Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

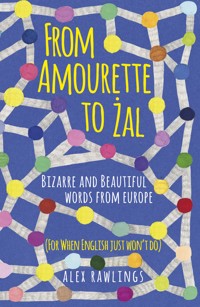

Fjaka: the sublime state of aspiring to do absolutely nothing. Warmduscher: a 'warm showerer', meaning a bit of a wimp. Tener mano izquierda: literally 'to have a left hand'; to be skilfully persuasive. For all the richness of the English language there are some nuances that other languages capture much better, whether it's a phrase that beautifully articulates a feeling, a wonderfully understated insult that just hits the spot, or a curious idiom. From the melancholic to the funny to the downright peculiar, From Amourette to Żal takes us on a fascinating journey around Europe in twelve languages, celebrating our cultural similarities and differences along the way.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 212

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To my parents, who first gave me the gift of life and then passed on to me their love for language.

Acknowledgements

With special thanks to Fanny Thalén, Eustacia Vye, Zsófi Geschwendtner and Gaston Dorren for help and linguistic insights.

First published 2018

The History PressThe Mill, Brimscombe PortStroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Alex Rawlings, 2018

The right of Alex Rawlings, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8966 4

Typesetting and origination by The History PressPrinted and bound in Great Britain by TJ International LtdeBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Introduction

French

Spanish

Portuguese

Italian

Greek

Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian

Hungarian

Dutch

German

Swedish

Polish

Russian

Epilogue

About the Author

INTRODUCTION

A WORLD WITHOUT GRENZEN

Die Grenzen meiner Sprache bedeuten die Grenzen meiner Welt

The borders of my language signify the borders of my world

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Austrian-British philosopher

The Wittgenstein quotation that opens this book is one that you might see regularly nowadays, popping up in internet memes, blogs, newspapers, and anything connected to language, learning languages, and multilingualism. However, if you have seen it before, you may remember a slightly different version of it. Conventionally, in English we tend to translate the German as: ‘The limits of my language are the limits of my world.’ Usually, there is no mention of the word ‘borders’ or ‘signify’, although broadly speaking the meaning of the two is still fairly close.

We understand in either version what Wittgenstein means. He is drawing attention to the fact that we can only truly know something if we have the language to describe it. If we don’t have a precise word for something, we simply put it under the umbrella of the most similar object we do have a word for. That is why, for example, English sees dark blue and light blue as two shades of the same colour, but red and pink as different. Russian, on the other hand, has two separate names for the two colours: синий (síniy) is dark blue and голубой (galubóy) is light blue. For Russian speakers, this is not only a difference of vocabulary. They consider the two to be separate colours.

Yet Wittgenstein’s choice of words in the German original is intriguing. Wittgenstein talks about Grenzen, which is primarily the German word for ‘borders’. It can be translated as ‘limit’, but only in specific circumstances. To do so is problematic, because German has two words for ‘limit’, where English has one. German distinguishes between a natural limit and an artificially imposed limit. The maximum speed that a human being can ever run at is a Grenze, while the maximum speed at which a car is legally allowed to travel on a road is a Begrenzung.

Importantly, in German the word Grenzen takes on far more significance than its translations would for most English speakers. A German speaker residing in Germany, Switzerland or Austria is surrounded by national borders on all sides. Certain generations will remember what life was like before the Schengen agreement of 1995, when cars were forced to queue for hours before they could cross to the other side, waiting for their documentation to be checked by the Grenzschutz, or ‘border control’. For half of the twentieth century, Germany itself even had a Grenze running down the middle of it, as the country was divided into East and West, with families and livelihoods severed on either side of the line.

To translate Grenzen as ‘limits’ in this case does not even come close to addressing the nuance that the word carries in German. So much meaning is lost, as unfortunately is always the case when we just look to the translation and ignore the original.

In the twenty-first century, English has become one of the most powerful languages in the world. It is hard to put a reliable estimate on just how many people worldwide speak it and to what degree, but undoubtedly it is the international language for business, tourism, politics, academia and almost all scenarios in which people from different countries need to communicate. The current trend is for this to increase, which means that wherever you go, there’s an ever greater chance that you’ll find someone able to speak and understand English.

Most native English speakers can hardly believe their luck. Through no achievement of their own, they are now able to cruise around speaking their language and feel as though everyone is able to understand them. As a result, all over the English-speaking world, people have stopped learning foreign languages. Those with traumatic memories of failing French tests at school now feel increasingly vindicated that ‘it was all a waste of time’. Nowadays, even French president Emanuel Macron is happy to use English at press conferences, in stark contrast to his staunchly Francophone predecessors.

There are a number of reasons why this prevailing attitude is not only mistaken, but even damaging.

Firstly, although from an Anglophone point of view the world is becoming increasingly English speaking, from a global point of view the world is actually becoming more multilingual. Thanks to easier access to international media through the internet, an unprecedented boom in international travel and heightened awareness of the importance of doing business with other countries, more and more people around the world are learning to speak another language. It’s just that the language they’re learning happens to be English.

Multilingualism around the world is becoming the norm, and scientific research is showing incredible data about its health effects. The mental gymnastics required to pick up another tongue have already been proven to greatly increase cognitive abilities among multilingual people. In 2013, a report published in the journal Neurology showed people who spoke more than one language – including those who learned one later in life – even delayed the onset of dementia by four and a half years on average, compared with monolingual people.

So long as the cultural attitude persists that, because English speakers have somehow won the ‘linguistic lottery of life’, they are exempt from the need to learn other languages, how will they reap those benefits? Meanwhile, in other countries around the world the ability to speak more than one language is increasingly becoming as commonplace as literacy and typing skills were a hundred years ago.

Secondly, there is always a risk of assuming people are learning your English. The reality is most people probably aren’t. They’re learning their own English. They’re keeping their own language and swapping out words for English equivalents, while strongly retaining their own identity and perspective on the world. Before our eyes, brand new dialects of English are springing up everywhere, which are already leaving native English speakers as baffled as if they were being spoken to in a foreign language.

People’s native languages don’t simply disappear when they start learning another language. They remain a constant reference point for whenever they need to express themselves in any language and will always strongly influence the way they speak them.

That’s why, for example, Greek speakers often start questions in English with the word ‘maybe’, because they’re searching for an equivalent for the word μήπως (mípos), which is always used to start a polite and formal question. ‘Maybe you would like something to drink?’ is a word-for-word translation of the Greek phrase ‘Mήπως θα θέλατϵ κάτι να πιϵίτϵ;’ (‘Mípos tha thélate káti na pyíte?’).

That’s why French speakers often ask questions without changing the word order. Although it might sound rude or presumptuous in English, in French you don’t have to, and it’s perfectly acceptable not to. ‘You would like the bill?’ is a word-for-word translation of the French equivalent: ‘Vous voudriez l’addition?’

The third problem is the nature of languages themselves, which Wittgenstein’s quotation alludes to more specifically. Languages are a constantly evolving, adapting and changing phenomenon that have come about over many generations. They are essentially mutually agreed sound systems that are attached to specific objects, actions, feelings and so on, but without having any particular correlation to the things that they describe. They tell the story of the people that speak them. They are a way to capture knowledge and pass experiences down through the generations.

We all share one planet, and, although the problems we face may not differ enormously between peoples and cultures, the ways in which we’ve come to talk about them do. Different languages are more or less perceptive about different things, depending on the environments in which they have come to evolve. That is why so many Greek idioms and expressions relate to the sea, as the whole country is essentially built along the shore and has relied on ships for thousands of years. It’s perhaps also a reason why Russian idioms focus so much on mysticism and superstition, as what else could you do in Russia’s long, dark and freezing winters other than stay inside, keeping warm around the stove and telling each other stories?

By never venturing outside the very large and comfortable bubble that is the English language, we never come into contact with the rich knowledge and challenging perspectives that other cultures have come to collect on our shared world. Or if we do, we’ll have to approach it through translation, which as discussed causes problems of its own.

As the world becomes more multilingual and more open, English speakers around the world who cling on to their monolingualism ultimately run the risk of ending up quite isolated. Already we have seen political trends in both the UK and the USA that seem to be going in quite the opposite direction to the rest of the world, towards more isolationism, more protectionism and more exceptionalism. Perhaps, in a world where everyone seems to be able to speak our language but we can’t speak theirs, we just don’t feel special any more.

The point of this book, however, is not to offer political commentary. This book was written to celebrate the endless wealth of languages and multilingualism that we are so lucky to have in this world. With the help of many friends around the world, to whom I am extremely grateful, I have gathered a completely non-exhaustive list of intriguing and entertaining words across twelve different European languages, for which there is no easy English equivalent.

These words are like the ‘Big 5’ of language learning. These are the elephants, the buffalos, the lions and the cheetahs that you’ll come across when learning a new language. But, of course, the joy of going on a once-in-a-lifetime safari trip is not just in seeing those animals up close that you recognise from the picture books. You equally enjoy the scenery, the sunsets, eating by the campfire, and the stars as you look up into the night sky. An immense amount of pleasure and interest can be gathered from the more ordinary parts of learning another language too. There is no greater satisfaction than being able to make yourself understood to someone from a different country. There is no moment more memorable than that first time you make a joke in a foreign language that makes someone laugh.

With the right motivation, suitable expectations and access to the necessary resources, anybody can learn another language at any point in their lives. The aim of this book is to offer an amusing glimpse into the magical world of discovery and the treasures that await those who do.

FRENCH

The UK is separated from France by just a thin stretch of shallow water, which we proudly call the English Channel. The French nonchalantly call it La Manche, or ‘the Sleeve’. At its narrowest point, the Sleeve is only 150ft (45m) deep and only 20 miles (32km) wide, which reminds us just how close to the continent our island is. We call that part the Dover Strait, and the French call it Le Pas-de-Calais, or the ‘Calais Strait’.

Despite the fact that, seemingly, neither side can agree on what to call anything, the histories of the UK and France could hardly be more closely intertwined. For many, the history of modern Britain began when a Frenchman named William the Conqueror (the French call him William II) crossed the Calais Strait in 1066 and – as his name might suggest – quickly conquered the country. He found a land full of people speaking a mixture of Saxon German and Celtic Welsh, and so introduced Norman French into the equation. From this mix, the language we speak today was born: a broadly Germanic structure with heavy influence from Celtic languages and almost half of its words borrowed from French, which we call English.

The English might have been quite happy to throw open their arms to French words that sounded fancier than their existing Germanic stock (such as ‘cordial reception’ instead of ‘hearty welcome’) but it’s perhaps fair to say that back on the continent our Gallic cousins have been less enthusiastic about reciprocating the gesture. Keeping English and other influences as far away as possible from the French language is even an activity that has given people their livelihoods for centuries. The infamous Academie Française, or ‘French Academy’, was established in the seventeenth century to try to keep French ‘pure’, which effectively meant to make sure that everyone else in France started talking like they did in Paris; in recent times it has been leading a ferocious effort to keep Anglicisms off the streets of France.

As an example, French radio stations used to be obliged to play a minimum number of songs in French in addition to English chart songs or risk being taken off the air. That particular law may have been dropped after heavy lobbying in 2016, but among many in France this protectionist and linguistically conservative attitude still remains. The French are as proud of their language as the British are of driving on the wrong side of the road. France’s former president Jacques Chirac even made a point of storming out of summits, press conferences and interviews if journalists asked him questions in English, or even if someone just mentioned the English language in a positive light, all to the tacit approval of the French public.

Yet for all its idiosyncrasies, French is a wonderful language. It is the language of gastronomy, of good wine, of music, of literature and, of course, of love. And as we’re about to see, French is a versatile and attractive tongue that has masterfully captured many of life’s intricate nuances.

DÉPAYSEMENT [noun] /day-pay-z-MON/

Travelling the world is a wonderful thing. Nothing broadens your perspectives and challenges your preconceptions more than seeing how people live in other countries, noticing the differences and similarities between their lives and yours. However, on all long trips there comes a point where the exoticism of being in a foreign place might tip over into frustration. Why are there so many mosquitoes everywhere, and why does everyone look so alarmed they might call an ambulance every time you ask for a spot of milk in your tea?

The French understand the discomfort of being away from home very well, and as a result they have created the perfect word for it. It means homesickness, culture shock, disorientation and a longing to be back among familiar surroundings: dépaysement, which literally means ‘de-country-ment’, or the state of having been removed from where you are from.

FLÂNER [verb] /flah-NAY/

One of the true pleasures, though, of going on holiday to a foreign country is the glorious art of doing nothing. You’re not rushing to get to work, nobody needs to be picked up from school and you don’t have a whole list of things you need to get from town before the shops close. So don’t hurry, don’t stress, just put on a pair of comfy shoes and go for a gentle stroll at a pace so comfortable that you almost feel like you’re sitting down. Sit your eyes out on stalks and let them sweep the horizon, from left to right, up and down, absorbing every detail of every building that you pass, and soak in the atmosphere of the new place that you find yourself in.

In French, this is called flâner. This verb literally means just to wander at a relaxed pace through a city, soaking up the atmosphere. Next time you go to Paris remember there’s no need to pay those extortionate entry fees to museums or queue for hours to go up the Eiffel Tower. Just wander through the quaint little streets and when you get back and people ask you what you did, just tell them that you flâner-ed about.

L’APPEL DU VIDE [noun] /lap-PELL dyoo VEED/

If there’s one thing that unites people all over the world, it’s this. No matter where you go, from Portugal to Bosnia, from Thailand to Chile, you will find people who climb up on to very high surfaces and jump. In places like Porto and Mostar, you’ll find it’s teenagers who climb up on bridges and send their friends to go around asking incredulous tourists to first make a donation before they plunge into the fast-moving river below. In other places, you might find it’s tourists themselves who’ll happily strap themselves to elasticated ropes and throw themselves into the ravine, with blind faith that the rope will hold them. And if that’s not enough, you can even pay someone to take you up several thousand feet into the air on an aeroplane and then leap out, triggering your parachute whenever you’re ready.

Why are we so entranced by this peculiar dance with death? Whatever the reason, the truth is that many of us have a gnawing curiosity about what it would be like to plunge through hundreds of metres of atmosphere and live to tell the tale. The French have a nice term to explain this urge: l’appel du vide, which literally means ‘the call of the void’.

EMPÊCHEMENT [noun] /om-pesh-MON/

The French essentially invented modern-day social life. France’s cities are filled with millions of cafés, brasseries, bistros and restaurants with chequered multicoloured chairs and shiny marble-topped tables. Local people can spend their entire weekends flitting in between these cafés from social engagement to social engagement, drinking a coffee here, a glass of wine there, smoking the odd cigarette under a heater in the winter or reading a couple of pages of whatever book they have to hand.

Every now and then, though, their plans might be interrupted. Suddenly they might find themselves unable to make an engagement with someone that they’d arranged weeks before, because at the last minute something has come up. Maybe a pipe has burst at home, the car won’t start, the trains are on strike, they’ve had an invitation from someone they’d prefer to see instead. Or maybe they just decided that they’d rather spend the day reclined on the couch, reflecting on the meaning of life while gazing through their French windows at passers-by in the street below. Whatever it is, that thing in French is called an empêchement and is a perfectly reasonable way to cancel on someone at the last minute. It literally means a ‘prevention’.

RETROUVAILLES [noun] /ruh-troov-EYE/

The world is getting smaller, but we’re finding more opportunities than ever before to spend more time in different parts of it. Young people, unimpressed by the thought of going straight into working nine to six every day with twenty days’ leave per year, are tending to just pack a rucksack, book a flight somewhere and go off travelling for a few months or years until they’ve worked out what they want to do. People in their late 20s, early 30s and older are coming to the conclusion that life in their home countries isn’t all it’s cracked up to be and are finding there are better chances overseas in places where they might one day actually to be able to afford to buy a house. Pensioners are spending their whole lives saving for that day when they can book a one-way ticket to somewhere sunnier and spend their days reading by the pool and soaking up the vitamin D they’ve always lacked. All of this is like a dream come true for the individual concerned, but inevitably they will carry guilt about those that they’ve left behind. Even with all the technology in the world, when you move away from your friends, family and loved ones to pursue a life overseas, a distance develops between you that becomes increasingly hard to bridge.

Yet it’s all worth it for that truly magical moment when you see each other again. Those reunions at airports, railway stations or wherever you meet that person again after so long are really special. They make the months or years of heartache that precede them disappear. The French language recognises that these are no ordinary meetings. They are bursting with emotion and joy. They are retrouvailles.

PARLER YAOURT [verb] /par-LAY ya-OOR/

It will come as no surprise to anyone from the UK that we don’t exactly have a reputation around the world for being particularly proactive about speaking foreign languages. Many of us have mastered the art of smile-and-point, or can manage impeccably to slow down the pace of our English so that people around the world can understand us. But when it comes to actually speaking the languages, we trail in the wake of our European neighbours such as Sweden, the Netherlands, Greece and Portugal, all of which have populations where more than 50 per cent of people can hold a conversation in at least one other language.

Fortunately, though, we’re not alone. The French are slightly better than us, but not by much. Instead of Britain’s trademark smile-and-point technique, the French have developed a rather marvellous tactic that they deploy to get by wherever they are in the world. Parler yaourt, which literally means ‘to speak yoghurt’, is when you speak another language incredibly badly with lots of mistakes, making up lots of words as you go along, or just saying French words in what sounds like a convincing accent. You can also chanter yaourt, or ‘sing yoghurt’, when you try to sing along to a song you don’t know the words to.

RÂLER [verb] /rah-LAY/

France has bestowed upon the world many great things. Exquisite wines, unbeatable cheeses, world-class gastronomy and lots of existentialist philosophy. The last of these things – existentialism – is a defining feature of modern French life. Those brasseries across Paris will be full of people sipping bitter coffees, loosening their ties and letting off steam to their friends about everything that is wrong or imperfect in life. Why do the shops have to close on a Sunday? Why is the price of rent so high? Why is the government putting up even more taxes or threatening to raise the retirement age by six months?

The French have taken what we know as having a bit of a moan and turned it into an art. The French can complain about the world more beautifully and more persuasively than almost any other country on Earth. As this developed, the word ‘complain’ no longer held any gravitas in the face of this magnificent onslaught of doubts. The French language therefore provided a new word that fit it much better: râler, ‘to let off steam and criticise the world’.

CARTONNER [verb] /car-tonn-AY/

Sometimes things are so successful that they take the world by storm. In France, the hazelnut chocolate spread known as Nutella (which, incidentally, is Italian) has become such an integral part of French life that in January 2018 there were riots in one of France’s leading supermarkets because it was offering an exceptionally generous discount on large tubs of it, which led customers to fight each other in the queues to get their hands on it.

That might remind you of the similarly rather ugly scenes on Oxford Street in 2007 when Primark’s first superstore opened and shoppers broke the all holy British tradition of orderly queuing by punching each other to be the first in line to get all the best deals.

These brands are real successes, and French rewards such successes with a special verb: cartonner. This means ‘to cardboard’ and refers to when you hit the cardboard target square on at a shooting range. If we were to translate this idiomatically, perhaps in English we’d say: ‘to bullseye’.

JE NE SAIS QUOI [noun] /zhuh nuh say KWAH/

Our experience of the world is inherently limited by our ability to express our thoughts, feelings and reactions with language. All languages are inherently limited, as they tend to capture the experience of a certain group of people or culture in the world. That, of course, is fine, because we can invent new words and see if they catch on, or borrow words from other languages that seem to make sense.

The French language, to its credit, at least recognises its own limitations. When French speakers reach that abyss of running out of words to express why they like something, they can stealthily dodge the more pernickety questions that arise by simply saying that they like it because it has a certain