Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

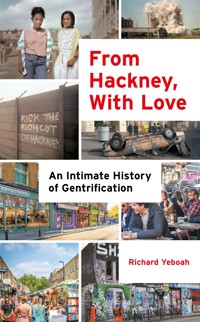

For so many decades, Hackney was the pinnacle of the dynamic multicultural spirit of modern Britain, demonstrated by the borough's vibrant and energetic streets and often controversial political, cultural and socio-economic character. But today, the Hackney that long-standing residents once treasured seems to be disappearing. The borough's diverse working-class communities – who survived the run-down council estates, the overwhelming deprivation and the postcode wars – are increasingly being pushed out by the middle classes who buy up their homes, rename their shops and reshape their neighbourhoods. How did Hackney go from being one of the poorest and most uninviting places in the country to being one of the most sought-after locations? In these pages, lifelong resident Richard Yeboah uncovers the borough's lively history, revealing the uncomfortable story of how gentrification has transformed Hackney, for better or for worse. Examining some of the most contested issues facing the borough today – including housing and regeneration, politics, class, race, education, youth violence, culture and gender identity – Yeboah amplifies the voices of Hackney's new, existing and former communities and explores the relationship between gentrification and feelings of belonging and loss. From Hackney, With Love is both a unique love letter to one of the most vibrant parts of London and a warning that its very existence is in jeopardy.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 301

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

“FromHackney,WithLoveis a wonderful book about gentrification written by a long-time, working-class, Black Londoner – not another academic or gentrifier (and they are often both)! It’s a superb account of the policies and practices that have turned a once affordable, multicultural, gritty London borough into a soulless playground for wealthier groups. It’s also a painful comment on both the slow violence of sociocultural displacement and Richard Yeboah’s own recognition of his likely physical displacement. His book is a provocative outing of what he calls ‘structural adjustment’ and of educational disinvestment and subsequent ‘academisation’, both of which forefront the role of the local and national state in Hackney’s gentrification.”

Loretta Lees, scholar-activist on gentrification and former chair of the London Housing Panel

“Hackney has long been a laboratory for testing conflicting theories of inner-city success and failure, owing to its long history of industrialisation (and subsequent decline), mixed housing stock, intricate patterns of migration and tradition of radical municipal politics. Richard Yeboah is ideally placed to tell this story afresh, having been born in the borough, where he still lives, and does so convincingly. FromHackney,WithLovecombines personal testimony with an impressive reading of the wide-ranging academic research that underpins Yeboah’s persuasive chronicle of the contested theory of contemporary inner-city gentrification.”

Ken Worpole, writer and social historian

ii“Anyone interested in understanding what gentrification means to multi-ethnic working-class communities in London should read Richard Yeboah’s remarkable book, FromHackney,WithLove:AnIntimateHistoryofGentrification.”

Paul Watt, visiting professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science and author of Estate Regeneration and Its Discontents: Public Housing, Place andInequality in London

“Richard Yeboah is in the right place at the right time to witness and record with such impeccable attention to detail and tenderness the recent trajectory of Hackney. This book is a compelling mosaic of autobiography, class inquiry and civic history of one of London’s most progressive and influential boroughs – charting its development from post-war rebuilding to industrial decline to regeneration and ascendancy to current hipness and middle-class desirability. Even though the borough is ‘safer’ and ‘nicer’ today, have these benefits come at the cost of eroding the sense of community and in the process Yeboah’s memories? From Hackney, With Love covers the anguish of recognising love of place in the face of relentless evolution and expansion and the eradication of established working-class structures that kept people in Hackney unified and safe. Yeboah’s work is a monumental achievement and much-needed study at this moment in time, as we question the future value of tradition, customs and culture. I wish I had had this book as a resource and reference when I started out photographing Hackney in the mid-1980s, and it has put so many of my subconscious thoughts into such a beautiful shape. Wonderful.”

Chris Dorley-Brown, documentary photographer and filmmaker

iii“From Hackney, With Love succeeds admirably in its mission to deliver an intimate portrait of a community struggling with immense change against the backdrop of a compelling political economic history that helps us understand the drivers of gentrification as well as its deeply personal effects.”

Leslie Kern, author of Feminist City and Gentrification Is Inevitable and Other Lies

“A compelling combination of autobiographical poignancy mixed with illuminating well-researched facts; this book is a total triumph. This enthralling deep dive is a must-read for anyone – whether from Hackney or not – interested in the ever-changing social fabric of inner-city life and its impact on the inhabitants living within the areas most affected by the ever-tightening grip of gentrification. I will return to this brilliant book again and again and again.”

Ashley Hickson-Lovence, author of The 392, Wild East and Your Show

“From Hackney, With Love artfully blends autobiography with analysis, providing both a deeply personal and a passionately political history of Hackney’s gentrification. There are few more contentious issues facing modern cities than gentrification, and there aren’t many – if any – places in which the gentrifying process is more divisive than it is in Hackney. Neither a lecture nor a rant, From Hackney, With Love guides the reader through the contours of this controversy with gentle tenacity, careful balance and a lot of heart. However familiar or unfamiliar readers are with Hackney and with gentrification, they will learn a lot from this excellent book.”

Luke Billingham, author and youth worker at Hackney Questiv

v

vi

From Hackney, With Love

An Intimate History of Gentrification

Richard Yeboah

Contents

Foreword

Despite leaving Hackney for Norwich in 2018, the borough is, and always will be, my home.

I was born in Homerton Hospital in 1991 and spent the first few months of my life in Boscobel House just off Graham Road in Hackney Central. Then my family moved to Hoxton, following a short intermediary stint in Palmers Green (London Borough of Enfield), when I was three.

I moved out for good in my twenties, but my mum is still there, clinging on in Clinger Court, as the landscape around her continues to change with disorientating rapidity. A newly redeveloped leisure centre (Britannia), a new secondary school (City of London Academy) and new high-rise apartments (Shoreditch Parkside) have all sprung up in recent years, making the area that I grew up in around Shoreditch Park pretty much unrecognisable from what it used to look like when I was younger. Now the little estate I used to call home is practically overlooked by these soaring, xnondescript, shiny new high-rises that literally block out the sunlight that previously used to pour onto the bricks of my old block.

Every time I go back to see mumsy now or hang out with my younger brother, it amazes me justhow much the area continues to change. The formative forecourt of Hoxton where I made friends, lost friends, experienced unrequited character-building teenage crushes and turned from a boy into a man basically is not that same stomping ground I used to totter down in the 1990s and 2000s like a young Richard Ashcroft in that ‘Bitter Sweet Symphony’ video.

I knew as I soon started writing properly, in my early twenties, I wanted to in some way creatively explore this ever-continuing transformation. Put Hackney at the centre. Make Hackney a character almost. Examine just how much the area has changed down the years and begin to unpick and unpack the subsequent identity crisis the borough suffered, and arguably still suffers from, following the regular and rapid redevelopment.

One of the first short stories I ever wrote was for a university module and was based on an anecdote my mum told me some years ago, involving a trip to a new coffee shop that had opened at the top of Hoxton Street. Not long after it opened, and after a long day at work as a carer, my mum decided to pop in and see what this new place was like. She strolled in and asked for ‘a coffee please’. The moustached man behind the counter looked perplexed. What kind of coffee? Oat milk latte? An extra hot macchiato? xiA double-shot espresso? There was a dizzying plethora of options. ‘Just a coffee,’ my mum reaffirmed. ‘Two sugars,’ she added. She would have been happy with two generous heaps of Nescafé and a splash of full-fat milk, but the baffled barista, clearly not yet familiar with the existing clientele of the area, did eventually muster something up. Sadly for my mum, though, the fancy coffee she didn’t really want, couldn’t pronounce and actually didn’t much like had cost her nearly £5. She never went back again.

This little story in many ways epitomises what has happened to Hackney in recent years: long-serving residents slowly being priced out of the area they have spent much of their life in. First, it’s the coffee, then it’s the bars and pubs, then, most worryingly, it’s the housing that gets increasingly too expensive to rent, let alone dream of buying and owning outright. I was frustrated, intrigued, worried by this ever-present conundrum and the resulting ambivalence led me to start writing my debut novel, The392– a book set over just thirty-six minutes almost entirely on a fictional bus route that weaves its way through the backstreets of Hackney, picking up passengers from all walks of life. The rich, the poor, the young, the old, the home-owning and the homeless all board this little single-decker bus bound for neighbouring Islington while a suspicious-looking man loiters at the front of the bus shouldering a questionably heavy rucksack. Although the route is entirely made up, in writing The392, I used lived experience, real streets, real parks and real landmarks to make the book feel as authentic xiias possible. I wanted to do all I could to immortalise the area I loved and that essentially shaped everything about the person I am today. At its core, it’s a book about people and places and love for the area that makes and shapes you, whoever you are, wherever you’re from.

Even though I moved out some time ago, I’m still incredibly possessive over my home borough. At the start line of every Hackney Half Marathon I travel down to do, I nearly always have this bubbling belligerent urge to shout at the other runners who have schlepped it from other boroughs (and counties and countries sometimes!), Watchyourstep, thisismypatch,Iwasbornhere!But through writing – my own book and brilliant books like this – we can see what Hackney is like now and we can examine, explore and, most pertinently, remember how it used to be.

Because whether you’re from Hackney or not, the borough is rightly regarded as a unique and special place, full of character and characters, that has had a long-lasting impact on British culture. I’m talking Mary Wollstonecraft, Hackney Marshes, the Kray Twins, Top Boy, Idris Elba, Visions Video Bar and Unknown T – the list goes on and on. There’s history to the borough, rhythm and musicality too, an all-consuming almost indescribable abstract energy that you feel palpably as soon as you step off the Windrush Line. You still have to watch your step, yes. You still have to be streetwise, of course. The area is changing and changing and it’s getting harder to find clues of what Hackney used to be like, that goes without saying, but at the end of the day, I xiiican confirm unequivocally that there always is, and always will be, love.

Richard Yeboah’s FromHackney,WithLoveis a compelling combination of autobiographical poignancy mixed with illuminating well-researched facts; this book is a total triumph. This enthralling deep dive is a must-read for anyone – whether from Hackney or not – interested in the ever-changing social fabric of inner-city life and its impact on the inhabitants living within the areas most affected by the ever-tightening grip of gentrification. I will return to this brilliant book again and again and again.

AshleyHickson-Lovence

March2025xiv

Introduction

It was the summer of 2020 – a summer like no other for most of us who lived in Hackney. The past few months had been spent in lockdown confined to my living room due to the Covid-19 pandemic, with daytime television on in the background as I sat through constant Zoom calls while I worked from home in between teaching my son about the various subjects in the school curriculum. Schools, parks, restaurants and non-essential shops had all been closed since March, as we entered a new, dystopian existence where we all feared for our future as the pandemic took hold of everything around us. It was a time of both reflection and contemplation, as our once busy lives all of a sudden came to a standstill and we were all forced to stay home. But the pandemic also brought a deep sense of isolation as the streets outside fell silent, with the once lively working-class community in our estate in Stamford Hill all but disappearing during lockdown. I hadn’t realised how xvimuch I would miss the noise of kids playing basketball in the cage late at night, people blaring hip hop and dancehall from their kitchen windows or my daily conversations on the estate with my neighbours about how great or shit their day was. The pandemic had not only stripped the soul out of our estate – it had also stripped the soul out of the once vibrant and energetic streets of Hackney.

Hackney is where I was born and the place I have called home for the past thirty years, but I don’t think I ever fully acknowledged the very personal and psychological impact of the borough on my well-being, my identity and, fundamentally, my existence until the pandemic. Hackney is the place where I went to nursery, primary school, secondary school and college. Hackney is the place where I was baptised and had my Holy Communion, the place where I met my wife and my closest friends and the place where my parents bought their first home. It is where my siblings and I grew up, where I learned to ride a bike and drive a car, and where I eventually started my own family. Hackney is the place where I am writing this book. Hackney has fundamentally defined who I am today and has defined so many of my friends and family, who, despite Hackney’s sketchy reputation in the past and the many shortcomings throughout the borough’s long history, still have a deep devotion to the area. In fact, so many of us from a range of different ethnicities, age groups and backgrounds who have experienced life in Hackney over the decades have reaffirmed a xviiprofound intimacy and connection with the borough that reflects both the good and the bad of the area.

But the irrepressible energy and culture of the Hackney that had shaped my entire life had suddenly disappeared during the pandemic. I felt a little lost. As soon as the government eased Covid-19 restrictions that summer, I bought a banged-up second-hand bike from Haggerston with the sole purpose of cycling around Hackney to reimmerse myself once again with the neighbourhood and the communities of Hackney, with my first visit being to my former home in Church Crescent, just off Well Street. After cycling around my old area in South Hackney, I soon realised that a large part of my perception of Hackney was a figment of my memory, persisting stubbornly against the shock of the pandemic but also deep-rooted in my yearning for the Hackney that I grew up in. What happened to the large green space where I used to play with my friends off Kingshold Road? It was now a new housing apartment. And since when was the old dry cleaners on Well Street, opposite the This ’N’ That shop, a fancy pizza parlour? Cycling through unrecognisable shopfronts, rebranded cultural hotspots and unfamiliar infill housing developments that sat alongside so many of the estates that my friends and I used to walk and run through made me feel uncomfortable – and that’s without mentioning the changes in the people. The pandemic alone wasn’t responsible for the soullessness of daily life in Hackney in 2020. It was also because of gentrification.xviii

The Hackney that I believed would re-emerge postlockdown had actually been fading away long before the pandemic, and although deep down I knew this had been the case for the past couple of years, I had struggled to appreciate the slow yet symbolic demise of our borough. The gentrification of Hackney had happened right before my eyes, much faster than I had appreciated. The Hackney that I once knew and loved had vanished, and if it weren’t for the pandemic, I may never have taken the opportunity to mourn the loss of my home. But it’s not just Well Street. It’s Dalston, Clapton, Hackney Wick and Manor House. It’s Homerton, Stoke Newington, De Beauvoir and London Fields. Gentrification is sweeping through our homes and neighbourhoods, our schools, our favourite places and our communities – and it appears there is nothing we can do about it. For so many decades, Hackney was the pinnacle of the dynamic multicultural spirit of modern Britain, demonstrated by the borough’s infamous and often controversial political, sociocultural and economic character. But today, the Hackney that our communities once loved and treasured for so many years appears to be disappearing right in front of us, along with its remarkable and pervasive history that has become so synonymous with the area and its people over the past few decades.

Once considered the ‘worst place to live’ in the UK, according to a 2006 study by Channel 4, for most of its recent history, Hackney was often described as a modern-day slum, riddled by dilapidated housing, poor performing schools, xixhigh levels of crime and overwhelming levels of poverty.1 But it was ourHackney, and we collectively acknowledged that Hackney’s poverty was normal. In fact, we lived and breathed Hackney’s poverty, normalising the conditions of deprivation that had existed for decades prior, and shaped our experiences around decaying homes, unclean streets and questionable neighbours with even more questionable motives. Hackney built friendships, built relationships and built families, underpinned by the ‘stiff upper lip’ of our communities against the adversity and hardship felt by so many in the area and the wider East End in the past. Despite the problems of poor housing, social disorder and widespread poverty, I will forever have fond memories of living and growing up in Hackney – and so do so many other former and existing residents.

I still remember the football matches with my friends in the car parks and losing our barely pumped balls in the neighbour’s garden or haggling one pound from your mother as your friends chased the ice cream van down the road. Yet these memories are synonymous with the fear of being assaulted on the stairwell at night or being burgled in your own home, and the eerie sounds of dogs and police sirens shouting strange loud noises until dawn. To live and survive in Hackney meant we were armoured with immense pride, self-admiration and individual perseverance in the face of deep, structural inequalities. In fact, this perseverance matters so much more in the face of the gentrification of Hackney, as our communities fight to preserve, protect xxand hold on to our livelihoods in the borough. The Covid-19 pandemic had simply intensified my abstract sense of mourning for the Hackney of old, but it had probably been brewing for years in the back of my mind as a result of the impact of gentrification.

I remember having a conversation with Paul, a former resident who grew up on the Pembury Estate in the northeast of the borough during the 1970s and 1980s, about the changes in Hackney during that summer in 2020. Less than two minutes into our conversation, Paul remarked: ‘Why are there so many yuppies in Dalston? Dalston used to be an absolute shithole. No one wanted to go there in the day, let alone at night.’ I laughed and nodded in agreement. But then it dawned on me that almost everyone I had spoken to over the past few years about living in Hackney was always so quick to talk about Dalston. So quick to talk about how Dalston had changed after being an ‘unappealing dump’ back in the day and why all of a sudden it was a hipster hotspot and full of middle-class people. I then realised that it wasn’t just me who had apprehensions about the effects of gentrification in Hackney but so many other former and existing residents. However, although most of us would agree that Dalston’s transformation is because of gentrification, we sometimes struggle to articulate what gentrification actually means and whyit has affected Hackney. I’ll try to give an explanation.

Put in simple terms, gentrification is about the systematic displacement and replacement of poorer communities xxiin economically distressed and deprived urban areas by an influx of wealthier and more affluent people, raising property prices often out of the reach of existing residents. Gentrification isn’t a new concept. It was first coined in the 1960s by sociologist Ruth Glass in her study of the ‘invasion’ and displacement of working-class communities in London by the ‘gentry’ middle classes who used their wealth and capital to upgrade housing in previously poor areas for their benefit, fundamentally shifting the social character of locations like Hampstead, Islington and Paddington.2 Notably, Glass stated at the time that London’s East End had been exempt from gentrification, but fast-forward fifty years and gentrifier communities have swept through Hackney and other parts of the East End, as well as areas like Brixton, Peckham, Camden and Tottenham, as poor, multicultural working-class communities are increasingly being pushed out by the middle classes who buy our homes, rename our shops and reshape our neighbourhoods. In fact, gentrification is taking place in major cities in other parts of Britain and across the world, such as the Northern Quarter in Manchester, Stokes Croft in Bristol, Digbeth in Birmingham, Brooklyn in New York City, the Bay Area in San Francisco, Prenzlauer Berg in Berlin and Faubourg Saint-Denis in Paris, with historically poor inner-city communities being uprooted by a new, wealthier class of people who are now seizing upon and growing a fascination towards previously ‘unfashionable’ areas.

The emergence of gentrification in Hackney and in other xxiimajor cities across the ‘Global North’ mainly lies in the deindustrialisation and decline of manufacturing industries in the inner city during the 1970s and 1980s. Deindustrialisation was hugely damaging for areas like Hackney because it caused mass unemployment and deprivation across working-class communities, with many industries being moved to the ‘Global South’ due to cheap labour (and lower standards) as a result of globalisation or being automated altogether by improvements in technology. In its place, post-industrial financial, business and creative services began to emerge in major cities by the end of the twentieth century – particularly following the emergence of the internet – attracting a new, wealthier, white-collar professional and managerial class to live and work in previously poor inner-city areas. For the most part, this new urban ‘elite’ have growingly established themselves in the inner city, gradually ‘phasing out’ working-class communities by flexing their financial wealth and wielding their class supremacy to influence the value of housing and cultural spaces, mould the direction of government policy and reshape urban areas altogether for their benefit.

The recent changes in Hackney over the past several decades are probably some of the clearest examples of gentrification in full force. Throughout the late 1970s and 1980s, Hackney saw so many of its long-standing factories and industrial businesses, such as the Lesney Matchbox toy factory and the London Lane shoe factory, which had their roots in the East End Jewish community, closing down as a xxiiiresult of economic recession and globalisation. This left so many of the borough’s residents without a job and coupled with the administrative challenges within Hackney Council at the time and the lack of investment in the area’s housing stock, Hackney became overwhelmingly poor. However, the development of Canary Wharf in the late 1980s in neighbouring Tower Hamlets, estate regeneration and the rise of tech start-ups and creative agencies on the edge of the City of London in Shoreditch made Hackney increasingly attractive to a new urban ‘elite’, who would gradually move into the area during the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s due to the cheap availability of housing and relatively low rents. But Hackney’s gentrification hit hardest once the 2012 Olympics was announced in 2005, because it started an investment boom in the borough as property developers and investors flocked to seize control of Hackney’s landscape due to its proximity to the Olympic Village. This encouraged even more people from the new urban ‘elite’ to live in Hackney and intensified the price and demand for housing and land across the borough. The welcome mat was rolled out for gentrification.

But what have been the effects of the gentrification of Hackney? In the space of three decades, Hackney went from being one of the poorest and most uninviting places in the country to being one of the most sought-after and desired places to live and work in the UK. The connotations in the past of Hackney being ‘hell on earth’, as mentioned by Jane, a friend of mine from Stamford Hill, appear to be xxiva distant memory. Now Hackney is full of lavish new builds like the houses on the corner of Dalston, trendy businesses in Church Street and market stalls in Chatsworth Road, and it has some of the highest house prices in the country – with some properties on the market for way over £1 million. But don’t forget about the impact on us: the long-standing residents who survived the run-down council estates, the media frenzy of ‘Murder Mile’ and the postcode wars, the below-par schools and the overwhelming deprivation across the borough, only to be pushed out and alienated by a new version of Hackney that no longer feels like home.

And don’t forget about Hackney’s cultural and political history. It is the place where Britain’s first Black female MP Diane Abbott was elected, where political activist Angela Davis gave a landmark speech at Hackney Town Hall in 1986 and where former Prime Minister Tony Blair once lived in the 1980s. Furthermore, Hackney has a famous and renowned history of multiculturalism underpinned by the area’s resistance to racism, fascism and discrimination, as well as the promotion of workers’ rights and gender equality that has helped to shape the culture and experiences of its communities. Just take a short walk down Dalston Lane and you’ll see the colourfulness of Hackney’s multiculturalism in visual form through the Hackney Peace Mural, which was designed by Ray Walker over forty years ago and remains one of London’s most famous outdoor works of art. In fact, in 2006, sportswear giant Nike tried to take advantage of Hackney’s cultural legacy by producing a new xxvrange of clothing with the borough’s name and Hackney Council’s logo – albeit it was eventually sued by the council for copyright infringement and settled out of court.3

But Hackney’s famed multiculturalism is also reflected in the people who have emanated from Hackney who have contributed so much to Britain and the world more widely. Hackney is the birthplace of businessman Lord Alan Sugar, award-winning actor and DJ Idris Elba (whose show In theLongRunis based on his own experiences of growing up in the borough), crime kingpins the Kray Twins, actress Barbara Windsor, photographer Dennis Morris (who was renowned for his photos of Bob Marley and The Wailers in the 1970s) and has been home to so many other celebrated people. Moreover, the Four Aces Club in Dalston was one of the first venues to play Black music in the UK and became a hub for newly arrived West Indians and eventually a hangout for icons like Bob Dylan and Mick Jagger; the Hackney Empire has been the host of so many famous actors over the last century; and in popular culture, the fictional Summerhouse Estate in the widely acclaimed series TopBoyis based in Hackney. Hackney’s political and cultural influence is massive and remains integral to the legacy of the borough.

However, the recent gentrification of Hackney has changed the complexion of our neighbourhood and communities, transforming our cultural identity in the process and ushering in a growing reimagination of what it means to be from Hackney. The imagery of a borough bound by xxvian amalgamation of working-class values, multiculturalism and cockney pride that has long existed in my memory is being besieged by an often white, middle-class and disconnected community and local landscape that are increasingly overriding Hackney’s famous history. Both of these versions of Hackney exist in my mind simultaneously, but day by day, this ‘new version’ of Hackney eats away at my treasured memories of my home as I form new ones, surrounded by fancy and shiny apartments, trendy shops and even trendier ‘hipster’ communities. This is why now is the time to surface my own and other personal reflections and experiences of gentrification in Hackney and reveal the polarising effect it has had on communities across the borough, like in so many other inner-city areas across Britain and the world.

This book will not only tell the controversial and uncomfortable story of how gentrification has transformed Hackney over the past few decades; it will also delve deep into the lives and experiences of the very communities involved and affected by urban and social change in the borough, explored through some of the most contested issues facing Hackney today, including housing and regeneration, politics, class, race, education, youth violence, culture and gender identity. The aim is to amplify the voices of Hackney’s new, existing and former communities and explicate the relationship between gentrification and feelings of belonging amidst the growing sense of loss of long-standing communities. By sharing my story and the story of so many xxviiother people across the borough, From Hackney, With Loveis an evocative tribute to Hackney’s communities and a call for the gentrifier communities to appreciate and acknowledge the very deep and divisive legacy of gentrification on the urban environment within Hackney. I hope that this book will help other marginalised communities in different parts of London, Britain and the world interpret and juxtapose their own lived realities and apprehensions about gentrification.xxviii

NOTES

1 ‘Is Hackney really the worst place to live?’, The Guardian, 26 October 2006, https://www.theguardian.com/news/blog/2006/oct/26/ishackneyreal

2 Ruth Glass and University College, London, Centre for Urban Studies, London:Aspects of Change (London: MacGibbon & Kee, 1964), pp. 18–19.

3 ‘Hackney wins logo case against Nike’, The Guardian, 11 September 2006, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2006/sep/11/politics.money

Chapter One

Council Estate of Mind

It was the early 1950s. The post-war period had begun. After years of fighting, Britain had emerged victorious from the Second World War and sweeping social reforms had been introduced by Clement Attlee’s Labour government. But Hackney, like so many other working-class areas in Britain, was still suffering from the physical, socio-economic and psychological effects of the conflict and the Nazis’ bombing campaigns during the Blitz. Many people across Hackney had lost loved ones, jobs and their homes because of the war, with over 5,000 homes, as well as other buildings, shops and factories, being destroyed by the Luftwaffe’s bombs.1 Many people were now homeless. David, a former resident of Homerton, remembered how hard life was in Hackney as a child in the 1950s after the destruction: ‘Things were hard back then. We were still rationing food, and my home, in fact my whole street, had been bombed. It was like a warzone but without the soldiers or the flying 2bombs.’ The war had caused a severe shortage of housing and made the construction of new homes in Hackney an urgent priority, particularly for the war-torn working-class communities, many of whom had lived through poverty prior to the war, and a growing immigrant population from across the Commonwealth and beyond who arrived in Britain to help rebuild the country after the conflict. Of course, gentrification wasn’t a problem in Hackney way back in the 1950s. But the decade is an important starting point in explaining both how and why gentrification would eventually become such a divisive issue in the borough decades later. And that starting point revolves around the building of new social housing for Hackney’s communities in the aftermath of the Second World War.

The end of the war would bring forward a new era for social housing not only in Hackney but across Britain. Spearheaded by the ‘post-war consensus’ that nationalised major industries, introduced the National Health Service and created the welfare state with the aim of taking care of the British people ‘from the cradle to the grave’, successive Labour and Conservative governments would provide huge investment to local councils to build new homes throughout the 1950s. And Hackney would reap the rewards of the government’s investment in social housing and the area would see thousands of permanent homes and temporary prefabs being built for people waiting to be rehoused after the conflict. New housing estates like the Beckers Estate near Hackney Downs, the Colville Estate in Hoxton and the originalWoodberry 3Down Estate were all built during the decade. These estates were initially seen as a massive success, with improvements in housing quality and design, including underfloor heating, community halls and facilities, storage spaces for bikes and prams and individual balconies.

And that’s probably why so many people in Hackney initially fell in love with their new council estates in the first few years after the Second World War. The new estates had cleared some of the slum conditions and the poorly constructed homes that had been built during the Victorian era and the homes that had been damaged during the Blitz. For many residents, it was the first time that they had their own bedrooms and their own gardens, let alone their own homes. I remember speaking to Harry, a former resident of Hackney who moved to the Pembury Estate in the early 1960s during his teenage years. Harry recalled initially sharing a bedroom with his father, mother and five siblings as a child in shared accommodation in Stoke Newington, with other extended family members living in the room next door… with everyone sharing sanitary facilities. ‘Pembury was like a palace when I moved in,’ Harry proclaimed during our conversation in 2021, demonstrating the great pride he had for his new home. Patrick, who moved into the Kingsgate Estate after it was completed in 1961, also recalled how great it was to move into his new home: ‘I loved it! There was a big central play area, a laundrette and a hall for social events. The estate was well looked after and we all felt like a community.’

4But by the early 1960s, things began to change for Hackney’s new council estates, with major flaws beginning to emerge that would later have a decisive impact on the eventual decline of council housing in Hackney. Political pressures at a national level towards the end of the 1950s were placing financial restraints on local authorities’ building programmes, and as a result, government ministers were encouraging local authorities to reduce their housing quality standards. This went alongside calls to build more council homes to meet the demand for housing and the government’s mandate of 300,000 homes per year, with less of a focus on renovating existing properties and more of a focus on incentivising ‘building higher’, with the government providing large subsidies to local authorities which built housing above four storeys. By the early 1960s, these policies coincided with the increasing popularity of new construction methods, with city planners and architects favouring high-rise buildings and industrialised ‘large panel system’ building techniques, which were thought to cut completion times, were cheaper to build and would likely ease housing waiting lists. The large, ‘brutalist’ concrete and repetitive design that used prefabricated concrete panels to construct walls, floors and roofs would become a common feature of council estates not only across Hackney but throughout Britain.

Until that point, most of Hackney’s new council estates had been relatively low in stature. But building ‘highrise’ housing would gradually be accepted as inevitable to 5