Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

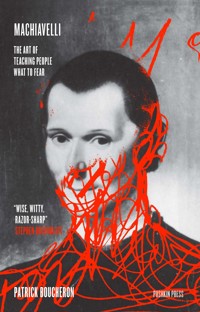

"Wise, witty, razor-sharp" Stephen Greenblatt, author of The Swerve: How the Renaissance Began Interested in Machiavelli?That may be a bad sign. We always turn to Machiavelli at crisis points in history - he is the philosopher for dark times. But what do we really know about this man? Is there more to his work than that perennial term for political evil, Machiavellianism? In this concise, elegant book, Patrick Boucheron undoes many assumptions about this most complex of figures. By honing in on Machiavelli's role in the political life of his own time, Boucheron shows how his thought remains essential to understanding not only how authoritarianism works, but also how it can be fought.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 109

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

“A historian makes a case for Machiavelli as misunderstood and villainized figure with political insights that can be applied to modern times”

NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

“To reframe our understanding of Machiavelli, Mr. Boucheron asks, who was he writing for?… If The Prince was meant to help ordinary people understand what their leaders were up to, then it is not a handbook for the power-crazed but a means of stopping them”

WALL STREET JOURNAL

“A penetrating portrait of a complex political thinker”

KIRKUS REVIEWS

“Machiavelli provide[s] a distinct perspective on the influential philosopher… Readers looking to learn more about the thinker, as well as those seeking an introduction, will find this creative work appealing”

LIBRARY JOURNAL

“Patrick Boucheron gives us a trenchant analysis of Machiavelli’s complex and slippery ideas. Even more useful and illuminating, with Machiavelli as his guide, he probes our own political life and times. In an age of shrill and often senseless debate, it’s a pleasure to read such a subtle and gently provoking thinker”

ROSS KING, AUTHOR OFMACHIAVELLI: PHILOSOPHER OF POWER

“A more nuanced and comprehensive look at this brilliant but tortured genius… highly recommended”

NEW YORK JOURNAL OF BOOKS

“Patrick Boucheron’s little book is by far the best inducement to Machiavelli that I know of, to the point that I will have students read Boucheron’s Machiavelli rather than Machiavelli’s Prince in my surveys. I am sure that they will then get to the Prince, and not for class, but for themselves”

FRANCESCO ERSPAMER, PROFESSOR OF ROMANCE LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES, HARVARD UNIVERSITY

MACHIAVELLI

THE ART OF TEACHING PEOPLE WHAT TO FEAR

PATRICK BOUCHERON

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH BY

WILLARD WOOD

PUSHKIN PRESS

CONTENTS

MACHIAVELLI

FOREWORD

ARE YOU GENUINELY INTERESTED IN MACHIAVELLI? Are you sufficiently interested in him, now, in the present day, that you’re eager to read this book? Forgive me, then, for informing you that this doesn’t count as good news. Because ever since Niccolò Machiavelli, one-time Secretary of the Florentine Republic, died in 1527, the body of work he left has continued to haunt posterity, like some phantom incessantly obsessing the living. He returns periodically, like a violent thunderstorm: during the years of the Wars of Religion, the revolutions of the eighteenth century, or the tragedies of the twentieth century. Every time that the specter of tyranny strides the landscape. At times like these, we remember that the author of The Prince was less interested in counseling the powerful than he was in awakening the consciences of the decent, teaching the people to look impending catastrophes right in the face, with a realistic eye. What, then, should we really fear? Far from any exercise in virtuous indignation or appeal to enchanting principles, the art of politics, as Machiavelli sees it, is entirely bound up 2with this important lesson in realism. It is fully comprised of this call to the order of reality, which is also an appeal to the requirements of description and verification: if we can learn to name things as they happen, then we can begin to take arms against them. And it’s every bit as much about poetry as it is about politics. Machiavelli walks again, then — and when we, in the present day, read what he has to say about the tyrants of his time, we cannot help but think about the tyrants of ours. Must we call them by their names? I don’t think so. After reading Machiavelli, after accepting him as a brother in arms, a comrade in dire straits, I’ve still always resisted the temptation to state explicitly the echoes he stirs in my mind. Because the fact that Machiavelli remains unfailingly relevant has much to do with the way that his writings are like a computer program that automatically downloads and installs its own updates. Read, then, and you will see. Ever since his own long-ago times, he has always been a citizen of our own modern times. He speaks to you, reader, about yourself, and he speaks to you about the present day.

—translated into English by Antony Shugaar

Giovanni Stradano, Mercato Vecchio, Florence

YOUTH

Sandro Botticelli, Spring (detail)

ONE

THE SEASONS

MACHIAVELLI IS FIRST AND FOREMOST a man of action, always doing battle, a man for whom describing the world and giving a clear-eyed account of it is to make progress toward transforming it. “Anyone who reads my work,” he said in 1513 about The Prince, “will clearly see that in the fifteen years during which I applied myself to the study of government, I was neither nodding off nor wasting time.”

His work has been read since his death in 1527 and is still read today, despite his critics and detractors. It invariably rouses us from our torpor. And why not, since Machiavelli is as implacable as the summer sun. It is that celestial orb that gives his words their bite and casts on his subjects such a naked light that the bones show. Nietzsche has said it better than anyone, in Beyond Good and Evil: “He lets us breathe the fine, dry air of Florence in his Prince and cannot keep from presenting the most serious business in a wild allegrissimo, perhaps not without an artist’s malicious feeling for the contradiction he is attempting: the thoughts long, heavy, harsh, dangerous, 8set to a galloping tempo of the finest, most mischievous mood.”

But if it’s all a matter of rhythm, how could he not have noticed that the qualita dei tempi, as he called it, the quality of the times, had reached the autumn of certainty? Italy had been at war since 1494. Proud of its city-states, sure of its cultural preeminence, Italy was nonetheless experiencing unprecedented violence at the hands of the continent’s large and predatory monarchical states. This is known as the Italian Wars, a period of great disenchantment. And because the Italian Peninsula had been the laboratory of modern politics for so many centuries, the place where the common future was invented, the approaching war was unmistakably the herald of what would come to be called Europe.

The shadows lengthen, winter steals in, numbing men’s souls. Machiavelli knew all this well: the words that freeze behind closed lips, the inability to express what we are becoming. He knew the slow and inexorable slide of a political language into obsolescence. The language he had learned with such delight from books no longer served to accurately render “the actual truth of the matter.” When the recent past was no longer any help, why should he not turn toward those he called his “dear Romans,” plunge into ancient texts as if into a large, refreshing bath, and give the name “antiquity” to this invigorating way of recasting the future?

Is that what we call the Renaissance? Why not, if we’re willing to open our eyes to this spring, whose colors 9are vapid and innocent only to those who cannot see the brutal ferocity of a Botticelli canvas. Machiavelli is the master of disillusioning. That’s why, all through history, he’s been a trusted ally in evil times. For my part, I don’t think of myself as working on Machiavelli. But with him, yes, as a brother in arms — with the caveat that because he was always a scout, always in the forefront, we must read him not in the present but in the future tense.

All of which is to say something perfectly straightforward: interest in Machiavelli always revives in the course of history when the storm clouds are gathering, because he’s the man to philosophize in heavy weather. If we’re reading him today, it means we should be worried. He’s back: wake up. 10

Santi di Tito, Portrait of Niccolò Machiavelli

TWO

MACHIAVELLIANISM

ORWELLIAN, KAFKAESQUE, SADISTIC. Machiavellian. Having one’s name identify a collective anxiety is a dubious honor. In his dictionary of the French language, Émile Littré gives the following definition of “Machiavelli”: “Florentine author of the sixteenth century who theorized the practice of violence and tyranny used by the petty tyrants of Italy.” A figurative sense is immediately tacked on: “Any statesman lacking principles.” Example: “The Machiavellis who rule our fates.”

By saddling Machiavelli’s name with a figurative meaning, Littré did a strange thing, but history itself did no less. Machiavellianism is what stands between us and Machiavelli. It gives manifest shape to what is evil in politics, it is the hideous face of all that one would like to disavow, but it’s hard to close one’s eyes to it. It is also a mask behind which the man, Niccolò Machiavelli, who was born in Florence in 1469 and died there in 1527, disappears.

In fact Machiavellianism is not a doctrine Machiavelli formulated, but one that his more malicious adversaries 12have imputed to him. It’s an invention of anti-Machiavellianism. Within fifty years of Machiavelli’s death, The Prince had taken its place on the Catholic Church’s Index of Forbidden Books as a work of the devil, and many political treatises took the title Anti-Machiavel. The genre’s inventor, a French lawyer and Protestant theologian called Innocent Gentillet, would seem predestined by his name to battle the uglier aspects of the world.

A few years later, it was a brilliant Jesuit, an ardent Counter-Reformationist, who took up the cudgels against Machiavelli. His name was Giovanni Botero, and he invented the concept of “reason of state,” a concept immediately ascribed to Machiavelli, since it suggests that the state knows no law or requirement other than self-preservation.

From that point on, Machiavellianism ran like an underground river below the foundations of European political theory, silently eating away at them and occasionally resurfacing into view. Machiavelli persists, wearing a mask: we recognize him behind one or another of his borrowed names; we deduce his ideas from those that are given supposedly in opposition.

Gustave Flaubert, writing around the same time as Émile Littré, produced a Dictionary of Conventional Wisdom that defines both “Machiavellianism” and “Machiavelli” — in that order — with the first providing a screen for the second. “Machiavellianism. A word never pronounced without a shudder.” Then: “Machiavelli. One hasn’t read him but thinks him a scoundrel.” 13

It’s all in how you look at him, then. And why not take a look at him for ourselves, fearlessly; why not lift the mask to see the monster? We need only read his works to actually meet him, this man who was so intensely a part of his own time, and who for that reason continually invites himself into ours. Nothing is easier, in fact, because Machiavelli doesn’t bother to hide, unless it’s behind the banality of his own existence. But when he talks about himself, he does so frankly and in no way underplays his loneliness, his joy, or his doubts. Here, for instance, are a few lines into which he pours his troubles:

I hope and hope increases my torment,

I weep and weeping feeds my bruised heart,

I laugh and my laughter does not touch my soul,

I burn and no one sees my passion

I fear what I see and what I hear,

All things bring me renewed pain.

Thus hoping, I weep and laugh and burn,

And I fear what I hear and see.

14

Peter Paul Rubens, Portrait of Lorenzo de’ Medici

THREE

1469, TIME RETURNS

NICCOLÒ MACHIAVELLI WAS BORN