Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

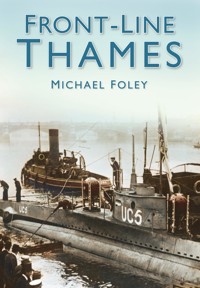

The Thames has been the highway into London since early times. Iron Age forts once guarded its banks and then Roman legionaries took over. Every age since has added to the defences lining the river. The river was also used as the site of mills to produce gunpowder and test weapons, industries too dangerous to be based close to London. The river also betrayed the site of London to enemy airships and later aircraft. Even a complete blackout of the capital could not hide the river's route from enemy pilots. Although the defences are now outdated, many of them remain, giving example of London's battle through history. Michael Foley examines all aspects of military history around the capital and along the banks of the Thames in this fascinating new book.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 204

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2008

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

FRONT – LINE

THAMES

MICHAEL FOLEY

To Beacon Hill School, South Ockendon, Essex A special place for special children, where happiness and achievement go hand in hand

All images are from the author’s personal collection unless otherwise stated.

Title page illustration: An old map of the Thames from Vauxhall Bridge to Southwark Bridge.

First published in 2008

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Michael Foley, 2008, 2013

The right of Michael Foley to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5239 2

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Introduction

1.

Before the Normans

2.

From the Normans to the Nineteenth Century

3.

From Napoleon to the Twentieth Century

4.

The First World War

5.

The Second World War to Today

Bibliography

Introduction & Acknowledgements

There are times in your life when you read a statement and you wish you had said it first. That was exactly what I thought when I read the following by the British politician, John Burns: ‘The Thames is liquid history.’ I had already realised this fact while writing previous books about Kent and Essex, two of the counties that border the river as it reaches the sea. Both of these books included details of several defensive structures either on the banks of, or close to the Thames.

The river has played such an important part in the history of the country and it was the defence of the river, especially between the tower and the sea, which first caught my imagination. However, there is so much more to the river than just the part below London. The majority of the conflicts throughout history that were enacted close to or on the river actually occurred above London. Hopefully, this book will inform some who, like me previously, thought that the Thames above the capital had always been a peaceful, serene place.

Unlike my previous ‘Front-Line’ books, which were arranged alphabetically, Front-Line Thames is compiled in the order of progression from the sea to the source.

I would like to thank Richard Milligan for reading the manuscript and for his help and suggestions and Frank Turner for allowing me to use his illustrations.

Although every attempt has been made to find the copyright owners of all the illustrations, anyone whose copyright has been unintentionally breached should contact the author through the publisher.

Michael Foley, 2008

ONE

Before the Normans

The upper reaches of the Thames may seem a quiet, rural place now. It is as the river gets closer to the sea that we think of the great defensive structures and defence against the invader. In the days before the Norman Conquest, however, the river in the Thames Valley marked the border between the territories of a number of early British tribes. In later Saxon times, the Thames marked the border between the kingdoms of Mercia, to the north of the river, and Wessex to the South.

The Thames Valley was also the site of numerous early defensive structures. The river was narrower in this area and thus easier to cross, which meant that armies travelling from north to south chose sites above London to cross; this led to the creation of these sites to defend river crossings.

The remains of the Roman Wall at Tower Hill are thought to be the only remnants of the Roman defences in London. During the nineteenth century there were plans to demolish it, which were thankfully abandoned.

The source of many of the early defensive structures are often not clear. Although they may originally date from the Bronze Age, they have often been re-used by later settling groups such as the Roman and Vikings, which often cloud their origins. The same could be said of the sites of battles, whose positions are often disputed.

The landing points of the Roman invasions have never been proved beyond doubt. There seems to a partial agreement that during the Claudian invasion there was a battle near the Medway before the Roman army stopped at some point on the Thames to await the arrival of Emperor Claudius. Where this may have been is also a matter of some conjecture.

Another lesser-known Roman invasion took place in the third century when Carausius declared himself Emperor of Britain, which led to even more dispute. The invasion led by Constantius to re-take Britain for Rome from Carausius’s killer and usurper, Allectus, took part in two separate forces. Where they landed was the basis for another dispute – one view is that the force led by Constantius actually sailed up the Thames to London.

This invasion has also led to another theory: some writers believe that the Saxon shore forts such as the one at Reculver may have been built to stop this invasion by Rome, rather than the commonly held belief that they were constructed to stop later raids by Saxons.

THANET

The Isle of Thanet played a major part in the settlement of early Kent by invaders from the continent. In 449 AD, King Vortigern asked Jutish leaders Hengist and Horsa for help against Pictish raiders. Although the Jutes originally arrived in a few ships, more of them came later and settled on Thanet. Within ten years, they had become more of a threat than an amenable ally – they eventually conquered most of Kent.

Thanet also became a Viking stronghold and the Norsemen wintered there in 851 AD. Over 300 ships anchored on the Isle’s coastline at one point; it was from here that they attacked Canterbury, defeating Beorhtwulf, King of Mercia.

Vikings still have a fierce and romantic aura as shown by their commemoration on matchbox labels such as this one.

Materials from the old Roman fort were used to build the church at Reculver, which has since disappeared owing to subsidence. The church towers were left as an aid to shipping and parts of the fort also remain.

RECULVER

The area around Reculver was probably occupied before the Romans arrived. It is believed that the Roman defences there began life as a signal station. The settlement developed into fortified barracks before becoming a fort. Its original purpose may well have been to defend the entrance to the Thames.

Reculver developed into the site of a Roman square fort, with 10ft-thick walls and round corners. There were no known bastions, although one gate was known to be in the west wall, as well as a ditch that surrounded the fortifications. The site covered around 7½ acres. It is believed by some to have been one of the Saxon Shore Forts. These were supposedly built to stop Saxon raiders as the Roman rule of Britain drew to a close.

A town grew up around the fort, which was generally in keeping with Roman military stations. The inhabitants of the town would have made their living providing services and goods for the soldiers in the fort.

During the Saxon period, King Ethelbert gave up his home in Canterbury to Augustine and built a new palace at Reculver. A monastery was also built on the site in the seventh century, using materials from the disused fort. This was abandoned once raids by Vikings made its continued existence too dangerous.

SHOEBURYNESS

It has been a long-held belief that the site of an ancient camp at Shoeburyness was in fact of Viking provenance. More recent excavations, however, have shown it was actually of Iron Age origin. The camp could well have been used by the Vikings at a much later date.

There is no doubt that there was a Viking camp at Shoebury, which was mentioned in the Anglo Saxon Chronicle. When the Viking camp at Benfleet was attacked by King Alfred, the surviving Vikings moved to Shoebury. The actual name of Shoebury is thought to be based on this horseshoe-shaped Viking camp. ‘Burh’ was the name for a fortified place and ‘sceo’ was shoe, which in this case meant horseshoe. Shoeburyness has another connection with the later barracks in the area, which were called Horseshoe Barracks.

MEDWAY

The sites of Roman invasions and the battles that took place during the conquests are always open to debate. One view of an event during the Claudian invasion of 43 AD is that a Roman army of 40,000 men under General Auluslatius fought a two-day battle against the Catuvellauni tribe somewhere close to the Medway. This could have been south of Rochester.

The Catuvellauni tribe were dominant in the south-east of the country and their capital was Colchester in Essex. The defeated Britons from the Medway battle are believed to have retreated across the Thames. The victorious Roman army supposedly waited somewhere on the Thames for the Emperor Claudius to arrive before moving on to Colchester. The Romans then took Colchester using elephants, which would have been a fearful sight for the defenders of the town, who had, no doubt, never seen such animals.

PRITTLEWELL

The remains of another ancient camp are to be found at Prittlewell. It is close to the head of the River Roach and is about 800ft by 650ft. The defences consisted of a rampart and a ditch. It seems to have been an early hill fort, which would make it one of the earliest of the Thames defences. The area around Southend seems to have been well defended from the earliest times; recent archaeological finds show that it was also an important site in Saxon times.

The camp at Prittlewell was an early hill fort. These forts were often used in times of crisis and not permanently manned.

BENFLEET

There was another fortified camp at Benfleet, which in 894 AD was occupied by Haesten and a large Viking army. According to the Anglo Saxon Chronicle, Benfleet was attacked by King Alfred’s forces, who completely routed the Vikings. They destroyed the Viking ships and took the contents of the camp, including women and children, to London. When the nineteenth-century railway was being built in the area, a large number of burnt ships and human skeletons were found which are thought to originate from this battle.

MUCKING

It is interesting that a book covering the history of Essex, Forgotten Thameside written in 1951, makes no mention of Anglo Saxon or Roman finds in Mucking but extensive excavations thereafter found evidence of large settlement of the area. Mucking was the site of an Iron Age fort, which overlooked the Thames. Hill forts in the Iron Age are believed to have been places of occasional refuge in times of conflict, rather than permanent defensive settlements, and this fort may have been used by the local farming population.

There are also signs of Roman occupation in the area, in an agricultural rather than a defensive setting. It can be safely assumed that a period of uncertainty and lack of organised government followed in the time after the Romans left. It is argued by some that Mucking may have been one of the first organised areas of defence used by the Saxons against any further invaders.

A rather romantic view of a Roman soldier from an old print with Roman ships passing in the background. The tower to the left looks more medieval than Roman, however.

RAINHAM

Rainham is close to Mucking and also had a small Iron Age enclosure dating between 50 BC and 50 AD. It had triple ditches and banks and was about 256ft by 276ft. There was an earthen rampart with a wooden palisade. Its small size must mean that it was a defendable refuge.

There were also several later Saxon finds in the area, including a very rare glass drinking horn now in the British Museum.

BARKING

The River Roding flows into the Thames at Barking and was once an important means of travel. There was an ancient Hill Fort by the Roding at Uphall. Although the site may have been from the Bronze Age, it was also used during the Iron Age. Barking is believed to have Roman connections and Roman ships may have sailed up the Roding to Uphall. The strong defensive position of the fort has also led to the belief that it may have been used by Vikings as well.

The abbey at Barking was one of the richest in the area and was attacked by the Vikings in 870 AD. This resulted in the massacre of its inhabitants, the theft of the Abbey’s treasures and the burning of the buildings. It led to a gap of around a century before the abbey was rebuilt during a lull in attacks by the Vikings.

GREENWICH

Although Greenwich was close to the route of the Roman road of Watling Street, no evidence of a large Roman settlement has been found there. There have been a number of Saxon burials found in the area, dating from around the seventh century.

One group that did spend time at Greenwich, and used it as a defended base, were the Vikings. In 1012 they wintered in the area and used it as a base to raid Canterbury, where they slaughtered many of the town’s inhabitants. They took Aelfheah, the archbishop, hostage but, when they were unable to get a ransom, they killed him during a drunken feast.

Although the sight of longboats may have struck terror into the people at the time, they are now nothing more than a romantic form of illustration for a matchbox.

RIVER LEA

A strong Viking force was camped on the River Lea when King Alfred supposedly changed the course of the river to stop the Vikings from using their ships; they then fled overland. It is thought that there may be some truth behind this legend; Alfred may have actually reopened a silted-up channel of the river, which made the water level drop and prevented the Vikings from sailing further upriver.

LONDON

Despite the theories of some academics, it is unlikely that a pre-Roman town existed where London is now situated. Those who do believe that a Celtic village or fort preceded the Roman town believe it was called Lynn-Din. It is not even clear if this was where, as is often argued, Julius Caesar first crossed the Thames. It is thought, however, that the Romans built a bridge across the river somewhere in the vicinity of London quite early in their occupation.

There seems to have been a Roman settlement on the south bank of the river. It was described by Tacitus as a place of merchants. This could have been a civilian settlement near Southwark, while a military fort stood on the north bank; this is proven by the remains of the wall that surrounded it. Ptolemy described London as a city of Kent, so this seems to bear that out.

Part of a sarcophagus found at Tower Hill in the nineteenth century.

The Roman Wall at Tower Hill is the lower part of this structure. The medieval wall was built on top.

There are remains of the Roman wall at Tower Hill. In the mid-nineteenth century, there were plans to pull the wall down but, thankfully, this was stopped. It is thought to be the only remains of the Roman wall in London, although only the lower part is Roman. The medieval wall was later built on top of it.

Stones from a Roman building were also found at Tower Hill when the base of the wall was discovered during excavations in 1852. This discovery included part of a sarcophagus found by a workman tapping his foot against it while eating his dinner. This had an inscription cut into it.

When County Hall was being built in 1910, the remains of a Roman ship were found, dating from around the end of the third century. Although built in the Roman style, the material used was timber from the south of England.

After the Romans left, there is some doubt about how important London was. The Saxons did not have much use for towns, but there must have been a native population; it was much later that London became an important Saxon town.

When the Vikings began to raid the country in the ninth century, they often sailed up the Thames to attack settlements and abbeys both north and south of the Thames. They attacked London itself in 839 AD. In the late ninth century, the Vikings wintered on the Thames close to London where they killed the Archbishop of Canterbury who they had taken hostage. The Vikings occupied London itself from 872 AD. When Alfred defeated the Vikings in 886 AD, he began to use the old walled town as a defensive position. It is believed to be from this point that London became the centre of much of what happened in England.

A statue of a Roman at Tower Hill, thought to be the Emperor Trajan.

In 994 AD, Swein attacked London with ninety-four ships but was driven off. He returned in 1013 and drove King Ethelred away. Swein died the following year and his son Canute became king. He was then driven out of London by the vengeful Ethelred but returned with 340 ships. Canute supposedly dug a channel and pulled his ships round London Bridge. They were again driven off but, after a battle at Ashingdon in Essex, Canute was victorious and reclaimed the throne.

The Godwin family were later to become one of the most powerful families in the country until they fell out with King Edward the Confessor, lost their lands and were banished. In 1052, the Godwins returned in force and sailed unopposed up the Thames to London. When they landed at Southwark they were cheered by the population. Edward’s army faced them from the northern bank of the river. The Bishop of Winchester eventually mediated and Godwin was given his lands back after swearing allegiance to the king. They were reunited with Edward, and Harold Godwin became king after Edward’s death.

A plaque mounted on a wall at Tower Hill which is a copy of an inscribed stone found there in the nineteenth century.

BRENTFORD

Brentford is one of many sites where it was claimed that Julius Caesar crossed the Thames. This was to attack Cassivellanus at Verulam. Later armies also used the ford to cross the river here.

In 1016, Edmund Ironside gathered a large army and crossed the Thames at Brentford to defeat the Danes there. He crossed the Thames by the ford and defeated their army on the south bank. Large numbers of the king’s men were drowned when they went in front of the army trying to seize loot. It also seems that Edmund crossed the river at Brentford several times in pursuit of the Vikings.

KINGSTON UPON THAMES

A number of Roman camps have been discovered in the area of Kingston. Sometimes the description of a camp can be misleading for the Romans normally created earthworks and a ditch around their camps, even if they were only there for one night. A camp may, therefore, be nothing more than a one-night stop over.

In 838 AD, Kingston was the site of the Witan of King Egbert and supposedly the site of the coronation of seven Saxon kings, who used the coronation stone, which is now placed near the Guildhall. The seven kings crowned there were: Edward the Elder in 899 AD; Athelstan in 924 AD; Edmund I in 939 AD; Edred in 946 AD; Edwy in 955 AD; Edward the Martyr in 975 AD and Ethelred II in 979 AD. Kings in those days obviously did not last very long ….

A drawing of the King’s Stone used during the coronations of seven Saxon kings at Kingston-upon-Thames.

The position of the King’s Stone in Kingston in the early twentieth century.

CHERTSEY

There was a Benedictine abbey at Chertsey founded by Erkenwald, the Bishop of London, in 666 AD, and it had strong connections with the one at Barking. Both were founded by Erkenwald and, while he was the abbot at Chertsey, his sister was in charge at Barking. Both abbeys were destroyed by the Vikings.

Chertsey was destroyed in 869 AD when Abbot Beocca and nearly a hundred priests were slaughtered. The abbey was re-founded by King Edgar in 964 AD.

READING

Reading featured in the conflict between the Vikings and the Saxons on a number of occasions. The Danes made a base there in 871 AD for their campaign against Wessex. There was a battle between an ealdorman named Aethelwulf and the Vikings, which Aethelwulf won. A few days later, King Ethelred and his brother Alfred led a large army to Reading. There was a long battle during which Aethelwulf was killed. It seems that the Vikings were undefeated because the following year they went from Reading to London. In 1006, a Viking army returned to Reading to undertake yet more raiding.

Viking warriors making ready to attack land-based defences.

Streatley Hill overlooks the Thames where it was once the border between the Saxon kingdoms of Wessex and Mercia.

WALLINGFORD

Although thought to have Roman origins, the town of Wallingford is believed to have later become a fortified Saxon town. It also played its part in the battle against the Vikings. In 1006, an army of Danes, who had wintered on the Isle of Wight, attacked Wallingford and, in the words of the Anglo Saxon Chronicle, ‘scorched it all up.’

In 1013, Swein’s army attacked London but, after being driven off, came to Wallingford to cross the Thames on their way to Bath.

DORCHESTER

Dorchester was the site of large Iron Age earthworks on Sinodun Hill, which showed its strategic position. This was capitalised on by the Romans and Dorchester became a Roman town. There are other old defensive works, such as Dyke Hills, which may have been Roman, that were made to face the British fortifications. There was also thought to have been a channel linking the Thames and the Thame as an extra defensive ditch.

Dyke Hills, Dorchester, are the remains of old defensive earthworks, believed by some to be of Roman origin, which were built to oppose nearby British defences.

THE WITTENHAMS

There are two Wittenham villages, Long and Little, about a mile apart. There was a nearby Iron Age fort on Castle Hill. Celtic, Saxon and Roman graves and artefacts have been found in the area. This included an Iron Age sword and scabbard found close to Day’s Lock. It was thought that the fort was an Atrebates stronghold, where they fought against the invasion of Julius Caesar. This may not have been quite accurate, but no other definite answer as to its origins are in place. The fort may have later been used by the Romans.

Day’s Lock was the site of a find of an Iron Age sword.

Wittenham was the site of an Iron Age fort, which is believed to have been an Atrebates stronghold from where they fought the Romans under Caesar.

ABINGDON

A large Iron Age defensive structure was discovered in Abingdon in the 1990s. It had a number of defensive ditches and used the Thames and its tributary, the Ock, as defensive barriers. It was also used during the Roman period.

KEMPSFORD

Kempsford was supposedly the site of a Saxon palace. In 800 AD, Ethelmund, Ealdorman of the Wiceii, crossed the river there and attacked Weohstan of the Wilsceti – both men were killed. The Wilsceti from Wiltshire seemed to have been victorious. Some relics, perhaps from the battle between the Saxon armies, were found in the area in 1670.

CRICKLADE

The river at Cricklade is quite narrow but nevertheless it was an important barrier as it was the frontier of Wessex during Saxon times. It was often used as the crossing point for numerous armies on their way to battle. King Alfred supposedly crossed the river here when going to fight the vikings. Ethelwold crossed the river there in 905 after a raid into neighbouring Mercia and Canute also crossed the river at Cricklade in 1016 on a mission to burn and loot Warwickshire. There was thought to have been a Saxon burgh in the area to defend the river which would seem to be a reasonable assumption owing to its use as a river crossing and as the Vikings seem to have been regular visitors to the area.