62,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

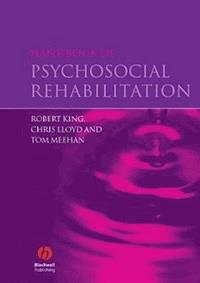

The Handbook of Psychosocial Rehabilitation is designed as a clinical handbook for practitioners in the field of mental health. It recognises the wide-ranging impact of mental illness and its ramifications on daily life. The book promotes a recovery model of psychosocial rehabilitation and aims to empower clinicians to engage their clients in tailored rehabilitation plans. The authors distil relevant evidence from the literature, but the focus is on the clinical setting. Coverage includes the service environment, assessment, maintaining recovery-focussed therapeutic relationships, the role of pharmacotherapy, intensive case management and vocational rehabilitation.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 478

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

© 2007 by R. King, C. Lloyd, T. Meehan and Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Blackwell Publishing editorial offices:

Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK

Tel: +44 (0)1865 776868

Blackwell Publishing Inc., 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

Tel: +1 781 388 8250

Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd, 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

Tel: +61 (0)3 8359 1011

The right of the Authors to be identified as the Authors of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

First published 2007 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd

ISBN: 978-14051-3308-1

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Handbook of psychosocial rehabilitation / Robert King, Chris Lloyd, Tom Meehan. p. ; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4051-3308-1 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-4051-3308-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Mentally ill–Rehabilitation.

2. Psychotherapy patients–Rehabilitation. 3. Community mental health services.

I. King, Robert, 1949– II. Lloyd, Chris, 1954– III. Meehan, Tom, 1957–

[DNLM: 1. Mental Disorders–rehabilitation. WM 400 H2358 2007]

RC439.5.H362 2007

616.89´14–dc22

2006021670

A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

Set in 10/12.5pt Sabon by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong

The publisher’s policy is to use permanent paper from mills that operate a sustainable forestry policy, and which has been manufactured from pulp processed using acid-free and elementary chlorine-free practices. Furthermore, the publisher ensures that the text paper and cover board used have met acceptable environmental accreditation standards.

For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: www.blackwellpublishing.com

CONTENTS

List of contributors

1 Key concepts and definitions

Overview of chapter

Recovery and rehabilitation

Multidisciplinary service delivery: the biopsychosocial model of mental health

Practitioner, clinician, case manager, mental health professional

Client and consumer/service user

Evidence based practice, efficacy and effectiveness

Conclusion

References

2 Major mental illness and its impact

Overview of chapter

The burden of mental illness

Treatment environment and service utilisation

Classification of mental illness

Symptoms and consequential disability in severe and chronic forms of mental illness

Impact of symptoms on client functioning

Secondary disability and handicap

Recovery patterns

Factors associated with better outcomes

Conclusions

References

3 Lived experience perspectives

Overview of chapter

Knowledge bases that inform ‘recovery’

Lived experience construct of recovery

Recovery is constantly active

Impacts of a mental illness

Hard work – the effort of recovering

A framework that supports individual recovery processes

A word on the elements of recovery

Whose responsibility is recovery? – the role of the ‘other’

References

4 The framework for psychosocial rehabilitation: bringing it into focus

Overview of chapter

Introduction

A framework for psychosocial rehabilitation in mental health

Does the use of different lenses result in conflicting perspectives?

Conclusion

References

5 Building and maintaining a recovery focused therapeutic relationship

Overview of chapter

Consumer perspectives on the therapeutic relationship

Components of therapeutic relationship

Therapeutic alliance

Therapeutic alliance and treatment outcomes

Practical considerations

Engagement

Maintenance of therapeutic alliance during treatment

Overcoming strains or ‘ruptures’ in the therapeutic alliance

Resolving alliance ruptures

Conclusion

References

6 Individual assessment and the development of a collaborative rehabilitation plan

Overview of chapter

Assessment of needs

Strengths approach to assessment

Standardised measures in assessment for psychosocial rehabilitation

What is assessed?

The assessment strategy

The rehabilitation plan

Conclusion

References

7 Integrating psychosocial rehabilitation and pharmacotherapy

Overview of chapter

Antipsychotic medications

Antidepressants

Value and limitations of medications in recovery from mental illness

Combining pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments

Using medication within a recovery framework

Optimising compliance/adherence

Working effectively with primary care clinicians/pharmacists

Conclusion

References

8 Family psychoeducation

Overview of chapter

Early approaches

What is psychoeducation?

Why has family psychoeducation become such a prominent approach to mental illness?

Confidentiality: a challenge in communication with families

Family psychoeducation: from interventions designed to reduce expressed emotion to problem solving in multiple family groups

Brief family psychoeducation

Conclusion

References

9 Intensive case management in psychosocial rehabilitation

Overview of chapter

Introduction

Models of case management

Standard case management models

Clinical case management

Intensive case management

Psychosocial rehabilitation in the context of case management

How effective is case management?

ACT versus standard case management or hospital based rehabilitation

Conclusion

References

10 Community participation

Overview of chapter

Deinstitutionalisation

Social exclusion

Service delivery utilising a recovery focus

Role of rehabilitation practitioners

Conclusion

References

11 Vocational rehabilitation

Overview of chapter

Why is vocational rehabilitation important?

Facilitating access to employment for people affected by mental illness

Vocational rehabilitation in practice

Conclusion

References

12 Mental illness and substance misuse

Overview of chapter

Impact of substance misuse

Dual diagnosis

Service provision

Identifying substance use and encouraging change in clients

Motivational interviewing

Assessment and treatment

Conclusion

References

Useful resources

Key assessment instrument references

13 Early intervention, relapse prevention and promotion of healthy lifestyles

Overview of chapter

Introduction

Rationale

Defining early psychosis

Key principles of intervention

Strategies for intervention

Family involvement

Psychotherapy

Psychoeducation

Group programmes

Intervention in prodromal psychosis

Does specialist intervention in early psychosis make a difference?

Conclusion

References

Useful resources

14 Service evaluation

Overview of chapter

Why evaluate services?

Quality assurance, evaluation, or research?

Evaluation – factors to consider

Ethical considerations

Evaluation: example from the field (Project 300)

Evaluation and clinical practice – bridging the gap

Conclusion

References

15 The wellbeing and professional development of the psychosocial rehabilitation practitioner

Overview of chapter

Conceptualising stress and burnout

Acute stress associated with critical incidents

Occupational stress and burnout

Managing acute and secondary traumatic stress

Managing occupational stress and burnout

Clinical supervision as a case study of response to occupational stress

Professional development

Conclusion

References

Useful resources

Index

LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS

Trevor Crowe

School of Psychology

University of Wollongong

Northfields Avenue

Wollongong NSW 2522

Australia

Frank Deane

School of Psychology

University of Wollongong

Northfields Avenue

Wollongong NSW 2522

Australia

Helen Glover

enLightened Consultants

PO Box 7361

Redland Bay 4165

Australia

Shane McCombes

Senior Mental Health Educator

‘Healthcall’ Queensland Division

Pacific Highway

Pymble NSW 2073

Australia

Lindsay Oades

School of Psychology

University of Wollongong

Northfields Avenue

Wollongong NSW 2522

Australia

Terry Stedman

Director of Clinical Services

The Park, Centre for Mental Health & University of Queensland

Locked Bag 500

Richlands QLD 4077

Australia

Chapter 1

KEY CONCEPTS AND DEFINITIONS

Robert King, Chris Lloyd and Tom Meehan

Overview of chapter

The purpose of this chapter is to identify and discuss some of the key terms and concepts that will be found throughout this handbook. The aim is to enable the reader to gain an understanding of how we are using certain terms and why we think that the concepts behind the terms are central to mental health practice. Part of the chapter is concerned not just with defining terms but also with enunciating the three core values inherent in contemporary rehabilitation that inform our thinking. These values are:

Rehabilitation takes place within the framework of a commitment to recovery

Rehabilitation takes place within a biopsychosocial framework, and

Rehabilitation takes place within the framework of evidence-based practice

The meaning of the core concepts of recovery, biopsychosocial, and evidence-based practice is set out here, together with a discussion of the implications of each value position for practice. The reasons why we have decided upon using the terms ‘practitioner’ and ‘client’, the two key people in the rehabilitation relationship, will be discussed.

Recovery and rehabilitation

Recovery

Recovery has become a core concept in contemporary mental health practice and has taken on some reasonably specific meaning, some of which departs from common usage. In mental health practice there are three dimensions of recovery – an objective dimension that best corresponds with common usage, a subjective dimension that is more specific to the mental health practice environment, and a service framework dimension that combines elements of both the objective and the subjective dimensions.

Recovery as an objective phenomenon

This kind of recovery implies a reduction in the objective indicators of illness and disability. It does not imply full remission of symptoms or the absence of any disability but rather objective evidence of change in this direction. By objective evidence we refer to a range of indicators such as whether or not a person continues to meet diagnostic criteria for a specified illness, scores on standardised measures of symptoms, social functioning or quality of life, changes in employment status or other objective indicators of social functioning, rates of hospital usage or usage of other kinds of clinical services, and dependence on social security. When we see evidence that a person is maintaining consistent positive progress on one or more of these indicators without evidence of reversal on others, we can say that there is objective evidence of recovery. These kinds of indicators are commonly used both to collect epidemiological data on recovery from mental illness (see Chapter 2) and to determine the evidence base for effectiveness of psychosocial rehabilitation programmes (see below and also Chapter 14).

Recovery as a subjective phenomenon

As a result of attention to the voices of people who have experienced mental illness, it has become clear that objective indicators of recovery do not always correspond with the subjective experience of recovery. The experience of mental illness is not just one of symptoms and disability but equally importantly one of major challenge to sense of self. Equally, recovery from mental illness is experienced not just in terms of symptoms and disability but also as a recovery of sense of self (Davidson & Strauss, 1992; Schiff, 2004). Recovery of sense of self and recovery with respect to symptoms and disability may not correspond. A person may continue to experience significant impairment as a result of symptoms and disability but may have a much stronger sense of self. Inversely, symptoms and disability may improve while sense of self remains weak. The mental health consumer movement has advocated for the subjective dimension of recovery to share equal importance with the objective dimension in the clinical environment (Deegan, 2003). This implies much closer attention to the psychological and spiritual wellbeing of the person with mental illness than is characteristic of the standard service environment. It also has implications for evaluation of the effectiveness of mental health services (Anthony et al., 2003; Frese et al., 2001). The subjective dimension of recovery is explored in depth in Chapter 3.

Recovery as a framework for services

Anthony (1993) called for recovery to be the ‘guiding vision’ for mental health services. He argued that practitioners can only assist people suffering from mental illness to achieve recovery if they both acknowledge the importance of the subjective dimension of recovery and if they actually believe in the possibility of recovery. This call for a change in service philosophy argued that traditional services, operating more within a medical model and focusing purely on objective indicators of recovery, were failing to instil and sustain the experience of hope that was central to the possibility of recovery. In other words, if practitioners are not themselves hopeful it is difficult for those who are looking to them to facilitate recovery to develop hope. In the absence of hope and a belief in the reality of recovery, services will focus on basic maintenance only and not provide any inspiration for people with mental illness to achieve and grow (Turner-Crowson & Wallcraft, 2002). Advocates for recovery as a framework for services have also looked to epidemiological data that show that recovery is a reality for many people with the most severe disorders even when objective indicators are used, and evidence that well-developed mental health services can contribute to rate of recovery (for example, DeSisto et al., 1995a, 1995b; Harrison et al., 2001; Harding, Brooks et al., 1987). Resnick et al. (2004) have suggested that the polarity between biomedical and recovery models may be unfounded, and that it is possible to provide treatment that is mutually reinforcing.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation refers broadly to restoration of functioning and is used widely in the field of health. Psychosocial rehabilitation refers more specifically to restoration of psychological and social functioning and is most frequently used in the context of mental illness. It is based on two core principles (Cnaan et al., 1988):

People are motivated to achieve independence and self confidence through mastery and competence

People are capable of learning and adapting to meet needs and achieve goals

Table 1.1 outlines some of the key features of psychosocial rehabilitation as set out by Cnaan et al. (1988, 1990). More recently, Corrigan (2003) has revisited Cnaan’s principles and provided systematisation of the rehabilitation process having reference to the goals, strategies, settings and roles that are involved.

In some contexts, the term rehabilitation is used interchangeably with recovery and can be an unintentional or incidental process. However, throughout this book, the term rehabilitation is reserved for application to a purposeful programme designed to facilitate recovery. This may be a self-help or peer support programme but often it will be a programme that involves a mental health practitioner. As it is used in this sense, rehabilitation differs from recovery. Whereas recovery may take place in the absence of any specific programme, rehabilitation always implies purpose and specific goals. Rehabilitation may focus on objective indicators of recovery such as symptoms or measures of social functioning. It may also focus on subjective recovery as in recovery of a sense of self or of a sense of purpose. Often it will focus on both, and the general philosophy of this book is that it will be most successful when both dimensions of recovery are taken into account, and when rehabilitation programmes are delivered within a recovery framework whereby the practitioner has a belief in the recovery of the person with mental illness, and with generating and maintaining hope.

Table 1.1 Principles of psychosocial rehabilitation

1.

All people have an under-utilised capacity, which should be developed

2.

All people can be equipped with skills (social, vocational, educational, interpersonal and others)

3.

People have the right and responsibility for self-determination

4.

Services should be provided in as normalised an environment as possible

5.

Assessment of needs and care is different for each individual

6.

Staff should be deeply committed

7.

Care is provided in an intimate environment without professional, authoritative shields and barriers

8.

Crisis intervention strategies are in place

9.

Environmental agencies and structures are available to provide support

10.

Changing the environment (educating community and restructuring environment to care for people with mental disability)

11.

No limits on participation

12.

Work centred process

13.

There is an emphasis on a social rather than a medical model of care

14.

Emphasis is on the client’s strengths rather than on pathologies

15.

Emphasis is on the here and now rather than on problems from the past

After Cnaan et al., 1988, 1990.

Multidisciplinary service delivery: the biopsychosocial model of mental health

This handbook is designed for multidisciplinary practitioners. What do we mean by multidisciplinary and what implications does this term have for psychosocial rehabilitation?

First, let us introduce a related concept: biopsychosocial. Biopsychosocial is a term that was introduced into the field of mental health practice (Engel, 1980; Freedman, 1995; Pilgrim, 2002) to draw attention to the implications of two key characteristics of mental illness:

Mental illness affects multiple domains or systems and not just one system. Specifically, the biological, psychological, and social systems of the person with mental illness are all likely to be implicated.

The three systems are interlinked. They do not operate in isolation from each other. Whatever happens in one system is likely to have implications for the other.

As Pilgrim (2002) pointed out, the holistic and humanistic premises of the biopsychosocial model have a long history in mental health care that predates the introduction of the term by Engel (1980).

A multidisciplinary approach to psychosocial rehabilitation means being able to think multisystemically. This includes being both aware and respectful of the possible contributions of other mental health practitioners who have specific expertise in one or other domains (Liberman et al., 2001). It also means having a capacity to facilitate access to services across different domains, and communicate with practitioners who have specialist skills in these different domains. In some situations it means working in a multidisciplinary team, whereby practitioners with different kinds of expertise routinely communicate and consult. However, multidisciplinary practice is more about the use of a biopsychosocial framework and development of an attitude to practice than the presence or absence of a team.

Practitioner, clinician, case manager, mental health professional

There is some variability in the term used to describe the person who is trying to facilitate the recovery process. We have decided to adopt the term practitioner throughout this book but terms such as clinician, case manager, and mental health professional could also be applicable. Practitioner is the term we have decided to use. The term is defined as ‘one who is engaged in the actual use of or exercise of any art or profession’. It implies both expertise and purpose in a designated field but is very broad with respect to field. Practitioner has an honourable history in the health sciences, being used to refer to medical and nursing practice, but is also applied much more broadly in the practice of a wide range of professions, trades and arts.

The term clinician was considered but rejected because it implies a clinical service environment. Psychosocial rehabilitation can be delivered in clinical environments as part of a mix of services that might include medication, psychotherapy, and even inpatient care. However, it can also be delivered in non-clinical community services that have no medical or other clinical components. The term clinician is therefore too narrow to accommodate the range of relationships we have in mind. We do not wish to exclude clinicians and, indeed we suspect that people who identify themselves as clinicians, whether nurses, psychologists, occupational therapists or even medical practitioners, will form a major group amongst our readers. We believe that this group can also identify as mental health practitioners or psychosocial rehabilitation practitioners.

The term case manager has a wide currency in mental health and has been used to refer to both clinical and non-clinical roles – even occasionally to provision of services by peers. However there are two problems with this term. These are best captured by the objection expressed by a person with mental illness at a conference: ‘I’m not a case and I don’t want to be managed’. It has the connotation of a bureaucratic rather than a personal relationship and it also has the connotation of control or at the very least responsibility that does not apply in many rehabilitation relationships. Some services are adopting the term ‘care coordinator’ as being somewhat less impersonal. However, like case manager, this term implies that clients cannot coordinate their own services. In some cases this will be a reasonable assumption and we have no objection to services using the term case management or care coordination. However, we think that there are many rehabilitation relationships that take place outside of this framework. Therefore, while many of our readers may be designated by their services as case managers, we hope they can equally see themselves as mental health practitioners.

Mental health professional is a broader term than clinician or case manager but may be narrower than practitioner. For some the term ‘professional’ implies membership of a recognised profession and evokes issues of registration or membership of a professional association. While we do not doubt that many if not most of our readers will identify themselves as professionals, we expect that there will be some people who find the term difficult to identify with. For example, some community organisations employ staff because they have life or work experience that equips them to work effectively in a psychosocial rehabilitation relationship with clients who have a mental illness. In some cases these staff will not possess qualifications that provide entry into any professional association or enable registration or certification. Such people are practitioners but not necessarily mental health professionals.

Client and consumer/service user

One of the more vexing issues in mental health practice is the proper designation for the person with mental illness who is working with a mental health practitioner. The most common terms are ‘client’ and ‘patient’. Both have drawn criticism. The term client has been criticised for evoking a different and more impersonal relationship – such as the relationship with a lawyer or a banker or accountant. It can also imply a very unequal level of expertise and a relationship in which the client is the passive recipient of information or advice or where the other person acts on behalf of the client. The term patient implies a more personal relationship but one that is even more unequal and in which the person with mental illness has a high degree of dependency. The term patient also evokes a medical model of care with focus on physical dimensions of mental illness but not on the social and psychological dimensions.

Two other terms have currency. The term ‘consumer’ or ‘service user’ is preferred by some service providers/consumers. These terms come from the broader consumer movement and imply that as a direct or indirect purchaser of services the person has rights and reasonable expectations concerning service quality. They are therefore relatively empowering compared with client or patient. However they suffer, even more than client, as a result of rendering the relationship impersonal and evoke analogies with purchasing a car or supermarket shopping. Some prefer the term ‘survivor’, which implies a degree of resilience in the face of the major challenges of the illness. Survivor is most popular with people who have been unhappy with mental health services. Such people often see themselves as having survived not only the ravages of the illness itself but also the mental health system.

The issue of terminology is so difficult that it is not uncommon to hear people say in exasperation, ‘I am not a patient or a client or a consumer or a survivor – I am a person’. This kind of statement suggests that none of the terms is really satisfactory and each carries with it the risk of depersonalising the relationship. However, rehabilitation implies a relationship that is specific in its purpose and the term ‘person’ is not adequate to convey the qualities of this relationship.

In an attempt to learn more about how people affected by mental illness saw their relationship with mental health professionals and, in particular, how they preferred to be seen, we conducted a survey in which people were asked which of several terms they most identified with (Lloyd et al., 2001). Overall, we found that client was the preferred term but that it was somewhat context specific. People in acute inpatient care were more likely to identify themselves as ‘patients’, whereas people in community or outpatient settings were more likely to identify as ‘clients’. In a similar study, McGuire-Snieckus et al. (2003) found that people surveyed in the UK identified with the term ‘patient’ when the context was seeing a general practitioner or psychiatrist and equally with the term ‘client’ or ‘patient’ when seeing non-medical mental health professionals. The terms ‘consumer’, ‘service user’ and ‘survivor’ were not favoured in either study. We think that the terms consumer and service user are probably best reserved for advocacy, service quality improvement and service management roles where the person is representing the wider group of mental health service consumers. They are less suitable for the rehabilitation relationship, which is necessarily a deeply personal one.

Taking into account all these consideration, while acknowledging the limitations of the term, we think that client is the least unsuitable term for application in the context of psychosocial rehabilitation. We are typically dealing with a community rather than an inpatient context where services are primarily provided by non-medical practitioners. The focus is on psychosocial functioning and experience rather than physical functioning and illness. Throughout the book you will find the term client used, rather than patient, consumer or service user.

Evidence based practice, efficacy and effectiveness

Evidence based practice (EBP) is a core value of contemporary psychosocial rehabilitation (Dixon & Goldman, 2004; Drake et al., 2001, 2003). It asserts that priority must be given to practices that are either known to contribute in a positive way to recovery or at least are reasonably likely to contribute to recovery. EBP is distinguished from practice by tradition, whereby rehabilitation practices are maintained because ‘this is what we have always done’. EBP emerged in part from a critical movement in medicine (Davidson et al., 2003; Liberati & Vineis, 2004; Sackett et al., 1996) that questioned the value of established procedures such as tonsillectomies and hysterectomies that were commonly believed to be helpful but had not been subjected to rigorous investigation. EBP has also been influenced by the ‘scientist–practitioner’ model (Chwalisz, 2003), which was developed within the profession of psychology. The scientist–practitioner employs an empirical scientist approach to practice, designing interventions based on the best possible information, measuring the impact of the interventions, and then modifying the interventions in response to information about their impact.

EBP operates from the premise that once an intervention has been demonstrated to be effective with a specific problem, it should be able to be implemented to good effect whenever that problem is present. However, practitioners should remain alert to the impact of the intervention and not simply assume it will be effective in every case. In this sense every practitioner within the EBP framework is also a scientist–practitioner, or in other words a consumer of research. EBP is developed through formal research and is disseminated through research reviews, practice guidelines and formal training. This handbook is designed to disseminate EBP.

In EBP, all evidence is not equal and there are established hierarchies of evidence (Trinder, 2000). These hierarchies provide a guide to the robustness of the evidence. At the bottom of the hierarchy are single case reports. These are better than no evidence but are weak for two reasons:

They may not be generalisable – what works for one person might not work for another. The single case-study may depend on highly individual characteristics of the client, the practitioner or their introduction and may not be replicable for other people or in other settings.

There may be no causal relationship between the intervention and the outcome – the change observed in a single case report may be attributed to the intervention when it was actually caused by something separate from the intervention.

Formal evaluation of interventions is designed to investigate these two issues – their generalisability and the causal relationship between intervention and outcome. Until this has been clearly established, the intervention has a weak evidence base. Near the top of the hierarchy are randomised controlled trials (RCTs). These are especially good at resolving the issue of causality. If we take a group of people who share a common problem and half are randomly allocated to receive an intervention and the other half either continues with usual care or gets a placebo intervention, then we are likely to attribute any difference between their outcomes to the effect of the intervention. If a series of RCTs with different researchers in different settings yield similar outcomes, the evidence is especially persuasive because both the causality of the intervention is established and the generalisability or robustness of the intervention is demonstrated.

Between the single case study and the many times replicated RCT are a range of evidence types that are located in the middle of the hierarchy. These include observational studies and longitudinal studies where generalisability may be reasonably well demonstrated and causality is likely but not highly likely as in the RCT.

Practitioners need to develop some basic skills to read and interpret research (Lloyd et al., 2004). There are many factors that impact on the relevance of research findings to clinical practice (Essock et al, 2003; Lloyd et al., 2004; Tanenbaum, 2003). These include:

The similarity of the research environment to the practice environment. This is sometimes referred to as the efficacy versus effectiveness issue. Research studies often use carefully selected study groups and deliver the intervention in atypical environments. In general, the effect of interventions in a research setting (efficacy) is usually greater than its effect in a practice setting (effectiveness). An intervention is not really evidence based for practice until it has demonstrated that it remains efficacious in a practice setting.

The nature of the comparison condition. Many interventions are better than nothing but the EBP practitioner really wants to know if they are better than what she or he is doing now. It may not make sense to change practice until it can be demonstrated that a new intervention is superior to what is often termed ‘usual care’, and not to no treatment at all.

The importance of fidelity and adherence to treatment protocols. Some forms of EBP appear to be sensitive to variations in implementation. If this is the case, the practitioner has to be sure that it is possible to implement the intervention exactly as specified.

Much of the existing research on EBP was conducted without an understanding of the recovery vision and implemented prior to the emergence of the recovery framework. This means that focus has mostly been on objective indicators of recovery and it is possible that some evidence based interventions are less effective if evaluated against recovery vision criteria.

Whenever possible, this handbook will alert you as to the state of the evidence with respect to the above issues. However, practitioners must be wary of excessive reliance on textbooks or published treatment guidelines. The evidence is constantly changing and being an evidence-based practitioner implies a commitment to remaining alert to developing the evidence base rather than assuming a static evidence base.

Conclusion

This chapter has introduced some of the core concepts that inform the approach taken throughout this handbook. These concepts are explored in relation to psychosocial rehabilitation whereby a recovery orientation, a biopsychosocial approach and evidence based practice constitute a values framework. We have briefly examined some of the terminology that is currently used in mental health service provision. The terms client and practitioner are preferred in the context of this handbook.

References

Anthony, W. (1993). Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 16, 15–16.

Anthony, W., Rogers, E., & Farkas, M. (2003). Research on evidence-based practices: Future directions in an era of recovery. Community Mental Health Journal, 39, 101–114.

Chwalisz, K. (2003). Evidence-based practice: A framework for twenty-first century scientist-practitioner training. The Counselling Psychologist, 31, 497–528.

Cnaan, R., Blankertz, L., Messinger, K.W., & Gardner, J. (1988). Psychosocial rehabilitation: Toward a definition. Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation, 11, 61–77.

Cnaan, R., Blankertz, L., Messinger, K.W., & Gardner, J. (1990). Experts’ assessment of psychosocial rehabilitation principles. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 13, 59–73.

Corrigan, P.W. (2003). Towards an integrated, structural model of psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 26, 346–358.

Davidson, K.W., Goldstein, M., Kaplan, R.M., Kaufmann, P.G., Knatterud, G.L., Orleans, C.T., Spring, B., Trudeau, K.J., & Whitlock, E.P. (2003). Evidence-based behavioral medicine: What is it and how do we achieve it? Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 26, 161–171.

Davidson. L., & Strauss, J.S. (1992). Sense of self in recovery from severe mental illness. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 65, 31–45.

Deegan, G. (2003). Discovering recovery. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 26, 368–376.

DeSisto, M., Harding, C., McCormick, R., Ashikaga, T., & Brooks, G. (1995a). The Maine and Vermont three-decade studies of serious mental illness I. Matched comparison of cross-sectional outcome. British Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 331–338.

DeSisto, M., Harding, C., McCormick, R., Ashikaga, T., & Brooks, G. (1995b). The Maine and Vermont three-decade studies of serious mental illness II. Longitudinal course comparisons. British Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 338–342.

Dixon, L., & Goldman, H. (2004). Forty years of progress in community mental health: The role of evidence-based practices. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 31, 381–392.

Drake, R., Goldman, H., Leff, H., Lehman, A., Dixon, L., Mueser, K., & Torrey, W. (2001). Implementing evidence-based practices in routine mental health service settings. Psychiatric Services, 52, 179–182.

Drake, R.E., Rosenberg, S.D., Teague, G.B., Bartels, S.J., & Torrey, W.C. (2003). Fundamental principles of evidence-based medicine applied to mental health care. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. Special Evidence-based Practices in Mental Health Care, 26, 811–820.

Engel, G.L. (1980). The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. American Journal of Psychiatry, 137, 535–544.

Essock, S., Goldman, H., Van Tosh, L., Anthony, W., Appell, C., Bond, G., Dixon, L., Dunakin, L., Ganju, V., Gorman, P., Ralph, R., Rapp, S., Teague, G., & Drake, R. (2003) Evidence-based practices: setting the context and responding to concerns. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 26, 919–938.

Freedman, A.M. (1995). The biopsychosocial paradigm and the future of psychiatry. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 36, 397–406.

Frese, F., Stanley, J., Kress, K., & Vogel-Scibilia, S. (2001). Integrating evidence-based practices and the recovery model. Psychiatric Services, 52, 1462–1468.

Harding, C., Brooks, G., Ashikaga, T., Strauss, J., & Brier, A. (1987). The Vermont longitudinal study of persons with severe mental illness, I. Methodology, study sample, and overall status 32 years later. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 718–726.

Harrison, G., Hopper, K., Craig, T., Laska, E., Siegel, C., Wanderling, J., Dube, K.C., Ganev, K., Giel, R., an der Heiden, W., Holmberg, S.K., Janca, A., Lee, P.W., Leon, C.A., Malhotra, S., Marsella, A.J., Nakane, Y., Sartorius, N., Shen, Y., Skoda, C., Thara, R., Tsirkin, S.J., Varma, V.K., Walsh, D., & Wiersma, D. (2001). Recovery from psychotic illness: A 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 178, 506–517.

Liberati, A., & Vineis, P. (2004). Introduction to the symposium: What evidence based medicine is and what it is not. Journal of Medical Ethics, 30, 120–121.

Liberman, R.P., Hilty, D.M., Drake, R.E., & Tsang, H.W. (2001). Requirements for multi-disciplinary teamwork in psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychiatric Services, 52, 1331–1342.

Lloyd, C., King, R., Bassett, H., Sandland, S., & Savige, G. (2001). Patient, client or consumer? A survey of preferred terms. Australasian Psychiatry, 321–324.

Lloyd, C., Bassett, H., & King, R. (2004). Occupational therapy and evidence-based practice in mental health. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 67, 83–88.

McGuire-Snieckus, R., McCabe, R., & Priebe, S. (2003). Patient, client or service user? A survey of patient preferences of dress and address of six mental health professions. Psychiatric Bulletin, 27, 305–308.

Pilgrim, D. (2002). The biopsychosocial model in Anglo-American psychiatry: Past, present and future? Journal of Mental Health, 11, 585–594.

Resnick, S., Rosenheck, & Lehman, A. (2004). An exploratory analysis of correlates of recovery. Psychiatric Services, 55, 540–547.

Sackett, D.L., Rosenberg, W.M.C., Muir-Gray, J.A., Haynes, R.B., & Richardson, W.S. (1996). Evidence-based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. British Medical Journal, 312, 71–72.

Schiff, A. (2004). Recovery and mental illness: Analysis and personal reflections. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 27, 212–218.

Tanenbaum, S. (2003). Evidence-based practice in mental health: Practical weaknesses meet political strengths. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 9, 287–301.

Trinder, L. (Ed.) with Reynolds S. (2000). Evidence-based practice: A critical appraisal. Oxford: Blackwell Science.

Turner-Crowson, J., & Wallcraft, J. (2002). The recovery vision for mental health services and research: A British perspective. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 25, 245–254.

Chapter 2

MAJOR MENTAL ILLNESS AND ITS IMPACT

Tom Meehan

Overview of chapter

This chapter reviews the major mental health conditions and discusses the disability associated with such conditions. Consideration is given to diagnostic systems, especially ICD-10 and characteristics of schizophrenia and severe affective disorder are identified. Factors that impact on recovery are examined and a case for the provision of rehabilitation programmes for people with severe disability is established. The focus is on severe mental illness (schizophrenia and more severe forms of mood disorder). These conditions often compromise people’s ability to live independent and productive lives and account for the bulk of people who need psychosocial rehabilitation interventions.

The burden of mental illness

Although mental illness is responsible for little more than one percent of deaths, it accounts for almost 11% of disease burden worldwide. Traditional approaches to the assessment of the disease burden used mortality (i.e. years lost through premature death) as the primary method of calculation. However, more recent approaches recognise the impact of disability associated with a given disease (i.e. years lived with a disability) and this is now considered in the assessment of burden. Together these two elements of burden are termed ‘Disability Adjusted Life Years Lost’ or DALYs (Murray & Lopes, 1996). Thus, one DALY represents one lost year of healthy life. Once the mortality and disability aspects of illness are combined into a single score, the magnitude of the burden associated with mental disorders becomes apparent. Five of the ten leading causes of disability worldwide in 2000 were psychiatric conditions: unipolar depression, alcohol use, bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia and obsessive–compulsive disorder (World Health Organization, 2002). By itself, unipolar depression was responsible for one in every ten years of life lived with a disability worldwide. Murray & Lopes (1996) suggest that by 2020, depression will follow ischaemic heart disease as the second greatest cause of disease burden. The relatively high burden associated with depression stems from a combination of its high prevalence, high impact on functioning, and early age of onset (Ustun et al., 2004).

Treatment environment and service utilisation

Up to the early 1950s, mental health care was carried out primarily in large institutions. These institutions were usually located on the edges of urban areas or out of public view in the country. Admission to the ‘asylum’ generally resulted in a life sentence, with little or no prospect of discharge. Although the institutions claimed total responsibility for the lives of those admitted, they provided little by way of therapy or rehabilitation. The majority of state institutions lacked medical supervision and provided nothing more than custodial care for the insane.

By the late 1950s, powerful social, medical, legal and economic factors turned the tide away from care in institutions to care in the community. It was postulated that community treatment would promote independence and result in secondary gains such as reintegration into a daily routine, preservation of the family unit and minimal disruptions to employment (Durham, 1989). In Australia, the number of long-stay beds at stand-alone hospitals decreased from 300 per 100 000 inhabitants in 1960 to 40 per 100 000 in 1990 (Whiteford, 1994). This decline in bed numbers has continued and a recent estimate suggests that there are now approximately 15 beds per 100 000 located in stand-alone psychiatric hospitals (Department of Health and Aging, 2003).

Although psychiatric hospitals were significantly reduced in size, the financial resources required to maintain them continued to escalate. Tension developed between psychiatric hospitals and the ‘new’ community services which competed for limited resources. Moreover, people with serious mental illness, particularly those with schizophrenia, showed little interest in keeping appointments and were frequently lost to the system. Large numbers of mentally ill people received no treatment and among those who did, the treatment they received was frequently inappropriate or inadequate (Kessler et al., 2005a).

It was recognised that improving outcomes for people with mental illness required more than the provision of mental health services (Whiteford, 1994). Effective and cooperative links between mental health, primary health care, e.g. general practitioners (GPs), and non-health sectors (such as housing, disability services, vocational and rehabilitation services, etc.), were seen as crucial. A recent review of service delivery in Australia highlighted the increasing role of GPs in the treatment of mental health conditions (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2005). Of those presenting to GPs with mental health problems, affective disorders were the most frequently treated condition (Table 2.1). As expected, schizophrenia was the most common condition treated by community mental health services. Taken together, these two disorders account for approximately 40% of all mental health conditions treated by GPs and 70% of those treated by community mental health services.

Table 2.1 Mental health related problems managed by general practitioners and community based mental health services in Australia (2003–2004)

Disorder

General practice(%)

Community mentalhealth services (%)

Mood (affective) disorders

33

24

Schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders

6

46

Neurotic, stress related somatoform disorders

23

9

Disorders due to psychoactive substance use

10

3

Behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances/physical factors

16

1

Other conditions

12

17

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2005.

Although schizophrenia has a lower prevalence than most other mental health conditions (less than 1% of the population), people with schizophrenia utilise approximately 40% of all mental health services. In contrast, major depressive disorder with a prevalence rate of around 6% accounts for 30% of service utilisation (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2005).

Classification of mental illness

Mental illness and mental disorder are terms commonly used to describe conditions that interfere with thought, emotion and/or behaviour. Mental illness is a general term used to describe a broad range of mental health problems including mental disorders. Mental disorder implies that a clinically recognisable set of symptoms and behaviours is present. Mental illness can also be classified as ‘psychotic’ or ‘non-psychotic’. People experiencing a psychotic (major) illness lose contact with reality and symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions are accepted as being real (e.g. the schizophrenias, major depression, bipolar disorder). Non-psychotic conditions on the other hand are less severe in the sense that the sufferer experiences less distortion of reality – hallucinations and delusions are absent. Anxiety states and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) are examples of neurotic/non-psychotic conditions.

Other ways of classifying mental health problems employ internationally recognised classification systems such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association (APA, 1994) or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) promoted by the World Health Organization (1992). ICD is currently used in approximately 100 countries around the world, and by the World Health Organization, which compiles international statistics on mortality and morbidity. While DSM continues to be the primary classification and diagnostic tool for psychiatric conditions in North America, ICD has become the coding system of choice in the UK (Hart, 2004) and more recently in Australia (Janca et al., 2001).

Symptoms and consequential disability in severe and chronic forms of mental illness

The symptoms of most mental disorders are clearly described in medical and nursing texts and therefore will not be discussed in detail here. In this text we are concerned with severe disorders that produce major and chronic functional impairment requiring psychosocial rehabilitation. Thus, a brief overview of the schizophrenias and the mood disorders will be provided to facilitate understanding of symptom patterns and their impact on functioning.

Schizophrenia and related disorders

Schizophrenia is the term frequently used to describe a range of related disorders with overlapping symptoms (e.g. schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder). The original name for the illness, ‘dementia praecox’, arose from the progressive deterioration in cognitive functioning (i.e. dementia) that accompanied the illness. The ‘schism’ between what is reality in one’s outer world and what is reality in one’s inner world gave rise to the term schizophrenia (‘split mind’). Schizophrenia has a number of subtypes, which are diagnosed on the basis of the most prominent symptoms present at the time of assessment.

Three phases of the illness have been identified, which include prodrome, active phase and residual phase. The prodrome is a period during which some signs and symptoms are evident but not of the intensity to warrant a diagnosis. The prodrome may be brief, with acute symptoms developing over weeks, or insidious, where symptoms develop over months or years (protracted prodrome). In 75% of cases, first admission is preceded by a prodromal phase of around five years with a psychotic ‘prophase’ of approximately one year (Hafner & der Heiden, 1997). The prodrome is followed by active phase symptoms, which are dominated by delusions, hallucinations, disorganised speech, bizarre behaviour and blunted affect. Once the active phase settles, the illness enters the residual phase. The features of this phase include social and occupational impairments, and abnormalities of cognition, emotion and communication. Rehabilitation efforts are usually introduced in the residual phase to offset the disability associated with the illness.

It is suggested that most of the impairment found in individuals with psychotic disorders results from alterations in neural functioning during prodrome (Larsen & Opsjordsmoen, 1996). This has shifted the focus of treatment to early identification and treatment of symptoms in people presenting with psychosis, especially first episode psychosis (McGorry et al., 2000). Untreated psychosis appears to have a noxious effect on the brain, leading to deterioration in cognition and social functioning over time (Addington et al., 2004).

Mood disorders

Depending on inclusion criteria, it is estimated that at least one in every ten individuals will suffer from depression during their lifetime (Kessler et al., 2005b). Like schizophrenia, depression is a general term used to describe a collection of conditions related to mood or affect (i.e. affective disorders). Major depression and bipolar affective disorder are two of the more serious conditions in this group.

Major depression

The lifetime prevalence of major (unipolar) depression is around 20% for women and 10% for men (Waraich et al., 2004). The gender difference is consistent across cultures and across countries. It is estimated that up to 60% of people will experience more than one episode and up to 20% of people will continue to be depressed 12 months post-diagnosis (Sargeant et al., 1990). Major depression among adolescents is frequently associated with antisocial behaviour and substance abuse, which makes diagnosis difficult. Anxiety is also found in about 70% of people with depression and is one of the most common psychiatric conditions (Goldberg, 1998). This is in keeping with the early theory put forward by Seligman (1973) which suggested that anxiety is the initial response to a stressful situation. This is slowly replaced by depression in people who feel unable to control the situation.

The essential features of major depression include a feeling of being down or sad, loss of pleasure or interest in activities, loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, inability to concentrate, changes in appetite and weight loss/gain. These symptoms usually impact on the individuals’ social and occupational functioning (Goldberg, 1998). In severe cases, psychotic symptoms such as hypochondriacal delusions are usually present, e.g. individuals may complain of having no intestines and therefore are unable to eat food. The most serious consequence of depression is suicide and about 15% of people with major depression will commit suicide (Patton et al., 1997). Depression and less severe ‘dysthamia’ are associated with increased utilisation of services and higher social morbidity.

Bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder is the term now used for what used to be called manic depressive psychosis. People with this form of depression alternate between severe depression (described above) and excitement/elation, hence the term ‘bipolar’. Normal mood is experienced in the period between episodes. Mania usually occurs prior to age 40 years and rarely after this. Onset is usually sudden and in the absence of treatment, symptoms usually persist for up to 6 months. During episodes of mania, thought processes are usually incoherent and the person may experience delusions, usually of the grandiose type. There is a decreased need for sleep, and pressure of speech, flight of ideas (moving quickly from one idea to another) may also be present. Excessive involvement in pleasurable activities with negative consequences is a major problem. Disinhibited behaviour and impaired judgement may result in unsound financial decisions, legal problems and damaged reputations. People with bipolar disorder are less likely to work (Zwerling et al., 2002) and tend to be over-represented in the lowest income strata (Kessler et al., 1997). A recent Australian study found that people with bipolar disorder were more disabled than subjects with major depression in terms of days out of role (Mitchell et al., 2004). In hypomania, a less severe form of mania, thought processes remain intact and major symptoms such as delusions are not present. Many people enjoy this hypomanic state as they tend to be more productive and may be reluctant to seek/adhere to treatment for this reason.

Impact of symptoms on client functioning

The symptoms of most psychiatric conditions cause a degree of distress but the impact is circumscribed and the person suffering the disorder leads a ‘normal’ life. This is true of many of the common anxiety disorders such as obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and panic disorder. However, the symptoms of conditions such as schizophrenia and the major mood disorders can have a significant impact on individual functioning. The symptoms of these conditions are frequently unrelenting, may be extremely distressing, and may impair basic cognitive functions such as attention and concentration.

In conditions such as schizophrenia, symptoms are frequently classified as either ‘positive’ or ‘negative’. This is an important dichotomy for treatment staff. The positive symptoms (hallucinations, delusions and disorders of thought) are usually the focus of clinical intervention and to a large extent, respond to antipsychotic medications. Negative symptoms (lack of motivation, blunted emotions, loss of drive, social withdrawal and inattention) are major determinants of disability (Carpenter, 1996) but unlike positive symptoms, they respond poorly to conventional antipsychotic medications. Indeed, it has been suggested that neuroleptic medications may exacerbate negative symptoms and give rise to the so called ‘neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome’ (NIDS), which includes apathy, slowing of thought processes and diminished capacity to experience pleasure. Emerging evidence suggests that atypical antipsychotics may be more effective in combating negative symptoms (Velligan et al., 2003).

Secondary disability and handicap

Primary psychopathology associated with psychotic conditions such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder tends to plateau and even cease following the active phase of the illness. However, the ‘secondary’ effects (e.g. isolation, self-neglect, withdrawal, etc.) continue to accumulate, and these tend to become the focus of rehabilitation efforts. Extrapyramidal side effects are a common cause of secondary negative symptoms. Individuals experiencing akinesia, for example, may present with decreased speech and decreased motivation. Positive symptoms (e.g. paranoid ideas about being watched) can also lead to secondary symptoms such as isolation. Some of the more prominent secondary symptoms are summarised in Table 2.2.

Although all of the secondary symptoms listed above are likely to impact on recovery, factors such as stigma, residual symptoms, self-neglect and loss of social supports are likely to present major barriers to recovery.

Table 2.2 Secondary symptoms and impact on client

Secondary symptom

Impact on client

Stigma

Isolation, loneliness, low self-esteem

Residual positive symptoms

Isolation, anxiety, distress

Self-neglect

Unable to care for oneself

Lack of insight

Loss of skills, withdrawal, neglect

Socialisation into patient role

Loss of hope, withdrawal

Inability to make and keep friends

Isolation, loneliness

Side effects of medications

Blunting of emotions

Stigma

Despite efforts to combat stigma, the negative effects of stigma continue to have a major impact on the individual and their recovery. Link and Phelan (2001) identified a number of mechanisms through which this can occur:

• Once identified as being mentally ill, society may continue to reject the person even when the symptoms have subsided.

• The trauma associated with past rejection may continue to impact on the present functioning of the individual.

• While the symptoms of the illness may have subsided, the individual may go on to internalise the rejection. The negative impact of this can continue even in the absence of the original rejection.

Residual symptoms

Although many of the symptoms of the illness respond to clinical interventions such as medications and, in the case of depression and anxiety, psychological treatments, some individuals continue to experience persistent symptoms. These uncontrolled symptoms, combined with the side effects of the medications, reinforce the perception that people with mental illness are different. Symptoms such as difficulty in thinking and delayed responding may be interpreted as dullness or low intelligence, and the symptoms of depression as laziness. While more recent medications tend to have a lower side effect profile (see Chapter 7), any visible indication of illness can hinder community acceptance and impede recovery.

Self-neglect

Although most clinicians can recognise and describe the features of an individual who self-neglects, the concept of self-neglect remains poorly understood among health professionals. Lauder and colleagues (2002) define self-neglect as ‘the failure to engage in those self-care actions necessary to maintain a socially acceptable standard of personal and household hygiene’ (p. 331). While there is insufficient evidence to support the existence of a discrete self-neglect syndrome, self-neglecting behaviour appears to be associated with mental illness. Cooney and Hamid (1995) suggest that up to 50% of all severe self-neglect cases have a mental illness.

The treatment of self-neglect poses a major challenge for the client and carers. Self-neglect can range from mild problems with hygiene to severe neglect that places the individual at risk of disease and even death. In cases of severe neglect, the need for intervention is rarely questioned. In less severe cases the need for intervention is widely debated among clinical staff and carers. There are those who believe that people with mental illness have rights and the freedom to live as they choose, even if this involves elements of self-neglect. There are also those who hold the view that self-neglect is a manifestation of deviant behaviour and that statutory control mechanisms are justified to compel unwilling individuals to acceptable community norms. Clearly, intervention is required when the behaviour places the client at risk. As noted by Lauder (1999), the level and type of intervention from staff will depend on whether the individual ‘cannot clean, will not clean, finds it difficult to clean or does not see the need for cleaning’.

Inability to make/keep friends – social isolation

The relationship between having a mental illness and social isolation is well established. Many people who develop psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia exhibit subtle abnormalities in attention and cognitive functioning in early childhood (Cornblatt & Keilp, 1994). These abnormalities tend to persist into adulthood and impact on the individual’s ability to develop social roles. Thus, social isolation is usually well established prior to the onset of the illness. This raises the question of whether social isolation is a cause or a consequence of mental illness. The positive symptoms of schizophrenia, for example, can interfere with the individual’s ability to cope with the demands of interpersonal interaction and the decoding of social communication. Consequently, many people with mental illness living in the community continue to live in an isolated ‘mental health world’ where the only people that visit them are paid to do so (i.e. mental health staff).

Recovery patterns

Views on the outcomes of mental disorders have changed radically in recent years. Findings from a number of studies over the past 40 years indicate that up to 70% of people demonstrate significant improvement in their condition (Table 2.3). Studies in both the United States and Europe involving more than 1300 people with schizophrenia found that 46% to 68% of people either improved or recovered significantly over the long term (Harding et al., 1992). Hegarty and colleagues (1994) conducted a meta-analysis of the available outcome studies and concluded that 50% of people with schizophrenia will improve and up to 20% will recover.

Taken together, these studies suggest that symptoms and functioning can improve even in individuals discharged from the ‘back-wards’ of psychiatric institutions (Davidson & McGlasham, 1997). These findings challenge the belief that conditions such as schizophrenia follow a course of progressive deterioration. However, despite these positive indications, a degree of caution is required when considering the outcomes of conditions such as schizophrenia. Geddes and colleagues (2000) found that despite the introduction of atypical antipsychotics, progress in the treatment of conditions such as schizophrenia is modest at best. A recent review found that less than 15% of people met criteria for ‘recovery’ at 5 years after a first episode of psychosis (Robinson et al., 2004).

Table 2.3 Outcome of follow-up studies of people with schizophrenia

The variation in the proportion of clients rated as being improved or recovered is likely to stem from the way in which recovery is defined. Some studies used standardised rating scales to assess outcomes, while others employed more subjective assessments such as ‘improved’ or ‘recovered’. Differences in the level of treatment/rehabilitation provided during the study period may also influence outcomes. For example, the clients followed up by Harding et al. (1987) were receiving intensive rehabilitation, which may have contributed to the better outcome reported.

In contrast to schizophrenia, which is likely to show some improvement over time, the course of recurrent mood disorders tends to have two outcomes: full recovery with no further episodes (approximately 50% of cases) or episodic recurrence with a trend towards increasing frequency of episodes with the passage of time (Kessing et al., 2004). Most people manage ordinary lives that are interrupted from time to time by periods of incapacity. However, this does not imply that the impact of the illness is less severe. The emerging view from follow-up studies is that individuals with acute bipolar disorder frequently respond slowly to modern treatments and continue to experience high levels of symptoms and disability. In people with bipolar disorder, depression appears to be strongly associated with ongoing disability and excess mortality through suicide (Thase & Sachs, 2000). While the course of affective disorders can be improved through the use of medication, non-compliance with treatment is a common problem, particularly in those with bipolar disorder.