Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

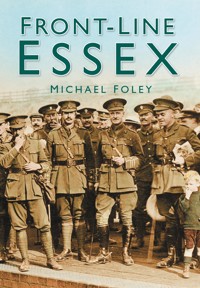

Before the First World War, Essex was a very different county from that which we know today. The economy was largely based on agriculture, and the people rarely travelled beyond its borders, or even out of their towns or villages. The war opened up a whole new world for the people of Essex. Men from the county enlisted in Kitchener's Army and travelled abroad, and many troops came into the camps and barracks which sprang up. Some of these were men from across the empire who came to fight for the mother country. Essex was a key area during the war: situated on the east coast, it was thought that the enemy could potentially use it as a site for invasion, so many defences were set up all round the county. Essex was subjected to great danger and harsh times by the enemy in the form of air raids from Zeppelins, and later, from aeroplanes. This book sets out the experiences of the county against what was happening in the broader theatre of war.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 136

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2005

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

FRONT-LINE

ESSEX

MICHAEL FOLEY

To Anne, for understanding during the many hours spent writing this book.

First published in 2005 by Sutton Publishing Limited

Reprinted 2007

Reprinted in 2010 by

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Reprinted 2011

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Michael Foley, 2011, 2013

The right of Michael Foley to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5254 5

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1.

The Napoleonic Years to the First World War

2.

The First World War to the Second World War

3.

The Second World War to the Present Day

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

All illustrations are from the author’s private collection.

Although every attempt has been made to find the copyright owners of all the illustrations, anyone whose copyright has been unintentionally breached should contact the author through the publisher.

Introduction

Essex has always been one of the most heavily defended counties in Britain. From the earliest recorded battles in the county, when Boudicca burned the Roman town of Colchester, the men of Essex have been joined by others from all over the country when defence of the realm has been necessary. In order to stop the invasions of the Spanish, the Dutch, the French under Napoleon and the Germans in two world wars, the county became what was essentially an armed camp. This led to the building of defensive positions that have, in some cases, evolved over a period of 500 years or more to meet the changes in weaponry that have taken place. Along with the development of these fortified posts, barracks for the troops have been constructed. Before the Napoleonic period, the men lived in temporary tented camps.

Colchester, for instance, is one of the oldest garrison towns in Britain, and it has been supported by a number of less well-known establishments.

When I first became interested in the history of the military in Essex I was surprised to find that information on the many military sites in the county was quite scarce, and there were a number of sites unknown to me – perhaps because many of the books about individual barracks are either out of print or very difficult to obtain.

I have therefore done my best to include information on the main military sites that have existed in Essex and how they have evolved through the years. I hope this will provide a useful overview for those like myself who were unaware of how much influence the armed forces have had on the development of the county.

The sites, towns and military bases covered in Front-Line Essex.

ONE

The Napoleonic Yearsto the First World War

The end of the eighteenth century saw the beginning of the wars that followed the French Revolution and the rise to power of Napoleon Bonaparte. The wars led to a great deal of change in the military presence in Essex. For instance, until this time large summer camps had been sited around the county as gathering places for the regular army and the militia, with many of the men also being billeted in private houses and inns. Policy changed and barracks started to appear, turning many Essex towns into temporary garrisons.

CHELMSFORD

Although an ancient town with origins stretching back as far as the Roman period, Chelmsford retained its small-town appearance until the mid-nineteenth century. It was only the opening of the River Chelmer in 1797 to allow navigation from the River Blackwater and then the coming of the railway in 1843 that led to an increase in the size of the town. Chelmsford’s main connection with the military was during the Napoleonic Wars, although the 32nd Foot had been stationed there in 1748.

As with other towns between London and the coast, Chelmsford was used to seeing army units marching through its streets en route for sea ports and Europe well before it had its own barracks. Of course, many of the soldiers that passed through the town were billeted on local homes or inns for short periods, and there were often complaints about the amount paid for these billets – only 5d a day for an infantryman; a horse was more expensive at 6d. There were over 8,000 soldiers billeted in Chelmsford and the surrounding area by 1794, mainly in its twenty-eight inns. To put this in context, the civilian population at this time was only just over 5,000. During the summer the troops moved to camps, such as those at Warley, but by 1795 Chelmsford had its own barracks.

Although the new barracks solved some of the problems of billeting it also raised others. For example, there was disagreement between those in control of Chelmsford and those in Moulsham over who would meet the cost of upgrading the road leading to the barracks in Moulsham. In the end Chelmsford council had to contribute to the costs. The road was built and became known as Barracks Lane. Another problem was the groups of camp followers who set up home around the barracks, often in small huts.

In 1796 more barracks were built at the opposite end of the town, which helped to alleviate the overcrowding the soldiers in the first barracks had suffered. With the number of soldiers now living in the two barracks, the population of the town was again doubled.

The presence of so many soldiers caused problems, however. In 1803 there was a War Office enquiry after it was reported that soldiers were going out at night and committing robbery. The enquiry found that officers at the barracks had tried to cover up for the guilty men, and consequently, some of them were forced to leave. Eventually the only regiment left at the barracks was also forced out, leaving them empty until the outbreak of hostilities again in 1803, when they filled up once more. There was also a resumption of the practice of billeting men in inns and private houses in the town. The rates for housing a soldier had been raised since the first conflict, and many innkeepers, especially those with stables, made a good profit.

When a group of seventy Germans were billeted for one night in the stables of the Spotted Dog in Back Street in 1804, it was worth more than seventy shillings to the owner. Unfortunately the stables caught fire and thirteen men died.

The government seemed to be taking invasion threats more seriously this time and built lines of defences, including forts, that protected roads in the Chelmsford area. They stretched from the old barracks to the top of Galleywood Common and were about a mile and a half in length. One of the forts was star shaped and was armed with 48lb cannon that covered the London Road. The defences were backed up by 8,000 to 10,000 soldiers in local camps. The construction work was done by soldiers from the barracks, including members of the Lancaster Militia. Part of these defences were in the grounds of Moulsham Hall, which was owned by the Mildmay family.

As well as barracks in the town, there were camps during the summer months close by at both Danbury and Galleywood. The Galleywood area was also the site of the racecourse at Chelmsford. The course had royal patronage after George III gave 100 guineas for a race called the Queen’s Shield that continued to be run until 1887. In its heyday cockfights and prize fighting contests were also held on the common.

The British victory at Waterloo in 1815 ended the war and the defences were removed, but the old barracks were not demolished until 1823. They left behind them a collection of huts still populated by camp followers in what had become a very rough area of the town.

COALHOUSE FORT

The origins of the fort in East Tilbury stretch back to one of Henry VIII’s blockhouses. It was built at Coalhouse Point roughly half a mile from the fort and contained fifteen cannon. Although the armaments were increased a few years later, the blockhouse then fell into disuse. Part of the sea wall was removed and this led to flooding. The site was still derelict when the Dutch attacked the area in the seventeenth century and damaged the nearby church tower.

The wall of Coalhouse Fort facing the Thames, 2004.

The inside of Coalhouse Fort. The rails were used to carry heavy equipment.

When the French wars broke out at the end of the eighteenth century, the area was rearmed and a 24-gun battery was constructed close to the present site of Coalhouse Fort. Its battery also had barracks for the garrison. It was again disarmed after the war and it was another forty years before the battery was rearmed with more and larger guns.

The present Coalhouse Fort was part of a triangle of three new forts, two of which were in Kent at Shornemeade and Cliffe. The aim was to protect the important military establishments further up river at Purfleet and Woolwich. The forts were built when there were more problems in France in the mid-nineteenth century and another invasion scare started. A Royal Commission was set up by Lord Palmerston which recommended that nineteen new forts and over fifty batteries be built. The defences including Coalhouse were known as Palmerston Forts.

COLCHESTER

As another Essex town on the way from London to the coast, Colchester has long been used to the sight of passing soldiers. From at least the seventeenth century, many of these soldiers were billeted in inns and local homes. The beginning of the French wars led to a twenty-year spell of the army being billeted in camps on Lexden Heath and eventually in barracks in the town. By the end of the eighteenth century locals were calling for barracks to be built to stop the practice of billeting in private homes.

Colchester Castle in the early nineteenth century.

Prince Albert at Wivenhoe Park in April 1856. The Prince had come to inspect the troops at Colchester. He was shown around by Sir William O’Malley, the Barrack Master of the time.

The inspection of the East Essex Rifles, at Colchester in 1868. The building in the background is the garrison church.

The French wars and the increasing number of soldiers needed in the area because of the danger of invasion were the spur for the origin of military barracks in Colchester and several other Essex towns. In many cases these new barracks lasted only until Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo. However, in other towns, such as Colchester, barracks became a permanent fixture.

The Royal Navy was as hungry for men as the army to crew their large ships and fight the French at sea. Press gangs operated in many towns, taking unwilling hands to serve before the mast. In 1795 the government also set towns and boroughs quotas of landsmen to be supplied to the navy. These men were sought through advertisements in the local newspapers. The parish of All Saints offered 20 guineas for volunteers. Other areas had trouble in finding their quota: an advertisement offering £31 for volunteers to go to sea ran for some time in the Chelmsford Chronicle, but there were few takers despite the large amount of money being offered.

Colchester had not had a permanent garrison since Roman times, but that changed when barracks were built between Magdalen Street and Old Heath Road at the beginning of the nineteenth century. These were brick built, unlike the wooden huts at both Hyderabad and Meanee barracks. Cavalry barracks were also added; these could hold 3,000 men and 5,000 horses. The cavalrymen slept in a room above the stables.

The arrival of large numbers of soldiers encouraged the growth of the local market gardening industry to supply them, and this had an immediate effect on the prosperity of the area.

As well as the regular troops, who were based at the barracks, detachments of volunteers were ready to fight if the threat of invasion became a reality. These included both infantry and cavalry. The pledge these volunteers signed was worded so that their duty could include dealing with anyone who threatened the government, not just foreign enemies.

The military camp at Colchester in 1869.

War medals being presented to the troops at Colchester barracks during the Boer War.

The increased prosperity of the town during the war led to improvements that had not been possible before, such as the building of the Theatre Royal in 1812. The new building was as popular with the officers from the barracks as it was with local dignitaries. Fashionable life in the town was no doubt enriched by the presence of officers in colourful uniforms who came from the best families in the country.

After the defeat of Napoleon in 1815 most of the barracks at Colchester were shut down and sold off. However, as the Colchester Gazette reported in May 1816, the 1st Dragoon Guards arrived in Colchester from Hounslow and the 47th Regiment arrived at Chelmsford to lodge at the barracks.

More barracks were built in the mid-nineteenth century, and by 1855 they were big enough to house nineteen battalions. They included a field which was used as a camp by the German Legion in 1856. More huts were built that year and in 1857 married quarters were added. The German Legion returned in 1868, and many of the German soldiers married local girls while in Colchester, a tradition that was to be repeated by other foreign troops in later wars.

Throughout the nineteenth century further barracks were built in the town. Goojerat and Sabraeon were built in the early nineteenth century. The barracks had brick buildings added in 1891 to replace former wooden huts.

Also, in 1856, a garrison chapel was built, on the site of an old burial ground that had been used by previous barracks. It was named after St Alban, a citizen of Verulamium who gave his life to save a Christian priest, and could hold up to 1,500 men standing. The number was greatly reduced when seats were put in. It still serves the troops in Colchester today, and is the second largest garrison church in the country.

HARWICH

Harwich has been one of the most important Essex ports for many years, and a centre of shipbuilding and naval involvement since the earliest military events in British history. The majority of the soldiers who travelled through Essex towns on their way to Europe headed there.

Daniel Defoe, on his tour of England in 1774, said of Harwich that the harbour was covered by a strong battery of guns. The guns he meant were probably on the Suffolk side of the river in Landguard Fort, but it was built so far out into the river that it was at that time seen to be in Essex. In 1667 one of the largest armed landings by an enemy force since 1066 took place at Landguard when the Dutch invaded but were beaten off.

Once again it was the war against Napoleon that spurred the need to fortify the port of Harwich on the Essex side of the river, although troops had been billeted there before this. The East Essex were at Harwich in 1782 and the Hertford Militia camped there in 1796. There is no doubt that the Harwich military camp was as big as the other summer military camps in Essex.

Harwich in the mid-nineteenth century with the defences on the left.

Landguard Fort and the entrance to Harwich Harbour, 1888. The fort was originally seen as being in Essex, although it was on the Suffolk side of the river.

One of the early iron-clad warships, HMS Essex.

The cruiser Blenheim (left) ran aground at Harwich in 1909.