Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

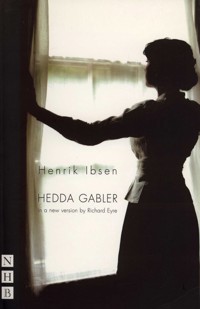

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: NHB Classic Plays

- Sprache: Englisch

Richard Eyre's version of Ibsen's Ghosts is a fresh and vivid depiction of a woman who yearns for emotional and sexual freedom, but who is too timid to achieve it. Helene Alving has spent her life suspended in an emotional void after the death of her cruel but outwardly charming husband. She is determined to escape the ghosts of her past by telling her son, Oswald, the truth about his father. But on his return from his life as a painter in France, Oswald reveals how he has already inherited the legacy of Alving's dissolute life. Richard Eyre's version of Ghosts was first staged at the Almeida Theatre, London, in 2013. This edition contains an introduction to the play by Richard Eyre.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 86

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Henrik Ibsen

GHOSTS

in a new version by

Richard Eyre

from a literal translation by

Charlotte Barslund

with an Introduction by Richard Eyre

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Title Page

Introduction

Original Production

Characters

Act One

Act Two

About the Authors

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

Introduction

Richard Eyre

Ibsen said of Ghosts that ‘in none of my plays is the author so completely absent as in this last one’. Nine years later, when he was sixty-one, Ibsen met an eighteen-year-old Viennese girl and fell in love. She asked him to live with her; he at first agreed but, crippled by guilt and fear of scandal (and perhaps impotence as well), he put an end to the relationship. Emilie became the ‘May sun of a September life’ and the inspiration for the character of Hedda Gabler, even if Ibsen himself contributed many of her characteristics with his fear of scandal and ridicule, his apparent repulsion with the reality of sex, and his yearning for emotional freedom.

Perhaps his disavowal of authorial presence in Ghosts was a little disingenuous. When he was working on the play he wrote this to a friend:

‘Everything that I have written is most minutely connected with what I have lived through, if not personally experienced… for every man shares the responsibility and the guilt of the society to which he belongs. To live is to war with trolls in heart and soul. To write is to sit in judgement on oneself.’

The audience for a play has to be left with the impression that the characters exist independently of the writer and have come to life spontaneously. ‘Sitting in judgement on oneself’ means mediating one’s ideas, emotions and anxieties through one’s characters, who in their turn have to absorb the subject matter into their bloodstream – in the case of Ghosts: patriarchy, class, free love, prostitution, hypocrisy, heredity, incest and euthanasia. In that sense, Helene Alving, the protagonist of Ghosts, is as much an autobiographical portrait as Hedda: yearning for emotional and sexual freedom but too timid to achieve it, a rebel who fears rebellion, a scourge who longs for approbation and love. ‘Ghosts had to be written,’ said Ibsen, ‘I could not let The Doll’s House be my last word. After Nora, Mrs Alving had to come.’

Ibsen’s great women characters – Nora, Hedda, Rebecca West, Hilde Wangel, Petra Stockmann, Helene Alving – batter against convention and repression. Some, like Nora, triumph; others, like Helene, fail. Ibsen empathises, actually identifies, with women both as social victims and as people. ‘If I may say so of an eminently virile man, there is a curious admixture of the woman in his nature,’ said the eighteen-year old James Joyce. ‘His marvellous accuracy, his faint traces of femininity, his delicacy of swift touch, are perhaps attributable to this admixture. But that he knows women is an incontrovertible fact. He appears to have sounded them to almost unfathomable depths.’

Yet in spite of – or is it because of? – his sympathy for women and morbid view of the state of society, you emerge from Ghosts with a sense of exhilaration, albeit underscored by the conclusion that it’s impossible to achieve joy in life. In the face of the bones of true experience, you feel that the great enemy, apart from social repression and superstition, is to be bored with life and indifferent to its suffering. ‘The voice of Henrik Ibsen in Ghosts sounds like the trumpets before the walls of Jericho. Into the remotest nooks and corners reaches his voice, with its thundering indictment of our moral cancers, our social poisons, our hideous crimes against unborn and born victims,’ said the great political activist, Emma Goldman. As with Chekhov, Ibsen sees boredom and indifference as insidious viruses that infect all society.

Ghosts was written when Ibsen was living in Rome between the spring and autumn of 1881. It was customary to publish plays before they were performed, and the play appeared in bookshops in Denmark in December. He anticipated its reception: ‘It is reasonable to suppose that Ghosts will cause alarm in some circles; but so it must be. If it did not do so, it would not have been necessary to write it.’ He wasn’t to be disappointed. There was an outcry of indignation against the attack on religion, the defence of free love, the mention of incest and syphilis. Large piles of unsold copies were returned to the publisher, the booksellers embarrassed by the presence of the book on their shelves.

Ghosts was sent to a number of theatres in Scandinavia, who all rejected the play. So it was first performed by Danish and Norwegian amateurs in a hall in Chicago in May 1882 for an audience of Scandinavian immigrants. The play was staged in Sweden the following year and this production then appeared in Denmark and, in late 1883, in Norway, where the reviews were good and it ran for seventy-five performances. Even the King of Sweden saw it and told Ibsen that it was not a good play, to which, in some exasperation, Ibsen responded: ‘Your Majesty, I had to write Ghosts !’

In England the Lord Chamberlain, the official censor, banned the play from public performance, but there was a single, unlicensed, ‘club’ performance in 1891 on a Sunday afternoon at the Royalty Theatre. It detonated an explosion of critical venom: ‘The experience of last night demonstrated that the official ban placed upon Ghosts as regards public performance was both wise and warranted’; ‘The Royalty was last night filled by an orderly audience, including many ladies, who listened attentively to the dramatic exposition of a subject which is not usually discussed outside the walls of an hospital’; ‘It is a wretched, deplorable, loathsome history, as all must admit. It might have been a tragedy had it been treated by a man of genius. Handled by an egotist and a bungler, it is only a deplorably dull play’; ‘revoltingly suggestive and blasphemous’; ‘a dirty deed done in public’.

In case we bask in the glow of progress and the delight of feeling ourselves superior to our predecessors, it’s worth remembering that the response to Edward Bond’s Saved in 1965 and Sarah Kane’s Blasted thirty years later was remarkably similar.

Shortly after Ibsen’s death in 1906, the director Max Reinhardt asked the painter Edvard Munch to design the set for the production of Ghosts that was to open his new intimate theatre in Berlin. Munch had no experience of stage design but helped the actors by doing sketches of the characters in different scenes, expressing what was going on in their minds. He designed a set that surrounded realistic Biedermeier furniture with an expressionistic setting, walls of sickly egg-yolk yellow fading to ochre. ‘I wanted to stress the responsibility of the parents,’ he said, ‘But it was my life too – my “why”? I came into the world sick, in sick surroundings, to whom youth was a sickroom and life a shiny, sunlit window – with glorious colours and glorious joys – and out there I wanted so much to take part in the dance, the Dance of Life.’

Munch, profligate and alcoholic, feared syphilis as much as he feared madness. It’s often said that Ibsen misunderstood the pathology of syphilis, that he thought – as Oswald is told by his doctor – that it was a hereditary disease passed by father to son. It’s much more probable, given that he had friends in Rome who were scientists (including the botanist J.P. Jacobsen who translated Darwin into Norwegian), that he knew that the disease is passed on through direct contact with a syphilis sore in the sexual act, and that pregnant women with the disease can pass it to the babies they are carrying. He knew too that it’s possible for a woman to be a carrier without being aware of it, and perhaps he wants us to believe even that Helene knows she is a carrier. It’s a matter of interpretation.

Which is, of course, what lies in the process of directing a play and translating it: it’s a matter of making choices. The first choice – and the first indication of the difficulty of rendering any play into another language – is what title to give the play. When the play was first translated into English by William Archer (who later, with Harley Granville-Barker, wrote a prospectus for a National Theatre), Ibsen disliked the title. The Norwegian title, Gengangere, means ‘a thing that walks again’, rather than the appearance of a soul of a dead person. But Againwalkers is – forgive the pun – an ungainly title, Revenants is (a) awkward, and (b) French, whereas Ghosts has a poetic resonance to the English ear.

I wrote this version of Ghosts six years ago when I was waiting for a film to be financed and was all too aware of the insidious virus of boredom. For some reason I couldn’t stop thinking of Oswald’s ‘Give me the sun…’ and I read the play, not having seen it for at least twenty years, with a sense of discovery: I had remembered it as a play about a physical disease and forgotten that the disease is both real and a metaphor for a rotting society. The producer, Sonia Friedman, commissioned it with a view to presenting it in the West End. It didn’t get produced because, like a troll appearing above a mountain, another production popped up and waved it away.

I worked from a literal version by Charlotte Barslund, and I tried to animate the language in a way that felt as true as possible to what I understood from them to be the author’s intentions – even to the point of trying to capture cadences that I could at least infer from the Norwegian original. But even literal translations make choices and the choices we make are made according to taste, to the times we live in and how we view the world. All choices are choices of meaning, of intention. What I have written is a ‘version’ or ‘adaptation’ or ‘interpretation’ of Ibsen’s play, but I hope that it comes near to squaring the circle of being close to what Ibsen intended while seeming spontaneous to an audience of today.

The last play I directed for the Almeida Theatre was a play about the poets Edward Thomas and Robert Frost. If there is a poem that comes to mind when I think of Ghosts, it is Frost’s poem ‘Fire and Ice’:

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.