7,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Open Book Publishers

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Feliks Volkhovskii (1846-1914) was a significant figure in the Russian revolutionary movement of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He lived through pivotal changes ranging from the rise of ‘nihilism’ in the 1860s and the growth of populism in the 1870s, through to the creation of the Socialist Revolutionary Party in the early 1900s. Imprisoned three times before he turned thirty, he spent ten years in Siberian exile before fleeing abroad to join the fight against tsarist autocracy from western Europe.

Following Volkhovskii’s arrival in Britain in 1890, he played a central role in the campaign to win sympathy for the Russian revolutionary movement, editing newspapers and journals including Free Russia. He also helped to smuggle propaganda into Russia as well as becoming one of the most prominent figures in the émigré leadership of the Socialist Revolutionaries. Throughout his life, Volkhovskii was also a prolific writer of poetry and short stories, and was on good terms with many leading literary figures of the time including Ford Maddox Ford and Edward and Constance Garnett.

Michael Hughes’s groundbreaking new biography provides a vivid history of this notable but hitherto neglected figure of both the political and literary worlds. Based on ten years of research in archives across the world and drawing on sources in multiple languages, this masterful biography explores how Volkhovskii’s life illuminates broader intellectual and historical questions about the Russian revolutionary movement. It is essential reading for anyone interested in late Imperial Russia and the Russian revolution.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

FELIKS VOLKHOVSKII

Feliks Volkhovskii

A Revolutionary Life

Michael Hughes

https://www.openbookpublishers.com

©2024 Michael Hughes

This work is licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text for non-commercial purposes of the text providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information:

Michael Hughes, Feliks Volkhovskii: A Revolutionary Life. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2024, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0385

Further details about CC BY-NC licenses are available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web

Updated digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/0385#resources

ISBN Paperback: 978-1-80511-194-8

ISBN Hardback: 978-1-80511-195-5

ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-80511-196-2

ISBN Digital eBook (EPUB): 978-1-80511-197-9

ISBN HTML: 978-1-80511-199-3

DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0385

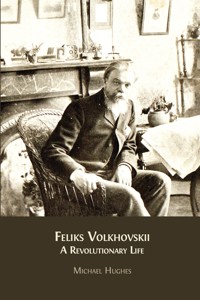

Cover image: Portrait originally published in an obituary of Volkhovskii by Nikolai Chaikovskii in Golos minuvshago, 10 (2014), 231–35.

Cover design: Jeevanjot Kaur Nagpal

Preface

The name of Feliks Volkhovskii is not well-known, except perhaps to a small group of scholars interested in the development of the Russian revolutionary movement in the years before 1917, and even among that small band of aficionados his name pales into insignificance besides far better-known figures like Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotskii. This is partly because Volkhovskii belonged in his final years to the Socialist Revolutionary Party, whose members have often been eclipsed from both scholarly and popular memory, victims of the harsh truth that history remembers the victors better than the losers. The Bolsheviks have by contrast dominated historical attention as the party that took power in October 1917, subsequently transforming Russia from a backward agrarian country into a modern industrial economy, albeit at an almost unimaginable cost in human lives. Even among historians who do study the Socialist Revolutionaries, Volkhovskii remains a surprisingly unknown figure, regularly described as one of the Party’s leaders in the years before his death in 1914, and yet remaining elusive when compared with better-known figures such as Viktor Chernov and Ekaterina Breshko-Breshkovskaia. And, when Volkhovskii has received attention, it has typically been for his role in the London emigration in the 1890s when, along with Sergei Stepniak-Kravchinskii and Nikolai Chaikovskii, he played an important role in the campaign to win sympathy in Britain for the Russian revolutionary movement’s struggle against the autocratic tsarist state. While some younger historians have started to extend discussion of Volkhovskii to other parts of his revolutionary career, he remains a surprisingly neglected figure, seldom warranting more than a footnote or two in scholarly books and articles focused on other aspects of the Russian revolutionary genealogy.

This lacuna in the scholarly literature is regrettable. As the following chapters will show, Volkhovskii lived through some of the pivotal developments in the history of the Russian revolutionary movement, ranging from the rise of the ‘new people’ of the 1860s and the growth of populism in the 1870s to the creation of the Socialist Revolutionary Party in the early 1900s. He was imprisoned for his activities three times before he turned thirty, and spent ten years in Siberian exile, before fleeing abroad like many of his fellow revolutionaries to join the fight against tsarist autocracy from the comparative safety of Western Europe. He was a well-known figure in the revolutionary milieu for nearly fifty years, and while it would be a mistake to overestimate his influence on events, a study of his life can help to illuminate the collective story of all those who fought to destroy the tsarist regime.

There is much about Volkhovskii’s life that remains obscure. Although there is a vast amount of material in libraries and archives around the world that helps to construct his biography, important gaps remain, in part because few correspondents retained copies of Volkhovskii’s letters. This even sometimes extends to the spelling of his name (in later life, Volkhovskii sometimes styled himself Volkhovskoi for reasons that are still not entirely clear). Volkhovskii assiduously maintained files of everything ranging from correspondence through to press clippings, which can be used to cast light on his activities and ideas, but he was inevitably circumspect when writing about certain subjects to avoid the scrutiny of the Russian (and on occasion British) police. Volkhovskii’s biography—personal, intellectual, revolutionary—must therefore be built up from countless fragments into some kind of whole, or at least what José Ortega y Gasset called ‘a system in which the contradictions of a human life are unified’.

I am perhaps an unlikely biographer of a revolutionary like Volkhovskii. Much of my work over the past few decades has focused on individuals who were firmly ensconced in the social and political establishment of their assorted homelands. I have also spent a good deal of time exploring the lives of conservative-minded figures who sought refuge from the chaos of modernity in an imagined world of social harmony and order. And, as attentive readers of this book will probably realise, my intellectual habitus was firmly shaped during the closing decades of the Cold War. Many Russian specialists educated in those years were instinctively inclined to see the failings of the Soviet regime less as a contingent response to complex domestic and international pressures and more as the logical outcome of a utopian project to remake the world out of Immanuel Kant’s ‘crooked timber of humanity’. In reality, of course, the Russian revolutionary movement was, like all social and political movements, made up of countless individuals each with their own beliefs and instincts. That is not to deny that utopian aspirations can prove fatal when they leave the world of books and become a primer for human behaviour. The history of the twentieth century has shown all too graphically that they can. Yet many Russian revolutionaries were inspired less by teleological dreams and more by a hatred of the abuses they saw around them. Feliks Volkhovskii was one of them. If the vast scholarly literature on the Russian revolutionary movement that has been published over the past thirty years or so has taught us anything, it is that tidy narrative arcs and precise ideological labels obscure as much as they illuminate, and that the lives of individual revolutionaries were typically shaped by a mixture of ideological and emotional commitment filtered through a web of personal experiences and aspirations.

I have pursued Volkhovskii for many years in archives and libraries across Europe and North America, and although I could not obtain all the documents from the archives that I would like to have seen, I am confident that the material I was unable to consult following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 would not change the picture that emerges in the following pages. It will hopefully, in future, be possible once again for foreign scholars to work in Russia but, given the uncertainties prevailing at the time of writing, it seemed sensible to complete the book now rather than delay its publication still further. It has indeed already been far too long in the making (although that has had the benefit of allowing me to read much excellent recent work by scholars both in Russia and the West). Many years of involvement in university management slowed the pace of research. So too did the demands of other projects. The coronavirus pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine greatly complicated the collection of material in Moscow and Kyiv. A series of family bereavements diverted attention away from what is, when all is said and done, the less important business of academic writing. The notes and bibliography will hopefully give some sense of the scale of my debt to the research of fellow scholars from around the world. Writing a biography requires engagement with a vast historical landscape and weighty scholarly debates, and for much of the time the biographer must rely on the labours of others, who have often devoted their careers to studying developments that represent just a fleeting moment in the life of the individual under review. I have tried to keep the text as readable as possible by dealing lightly with discussions about such perennial questions as the character of Russian populism and the effectiveness of revolutionary parties in undermining the tsarist regime during its final decades. Scholars with a particular interest in these and other topics will hopefully be able to use the notes to understand how Volkhovskii can be situated within these debates. I have also tried where possible to make use of Soviet and post-Soviet literature that has not always received sufficient acknowledgement by historians in Western Europe and North America. Scholarship is always of necessity a transnational project, even if it can never altogether break free from pressures that undermine efforts to build closer academic ties across political borders.

It is perhaps worth noting here in the light of recent events that Volkhovskii was in many ways a Ukrainian: born in Poltava; brought up in a multilingual milieu; convinced that ‘Little Russia’ was a place with its own identity and character. His ‘Ukrainophilism’ was closely bound up with a sense that national sentiment could be used as an agent for revolutionary change, although he was equally sceptical of ‘nationalism’, recognising how it could be used to cement existing hierarchies and corrupt new ones. There have been some efforts in recent years to claim Volkhovskii as a Ukrainian, which are not without merit, but Volkhovskii was, above all, a man committed to the struggle for freedom of all those living under the rule of the tsarist autocratic state. I have in the text typically used Russian names for individuals and places but have, where it seems more appropriate, included the Ukrainian spelling.

In writing this book I have incurred help from individuals too numerous to name in full. Professor Dominic Lieven has continued to provide wise counsel and support in the thirty-five years since he served as my PhD supervisor. Professor Simon Dixon and Professor David McDonald provided invaluable support in obtaining the grants and fellowships that made the research possible. Professor N. V. Zhiliakova, Dr Aleksandr Mazurov and Andrei Nesterov provided me with material that I could not obtain in the United Kingdom. I was fortunate enough to examine the PhD of Dr Lara Green, whose work has been invaluable in completing the book (Dr Green also kindly made available to me her notes on some archival collections that I had not myself seen for some years). Dr Robert Henderson provided me with helpful advice about archival material in Moscow. Professor Rebecca Beasley sent me proofs of her book on Anglo-Russian cultural relations at a time when the coronavirus pandemic made travel to libraries impossible (I should note that while the first draft of this book was complete before I read Professor Beasley’s book, it has been invaluable in helping to contextualise Volkhovskii’s literary activities). Dr Helen Grant was kind enough to answer some of my queries about the Garnett family. I have down the years benefitted greatly from conversations about Volkhovskii with many people including, among others, Professor Charlotte Alston, Dr Ben Phillips, and Dr Anat Vernitskii. I also need to thank the reviewers of the manuscript for their suggestions. Maryam Golubeva provided help with translations of some hard-to-decipher handwritten material. Dr Alessandra Tosi and her colleagues at Open Book Publishers, Adèle Kreager, Maria Eydmans, and Rosalyn Sword have been exemplary in their helpfulness and efficiency, and I am delighted to once again be associated with such an innovative organisation. I owe a debt of thanks to audiences at seminars where I have spoken about Volkhovskii in the UK and the United States. I must also extend huge thanks to colleagues from both Russia and Ukraine who have offered practical help, particularly during the final stages of this project, when a new and tragic smutnoe vremia (time of troubles) made further visits to both countries impossible. I hope one day to be able to return and thank you all in person.

I owe, too, an enormous debt to staff at archives and libraries around the world, above all at the two institutions which house the biggest collections of Volkhovskii’s papers, namely the Hoover Institution Library and Archives (Stanford University) and the Houghton Library (Harvard University). I also owe thanks to staff at other archives and libraries including the Bakhmeteff Archive of Russian and East European Culture (Columbia University); the British Library of Political and Economic Science (LSE) Archives and Special Collections; Gosudarstvennyi arkhiv Rossiiskoi Federatsii (Moscow); the International Institute of Social History (Amsterdam); the Leeds Russian Archive (Brotherton Library, University of Leeds); the Library of Congress Manuscript Division; the McCormick Library of Special Collections (Northwestern University); McGill University Library Rare Books and Special Collections; the National Archives (London); Newcastle University (Philip Robinson Library) Special Collections; Newnham College Cambridge Library; the New York Public Library (Special Collections); the Parliamentary Archives (UK); Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi arkhiv literatury i iskusstva (Moscow); and the Slavonic Library (National Library of Finland). The research for this project was made possible by generous financial support from the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, the British Academy (award SG2122\210709), and my home institution Lancaster University. Lancaster University also provided funding to support the open access publication of this book.

I owe as ever a great debt to my family, in particular Katie, for their support during the last few difficult years. This book is dedicated to my mother, Anne Hughes, and to the memory of my father, John Pryce Hughes, who sadly died before it was published.

Contents

Preface

1. Introduction

2. The Making of a Revolutionary

3. Prison, Poetry and Exile

4. Selling Revolution

5. Spies and Trials

6. Returning to the Revolutionary Fray

7. Final Years

8. Conclusion

Bibliography

Index

Everything passes away—suffering, pain, blood, hunger and pestilence. The sword will pass away too, but the stars will still remain when the shadows of our presence and our deeds have vanished from the earth. There is no man who does not know that. Why, then, will we not turn our eyes to the stars? Why?

1

Mikhail Bulgakov, The White Guard

Everything is what it is: liberty is liberty, not equality or fairness or justice or culture, or human happiness or a quiet conscience.

Isaiah Berlin, Two Concepts of Liberty2

Man is a torch, then ashes soon,

May and June, then dead December,

Dead December, then again June.

Who shall end my dream’s confusion?

Life is a loom, weaving illusion...

Vachel Lindsay, ‘The Chinese Nightingale3’

1 Mikhail Bulgakov, The White Guard, trans. Michael Glenny (London: Fontana, 1979), 270.

2 Isaiah Berlin, Two Concepts of Liberty. An Inaugural Lecture Delivered before the University of Oxford on 31 October 1958 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1958).

3 Vachel Lindsay, The Chinese Nightingale and Other Poems (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1922).

1. Introduction

©2024 Michael Hughes, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0385.01

The Russian political exile Feliks Volkhovskii died in London at the start of August 1914, at the age of sixty-eight, as Europe slid into the maelstrom of war. The outbreak of hostilities represented a defeat for a liberal peace movement that held military conflict to be morally unconscionable and economically destructive.1 It also revealed the impotence of a socialist internationalism that believed war was the consequence of imperial rivalry for markets in which the workers had no stake.2 There is no record of how Volkhovskii reacted to the chaos of the July Crisis. His health was poor, and he probably knew little of events taking place beyond the cloistered world of his flat in West London, but if he had known then he would surely have been distraught. Volkhovskii had for many years been one of the most prominent voices in the Russian Socialist Revolutionary Party warning about the threat posed by ‘militarism’ both to European peace and the cause of revolution in the Russian Empire.

Volkhovskii first arrived in London in 1890, following a dramatic flight from Siberia, where he spent more than a decade in administrative exile for involvement in a society that planned ‘at a more or less remote time in the future, to overthrow the existing form of government’.3 Over the next few years, he became a public figure in Britain, writing and lecturing at length about the harsh treatment meted out to those in Russia who opposed the tsarist government. Along with several other Russian émigrés in London, including Sergei Stepniak-Kravchinskii and Nikolai Chaikovskii, he worked closely with members of the Society of Friends of Russian Freedom producing the newspaper Free Russia. Volkhovskii also established friendships with several Britons who played an important role in fostering interest in Russian literature among their compatriots, most notably Edward Garnett and his wife Constance, whose translations of novelists including Leo Tolstoi and Fedor Dostoevskii helped to fuel the Russia craze in Britain during the decades before the First World War.4

Volkhovskii made a powerful impression on many of those he met in Britain during the 1890s. Although he never became such a well-known figure as Sergei Stepniak or Petr Kropotkin, he contributed regularly to British newspapers and journals, while his colourful lectures about his time in Russia attracted large audiences up and down the country. His name had already become familiar to many of those interested in Russian affairs when he was still in Siberian exile, thanks to the work of the American writer George Kennan, who first met Volkhovskii when he travelled through the region in the mid-1880s collecting material for a series of articles in The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine. Kennan told his readers in 1888 that

To me perhaps the most attractive and sympathetic of the Tomsk exiles was the Russian author Felix Volkhofski … He was about thirty-eight years of age at the time I made his acquaintance, and was a man of cultivated mind, warm heart, and high aspirations … His health had been shattered by long imprisonment in the fortress of Petropavlovsk; his hair was prematurely gray, and when his face was in repose there seemed to be an expression of profound melancholy in his dark brown eyes.

5

Following his flight from Siberia to London, via North America, Volkhovskii worked closely with Kennan in the campaign to promote Western sympathy for the opposition movement in Russia, and while the two men often disagreed on questions of tactics, the American never lost his affection for his old friend. A few months after Volkhovskii’s death, Kennan wrote that he had throughout his life shown ‘a fortitude in suffering and indomitable courage in adversity [that] put to shame the weakness of the faint-hearted … and compel even the cynic and the pessimist to admit that man, at his best, is bigger perhaps than anything that can happen to him’.6

Kennan’s hagiographic description was echoed by many others who knew Volkhovskii during his years in emigration. The journalist and writer G. H. Perris, who worked closely with Volkhovskii in London, described him as ‘the poet and the statesman of revolutionary propaganda’ whose ‘fiery spirit’ never flagged despite years of imprisonment and exile.7 Sympathetic obituaries in the British press following his death told readers how Volkhovskii had lived ‘a life truly great’ that illustrated ‘the grandeur of fraternity among the toilers of the earth’.8 J. F. Green, who for a time co-edited Free Russia with Volkhovskii, recalled his old friend as ‘a charming companion’ of ‘wide culture’.9 The Executive Committee of the Society of Friends of Russian Freedom praised the ‘sacrifices’ he had made for his country.10

Kennan’s original articles in Century Magazine used an almost martyrological language to represent Volkhovskii as a heroic figure who embodied the suffering of critics who dared to oppose the Russian autocratic government. Many of those who subsequently wrote about Volkhovskii echoed this trope by making much of the personal tragedies he had faced while still living in Russia. His first wife died in Italy when he was in prison in St Petersburg awaiting trial. His second wife killed herself after struggling with the hardships of Siberian exile. He lost two children in infancy. Volkhovskii himself seldom referred to these personal tragedies after his flight from Russia, but he was adept during his first ten years in Britain at fashioning a persona that dramatised and embodied the anguish endured by many critics of the tsarist regime. He sometimes imitated Kennan by lecturing to audiences dressed in the clothes and chains of a Russian convict (Volkhovskii himself had in fact worn neither while in Siberia). He was also skilled at behaving in ways that dovetailed with the expectations of the social and literary circles in which he moved, presenting himself as an exotic representative of an intriguingly alien country, yet one who could easily accommodate himself within the orbit of Western culture and values. And, in his articles and lectures, he discussed Russian affairs in general—and the Russian revolutionary movement in particular—in ways that were designed to reassure his audience that the values espoused by Russian revolutionaries like himself were consonant with those held by respectable liberals and moderate socialists in countries such as Britain.

There was nevertheless something paradoxical about the efforts made by Volkhovskii and some other political émigrés in Britain to defend a Russian revolutionary movement whose members were often committed to tactics and values profoundly at odds with the political and cultural mores of late Victorian and Edwardian Britain. Volkhovskii himself was for the most part ready to endorse the use of terrorism in Russia, both as a natural response to the brutality of the tsarist state and as an ethical means of bringing about political change. He was also a socialist who believed that, in Russia at least, the main value of such liberal appurtenances as universal suffrage and freedom of speech lay in their role in facilitating the struggle for a new social and economic order. Many Britons who sympathised with the struggle against tsarism by contrast viewed the Russian revolutionary movement through a prism shaped by a fusion of the Nonconformist Conscience and hazy memories of a previous generation of European revolutionaries like Lajos Kossuth and Giuseppe Mazzini. It was at best a partial understanding of a complex reality.

There is in fact a real danger of reducing Volkhovskii’s career to his role as an intermediary between the Russian revolutionary movement and its British supporters in the years after 1890 (a theme that dominates the way he is discussed in much of the existing literature). The leader of the Socialist Revolutionaries, Viktor Chernov, wrote in his memoirs that ‘the life of Feliks Volkhovskii is a history of the Russian revolutionary movement, of which he remained a true and faithful servant his whole life’ [italics added].11 Vera Figner, who played a leading role in the Narodnaia volia (People’s Will) organisation that assassinated Tsar Aleksandr II in 1881, agreed that ‘the whole of his [Volkhovskii’s] … life was devoted to the revolutionary cause’.12 The focus on Volkhovskii’s long and varied revolutionary career was echoed in the obituaries that appeared in Russia following his death. Nikolai Chaikovskii recalled that when he first met Volkhovskii in the early 1870s, his new acquaintance was already a veteran of the revolutionary movement, who had endured two terms of imprisonment.13 An obituary published a few months later in Mysl’ focused by contrast on Volkhovskii’s work in the final decade of his life, when he played an important role in the Socialist Revolutionary Party, editing many of its publications, and serving on the Foreign Committee that provided material support to revolutionaries organising uprisings across Russia.14 Both obituaries said much less than the British press about Volkhovskii’s role editing Free Russia and his work with members of the Society of Friends of Russian Freedom.15

One of the main aims of this book is indeed to gently ‘shrink’ the Volkhovskii familiar to many of his British friends and allies, and instead give more attention to placing him within the development of the Russianrevolutionary movement. A good deal of valuable work has been published in recent years discussing Russian revolutionary communities abroad and the integration of Russian revolutionaries within broader transnational revolutionary networks.16 The limited scholarly attention given to Volkhovskii has similarly focused on his role in shaping American and European attitudes towards Russia in the 1890s and early 1900s, although he has too often been seen primarily as a sidekick to Stepniak, lacking the glamour and brilliance of his better-known friend.17 Much less has been written—particularly in English—about the other parts of his life.18 Volkhovskii was, as Figner and Chernov recognised, a living embodiment of the development of the Russian revolutionary movement. He came of age in the 1860s under the influence of the revolutionary scientism of ‘nihilists’ like Nikolai Chernyshevskii and Dmitrii Pisarev. He was imprisoned in 1869 on suspicion of being involved in the network of groups that surrounded Sergei Nechaev, the self-fantasising enfant terrible of the Russian revolutionary movement, whose murder of one of his followers was immortalised by Dostoevskii in his novel Besy (The Devils). Volkhovskii subsequently became a prominent figure in the Chaikovskii milieu that coalesced in the early 1870s, paving the way for the ‘Going to the People’ movement of 1874, when thousands of young Russians fanned out into the Russian countryside in an effort to draw closer to the people, although he was himself always sceptical of those populists (narodniki) who believed that some elusive quasi-mystical wisdom was to be found among the ordinary Russian peasants. Following his exile to Siberia, Volkhovskii largely reinvented himself, playing a significant role in the cultural life of Tomsk, writing numerous short stories and poems, as well as becoming the most prolific contributor to the newly established paper Sibirskaia gazeta (Siberian Gazette).

Following his flight from Siberia and arrival in London in the summer of 1890, where he became a central figure in the international campaign against tsarist Russia, Volkhovskii continued to play a significant role supporting the development of the Russian revolutionary movement. He was a key figure in the Russian Free Press Fund, which printed radical literature for distribution in Russia, and joined his old friend Stepniak in efforts to overcome the divisions that characterised the Russian revolutionary movement. The two men also sought to build closer links with Russian liberals, a tactic viewed with scepticism by revolutionary luminaries like Petr Lavrov and Georgii Plekhanov, who feared that such cooperation would weaken rather than strengthen the opposition to tsarism. In the chaotic aftermath of the 1905 Revolution, Volkhovskii returned for a time to Russia, where he played a role producing propaganda designed to encourage mutiny in the Russian army and navy, before fleeing the country once again to avoid arrest. In the final years of his life, he served as a regular delegate for the Socialist Revolutionaries at conferences of the Second International. He was, to put it flippantly, something of a revolutionary ‘Forrest Gump’ whose life can provide a segue into the development of the Russian revolutionary movement.19

Vera Figner once suggested that there was ‘almost no material’ on Volkhovskii in the literature describing the history of the Russian revolutionary movement.20 Volkhovskii’s name in fact appears quite regularly in the memoirs published in such journals as Byloe (The Past)and Katorga i ssylka (Penal Servitude and Exile), for he was a familiar figure to several generations of revolutionaries, ranging from the ‘new people’ of the 1860s through to the neo-narodniki of the early twentieth century. He was himself a prolific writer of poetry, short stories, literary criticism and polemical journalism. Yet the archival trail is surprisingly thin on material casting light on his ideas and activities. Volkhovskii was a keen correspondent, but while he kept many of the letters he received, only a small number of those he wrote have been preserved. His diaries are episodic and contain little of substance. The records of the Okhrana and its predecessors contain some material relating to surveillance and interrogation, but they seldom reveal much substance about Volkhovskii’s networks and activities.21 Some useful documents can be found in the archives of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, but even there he remains an elusive figure. Volkhovskii wrote several autobiographical pieces towards the end of his life, both for Russian and Western audiences, but while such accounts are valuable, they need to be read with caution given his penchant for turning his experiences into propaganda. His biography must instead be assembled from sources scattered around the world in archives and long-forgotten publications.

The problem in reconstructing the ‘life and times’ of Volkhovskii is not, though, simply one of source material. It is also the challenge of locating him within a fast-moving and complex landscape, in which he was sometimes a significant figure, but seldom a pivotal one. Volkhovskii was a highly intelligent man, who had little interest in dogma, and was throughout his life impatient with the ideological squabbles that so often characterised the revolutionary movement. His own outlook was characterised above all by his loathing of the tsarist social and political order and his commitment to ending the exploitation of the Russian narod, the ‘ordinary’ Russian people, idealised and mythologised by generations of educated Russians in ways that were often fantastic and naïve.22 These two instincts—and they were instincts rather than highly articulated principles—underpinned his ideas and actions for half a century. Yet it was precisely Volkhovskii’s impatience with ideology that makes it difficult to delineate his long career in terms of the vocabulary typically used to explore patterns of opposition to tsarism: nihilist, radical, revolutionary, populist, liberal and the like.

This should not come as any surprise. The literature on the Russian revolutionary movement that has appeared over the past twenty-five years or so has taken seriously the lived experience of its participants. The opening up of archives has combined with new ways of thinking about history to allow a richer exploration than one that focuses simply on ideas and organisations. Biography has once again become recognised as a valuable way of understanding the past, not so much for restoring agency to the individual, but because it shows the uncertain and contradictory motives that influence the actions of both the celebrated and the obscure.23 Detailed discussion about the ideology espoused by members of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, for example, seems less compelling when research into the situation on the ground shows patterns of complexity and diversity that do not fit easily into neat categories.24 Even such seminal developments as the split between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks now appear more fluid and uncertain than they once did. The history of opposition to tsarism was characterised by an ever-changing kaleidoscope of individuals and organisations with more-or-less clearly held objectives and ideologies. Too close a focus on ideas and plans runs the risk of assuming that members of the radical opposition thought and acted in line with well-defined ideological principles and a clear sense of tactics. Yet ignoring such things altogether runs the risk of missing how the language and practice of opponents of the tsarist regime were saturated by a conviction that any successful effort to bring about change had to be rooted in a coherent analysis of the possibilities and limitations imposed by Russia’s historical situation.

It is in the light of such things, to return to a previous point, that the value of a biography of Feliks Volkhovskii partly rests. It is not only that it can provide a fuller picture of his role within the revolutionary milieu, although that is certainly one of the benefits, given that he has been largely overlooked by historians. Nor is it simply that his career can serve as a prism through which to view wider patterns in the development of opposition to tsarism. A study of Volkhovskii’s biography can also illuminate the many ways that the Russian revolutionary movement can be explored: socially, culturally, intellectually and organisationally. As the following chapters will show, Volkhovskii was in many ways a ‘typical’ representative of the Russian intelligentsia, who came to maturity in the 1860s, and dedicated the rest of his life to undermining the tsarist state and the social and economic order it symbolised and protected. At the same time, though, his life—like all lives—was governed by unpredictable contingencies and the need to respond to the countless changes that took place in Russia during the fifty years before the First World War.

It is this that makes Volkhovskii’s career so difficult to describe in terms of a vocabulary that is itself often inadequate or confused. It is hardly a concession to the wilder epistemological shores of postmodernism to recognise that social and political labels have uncertain and shifting meanings. The only practical response is to engage in the kind of linguistic pragmatism that is the staple of most historians (even if they are sometimes reluctant to admit it). The situation can perhaps be best illustrated by looking at a few examples. While the literature on the Russian intelligentsia is immense, and perhaps still pervaded by a sense that the holy grail of a precise meaning remains elusive, there is something close to a consensus that it constituted a distinctive social-cultural-psychological milieu, characterised both by its alienation from the dominant mores of tsarist Russia and by a moral commitment to promoting the well-being of the victims of the social and political status quo.25 The most astute work on the subject has often focused less on the challenge of defining the intelligentsia in terms of its supposedly enduring abstract features and more on exploring the factors that shaped its evolution in a specific historical situation, often through the prism of particular individuals. The character of the intelligentsia was not fixed over the course of half a century. Nor was its development uniform. By examining individual lives, it becomes easier to understand the Russian intelligentsia in all its heterogeneity, recognising that any attempt to reduce it to a specific set of features is doomed to fail. Volkhovskii himself was, by any understanding of the term, an intelligent whose efforts to bring about revolution shifted over time in response to changing circumstances.

A similar point can be made when addressing the question of whether Volkhovskii was a narodnik (or ‘populist’ to use the English word most often used as a translation). The term itself has long proved elusive, generating extensive academic discussion among scholars about its meaning and relationship to broader European understandings of populism.26 While Volkhovskii had little interest in ideological questions, he was not really a narodnik in the sense suggested by Richard Pipes, who argued in a celebrated article that the term should be limited to a small number of radicals who believed that they should seek to learn from the narod rather than lead them ‘in the name of abstract, bookish, imported ideas’.27 Nor was he much interested in the extensive debates that took place about how the tsarist regime needed to be overthrown to forestall the disintegration of the peasant commune in the face of the development of capitalism (fears that have for some historians come to define narodnichestvo, at least before the 1880s, as a form of anti-capitalist radicalism).28 And, more than twenty years later, Volkhovskii contributed little to the earnest discussions within the Socialist Revolutionary Party about questions of post-revolutionary land tenure that so preoccupied Viktor Chernov and many other Party leaders.

Volkhovskii, indeed, wrote almost nothing about the peasant commune and surprisingly little about the Russian peasantry. And yet, in his personal foundation myth, he described how it was the harsh treatment of Russian serfs which he witnessed as a child that led him to question the legitimacy of the existing order. His first major ‘revolutionary’ activity was planning the clandestine circulation of literature in the Russian countryside, as a means of fostering popular enlightenment through building closer links between the peasantry and sympathetic members of the intelligentsia. In many of his writings about literature and theatre in the 1880s, Volkhovskii called for the publication of books and plays crafted to illuminate the culture of the Russian narod, while many of the short stories he wrote throughout his life echoed motifs from traditional Russian folktales (more often than not with a distinct radical twist). There is, in short, no neat answer as to whether Volkhovskii was or was not a narodnik given that it is a yardstick that lacks precise meaning or definition. What remains important is that his attitude towards social and political questions was shaped by the sense, so characteristic of the Russian intelligentsia of the second half of the nineteenth century, that there was a moral imperative on all those who recognised the wretched condition of the Russian narod to do everything in their power to ameliorate it. His ideas and instincts—not to mention his actions—clearly place him within the network of individuals and groups that are conventionally assumed to fall within the broad framework of narodnichestvo. And, equally clearly, they distance him from the tradition of Marxism–Leninism that triumphed in October 1917, three years after Volkhovskii’s death.

A rather different issue is whether Volkhovskii was a revolutionary as opposed to a radical or even a liberal. Much of the ambiguity about Volkhovskii’s status as a revolutionary stemmed from his ideological flexibility and readiness to work with all those seeking to bring about change in Russia. It was noted earlier that some leading figures in the Russian revolutionary movement, like Lavrov, thought that he was too focused on building bridges with Russian and Western liberals, yet the tsarist authorities always recognised Volkhovskii as someone who could pose a serious threat both before he left Russia and later in emigration. Nor did he himself shrink from the label revolutionary, even if when writing for a Western audience he typically emphasised how revolution represented a natural choice in the face of repression, rather than a commitment to radical social and economic change. Volkhovskii never had much interest in Russian liberalism as a distinct intellectual tradition, but he was throughout his career willing to work with those who sat more easily within the confines of (semi-)permitted dissent, whether in Odessa (Ukr. Odesa) in the 1870s or London in the 1890s. While some of his critics saw such a position as evidence of a lack of ideological rigour and revolutionary zeal, it was in large part a reflection of Volkhovskii’s pragmatism, and his determination to find the most effective way of undermining the tsarist regime.

All this, in a sense, simply underscores a truth familiar to any biographer: that it is possible in most lives to discern distinct patterns that nevertheless ebb and flow in response to changes and circumstances that disrupt even the most definite narrative arc. Karl Marx was prescient when he observed that ‘Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please’. So, too, is there much truth in the quotation, often attributed to Churchill, that ‘when the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do?’ The development of the Russian revolutionary movement was for fifty years or more characterised by a struggle between what some nineteenth-century thinkers called necessity and freedom. Or, to put it rather differently, the challenge facing many of its leading representatives lay in reconciling a view of the world influenced by clear ideological preconceptions with the need to respond to ever-changing but nevertheless still constraining circumstances.

Even the most determined of revolutionaries could not avoid altogether the need to adopt new tactics and ideas in response to events. Vladimir Lenin was once seen by many scholars as an ideologue who bent the course of Russian history by his titanic will. Yet, more recent biographies have rightly recognised how he often responded to events in a pragmatic way to advance his long-term objectives.29 The most interesting questions focus on the extent to which his short-term manoeuvrings became the substance of his revolutionary work. In other words, was Lenin’s use of Marxist language simply a cloak for his all-consuming emphasis on making revolution, or was it rather the framework that shaped his activities, while leaving sufficient room to use his agency to respond to circumstances? Common sense suggests there was an element of both. And common sense suggests, too, that the same was true of many other revolutionaries who had to reconcile their intellectual convictions with the stubborn material of history. Volkhovskii’s commitment to revolution was the product, above all, of a visceral loathing of the tsarist state and a determination to promote the welfare of the Russian people. His focus was less on doctrine and more on action—weakening the tsarist state at specific moments in time—in order to expand the potential for developing practical ways of improving the material and cultural position of the narod.

It is this insight that frames the argument in the pages that follow. Chapter 2 and Chapter 3 examine Volkhovskii’s life in Russia before his flight to the west, tracing the genesis of his radical views, and setting them against the wider revolutionary drama, with its progression from the ‘nihilism’ of the 1860s, through the populism of the 1870s, and on to the bleak years of repression that followed the murder of Aleksandr II in 1881. Chapter 4 and Chapter 5 then explore Volkhovskii’s time in Britain in the 1890s, arguing that while he played an important role in mobilising international support for the victims of tsarist oppression, he also remained a significant figure in the broader revolutionary emigration through his role in the production and distribution of propaganda. Chapter 6 and Chapter 7 discuss the last fifteen years of Volkhovskii’s life, when he once again firmly established himself within the ambit of the Russian revolutionary movement, as opposed to being a political exile whose career was characterised primarily by his relations with foreign liberals and radicals. There is a sense in which Volkhovskii became increasingly ‘revolutionary’ during his last years, expressing more openly than before his support for the use of force to destroy the autocratic regime, and questioning the value of working with moderate opposition groups to bring about change. Whether this represented a definite change in his position, or rather the more forceful articulation of views long held, is perhaps a moot point.

Many of the themes that emerge in these chapters are touched on above: Volkhovskii’s general lack of interest in the details of ideological discussion; his focus on the narod, not as a repository of communal virtue, but rather as the victim of a harsh social and political order; his sometimes ambiguous attitude towards terrorism and political violence; his growing concern over the threat posed to peace by the forces of ‘militarism’; and, perhaps above all, his readiness to respond to circumstances in ways that could make him seem inconsistent but were often simply a reaction to the situation in which he found himself. Any biography of Volkhovskii also needs to capture other aspects of his life, not least his work as a poet and short story writer, along with his activities as a critic and translator. Nor were these simply ephemeral interests. Literary activity was central to the nineteenth-century Russian intelligentsia, in part because it provided a vehicle for expressing views and sentiments likely to face censorship if articulated in more purely political terms, and partly because culture itself was often seen as a kind of handmaiden to the revolutionary cause. Many of Volkhovskii’s short stories and poems were propagandistic in character, but he undoubtedly had real literary ability, as well as very significant talent as a critic. His work was the hallmark of a man who was for all his revolutionary passion something more than a revolutionary. And, as will be seen in the chapters that follow, while some of those who met Volkhovskii could find him domineering and impatient, many others considered him to be, in the words of ‘the grandmother of the revolution’, Ekaterina Breshko-Breshkovskaia, one of the ‘noblest hearts’ of the Russian revolutionary movement.30 What follows is above all a biography of Volkhovskii’s public life, but it tries too to capture at least a little of the elusive timbre of a man whose personality impressed so many of those he met as a model of integrity, and who faced the harsh vicissitudes of life with enormous courage and strength.

1 Among the large literature on the peace movement both in Britain and abroad before the First World War see, for example, Sandi E. Cooper, Patriotic Pacifism. Waging War on War in Europe, 1815–1914 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991); Paul Laity, The British Peace Movement, 1870–1914 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

2 For a useful overview of the genealogy of socialist internationalism before 1914, see Patrizia Dogliani, ‘The Fate of Socialist Internationalism’, in Glenda Sluga and Patricia Clavin (eds), Internationalisms: A Twentieth Century History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 38–60. James Joll, The Second International, 1889–1914 (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1955) remains a lively if dated account of the Second International.

3 George Kennan, Siberia and the Exile System, 2 vols (New York: Century Company, 1891), I, 333.

4 For an excellent account that examines how networks of Russian émigrés and British writers helped to fuel the Russia ‘craze’, see Rebecca Beasley, Russomania: Russian Culture and the Creation of British Modernism, 1881–1922 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020). Beasley’s monograph only appeared when the first draft of this book was completed but has proved invaluable in helping to contextualise Volkhovskii’s literary activities.

5 George Kennan, ‘Political Exiles and Common Criminals at Tomsk’, The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine (henceforth Century Magazine), 37, 1 (November 1888), 32–33.

6George Kennan, A Russian Comedy of Errorswith Other Stories and Sketches of Russian Life (New York: The Century Company, 1915), 139.

7G. H. Perris, Russia in Revolution (London: Chapman and Hall, 1905), 226.

8Daily Herald (6 August 1914).

9Justice (13 August 1914).

10Manchester Guardian (14 August 1914).

11 V. M. Chernov, Pered burei (Moscow: Direct Media, 2016), 203.

12 V. I. Figner, Posle Shlissel’burga (Moscow: Direct Media, 2016), 345.

13 N. V. Chaikovskii, Obituary of Volkhovskii, Golos minuvshago, 10 (1914), 231–35.

14 Ritina [I. I. Rakitnikova], Obituary of Volkhovskii, Mysl’, 40 (January 1915).

15 The same was true of the obituary by N. E. Kudrin that appeared in Russkoe bogatstvo, 9 (1914), 364–65, which focused overwhelmingly on Volkhovskii’s life before 1890 when he fled Russia.

16 The most important recent work taking this approach is without doubt Faith Hillis’s magisterial Utopia’s Discontents: Russian Émigrés and the Quest for Freedom, 1830s–1930s (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), which examines how Russian colonies abroad formed part of the broader Russian revolutionary movement, while also shaping and being shaped by their host communities.

17 Among the few publications in English devoted to Volkhovskii, see Donald Senese, ‘Felix Volkhovsky in London, 1890-1914’, in John Slatter (ed.), From the Other Shore: Russian Political Emigrants in Britain, 1870–1917 (London: Frank Cass, 1984), 67–78; Donald Senese, ‘Felix Volkhovskii in Ontario: Rallying Canada to the Revolution’, Canadian-American Slavic Studies, 24, 3 (1990), 295–310. A good deal of material can also be found in Donald Senese, S. M. Stepniak-Kravchinskii: The London Years (Newtonville, MA: Oriental Research Partners, 1987). Volkhovskii’s name has also started to occur more frequently in some recent work in English on the Russian revolutionary movement, not least because his papers often include valuable material about other better-known figures. See, for example, Lara Green, ‘Russian Revolutionary Terrorism, British Liberals, and the Problem of Empire (1884–1914)’, History of European Ideas, 46, 5 (2020), 633–48; Lynne Hartnett, ‘Relief and Revolution: Russian Émigrés’ Political Remittances and the Building of Political Transnationalism’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46, 6 (2020), 1040–56. Other literature touching on Volkhovskii’s time in emigration is discussed in later chapters.

18 For two recent exceptions, see the relevant sections of Ben Phillips, Siberian Exile and the Invention of Revolutionary Russia, 1825–1917: Exiles, Émigrés and the International Reception of Russian Radicalism (Abingdon: Routledge, 2022); Lara Green, ‘Russian Revolutionary Terrorism in Transnational Perspective: Representations and Networks, 1881–1926’ (PhD thesis, Northumbria University, 2019).

19 The reference is of course to the 1994 film directed by Robert Zemeckis, whose eponymous hero lives a life that intersects with some of the most dramatic events of the history of the United States in the second half of the twentieth century.

20 Figner, Posle Shlissel’burga, 346.

21 The Okhrana, or Department for the Preservation of Public Safety and Order, is often referred to as the tsarist secret police and regularly seen as the predecessor of the better-known secret agencies of the Soviet period. For a useful general history of the Okhrana, see Charles A. Ruud and Sergei A. Stepanov, Fontanka 16: The Tsar’s Secret Police (Montreal: McGill-Queens’s University Press, 1999).

22 The word narod was used by many members of the Russian intelligentsia to describe the ‘ordinary’ Russian people, typically the peasantry, although from the 1870s onwards it was increasingly used to describe urban workers as well. The character of the Russian narod—whether conservative or revolutionary—was at the heart of much social and political debate throughout the nineteenth century.

23 For a useful discussion of the scholarly nature of this development, see Hans Renders, Binne de Haan and Jonne Harmsma (eds), The Biographical Turn. Lives in History (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017). Many of the biographies cited in the chapters that follow have perhaps (and quite laudably) been inspired less by strong theoretical views and more by a recognition that studying the lives of individuals can help to understand the times they lived in.

24 The best general discussion in English of the Socialist Revolutionary Party before 1914, which captures its complexity and changing character, remains Manfred Hildermeier, The Russian Socialist Revolutionary Party Before the First World War (New York: St Martin’s Press, 2000).

25 Among the massive and often contradictory literature on the Russian intelligentsia in English see, for example, Isaiah Berlin, Russian Thinkers (London: Penguin, 1994); Martin Malia, ‘What Is the Intelligentsia?’, Daedalus, 89, 3 (1960), 441–58; Laurie Manchester, Holy Fathers, Secular Sons: Clergy, Intelligentsia and the Modern Self in Revolutionary Russia (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2008); Vladimir C. Nahirny, The Russian Intelligentsia: From Torment to Silence (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books, 1983); Philip Pomper, The Russian Revolutionary Intelligentsia (Wheeling, IL: H. Davidson, 1993); Marc Raeff, Origins of the Russian Intelligentsia. The Eighteenth-Century Nobility (New York: Harcourt Brace and World, 1966); Nicholas Riasanovsky, A Parting of Ways: Government and the Educated Public in Russia, 1801–1855 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976).

26 See, for example, the important collection edited by Ghita Ionescu and Ernest Gellner, Populism: Its Meaning and National Characteristics (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1969). The character of Russian populism and its treatment in the scholarly literature is discussed in more detail in Chapter 2.

27Richard Pipes, ‘Narodnichestvo: A Semantic Inquiry’, Slavic Review, 23, 3 (1964), 441–58 (445).

28 For an interpretation of Russian populism along these lines, see Andrzej Walicki, The Controversy over Capitalism: Studies in the Social Philosophy of the Russian Populists (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969).

29 For a lively biography of Lenin that firmly eschews a teleological approach in favour of one that captures his uncertainties and contradictions, see Robert Service, Lenin: A Biography (London: Pan Macmillan, 2010).

30 Alice Stone Blackwell (ed.), The Little Grandmother of the Russian Revolution. Reminiscences and Letters of Catherine Breshkovsky (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1918), 282.

2. The Making of a Revolutionary

©2024 Michael Hughes, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0385.02

Feliks Vadimovich Volkhovskii was born in July 1846 in Poltava, then a city of some 25,000 people, situated around five hundred miles south of Moscow in modern-day Ukraine.1 His father Vadim Petrovich Volkhovskii had served as an artillery officer before subsequently taking up a post in the Civil Service as a Collegiate Assessor. The rank was a comparatively modest one. A Collegiate Assessor was only marginally superior to a Titular Councillor, the rank held by Akakii Akakievich Bashmachkin, the downtrodden ‘hero’ of Nikolai Gogol’s short story ‘Shinel’’(‘The Overcoat’), who spends his evenings copying official documents by candlelight in a shabby attic room.2Vadim Petrovich’s situation was somewhat less parlous. He was the eldest of eight children born to Petr Grigor'evich Volkhovskii, a major in the Corps of Gendarmes, whose work required him to travel regularly across the empire. Vadim and his seven younger siblings spent most of their time on their mother’s small estate of Chepurkivka in the north-west of Poltava province. The family was far from wealthy, and although Vadim Petrovich’s childhood passed in modest comfort, he knew from a young age that he would have to earn his own living.

Vadim’s father Petr Grigor'evich himself retired from the Corps of Gendarmes in 1839, living for a while at Chepurkivka, before seeking a new position to improve his family’s finances. He found work managing factories in Perm province, but his new career was cut short when he fell from a horse, suffering a concussion that caused long-term damage to his memory. In the years that followed, he lived with his brother Stepan Grigor'evich, who later served as Governor of Samara Province, before the fortuitous death of a relative meant that Petr inherited the estate of Moisevka (Ukr. Moisivka) in Poltava Province (his brothers renounced their share of the estate leaving him in sole possession). The Moisevka estate was a substantial one consisting of 300 male peasants and more than 2,000 hectares of land.3 It had acquired some fame in the early 1800s for the lavish balls hosted there by one Petr Stepanovich Volkhovskii and his wife Tatiana (it was Tatiana who left the estate to Petr Grigor'evich and his brothers since she had no children of her own). The main house was built in an elaborate French style, surrounded by acres of parkland, complete with gazebos and fountains. Some visitors spoke of it in rather exaggerated terms as a veritable ‘Versailles’. A church was added in 1808 (which stands to this day).

The parties held by Petr and Tatiana Volkhovskii attracted the attention of the authorities on occasion—not least in the revolutionary year of 1848—when a number of guests belonging to the facetiously-named Obshchestvo mochemordiia (Society of Boozers) attended a party at the house where they gave a toast to the French Republic.4Moisevka was also for a time a notable centre of culture, attracting writers and artists including the poet Taras Shevchenko, whose work shaped the growth of a Ukrainian national consciousness during the 1840s and 1850s (a portrait of Petr Stepanovich and his wife painted by Shevchenko hung for many years on the walls of the manor house).5 By the time Petr Grigor'evich inherited the estate in the early 1850s, though, the house was very run down.6 His grandson Feliks later recalled that most of the rooms were shut up and unheated. The mirrors hanging on the walls were cracked and the portraits of half-forgotten ancestors covered with dust. The garden and park were unkempt and returning to wilderness. Volkhovskii had few happy memories of the time he spent at Moisevka as a young boy.

Volkhovskii wrote little about his early life, although on more than one occasion he described how he came to be christened with the distinctively un-Russian name of Feliks. He was throughout his life close to his mother, Ekaterina Matveeva (née Samotsvit), the daughter of a Polish mother and a Ukrainian-Russian father, who lived in the town of Novograd-Volynskii (Ukr. Zviahel) 150 miles west of Kyiv. When he was older, some of those who met Volkhovskii assumed from his name that he was a Polish Catholic, but he was baptised into the Russian Orthodox Church. His mother, who had previously lost two boys and a girl in infancy, vowed that her next child would be christened after the saint whose name-day was celebrated on the day the baby was born. According to her son, writing many years later, a priest in Poltava helpfully pointed out that the full Church calendar for the date of his birth included a reference to Feliks (one of the early popes). Father Ivan told the baby’s parents that they should have no qualms about naming a child after a pope who held office before the great schism between the Orthodox and Catholic churches. He also suggested that since Feliks was derived from the Latin felicitas—happiness—it was particularly suitable as the given name for the first child of his parents to survive beyond a few days.7

Although Feliks was born in the town of Poltava, he moved as a very young child to the family home of his mother in Novograd-Volynskii. Vadim does not seem to have joined his wife and child there, possibly because he was still in the army, although there are hints in Volkhovskii’s scattered reminiscences that his parents’ marriage was not a particularly happy one. Feliks was certainly closer to his mother, who in later years provided what support she could to her son during his time in prison, and later accompanied him to exile in Siberia where she died as a result of the harsh living conditions.8Ekaterina Matveeva had married Vadim Petrovich when she was only sixteen or seventeen, following a somewhat perfunctory education, although she subsequently immersed herself in the books of a medical student who lived for a time with the family (which among other things had the unfortunate side effect of turning her into a hypochondriac). She was in her son’s later estimation ‘naturally timid but extraordinarily kind-hearted’. Feliks also noted that his mother was by instinct ‘impulsive’ but disciplined enough to learn French and become a good housekeeper.9

Feliks had warm memories of his early years spent living with his mother’s family in Novograd-Volynskii where he stayed until he was seven or eight. In an article published more than fifty years later, in the journal Sovremennik (The Contemporary), he lovingly recalled his grandparents’ white one-storied house, complete with large windows that gave the building an open and welcoming appearance. Volkhovskii’s positive memories were doubtless coloured by his much bleaker experiences a few years later when living with his paternal grandfather at Moisevka, but there was genuine warmth in his recollection of the ‘bright and friendly’ life that characterised the Samotsvit household. He remembered the household as a ‘nest’ (gnezdo), a word he doubtless chose for its echo of Ivan Turgenev’s novel Dvorianskoe gnezdo (lit. Noble Nest), which had first appeared just a few years after Feliks left Novgorod-Volynskii for Moisevka.10

The Samotsvit household was headed by Feliks’ maternal grandfather, Matvei Mikhailovich, who had as a young soldier fought against the Napoleonic armies advancing on Moscow. Matvei was seriously wounded in the leg, an injury from which he never fully recovered, although Feliks remembered him many years later as a vigorous man ‘who did not give the impression of being an invalid’.11 His role as head of the household was nevertheless largely eclipsed by his wife Viktoriia Ivanovna, who also directed life on the family’s small country estate, which supplied the Samotsvits with eggs, meat and vegetables. The relationship of the elderly couple was a close one (‘two boots made from a single block’ in the words of their grandson). They surrounded themselves with numerous relatives who formed part of a large extended family. Several unmarried women—sisters and daughters of the old couple—lived in the house and contributed to the various tasks of household management. An unmarried son occupied a nearby flat and often called in for dinner. The picture of life at Novograd-Volynskii painted by Volkhovskii was one of a self-contained world that seemed impervious to the tribulations of life beyond the white-washed walls of the family ‘nest’.

Such tight-knit families were a familiar presence in nineteenth-century Russian literature in stories like Gogol’s ‘