at all. And then there were the Saxons. The word needn’t have had anything to do with a race of people. It described men who carried a particular kind of short sword in battle, called a saex. That meant, for example, that an Angle who armed himself with a saex was a Saxon.

But perhaps most startling is what recent research has revealed about the ancient Britons, those people whom – legend has it – the Anglo-Saxons drove out, to the last Celtic family, and replaced in what became England. The arrival of DNA analysis has revealed what one scientist has called a ‘truly stunning’ picture of who the ancient ancestors of the English were. Researchers from Oxford University have investigated the genomes of 2,000 white English people whose four grandparents were all born in the same area of England. The scientists also conducted a similar survey of 6,000 people from western Continental Europe. Then they compared the two. The results surprised everyone, geneticists and historians. By far the biggest grouping of English people – an astonishing 45 per cent – had a bloodline going back not to the Anglo-Saxons but to France. ‘Ah,’ you might say, ‘that must be the Normans.’ But it’s not. It mainly represents people who migrated from the Continent to England even before the Romans, sometime after the last Ice Age, 10,000 years ago. So, if 45 per cent of modern English DNA is French, how much is Anglo-Saxon, i.e. English? The answer is a less impressive 20 per cent. So how did that come about?

Once the small bands of Anglo-Saxons arrived, it’s likely there was no one pattern to what happened next. Undoubtedly, in some places, a victorious troop of Anglo-Saxons would have chased away the defeated Britons and their families. But elsewhere, the natives stayed on, often moving to the safety of a nearby hill. It’s true that some ancient Britons did flee to Wales and the far south-west, though probably not a majority. More stayed, accepting – perhaps reluctantly – the rule of their new masters. Then, as the generations passed, they would intermarry and merge until it was impossible to recognise anymore who was descended from the ancient Britons and who from the Anglo-Saxons. So the English nation had a muddled birth. We can’t be quite sure who its parents were. The English are not thoroughbreds. They’re not pure Anglo-Saxons – and they weren’t so even back in the early Middle Ages.

But this leaves another puzzle. Given that so many of the Celtic ancient Britons stayed on, you would expect that the old Celtic language would have been absorbed at least in part by the conquering Anglo-Saxons. That’s what often happens in such circumstances. But this time it didn’t. The Celtic language seems to have been all but wiped out in what became England. Modern English can count on one hand the number of words that came from Celtic, and even they are not in daily use. There’s ‘dun’ meaning grey-brown, ‘crag’ for a rocky point, ‘broc’ for badger – and that’s about it. There’s no satisfactory answer to this conundrum.

What makes it even more puzzling is that Celtic words have survived in hundreds of England’s place names. For instance, Leeds, Avon, Arden are pure Celtic, while many towns, villages, cities and counties can trace at least part of their names back to the ancient Britons. Manchester for instance, from the Celtic mam, a breast-like hill. Lincoln, from lin, a lake. Berkshire, from bearroc, a hilly place. And over 200 small towns and villages in the south of England, from Combe Bottom in Surrey to Compton Basset in Wiltshire, are still celebrating their Celtic origins in a valley or combe. However, we shouldn’t run away with the idea that all these places somehow remained islands of Celtic life in an Anglo-Saxon sea. More likely, the Anglo-Saxon rulers just found it too much trouble to change some of the old names. So they stuck.

The Anglo-Saxon language, on the other hand has come down to us today with great force. It’s arguably the most powerful current that’s flowed down the ages through the English language. Many thousands of words that we commonly use today have their origins in the Old English of the Anglo-Saxons. Here’s a selection: above, baby, crash, dog, eat, fly, goal, hat, indeed, jaw, kidney, lick, moon, narrow, ought, plight, quake, rake, shop, tide, up, vixen, woman, you. And many Anglo-Saxon place names too have come down to us. Anywhere with -ford in it, meaning a shallow river crossing, like Stamford or Chelmsford. Or -ham, meaning in Anglo-Saxon a village, revealing the humble beginnings of Birmingham. -hurst, as in our own Deerhurst, is a wooded hill. Henley’s -ley is a forest clearing. -mer in Cromer is a lake. And those who have been bored waiting for their flight at Stansted airport may not be surprised that it means ‘stony place’ in Anglo-Saxon.

The Saxons also identified themselves in the wider land they occupied. Essex being East Saxons; Sussex, denoting the South Saxons; Wessex, the West Saxons; and Middlesex – you get the idea.

And this brings us to where the terms ‘England’ and ‘English’ came from. You’ll have noticed that in the county names above the ‘a’ morphs into an ‘e’. It’s Essex not Essax. So English comes from the Angles. Why, we may wonder, the Angles rather than the Saxons? After all, we talk about Saxon churches, not Angle churches. No one’s quite sure, but one theory is that in order to make a distinction between the two sorts of Saxons – those that had stayed in Germany, and those that had migrated across the sea – the latter were referred to by Latin writers as the Angli Saxones, that is the Anglish Saxons – the Saxons who associated with the Angles during the great migration to these shores, as opposed to the Old Saxons who had remained in Germany. Our influential friend, Bede, writing in the eighth century, abbreviated it sometimes, and talked just about the ‘Englisc’ (the ‘a’ now having started to mutate to ‘e’), clearly referring to the inhabitants of the whole country.

The nation itself had to wait rather longer for its name. Not till the eleventh century, 600 years after Hengist, Horsa and the first Anglo-Saxons had arrived, did chroniclers start to write of ‘Engla lande’ or sometimes ‘Engolond’ or ‘Ingland’. And it was another 300 years before these variations sorted themselves out to become England. The world should be thankful that the country took its name from the Angles and not the Saxons. If it had been the other way around – and given the ‘a’ to ‘e’ shifts in Essex and Sussex – the land of Shakespeare and Queen Victoria might have been called Sexland. And what would that have done for English (Sexish?) national identity?

***

So, were the battle re-enactors of Hastings exaggerating when they felt themselves to be Anglo-Saxon?

It was not unreasonable to make the words ‘Anglo-Saxon’ and ‘English’ interchangeable. The English didn’t exist when Hengist and Horsa first turned up. But by the time the Normans took over, 600 years later, the two Anglo-Saxon brothers’ successors were commonly called English. So, what have the English today inherited from the Anglo-Saxons?

If we limited our question, ‘Who do the English think they are?’ to the television search for blood ancestors, the answer has to be: we’re not very Anglo-Saxon. At most, only one fifth of our DNA can be traced back to our first forebears. The English are more Celtic than Anglo-Saxon when it comes to ancestry.

But, if we’re talking about the English language, then the English today owe a lot to the people who built Deerhurst church. And, what’s more, the heart of our language is Anglo-Saxon, still today. Then there are those 430 Saxon churches. They’re part of England’s heritage: beautiful survivals from a history that the people of England feel are special to them.

And that word ‘feel’ is significant. When the historian Patrick Wormald talks of the Anglo-Saxon historian Bede as playing a decisive ‘role in defining English national identity,’ I believe he means that if we feel the Saxons helped make us who we are, then – like the battle re-enactors of Hastings – we behave accordingly. That’s national identity.

***

Deerhurst, as well as being the tangible root of English national identity, was the scene of a crucial event in the Anglo-Saxon story. It’s where, in the year 1016, two warring leaders, King Cnut and Edmond Ironside met to negotiate a peace deal. They agreed to carve up the country between them. Cnut would take the north and Edmund the south. But within a year, Edmund was dead – by one account he was murdered while on the privy, and died of multiple stab wounds delivered by an agent of Cnut. Cnut thereby became king of the whole country. Edmund was English, an Anglo-Saxon, and his people were now the subjects of a foreign invader. Cnut was a Viking. To find out what the Vikings did for the English, we’re going to a remote set of islands off the north-east coast of England. It’s where violence and beauty have often met, and – as I’m about to see for myself – blood is still being spilled here.