8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

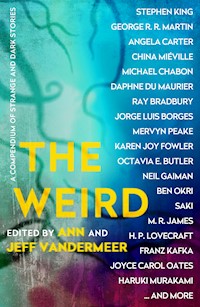

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

From the Author of Annihilation, now a major Film adaptation starring Natalie Portman. Shortlisted for the World Fantasy Award, the Nebula Award and the Locus Award. AMBERGRIS: 239 Manzikert Avenue, Apartment 525. Two dead bodies lie on a dusty floor. One corpse is cut in half, the other is utterly unmarked. Only one is human. Ambergris is occupied, ruined and rotting. Its buildings are crumbling, or mutating into moist and hostile new life forms. The population is brought to its knees by narcotics, detention camps and arbitrary acts of terror. And for motives unknown, the new masters of the city want this bizarre case closed. Now. With no leads and one week to conclude his investigation, Detective John Finch is about to find himself in the cross-hairs of every spy, rebel, informer and traitor in town. And what he discovers will change Ambergris forever...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

JEFF VANDERMEER is the winner of two World Fantasy Awards and has been shortlisted for the Hugo Award, the Bram Stoker Award and the Philip K. Dick Award. Finch was nominated for the World Fantasy Award, the Nebula Award and the Locus Award.

First published in the United States of America in 2009 by Underland Press.

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2011 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Jeff VanderMeer, 2009

The moral right of Jeff VanderMeer to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents act of 1988.

All quotes in Finch from Shriek: An Afterword are copyright © Tor Books, 2006 and are used by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. All characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 1 84887 478 7 eISBN: 978 0 85789 357 4

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26-27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

FOR ANN & FOR THE REBEL ANGELS:

Victoria Blake

John Coulthart

John Klima

Tessa Kum

Dave Larsen

Michael Moorcock

Michael Phillips

Cat Rambo

Matt Staggs

“When they give you things ask yourself why.

When you’re grateful to them for giving you the things you should have anyway, ask yourself why.”

—Lady in Blue, rebel broadcast

CONTENTS

MONDAY

1

2

3

4

5

6

TUESDAY

1

2

3

4

5

WEDNESDAY

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

THURSDAY

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

FRIDAY

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

SATURDAY

1

2

3

4

5

SUNDAY

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE BOOK

MONDAY

Interrogator: What did you see then?

Finch: Nothing. I couldn’t see anything.

I: Wrong answer.

[howls and screams and sobbing]

I: Had you ever met the Lady in Blue before?

F: No, but I’d heard her before.

I: Heard her where?

F: On the fucking radio station, that’s where.

[garbled comment, not picked up]

F: It’s her voice. Coming up from the underground. People say.

I: So what did you see, Finch?

F: Just the stars. Stars. It was night.

I: I can ask you this same question for hours, Finch.

F: You wanted me to say I saw her. I said I saw her! I said it, damn you.

I: There is no Lady in Blue. She’s just a propaganda myth from the rebels.

F: I saw her. On the hill. Under the stars.

I: What did this apparition say to you, Finch? What did this vision say?

1

Finch, at the apartment door, breathing heavy from five flights of stairs, taken fast. The message that’d brought him from the station was already dying in his hand. Red smear on a limp circle of green fungal paper that had minutes before squirmed clammy. Now he had only the door to pass through, marked with the gray caps’ symbol.

239 Manzikert Avenue, apartment 525.

An act of will, crossing that divide. Always. Reached for his gun, then changed his mind. Some days were worse than others.

A sudden flash of his partner Wyte, telling him he was compromised, him replying, “I don’t have an opinion on that.” Written on a wall at a crime scene: Everyone’s a collaborator. Everyone’s a rebel. The truth in the weight of each.

The doorknob cold but grainy. The left side rough with light green fungus.

Sweating under his jacket, through his shirt. Boots heavy on his feet.

Always a point of no return, and yet he kept returning.

I am not a detective. I am not a detective.

Inside, a tall, pale man dressed in black stood halfway down the hall, staring into a doorway. Beyond him, a dark room. A worn bed. White sheets dull in the shadow. Didn’t look like anyone had slept there in months. Dusty floor. Even before he’d started seeing Sintra, his place hadn’t looked this bad.

The Partial turned and saw Finch. “Nothing in that room, Finch. It’s all in here.” He pointed into the doorway. Light shone out, caught the dark glitter of the Partial’s skin where tiny fruiting bodies had taken hold. Uncanny left eye in a gaunt face. Always twitching. Moving at odd angles. Pupil a glimmer of blue light at the bottom of a dark well. Fungal.

“Who are you?” Finch asked.

The Partial frowned. “I’m—”

Finch brushed by the man without listening, got pleasure out of the push of his shoulder into the Partial’s chest. The Partial, smelling like sweet rotting meat, walked in behind him.

Everything was golden, calm, unknowable.

Then Finch’s eyes adjusted to the light from the large window and he saw: living room, kitchen. A sofa. Two wooden chairs. A small table, an empty vase with a rose design. Two bodies lying on the pull rug next to the sofa. One man, one gray cap without legs.

Finch’s boss Heretic stood framed by the window. Wearing his familiar gray robes and gray hat. Finch had never learned the creature’s real name. The series of clicks and whistles sounded like “heclereticalic” so Finch called him “Heretic.” Highly unusual to see Heretic during the day.

“Finch,” Heretic said. “Where’s Wyte?” The wetness of its moist glottal attempt at speech made most humans uncomfortable. Finch tried hard to pretend the ends of all the words were there. A skill hard learned.

“Wyte couldn’t come. He’s busy.”

Heretic stared at Finch. A question in his eyes. Finch looked to the side. Away from the liquid green pupils and yellow where there should be white. Wyte had been sick off and on for a long time. Finch knew from what, but didn’t want to. Didn’t want to get into it with Heretic.

“What’s the situation?” Finch asked.

Heretic smiled: rows and rows of needle lines set into a face a little like a squished-in shark’s snout. Finch couldn’t tell if the lines were gills or teeth, but they seemed to flutter and breathe a little. Wyte said he’d seen tiny creatures in there, once. Each time, a new nightmare. Another encounter to haunt Finch’s sleep.

“Two dead bodies,” Heretic said.

“Two bodies?”

“One and a half, technically,” the Partial said, from behind Finch.

Heretic laughed. A sound like dogs being strangled.

“Did the victims live in the apartment?” Finch asked, knowing the answer already.

“No,” the Partial said. “They didn’t.”

Finch turned briefly toward the Partial, then back to Heretic.

Heretic stared at the Partial and he shut up, began to creep around the living room taking pictures with his eye.

“No one lived here,” Heretic said. “According to our records no one has lived here for over a year.”

“Interesting,” Finch said. Didn’t interest him. Nothing interested him. It bothered him. Especially that the Partial felt comfortable enough to answer a question meant for Heretic.

The curtains had faded from the sun. Tears in the sofa like knife wounds. The vase looked like someone had started a small fire inside it. Stage props for two deaths.

Was it significant that the window was open? For some reason he didn’t want to ask if one of them had opened it. Fresh air, with just a hint of the salt smell from the bay.

“Who reported this?” Finch asked.

“An energy surge came from this location,” Heretic said. “We felt it. Then spore cameras confirmed it.”

Energy surge? What kind of energy?

Finch tried to imagine the rows and rows of living receivers underground, miles of them if rumor held true. Trying to process trillions of images from all over the city. How could they possibly keep up? The hope of every citizen.

“Do you know the . . . source?” Finch asked. Didn’t know if he understood what Heretic was telling him.

“There is no trace of it now. The apartment is cold. There are just these bodies.”

“How does that help me?” he wanted to say.

Finch usually dealt with theft, domestic abuse, illegal gatherings. Flirted with investigating rebel activity, but turned that over to the Partials if necessary. Tried to make sure it wasn’t necessary. For everyone’s sake.

Murder only if it was the usual. Crimes of passion. Revenge. This didn’t look like either. If it was murder.

“Anyone live in the apartments next door?”

“Not any more,” the Partial replied. “They all left, oddly enough, soon after these two . . . arrived.”

“Which means they made a sound.” Or sounds.

“I’ll interrogate anyone left in the building after we finish here,” the Partial said.

What a pleasure that’ll be for them.

Still, Finch didn’t volunteer to do it. Not yet. Maybe after. Not much worse than door-to-door interviews in unfriendly places. Many didn’t believe his job should exist.

“What do you think, Finch?” Heretic asked. Just a hint of mischief in that voice. Laced with it. Just enough to catch the nuance.

I think I just walked in the door a few minutes ago.

The bodies lay next to each other, beside the sofa.

Finch frowned. “I’ve never seen anything quite like it.”

The man lay on his side, left hand stretched out toward the gray cap’s hand. The gray cap lay facedown, arms flopped out at right angles.

“Might be a foreigner. From the clothes.”

The man could’ve been forty-five or fifty, with dark brown hair, dark eyebrows, and a beard that appeared to be made from tendrils of fungus. That wasn’t unusual. But his clothes were. He wore a blue shirt long out of fashion. Strange, tight-fitting long pants. Dirty black boots.

“He’s not from the city,” Heretic said. Again, an inflection that bothered Finch. A statement or a question?

What’s on his mind?

Finch squatted beside the bodies. Took out his useless pen and his useless pad of paper. Above him, the Partial leaned over to take a picture.

The dead gray cap looked like every other gray cap. Except for the one glaring lack.

“I don’t know what caused the injury to the other one, sir.”

I don’t know what caused the leg situation.

“When we find out,” Heretic said, “we will be just as understated.”

The exposed cross section, cut almost precisely at the waist, fascinated Finch. He almost forgot himself, poked at the tissue with his pen.

The cut had been so clean, so precise, that there was no tearing. No hemorrhaging. Finch could see layers. Gray. Yellow. Green. A core of dark red. (A question he was too cautious to ask: Was it always that dark, or only in death?) Within the core, Finch saw a hint of organs.

“Is this . . . normal?” Finch asked Heretic.

“Normal?”

“The lack of blood, I mean, sir,” Finch said.

Gray caps bled. Finch knew that. Not like a stream or a gout, even when you cut them deep, but a steady drip from a leaky faucet. Puncture wounds healed almost immediately. It took a long time and a lot of patience to kill a gray cap.

“No, it’s not normal.” The humid weight of Heretic was at his side now. A smell like garbage and burnt glass. Made him nauseous.

“None of this is normal,” the Partial ventured. Ignored.

Finch looked up at Heretic. From that angle: the pale wattled skin of Heretic’s long throat.

“Do you know who . . .” Finch hesitated. Gray caps didn’t like being called “gray caps,” but Finch couldn’t pronounce the word they did use. Farseneeni or fanaarcensitii? The Partial circled them, blinking pictures through his fungal eye.

“Do you know who that is?” Finch said finally, pointing at the dead gray cap.

Heretic made a sound like something popping. “No. Not familiar to us. We cannot see him,” and Finch understood he meant something other than just looking out a window.

“Have you . . . ?” Couldn’t say the whole sentence. Too ridiculous. Terrifying. At the same time. Have you eaten some of his flesh and picked clean the memories?

But Heretic had been around humans long enough to know what he meant. “We tried it. Nothing that made sense.”

For a second, Finch relaxed. Forgot Heretic could send him, Sintra, anybody he knew, to the work camps.

“If you couldn’t decipher it, how will I?”

Then went stiff. Richard Dorn, a good detective, had questioned Heretic too closely. Nine months to die.

A bullet to the head. In that case.

But the gray cap said only, “With your fresh eyes, maybe you will have better luck.”

Heretic pulled a pouch out of his robes, opened it. Finch rose, stood to the side as Heretic sprinkled a fine green powder over both bodies. Could’ve done it using his own supply, but Heretic enjoyed doing it. For some reason.

“You know what to do,” Heretic said.

In time, a memory bulb would emerge from both corpses’ heads. Did the fanaarcensitii rely too much on what made them comfortable? No autopsies, just mushrooms. But also hardly any experts left to perform them.

Nausea crept back into Finch’s throat. “But I’ve never. Not a gray cap. I mean, not one of your people.”

“We don’t bite.” The grin on that impossible face grew wide and wider. The laughter again, worse.

Finch laughed back, weakly.

“Write down whatever you encounter, whether you understand it or not.”

Mercifully, Heretic looked away. “A gray cap and a man. Dead in such a manner. We need to know everything.”

“Yessir,” Finch said. He couldn’t keep the grimace off his face.

Heretic seemed to take it for a smile. As he walked past on his way to the door, he patted Finch’s elbow. Finch shivered. A touch like wet, dead leaves sewn together and stuffed with meat.

“Report in the morning,” Heretic said. “Report and report and report, Finch.” The laughter again.

Then Heretic was gone. The hallway shadows ate him up, the apartment door opening and closing.

Finch could hear his own breathing. Shallow. The sudden panicked drumming of his heart. The butterfly blinks of the Partial, still snapping photographs.

Took a breath. A second. Closed his eyes.

A sunny day by the river. A picnic lunch. A tree with shade. Long, cool grass. With Sintra.

2

No obvious bullet or stab wounds. No tattoos or other marks. Grunting with the effort, Finch turned the man over for a second. He seemed heavier than he should be. Skin warm, the flesh solid. From the position of the arms, Finch thought they might be broken. A discoloration at the edge of the man’s mouth. Dried blood? When Finch was done, the man settled back into position as if he’d been there a hundred years.

No point checking the gray cap. Their skin didn’t retain marks or burns or stab wounds. Anything like that sealed over. Besides, the cause of the gray cap’s death was obvious. Wasn’t it? Still, he didn’t want to assume murder. Yet.

Out of the four “murders” in his sector over the past year, two had been suicides and one had been natural causes. The fourth solved in a day.

Disappearances were another subject altogether.

He stood. Looked down at the tableau formed by the dead. Something about it. Almost posed. Almost staged. But also: the man’s neck, half-hidden by the shirt collar. Was it . . . twisted? Who could tell with the gray cap. Impossibly long, smooth, gray neck. (Did that mean Heretic was old, this one young?) But also torqued.

Finch glanced up at the tired, sagging ceiling. About ten feet.

“They look like,” Finch said. “They look like they both fell.”

Could that be the sound the neighbors heard?

“The spore camera’s first shot is of them on the floor,” the Partial said.

Finch had forgotten him.

Turned, stared at the Partial. The Partial stared back. Taking Finch’s photo with each blink.

“I could . . .”

“What?” the Partial said. “You could what?”

I could tear out your eye with my bare hands. Not a thought he’d seen coming.

“You know what I think?” the Partial said.

Finch tamped down on his irritation. Tried to remember that, in a way, none of the Partials were more than six years old. Disaffected youths no matter what their age. All pale. Or made pale. Humans who’d gotten fungal infections and liked it, Truff help them. Got an adrenaline rush from heightened powers of sight. Enhanced by fungal drugs autogenerated inside the eye. Pumped into the brain. In a sense, their eye was always looking back at them.

I’ll never know what you think. Not in a million years.

“You volunteered for that,” Finch said. Pointed at the Partial’s eye. “That makes you crazy. So I don’t need to know what you think.”

The Partial snickered. “I’ve heard it all before. And you’ll never know what you’re missing . . . But here’s what I think, whether you want it or not. That man’s not really human. Not really. I should know, right? And something went wrong. And maybe they didn’t die here but were, I don’t know, moved.”

Finch gave the Partial a long glance. Turned to kneel again by the man’s body. The second half of what the Partial had said made less sense than the first.

“Just do your job.” I’ll do mine.

The Partial fell silent. Hurt? Seduced by something new to click?

Finch really didn’t care. Something had caught his attention. Two fingers of the man’s left hand. Curled tight into the palm. Grit or sand under the fingernails. Finch got to his knees, leaned forward, took the man’s hand in his. The warmth of it surprised him, the green spores already ghosting into the flesh. He pried the fingers back. Revealed a ragged piece of paper. A pulse-pounding moment of excitement.

Then he pulled it out. Released the fingers. Let the arm fall. Shielding the paper from the Partial with his body.

Normal paper, not fungal. Old and stained. Torn from a book? He unfolded it. Two words, written hurriedly, in black ink: Never Lost. And below that some gibberish that looked something like bellum omnium contra omnes. Self-contained, or once part of a longer message?

Definitely torn from a book. On the back a printed sentence fragment, “the future can hold when the past holds ambiguity such as this,” and a symbol. Somehow familiar to Finch. Although he didn’t know from where.

Stuck the paper in his boot before the Partial could blink that he’d found something. Got up. Pulled gloves from his jacket pocket and put them on. Opened the pouch at his belt.

Heretic had forgotten the preservatives, but would blame Finch if it wasn’t done. Corpses didn’t last long otherwise. Within fortyeight hours, you’d be breathing them, as the spores did their work.

Carefully, he sprinkled a blue powder across both corpses. Not spores this time, but tiny fruiting bodies. The powder smelled like smoke from the camps to the south. Or the camps smelled like the powder. Pointless to wear the gloves after the hundreds of fungal toxins and experiments that had been released into the air. The millions of floating spore-eyes. Yet still he did it.

Blue mingled with green. The green disappeared as he watched, colonized by the blue. The two bodies would not decay now. They would linger, suspended, until Finch returned to collect their memories.

“. . . and know you don’t want to eat the memories,” the Partial said to Finch’s back. Sounding triumphant.

Finch’s thoughts had been so far away he’d missed the first part.

“Is that all?” Wanted to laugh.

Did they talk this way together in the barracks near the camps where the gray caps housed them like weapons? Spewing out each day and night like black ants. Foraging on the flesh of the city. Observers and security both.

“You’re afraid of change,” the Partial said. “Of being changed. That’s why you hate me.”

Swiveled abruptly in his crouch, hand on his gun. Met the Partial’s corrupted gaze.

“Is that all?” Finch repeated. “I mean, are you done with your picturetaking?”

No skill when every blink was an image. No honor in a perpetual voyeurism. A kind of treason against your own kind. “It warps the privacy of your own life,” Wyte had said once, as if he knew. “Permanent occupation. I wouldn’t want to live that way.” Yet now Wyte did. And so did Finch. In a sense.

“I’m never done,” the Partial said. “And if you’ve got a past, you should be worried. They’ll work through all the records some day. Maybe they’ll find you.”

Funny thing is, Partial, Heretic already knows my past. Most of it. And he doesn’t give a fuck. That’s not who I’m worried about.

Wanted to say it but didn’t. Unsnapped the clasp on his holster. The fungal gun trembled there like a live thing. Wet. Dripping. Useless against a gray cap. Very useful against a Partial. Still human, no matter how much you pretend.

“Get the fuck out of here.”

“I see everything,” the Partial said. “Everything.”

“Yes,” Finch said, “but that’s unavoidable, isn’t it?”

The Partial stared at Finch. Seemed about to say something. Bit down on it, hard. Walked out into the hall. Slammed the door behind him.

Leaving Finch alone with the bodies.

* * *

Now Finch can see the frailty death has lent them. Now Finch can see the vulnerability. The way the light uses them in the same way it uses him. He walks to the window. Looks out across the damaged face of Ambergris.

Six years and I can’t recognize a goddamn thing from before.

Harsh blue sprawl of the bay, bled from the River Moth. Carved from nothing. The first thing the gray caps did when they Rose, flooding Ambergris and killing thousands. Now the city, riddled through with canals, is like a body that was once drowned. Parts bleached, parts bloated. Metal and stone for flesh. Places that stick out and places that barely touch the surface.

In the foreground of the bay stands the scaffolding for the two tall towers still being built by the gray caps. A rough pontoon bridge reaches out to them, an artificial island surrounding the base. The scaffolding rises twenty feet above the highest tower. Hard to know if they are almost complete or will take a hundred years more. Great masses of green fungus cling to the tops. It makes the towers look shaggy, almost as if they had fur, were flesh and blood. A smell like oil and sawdust and frying meat. At dusk each day the gray caps lead a work force from the camps south of the city. All night, the sounds of hammering and construction. Emerald lights moving like slow stars. Screams of injury or punishment. To what purpose? No one knows. While along the lip of the bay, monstrous fungal cathedrals rise under cover of darkness, replacing the old, familiar architecture. Skyline like a jagged wound.

Twenty years of civil war. Six years of the gray caps.

To Finch’s left, southwest: smudges of smoke, greasy and gray, above the distant mottled spectacle of the Spit, an island made of lashed-together boats. A den for spies. A sanctuary for the desperate and the lawless.

Beyond the Spit, the silhouette of the two living domes covering the detention camps. Broken by the smoke, hidden by debris. Built over a valley of homes. Built atop the remains of the military factories that had allowed the two great mercantile companies, House Hoegbotton and the invading House Frankwrithe & Lewden, to dream of empire, to destroy each other. And the city with them. Finch had fought for Hoegbotton. Once upon a time.

Between the domes, the fiery green glitter and minarets of the Religious Quarter, occupied by the remnants of native tribes. Adapting. Struggling. Destined someday to be wiped out. He can see the exposed crater at the top of the Truffidian Cathedral. Cracked. All the prayers let out. Nothing left.

To Finch’s right, on the north shore: the Hoegbotton & Frankwrithe Zone. Huge tendrils of reddish-orange fungus vein into the rocks lining the water. A green haze obscures any view of what might be left on the north shore. Six years ago, the HFZ had just been northern Ambergris: wild, yes, but not infected. Then, under sustained attack by the gray caps, the rebel army had retreated there. So much heavy armor, munitions, and ordnance had gone in, along with twenty thousand soldiers, that it is hard for Finch to believe all of it could just vanish or molder. Yet, apparently, it had. They’d gone in and the gray caps had created the Zone around them. Only the rebel commander they called the Lady in Blue and some of her soldiers had escaped the trap.

Once, the HFZ had grown in size every day. Now, it has stopped, covers about ten square miles. Almost every citizen can see it. For all the good that did. Will the rebels return? is the question everyone asks, even now. When the wind is strange—gusting this way and that without purpose—great glittering particles from the north drift orange and purple and blue across the bay into Ambergris. Even the gray caps don’t enter the HFZ except by proxy. Content to let the remnants of the rebels wander through a toxic fungal stew, goes the theory. Almost like another camp, without fences or guards.

Except, no one comes out of the HFZ.

Beyond the towers, beyond the bay, the far shore of the River Moth. Distant. Unattainable. Beyond that, although Finch can’t see it, just feels it: the eastern-most edge of the Kalif ’s empire, the Stockton Commonwealth to the south, the Morrow Protectorate to the north. Between them and Finch: security zones. Blockades. Set up by the surrounding countries. All three as determined as the gray caps that no one gets out of Ambergris. Even as they send in their spies to steal the city’s secrets.

Finch turns away from the window. It leaves him sad and cold and frightened. The towers especially. What will happen when the gray caps have finished them?

A view like that could drive a person mad.

3

“When the time comes, right, Finch?”

Back at the station, which used to be Hoegbotton & Sons’ headquarters. High ceilings. Hints of gold leaf and mosaic. Dull light from tiny round windows set in rows across both side walls. A tortured light that never gave any hint of the weather outside. Sometimes in the early morning and late afternoon they had to use old lanterns. The chandeliers had been ripped out long ago.

Back at his desk with the other detectives. The must of fungal rot from the green strip of carpet running from the front door down the middle. The whole back of the room hidden by a curtain. Smell of bad coffee from the table that also housed their only typewriter. Shoved up against the far wall. Next to the holding cell.

Ten desks. Seven detectives. Skinner, Gustat, Blakely, Dapple, Albin, and Wyte furiously scritching away on their notepads with sharp pencils. Some on the phone. All of them like schoolboys in an incomprehensible class. None of them likely to ask questions of the teacher.

Only a weak hello when Finch had walked in. Too much effort. Not yet over the paranoid morning jitters. Ever more difficult to know what to say. How to act. They all assumed the gray caps spied on them. Difficult to remember all day long. Especially when strange things happened with just enough irregularity to make them think that was the last time. The air pungent with old and new sweat. Laced with some underlying funk that was almost sweet.

Albin, just off the phone, out of the corner of his mouth: “I’m not risking my life for a lost dog. Too many Partials there. Besides, it’s an old Hoegbotton neighborhood.” Albin, the Frankwrithe & Lewden man. Finch might’ve shot at him back during the war. Former scientist. One of the few not killed by the gray caps or snatched by foreign powers in the chaos of the Rising.

Finch’s mood had soured on the way back to the station. A tortuous route. The gray caps had banned bicycles and motored vehicles four years ago. Too many suicide bombings by rebel sympathizers. Not much fuel anyway, and no one outside the city willing to resupply, even on the black market. Too dangerous. And few alternatives since the horses had been eaten long ago.

Instead, makeshift bridges over the canals. Through a sector where a lot of gray cap buildings had gone up, scrambling the landscape. Changes didn’t correspond to any map. Sliced through existing apartment complexes, divided or blocked streets. Displayed an arrogance about the way things had been and were now that angered Finch.

Then a mob to avoid at the corner of Albumuth and Lake, when he’d almost made it back. One of the huge blood-red drug mushrooms hadn’t yet released the morning ration. Not Finch’s problem. But the addicts were mad. They wanted their fix. Wanted out. They stood beneath the slow-breathing dead-white gills waiting for the purple nodules that also fed them. Wanted oblivion. A nice trip into waves of light and a past that didn’t include dead bodies and nightmares.

Maybe someday he’d join them. Instead, another rickety bridge over another canal. Had looked down at his frowning reflection in the silver-gray water and hadn’t recognized it. Broad shoulders. Still muscular but losing some of it. Too much alcohol. Not enough nutrients in the gray caps’ food. The man lingering in the water seemed at least forty-five, not forty. The hooded eyes. The paleness of the face. Wavery. Indistinct. Never in focus.

“When the time comes, right, Finch?”

“Sure, Wyte,” Finch said. “When the time comes.”

“You’ll know what to do.” The voice, once so deep and gravelly, had changed since Finch had first met Wyte. Become soft and liquid, lighter yet thicker.

“I’ll know what to do.”

The ritual conversation.

Ritual had a purpose. Ritual cordoned off fear. Ritual made the abnormal ordinary. The memory hole beside each of the desks. The deep green vein running the length of Wyte’s arm. Pushing up ridgelike against the fabric of Wyte’s long sleeve. Like the green carpet leading back to the curtains and what lay beyond.

Finch took his gun from its holster. Recoiled from the touch of the grip.

“For Truff’s sake,” Finch said. Laid it on his desk with a squelch.

The gun had been issued by the gray caps. Dark green exoskeleton, soft interior. Its guts stained his hand. Reloading didn’t seem like an option. It had been seeping a lot lately.

“I wonder if it’s dying on me,” Finch said. To Wyte, who sat at the desk to his left.

Should I have been feeding it?

Wyte grunted. Reflexively writing up reports on nothing in particular. Lost husbands. Unidentifiable corpses. Vandalism. Finch had cases, too, but nothing that couldn’t wait.

“Hate these things,” he said, again to Wyte. Again, to indifference.

Heard Blakely muttering to Gustat: “. . . they’re saying that we’re addicted to a special mushroom that grows out of our brains.” Gustat chuckled but it wasn’t funny. Rumors could get a detective killed by some desperate citizen. Any excuse that didn’t slip through the fingers.

Finch rummaged in a drawer. Found a worn handkerchief. It predated the war. He’d gotten it from an expensive clothing store further up the boulevard. Didn’t know why he kept it. Luck? Grimacing, he picked up the gun with the handkerchief. Shoved the thing into a space under his desk. Next to the box with the ceremonial sword his father had given him. Brought back from the Kalif’s empire twenty years before. Wrapped in cloth. Finch could always get to it in a pinch. Made him feel perversely safer knowing it was there. In its gleaming scabbard.

“I’d rather get shot than use that gun,” Finch said, too loud. Not sure if he meant it.

Gustat and Blakely, joined at the hip, looked up, glared. Both had a flushed look. Like they’d been drinking.

“Shut up, Finch,” Blakely said.

“Yeah, shut up,” Gustat echoed. Fiercely.

This caused Dapple to bring a case file so close to his eyes it hid his face. Dapple was the worst of them. He’d been an artist once. Landscape painter. Watercolors. Popular with the tourists. No market for that now. No landscapes to speak of that you could spend hours painting without taking a bullet for your troubles. Sure to become a druggie, or a creature of the gray caps in his cringing way. At least Gustat and Blakely, even though they annoyed Finch, still had their wits about them.

Almost as if to cover for Finch, Wyte asked, “So, Finchy, just how bad was it?” “Finchy” sounded closer to his real last name, so Wyte often called him that. To avoid slipping up.

Finch turned toward Wyte. Hadn’t wanted to. No telling what he looked like.

Wyte: a tall man, late forties, with a handsome face, powerful shoulders and chest. Tattered olive suit. Eyes gray. A spark of green colonizing the brown of each pupil. Right temple: a purple birthmark that hadn’t been there yesterday. Smelled of cigarette smoke to cover the stench of mushrooms. Even though cigs were hard to come by. Once, he could have entered a crowded bar and all the women would have found a way to stare at him.

“A double,” Finch said. “In an abandoned apartment. One gray cap. One male human.” Then told Wyte the rest.

“Dancing lessons gone terribly wrong,” Wyte said. His grin only manifested on the left side of his mouth.

Skinner, next to Wyte, hazarded a snicker. But Skinner snickered at everything. Finch didn’t find it funny. He was still seeing the bodies. Skinner expressed too much zeal pursuing cases that involved the rebels. Why hadn’t Skinner become a Partial?

“This is nothing good, Wyte.” Good equaled will go away quickly.

This could linger.

Wyte, as if realizing his mistake: “Do you want me to take the memory bulbs?”

“No thanks.”

Who knew what a memory bulb would do to Wyte in his state? Finch didn’t want to find out. The late Richard Dorn had sat at his desk for nine months after the gray caps had forced him to eat a memory bulb despite his wasting disease. Dead. Turning into a tower of emerald mold. The desk sat in a corner now, abandoned, a smudge on the seat of the chair.

Worse for suspects kept in the holding cell. Bring in a thief, do the paperwork, then the gray caps decided. Attempted murder? Might be disappeared by morning. Or sent to the camps. Or let off with a fine. The guy Blakely had brought in the other day was still there. Slumped in a corner. Clearly thought his life was over.

Never bring anyone in unless you have to. Unless you’re certain.

“Are we in trouble on this one?” Wyte asked. Black patch on his neck, slowly moving. Nails a faint green. A whiff of something toxic.

Not the same kind of trouble.

Finch shrugged. “Who knows?” A routine call could turn into disaster. A disaster could go away overnight.

Wyte leaned back in his chair, hands behind his head. Red stains on the shirt’s underarms.

Finch had known Wyte for more than twenty years. They’d fought in the wars together. Known the same people before the Rising. Played darts at the pub. Had drinks. Sudden gut-punching vision: of his girlfriend back then, a slender brunette who’d worked as a nurse. Laughing at some joke Wyte had made one night, the days of Comedian Wyte now long past except for the occasional flare-up that just made it worse.

Some cosmic mistake or cruelty, to work cases together when Finch had once worked for Wyte as a courier for Hoegbotton. Each a reminder to the other of better times. Since then, Wyte’s wife Emily had left him. He’d taken up in a crappy apartment just north of the station. Never saw his two daughters. They’d been smuggled out to relatives in Stockton before the Rising. Finch couldn’t work out how old they might be now.

Someday Wyte will be a silhouette on the horizon. Someone familiar made distant.

And Wyte sensed it.

“You can help with the fieldwork going forward, Wyte,” Finch said. If you don’t become the fieldwork.

“No problem. Be happy to.”

“I’ll put my notes in order,” Finch said, “and after I use the memory bulbs, we’ll start in on it. Tomorrow.”

Wyte wasn’t listening anymore. Gaze far away. Disengaged. Apocalyptic thoughts? Or maybe he was just registering the inside of the building. They all conducted an unspoken war against the station. It tried to make them forget its strangeness. They tried not to forget.

Finch turned back to his desk and started sorting through the mess. Hadn’t organized it in a week. Hadn’t had the energy.

Mirror. Pills to protect against infection. Spore mask for purified breathing. Writing pad. Pencils. Telephone. Broken telephone. Folders on open crimes. Folders on closed crimes. Paper clips across the bottom of drawers. A list he’d made of complaints from people who had called him, thinking he could help. Usually he couldn’t.

Maybe once, early on, he had convinced himself he could do some good, sometimes even imagined he was a mole, getting close so he could strike a blow. Imagined he was in it to defend Ambergris from the enemies that surrounded it. Imagined he was protecting ordinary citizens.

But the truth was he’d been tired, had stopped caring. Broken down from too much fighting, too many things connected to his past. And when that spark, that impulse, had returned, it was too late: he was trapped.

“I’m not a detective.”

Heretic: “You’re whatever we want you to be, now.”

If he just left one day, what would happen to Wyte? To his other friends? To Sintra?

And: Did they know about Sintra?

Nothing seemed missing from his desk. Still, a good idea to take stock. Lots of things disappeared during the night, or were replaced by mimics. More than one detective had screamed, picking up a pencil that was not a pencil. Finch took out the piece of paper he’d found in the dead man’s hands. Placed it in front of him. What could the words mean? Finch took out a writing pad, scrawled

Never Lost.

Bellum omnium contra omnes

across the top. Stared at the strange symbol. It looked oddly like a baby bird to him.

Randomly ripped from a book to write on? Or something more? Abandoned the question. Wrote:

two bodies

fell

Thought about the Partial, daring to contradict Heretic. Heretic’s secret amusement. What did that mean? At least he knew what Heretic on the scene meant: the gray cap must suspect the case had some connection to the rebels and their elusive commander, the Lady in Blue. She who was now larger than the city and yet not of the city. Most saw her hand in any act that seemed to cause the gray caps grief. Although such acts of resistance seemed rarer and rarer. Some thought she didn’t exist. Or was dead.

The trapped rebel soldiers. The Lady in Blue.

Was the fate of either better or worse than his?

* * *

Finch sees again, back across six long years, the columns of tanks and infantry in retreat, traveling through the city toward the north. Recognizes with hindsight that the path they took had been chosen by the gray caps. Forced by the rising water.

Distant explosions had split the air as the gray caps attacked stragglers at the end of the column. Even then, small-arms fire no longer registered with Finch unless it was close by.

Despite the risk, many people had come out to watch the rebels. From the roadside. From balconies. Peering out of windows reinforced with metal bars. To bear witness to the rumbling tread of the tanks. To remember the faces of the troops: pale and dark, old and young and middle-aged. Beneath green helmets with the intertwined H&S/F&L insignia that rankled so many. Armed with automatic weapons, bayonets, knives. Most in uniform. Many damaged. A welter of bandages on heads, legs, arms, that hid evidence of strange fungal wounds.

One man’s face held Finch’s attention. Salt-and-pepper beard, creases in his forehead, wrinkles that made him look as if he were squinting. A red patch on his cheek. Body slumped, then tensed, against the lurching of the tank. A gaunt hand clutching his Lewden rifle, knuckles prominent. Gaze turned forward, as if unwilling to acknowledge the present.

Which had made Finch realize again that these men and women leaving, they were the same ones who had fought one another during more than three decades of the War of the Houses, broken only by armistices, cease-fires, and the dream of empire. The ones who had brought ruination upon Ambergris in so many ways before the Rising.

Yet they were still from Ambergris, of Ambergris, and even Finch felt it in his chest, Wyte standing there beside him with his Emily. Almost as if Ambergris itself was retreating, leaving behind only ghosts and children. But also leaving a perverse giddiness. A sense of celebration at seeing such a mighty force. The retreat portrayed as a new beginning. The lull before the launching of a great offensive.

Even the tanks were part of Ambergris. They’d come out of the eighty-year-old metal deposits found in eastern Ambergris that had catapulted the city out of the past but not yet into the future.

Rebel tanks had two turrets: one pointed ahead, one unseen beneath that pointed at the ground. Specially built to open up and deliver bombs to underground gray cap enclaves. Once, their rough syncopated song had been heard all over the city. Juddered through the ground into the walls of buildings and tunnels alike. Like a kind of defiant echoing growl.

In retreat, though, it was the singing of the troops as they left that Finch heard, their voices ragged over the rumble of the tanks. Patriotic songs composed long centuries before. A refrain that had started as a prayer by the Truffidian monks.

Holy city, majestic, banish your fears.

Arise, emerge from your sleeping years.

Too long have you dwelt in the valley of tears.

We shall restore you with mercy and grace.

City of wounds. City of wounding. For a moment, Finch had felt the urge to climb up onto one of the tanks, to join them in what was then the wilderness of North Ambergris. But Finch wasn’t one of them. He’d had no officer to report to. Had bought his own weapon. Off the books, off the record. An Irregular, fighting alongside other Irregulars in his neighborhood. Defending their sisters, brothers, parents, and neighbors against the invaders.

After the last tank had rumbled past, Finch had gone back with Wyte and Emily. To await the next thing. No matter what it might be. The need to work. To eat. To have shelter. People were already telling themselves things might still be better under the gray caps than during the War of the Houses, at least. Joked about it. Like you might about a passing storm.

Waiting it out at Wyte’s house. By candlelight. Drinking. Laughing nervously. Trying to forget. Finch’s father dead almost two years.

Just after midnight: a sound like a giant flame opening up and then winking out. A devastating whump, as of something hitting the ground or rising from it. When they looked outside, they’d seen a dome-like haze above the north part of the bay. Green-orange discharge like sunspots. They’d just watched it. Watched it and not known what to say. What to do. Barricaded the house. Spent the rest of the night with weapons within reach.

In the morning, a paralyzing horror. Across the bay, when they slipped out through back alleys to get a clear view: the seething area that became known as the HFZ, and no sign of anyone alive. No sign of the tanks. No messages from the rebel leadership.

Thought but not said: Abandoned. Gone. On our own.

Then the realization, as the gray caps began to appear in numbers in the streets, and as their surrogates the Partials began to help occupy the city, that the war was over for now. That each citizen of Ambergris would need to make some kind of peace with the enemy.

Always with the hope sent out across the water toward the HFZ: that the tanks, the men, might come back. Might re-emerge. That the rebels were not dead. Destroyed.

Lost.

4

Mid-afternoon. A soft, wet, sucking sound came from the memory hole beside his desk. Finch shuddered, put aside his notes. A message had arrived.

Some detectives positioned their desks so they could see their memory holes. Finch positioned his desk so he couldn’t see it without leaning over. Tried never to look at it when he walked into the station in the morning. Still, the memory hole was better than the dead cat reanimated on Skinner’s doorstep, message delivered in screeched rhyming couplets. Or the mushroom that walked onto Dapple’s desk, turning itself inside out. To reveal the message.

Exhaled sharply. Peered around the left edge of the desk. Glanced down at the glistening hole. It was about twice the size of a man’s fist. Lamprey-like teeth. Gasping, pink-tinged maw. Foul. The green tendrils lining the gullet had pushed up the dirty black spherical pod until it lay atop the mouth.

Finch sat up. Couldn’t see it. Just heard its breathing. Which was worse.

The gray caps always called them “message tubes,” but the term “memory hole” had stuck. Memory holes allowed the detectives to communicate during the day with their gray cap superiors. Finch had no idea if the memory holes were living creatures or only seemed alive. Fluid leaked out of them sometimes.

Once, impulsive, Finch had crumpled up the wrapper around the remains of his lunch and shoved it down the hole. Lived in fear the rest of the day. But nothing had happened. When he’d thought about it since, it had made him laugh. Heretic, down there, hit in the head with a piece of garbage. Maybe cursing Finch’s name.

Now Heretic’s message vibrated atop writhing tendrils.

Finch leaned over. Grabbed the pod. Slimy feel. Sticky.

Tossed the pod onto his desk. Pulled out a hammer from the same drawer where he kept his limited supply of dormant pods. Split Heretic’s pod wide open. Spraying slime.

Beside Finch, Wyte winced, got up for some coffee.

Disgusted, or was it too close to home?

“There’s no pretty way to do it, my friends,” Finch called out. “Just look away.” No one acknowledged him this time. Too usual. Even Finch’s refrain.

In amongst the fragments: a few copies of a photograph of the dead man, compliments of the Partial.

And a message.

Pulsing yellow. An egg of living paper. He pulled the egg out of the shattered pod. Began to massage it until it spread out flat. Kept spreading, to Finch’s surprise. Then began to unspool. Like a long, wide tongue. And kept on growing.

That was unusual enough for the other detectives to gather round.

“What in the hell is that?” Blakely asked, Gustat beside him. Dapple shyly peeked over Blakely’s shoulder. Albin and Skinner were out on a call or they’d have been right there too. Anything to waste time.

“Looks like Heretic’s given you a long to-do list,” Gustat said. Too young to have known anything but war and the Rising.

Finch said nothing. By now, the pliant paper had grown to drape itself over both sides of Finch’s desk, sliding into his lap. Clutched at it. Saw the rows of information in the reed-thin, spidery print common to gray cap documents. He let out a long, deep breath.

“It’s the records of everyone who ever lived in the apartment of the double murder I was at this morning. Going back . . .” He checked as the paper finished unspooling. “Going back over a century. More.”

Pulse quickening. How am I supposed to investigate that?

MORDEN, JONATHAN, OCCUPANCY 3 MONTHS, 2 DAYS, 11 MINUTES, 5 SECONDS—WORKED IN FOOD DISTRIBUTION IN THE CAMPS . . .

WILDEN, SARAH, OCCUPANCY 8 MONTHS, 3 DAYS, 2 MINUTES, 45 SECONDS—NEVER LEFT THE APARTMENT EXCEPT FOR GETTING FOOD. HAD THREE CATS. LIKED TO READ . . .

* * *

A sudden panic. Smothered by the past. Lost in it.

Tried to get a grip. Wadded the paper up, pocketed the photographs. While the other detectives gave out nervous laughs. Returned to their desks. Frightened again.

No one wanted this kind of case.

A sudden anger rose in Finch. Did Heretic really think that this list would be helpful? It was scaring the shit out of him.

Wyte had been standing behind the others, holding his coffee mug. Loomed now like an actor from backstage, suddenly revealed.

“A lot of information,” Wyte said.

Finch glared at him. Hands splattered with yellow and green. “Find me a towel.”

Wyte put down his coffee, rummaged in a desk drawer.

SILVAN, JAMES, OCCUPANCY 15 MONTHS, 3 DAYS, 1 HOUR, 50 MINUTES, 2 SECONDS—COLLABORATOR WITH A SPLINTER REBEL FACTION . . .

HUGHES, SHANNA, OCCUPANCY 1 MONTH, 2 WEEKS, 3 DAYS, 10 MINUTES, 35 SECONDS—KILLED BY A FUNGAL BOMB . . .

“Maybe they got it from the old bureaucratic quarter?” Wyte whispered out of the side of his mouth as he leaned over to give Finch the towel. Smell of sweat mixed with something sweeter. “Maybe they just copied it down?” Returning to his desk, receding into the background.

“It’s half-encrypted with their symbols, Wyte,” Finch said. Tried to correct for the disdain in his voice. “It contains surveillance information. They collected it themselves.”

From underground. Using a million spore-eye cameras. Somewhere, he knew, in one of a series of images captured by the gray caps: evidence of his past that Heretic didn’t know about. Finch as a Hoegbotton Irregular fighting against Frankwrithe & Lewden in the War of the Houses. Finch standing side by side with F&L soldiers against the gray caps before they Rose. What he’d done.

Except the gray caps didn’t have the time to pore over that many images unless given a good reason. And Finch hadn’t. Only Wyte knew the truth.

GILRISH, MEGHAN, OCCUPANCY 10 MONTHS, 3 WEEKS, 6 DAYS, 14 HOURS, 15 MINUTES, 6 SECONDS—OWNER OF A GROCERY STORE . . .

BARRAN, GEORGE, OCCUPANCY 2 YEARS, 1 WEEK, 5 DAYS, 7 MINUTES, 18 SECONDS—DIED OF OLD AGE . . .

Finch stared at the first rows of names on the paper. The sheer density of information defeated him.

Kept thinking about the bodies. Saw them lying there on the floor of the apartment. They dropped in out of thin air.