7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Open Book Publishers

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

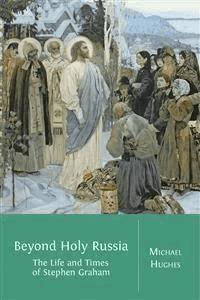

This biography examines the long life of the traveller and author Stephen Graham. Graham walked across large parts of the Tsarist Empire in the years before 1917, describing his adventures in a series of books and articles that helped to shape attitudes towards Russia in Britain and the United States. In later years he travelled widely across Europe and North America, meeting some of the best known writers of the twentieth century, including H.G.Wells and Ernest Hemingway. Graham also wrote numerous novels and biographies that won him a wide readership on both sides of the Atlantic. This book traces Graham’s career as a world traveller, and provides a rich portrait of English, Russian and American literary life in the first half of the twentieth century. It also examines how many aspects of his life and writing coincide with contemporary concerns, including the development of New Age spirituality and the rise of environmental awareness. Beyond Holy Russia is based on extensive research in archives of private papers in Britain and the USA and on the many works of Graham himself. The author describes with admirable tact and clarity Graham’s heterodox and convoluted spiritual quest. The result is a fascinating portrait of a man who was for many years a significant literary figure on both sides of the Atlantic.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

BEYOND HOLY RUSSIA

BEYOND HOLY RUSSIA

The Life and Times of Stephen Graham

Michael Hughes

www.openbookpublishers.com

© 2014 Michael Hughes

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information:

Hughes, Michael, Beyond Holy Russia: The Life and Times of Stephen Graham. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0040

Further details about CC BY licenses are available at

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders; any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher.

Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available from our website at:

http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781783740123

ISBN Paperback: 978-1-78374-012-3

ISBN Hardback: 978-1-78374-013-0

ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-78374-014-7

ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-78374-015-4

ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 978-1-78374-016-1

DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0040

Cover image: Mikhail Nesterov (1863-1942), Holy Russia, Russian Museum, St Petersburg. Wikimedia http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nesterov_SaintRussia.JPG

All paper used by Open Book Publishers is SFI (Sustainable Forestry Initiative), and PEFC (Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification Schemes) Certified.

Printed in the United Kingdom and United States by Lightning Source for Open Book Publishers

For my parents Anne and John Hughes

Contents

List of Illustrations

Epigraph

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. Chasing the Shadow

2. Searching for the Soul of Russia

3. The Slow Death of Holy Russia

4. The Pilgrim in Uniform

5. Searching for America

6. A Rising or Setting Sun?

7. New Horizons

8. A Time of Strife

9. The Pilgrim Reborn?

Final Thoughts

Bibliography

Index

List of Illustrations

Figure 1

Pen portrait of Stephen Graham by Vernon Hill, published in Stephen Graham, Changing Russia (London. John Lane, 1913), frontispiece.

p. 36

Figure 2

Photograph taken by Stephen Graham in the Terek Gorge of two Ingush women collecting water, published in Stephen Graham, A Vagabond in the Caucasus (London, John Lane, 1911), p. 140.

p. 39

Figure 3

Photograph taken by Stephen Graham at midnight of the inhabitants of a village near Archangel, published in Stephen Graham, Undiscovered Russia (London. John Lane, 1912), p. 24.

p. 48

Figure 4

Photograph taken by Stephen Graham of elderly Russian peasant woman on the banks of the Jordan, published by Stephen Graham, With the Russian Pilgrims to Jerusalem (London. Macmillan, 1913), p. 194.

p. 74

Figure 5

Two of the pictorial emblems appearing in Stephen Graham, Priest of the Ideal (London. Macmillan, 1917), pp. 151 and 165.

p. 115

Figure 6

Two of the illustrations by Vernon Hill in Stephen Graham, Tramping with a Poet in the Rockies (London. Macmillan, 1922), pp. 1 and 201.

p. 181

Figure 7

Press photograph of Vachel Lindsay and Stephen Graham (on the right) in 1921 (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vachel_Lindsay_with_Stephen_Gwynne.jpg) [NB in the original Stephen Graham is mistakenly identified as Stephen Gwynne].

p. 186

Figure 8

Stephen Graham in 1926 (photographer unknown). Courtesy National Portrait Gallery, © CC BY-NC-ND.

p. 219

Figure 9

Photograph of Stephen and Vera Graham on the 13 August 1957 (photographer unknown). Courtesy Private Collection.

p. 306

An Englishman (‘To Stephen Graham’)

I went an Englishman among the Russians,

Set out from Archangel and walked among them,

A hundred miles,

Another hundred miles,

A moujik among moujiks,

Dirty as earth is dirty.

And found them simple and devout and kind,

Met God among them in their houses –

And I returned to Englishmen, a Russian.

Witter Bynner, A Canticle of Pan

Умом Россию не понять,

Аршином общим не измерить.

У ней особенная стать,

В Россию можно только верить!

Fyodor Tiutchev

Acknowledgements

I have received a huge amount of help from around the world in writing this book. Financial support was provided at various points by the Harry Ransom Center (University of Texas), the British Academy, the University of Liverpool and the Scouloudi Foundation. I have benefitted from the generous help of archivists and librarians in more than a dozen institutions, and would like to acknowledge in particular the help of Bill Modrow and Burt Altman at the Strozier Library, Florida State University, along with Molly Schwartzburg and Bridget Gayle at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin. My work has also greatly benefitted from the feedback to papers I have presented in Athens GA, Cambridge, Canterbury, Liverpool, London, Moscow and Stockholm. I have received advice and help of various kinds from numerous other individuals including: Mike Bishop, Dr Phillip Ross Bullock, Professor Dennis Camp, Professor Anthony Cross (whose knowledge of Anglo-Russian cultural relations remains unrivalled), Professor Simon Dixon, Alan Freke, Lance Sergeant Kevin Gorman, Anil Gupta, Professor Marguerite Helmers, Dr Sam Johnson, Nicholas Lindsay, Javier Marias, Branco Omčikus, Marko Omčikus, Professor Predrag Palavestra, Dr Aleksandr Polunov, Professor Andrew Rigby, Paul Tomlinson and Mike Tyldesley (the latter representing the Mitrinović Foundation whose rich archive is housed at Bradford University). Sally Mills made generous use of her time and legal drafting skills to subject the manuscript to eagle-eyed scrutiny. Dr Alessandra Tosi at Open Book Publishers provided invaluable support and advice (and I am delighted to be associated with such an innovative enterprise). Many other people too numerous to mention have provided me with particular leads, and I hope they know how grateful I am to them. I am particularly grateful to those who have shared their memories of Graham with me. I would like to thank those who have given me permission to quote from material to which they own the copyright. Every effort has been made to trace holders of copyright material used in this book, and I would of course be happy to acknowledge any further copyright permissions in future editions. The publication of this book has been made possible by a generous grant from the Scouloudi Foundation in association with the Institute of Historical Research.

I owe as ever a huge debt to Katie who has yet again put up with a distracted husband whose mind must often have seen thousands of miles and many decades away. This book is dedicated with love and affection to my parents Anne and John Hughes.

Introduction

On 17 April 1975 a small congregation assembled on a drizzly grey day at St Margaret’s Church, in Central London, to attend a memorial service in honour of the writer Stephen Graham. Graham had died a few weeks earlier, just four days before his ninety-first birthday, and his passing had been marked by substantial obituaries in The Times and the Daily Telegraph. It is perhaps odd that they appeared at all. Both obituaries suggested that Graham would be best remembered for the books he had written before 1917, describing his time in pre-revolutionary Russia, which in the words of The Times made him “probably more responsible than anyone else in this country for the cult of Holy Russia and the idealization of the Russian peasantry that were beginning to make headway here before 1914”.1 Although the two obituary writers acknowledged that Graham had in later life written numerous novels and travel books, as well as a series of biographies and historical works, he seemed in death to be frozen as a thirty-year old figure tramping across the vast spaces of the Tsarist Empire, in search of a half-mythical world of icons and golden cupolas. Recollections of him were bound up with hazy memories of the Ballets Russes and the cult of Tolstoy, which transfixed a swathe of the British intelligentsia on the eve of the First World War, convincing numerous artists and writers that Russia could become an unlikely source of a cultural and spiritual renaissance destined to sweep the world. Graham had certainly spent much of his time as a young man trying to persuade readers that Russia possessed a richness of spirit that had long since vanished in the industrial west. The photographs that appeared of him in the British press, dressed in a peasant blouse with soulful face turned away from the camera, hinted at an elusive persona bearing words of truth from another world. But Graham had, even when writing about Russia, always been a more complex and multi-faceted figure than his obituaries acknowledged. Nor did he disappear from public view for the last sixty years of his life, instead retaining his popularity as a writer long after the Bolshevik seizure of power, which separated him forever from the country that dominated his imagination as a young man. Graham’s half-forgotten life consisted of much more than acting as a cheer-leader for the religious rituals of a sprawling autocratic empire falling apart in the face of its own contradictions.

Graham first visited Russia in 1906 and spent much of his time there over the next ten years, writing a total of eight books about the country, along with countless articles in publications ranging from Country Life to the Daily Mail. He did not invent the term ‘Holy Russia’, which had been in use in the British press since at least the 1880s, and was for centuries a staple of debate in Russia itself about the country’s imagined status as heir to the authentic tradition of Eastern Christianity. Nor was Graham alone in falling in love with a romanticised conception of the Russian Orthodox Church, one that revelled in the beauty of its architecture and liturgy, which seemed to hint at mysteries more profound than anything that could be sensed in the faintly suburban world of the Church of England. The Russian Church was for him, as for many other Britons, just one element in the picturesque tapestry of a land whose tantalising strangeness appeared as an intriguing enigma rather than a sinister threat. Russia was for Graham never just another country like France or Germany. It was instead a place that held out the hope of personal epiphany. He first travelled there in the years before the Great War as thousands of young hippies later went to Tibet and Nepal, seeking to overcome their sense of estrangement from the world into which they had been born. Perhaps all those who fall in love with a foreign country are to some extent prompted by dissatisfaction with their ordinary lives. Graham was no exception. Whilst it took him some time to realise it, he went to Russia as a pilgrim, searching for something that he could not name until he found it.

The Russia that Graham created for his readers in the years before 1917 was above all a kind of vast sacred space, a world whose people lived their lives attuned to metaphysical echoes that resonated through the landscape they inhabited. He certainly acknowledged that such awareness did not turn all Russians into saints – he was throughout his life powerfully attracted by Dostoevsky’s belief that it was through experience of sin that true humility was found. Nor did Graham deny that the vast social and economic changes taking place in Russia by the start of the twentieth century were threatening to erode its unique spiritual heritage. He was nevertheless convinced that there could be found in the mundane lives of the ordinary Russian peasantry a precious kernel, an intuitive understanding of wholeness that transcended the material conditions of everyday life, and brought together the here and now with a sense of the eternal. The simple practices of popular piety – the light in front of the ikon, the urge to go on pilgrimage – were evidence for Graham not of superstition but of a rich interior religious life. During his massive tramps across the Tsarist Empire, which took him from Archangel to the Caucasus and Warsaw to the Altai Mountains, he was himself a wanderer in search of meaning. When he travelled with hundreds of Russian pilgrims to Jerusalem in 1912, he was convinced there was a powerful symbolism in the fact that his companions were drawn from the ranks of the peasantry, noting in the book he wrote about his experiences that “it is with these simple people that I have been journeying”.2 A tall blonde man, often to be found with a pipe in his mouth, Graham must have cut a strange figure when dressed in the costume of those he travelled with. He was nevertheless always an acute observer of the people he met and the places he visited. Much of his popularity can be explained by his skill at providing readers with colourful portraits of life in far-away and exotic countries. His books about Russia were not, however, simply works of descriptive travel literature. They were instead suffused by meditations on the sense of unease that defined the atmosphere of life in Britain during the years leading up the cataclysm of the Great War. Graham unwittingly carried within himself many of the contradictions of the age into which he was born. An intensely individual man, who in his early years felt most at ease when walking alone through an empty landscape, he idealised the kind of community whose members would have frowned at his thoroughly modern desire to cross the world in search of new horizons and experiences.

There still remains the danger of reducing Graham’s long life to the ten years that he spent travelling to and from Russia. Within months of the February 1917 Revolution, he was conscripted into the Scots Guards, seeing action as a private soldier on the Western Front, before publishing a book about his experiences that was sufficiently critical to earn censure from Winston Churchill in the House of Commons. Over the next few years, Graham made several trips to America, walking through the South in 1919 in order to see at first hand the legacies of slavery, following up his trip two years later with a massive hike through the Rockies accompanied by the self-proclaimed “Prairie Troubador” Vachel Lindsay. A year later he spent six months exploring Mexico and the American south-west, mourning the death of his travelling companion Wilfrid Ewart in a freak accident, when the young novelist was shot through the eye on his hotel balcony by revellers firing into the air to celebrate New Year. In between these visits Graham established himself as something of a celebrity in New York, giving numerous lectures about his travels, and making friends amongst the city’s literary elite. His trips to the United States were interspersed with a visit to the bleak battlefields of France and a long journey to the capitals of the new states of central Europe created by the Treaty of Versailles.

Before the 1920s were out, Graham had made four more visits to New York, and travelled down the eastern frontier of the USSR, as well as spending time with the various Russian émigré communities that sprang up across Europe after 1917. He also found the energy to write a number of novels and sketches about life on the streets of London, as well as publishing an elaborate Credo, setting down a new spiritual vision for life in the post-war world. Graham subsequently spent much of the 1930s in Yugoslavia, walking and fishing in some of its remotest regions, as well as retreating to the mountains of northern Slovenia to write several more novels. He spent the Second World War back in London working for the BBC, possibly on the fringe of operations carried out by the Political Warfare Executive to spread black propaganda in occupied Europe, as well as editing a newsletter designed to act as a clearing house for information about the Orthodox Churches in war-time. Although his pace slowed down following the end of hostilities in 1945, he still found time to publish another three books, as well as producing manuscripts of several more that never appeared. By the time he died, Graham had published more than fifty books, including nine novels and five biographies, as well as numerous travel books and a three-hundred page autobiography. He also found time to write a number of short fantasies on subjects ranging from the ghost of Lord Kitchener through to an imaginary war in which French and Italian airplanes bombed the heart out of London.

Graham once observed that no biography could capture the truth of a life. There was certainly something unrevealing about his own autobiography, Part of the Wonderful Scene, even though it is full of anecdotes about the countless people he met throughout his long life. Whilst much of Graham’s writing was characterised by a confessional tone that made no effort to hide its author’s emotions and sensibilities, he was always adept at concealing his private life from his readers. Graham’s own background was decidedly un-Victorian, since his father abandoned his young family to set up a new home with a younger woman, whom he never married despite having two more children with her. Graham’s own first marriage disintegrated in the late 1920s, with considerable anguish on both sides, although the marriage itself only formally ended in 1956 with the death of his wife. He was himself from the 1930s closely involved with a young Serbian woman, whose family looked askance at their relationship, and the two of them effectively lived together as man and wife until they were free to marry after Graham was widowed. No mention of these events appears in any version of Graham’s autobiography (published or unpublished). This may in part simply have been the reticence of a decent man who had no desire to cause pain to anyone still alive. It may also have been that such irregularities sat uneasily with his conscience. They are in any case essentially private affairs, which appear in the following pages only to the extent that they cast light on the way that Graham’s work reflected the concerns and preoccupations of the man himself. No person is ever fortunate enough to be taken solely at their own evaluation. But nor should a study of the achievements of any writer or artist automatically feel the need to delve too deeply into the private life of friends and family, except where the material can help to illuminate the public world of books and paintings.

It is in any case no easy matter to recreate Graham’s life in full, even though this biography draws extensively on his private papers, which are scattered in numerous archives and libraries around the world. Most of his letters have been lost (particularly those written in Russian and Serbian). His surviving diaries and journals generally relate only to the years from 1918 to 1929. The manuscripts of his books give little away beyond showing that he was a remarkably fluent writer, who seldom felt the need to write detailed plans of his work before launching into a sea of prose. Graham’s private papers do nevertheless provide insights into his life and work that could never be culled from his written works alone. In some cases this concerns little more than matters of basic chronology. There are numerous errors in the dates of Graham’s own accounts of his travels, whilst he was in any case inclined to conflate different incidents and events in his books, redrawing their sequence in order to create a better story. His diaries and letters help to restore the jangled complexity that was sometimes missing from his published work. Graham’s papers also help to gently undermine some of his own self-mythologising, perhaps most notably by showing how he was before the mid 1920s far more interested in the New Age world of Theosophy than he was later ready to acknowledge. They also show how the dramatic change in the tone of his writing during the second half of the 1920s was shaped by a deep sense of crisis in his personal life. There is by contrast little material available for the 1930s, although some of the documents hidden in the archives do show the extent of Graham’s connections with the Yugoslavian political elite, which he used extensively when writing his study of the assassination of King Alexander in 1934. Graham never made any secret of his sympathy for the Serbian national cause, which meant that he was during the Second World War a strong supporter of General Mihailović’sChetniks, whose rumoured collaboration with the Nazi occupying forces caused huge controversy in London during the years before 1945. Although Graham never abandoned his Serbian loyalties, they may have been controversial enough to encourage him to say little about Yugoslavia in his memoirs, even though he readily acknowledged in Part of the Wonderful Scene that he spent almost as much time there as he did in Russia. He said still less about the final years of his life, which were mostly spent at his long-time home in Soho, a period when he was dogged by ill health and found it increasingly hard to come to terms with the changing landscape of modern Britain.

Graham has, like so many writers, suffered the indignity of becoming a forgotten person. It was indeed a fate that he suffered when still alive, for in the final decades of his life the market largely disappeared for the kinds of books he wanted to write. The middle-brow fiction he specialised in during the 1930s seemed almost unbearably quaint when he tried to reproduce the formula twenty years later. Word pictures of London appeared positively archaic when the British public could watch the coronation live on television. The ultimate indignity for Graham’s legacy came at the end of the twentieth century, when the Spanish novelist Javier Marias wrote a book Negra espalda del tiempo (Dark Back of Time) which was largely woven around the relationship between Graham and his friends Wilfrid Ewart and John Gawsworth. It was precisely the fact that these characters had all but disappeared from memory, lurking only in the recesses of unread books, that intrigued Marias enough to weave a complex narrative around a trio who had lost their flesh and blood substance and been reduced to names on a page. Graham has on occasion attracted the attention of some other contemporary writers, including the environmentalist Annie Dillard in Pilgrim at Tinker’s Creek, whilst Robert Macfarlane devoted several pages of his wonderful book The Wild Places to an affectionate review of Graham’s descriptions of the joys of walking. In the 1990s, The Times journalist Giles Whittell followed the route of Graham’s 1914 trek through central Asia to the Altai Mountains when writing his book Extreme Continental. Such references are, however, the exception rather than the rule. Graham has not even figured much in the dry pages of academic tomes, cropping up as the subject of a few articles by western and Russian scholars, and appearing in a few anthologies of travel-writing.3 Numerous copies of his books still reside on the dusty shelves of libraries across Europe and North America, but their author has largely faded into obscurity, a name in a card index or an entry in a computerised catalogue linked to the keywords ‘Russia’ and ‘tramping’. All of which raises the question of why Graham should still be of interest today?

The previous few pages have started to provide an answer. Graham had a high profile as a writer for much of his life. His articles in the press were almost invariably published with a note that he was a “famous” or “celebrated” travel writer; he was a familiar enough figure to appear as a caricature in some of the cartoons which appeared in the literary magazines of the inter-war years; and, of course, he was a hugely significant figure in shaping British attitudes towards Russia during the years before the 1917 Revolution. Graham’s complex and at times convoluted philosophy of life is also of interest, since it illustrates neatly how the discontents of modernity can stimulate a search for ideas and ideals that offer a compensating sense of harmony. His descriptions of landscape, and his ruminations on the role of rural life in compensating for the artificiality of the city, speak directly to a contemporary world familiar with the imperatives of a green agenda that seeks to build a new relationship between humanity and the natural world. His ruminations on matters spiritual have a remarkable symmetry with many contemporary New Age preoccupations. Perhaps above all, though, Graham simply had a fascinating and incident-filled life. He was born at a time when William Gladstone was Prime Minister and Queen Victoria had yet to celebrate her golden jubilee. He died when Harold Wilson was in Downing Street and Queen Elizabeth II had been on the throne for more than twenty years. During that time Graham travelled on four continents. He met monarchs and politicians, bishops and authors, prostitutes and vagabonds. He survived a hit on his house in the London Blitz. He enjoyed, in short, both the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. Graham’s prodigious output as a writer is staggering even in an age of word processors and the internet. The life he both chronicled and concealed deserves a new audience.

The writing of a ‘Life’ is, it goes without saying, an intensely personal process. Any biographer who seeks to tell the story of someone they never met will know how their quarry manages to be both deeply familiar and strangely elusive at one and the same time. The challenge they face in recreating their subject is not simply the lack of sources capable of yielding definite insights and perspectives. It is instead the difficulty of entering into a private mental realm of assumptions and values that are by their very nature inchoate and uncertain. Nor is it ever a straightforward business to recreate a world – social, cultural, intellectual – whose contours have changed so greatly over time. In the words of Richard Holmes, that most distinguished practitioner of the biographer’s art, you can pursue your quarry but never hope to catch them, but must instead be content to sketch out the “fleeting figure” who never stands still long enough to be caught.4 This project started out, at least in its early stages, as a kind of modern travelogue designed to return to the places Graham knew in order to reflect on the changes that have taken place since the days he toured the world. It soon became apparent that such a bold plan was doomed to frustration. Graham travelled astonishing distances in an age before the dawn of widespread air travel (his first long-distance flight did not take place until he was in his eighties). To follow in his footsteps – from western Russia to Siberia, from Europe to Africa, from Canada to Mexico – would be the work of years even in an age of motorways and jet aircraft. But, and perhaps more importantly, the world that Graham knew has in many respects changed so greatly that to follow his footsteps in such detail would constitute an exercise in mere cartography. It would give precedence to the idea of ‘place’ as a set of coordinates over ‘place’ as a complex amalgam of history and story refracted through the vision of the people who experience it. Graham was in his travel writing adept at painting vivid portraits of the people he met and the landscapes he passed through. But he was also always searching for a ‘spirit of place’ that lay beneath the surface, a spirit shaped both by the past and by a strong sense that the richness of human experience rested on something more profound and elusive than its material substratum. Much of his early travel writing in particular was less about place as a location in time and rather about place as a meeting of the eternal and the temporal. It was only after he left Russia behind – or rather that Russia left him behind – that his work began to focus more immediately on the things he heard and saw on his long journeys through Europe and North America.

I have been fortunate enough down the years to travel to many of the places Graham visited. Russia is, so to speak, at the heart of my professional oekumene, the place I have written about over many decades, living in and visiting the country many times in both its Soviet and post-Soviet guises. The cities of Europe and North America about which Graham wrote so copiously – Prague, Vienna, Warsaw, Berlin, Chicago, New York – have also countless times been on my itinerary. The south-western states of America similarly feature in the mouldering collection of airline tickets hidden away somewhere in a storage cupboard. Only the Rocky Mountains and the mountains of central Asia have remained for me entirely terra incognita. It would nevertheless by untruthful to claim with much passion that I have been able to find Graham in the places he visited. The worst slums of Chicago’s West Side and the New York Bowery have long since disappeared. Soviet planners swept away much of old Moscow, leaving Red Square and the Kremlin as glorified museums, echoes in brick and stone of a world that has long vanished. The vagaries of time and war have changed places like Berlin, Prague and Constantinople beyond all recognition. Even Graham’s long-time home at 60 Frith Street, in London’s Soho, has been through so many incarnations since his death that its brick facade and black front door seem now to have no memory of his presence. If ghosts are – as some believe – electronic emanations of people long departed, then Graham seems to have had no desire to haunt the world. He lives instead in the numerous books and journals he left behind.

There is one exception to this rule. Not long before the completion of this manuscript, I was lucky enough to visit the Old Believer settlements that stretch along the shore of Lake Peipsi in modern Estonia. The Orthodox Old Believers, religious dissidents who rejected the church reforms introduced by Patriarch Nikon in the seventeenth century, fled central Russia in search of more remote areas where they could live their lives free from persecution. Their descendants who live today on the banks of Lake Peipsi maintain many of the Old Believer traditions, both secular and religious, and to wander through the wooden houses of their villages is to get a sense of the old Russia. Even the presence of cars and electric light – de rigueur in such a determinedly modern country as Estonia – cannot conceal altogether the shards of the past. At one point during the visit I stood on a rock on the shore of the lake, looking out across the water towards Russia, which remained stubbornly invisible in the haze of a fine September day. When Graham was a young man in London, Russia became for him a half-mythical place, a “Somewhere-Out-Beyond”, where he believed that he could find a life more fulfilling than one that involved a daily commute from Essex into London where he worked as a junior civil servant. By the time he visited the Old Believer settlements in 1924, seven years after the Revolution, Russia was closed to him and he could do no more than search for echoes of the country he had loved so dearly. As I peered towards the horizon across Lake Peipsi, trying to catch a glimpse of the Russian shore, it occurred to me that Graham had like all true pilgrims spent his life in search of something that he was doomed never to find. Much of his work was driven by a desire to make actual in the world the ideals he saw in his imagination. The visions that he sought to portray sometimes seemed to him tantalisingly close. At other times they seemed far away. The following chapters will show that Graham was despite his much-vaunted ‘idealism’ – his sense that the world was shaped by forces more profound than could be discerned in the rhythms of ordinary life – surprisingly adept at using his pen to capture the foibles and idiosyncrasies of the people he lived amongst. Aware of two worlds, but at home in neither, Graham’s story was in the deepest sense of the term a religious one.

1 The Times, 20 March 1975.

2 Stephen Graham, With the Russian Pilgrims to Jerusalem (London: Macmillan, 1913), p. 12, available at http://archive.org/details/withrussianpilgr00grahuoft.

3 For recent Russian discussions of Graham see S. Nikolaevna Tret’iakova, ‘Angliskii pisatel’-puteshestvennik Stefan Grekhem o Rossii nachala XX veka’, Voprosy istorii, 11 (2002), pp. 156–60; S.N. Tret’iakova, ‘Rossiia v tvorchestve i sud’be Stefana Grekhema’, in A. B. Davidson (ed.), Rossiia i Britaniia: Sviazi i vzaimnye predstavleniia XIX–XX veka (Moscow, 2006), pp. 220-27; Olga Kaznina, Russkie v Anglii (Moscow: Nasledie, 1997), 104-06. In English see, for example, Michael Hughes, ‘The Visionary Goes West: Stephen Graham’s American Odyssey’, Studies in Travel Literature, 14, 2 (2010), pp. 179-96; Michael Hughes, ‘The Traveller’s Search for Home: Stephen Graham and the Quest for London’, The London Journal, 36, 3 (2011), pp. 211-24. Some of Graham’s writings on New York have appeared in Philip Lopate (ed.), Writing New York (New York: Library of America, 1998), pp. 487-96. A valuable overview of Graham’s publications can be found in Marguerite Helmers, ‘Stephen Graham’, Dictionary of Literary Biography, vol. 195, pp. 137-54.

4 Richard Holmes, Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer (London: Harper Perennial, 2005), p. 2

http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0040.11

1. Chasing the Shadow

Stephen Graham was born in Edinburgh in March 1884, in a house near Calton Hill, distinctive then as now for the Parthenon-like monument that caps its summit, designed by the architect William Playfair as a memorial for those who died in the Napoleonic wars. It was snowing heavily, not a particularly unusual event for the final weeks of winter in Scotland’s capital city, but still rare enough for the young Stephen to be regaled throughout his childhood with stories of how the “big wet snow-flakes” had driven against the windows on the day he entered the world. He was still speculating eight decades later whether his fascination with snow had been one of the factors that first led him to Russia.

Graham’s early life remains surprisingly impervious to even the most sleuth-like biographical inquiry, for despite the confessional style that became the hallmark of so much that he wrote, his apparent candour often concealed a good deal more than it exposed. His description of childhood fills fewer than three pages of the autobiography he published in 1964, and the few episodes he chose to recall have a slightly fantastic character about them, coloured both by the passing of the years and his life-long vivid imagination.1 Stephen remembered himself as a toddler with “golden curly hair”, dressed like a girl, who was stolen away by the gypsies to “begin a begging career”. All came right, though, when he was found by the police and returned home, after which his father cut off his flowing locks and dressed him in an altogether more masculine sailor suit. Graham’s other recollections of childhood were equally episodic if less exotic. He remembered being a chronic sleepwalker, his nocturnal ramblings often concluded by a swift clip round the ear from his father, who was seemingly untroubled by the prospect of startling his son into wakefulness. He also recalled how his best friend Kenny Self helped to foster in him an interest in moths and other insects, that led him to become an avid youthful collector of lepidoptera, earning him the nickname “legs and wings” from his childhood friends.2 “Our friendship lasted six or seven years. During that time I was in love with him, make of that what you will. At night I used to haunt the street where he lived, watching for a glimpse of his face at a window. I hoped that his house would burn down so that I might rush through the flames to save him”. The two boys also acted together in a school production of A Merchant of Venice, Kenny taking the part of the maid Nerissa, and Stephen the role of Portia, who dons men’s clothing in order to masquerade as a lawyer to defend Antonio from Shylock’s bloodthirsty demand for his pound of flesh. It would be unwise to read too much into such memories. It was, after all, inevitable that boys would have to play female parts in an education system that was strictly segregated by sex. Graham’s recollections cannot in any case always be trusted. An unwavering commitment to the accurate delineation of past events was never the hallmark of his literary work. The brief hotch-potch of childhood anecdotes recounted in the opening pages of the published version of Part of the Wonderful Scenewas designed to provide colour rather than insight. It may also have been designed to conceal some of the oddities of his upbringing. The eighty-year old Graham had little real interest in regaling his readers with accurate remembrances of his eight-year old self.

The father who cut off young Stephen’s golden hair was the journalist and future Country Life editor Peter Anderson Graham (invariably known professionally by the moniker P. Anderson Graham). Graham senior had been born in 1856, in the border town of Crookham in Northumbria, the second eldest of a family of four boys and one girl. The Graham clan subsequently moved to Edinburgh, where they settled in Arthur Street, just a few minutes from the city centre. The family circumstances were not particularly prosperous. The 1881 census, which noted Anderson Graham’s profession as “journalist and leader writer”, also recorded that two of his brothers were respectively a “press-maker” and a “journeyman ironmonger”. The third was an apprentice draper. Their father worked as a “weigher” at one of Edinburgh’s numerous train stations (although his profession was recorded in a later census as railway clerk). Despite this less than propitious background for a literary career, Anderson Graham was able to attend Edinburgh University, before subsequently establishing himself on the Edinburgh Courant, a Conservative paper whose contributors were committed to countering the Liberal influence of The Scotsman in “this Whig-ridden country”.3 Stephen Graham subsequently recalled that his father was always a “hot Tory”.

Anderson Graham later belonged to the circle of young men who surrounded the celebrated writer and critic W.E. Henley, famous amongst other things for his assault on the aestheticism of Aubrey Beardsley and Oscar Wilde, as well as his memorable dismissal of socialism as the “dominion of the common fool”.4 Henley had first travelled to Edinburgh in 1873 to seek medical treatment from Joseph Lister, the pioneer of antiseptic surgery, during which time he became a close friend of the novelist and travel-writer Robert Louis Stevenson. He returned to Scotland at the end of the 1880s, as editor of the newly-established Scots Observer, before going back to London in 1892 to edit the paper under its new and more imposing title of the National Observer. It was during this period that he became celebrated for furthering the careers of a whole host of young writers including J.M. Barrie and Kenneth Grahame. It was also during this time that Anderson Graham came firmly into Henley’s orbit, although the two men may have met earlier during the latter’s previous sojourns in Edinburgh. Anderson had moved his family from Edinburgh to Gloucestershire soon after Stephen was born, to take up the editorship of the Gloucestershire Echo, a provincial paper of some importance, but within a short time he decided to give up his post in order to move to London and concentrate on his literary ambitions. Stephen later recalled that during this time, when the family lived in Hornsey, they were “very poor”, with the result that he was expected to act as “shopper for the family, saving a penny there and a ha’penny here”.5 His memory of events may once again have been over-coloured; although the family’s pecuniary circumstances imposed on them a frugal life-style, not least because there were by the mid 1890s six children to feed and clothe, there was still enough money to keep a maid. The area of London they lived in was in any case characterised more by genteel poverty than real material deprivation. The family’s life-style would have been familiar to the fictional Mr Pooter, the pompously respectable clerk whose ruminations on life feature in George and Weedon Grossmith’s comic classic Diary of a Nobody, first published in Punch at the end of the 1880s, when the Grahams were already resident in Hornsey.

Stephen’s family was, then, a literary if impecunious one. His mother Jane (née Macleod) had been a librarian before her marriage to Anderson Graham in Edinburgh in 1881. Her son later spoke of how she “handled first editions of Ruskin and Browning” – two of his favourite childhood authors – although a moment’s reflection suggests that, since both men were still alive when Jane was working, this was more a statement of fact than any indication that she once enjoyed privileged access to rare material.6 Graham also recalled how his mother seemed to him as he grew up like a character in a Walter Scott novel – “unhappy, pure, romantic and heroic”.7 Jane certainly had a deep aversion to the mundane business of household management, preferring to bury her head in a book, which perhaps explains why Stephen was promoted at a young age to the status of the family’s shopper-in-chief. It is also clear that she represented a potent presence in her son’s life, even though he barely mentioned her in his autobiography. During a deep personal crisis in his mid-forties, soon after she died, he wrote private notes of anguish to her in the diary he kept detailing the depths of his despair.

The best portrait of Jane appears in Graham’s 1934 novel Lost Battle which detailed, in a thinly-fictionalised form, the disintegration of his parents’ marriage, as it collapsed around 1900 when Anderson Graham left home to establish a new life elsewhere. A shy and retiring woman, who had few relationships outside the home, Jane had a strong taste for “literary romanticism” and spent much of her time reading the novels of Scott. She also read a great deal of French and Italian literature. “Jeannie Macrimmon” – as she appears in Lost Battle – developed a close and even intense relationship with her eldest child Mark (the alter ego of Stephen Graham himself). The two often stayed up late whilst the mother read to her son, dreaming that he might one day become a celebrated writer, succeeding in the literary world that tantalized her so greatly but which always appeared so remote. Although “Jeannie” was devoted to her other five children – four girls and a boy – it was in Mark that she seemed to find a sympathetic spark for her “romantic and imaginative” nature. The relationship provided her with some kind of emotional compensation for what was, at least to the jaundiced eyes of Stephen Graham as he looked back from the vantage point of later years, his parents’ joyless and empty marriage.

The portrait of Anderson Graham painted by his son in Lost Battle was far more acerbic. The character of John Rae Belfort – as Anderson appears in the book – could hardly have been more different from that of his wife. Whilst “Jeanie Macrimmon” was mild-mannered and other-worldly, “John Belfort” was a hard-drinking and irascible individual, who desperately aspired to a literary career, but was constantly frustrated at having to turn his hand to hack-work to support his large family. He also possessed a fierce temper that inspired considerable trepidation in his wife and children. When at home in Essex – where the real Graham family moved in the early 1890s – John Belfort spent most of his time alone in his study playing chess. He could also be heard from time to time pacing up and down his bedroom reciting old Scottish ballads for hours on end.

The fictional Belfort achieved some success by writing about agricultural issues – as did Anderson Graham – and his absence from home on periodic tours around Britain was welcomed by his wife and children who relished the peace that reigned when he was away. The brittle marriage that Stephen Graham portrayed in Lost Battle finally came to an end when Belfort left home for a much younger woman. The book traces how the grown-up Mark, by now a successful writer in his own right, gradually re-established a relationship with his father and his two children by his second “marriage” (Belfort, like Anderson, never formally divorced his first wife). It is difficult to know to what extent Lost Battle represented anything more than a thinly-fictionalised account of the Graham household. The census records show that by 1911 Anderson Graham was living apart from his family with two new children in St Albans, although he had left his first family many years earlier, probably when Stephen was about sixteen. In the years that followed he built a substantial house in large grounds near Hemel Hempstead in Hertfordshire, paid for by his earnings from Country Life, and a series of articles on rural affairs in publications including the Morning Post and the St James’ Gazette. The portrait of John Rae Belfort in Lost Battle certainly tallies with the little that is known of the biography and character of Anderson Graham himself. Stephen remarked in his diary after his father’s death that there were many mysteries about his family that he could never fathom. The same uncertainties confront his biographer.

Anderson Graham was, like many of those who made up the world of late Victorian belles lettres, very much a professional writer, dependent on his pen to earn his living, rather than a gentleman of leisure blessed with the means to contribute to the press according to his particular whim and interest. His articles appeared in publications ranging from the Evening Standard and the Morning Post to Longman’s Magazine and The New Review. Stephen later remembered that it was his father who “taught me to write”, making him re-tell the story of Kidnapped in sentences of no more than sixteen words, an exercise designed to emphasise the importance of brevity in effective communication. Despite the acerbic portrait of Anderson Graham in Lost Battle he still seems to have had a significant influence on his son’s early life, not least in helping him realise that a literary career would always involve as much grind as inspiration. Stephen’s later work-ethic and pride in earning his living from his pen were doubtless inherited from his father – just as the more intuitive and instinctive side of his character seems to have been shaped by his mother.

Graham père also in later years provided his eldest son with valuable advice about publishing his work, and opened the columns of Country Life to him at a time when Stephen was still struggling to find a market for his writing (the two men seem to have re-established their relationship after the hiatus caused by Anderson’s departure from the family home in Essex). Stephen later returned the favour by helping his father to publicise his now long-forgotten science fiction novel, The Collapse of Homo Sapiens (1923), which Anderson published when he was in his mid-sixties, long after any fame he once enjoyed had been eclipsed by his son’s. Nor was Stephen the only child in the Graham household to inherit the literary gene. His younger sister Eleanor was in later life to achieve fame as a children’s author, most notably with The Children who Lived in a Barn, as well as playing a key role in establishing the celebrated Puffin series of books, which published such classics as Barbara Euphan Todd’s Wurzel Gummidge and Roger Lancelyn Green’s version of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table.

Anderson Graham’s influence on his son was not confined to advising him about the skills he would need to succeed as a professional writer. He also propagated in him a suspicion of the modern world that was to become a defining motif in the books that Stephen later wrote about his time in pre-Revolutionary Russia. Anderson Graham was from a young age concerned about the declining health of rural Britain, fearing that the rhythms of traditional society were being undermined by the twin processes of industrialisation and urbanisation, a theme that ran through his 1892 book The Rural Exodus. Although he told his readers that addressing the problem should not become a matter of party politics, there was something profoundly Tory about his prescriptions, which were rooted in a sense that any changes should take place “slowly and gradually” and be rooted “in the hearts and minds of the people”.8 Nor was Anderson Graham’s concern about the countryside simply a matter of economics and sociology. He also had a strong interest in the natural world (although this may in part have been prompted by his recognition that there was a ready market for books and articles on the subject). His first lengthy published work on Nature in Books, which appeared in 1891, contained essays on the naturalist Richard Jefferies and the American transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau. His third book, All the Year with Nature (1893), which was dedicated to W.E. Henley, contained a series of articles on topics ranging from ‘Birds-Nesting’ through to ‘The Harvest Labour’. Although most of the pieces were quite light-hearted, if sometimes marred by a rather laboured whimsy, their author did occasionally intersperse his meditations with more serious reflections on the state of rural society. He also succumbed to a lyrical celebration of the English countryside, despite half-jestingly warning against such extravagance, writing movingly of his love of winter evenings when “the distant woods are visible in the last streaks of daylight, and the blackening train of crows are hurrying to cold perches on the oaks”.9

The essays in Nature in Books were more serious in tone, suggesting that whilst all human beings would in time become weary of seeking fame or material possessions, the appeal of “the music and pageantry of earth” would never fail.10 Although Anderson Graham did not share the nature-mysticism of Richard Jefferies, he provided a sensitive account of his work, showing how Jefferies’ love of the countryside provided him with a sense of meaning missing elsewhere in his life. And, in his chapter on Wordsworth, Anderson firmly dismissed critics who failed to engage with the poet’s religious views or rejected them as incoherent and immature. He criticised those who refused to see in nature anything more than an impersonally bleak world, arguing that “Right as it is for us to know and feel something of the sadness and melancholy that cast their sober mantle over so much of the universe, it is no less desirable to avoid a too morbid gloating over them, and to feel and appreciate the joy that, in spite of artificial restraints, is awakened by the happy carol of a bird, the glow of sunshine, the gambol of younglings, the beauty of landscape”.11 Whilst Graham senior was reluctant to ascribe any definite metaphysical meaning to the natural world, he consciously rejected the post-Darwinian sense that the beauty of the countryside represented nothing more than the accidental by-product of natural selection. It was a view echoed many years later by his son, who found in his massive hikes through the Russian countryside a sense of mystery that hinted at realms of meaning lying far beyond the limited horizons of the material world.

The extent to which Anderson Graham was a real countryman is open to debate. Although he was born in rural Northumberland, his parents’ move to Edinburgh took place when he was a young boy, and much of his life was spent in towns and cities. Whilst he discussed the rural economy quite knowledgeably in The Rural Exodus, there is little evidence that he had much real sense of the intricate practices of agriculture. Even though his observations of the natural world were often acute, they showed no real evidence of a deep knowledge of birds and animals. Anderson Graham was certainly a lover of dogs, and his family at various times owned a fox-terrier and a deer-hound called Fingal, presumably named for the character in Ossian, but though he wrote of shooting and hunting it is not clear that he was a passionate devotee of country sports.12 Nor is it clear to what extent Stephen Graham’s own early years were actively shaped by his father’s uncertain interest in rural affairs. Anderson published a book called Country Pastimes for Boys,13 when Stephen was thirteen, which contained various Boy’s Own information on such topics as collecting birds’ eggs and catching fish. The book was, however, written for an essentially suburban middle class readership, anxious to find ways of ensuring that their children had something to do in the holidays, rather than an audience who already possessed an intimate knowledge of the countryside. Stephen’s own interest in lepidoptery comes across as that of a child raised in the suburbs, rather than characteristic of a boy intimately familiar with the life of the fields, although a fictionalised account of his early childhood published in the early 1920s revealed the depth of his passion for the subject.14 Anderson Graham may well have made a real attempt to inculcate a love of the English countryside in his children, but if he did it would necessarily have been the love of an outsider, given that the family’s daily life was spent in north London and suburban Essex.

P. Anderson Graham’s combination of skills and interests meant that he was a natural choice in 1900 for the post of editor of Country Life, established three years earlier, to capitalise on a wistful nostalgia for an imaginary rural past amongst a middle class readership that overwhelmingly derived its income from commerce and industry.15 The Arts and Crafts movement had been in full swing in Britain from the 1880s, characterised by a search for a new aesthetic style in art and architecture, intended to counter the soulless products of a mechanised age which denigrated the craft principle in favour of industrial efficiency.16 In a supreme irony, the search for the authentic and traditional quickly became big business, as magazines like Country Life promoted such products as wood panelling from Liberty’s of London, designed to adorn the dining rooms of the expensive new country homes advertised in its property pages. The magazine also carried numerous articles about aspects of rural life, ranging from stock-breeding through to fox-hunting, as well as publishing more literary pieces about travel and politics.

Anderson Graham was well-suited to manage such an enterprise (he also contributed many of the magazine’s articles and columns). He had for many years been a devotee of John Ruskin, who served as a kind of guru for the Arts and Crafts movement, whilst his own idealised view of the English countryside dovetailed neatly with the ethos that Country Life tried so hard to promote. Anderson also possessed the hard journalistic skills needed to ensure that the magazine was run professionally, and responded to the demands of its readership, who bought it precisely because they aspired to the life-style it promoted. The portrayal of the English countryside that appeared in Country Life under Anderson Graham’s editorship was a commercial product, reflecting the financial imperatives of a journalism that pandered to the longings of a particular section of urban society. The Russia that Stephen Graham was later to place before his readers was also in large part a fictional product, reflecting the hopes and dreams of its author, whilst at the same time being carefully calculated to appeal to the instincts and yearnings of his audience. He was, like his father, adept at recognising that romantic nostalgia and distrust of the modern industrial world were marketable commodities, capable of appealing to an urban readership anxious to hear about worlds they could imagine but never inhabit.

The young Stephen Graham was educated at Sir George Monoux Grammar School in Chingford, where he proved an able if sometimes lazy student, who had to be bribed by his father to apply himself properly to his studies. He made his greatest mark on the Latin teacher, one Mr Adams, who took a shine to his young pupil and awarded him the highest grades of any boy in class, before abandoning his teaching career to take up farming. Graham was in his own words, “always fighting, playing practical jokes, committing juvenile crimes, and getting chased by the police”, memories that he drew on many years later in his 1922 novel Under-London, which described the lives of a small group of boys growing up in an East London suburb at the end of the nineteenth century. Despite his various misdemeanours, Graham became School captain, a result he believed of his popularity with the other boys as well as many of the masters.17 He left at fifteen because his father was too poor to send him to university – the lucrative Country Life appointment still lay a year ahead – and within a few months Stephen was commuting to work as a clerk in the Bankruptcy Court at Carey Street in central London.

Anderson Graham was instrumental in encouraging his son to join the Civil Service, pointing out the benefits of a regular income and pension denied to the freelance journalist. Graham’s office duties were very dull, consisting of routine clerical work and the daily distribution of the mail, but he at least had time to pursue his interest in literature. Within a few years he progressed to a post as staff clerk at Somerset House, where the grind of office life was interspersed with games of table-tennis in the basement, along with debates amongst “a distinguished company of young men” about such topics as “the Basis of Love”.

Graham fell in love with a series of young women during these years, although his idea of courtship seems to have been excruciatingly earnest, consisting largely of forays into the countryside to engage in discussion about the virtues of various poets. There was a good deal of interest in literary matters amongst the clerks at Somerset House, several of whom later progressed to careers in journalism, and they eagerly followed such contemporary controversies as the dispute between Hilaire Belloc and George Bernard Shaw that followed the publication of the former’s The Servile State.18 Graham himself read widely – Ruskin and Carlyle being particular favourites – but the course of his life changed one day when he found a battered copy of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment on sale in a barrow in central London. He was immediately captivated by the brooding story of the student Raskolnikov, whose life was haunted by remorse following his murder of an elderly female pawnbroker, undertaken in a desperate act of defiance to assert his autonomy from the moral claims of the world around him. The “grand discovery” of an author who had, in Graham’s words, “passed into oblivion”, prompted the start of his life-long love affair with all things Russian. He insisted on sharing his discovery with a girlfriend who was ten years his senior, another harbinger of his future life, for Graham was over the next few years repeatedly attracted to women considerably older than himself.

Graham was right in suggesting that Dostoevsky commanded little interest in Britain in the early 1900s. Although a number of his novels had been translated into French and English some years earlier – and subsequently became very popular during the First World War – the author of Crime and Punishment was not particularly widely read in Britain during the early years of the twentieth century.19 Russia itself had for centuries been seen by many Britons as little more than a remote and sinister void on the periphery of Europe. The era of the Great Game – that curious nineteenth-century duel of British and Russian soldier-explorers played out in the remote deserts and mountains of central Asia – helped to fuel the idea that Tsarist Russia was a natural enemy of the British Empire.20 Nor was Anglo-Russian antagonism simply a matter of geopolitics. The final decades of the nineteenth century also witnessed a growing campaign by British radicals to warn their fellow-countrymen that the despotic Russian Government posed a major challenge to the liberties and security of the entire continent.21 H.G. Wells, who in the years before the First World War shared this bien-pensant distaste for the empire of the tsars, later summarised the situation accurately when he recalled that for many Britons, Russia had always seemed “a fabulous country […] a wilderness of wolves, knouts, serfdom, and cruelty [as well as] Bogey Russia, which had ‘designs’ – on India, on all the world”.22