Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

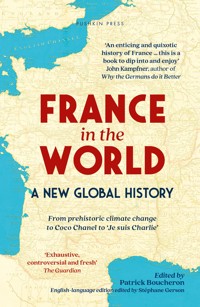

A fresh, provocative history that renews our understanding of France in the world through short, incisive essays ranging from prehistoric frescoes to Coco Chanel to the terrorist attacks of 2015.Bringing together an impressive group of established and up-and-coming historians, this bestselling history conceives of France not as a fixed, rooted entity, but instead as a place and an idea in flux, moving beyond all borders and frontiers, shaped by exchanges and mixtures. Presented in chronological order from 34,000 BC to 2015, each chapter covers a significant year from its own particular angle - the marriage of a Viking leader to a Carolingian princess proposed by Charles the Fat in 882, the Persian embassy's reception at the court of Louis XIV in 1715, the Chilean coup d'état against President Salvador Allende in 1973 that mobilised a generation of French left-wing activists.France in the World combines the intellectual rigour of an academic work with the liveliness and readability of popular history. With a brand-new preface aimed at an international audience, this English-language edition will inspire Francophiles and scholars alike.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1381

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Patrick Boucheron is a French historian and broadcaster. He previously taught medieval history at the École normale supérieure and the University of Paris-Sorbonne, and is currently a professor of history at the Collège de France. He is the author of twelve books, including Machiavelli: The Art of Teaching People What to Fear (Pushkin, 2020), and the editor of five, including France in the World, which became a bestseller in France.

Stéphane Gerson is a cultural historian and a professor of French Studies at New York University. He has won several awards, including the Jacques Barzun Prize in Cultural History and the Laurence Wylie Prize in French Cultural Studies. He currently directs NYU’s Institute of French Studies.

PRAISE FOR

France in the World

“A major work, exhaustive, controversial and fresh—and entirely relevant to Anglophone readers.” The Guardian

“An eclectic and forward-looking history…Patrick Boucheron and his merry band of historians have succeeded in putting more dynamic and inclusive republican visions of Frenchness back into the limelight.…their bracing scholarship looks set to shape the agenda of historical research and civic debate in France for years to come.” Times Literary Supplement

“A readable work of considerable scholarly interest” Financial Times

“After several decades of somnolence, academic history is a hit… [France in the World] marks the arrival of a new generation of historians, full of energy and élan.” Robert Darnton, New York Review of Books

“Unexpected, relevant, well done. A history of France that will count.” Le Point

“A historiographic landmark.” Le Monde des livres

France in the World

EDITED BY

Patrick Boucheron

WITH

Nicolas Delalande

Florian Mazel

Yann Potin

Pierre Singaravélou

ENGLISH-LANGUAGE EDITION

EDITED BY

Stéphane Gerson

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH BY

Teresa Lavender Fagan

Jane Kuntz

Alexis Pernsteiner

Anthony Roberts

Willard Wood

France in the World

A New Global History

Pushkin Press

A Gallic Book

Copyright © Éditions du Seuil, 2017

English translation copyright © Other Press, 2019

Originally published in 2017 as Histoire mondiale de la France

by Éditions du Seuil, Paris

This edition first published in 2021 by Gallic Books

12 Eccleston St, London SW1W 9LT

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention

No reproduction without permission

All rights reserved

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781805333920

Typeset in Fournier by Gallic Books

Printed in the UK by CPI (CR0 4YY)

Preface to the English-Language Edition STÉPHANE GERSON

Overture PATRICK BOUCHERON

EARLY STIRRINGS IN ONE CORNER OF THE WORLD

34,000BCE — Creating the World Deep inside the Earth FRANÇOIS BON

23,000BCE — Man Gives Himself the Face of a Woman FRANÇOIS BON

12,000BCE — Climate Unhinged and Art Regenerated BORIS VALENTIN

5800BCE — From the Plenitude of Eastern Wheat Fields JEAN-PAUL DEMOULE

600BCE — Marseille: A Greek Outpost in Gaul? VINCENT AZOULAY

500BCE — The Last of the Celts LAURENT OLIVIER

52BCE — Alésia: The Meaning of Defeat YANN POTIN

FROM ONE EMPIRE TO ANOTHER

48 — Gauls in the Roman Senate ANTONY HOSTEIN

177 — Eastern Christianity’s Eldest Daughter? VINCENT PUECH

212 — Romans Like the Rest MAURICE SARTRE

397 — St. Martin: Gaul’s Hungarian Patron Saint STÉPHANE GIOANNI

511 — The Franks Choose Paris as Their Capital MAGALI COUMERT

719 — Africa Knocks on the Franks’ Door FRANÇOIS-XAVIER FAUVELLE

800 — Charlemagne, the Empire, and the World MARIE-CÉLINE ISAÏA

THE FEUDAL ORDER TRIUMPHS

842–843 — When Languages Did Not Make Kingdoms MICHEL BANNIARD

882 — A Viking in the Carolingian Family? PIERRE BAUDUIN

910 — A Network of Monasteries ISABELLE ROSÉ

987 — The Election of the King Who Did Not Make France MICHEL ZIMMERMANN

1051 — An Early Franco-Russian Alliance OLIVIER GUYOTJEANNIN

1066 — Normans in the Four Corners of the World FLORIAN MAZEL

1095 — The Frankish East FLORIAN MAZEL

1105 — Troyes, a Talmudic Capital JULIETTE SIBON

1137 — A Capetian Crosses the Loire FANNY MADELINE

1143 — “The Execrable Muhammad” DOMINIQUE IOGNA-PRAT

FRANCE EXPANDS

1202 — Four Venetians at the Champagne Fairs MATHIEU ARNOUX

1214 — The Two Europes, and the France of Bouvines PIERRE MONNET

1215 — Universitas: The “French Model” ALAIN DE LIBERA

1247 — The Science of Water Management in Thirteenth-Century France JEAN-LOUP ABBÉ

1270 — Saint Louis Is Born in Carthage YANN POTIN

1282 — “Death to the French!” FLORIAN MAZEL

1287 — Gothic Art Imperiled on the Sea ÉTIENNE HAMON

1336 — The Avignon Pope Is Not in France ÉTIENNE ANHEIM

THE GREAT MONARCHY OF THE WEST

1347 — The Plague Strikes France JULIEN LOISEAU

1357 — Paris and Europe in Revolt AMABLE SABLON DU CORAIL

1380 — An Image of the World in a Library YANN POTIN

1420 — The Marriage of France and England YANN POTIN

1446 — An Enslaved Black Man in Pamiers HÉLÈNE DÉBAX

1456 — Jacques Coeur Dies in Chios MATTHIEU SCHERMAN

1484 — A Turkish Prince in Auvergne NICOLAS VATIN

1494 — Charles VIII Goes to Italy — and Loses the World PATRICK BOUCHERON

1515 — Whatever Led Him to Marignano? AMABLE SABLON DU CORAIL

1534 — Jacques Cartier and the New Lands YANN LIGNEREUX

1536 — From Cauvin to Calvin JÉRÉMIE FOA

1539 — The Empire of the French Language PATRICK BOUCHERON

1550 — The Normans Play Indians YANN LIGNEREUX

1572 — Saint Bartholomew’s Season PHILIPPE HAMON

1610 — The Political Climate in Baroque France STÉPHANE VAN DAMME

ABSOLUTE POWER

1633 — Descartes Is the World! STÉPHANE VAN DAMME

1659 — Spain Cedes Supremacy and Cocoa to France JEAN-FREDERIC SCHAUB

1662 — Dunkirk, Nest of Spies RENAUD MORIEUX

1682 — Versailles, Capital of French Europe PAULINE LEMAIGRE-GAFFIER

1683 — 1492, French-Style? JEAN-FRÉDÉRIC SCHAUB

1685 — France Revokes the Edict of Nantes, All of Europe Reverberates PHILIPPE JOUTARD

1686 — Siam: A Missed Opportunity ROMAIN BERTRAND

1712 — The Thousand and One Nights: Antoine Galland’s Forgery SYLVETTE LARZUL

1715 — Persians at the Court of Louis XIV THIERRY SARMANT

1720 — Law and Disorder FRANÇOIS VELDE

ENLIGHTENMENT NATION

1751 — All the World’s Knowledge JEAN-LUC CHAPPEY

1763 — A Kingdom for an Empire YANN LIGNEREUX

1769 — The World’s a Conversation ANTOINE LILTI

1771 — Beauty and the Beast: An Opéra Comique at the Court of France MÉLANIE TRAVERSIER

1784 — Sade: Imprisoned and Universal ANNE SIMONIN

1789 — The Global Revolution ANNIE JOURDAN

1790 — Declaring Peace on Earth SOPHIE WAHNICH

1791 — Plantations in Revolution MANUEL COVO

1793 — Paris, Capital of the Natural World HÉLÈNE BLAIS

1794 — The Terror in Europe GUILLAUME MAZEAU

A HOMELAND FOR A UNIVERSAL REVOLUTION

1795 — “The Republic of Letters Shall Give Birth to Republics” JULIEN VINCENT

1798 — Conquest(s) of Egypt JULIEN LOISEAU

1804 — Many Nations under One Code of Law JEAN-LOUIS HALPÉRIN

1804 — The Coronation of Napoleon Bonaparte THIERRY SARMANT

1808 — Napoleon and Spain: An Atlantic Affair GENEVIÈVE VERDO

1815 — Museums of Europe, Year Zero BÉNÉDICTE SAVOY

1816 — The Year without a Summer JEAN-BAPTISTE FRESSOZ AND FABIENLOCHER

1825 — Rescuing Greece HERVÉ MAZUREL

1832 — France in the Time of Cholera NICOLAS DELALANDE

1840 — Utopian Year FRANÇOIS JARRIGE

1842 — Literature for the Planet JÉRÔME DAVID

1848 — Paris, Revolution Ground Zero QUENTIN DELUERMOZ

1852 — Penal Colonization JEAN-LUCIEN SANCHEZ

GLOBALIZATION IN THE FRENCH STYLE

1858 — A Land of Visions GUILLAUME CUCHET

1860 — The Other Free Trade Country DAVID TODD

1863 — “Algeria Shall Be an Arab Kingdom” CLAIRE FREDJ

1869 — The Inauguration of the Suez Canal VALESKA HUBER

1871 — Local Revolution, Global Myth QUENTIN DELUERMOZ

1875 — Measuring the World NICOLAS DEIALANDE

1883 — From the Zambezi to the Corrèze, a Single World Language? PIERRE SINGARAVÉLOU

1889 — Order and Progress in the Tropics MAUD CHIRIO

1891 — Pasteurizing the French Empire GUILLAUME LACHENAL

1892 — “Nobody Is Innocent!” JENNY RAFLIK

1894 — Dreyfus, a European Affair ARNAUD-DOMINIQUE HOUTE

1900 — France Hosts the World CHRISTOPHE CHARLE

1903 — French Science Enlightened by Radioactivity NATALIE PIGEARD-MICAULT

MODERNIZING IN TROUBLED TIMES

1907 — A Modern Art Manifesto LAURENCE BERTRAND DORLÉAC

1913 — A Promenade for the English SYLVAIN VENAYRE

1914 — From the Great War to the First World War BRUNO CABANES

1917 — The View from New Caledonia ALBAN BENSA

1919 — Two World-Changing Conferences EMMANUELLE SIBEUD

1920 — “If You Would Have Peace, Cultivate Justice” BRUNO CABANES

1921 — Chanel — A Woman’s Scent for the World EUGÉNIE BRIOT

1923 — Crossroads of Exile ANOUCHE KUNTH

1927 — Naturalizing CLAIRE ZALC

1931 — Empire at the Gates of Paris PASCALE BARTHÉLÉMY

1936 — A French New Deal NICOLAS DELALANDE

1940 — Free France Emerges in Equatorial Africa ERIC JENNINGS

1940 — Lascaux: World Art and National Humiliation YANN POTIN

1942 — Vél’ d’Hiv’–Drancy–Auschwitz ANNETTE WIEVIORKA

1946 — The Yalta of Film ANTOINE DE BAECQUE

1948 — Universal Human Rights DZOVINAR KÉVONIAN

1949 — Reinventing Feminism SYLVIE CHAPERON

1953 — “Our Comrade Stalin Is Dead” MARC LAZAR

1954 — Toward a New Humanitarianism AXELLE BRODIEZ-DOLINO

1958 — Algiers and the Collapse of the Fourth Republic SYLVIE THÉNAULT

1960 — The End of the Federalist Dream and the Invention of Françafrique JEAN-PIERRE BAT

LEAVING THE COLONIAL EMPIRE, ENTERING EUROPE

1961 — “The Wretched of the Earth” Mourn Frantz Fanon EMMANUELLE LOYER

1962 — Jerusalem and the Twilight of French Algeria VINCENT LEMIRE

1962 — Farming: A New Global Order ARMEL CAMPAGNE, LÉNA HUMBERT AND CHRISTOPHE BONNEUIL

1965 — Astérix among the Stars SEBASTIAN GREVSMÜHL

1968 — “A Specter Haunts the Planet” LUDIVINE BANTIGNY

1973 — The Scramble for Oil in a Floating World CHRISTOPHE BONNEUIL

1973 — The Other 9/11 MAUD CHIRIO

1974 — Curbing Migration ALEXIS SPIRE

1983 — Socialism and Globalization FRANÇOIS DENORD

1984 — “Michel Foucault Is Dead” PHILIPPE ARTIÈRES

TODAY IN FRANCE

1989 — The Revolution Is Over PATRICK GARCIA

1992 — A Very Muted “Yes” LAURENT WARLOUZET

1998 — France and Multiculturalism: “Black-Blanc-Beur”STÉPHANE BEAUD

2003 — “This Message Comes to You from an Old Country…” LEYLA DAKHLI

2008 — The Native Land in Mourning ALAIN MABANCKOU

2011 — Power Stripped Bare NICOLAS DELALANDE

2015 — The Return of the Flag EMMANUEL LAURENTIN

Index

Off the Beaten Track

PREFACE

TO THE ENGLISH-LANGUAGE EDITION

Stéphane Gerson

This is an urgent book.

The world in which we live is saturated with history — in reenactments, themed video games, cable shows, books about our national history (or at least some aspects of it). And yet, this public appetite is often fed by media-savvy journalists or politicians and ideologues whose fast-paced, anecdote-rich sentimental sagas meld fact and fiction while appealing to the emotions. Rarely do they engage with the past in a serious, critical manner. For this, for guidance on how to situate ourselves in an unstable world, we need historians — not only in our universities, but in the public realm as well.

In 1931, the president of the American Historical Association, Carl Becker, reminded his colleagues that their “proper function is not to repeat the past but to make use of it, to correct and rationalize for common use Mr. Everyman’s mythological adaptation of what actually happened.” In a more recent History Manifesto (2014), Jo Guldi and David Armitage urged their fellow historians to explain large historical processes and small events in terms all of us can understand. This task, they said, should not be farmed out to economists and journalists. History has “a power to liberate” — from, for example, false notions about climate change or national destiny.

While some historians concur, others are reticent, or else too timid to write in a new key. Current attacks on truth and expert knowledge make this a pressing matter — and not just in the US. Consider France. For a long time, French historians were public intellectuals, making their voices heard in books, magazines, newspapers, and later on TV and radio. From Jules Michelet in the nineteenth century to Jacques Le Goff and Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie after World War II, and later Michelle Perrot, historians rendered their craft topical and enthralling for a wide readership.

But things have changed in recent decades. Book sales have declined; the mass media have grown less welcoming; academic historians have been accused of writing a convoluted history, neglecting chronology, and in some cases not loving their country enough. Journalists, essayists, and even film actors have filled this void in recent years, appointing themselves curators of the roman national, a national narrative with which French citizens can identify. The mournful, nostalgic story they typically tell is one of loss and decline, in which national identity must battle immigration, multiculturalism, Islam, feminism, and “declining” school standards. Salvation rests upon a return to imagined origins.

In 2017, a collective of French historians responded to these developments by publishing a non-nationalist history of the nation. Histoire mondiale de la France, or France in the World: A New Global History, makes a deceptively strong statement: historians have a distinctive contribution to make to our public debates and collective self-understanding. The book was an instant success, “the literary phenomenon of the year” (in the words of one newsmagazine), with more than 110,000 copies sold. In newspapers and magazines, on TV and radio, commentators celebrated a work that, as one of them put it, “is good news for those among us who yearn for new pathways into the past of our dear old country.” Fellow historians agreed, lauding an “immense collection of knowledge and analysis” whose wide-ranging curiosity made it, they said, an “enemy of the tragic.” In other countries, France in the World provided a blueprint for histories that, while investigating the past, unravel contemporary notions we deem self-evident. Similar global histories of Italy, the Netherlands, Catalonia, Flanders, and Spain quickly followed — or will in the near future.

The book’s lead editor, Patrick Boucheron, is a specialist in late-medieval Italian history, a professor at the prestigious Collège de France, and the editor of, among other books, Histoire du monde au XVe siècle (History of the World in the Fifteenth Century). He also belongs to a generation of French historians who seek to recover the public role, the civic engagement of their predecessors — not as grand intellectuals who, like Jean-Paul Sartre, share their views on all issues, but rather as measured commentators who bring their expertise to bear on specific questions. In order to reach a broader readership, these historians are consulting on historical TV shows, participating in theater festivals, and writing threads about history on Twitter. They are also experimenting with graphic novels, memoirs, and other unconventional forms of historical writing.

France in the World is one such experiment, bold in its scope and its commitment to scholarship coupled with freedom and formal creativity. Patrick Boucheron and his four coeditors made several key decisions at the outset. They organized the book as a series of essays about 146 dates in the history of France, each one distilling the latest scholarship while avoiding jargon and footnotes. Ranging from 34,000 BCE to 2015, these essays either explore turning points, such as Charlemagne’s coronation in 800 or the May 1968 civil unrest, or else delve into less momentous yet still telling events, such as the draining of a Languedoc pond in 1247. “Some rare events are like glimmers of light in the darkness,” Antony Hostein writes in his essay on Gauls in the Roman Senate (48 CE). “Illuminated by a few extraordinary accounts telling of singular lives and exploits, they reveal truly significant historical occurrences.”

The editors invited dozens of historians to write these essays, and few turned them down. The members of this collective represent a multitude of historical specialties, from the Middle Ages to the contemporary era, archaeology to technology, law to finance, gender to cinema. The book thus invites readers to learn about states, wars, expeditions, and peace treaties, as we would expect, but also about diseases and penal colonies, canals and promenades, fashion and perfume, museums and best sellers, swindles and engineering feats. Generals and politicians, aristocrats and bureaucrats comingle with cave dwellers and textile traders, novelists and feminists, soccer players and philosophers, vagrants and immigrants, all of them protagonists in a variegated history.

The editors provided the contributors with considerable latitude, inviting them to select their own points of departure. History does not correspond to a single outlook, an all-knowing stance, pinpointing truth from its lofty heights. Instead, these multiple perspectives make it clear that the past becomes history through the questions we pose and the methods we fashion. “[I]t is not historical material that shapes interpretations,” Pierre Monnet writes in his essay on the 1214 Battle of Bouvines, “but rather the historian’s questions that shape historical material. And these questions are far from exhausted.” France in the World opens up the historian’s workshop, drawing attention to craft and sources, to doubts and choices and the debates that advance knowledge.

The editors also urged the contributors to embrace a free, welcoming language, to avail themselves of “all the resources of storytelling, of analysis, contextualization, exemplification.” Patrick Boucheron has long pushed his fellow historians toward “audacity and creativity and perhaps also greater confidence in the powers of language.” Literary, even poetic historical writing opens up common language by unsettling what seems familiar and breathing life into “the textures of the past.” And so, the essays in France in the World take different forms: narrative descriptions, direct addresses to the reader, slightly ironic glosses, political asides on the past and the present.

I want to emphasize the plural — resources, powers, contours of language — for the editors grant us — the readers — as much freedom and, therefore, as much trust and responsibility as they do the contributors. They encourage us to trace our own itineraries across the past, to read diagonally through time and the conventional periods that govern our vision of history. Begin at the beginning, or in the middle if you prefer, and see where you end up. By neglecting key dates (say, the 1916 Battle of Verdun) and adding others that may seem inconsequential, by granting the same number of words to Coco Chanel as to Charlemagne, they are telling us that all planes of history are equally revealing, that all historical actors deserve attention. Hierarchies exist, of course, but do not expect to find one ready-made in this book. It falls upon us, as attentive readers and critical thinkers, to create meaning out of the apparent chaos of history.

France in the World is thus a political book if one understands politics not as the partisan reading of evidence or the explicit embrace of party positions, but instead as the deployment of reason against despair. The book is also political in its central question: What does it mean to belong to a nation in our globalized yet nationalistic world?

This question carried particular resonance during the book’s gestation in 2015 and 2016 — so much so that France in the World may already be read as a historical artifact, a trace of the contemporary past, a source for future histories of our troubled times. France’s annus horribilis of 2015 began with terrorist attacks in several Parisian locations, including the offices of the satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo and a kosher grocery store, and ended with yet bloodier assaults on the Bataclan concert hall and other targets. On January 11, dozens of heads of state traveled to Paris to reaffirm their commitment to political values — the rights of man, freedom of expression — that have long been linked to France. This gathering raised a new set of questions: Does France still live up to these ideals? What exactly does the country represent nowadays? What do the French want it to represent at this complicated juncture in the country’s history?

After all, the former global power has seen its stature and its political ambitions wither over the past century. France and its allies won World War I thanks to a US military intervention that forever altered the transatlantic balance of power. In 1940, the French Army’s debacle cost the country more than its honor and its republic: an authoritarian regime in Vichy collaborated with Hitler and persecuted Jews and others. A second US rescue followed in 1944, ushering in a bipolar world that, combined with anticolonial insurrections and military defeats in Indochina and Algeria, shrank France’s global presence. In the 1950s and 1960s, the construction of a unified Europe on a French model and new technologies such as the Concorde jet would reassure the French that they still mattered in the world. But the economic crisis that began in the 1970s deepened doubts about something more elemental: the French welfare state’s ability to ensure social justice in an increasingly neocapitalist world. As growth slowed, high unemployment became an enduring reality, especially for women, young people, and immigrants. The labor market turned increasingly toward part-time, temporary, and unskilled employment with scant prospects for job security or social benefits. Growing segments of the population felt less secure in their positions in society. A 2006 poll found that half of the population feared losing their home one day. Sociologist Robert Castel gave a name to these feelings of uncertainty, fear, and isolation: “disaffiliation.”

Should we be surprised, then, that so much of the recent public debate in France has revolved around national history, as if the past could renew collective filiation? To fully understand this latest nation-talk, we should return to the early nineteenth-century view of national history as “a kind of common property … for all the inhabitants of the same country” (Romantic historian Augustin Thierry). We should examine the national school curriculum that, from the 1880s on, turned the likes of Gaul chieftain Vercingetorix into heroic actors of the national narrative. We should also listen to the critical voices that, in the second half of the twentieth century, requested a less parochial approach to national history — with mixed success if one considers the curriculum’s longtime neglect of immigration, its renewed emphasis on assimilation in the 1970s, and its difficulties reckoning with French colonial violence. When it comes to slavery and its demise in the French Caribbean, pupils have learned more about French abolitionists such as Victor Schœlcher than about their country’s brutality or the ways in which colonized subjects fought for their own emancipation.

To understand the current nation-talk, we must finally recall that, since the 1980s, the French right, the extreme right National Front, and some die-hard républicains have promulgated a closed notion of national identity. The presidency of Nicolas Sarkozy (2007–2012) looms large, with its embrace of a history rooted in an immemorial past, a history in which the Gauls constitute the sole ancestors of all French citizens, regardless of their geographic origins. The title of Sarkozy’s new Ministry of Immigration, Integration, National Identity, and Co-Development left little to the imagination. During the past decade, the aftereffects of the Great Recession, the arrival of migrants and refugees, the circulation of workers across the EU, and the radicalization of certain Muslim Europeans have galvanized nostalgia for an eternal, exceptional spirit — true France.

Convinced that neglect of this spirit is accelerating their nation’s undoing, some French ideologues insist that the only way to reconcile the French with one another is to defend their vision of the country’s history. Right-wing and extreme-right candidates sang the same tune during the 2017 French presidential campaign. “To be French is to feel at home in an epic in which everything flows together,” declared Sarkozy’s former prime minister François Fillon. “With our homeland desperately thirsting for meaning, with the threat of internal division looming, shouldn’t our schools impart the story of the nation?” And with the British choosing Brexit in June 2016, Trump’s victory months later, and Marine Le Pen leading many polls in 2017, France’s own political future seemed as uncertain, potentially, as those of its allies.

The editorial collective behind France in the World deemed it imperative to tell a story about the nation that refuted this panicked recourse to ethnic categories, this rush to enclose, separate, contain, and delimit what properly belongs within French history. Following the January 2015 attacks, Patrick Boucheron and writer Mathieu Riboulet spelled out the specific interventions historians could make in the current climate: puncture slogans and symbols (such as the “Marseillaise”), define the principles worth defending, stimulate understanding by describing people and historical situations with precision and beauty, and write an open, generous, inclusive history.

The book’s focus on the nation thus owed much to tactical considerations and political conviction. On the one hand, it enabled historians (and certain segments of the left) to regain their public voice, to intervene in a debate that had sidelined them. On the other hand, it tapped into and bolstered history’s ability to weaken habits of obedience and belonging, inviting readers to imagine alternative horizons. In dialogue with Nietzsche and Michel Foucault, Boucheron has insisted that the historian’s primary responsibility is to institute discontinuity. “Even in the historical realm, to know is not to ‘recover’ and especially not to ‘find oneself.’ History is ‘effective’ to the extent that it introduces discontinuity within our very being.”

Accordingly, France in the World disrupts the seemingly natural, exhaustive order of chronology. By inviting us to slow down as we read, to take a step sideways or even a detour in order to see something else, it draws us into the accidental and sometimes imperceptible movement of historical time. By unmooring political myths that have taken shape over the centuries, most notably in the works of nineteenth-century historians, this critical book also opens dialogues between historical eras. Contrary to the national narrative, the 843 Treaty of Verdun did not distinguish what would become Romance-speaking “France” from German-speaking lands; this is a “projection onto the past” of modern nationalism. Countless other myths are laid bare in France in the World: among them, Marseille founded by Greeks who civilized “savages” in 600 BCE; Charles Martel stopping the “Arabs” at the Battle of Poitiers in 732; and the Gaullist Resistance to Hitler emerging in London alone (rather than in France’s African colonies). All have been fashioned at specific historical moments, following procedures that require elucidation — demythification.

Discontinuity also shapes France in the World’s relationship to space. This decentered history moves between the city and the region, the nation and the continent, or rather the various nations and continents of our planet. The familiar expanses of mainland France are visible in the essays: mountains and rivers, coastlines and vineyards, Paris and Versailles, Flanders and the Riviera. But France as it is rendered here remains open to the world, its borders permeable. The contributors connect the country and its residents to Carthage and Siam, Scandinavia and the Middle East, Algiers and New Caledonia, Rome and New York City.

In this regard, France in the World recognizes, along with a growing number of historians, that nation-states are embedded within networks, connections, interdependencies that range far and wide. Global history has come into its own these past two decades, in a world that, given the fall of the Berlin Wall, shared environmental challenges, and the acceleration of technological innovation and capitalist exchanges, is increasingly interrelated. Scholars have examined the circulations and power dynamics that have shaped the Atlantic world across several continents. Drawing from postcolonial criticism, they have rejected the assumption that European ideas and processes are necessarily embraced or replicated elsewhere. Seeking out the visible or hidden threads that connect peoples and regions across national borders, they have followed flows of people and goods, of cultural horizons and political designs.

France in the World hence displays affinities with transnational or “connected” history. We detect in this volume the same attention to minute yet meaningful interactions and relationships; the same curiosity for both non-Western and Western perspectives; and the same comingling of temporalities and geographical scales. There is the same desire to understand, not just abstract economic or social forces, but the ways that individuals of various social stations have understood, experienced, and shaped their “lived world.”

In this domain as in others, the editors refrain from imposing a single framework, thereby freeing the contributors to write this history of France in the world as they see fit. Some essays explore French relationships to globalization, from technological embrace (the Suez Canal in 1869) to economic doubts (the 1992 referendum on European unification). Others juxtapose developments taking place in different lands, or else follow the circulation in and out of “France” of legal codes, consumer products, texts (the Quran), political programs (feminism), and architectural styles. Yet others scrutinize French notions of universalism and national genius. France’s imperial and colonial presence surfaces in numerous essays. Embracing an increasingly prevalent view of the country as a longtime empire-state, France in the World pays as much attention to the colonizers’ governance and their violence as it does to the culture and politics of formerly enslaved people, subjects, and independence fighters.

This book stands out, moreover, because, despite recent advances, France has relatively few journals, academic chairs, programs, and research centers devoted to global history. Is it because of French distrust of intellectual frameworks that seem to originate in the English-speaking world and might thus represent a form of US soft power, spreading neoliberalism? Is it because new historical labels such as “world” or “global” history have seemed superfluous in a country where eminent French scholars have long looked beyond national borders (Fernand Braudel, Pierre Chaunu) while colonized or postcolonial writers penned penetrating analyses of racial politics (Aimé Césaire, Leïla Sebbar, Abdelmalek Sayad)? Patrick Boucheron has suggested that the complex ideological legacy of Braudel’s “grammar of civilizations,” which gives little consideration to change or contacts between world cultures, prevented French scholars from fully embracing global history. Institutional factors may have come into play as well. Small, selective centers of research and higher learning such as the National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) and the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales have the means and flexibility to put disciplines into conversation with one another while training faculty in new methodologies and languages. The situation is more complicated, however, in most public universities, with their threadbare budgets, operating deficits, heavy bureaucracy, overflowing classrooms, and high faculty workloads.

We must, finally, consider the impact of a French republican ideology that defines citizenship in purely political terms, entertaining the legal fiction that citizens and the nation are abstractions, divorced from race, ethnicity, or sexuality. Since the French Revolution, one has in theory been French before being Protestant, Jewish, an Italian immigrant, homosexual, a black woman. The Vichy regime’s racial and ethnic record-keeping exacerbated the taboo surrounding the political uses of such categories. While subnational identities are not completely suppressed in France today, their public expression remains problematic. As the political philosopher Elsa Dorlin recently explained, French scholars still must justify their attention to race or ethnicity as contributing factors behind social inequality. They must make it clear that they are not contesting their republic’s understanding of citizenship and color blindness. How then, asks legal scholar Mathilde Cohen, “can one study and make sense of what appears to be largely unspoken and unspeakable?”

Debates over the pertinence and even the legality of racial or ethnic categories in law, official statistics, scholarship, and public discourse are far from exhausted in the French Republic. And yet, there are signs of change within nation-talk. A growing number of scholars reject the notion that racial or ethnic inequalities result from socioeconomic domination alone; they also insist that shunning notions like race stymies efforts to contain racism. Theatrical troupes like We Will Never Give Up Hope (NAJE, in the Parisian suburb of Antony) dramatize pressing questions like migration in order to generate “social transformation.” The National Museum on the History of Immigration (founded in 2007) tells visitors that “adaptation, borrowings, and mixings” are central to France’s national heritage. In 2018, the television channel Arte aired Le rêve français (The French Dream), a miniseries about residents of Guadeloupe and Réunion Island who were brought to metropolitan France from the 1960s on and pushed toward low-wage jobs. Seldom has this story been told. “This is a movie about national identity,” explained one of its producers. “We have sought to free up language in order to enable people to recapture their history.”

France in the World thus represents one of many forces that, within French civil society, seek to free up language (about the nation and the world, the present and the past) in order to enable people to recapture meaningful yet sometimes silenced histories. More resolutely than others, perhaps, this collection marries critical clarity with hope. Annie Jourdan sets the tone in her essay on 1789, speaking of an “internal conflict … between the resolve to emancipate people across Europe and the temptation to turn inward.” Read the essays on 1790, 1927, or 1974 to watch French institutional and cultural forces stymie hospitality. At the same time, recall that the Hungarian-born Saint Martin (397), the foreign corsairs and privateers of Dunkirk (1662), the Kanaks who fought either for or against France in 1917, and many other “foreigners” all shaped a national space in which, as Alain de Libera puts it in his essay on the medieval University of Paris, “different origins and identities gathered, clashed, and fused” (1215). One can be French and also Spanish or Tunisian. One can espouse several identities at once. This has happened before; new forms of diversity do not threaten France; the country is not waging an internal battle against new barbarians. There are other stories worth telling besides national decline. In France today, this needs to be said.

Others concurred at the time of publication: The newsweekly L’Obs praised France in the World as an “antidote to all national pseudo-identities”; the daily Libération applauded it for “refuting the idea of a rigid, solemn, teleological history that leads to nationalism alone”; the magazine Témoignage chrétien commended it for showing that French history “is before all the history of the French in their plurality and mobility.” Emmanuel Macron confessed to reading the collection with pleasure and rejected, during his presidential campaign, the notion of a fixed national identity: “The French national project has never been sealed off from the world,” he declared.

It must be said, however, that Macron the candidate also paid homage to the mythic Joan of Arc and advocated the teaching of “a national narrative,” and also that, in the midst of the Yellow Vest protests in the winter of 2018–2019, Macron the president called for a national agreement on France’s “deep-seated identity,” a question he linked to immigration. Beyond such rhetorical contradictions, the more reactionary champions of this national narrative have denounced France in the World in pointed language. In its narrowest terms, the polemics revolved around what the book leaves out or minimizes, from the building of cathedrals to radical French revolutionaries. The editors’ decision to begin with prehistoric times rather than mythical moments (such as the baptism of Clovis I) did not go unnoticed, either. More broadly, these critics decried an “intellectual act of war” that sought to “assassinate France” by denying its true genius.

How could one include Frantz Fanon, the Martinique revolutionary and philosopher, and Zinédine Zidane, the soccer player whose parents were born in Algeria, but not writer Germaine de Staël or composer Claude Debussy? Every historical work rests on editorial decisions, and the ones that lay behind France in the World are naturally open to discussion, but, for these critics, these choices represented a crime of lèse-nation. “How can one go so far in the deconstruction of French identity?” asked essayist Alain Finkielkraut, the forlorn defender of the French Republic, mourning “a wounded [national] identity.”

Should we assume that “anything that comes from abroad is good?” asked the nationalist provocateur Éric Zemmour, whose anguished ruminations on national decline yielded a best seller in 2014, Le suicide français. Historian Patrice Gueniffey — author most recently of Napoléon et de Gaulle: Deux héros français (2017) —warned that the editors’ perceived disregard for the country’s heritage was bound to feed what he called “disaffiliation.” The term brings to mind Robert Castel even if, in Gueniffey’s prose, recent transformations of labor matter less than, once again, the disintegration of an idealized nation. The threat posed by France in the World justified the most furious indictments (Gueniffey accused the book’s editors of being “heirs of Vichy France”).

While this language was surprisingly violent, one might have expected this kind of objection from such quarters. After all, the editors were convinced from the start that intellectual energy alone could counter retrograde visions of the nation. To this end, they invited contributors from multiple generations and disciplines. There is a preponderance of younger scholars, and essays by not only historians, but also political scientists, literary scholars, art historians, archaeologists, journalists, economists, and half a dozen archivists. France in the World opens a conversation among scholars who do not always speak to one another within France’s specialized and hierarchical academic circles.

In this respect as in others, the French situation can prove befuddling to outsiders. The centralization of higher education, with seventeen universities and hundreds of thousands of students in or around Paris, creates a concentration of historians without parallel in, say, the US, where scholars are located in numerous centers of comparable importance (Washington, DC, to be sure, but also Boston, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, the San Francisco Bay Area, and others). Universities in the French provinces and overseas territories such as Martinique or Guadeloupe often lack the intellectual density and institutional resources of their Parisian counterparts (even if many of the latter have equally tight budgets). Moreover, women face considerable obstacles in the French academic world. While they make up roughly half of the junior faculty in the humanities, their number drops precipitously once one moves up the ladder. The same is of course true in the US, but calls for equity and diversity are much more vigorous on American shores, where attempts to rectify such inequalities are connected to longstanding political movements, academic departments, and intellectual currents (gender studies, critical race theory, intersectionality) that, like affirmative action and efforts to limit implicit bias, have acquired on most campuses a legitimacy that remains fragile in France.

These factors help explain why just under a third of the contributors are women; why the majority were trained and work in France and especially in Paris; and why none are based in Martinique or Guadeloupe or former French colonies such as Algeria. While the US is no paragon, an equivalent American book would no doubt have conceptualized diversity in different ways. We can presume that its initial premise would have been that different scholars write different global histories, that they ask different questions and notice different things depending on their physical, institutional, and cultural locations.

It must be said, however, that some things are changing in France in this regard as well. Regional centers of academic excellence are gaining stature. Prestigious journals such as Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales (whose editors are well represented among the contributors to France in the World) have recently reexamined their editorial procedures to include more women in their editorial committee and within the ranks of the scholars they publish. Furthermore, in the fall of 2018 more than five hundred female historians signed a petition protesting “masculine domination” in their profession. The signatories included more than fifteen contributors to France in the World. Might we cautiously speculate that, alongside other factors (including in this case the #MeToo movement), this editorial venture, this forceful public intervention energized certain historians? The book’s aftereffects may well play out in unpredictable ways in the years to come.

As this translation goes to press, wistful accounts of national history keep landing in French bookstores. In 2018, the right-wing writer Jean-Christian Petitfils penned his own history of France on the grounds that his divided country needs a unifying narrative to “once again instill pride in national cohesion.” Predictably, Petitfils subtitled his book “The True National Narrative” (Le vrai roman national). No surprise here. But surely there are other ways of exploring the past (or rather our multiple pasts), other reasons why in France as elsewhere we need historians. Beyond what it teaches us about the French past and present, France in the World raises fundamental questions about the place of history and the kind of history we want in our public space. It also intervenes in one of the central political battles now being waged on several continents, when closed, populist visions of national identity target looser, pluralistic understandings of cultural identification.

It is impossible to tell which camp will prevail, even in the US. In an age of disquiet in the face of global mobility, an age when national myths of continuity and rootedness retain such a strong hold, nothing guarantees that open-ended histories of diversity and flux will win the day, even if they show how some people and institutions draw lines that define and separate, and how some people cross these very lines. At the same time, there are costs to refusing to counter rigid national narratives with freer, more precise alternatives that are grounded in research. Let us then believe, along with the contributors to this bracing collection, that historians have something distinctive to tell us about the world we inhabit.

Let us expect historians to play a vocal role in our public debates — sometimes to clarify and sometimes to make our world more complicated, more open to ambiguity, more discontinuous.

And let us pay close attention to the literary experiments of historians who are also writers, historians who believe, with audacity and necessity and — yes — urgency, that knowledge and language have the power to liberate us.

A note on the translation: This edition is both slightly slimmer and slightly heftier than the original. We have translated 90 percent of the French-language essays, asked the editors to flesh out the twelve section introductions, and invited the contributors to update some of the references that follow each essay, and where pertinent add English-language sources. Otherwise, the book is the same.

OVERTURE

Patrick Boucheron

“It would take a history of the world to explain France.”

— Jules Michelet, Introduction to World History (1831)

An introduction to the history of France?

Most readers, I know, would rather do without. You’ll skip it. You’ll want to embark directly on this fresh ocean of history, full of events, hopes, and memories; you’ll expect plain sailing as well as sudden squalls of things remembered and associations of ideas, buffeting you from one shore to the next. Who needs an introduction to that? Who needs ponderous preliminaries? The introduction to French history can prove wearisome, if not intimidating, with its accumulation of centuries, its solemn and eminent scholars, and its controversies. Historians are after all expected to express, practically on their own, the anxieties of their era.

The very thought of an introduction induces lethargy. I know all this, and will thus confine myself to explaining as briefly as possible the astonishing speed with which this book brought a number of us together, and why this collective endeavor sparked so great a sense of urgency in us all.

So this is more an overture (whatever is morally or politically meant by this) than an introduction; and even then, it bears comparison less to a musical composition’s majestic prelude than to a camera’s aperture (ouverture), which a photographer adjusts to change the depth of field. In sum, the authors of this volume shared a common ambition to write a history of France that would reconcile the storyteller’s art with absolute critical rigor. This new history would be open and accessible to the widest possible readership, while remaining within the familiar framework of dates.

The result is political inasmuch as it seeks to mobilize a pluralist concept of history against the general shrinkage of national identity that is such a central component of the public debate in France today. As a matter of principle, the history we set forth refuses to surrender the “History of France” to knee-jerk reactionaries or to concede them any narrative monopoly. By approaching the subject from the open sea (so to speak), by catching the élan of a historiography driven by strong, fresh winds, it seeks to recover the diversity of France. This is why this venture has taken the form of a collective editorial project. France in the World gives voice to a group of historians, male and female, working in concert toward a history that is both committed (engagée) and scholarly. This book is a joyous polyphony, not by happenstance (how could anybody today presume to write a full history of France single-handed?), but by choice.

We have traveled light. Embarking on this adventure, the 113 authors who put their trust in the initial project agreed to shed the theoretical apparatus that typically accompanies academic writing. They would no longer accept the increasingly prevalent apportioning of roles that places historians at a disadvantage: meaning, to journalists and essayists, the easy narrative option of a story invidiously discounting evidence, and to historians, the awkward exercise of aligning a good story with the cold requirements of a rigorous method. “It’s more complicated than that” is the constant objection to straightforward history. Certainly — but hiding behind complexity cannot be the last resort of historians, unless they want to be professional purveyors of disenchantment. Responsible critical work is not systematically dry and dreary; in fact, it can be absolutely enthralling. Using the investigative approach, a historian can show how the past is forever made and unmade by the changing frames of history. History does not speak for itself, in the clear light of the evidence; we can only view it through the prism of our knowledge.

Consequently, our general guidelines have been to write history without footnotes and without compunction — a history that is living because it is constantly renewed by research, a history for those with whom we enjoy sharing it — in the hope that some of the pleasure of the sharing would relieve some of the desolation of our present times. Writing without notes and without compunction does not mean that we compromised the requirements of our profession, for at the end of each chapter the author has listed the key scholarly references on which it was based.

Every contributor was given complete freedom to construct an essay coinciding with a given date in the history of France — whether that date was already part of the chronological frieze of the national legend or had to be imported from another compartment of the world’s memory. Focusing on dates was clearly the most effective way of unraveling the fictitious continuities of the traditional narrative: for dates make it possible to point out connections, or readjust them, or even resolve apparent incongruities. Indeed it is this dual action — displacing and unmooring feelings of belonging while welcoming the strange familiarity of what is distant — that the chronicle, with its cheerful sequence of events, tends to put to the test.

We didn’t have to systematically seek out counterintuitive or untraditional positions; the canonical dates in French history are present in this book, although they are sometimes a bit off-kilter, shaken by the will to see in them the local expression of wider movements. From the ashes of a pseudo-nostalgic tale we were taught in school, there might arise the phoenix of a broader, revivified, and more diverse history.

Our contributors had something else to go on: a line by the historian Jules Michelet, chosen as our book’s epigraph: “It would take a history of the world to explain France.” These enigmatic words convey a certain longing — and a certain unease. In truth, longing and unease have turned out to be among the driving forces behind our project, forcing each of us to write with complete freedom.

When he wrote the line above in 1831, Michelet was thirty-two years old. As a lecturer at the École normale, he was teaching people younger than himself a history that had much in common with philosophy: in fact, it was, strictly speaking, a philosophy of history. The 1830 Revolution, which toppled the Bourbon dynasty for good, had brought the hope of political freedom. This hope awakened the people of France, a humanity within which, unlike most historians of his time, Michelet detected sufficient strength to resist the fatal destiny of what contemporaries called race. A true son of the Revolution, he championed an open, energetic, vital history that could not be shackled by theories of immutable origin, identity, or destiny. “That which is the least simple, the least natural, and the most artificial, meaning the least predestined, most human, and freest entity in the world, is Europe; and the most European country of all is the land of my birth, which is France.” Thus the arrow of time flew onward, and this is why, for Michelet, an Introduction to World History could only be an introduction to his history of France.

But we should be wary of facile parallels. Although Michelet appeared out of place in his own time, he is by no means squarely in line with our own. We can no longer agree with him that France is “the glorious fatherland [that] will henceforth steer the ship of humanity.” Today, Michelet’s patriotism is fatally compromised by a history — for which he was of course not responsible — in which France’s “civilizing mission” excused blatant colonial aggression. Was this a terminal surrender of principles? Many since Michelet’s time have believed that the reinvention of a universalist “constitutional patriotism” open to the diversity of the world could provide the best defense against a dangerously narrow-minded nationalism and its constricted understanding of national identity. But this is not our subject here. It is enough to acknowledge the extent to which Michelet’s dream of a France that one can only explain in global terms has been a source of comfort and inspiration.

Lecturing at the Collège de France from 1943 to 1944, the brilliant historian Lucien Febvre reflected at length on Michelet’s little-known text. He did so to cast light on the much more celebrated Tableau de la France that opens the second volume of Michelet’s History of France (1834). As far as Febvre was concerned, Michelet’s idea was to loosen this geographical entity, to undo “the idea of a necessary, predestined, preordained France, ready made by Frenchmen, by describing as ‘France’ all the formations and human groupings that existed before Gaul on what is today our territory” (lecture 25, 1 March 1944). Living in Nazi-occupied Paris, receiving from his disciple Fernand Braudel, then a prisoner in Mainz, chapter after chapter of the latter’s The Mediterranean, Febvre evoked the historical moments when, as in the time of Joan of Arc, France “came close to vanishing.” He also spoke of historians who, like Michelet, had “erased the French race from our history.”

Once and for all? Let’s not be naive. After the war, Lucien Febvre reentered the fray against what he had earlier called the “prejudice of predestination,” the idea that a country’s history can only be guided by a national destiny (A Geographical Introduction to History, 1949). Answering a 1950 appeal by UNESCO, which wanted to make history an auxiliary science in the search for universal peace, Febvre and historian François Crouzet developed a project for a textbook describing the development of French civilization as a fraternal growth of mixed cultures (this book was finally published in 2012 as Nous sommes des sang-mêlés [We Are of Mixed Blood]). What Febvre called civilization was the capacity to overflow: “French civilization, to speak only of that, has always gone beyond the political borders of France and the French state. Knowledge of this fact does not belittle France; on the contrary it makes the country greater. It is a source of hope for her future.”

Whence comes the strange notion that opening to the world would diminish France? By what paradox have we come to view the history of our country as an endless struggle to protect its sovereignty from outside influences that somehow denature and hence endanger its very essence? In the last thirty years, the travails of French society confronted by the challenges of globalization have focused public debate on the question of national identity. In terms of historical writing, the tipping point came somewhere between the publication of the first volume of Pierre Nora’s Les lieux de mémoire (Realms of Memory) in 1984 and that of Fernand Braudel’s The Identity of France in 1986. The demand for a specific French identity, which found early supporters among the left (then in power), led to the defense of a French culture defined by a right to be different. Thereafter it fed a critique of cultural diversity wherein hostility to the supposedly destructive effects of immigration became more and more clearly defined.

On October 16, 1985, Braudel presented his lycée pupils in Toulon with a fascinating analysis of a siege of the city that took place in 1707. This world-history story was designed to show not only that “France’s second name was diversity,” but also that France’s political and territorial unity had been forged slowly, “through connections made more recently by the railways” rather than at the time of Joan of Arc, as Braudel’s students might still have been taught. Braudel’s death a month later ended the writing of what he had begun to call his “History of France,” which he predicted would be “misunderstood.” And so it was: his unfinished Identity of France, published posthumously, was read as the political testament of a historian who dealt with long-term historical structures (the longue durée). In reality, the book was no more than a provisional time halt for history on the move. We cannot relaunch this history without drawing — as Braudel did — on Lucien Febvre, who himself explained Michelet’s Tableau de la France through his scintillating Introduction to World History.

Many young French researchers are already moving in this direction. Some draw inspiration from Thomas Bender’s striking book A Nation among Nations: America’s Place in World History (2006), which proposes a global history of the US as no more than “a nation among others.” To approach the American Civil War as just one among numerous independence struggles which, in Europe and in the wider world, articulated the issue of nationality and the ideal of liberty, inflicted a narcissistic wound on a country that sees its national story as something unique and exceptional. Other historiographical experiments in the same vein have been attempted; for example, a transnational history of Germany, and an account of the Italian Renaissance in terms of the Mediterranean. But while historians of the French Revolution and of France’s colonial empire have begun to adopt a global approach, a global history of France herself is yet to come. France in the World certainly isn’t that: it merely formulates the premise — perhaps the promise — of such an approach in future.

What do we mean by the global history of France?

First of all, a history of France that forsakes neither the great places nor the great figures of our history. It is not so much a case of embracing another history entirely as of writing the same history in a different way. Instead of embracing knee-jerk counterhistories or losing ourselves in the labyrinths of deconstruction, we have tried to come to grips with the questions that the traditional history of an immutable France falsely claims to resolve. We hence offer a global history of France, not a history of global France: we have no intention of following the long-term expansion of a globalized France in order to exalt the glorious rise of a nation devoted to universalism. Nor do we wish to sing the praises of self-satisfied ethnic diversity and migratory cross-pollination. Believe us when we say that we are not trying to celebrate or denounce anything. The fact that history has for so long been a critical science and not an art of acclamation or detestation is an issue that we hoped had long been settled. And yet, it faces such vehement enemies nowadays that it is perhaps a good idea to once again say something in its defense.

To explain France by the world, to write the history of a France that is explainable with the world, that engages with the world: such a venture is bound to undermine the false idea that France and the world are somehow symmetrical. France does not exist separately from the rest of the world; likewise, the world’s consistency in France changes over time. The world of Roman Gaul and the world of the Franks looked to the Mediterranean. The kingdom of Saint Louis looked to Eurasia. But at different points in the long history of globalization, of the changing relationships between what took the name of “France” and that which was understood as “the world,” there kept arising other social configurations, multiple affiliations, unexpected bifurcations, and geographical shifts. In short, history was on the move. Rather than calling our own book a global history, we might have defined it as a “long” history of France, starting eons before the brief period during which the country has come into its own as a political entity, as a nation. The old notion of “general history” may also be applicable inasmuch as our approach aspires to nothing more than the honest analysis of a given space in all its geographical breadth and historical depth.

Such then is our project. It is neither linear nor aimed at a particular target, and it has no beginning, no end. Our earliest dates explore the most shadowy periods of human occupation of the territory today identified as French, precisely to circumvent the question of national origins. The dates draw closer together when the connections between them grow more numerous (in the years 1450–1550, for example) or when France attempted (as in the seventeenth century, with the growing power of its absolute monarchy) to fan out across the world or even to contain the world by embracing a universalistic outlook within which French constituted our planet’s language of revolutionary hope. At other times, this history opens onto missed opportunities, withdrawals, and retractions — for instance, in the wake of the globalization à la française that begins in the late nineteenth century

In all honesty, none of this adds up to a coherent history, at least not yet. If the 131 dates we have chosen in this edition of the book do not exactly form an articulated chronology, it is because they cannot on their own support the exhaustive recital of a global history of France. By drawing attention to certain events, they naturally add weight to political and cultural readings, neglecting longer-term economic and environmental changes. We have knowingly left open yawning gaps that readers will certainly notice: while some were perhaps unavoidable, for others we will be held responsible, and rightly so. Let me add that the sequences or sections these dates define are not supposed to represent definite periods: they are only there to guide the reader, who may also wish to escape the beaten path by way of the index, the list of pertinent dates that close each chapter, or the journeys across time that, at the end of this book, suggest thematic routes and unexpected juxtapositions.

Finally we have to confess that, more than anything, it was the principle of pleasure that guided us as we put this book together. Not that we ever meant to write a happy history: France in the World is neither lighter nor darker than any other book (though its gravity is hardly despondent). Still, there is something to be said today on behalf of the joyous energy of a collective intelligence. We hope that a little of the delight we experienced while perpetually surprising ourselves, while joining forces in this collective enterprise, while trusting one another and working hard to avoid disappointing one another, will prove contagious. To those who ask why this history of France is a global one, we simply respond: “Because this makes it so much more interesting!”