Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

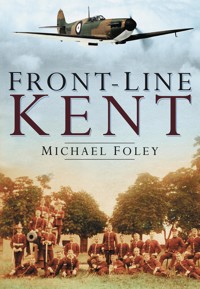

Kent has been on England's first line of defence. In all major conflicts many people in the county have lived closer to the enemy in Europe than they did to London. Much of the county's coastline has been the site of training and weapon development, which adds to the interest of military sites in this area. Michael Foley's new book delves into the long history of military Kent, from Roman forts to Martello towers, built to keep Napoleon out, from the ambitious Royal Military Canal, which cost an equivalent of GBP10 million in today's money but was abandoned after seventy years, to wartime airfields and underground Cold War installations. Illustrated with a wide range of photographs, maps, drawings, engravings and paintings, Front-Line Kent also includes location and access details for the sites that are illustrated and described. This lively and informative book will appeal to anyone interested in Kent's history, whether or not a military specialist.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 210

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2006

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

FRONT-LINE

KENT

MICHAEL FOLEY

To Liam and Lewis, two special boys who changed my life.

First published 2006 by Sutton Publishing Limited

Reprinted in 2010 by

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Reprinted 2011

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Michael Foley, 2011, 2013

The right of Michael Foley to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5331 3

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1

From the Romans to the Normans

2

From the Normans to Napoleon

3

From Napoleon to the Twentieth Century

4

From 1900 to the Present Day

Bibliography

One of the fortified entrances to Sandwich, the Fisher Gate. The original town walls date from the Norman period.

Acknowledgements

I should like to thank the following for granting me permission to use their illustrations: Barry Stewart of Underground Kent, English Heritage and Alan Filtness. All other illustrations are from my private collection. I should also like to thank Barry Stewart and Alan Filtness for their help in obtaining illustrations.

Although every attempt has been made to find the copyright owners of all illustrations used, anyone whose copyright has been unintentionally breached should contact me through the publisher.

A silk of the 1st Battalion of the East Kent Regiment.

Silk of the Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment.

Although famous for his time in China and the Sudan, General Gordon also had close connections with Gravesend. The picture shows the Gordon Memorial at Chatham.

Introduction

As one of the closest English counties to the Continent, Kent has always been one of the most likely points of invasion. Thus, the inhabitants of Kent’s south coast have often lived nearer to the country’s enemies than its capital, London, some 80 miles away. And of course, there have been many examples of successful invasions to instil the fear of them into Kentish minds. It was on this stretch of coast that the first full-scale invasion of our island took place, when Julius Caesar landed his legions at Deal, in the days before the county of Kent existed. Added to the vulnerable south coast of the county is an east coast that has suffered numerous attacks, and a Thames river line that has always served as a convenient route to London. The county of Kent has faced attack from the Dutch, Spanish and French on untold occasions, and the words of Napoleon Bonaparte reflect the ambitions of many would-be invaders: ‘Let us be the masters of the Channel for six hours and we are masters of the world.’

During the First World War the coastal towns of Kent were bombarded by Zeppelins, aircraft and warships. And in the Second World War they were one of the only places in Britain to be shelled from occupied France. No wonder, then, the coast of Kent has been reinforced with numerous tunnels, defences, and shelters throughout history.

But the building of shelters and defences did not end with the defeat of Germany. The end of the Second World War threw up a new foe with even deadlier weapons: so Cold War defences were created, often alongside older buildings, and often in secret. It was not invasion that was feared, however, but long-range missiles, so not all the new defences were built near the coast. Nevertheless, the county of Kent is undoubtedly in England’s front line and always has been.

A view of the Royal Navy Barracks at Chatham, with band playing for a civilian audience.

The garrison church parade at Woolwich, with civilian sightseers.

1

From the Romans to the Normans

When the Romans arrived on Kentish soil for the first time they encountered little in the way of defensive structures. Although some scattered hill forts existed, most of the fighting took place in open battles, which, unfortunately for the British tribes, the Romans excelled at. There were some twenty tribes in Britain at the time of the first invasion, and the extent of their territories varied, depending on how successful they were at defending their borders – from each other.

There were at least four Roman invasions: the first, by Caesar in 55 BC, was little more than an armed raid. The main reason for this invasion seems to have been that Caesar wanted to keep his name before the Roman public by achieving personal glory. The invasion was a disaster, with the cavalry unable to get across the Channel due to bad weather. And when Caesar’s men finally did manage to fight their way ashore, many of their ships were destroyed by high tides and foul weather.

Roman military tactics were well known for centuries, as this seventeenth-century engraving of a Roman Testudo shows. Manoeuvres such as the Testudo must have amazed the tribes facing the Romans.

Nevertheless, Caesar returned the following year, 54 BC, landing at Deal with a larger force. And this time he had cavalry. Some believe he also had an elephant, which apparently terrified the tribesmen, who had never seen such a large beast. Although more successful on this occasion, the Romans returned to Gaul when winter came. The Britons that Caesar met on this second occasion were better organised than he had expected, having put aside their differences and united under Cassivellanus. They also displayed advanced military tactics in the use of chariots.

The first Roman defences in the county were erected when the Romans came back in AD 43. This invasion was led by Aulus Platius for the Emperor Claudius, who joined him later with elephants. The final invasion in 296, led by Constantius Chlorus, was a result of Carausius declaring himself Emperor of Britain.

When the Romans went home in the third and fourth centuries they left a land open to invasion. The Saxons came to displace the Celtic tribes of Britain. The Saxons were then attacked by ferocious invaders from further north. Like the Saxons, these Viking pirates simply raided initially, and then began to settle. The first sites targeted during raids were monasteries. As major landowners the monasteries had amassed vast wealth by the eighth century, but were often in isolated positions. By 870 many monasteries in Kent had ceased to exist, and Wessex was the only independent Saxon kingdom left in Britain.

The Vikings tried to dominate the county of Kent but were defeated in a series of battles by Alfred and his sons. Although raids seem to have begun in the early ninth century, soon the Vikings were staying for the winter, erecting defences at Rochester in 885 and Sittingbourne in 892. Alfred established a series of Burghs in his kingdom, so that every 20 miles there was a place of refuge for those who were attacked. In Kent, many older towns with defensive walls – such as Canterbury, Rochester and Dover – were used in the same way.

Even after Alfred’s death, the Viking threat did not end. It took another century for the Northmen to be finally defeated: but by then England had another foe to worry about.

CANTERBURY

Canterbury was already a native settlement when the Romans arrived. It was situated at a fordable spot on the River Stour. An Iron Age earthwork was situated close by at Bigbury, and this is probably the fort where Caesar found the Britons on the occasion of his second incursion, in 54 BC.

When the Romans came back to stay, Canterbury became an important link in their road system. It was a good central town for contact with the coastal forts and London. It was also on the route of Watling Street, where it crossed the River Stour. The southern part of the country needed little in the way of defences, as there were few uprisings. However, as an important road junction, Canterbury needed a military presence. Because of this, walls were built around the town, perhaps in the third century, as protection against Saxon pirates. The town also contained barracks. The Roman city covered some 50 acres – roughly the same size as the Medieval city.

After the Romans quit, the Jutes under Hengist and Horsa arrived as mercenaries to help the locals repel Saxon raiders. They quickly became dissatisfied with the Isle of Thanet – given to them in payment for their services – and conquered all Kent. When they came to Canterbury there was little to oppose them: the post-Roman settlers had little use for towns, which often became deserted, and it was only later that Canterbury became the capital of Kent.

The first Viking attacks came in the early ninth century, and at one point the inhabitants of Canterbury fled from the Danes based at Sheppy. The city was sacked in 839 and in 850, but without much killing it seems. Alfred’s victory over the Danes at Ethandune in 878 gave the city some respite. In 1011, however, the most serious attack occurred on the city. After a short but gallant defence on the part of the inhabitants, the Danes took the city. There was terrible slaughter, and it is thought that only 800 of the 7,000-strong population survived to be sold into slavery. The Vikings also took Archbishop Aelfheah hostage. But the Archbishop would not permit a ransom to be paid for him, and he was finally killed after seven months’ captivity at Greenwich.

A couple of miles away from Canterbury lies the town of Fordwich, on the River Stour. It has long been associated with Sandwich, and was included as one of the Cinque Ports, contributing to the coastal defence of the country before the Royal Navy was formed.

Fordwich has Roman origins, as indicated by the many artefacts found there. The town had an unusual method of executing condemned criminals: it seems they were drowned, the prosecutor holding the felon under water till he or she stopped breathing.

The town’s connection with Canterbury began when the monks from Canterbury were given land in the area, and built their own quay in opposition to the one used by the town. Fordwich then became Canterbury’s port and much of the building materials for the Cathedral and other buildings were brought in by ship.

DEAL

Deal was once the main harbour of south-east England. Caesar supposedly beached his galleys here in 55 BC. He found Belgic tribesmen waiting with cavalry and chariots, and there is a view that these warriors were little more than savages, almost naked, and painted blue. And yet Britain had been trading with Gaul and several other countries for many years before Caesar came – perhaps the Britons of the time were not as savage as the Romans would have us believe?

A Roman warship as used by the invading troops in the second invasion. It was supposedly at Deal that Caesar’s ships landed.

DOVER

Dover has always been the gateway to England. However, Caesar found the gates shut when he arrived in 55 BC. The Romans were supposedly attacked from both hillsides, so Caesar took his fleet along the coast to Deal instead.

Dover was already the site of an Iron Age fort. The Romans began building their own fort in AD 117. They built a second fort for the protection of the fleet in 130, and a third fort in the late third century, as part of the defences against Saxon raiders. However, some believe that the Saxon Shore forts were built by Carausius as a defence against Rome, after he had declared himself Emperor in Britain. The only remains of Roman defences in Dover were some earthworks, which were destroyed by later structures.

Dover was also the site of Roman lighthouses – rare structures in Britain. The Roman Painted House was also discovered in the town, thought to have been the quarters of a naval official. It was preserved when a later fort was built over the top of it.

As a fort from the earliest times, Dover – unlike other places in the county – has never been allowed to disintegrate. It has always been too important to the ruling power. Raids by Saxons and Jutes began in around 443, roughly thirty years after the Romans left.

A church was built on the site of the Roman fort, supposedly by Eadbalb, an early Saxon King of Kent, for his sister Ethelburga. Churches in Saxon times did not have the respect of all, so they were built with defences around them, including, in this case, earthworks and a tower. The defences developed over time and several more towers were added during the Saxon era.

This nineteenth-century plan of Dover Castle shows how the defences have developed from the earliest times.

An old print of the ancient Saxon church and remains of one of the Pharos or Roman lighthouses at Dover.

FOLKESTONE

Ruins have been found in Folkestone dating from the Roman invasion of AD 43, but it was never a major Roman port, owing to the lack of a river or harbour. It was more of a lookout point and small military base. Folkestone was also the site of an ancient fort, dating from the Iron Age, or later, but despite being called Caesar’s Camp it was not Roman.

After the Romans left, the Germanic invasions and raids began, causing many coastal people to move inland. Folkestone and other coastal areas were then uninhabited for some time. By the seventh century Kent had become a Saxon kingdom, and in 630 King Eadbald decided to build a church and nunnery. He also built a castle to protect them. The settlement was attacked by Vikings in 927 and destroyed, but later rebuilt.

On the hill is the site of old fortifications that probably predated the Roman invasion, but which became known as ‘Caesar’s Camp’. It is possible that the site was used as a temporary camp by the Roman invasion force.

A Viking longship – a sight that struck fear into the local population. In 1012 the Vikings wintered at Greenwich but stayed for years.

GREENWICH

Greenwich was on the route of Watling Street, which passed through it close to the Thames. Although remains of a temple have been found, no indications of a major Roman settlement have been discovered. However, several seventh-century Saxon warrior-burials have been unearthed: an unusual find, as much of Kent was controlled by Jutes at that time.

Another group that spent much time at Greenwich were the Vikings. They wintered in the area in 1012, eventually remaining for years. During their sojourn they besieged Canterbury and slaughtered many of its inhabitants. They also took Aelfheah, Archbishop of Canterbury, prisoner, holding him at Greenwich. When no ransom was forthcoming they slaughtered him after a drunken feast. Their leader, Thurkill, was so disgusted at the murder that he changed sides, taking his ships over to Ethelred. But even this did not deter the Vikings, who remained long after.

LYMINGE

The name Huckbone has played a prominent part in the history of Lyminge. It has been claimed that members of the family paid tribute to the Romans in AD 47 but then later fought the invaders. A man named Hubene is recorded as Lord of the Manor in the Domesday Book, and another, Hogben, which is thought to be the modern spelling of the name, was made a baron by Henry I.

There was a famous monastery in Lyminge, founded by Ethelburga, daughter of Ethelbert, King of Kent in 633. Ethelburga had married the King of Northumbria, who died in 633, when she returned to Kent. The monastery was in use by men and women until it was destroyed by the Danes in 840. It stood on an exposed site, north of Romney Marsh. The inhabitants fled to the walled town of Canterbury for safety.

LYMPNE

The Romans built a small fort here in the first century, which may not have been used as part of the Claudian invasion. It was perhaps a later safe haven for those on the journey to the mining areas of the West Country. There was a road from the port to Canterbury known as Stone Street, which was lined with Roman villas.

An old print showing the remains of Studfall Fort, one of the Saxon Shore forts, which stands below the more recent castle.

The main fort was built in the third century and lasted into the fourth, supposedly to deter Saxon raiders. The Saxon Shore forts were built close to harbours. Lympne was a strategic site, looking out to Romney Marsh, with a view of France on a clear day. The walls of the fort were 14ft thick and 23ft high. Some remains can still be seen, but most have collapsed or slid down the slope, the castle having been built too close to the sea. The fort was given a Saxon name – Studfall – after the Romans left. In AD 892 250 Viking ships arrived at Lympne as part of a new invasion force.

The ruins of the Roman fort were used in the construction of another castle on the site in the time of Henry V.

MARGATE

Close to Margate is Hackendown Point, which is supposedly the site of a battle between the Danes and the Saxons in about AD 853. Just as there is no proof of a battle occurring, there is no record of which side won. The Danes were supposedly led by Duke Wada, and the Saxons by Earl Alcher of Kent and Earl Hunda of Surrey. Two large barrows in the area have been found to contain graves from the period, and it is thought they may be victims of the battle. The site of the supposed battle was marked by the erection of a tower.

MEDWAY

After landing his army of 40,000 in AD 43, General Aulus Platius fought a two-day battle against the Catuvellauni close to the Medway, probably south of Rochester. The Catuvellauni tribe had been dominant in the south-east, with their capital at Colchester. The defeated Britons retreated across the Thames. After the Roman victory the Emperor Claudius arrived to take command.

OTFORD

In AD 774 King Offa of Mercia fought a great battle at Otford against the men of Kent led by Aldric. The victor of the battle is not recorded, but as Kent became independent following the fight, the Kentish men most likely won. Kent was one of the first kingdoms of the Germanic invaders, when the Jutes conquered the county in the fifth century. It was at its most powerful under Ethelbert in the seventh century.

Offa was King of Mercia from 757 until his death in 796. He was ruler of one of the most powerful Saxon kingdoms, until Wessex took over this role in the ninth century. It is clear Kent was ruled by Offa at some point, and the county may have been ruled by kings who were subservient to Offa until the battle at Otford. After this, in 784, there was a King of Kent named Ealhmund, but by 785 it seems Offa was once again in control. Otford was at some point given by Offa to the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Control of Kent was not without problems. As well as having to fight natives of the county, from 792 Offa was also obliged to build defences against pagan peoples.

The Vikings were probably conducting small raids for some time before large-scale attacks began. Otford became a battlefield again in 1016, when Edmund Ironside fought and beat an army led by Cnut. It is said that on that day the River Darent ran red.

RECULVER

There is evidence of Iron Age habitation in the Reculver area, which shows the place was occupied long before the Romans arrived. Roman Reculver apparently started life as a fortified barracks rather than a fort, during the invasion of AD 43. There is a notion the site was a signal station or even a lighthouse, but it may have been built to protect the approaches to London. It seems this small fort – covering approximately an acre – was then abandoned, until it was rebuilt as the first Saxon Shore fort.

A small town grew up around the fortifications, offering a social life for the soldiers. Much of this town has been overtaken by the sea, although evidence of small huts has been found to the west of the fort.

Ruins of the Roman fort at Reculver and the towers of a later church. The church was demolished in the early nineteenth century before it fell into the sea, but the towers were left standing to aid shipping.

By the early third century a fort was built with walls 10ft thick. It was constructed by Carausius, the self-styled Emperor of Britain. At one time there were probably as many as four gates in the fort, with perhaps a ditch or two surrounding the structure. It was supposedly built for protection against Saxon raiders, but may have been a defence against Rome, after Carausius declared himself Emperor. There is evidence that in the fourth century it was garrisoned by 500 legionaries from the borders of Gaul and present-day Holland. It is even thought these men may have built the fort.

There were several structures inside the fort, the largest being the headquarters building, which was over 100ft square. There were also barracks for the men and officers’ quarters, which had painted plaster walls. There also seems to have been a bathhouse.

During the Saxon period, King Ethelbert gave up his home in Canterbury to St Augustine and built a new palace at Reculver. A monastery was built on the site in the seventh century and the church was constructed using materials from the Roman fort. The monastery remained in use until the Viking raids began, when most coastal monasteries in Kent were abandoned. It was destroyed by Vikings in the ninth century.

The present towers belonged to a church added in the twelfth century. The church was demolished in the nineteenth century before it fell into the sea, but the two large towers were left as a navigational aid for ships. Fragments of the fort’s southern and eastern walls remain.

RICHBOROUGH

Richborough was the site of a temporary camp during the invasion of AD 43. The area was protected by a series of ditches and earthworks. It is thought that once the invasion became established, Richborough became the naval supply base for the Roman Army. Roads were built from the site to Canterbury and London. Several buildings were constructed on the site for various uses. Some believe the Roman forts grew out of temporary marching camps, which expanded to meet the needs of long-term occupation. Richborough was the Roman gateway to Britain and a large town grew around the fort. Although the fort stood on the coast in Roman times, its ruins now lie a mile inland.

A triumphal arch was supposedly built on the site to commemorate the Claudian invasion and may have been the gateway to Britain for those disembarking in the harbour. The original small settlement eventually grew into a large town. There was even an amphitheatre, which shows the importance of the settlement.

During the third century extensive defences grew in the area, consisting mainly of earthworks and ditches, which led to the destruction of part of the town. They were replaced in about AD 270 by the stone defences, which created one of the Saxon Shore forts. The walls were some 500ft long, enclosing an area of around 5 acres. The walls were 11ft thick and stood 25ft high. There were towers at certain points along the walls and turrets at each corner. There were at least two gates. The triumphal arch was supposedly removed, but it may have survived as a watchtower.

The Roman remains aroused interest in the distant past, as this eighteenth-century print of the Castrensian Amphitheatre shows.

There was a further landing at Richborough when, in 364, Britain was under attack by the Picts, Scots, Saxons and the Attacoti (likely ancestors of the Irish). By 367 the Emperor Valentinian received news that many of these had formed a conspiracy to take over the country. Meanwhile, many soldiers from the forts were deserting. In 368 Theodosius landed at Richborough with his army and conquered the barbarians. Thereafter, the fort was in use by the Romans until they quit the country at the end of the fourth century.

ROCHESTER

Rochester was a Celtic settlement of the Belgae people before the Romans took it over. It became the crossing point of Watling Street over the Medway, and what began as a fortified Roman camp became a walled city. The Roman city was believed to have covered about 24 acres. It later became a Saxon town. The Vikings first attacked in 842, leading King Alfred to build the country’s first navy there to combat them. Alfred’s ships were faster and bigger than the Viking longboats, with more oars and more space for fighting men.

ROMNEY