Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

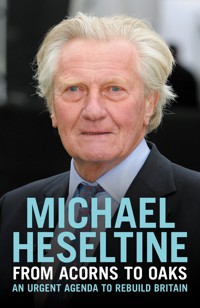

When Michael Heseltine wrote his acclaimed autobiography, Life in the Jungle, he assumed his political career was over. He returned to Haymarket, his publishing business, and intended to explore more of the world and pursue his passions outside politics. His assumption was wrong. David Cameron called him, tentatively at first but gradually with increased responsibility, back to the corridors of power. This second memoir is a potpourri of reminiscences about Heseltine's life and previously unexplored aspects of his stellar political career. But the main reason for Heseltine taking up his pen again has been to look back on the fundamental changes he was able to mastermind while in government and to set out the policies that are urgently needed to unite the country by driving growth, increasing prosperity and restoring hope. He combines this with new revelations about the seismic Westland scandal, the establishment cover-up that caused him to resign from Margaret Thatcher's Cabinet, and a damning assessment of what he considers the grievous act of self-harm inflicted on Britain by Brexit. This extraordinary new memoir offers an urgent agenda to rebuild Britain from one of our last great statesmen, who has been at the forefront of business and politics for the past sixty years.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 608

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

Contents

Introduction

This is not the book I had planned to write. My political career formally ended at the same time as the Conservative Party’s resounding defeat in 1997. I had plenty to look forward to – going back to Haymarket, the company I had helped found in the 1950s, and an increasingly absorbing garden to develop. I had been in the political trenches since I joined the Conservative front bench in 1967 at the age of thirty-four.

I had written of my experiences up to that 1997 election in my autobiography, LifeintheJungle, which was published three years later in 2000. Then, after the passage of more time, I started writing again, curious to explore whether I had achieved anything of consequence throughout my political life. That book was to be entitled ‘Building Blocks’, as much of my work was focused on urban regeneration.

But in December 2005, David Cameron became leader of the Conservative Party and in the following March, he invited me to accompany him on a symbolic visit to Liverpool. He followed this up with an invitation to chair a policy group and work up some ideas for urban regeneration for inclusion in the forthcoming manifesto. viiiAfter spending eight years in retirement from frontline politics, I was gradually, but not altogether reluctantly, drawn back into the mainstream.

‘Building Blocks’ was permanently put on hold after the election of the coalition government in 2010 and my subsequent appointment to chair the Regional Growth Fund, set up to help mitigate the consequences of the public expenditure cuts. That was followed by an invitation to join Sir Terry Leahy, recently retired CEO of Tesco, and investigate how the city of Liverpool had evolved from the place I had first explored after the riots of 1981.

For seven years, I served in numerous government roles, produced five reports and chaired many committees. This second lease of political life was a fascinating and privileged return journey to the corridors of power, which only ended when I was summarily dismissed by Theresa May for voting in the Lords, against the government’s wishes, for an amendment that would have given Parliament the final say on the historic disaster that is Brexit.

So, this book covers my brief return to private life, with the invitations that followed, the holidays we enjoyed, the obligations we took on and a feeling that the past is never really left far behind. I look at my return to the world of publishing, plus how I became deeply immersed in the development of the arboretum at our home in Thenford and the modernisation of our local village, which meant tackling, from the other side of the counter, planning and environmental regimes, many of which I had been responsible for introducing.

I also revisit my upbringing in Wales, and I reflect on what happened to all those important decisions I took in government, especially those which privatised more aspects of the public sector than any other minister.ix

This book also explores the long journey signposted by the phrases ‘levelling up’ and ‘devolution’, which began for me with the publication of the Redcliffe-Maud Report in 1969. Now half of England is governed locally by directly elected mayors and my report ‘No Stone Unturned’ can claim to be one of those signposts.

In 1981, I stood looking out over the River Mersey after the riots, wondering just how this grim series of events that ripped through the heart of the once-mighty city of Liverpool could have come about and what could be done about it. Here I have sought to revisit and re-examine my journey in striving to answer that question. From the streets of Toxteth to the banks of the River Thames, I devote a chapter each to our four great cities and the combined authority area Tees Valley, reflecting my conviction that transferring power from the monopolistic, poorly connected baronies of Whitehall to directly elected mayors is the only way to bring decisions closer to the voters who have to live with the consequences of them.

I have sought to look at a diverse range of policies, ranging from community gardening schemes to the establishment of the European Space Agency. Along the way, I steadily refined my understanding of the deep interrelationship between market and state and developed a distinctive analysis of what the state can – and cannot – achieve and what governments need to do to answer the biggest questions which still face our nation. How can we reinvigorate our once great provincial towns and cities, how can we re-energise our most deprived neighbourhoods and how can we rejuvenate our diminished industrial base?

Whatever economic dogmatists may claim, it is impossible to pretend that regeneration can be dissociated from industrial policy. I was determined not to allow my dismissal from government in 2017 to prevent me from participating in that crucial debate – not just xabout the nature of an industrial strategy but about whether such a strategy is at all credible – so I ultimately produced my own report.

I am, and always have been, a Conservative. I am deeply committed to the virtues and disciplines of competition. But the distinction between regeneration and industrial policy appears to me a stale and ultimately misleading dichotomy. I have learned that few viable markets can exist without the presence of the state and no modern state can excel without the dynamism of market activity. Technological innovation can often send entire city economies into soaring growth or a tailspin of decline.

Communities are also vulnerable to such vicious cycles. As indicators of dysfunction and instability rise, those that can afford to move away do so, further exacerbating the problem. But the actions of central government alone have, historically, rarely been successful in addressing these issues. All of these matters are examined in the chapters ahead.

There are some areas where I have been able to look further back. It is now nearly forty years since I resigned from Margaret Thatcher’s Cabinet over issues associated with Westland Helicopters Ltd. Little by little, the truth has emerged, revealing ever more clearly the scandal behind those events. I bring the story up to date here.

It would be unfair to move on from such experiences and leave unstated my gratitude and appreciation for the people who turned theory into practice: civil servants. They can be easy targets, ruthlessly exploited by those anxious to cover their own tracks. But I want to record here how grateful I am to them.

There is one matter where I look forwards. I feel it is essential to explain my view about our future relationship with Europe – a positiveand, in Tory terms, contraryview about Europe – which I do in the concluding chapters of this book.xi

I lived through the events after the Second World War, which inspired an end to a millennium of war in Europe. I grew up in the post-war world, where modern Europe was conceived, born and given substance. I took part in the 2016 referendum, the result of which left an empty chair at the table of European power and left an intellectual vacuum at the heart of Britain’s government. I now have to listen to those responsible for this debacle scrabbling around to find excuses for their inability to honour their undeliverable promises, which I find most distasteful. The fightback is just beginning.

People often ask me whether I would go into politics again today if I was young. Many are surprised by the alacrity of my reply that I would, without hesitation. It has been a privilege beyond measure to be at the centre of the stage for over half a century and to witness the successes and failures, the ups and the downs. I hope that others may not have to start where I began, in the quest for effective regeneration of local economies and the creation of an industrial strategy.

We are a European power, and I have been privileged to support several Conservative Prime Ministers in the vision of ensuring conflict on our continent on the scale of the two world wars could never happen again. Thus, by joining a union of states who share that common belief, we acknowledge that, in a world of superpowers, sovereignty shared is not sovereignty lost but enhanced.

The dishonesty of the referendum and its consequences will continue to haunt my party until the younger generation restores this country’s historic role at the centre of Europe. That is the mission for the future, but most of this book looks back at what I have experienced and learned over the last five decades.

Michael Heseltine

2024 xii

PART I

OUTSIDE POLITICS2

Chapter 1

Out in the Cold

After stepping back from frontline politics following the 1997 general election, my autobiography, Life in the Jungle, was published in 2000. It concluded with the words I had used to end the pressure on me to stand for the leadership of the Conservative Party after the defeat of 1997: ‘I won’t do it.’

I have never regretted that decision. As I said at the time, I was looking forward to an executive role at Haymarket, which I had effectively left twenty-seven years before. There was the arboretum we wanted to develop and the book that my wife Anne and I had long talked of writing about its creation. These were exciting things to be done, and I had a clear view of how the rest of my life would work out.

From my childhood to the present day, I have enjoyed three careers that have interwoven as threads through my life: a love for the natural world, an entrepreneurial hunger and an ambition to become involved in politics. Life, of course, does not run on tram lines. A hotchpotch of unpredictable invitations and unconnected events were to take their place alongside my more predictable commercial activities and the development of the garden. The reader may find the way the narrative jumps from one subject to another 4in this chapter confusing. That reflects the way it happened. I have not tried to hide the lack of connection.

This begs the question of how to react to these events. Inevitably, someone of my age is often asked by young people for advice about their careers. It is an impossible question, as usually you know nothing about their talents, interests and background. But I do have an answer, drawn on my experience, that I use as a response: ‘Do something that enables you to look forward to Monday morning.’ It has been my single good fortune that, with the one exception of the eighteen months spent as an articled clerk at Peat, Marwick, Mitchell & Co. in 1955, every job I have had combined two or more of my three driving interests. The advice seems sensible, even directed at a very different generation than originally conceived.

My childhood was spent within easy reach of the Gower Peninsula in Wales, with its pristine beaches of Langland, Caswell, Three Cliffs, Horton and Rhossili. My grandfather walked me up the Clyne Valley while we watched the elvers battling their way upstream, and I was fascinated by the collection of canaries and British finches in Brynmill Park.

At about the age of eight, I was sent to the junior school of Bromsgrove situated in Llanwrtyd Wells. I hated my time there and ran away with another boy, Kellen Scott, intending to hitchhike the forty-eight miles over the Sugar Loaf mountain to Swansea and home. Unfortunately, the first car that stopped was driven by the headmaster – so I left and was sent to another preparatory school, Broughton Hall in Staffordshire. It was a magnificent black and white Tudor mansion situated in spacious grounds. The birdlife there was plentiful and I organised a club of budding ornithologists, which was called the Tit Club. I have guarded with my life the fact that every member was known by the name of one of the species, 5for fear that my designation as Great Tit would have provided endless material for merciless parody and ribaldry by political friend, foe and media alike.

The war was our ever-present backdrop. One of the house mistresses had a strong foreign accent – she was French, but the view gained currency that she was a German spy. Every night we would use Morse code to interpret the vocabulary of twits and twoos of the local owl population to produce evidence for our conviction. We meant no harm, but looking back, it was shameful and explicable only in the context of the time.

My hobby expanded significantly when I later became a student at Shrewsbury School. My friend Robert Wild and I spent hours luring unsuspecting blackbirds into traps so that we could put very light, numbered rings on one of their legs on behalf of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. I hand reared jackdaws and a magpie, collected from nests as they were about to fledge. My parents were left to look after a cage of forty budgerigars when I went back to school.

My sporting skills left everything to the imagination. As a high jumper, my height of 6ft 2in. gave me something of a head start, but I was nowhere to be seen on the cricket and football playing fields, which are so important in such a school. But the devil makes work for idle hands. I would buy large bottles of multi-flavoured lemonade from the local Post Office, then sell it on at a significant profit to my more strenuous colleagues as they returned from their physical endeavours.

Of course, these examples range from the trivial to the absurd, except that they reveal a lifelong love of the natural world and a restless entrepreneurial energy that was to characterise my adult life. When I left high office in 1997, there was no doubt what I would 6do. Not all my colleagues have such clarity or opportunity. Many of them made huge sacrifices to pursue a career in public service. Nothing infuriates me more than the slick generalisation that politicians are only in it for what they can get out of it. Margaret Thatcher, John Major, Geoffrey Howe and Douglas Hurd, to name four among many, could have enjoyed far bigger incomes outside politics.

My advice to anyone invited to serve in some prestigious sounding role in a national or international organisation is to read the small print. The chances are that you are being offered a high-sounding position without power, the sole purpose of which is to raise funds. There is nothing wrong with that but don’t automatically assume that it is your intellectual ability and experienced decision-making that is being solicited. I was offered the chairmanship of the Royal Academy, which should not be confused with that of the president. What they really wanted was a fundraiser, and that was not for me.

Perhaps more predictable is the suggestion that you might write your autobiography after leaving politics. The money is often good but more important is to remember the thought expressed so clearly by Winston Churchill when he said that he knew what history would say about him because he intended to write it. So, get your side of your story into print because all of us in writing our autobiographies will be presenting our view of events rather than yours. You will not always be pleased when reading your colleagues’ account of what ‘happened’ during events in which you were involved.

• • •

In 2003, I was deeply flattered to receive an invitation from Mary Soames to deliver a tribute to her father Sir Winston Churchill on 7the fiftieth anniversary of the Cold War summit he held in Bermuda in 1953.

Churchill had persuaded General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the newly elected President of the US, and the Prime Minister of France, Joseph Laniel, to attend a summit meeting in Bermuda, a British colony off the east coast of America. Of course, Churchill and Eisenhower knew each other well – Eisenhower having spent some time in England during the war preparing for the D-Day invasion in 1944, as the Supreme Allied Commander of the whole operation. The main purpose of the meeting was to discuss the desirability and possibility of a four-nation summit meeting to include the Soviet Union. Stalin had just died; little was known in the west about the possible intentions and actions of his successor.

After the Second World War, Berlin, the former capital of Nazi Germany, was divided into four occupation zones by the Allies, with the USSR controlling the east and the US, UK and France controlling the west. The division of Berlin was a key event in the Cold War and the city became a symbol of the division between east and west because it lay deep inside East Germany, which was occupied by the USSR.

A mere five years before the conference in Bermuda, the USSR had tried to regain control of all of Berlin. The right of access to the city by the western powers was by road, rail and air via three clearly defined narrow corridors through or above East Germany. Without warning, the Russians closed off the road and rail access by which most of the supplies to the isolated western part of the city were transported. This was an illegal and bellicose action that was only thwarted by the determination of the Allies, who instigated the Berlin Airlift. For over a year, US and UK forces supplied the western sector of the city by air from West Germany, enabling West 8Berlin to survive until the Russians backed down. The world was in a very dangerous state – and there was much to discuss at the summit.

I had first met Mary and her husband, Lord Christopher Soames, when he was our ambassador in Paris and I was Minister for Aerospace and Shipping in 1972. I had been invited to dine with my opposite number in the French government and word must have reached Christopher. Undoubtedly anxious about the risk in allowing this unguarded young minister to be entertained by the French, Christopher scooped up the arrangements so that they were under his control and we were all taken to the theatre to see Marcel Marceau, the famous mime actor. My wife shares my vivid memory of our ambassador being greeted from all sides of the balcony as he waved and bowed to the distinguished French audience as we moved to our seats.

To compose a speech about Churchill confronts one with the most obvious dilemma. It has all been said a thousand times before and by historians with detailed knowledge far in excess of mine. There is a cartoon depicting him relaxing in the south of France with Prime Minister Asquith, in which he is asking whether there is any news from home. The reply makes my point: ‘How can there be? You are here.’ My friend Julian Critchley once described his early impressions of Churchill, as a newly elected Member of Parliament, in the division lobbies of the House of Commons: ‘The usual chatting, animated mass of MPs stood apart to open a way through which the great man might pass. It was like watching history walk past.’

For my generation and many others, that is how we will always see him. I wanted to hear and see him speak in person and travelled to his Woodford constituency to listen to him address the annual 9general meeting of his local Conservative party in the late 1950s. I stood in Trafalgar Square in January 1965 to watch his cortege pass by. I have visited his grave in St Martin’s Church, Bladon, near Woodstock, and his birthplace, Blenheim Palace. I have also delivered the annual speech in his memory at Harrow School, where he had been a pupil.

Churchill’s conference in Bermuda perpetuates a memory of an extraordinary man whose life and influence are inseparable from an extraordinary century, a century that saw the zenith of British power and influence and in which he played a legendary role. Churchill had three great political passions: Britain’s monarchy and empire, Britain’s special relationship with the US and Britain’s place in Europe. He brought his powers of oratory to celebrate the fact that such a diverse group of nations, forged in history by the military, economic and diplomatic interests of an island off the west coast of Europe, could see that it was in their own self-interest to remain bound by the bonds of Commonwealth. His famous phrase of ‘To jaw-jaw is always better than to war-war’ has its relevance in the evolution from empire to Commonwealth.

The bonds of language, law and democratic parliamentary government would be for him a lasting source of pride. He would proclaim that, despite the excesses and mistakes of imperial rule, our creation and leadership of the empire bequeathed a legacy where the balance between good and evil is heavily weighted on the side of virtue. His eyes would fill with tears as he reminded his grandchildren of those who joined so selflessly and sacrificed so much to keep alight one island of hope in mid-twentieth-century Europe. There were so many. Canadians and Rhodesians in the skies over south east England in the Battle of Britain; Australians and New Zealanders in the deserts of North Africa; Indians, Punjabis and 10Gurkhas along the Irrawaddy River in Burma and at the frontiers of India itself; and many others.

Would Churchill recognise the US of today? It is no longer the world’s only superpower and in many ways it is a very different country to the one he knew. It is so diverse, so interwoven with different interests and alliances. However, it is the fundamentals of politics, the rule of law, the love of freedom, the human rights of citizens and the ability to communicate in a common language that keep our countries so close.

As another Trump presidency raises questions about the cohesion of the US itself, as well as the NATO alliance, Churchill would remember the pressure exerted on President Roosevelt in 1940, which made him promise not to enter the Second World War. It was Hitler’s fatal mistake in declaring war on the US that brought them into the war and ensured the ultimate liberation of Europe.

It has been my privilege to know something of Britain’s relationship with the US. I was Secretary of State for Defence through the height of the tensions that surrounded the modernisation of NATO’s nuclear weapons in the early 1980s. I don’t believe any of us realised at the time that what was at stake was not just the right to maintain our deterrent capability but the future of the USSR itself. For seventy years, Pax Americana has served the US well, but it has served the world well too. The US has invariably looked to Britain for support where British interests and experience coincided with its own. Only once has that support been denied, when Harold Wilson rightly refused to send British troops to Vietnam. But, as every true friend would, I think Churchill would today use words of caution about what is perceived to be a recent – and coming – shift in American policy.

Churchill, above all else, was a man convinced by the need for 11international institutions to guide our international behaviour. A strong believer in the United Nations, as well as the need to draw the nation states of Europe into ‘a kind of United States’ and the need for the resolution of disputes everywhere by dialogue, he would, I think, have wondered at a range of decisions that seem to be differentiating the US of today not only from the US of yesterday but from much of the rest of the world. Of course, he would have respected the right of a rich, strong nation to pursue its own self-interest. No one understood better than he did the loneliness of great power. But the change over the years in the US’s approach to various international accords such as the Paris Agreement, the Law of the Sea Conference, the ABM Treaty, the anti-personnel mines convention and, of course, the issue of Iraq seemed totally at odds with their past policies. The concern over a Trump presidency’s approach to global warming is a recent example.

In my tribute to Churchill in 2003, I made clear my support for American policy – first in the joint decision, supported by United Nations resolutions, to eject Saddam Hussein’s Iraq regime from Kuwait after his illegal invasion there in 1990 to try and grab Kuwait’s oil fields. I also fully backed American policy in Afghanistan after the 9/11 attacks in New York in 2001, an act of shocking terrorism.

On the other hand, the decisions which led to our invasion of Iraq were of a different order. George Bush and Tony Blair, the two heads of government concerned, had, without the public or their governments being aware of it, made a decision that Saddam Hussein must be removed. This was at first a secret deal, which had momentous consequences.

To go to war in order to achieve regime change is not, apparently, against US law. But it is against the laws that cover the actions of 12British forces, and Blair’s agreement with Bush caused the Labour government to get into the most fearful muddle. The Attorney General had to be persuaded to change his initial advice to the Cabinet that British actions in the circumstances would be illegal; a document was produced, attempting to justify the proposed invasion, which contained matters that were untrue to say the least; and the arguments continue today as to the validity and legality of the actions that the two governments ultimately took.

The crucial question was whether Saddam had, or was attempting to develop, weapons of mass destruction. That he had chemical weapons was beyond doubt; he had used them on the Kurdish population in his own country. It was known that he was preparing to manufacture the materials to make nuclear weapons, but he had concealed whether, or how far, he had succeeded in this quest.

A resolution was passed in the United Nations ordering Saddam Hussein to allow UN inspectors into Iraq, with the freedom to examine all of the industrial facilities concerned with the production of enriched uranium. The weapons inspectors duly entered the country to start work. The US, backed by our government, complained to the UN that the inspectors were being prevented from doing their job by Iraqi intransigence and interference, and they presented a further resolution in the UN authorising the use of force.

This resolution was defeated, and it was then that the US and UK decided to proceed without the backing of a UN resolution. The UN inspectors left, their job incomplete, and the invasion took place. The rest, as they say, is history.

In the aftermath of the war, no weapons of mass destruction were ever found, but the overthrow of Saddam, and the way the consequences of the war were handled, upset the stability of the whole of the Middle East with unpredictable consequences for all.

13Nations must be free to exercise their sovereign rights, but we must also ask the question: what is sovereignty in today’s shrunken world?

We all know what it used to mean. It meant sending armies across frontiers or navies across oceans into conflicts with real or imaginary enemies. But nuclear deterrence, often aptly described as ‘mutually assured destruction’, has eliminated the concept of victory for anyone without unacceptable consequences.

In tomorrow’s world, the greatest threats will not be those which need to be overcome by military might. Global warming, illegal production and distribution of drugs and the organised crime which controls that evil trade, international terrorism, tax evasion, cyber warfare; the regulation of global capitalism, the exhaustion of natural resources, population explosion, people trafficking and protectionism. All these problems can threaten every one of us, but they are also beyond the power of any one nation state to solve alone.

True sovereignty – the sovereignty that enhances security and power – will increasingly be a sovereignty that nations voluntarily share and enjoy collectively. Britain faces these issues most acutely in our relationship with our European neighbours. Churchill is often portrayed as a loner – his phrase ‘Very well then, alone’ created the famously defiant image of Britain in 1940 – but that was not an isolation of his choosing. No man was more proud of his country, its history, and the institutions and the relationships that bind us together. He was one of the first to advocate what he called ‘a kind of United States of Europe’. Some seventy years later, the question remains as to what that means.

• • •

14As I said earlier in this chapter, the reader will notice the seemingly random reminiscences which follow about my love of the countryside and country sports. I shot and fished for many years. I never actually hunted but fully supported those who did. The controversies that surround the issue of field sports continue to increase and I want to point out not just the influence that the countryside and its flora and fauna have had on me but how important it is that the balance between man and the environment in which we exist needs constant nurturing if both are to prosper.

After the Second World War, my father’s return to civilian life in 1945 opened a quite different opportunity. His uncle Sam Stride, a prominent Swansea jeweller, and his father owned rights together over a stretch of the River Towy, where my father would take me to learn to fish. The thrill of choosing the appropriate fly, learning to cast or the jerk of a bite in a real river was of a different order of excitement from any that I had experienced during the war. I loved sitting on a stool alongside a pond, fixing maggots to a hook at a fishing competition in Brynmill Park. I won that early fishing competition but not due entirely to my skills with the rod and line. I had used up about half the time available with nothing yet in the net. There were plenty of bites, but cunning fish managed to devour the bread paste from my hook without being in danger of capture.

‘Try one of these,’ said a voice, as Mr Kiley, who worked for my grandfather, handed me a tin of wriggling maggots. When the whistle finally went, I had caught thirty-nine fish, a total of 11.75 ounces – enough to earn me a silver cup and seven shillings and sixpence, having outperformed the next competitor. I had hoped that after my father’s death in 1957, this fishing beat would still be available to me and was deeply disappointed when Stride rejected my request.

My lifelong love of fishing has continued ever since. Over the years, 15I have collected many unforgettable memories – including frequent visits to the River Tweed with Lord Ridley, nephew of my colleague Nicholas, and Sir Simon Day, a distinguished West Country politician, to the Rivers Naver and Helmsdale with Sir Max Hastings, a newspaper editor and historian, and as a guest on the River Test and the River Kennet.

In a class of its own must be the week I spent fishing one of Russia’s great salmon rivers. In 2005, Sir Christopher Bland, chairman of the BBC, and Max Hastings took me to western Russia to two of the great salmon rivers, where a very comfortable but basic set of wooden huts provided the accommodation. It was a particular pleasure for me that they invited my son, Rupert, to join the party. The trip was organised by Roxtons and we were under the leadership of Charlie Wright. All seemed to be progressing smoothly until we approached Murmansk, our destination but also a centre of Russian nuclear activity.

The first intimation that something was wrong was the slowing and circling of our aircraft. Charlie came on the intercom to explain that there was a mistake in our flight particulars and that we did not have permission to land. We were escorted out of Russian airspace by two MiG fighters to an obscure provincial airport in Finland, where we landed amid some unfavourable local flooding. Charlie needed to get us back to Murmansk, which meant enduring one of the most uncomfortable journeys of my life in a tiny bus until 4 a.m.

Actually getting into Russia another way required some skill in itself as the frontier guards were quite unprepared for a party like ours. However, offerings of meat, drink and confectionery had an eloquent persuasiveness. We made it in time for our helicopter trip at the final stage of the journey, which took place in an ex-military aircraft that did not seem to be compatible with the threat about which I had been briefed all those years ago.

16The Rivers Lower Varzuga and Kitza are huge and teeming with fish. In total, we caught 137 on the former and eighty-seven on the latter. I came bottom of the class with sixteen. They all had to be put back, as we were not allowed to keep what we caught. The competition was won by Major General Nick Ansell, who had figured out that the fish would seek the relatively less powerful flow close to the bank. He caught forty-four.

Naturally, I was interested to explore the views of my Russian ghillie. ‘You must find your new freedoms more attractive?’ I suggested. ‘Communism was better,’ came the reply from someone exposed for the first time to the workings and uncertainties of the market and unenchanted by the glasnost and perestroika that had brought it about.

If there was plenty to occupy my time, there was also the chance for holidays. One of the privileges that flowed from ministerial office, and indeed from executive responsibility for Haymarket, was the ability to combine political or business visits with the chance to explore the countries to which my career took me.

Visits to the Falkland Islands resulted in spectacular sights of the massive penguin colonies there. Selling tornado aircraft to Saudi Arabia took me deep into the deserts in search of birds of prey. Anne and I combined official trips with holidays in Barbados and Australia where we learned to scuba dive, first in Barbados, then off the Great Barrier Reef and then in the Red Sea, where the coral reefs were at their best and before the consequences of global warming caused the El Niño phenomenon to bleach them white. We also enjoyed a trip, again organised by Max Hastings, in a chartered yacht to the Galapagos Islands. Among the most famous birds to be seen there is the blue-footed booby. The name was immediately adopted for our party, which included Ken and Gillian Clarke, Douglas and 17Judy Hurd, Anne and me, Jeremy and Gillian Isaacs and Caroline Waldegrave. Listening to Gillian Clarke singing music hall ditties or being instructed in the finer arts of bridge by Caroline are treasured memories.

We were not an undistinguished or irresponsible group, but we had a young German guide in her early twenties who insisted every morning that ‘Ve vill haf ze briefing’. After two or three days of this, during which we were lined up like children at school, Ken Clarke was deputed to try to explain to her the depth of experience of her audience. The next morning, we waited with expectation. Nothing changed. ‘Ve villhaf ze briefing,’ she insisted.

Quite rightly, the conditions for such visits are tightly controlled and paths clearly marked because of the rare and fragile ecosystem there, but the experience of mixing with birds and seals who have no fear of humans is unforgettable. On one occasion, I was photographing the finches which Charles Darwin had made famous, but not to be outdone, one of them perched on my lens, thus posing the question as to who was watching whom.

• • •

My first shooting experience was with my father in 1943, when he was commanding a battalion of Royal Engineers based at Shotover House near Oxford. He had set himself the impossible task of firing a .22 rifle at the tiny wriggling heads of grass snakes in the lake.

Moving on from that childhood experience, I never had a lesson with a shotgun, but I started using them with my friend Simon Day in the mid-1960s and other invitations followed. I found it hard to understand that the essence of the sport is to swing the gun through the target before you fire and thus have a chance of hitting it. I was 18shooting at the bird and, of course, by the time I pulled the trigger the bird was no longer there. My colleagues, after each drive, would busy themselves collecting what they had shot. I was not one for hanging hopelessly around, so I devoted myself to collecting my spent cartridges. How it happened I will never know, but I did eventually hit a pheasant and proudly, at least to myself, I was able to record one bird for twenty-nine shots. Thus began a practice that remained with me to the end of my shooting career. While others would talk in general terms about the quality of each drive, I knew precisely my score. I was satisfied to maintain a record one bird for four shots in my last drive ever.

I was very fortunate to shoot with good friends at some of the best shoots in the country, over forty years or more – but you know when it is time to quit. That first stumble as you fire, or the cold of January, together with a growing sense of sympathy for the pheasant, increases the frequency with which you ask yourself, ‘Why am I doing this?’ So, I gave up in 2023 and have only one regret: Fred, our labrador, cannot understand why he is a gun dog no more.

I have from my earliest teenage days viewed horses with some suspicion. They are a long way from the ground, and while I respect – indeed, admire – people’s ability to control these magnificent animals for their social and physical pleasure, I have long believed that God gave me feet to keep me firmly on the ground. Nevertheless, that in no way blinds me to the contribution of the hunting fraternity to the countryside and its people. The countryside is not a Walt Disney world. Foxes are vicious and cunning predators. They hunt not only to survive (farmyard chickens, ducks and newborn lambs are attractive items on their menu) but, unlike most other predators, they kill for pleasure, not just enough to feed their families.

The problem is that foxes have no natural predator and the issue, 19therefore, is how to control their numbers. There is no humane, gentle way to achieve that. Snares, poison and shooting can all inflict cruelty and pain. I spoke from the opposition benches in the House of Commons when we debated the Wild Mammals (Hunting with Dogs) Bill in November 1997 and again in 2000, where I made the case that the hunting ban was not about animals:

The fact is that there are deep class resentments in the anti-hunting lobby. Let me make a simple point. Those who will suffer from the ban that the Labour Party wish to impose are not the rich, not the toffs. Those people’s horses will go to Ireland or to France. There will be chartered aeroplanes to take them wherever the sport can be found, and given the growing affluence of which the Labour Party is so proud to speak, they will find ways of continuing. Those who will really suffer are ordinary people in rural communities – the people who stand and watch, and whose social life revolves around the hunt. It is they who will find that a great part of their lives has been removed from under them.

• • •

Let me now return for a moment to some special memories from my Oxford days – in particular, those of one of my oldest friends.

My friendship with Anthony Howard began when we both held office at the Oxford Union. Tony and I remained at opposite poles of the political spectrum, but I always admired the journey his career had taken him on. He started in journalism on the old Reynold’sNewsbefore moving to TheGuardian, the SundayTimesand then TheObserver, where he served as Washington correspondent during the turbulent years of Lyndon Johnson’s presidency. He then 20returned to London and moved to the NewStatesman, which he edited for six years from 1972. A spell editing TheListenerwas followed by a return to TheObserveras deputy editor. He moved to TheTimesin 1993 as obituaries editor. I shared his disappointment that he narrowly failed to edit TheObserver, a post for which he was admirably suited.

When Tony died – far too early – at the age of seventy-six in 2010, I was anxious to provide a fitting tribute to his memory. Sir Jeremy Isaacs, another friend, contemporary and office holder in the Oxford Union, was an extremely successful television producer and executive at ITV, with credits including TheWorldatWar, before becoming the founding chief executive of Channel 4. During our Oxford days, both he and Tony Howard played a major part in helping to get me elected president of the union. These were friendships that transcended party politics; at the time Isaacs and Howard were chairman and chairman-elect of the Oxford University Labour Club respectively. Isaacs came up with the idea that Haymarket should create a unique award: an annual bursary of £25,000 for an aspiring journalist under the age of twenty-five, who wanted to write about politics and government. We hoped this would pay homage to Tony’s innate ability to spot talent. In his time at the NewStatesman, he recruited a dazzling roster of writers, including Martin Amis, Christopher Hitchens, Julian Barnes, James Fenton and Patrick Wintour.

I approached the editors of the three publications with which Tony was most closely associated – TheTimes, TheObserverand the New Statesman – and they readily agreed to host the successful candidate in successive fourteen-week fellowships, working alongside their political staff in the Westminster lobby, where they would gain rare insight into Westminster, Whitehall and the workings of 21government. Applicants would be required to propose a political subject for in-depth enquiry and detail how they would go about their investigations. And remembering that Tony always valued sharp, lively copy (‘Do me a flashy piece,’ he would say to contributors), they would also need to provide a good example of their writing.

The award, which would run for five years, would be judged by a committee under Jeremy’s chairmanship, consisting of the author and former political editor Robert Harris, the constitutional expert Peter Hennessy, the TV presenter Jeremy Paxman and the biographer Claire Tomalin. We were particularly fortunate to secure the services of TheObserver’s Stephen Pritchard, who masterminded the process throughout, working his way through the numerous applications (averaging about 100 a year) to present the judges with a shortlist from which to choose candidates for interview.

One day it will be possible to chart the complete career journey of each winner, but already it is evident that the judges chose some notable young talent, all of whom are stars in British political journalism. Lucy Fisher, the first winner in 2013, set the bar high for later applicants. She went on to work as a political and defence correspondent at TheTimesand the DailyTelegraphand is now Whitehall editor at the FinancialTimes. Ashley Cowburn, our second winner, became a political correspondent at TheMirror. Henry Zeffman, who won in 2015, became the BBC’s chief political correspondent after a lengthy spell at TheTimes. Patrick Maguire, the 2016 winner, returned to TheTimesafter working as a political correspondent at the NewStatesman, where he is now one of their star political columnists. Dulcie Lee, who won in 2017, is a senior journalist at the BBC. And in 2018, the final year of the award, Eleni Courea won and joined TheGuardianas a political correspondent 22after working for The Times and Politico. Anthony would have been proud of all their work, continuing in his fine tradition of sparkling, enlightening political journalism.

Writing of Tony reminds me of the debt that I owe to Oxford University. I arrived as a typical product of the school system, middle class with a provincial background and a record of achievement that was best left undiscussed. I must have conveyed a certain confidence, nevertheless, as I was offered a place in Pembroke College, Oxford, and St John’s College, Cambridge, on the basis of my school certificate results and an interview. I chose Oxford as I could take up their offer immediately, whereas Cambridge insisted that I should complete National Service first.

It was a new world for me, free of the regimentation of boarding school and made up of people from diverse backgrounds and with every shade of political opinion. It was up to you to pursue whatever opportunity appealed to you.

I spent most of my time in the Oxford Union. I once heard that George IV said of the Head Boy at Eton that you are greater now than ever I could make you. I quoted this remark in my last term as president of the Oxford Union during my retirement speech to explain how privileged I felt to have that position bestowed on me so young. I ultimately obtained a second in Politics, Philosophy and Economics at Oxford, described by my tutor as a great, but undeserved, triumph.

The renowned athlete Roger Bannister, the first person in the world to run a mile in under four minutes, later became master of Pembroke and conferred on me an honorary fellowship. A subsequent master, Giles Henderson, undertook a very large development of the college facilities, and I was particularly pleased to be able to endow two student bed-sitting rooms in memory of my parents.

23In 2024, my wife and I joined the former Appeal Court judge Sir Ernest Ryder, who is now the master, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the foundation of the college. Over the years, I have frequently returned to participate in debates in the Oxford Union, which are conducted very much to the pattern I remember. In November 2024, I was invited to propose the motion ‘This house would rejoin the European Union’. Unfortunately, before the debate could begin, a point of order was raised under an arcane rule, which led to an interminable debate about union rules. After more than an hour of this, and with no prospect in sight of an early return to the main business of the day, I left. Behaviour of this sort, if repeated, will deter visiting speakers and a generation of undergraduates will lose the opportunity to listen to men and women who have served at the forefront of their profession.

In 1999, the House of Commons art fund commissioned a bronze bust of me for their collection. It was sculpted by Anne Curry, wife of David, a friend and colleague in the House. The Oxford Union now has one of the six copies which were cast, and we have another.

The Oxford Union celebrated its 200th anniversary in 2023. I was invited to speak at the dinner. Among the guests were many ex-presidents, including Theresa May and Jacob Rees-Mogg. It was with no small pleasure that I concluded my speech by saying that I hoped that this great centre of learning would be a leader in the fight to restore the country back to the heart of Europe, which was greeted with thunderous applause.

• • •

When I was first elected in Tavistock in 1966, we were aware that the constituency was likely to disappear in the forthcoming boundary 24changes. Sir Peter Mills was the incumbent in the neighbouring seat and was likely to want to contest the new, enlarged constituency. So I was aware that if I wanted a lengthy career in politics I should have to look elsewhere. I was selected for the Henley constituency in 1972, elected there in 1974, and Peter duly became the member for West Devon, which included much of my former seat. So that now identified broadly the area within which my wife and our family could settle. I was travelling by plane to Edinburgh when someone quite unknown to me, David Fleming, approached me to ask if I would like to buy his house, which he described as the ugliest house in England. We bought Soundess House in Nettlebed, Oxfordshire in 1972. It was wonderfully situated in the heart of the Chilterns and our purchase also offered the opportunity for my mother to move closer to her family. She sold her home in Swansea and moved to the Fairmile, just outside Henley.

From that time, my visits to Swansea became rare and always for some specific purpose. It was therefore with particular pleasure that in 2001, I received a letter from Robin Williams, vice-chancellor of the University of Wales, Swansea, inviting me to accept an honorary fellowship. It was a night of memories for me as I was able to invite my cousins, Gillian and Jimmy Pridmore. Robert Hastie, one of my oldest friends, attended the event in his capacity as Lord Lieutenant. I was equally pleased to be invited, in 2004, by the same university to give the annual lecture that had been established to honour Jim Callaghan, the former Labour Prime Minister.

I served in the Commons at the same time as Jim, but we were on opposite sides and he was of an older generation, which would normally have made for a somewhat distant and formal relationship. However, in this case, one event changed all that, as I was able to recount in my lecture. My daughter Alexandra, then aged eleven, 25had made an aggressive intervention in my political career. She had been so incensed by some comment she had read, which had been attributed to Jim, that without saying anything to her parents, she wrote a blistering letter to the Prime Minister. ‘That Callaghan’ had become a mortal foe as a consequence of what she thought was his totally unwarranted attack on her father. The response from No. 10 was immediate and electric: a letter of charm and courtesy that was followed some years later by an invitation to lunch in the House of Lords. Jim had won a lifetime admirer.

I also referred in the speech to one of Jim’s less fortunate experiences. As Home Secretary, he was bound to put the findings of the Parliamentary Boundary Commission to Parliament. Its recommendations were unfavourable to the Labour Party and he was responsible for whipping his party into the lobby to vote down his own proposals. His letter to me following my lecture included an interesting comment about the event:

You are kind in your comments about the ‘political curiosity’ of a Home Secretary voting down his own proposals. That was not the proudest moment in my political life. It arose from what happened in the 1945 Parliament, when Chuter Ede, with some gusto, set about redrawing the parliamentary constituencies. The redistribution was so sweeping that only eighty seats were left untouched and, on the Labour side, we thought we had been badly treated. The reverberations continued for many years and were at the root of what I did when I was Home Secretary and was determined not to repeat Chuter Ede’s experience. That is an explanation not an excuse.

I was glad he was able to write about my lecture and say that he 26agreed with my analysis of the global situation. He was a good man who has a special place in our family.

• • •

These seemingly unconnected recollections have a habit of returning periodically to my connections with Wales, which go back right to the early days of my life. Fate has intervened on a number of occasions to take me back there – for very different reasons.

It is one of my few regrets that I was born with no musical talents at all – and that is an understatement. It was not for the want of trying. I attempted to learn the cornet and later the piano. I was the only boy ejected from a choir of the whole house of forty boys following a detailed audition by the music master. It was thus a special pleasure to be invited to become a patron of the Morriston Orpheus Choir. This honour has brought with it many happy memories, including their presence at Alexandra’s wedding, the nostalgic evening in 2016 when we remembered one of the worst bombing attacks on Swansea seventy-five years earlier, and their singing at my ninetieth birthday party.

• • •

My ministerial career did not cover the devolved Welsh Principality, although I was delighted when my colleague Nicholas Edwards made good use of my ideas by establishing the Development Corporation in Cardiff’s Tiger Bay and a garden festival in Ebbw Vale.

With the return of the Conservatives to government, leading the coalition from 2010, I gradually became more involved in the regeneration of rundown areas and the consequences of industrial 27decline. It was a particular pleasure to me, therefore, to receive an invitation from Alun Cairns, Secretary of State for Wales, in March 2017 to become involved in the project to redevelop Swansea Bay. I was fully briefed and presented with the detailed plans. A meeting was arranged for 8 March, where I was to accompany the ministerial team in holding extensive local consultation and explore the site. An agreement was reached about the role I was to play. But in the House of Lords the night before, I voted to give Parliament the final say on any Brexit deal. I was duly sacked and so ended my opportunity to play a meaningful role in Welsh affairs – or so I thought.

In 2019, the First Minister of Wales invited me to chair the external advisory group for a new National Forest for Wales, but with the looming Brexit chaos and the prospect of reaching the age of ninety, I had to acknowledge that I did not have the energy or the time for the task, so I reluctantly declined the offer.

In the spring of 2024, the troubles with steel production at Port Talbot made daily headlines. I was invited to see David T. C. Davies, then the Tory Secretary of State for Wales, for a discussion. I thought it wise to suggest they first clear the invitation with No. 10 in case there was any hangover from the past. All was well. Presumably my earlier regeneration experiences, particularly with the SSI steelworks in Teesside, influenced the invitation. The date and details were all in place when Rishi Sunak called the election. I was very sad not to be able to play what could have been one last useful and important role in the place of my birth.

However, now fate has once again intervened. I have been asked by Jonathan Reynolds, Secretary of State for Business and Trade in Keir Starmer’s new government, to join him on a visit to the site. No date has yet been arranged, but I am thrilled at the prospect and it will resurrect memories of my visit there with my father in the 1950s.28

Chapter 2

Back to Haymarket

Starting and developing a business from scratch is at the heart of the political philosophy of wealth creation for any Conservative. Of course, there is a natural attraction towards the benefits that success can bring, and certainly the sense of security and independence encouraged me as I contemplated the unpredictability of a political career.

There is, however, much more to it than that. The existence of a wide spread of independent wealth is an important counter to the extremes of state-based societies. Family-owned companies start and largely remain close to their local communities. Paternalism is out of fashion, but I think its critics lose sight of important relationships. Certainly, the closeness of the great landlords to their estates in this country saved us from the horrors of the guillotine spreading from revolutionary France over 200 years ago, but it did much more than that. Proximity encourages awareness – a sense of community, obligation and responsibility.

At their extreme, the family businesses of today – Sainsbury’s, Morrisons and John Lewis – echo the great Quaker businesses (the Rowntrees and Cadburys) of Victorian England, but there are 30countless examples of many smaller companies providing outreach activities into their local communities. There is a stark contrast with the remoteness of the quoted company, often with their overseas management structures and shareholders. Investment companies often remunerate their managers with profit-related bonuses calculated on a quarterly basis. To them, the takeover is the ultimate prize.

I recognise the valuable role of these large, publicly quoted companies and the scale of community involvement in which many participate, but I remain firmly of the view that a large middle range of small and medium companies with their roots deep in the community is socially and politically important for a stable democratic society.

There is a strong entrepreneurial background to my family. In Victorian England, my father’s grandfather was a partner in a well-known grocer, Heseltine, Kearley & Tonge, while my mother’s father, James Pridmore, started his own business repairing machinery in the coal and oil industries. There were early indications that I inherited my instincts from them.

As a part of my drive to restore the finances of the Oxford Union, I had sublet a shed in the grounds to a fellow undergraduate, Clive Labovitch, who needed a place from where he could manage Cherwell, the university newspaper he had recently acquired. He invited me to become a director of the company and our friendship grew over long discussions in the president’s office about our future lives. One evening in 1957, when I was standing by the switchboard of the New Court Hotel in Inverness Terrace, which another Oxford friend, Ian Josephs, and I had recently acquired, I received a call. It was no surprise to hear the news that Clive had bought a business and would welcome my advice. I caught a cab and listened as he described to me what he had bought.