Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

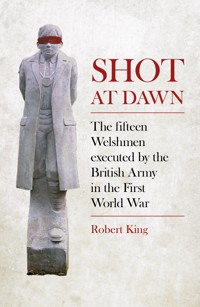

Thousands of British soldiers lie in cemeteries clustered around the battle sites of the First World War. Many of these volunteered for war, not realising trench warfare would be far from a grand adventure, nor that they would never return home. But not all of these were killed by the enemy. Over 3,000 soldiers were sentenced to death by Army Law, for desertion or other petty crimes, and more than 300 of these were blindfolded and shot by their own battalion. Many of the 'men' were still teenagers, and faced judgement in a time where shell shock was seen as an excuse for cowardice. They were branded traitors, their deaths covered up and their names forbidden from memorials. Only in 2006, nearly 100 years later, were they finally pardoned. Robert King was part of the campaign to pardon these forgotten men. Here he touches on the lives of fifteen Welshmen history has tried to ignore, and explores what it really meant to be led out and shot at dawn.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 207

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated to John Hipkin, who campaigned resolutely for a blanket pardon to be granted to the 306 soldiers who were shot at dawn by the authority of the Army Act during the Great War; and to the late Ernest Thurtle MP, whose resolve never swayed in his aim to achieve some degree of justice for them; to Andrew Mackinlay; and to the Right Hon. Des Browne, who brought the campaign to fruition.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to the following for helping in the making of this book: Darren Nichols, who has driven me hundreds of miles during the research; the Right Hon. Peter Hain MP, who has kindly written the foreword; Glyn Davies; Martin King; Richard Dyer; Brian Lee; Brian Baker; Lolita McAllister; Derek Vaughan MEP; Dr Paul Davies; Gareth Mathias; Barrie Flint, for drawing the maps; Daniel Smith; the Royal British Legion; the National Memorial Arboretum; Public Record Office; the Imperial War Museum; Leeds University; the Whitehall Library; Ministry of Defence; Declan Flynn and Naomi Reynolds of The History Press; and to my wife, Joy, for all her support.

Contents

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Rt Hon. Peter Hain, MP for Neath

Preface

Executions of Welsh Soldiers and Those Who Served in a Welsh Regiment in Date Order

Quotations

1

The Months Leading Up to the War

2

The King’s Shilling

3

Executed for Leaving His Post

4

Executed for Desertion

5

The Edwin Dyett Case

6

Executed for Committing Murder

7

Granting Posthumous Pardons to the 306 Executed Soldiers

8

The Firing Party

9

The Following Years

Executed Soldiers in Regimental Order

Burial Places or Commemorations of the Executed Soldiers

Bibliography

Copyright

Foreword

When Robert King asked me in 2006 to support a proposal in the House of Commons to grant a blanket pardon to those soldiers who were shot at dawn in the Great War, I was pleased to do so.

The terrible injustice suffered by 306 British men executed under the Army Act has been like a deep festering sore. Their ‘offence’ was quite likely to be suffering from shell shock – now called ‘post-traumatic stress syndrome’. Through no fault of their own they downed arms and could not serve, so breaching the regulations stipulated by the Army Act. The Shot at Dawn Campaign struggled for years to get recognition and pardons, which were finally granted by the government in which I served in 2006. They were victims of war rather than failures at war.

In the years following the First World War, their cause was raised with great passion in the House: the Labour MP Ernest Thurtle being one of the first to do so, in the early 1920s. He argued that the executed soldiers should be laid to rest in graves alongside those men who fell in action, after responding to a petition submitted by a soldier who felt that they should be honoured in the same way.

Thurtle was successful, and the men who died whilst facing the firing squad were laid to rest with the millions in the impeccably kept cemeteries in Belgium and Northern France.

After Thurtle’s time in Parliament, a pardon was raised on a number of occasions until it was finally achieved. But Robert King is not judgmental about the army. The Great War was a bloody, vicious conflict – arguably the worst in history for the sheer scale of casualties: men almost wantonly thrown into action and to their deaths, forced to run ‘over the top’ to a fusillade of fire and shells amidst the mud and the hideous, pounding chaos. Everyone was under unspeakable pressure as all hell broke loose and they witnessed the carnage, the ugly haunting stench of death everywhere. The officers at the time were adhering to the rules and regulations of the Army Act. Only a shade more than 10 per cent were shot, the rest suffering lesser punishments, though still with the stain of being cowards on their record.

The fact that many of the trial papers were destroyed after the Second World War was used as an excuse for why the subject should not be taken further.

But the Shot at Dawn Campaign persisted nevertheless. The Royal British Legion favoured a blanket pardon with the exception of those soldiers who had been executed for murder. And when it was brought to my attention that a man from my own constituency of Neath had faced the firing squad, my interest was intensified.

Many had no ‘prisoner’s friend’ in support and were not eloquent enough to defend themselves: many were shot as an example to others.

It is important that their stories are told and that their names should be added to the war memorials up and down the country. In very recent times, members of the Campaign have been allowed to march in the parade through London on Armistice Day. I urge anyone who has not visited the National Memorial Arboretum in Litchfield, Staffordshire, to do so and see the Shot at Dawn Memorial and take note of the very young ages of those men who seem to have cracked under the fearsome pressure and were executed for it.

Robert is to be commended for focusing upon the Welsh soldiers whose stories have not been told and whose memory we salute through this book.

The Rt Hon. Peter Hain

MP for Neath, former Secretary of State for Wales

Ynysygerwn, Neath

January 2014

Preface

My interest in the plight of those unfortunate men who suffered the fate, under the authority of Army Act, of being shot at dawn during the Great War, was ignited when I reviewed the Julian Putkowski/Julian Sykes book, Shot at Dawn, in 1989. Absolute ignorance had prevailed in my knowledge in respect of punishments doled out to those who transgressed against the British Army’s rules before I was sent the book by its publisher, Leo Cooper. I was familiar with the phrase ‘shot at dawn’ – it was used often by people in authority, particularly in the early years of the 1960s (by authority I mean those who were training and educating young people in that decade). I worked then in the horse-racing industry in Herefordshire and my employer was Peter Ransom who would, when I failed to muck out stables efficiently or fell off a horse, issue the threat: ‘You’ll be shot at dawn’. The real meaning passed me by with the process of growing up, but thirty years on it took on a dark shroud: the phrase has haunted the families of the men who were marched out of a building on the Western Front just as dawn was breaking across the French or Belgium landscapes. They were to be faced with a firing squad, usually consisting of men from the unfortunate’s own battalion, literally ‘blindfolded and alone’ – often having been convicted with no mitigation submitted.

I admit I became incensed with what I considered to be an injustice and started to write letters to support the loosely aligned campaign started by John Hipkin, hearing about and understanding the immense amount of work carried out in Parliament and beyond over many, many years by the Labour MPs Ernest Thurtle and Andrew Mackinlay, to secure a blanket pardon for the 306 British and allied soldiers who had been executed.

Then my attention focused on those Welshmen who had been regulars, volunteers or conscripts and then faced a firing squad for committing one of the variety of offences, when, either through in some cases alcoholic inebriation or shell shock (now called post-traumatic stress syndrome). There were fifteen of them: four were convicted of murder, ten for desertion and one for leaving his post. Those men had not been specifically documented in a Welsh context: details of those from England, Scotland, Ireland and other allied countries had been considered, those from Welsh Regiments had not.

It can be very difficult to identify soldiers who served with different regiments – often across the English/Welsh divide. George Povey, for instance, was from Flintshire in Wales but served in the Cheshire Regiment, and a number of Englishmen fought with Welsh regiments. This crossover has been researched as thoroughly as possible but at times it has proved impossible to identify where soldiers originally came from and some may have been missed.

Other documents generally say that of the 306 men, fifteen were Welsh and my research supports those findings.

Executions of Welsh Soldiers and Those who Served in a Welsh Regiment in Date Order

Date of Execution

Service Number

Name

Age

Battalion

Crime

11.2.1915

19459

Private George Povey

23

1/Cheshire

Leaving his post

15.2.1915

12942

Lance Corporal William Price

41

2/Welsh Regiment

Murder

15.2.1915

11967

Private Richard Morgan

32

2/Welsh Regiment

Murder

22.4.1915

10958

Private Major Penn

21

1/RWF

Desertion

22.4.1915

10853

Private Anthony Troughton

22

1/RWF

Desertion

15.11.1915

15437

Private Charles Knight

28

10/RW

Murder

7.2.1916

10874

Private James Carr

21

2/ Welsh Regiment

Desertion

30.4.1916

1/15134

Private Anthony O’Neill

*

1/SWB

Desertion

20.5.1916

12727

Private J. Thomas

44

2/Welsh Regiment

Desertion

5.1.1917

**

Sub-lieutenant Edwin Dyett Nelson

21

Bat. RND

Desertion

15.5.1917

8139

Private George Watkins

31

13/Welsh Regiment

Desertion

25.10.1917

15954

Private William Jones

*

9/RWF

Desertion

22.11.1917

11490

Private Henry Rigby

21

10/SWB

Desertion

10.5.1918

36224

Private James Skone

39

2/Welsh Regiment

Murder

10.8.1918

44174

Private William Scholes

25

2/SWB

Desertion

* In the cases of Private Anthony O’Neill and Private William Jones, their ages cannot be ascertained. It is believed they were both under 18 years.

** As Dyett was seconded into the army from the navy, he was still a member of the Nelson Battalion and so did not carry an army number.

Quotations

The following quotations serve to illustrate the attitude and feeling regarding executions carried out under the authority of the Army Act during the Great War.

Arthur Page describes the conditions of a typical general – or field – court martial. During the war these were held in France in a Nissen hut or a similar structure:

A table with a blanket over it, and some upturned sugar boxes usually did service for court equipment … I wish I could portray the scene as the drama unfolds. The dim light of a few spluttering candles throwing into relief the forms of the accused and his escort; the tired and drawn faces of the witnesses under their tin helmets; and the accused himself, apparently taking only a languid interest in the evidence as it accumulates against him.1

Percy Winfield describes the different treatment of officers to rankers:

The accused, if an officer, is allowed a seat; if of any other rank, only when the court think proper. It is hard to see how discipline could be injured if this was made a matter of right for all ranks.2

Lord Moran on the effects of shell shock:

Courage is will-power, whereof no man has an unlimited stock; and when in war it is used up, he is finished … His will is perhaps almost destroyed by intensive shelling, or by a bloody battle, or it is gradually used up by monotony, by exposure, by the loss of support of the staunchest spirits on whom he had come to depend, by physical exhaustion, by a wrong attitude to danger, to casualties, to war, to death itself.3

Edwin Vaughan on the battlefield:

From the darkness on all sides came the groans and wails of wounded men; faint, long sobbing moans of agony, and despairing shrieks. It was only too obvious that dozens of men with serious wounds must have crawled for safety into new shell holes, and now the water was rising about them and, powerless to move, they were slowly drowning.4

Charles Myers on the attitude to shell shock:

[He was] a very young soldier charged with desertion, who had been sent down to Boulogne for a report on his responsibility. He was so deficient in intelligence that he did not in the least realize the seriousness of his position. My only course, I thought, was to have him sent home, labelled ‘insane’ and the sequel was that he was returned to France with a report saying that no signs of insanity were discoverable in him.5

Edwin Dyett’s reputed last words when tied to the firing post, naturally fearing the coupe de grâce:

For God’s sake, shoot straight.6

Philip Gibb, a press correspondent, writes from the front in 1917:

… about a young officer, sentenced to death for cowardice (there were quite a number of lads like that). He was blindfolded by a gas mask fixed on the wrong way round, and pinioned, and tied to a post. The firing party lost their nerve and their shots were wild. The boy was only wounded, and screamed in his mask, and the A.P.M. had to shoot him twice with his revolver before he died.7

Leon Wolff quoting Philip Gibb on Flanders Fields:

And he continues to say that he encountered more and more deadly depression in the ranks among men who could see no future except more bloodshed. They feared what was to come, they cursed the luck that had brought them to Flanders while other more fortunate fellows were in Palestine, on battle cruisers in the Atlantic, at desks in London, playing at war in Greece, counting boots and cartridge cases at French ports, or a hundred other cushy places; and above all they hated the Salient with a despair reflected even in the place-names: Suicide Corner, Dead Dog Farm, Idiot Crossroads, Stinking Farm, Dead Horse Corner, Shelltrap Barn, Hellfire Crossroads, Jerk House, Vampire Point.

The scene in no man’s land during those final days of September was indeed a chilling one.8

Notes

1In Flanders Fields, Leon Wolff, p.153

2For the Sake of Example, Anthony Babington, p.121

3Blindfold and Alone, Cathryn Corns & John Hughes-Wilson

4In Flanders Fields, Leon Wolff, p.157

5Blindfold and Alone, Cathryn Corns & John Hughes-Wilson, p.75

6For God’s Sake Shoot Straight, Leon Sellers

7In Flanders Fields, Leon Wolff, p.153

8In Flanders Fields, Leon Wolff, p.154

Chapter One

The Months Leading Up To The War

The census figures for Wales in 1911 record a population of 2.4 million. The vast majority of the male population would have been employed in heavy industry, including agriculture. When war was declared in 1914, the government launched a patriotic plea asking for volunteers – usually called Kitchener Volunteers – to go to war for king and country. There was no conscription until 1917.

Seemingly bent on conflict, Germany had seriously remilitarised its army during the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II and started to gather its forces on the border with Belgium. Observing nations concluded that an invasion was imminent, despite Belgium being protected by a guarantee of neutrality. The British Prime Minister, H.H. Asquith, instructed the Foreign Secretary, Edward Grey, to issue an ultimatum: if Germany did not give Belgium an assurance of safety then Britain would intervene on Belgium’s side and war would be declared. At that time, the British Empire was still a respected force in the world.

Edward Grey’s missive stated that the deadline for this ‘assurance of safety’ would expire at 11 p.m. on 4 August 1914 which, records tell us, was a hot Bank Holiday weekend.No assurance was received from Germany, so Britain declared war and the bloody conflict began.

In Wales, 275,000 men signed up during the four years of war, including those conscripted after 1917. Of these, 35,000 were killed and many more were physically or mentally disabled, and left with little or no support.

David Lloyd George was keen to see men from Wales offering themselves as soldiers. To encourage friends to join in groups, Pals Battalions were established, which kept men from the same area together. However, this meant that they also died together – thus the large number of names on war memorials that populate almost every village. This idea was not propagated during the Second World War, when efforts were made for fighting men from same area to be kept apart, particularly if they were related.

With patriotic fervour sweeping the whole of Britain in the days and weeks following the declaration of war, men in their thousands volunteered. The idea that it would all be over by Christmas was bandied about and it was seen as an adventure, an attractive change from the norm. The actual realities of what they were signing up to came later, by which point there was no backing out of the commitment.

In Wales the majority of the male working population was employed in coal mines, quarries and agriculture. The wages were poor and living conditions were sparse, and so many young men willingly took the king’s shilling. Women took over many of the duties previously performed by the menfolk and children were encouraged to help the war effort by collecting conkers.

There was considerable excitement for those queued up at the recruitment offices. It was difficult to resist the accusing finger pointing out from the War Office posters, which proclaimed ‘Your Country Needs You’, or to ignore the undercurrent of encouraging young women to present those men still not in khaki with a white feather – the symbol of a coward. The pressure was extreme, as was described by Private Rhys Davies of Carmarthen. I spoke with Mr Davies in 1973:

My brother, Gareth, had signed up immediately when they asked for volunteers. He was four years older than me and couldn’t wait to go. We were both farm labourers working on different farms just outside the town. I remember Gareth saying when he told my mother he was going that he’d been to Swansea once, now he had the chance to go overseas. I was a bit jealous; although I looked older than my seventeen years I was resigned to wait. That was until I was walking in the town one night and this girl put a white feather into the top pocket of my coat.

‘A Welsh coward,’ she said. She was with five other girls who all giggled and made fun of me. I went bright red with embarrassment and stuttered I’m only seventeen.

‘That’s what they all say,’ she added and tried to give me another feather. She must have had a load of them in her handbag.

I was shaking with temper, turned and ran home. That white feather business was evil.

Anyway, the following day was the market and I knew I’d be able to have an hour off but I told no one what I was going to do.

When I got to the recruiting office there was a queue, about five or six of us. I knew a couple who had been friends of my brother but no one said anything. I think everyone was a little nervous or so excited they couldn’t talk.

The sergeant called my name and took details. I told him I was born in 1897; it was a lie, I was born in 1898. Then a doctor examined me and that was it. I was Private Rhys Davies.

I hurried back to the market and helped my employer to take some sheep home then I told him that I had joined the army and wouldn’t be working at the farm again. He went quiet. Then, completely out of character he said: ‘Good boy,’ and he gave me the money I was owed plus a ten shilling note. I was shocked at that and gave the ten bob to my mam.

It was those girls and the white feather that done it.9

Private Bryn Thomas from Tonypandy explained to me in the late 1960s that he was 28 and home on hospital leave in November 1915, when he was subjected to the humiliation of having a white feather handed to him ‘by a woman old enough to be my mother’:

I joined the army in 1912 to do something different really. I’d worked in the pits for a couple of years and got danted with it so I signed on.

When the war broke out then I found myself in Ypres, first off digging trenches. And then as the weather turned and things started getting nasty with the Germans those trenches got wetter and wetter, muddier and muddier until even our bolt holes got uncomfortable.

One night I was huddled deep in my hole, trying to snuggle into my clothes to keep warm, although they were lice ridden you get used to it, when I got a bloody rat bite on my leg. It pinched so much that I put my hand down straight away and caught the bloody thing and squeezed the life out of it. Working in the mines an old collier had once told me that a female rat’s bite is worse that a male’s so I turned it up and checked what it was. It was a male. But the wound swelled up and I was sent to the dressing station. From there they sent me home for a couple of weeks to give it time to heal. It was nice to get home.

Some soldiers liked to keep the uniform on even when on leave. I didn’t, soon as I got in to the house it was a hot bath in front of the fire and my own clothes.

I went down to Pontypridd to see my uncle a few days later and walking to a pub this woman stopped me and said I should be ashamed that I wasn’t at the front. I was shocked at this total stranger and then she gave me a feather. Uncle was in a temper. He ripped it from me and argued with her. A few people had stopped at the raised voices. ‘The man’s a regular,’ he shouted and threw it on the ground. ‘Come on, Private,’ he said, ‘a pint, enough of this nonsense.’ The woman, red faced, hurried away.10

Private Colin Phillips from Ruthin related his experience with a stoic nature when he agreed to talk to me in 1974:

I’d survived the Battle of Mametz Wood so anything anyone ever said to me after that didn’t matter much. Yes, a man, a minster of religion in fact, challenged me when I was on a leave. I was in my civilian clothes and he came on to me asking me if I felt ashamed. I knew what he meant and I treated him with distain. I didn’t say anything. I just looked at him with contempt. His white dog collar glistening, clean. I thought of the filth and carnage I’d been through and walked away. I never cared much for religion or anything after that. I even struggled with it when attending funerals in later years. I shouldn’t consider them all like that man who condemned me without knowledge. But there you are, as my mother always said, there’s good and bad wherever you look, everywhere.11

The above examples illustrate the emotional pressure placed on young men. The white feather syndrome was encouraged by government ministers to leave the public in no doubt that young men not in uniform were to be branded cowards.

In Wales, as in other parts of Great Britain, the conditions for most working-class men were very poor. In South Wales the mining industry was the major employer – a dangerous occupation which little changed after the Great War. The years between 1894 and 1914 recorded 1,275 fatalities in the South Wales coalfield. A conservative figure, it does not feature smaller incidents where only one or two miners lost their lives. The outbreak of war came a little under a year after the disaster at the Universal Colliery in Senghenydd on 14 October 1913 in which over 400 miners died, so it is unsurprising that joining the army was attractive; although miners worked in an exempt industry they volunteered in their thousands. They were sought by the Ministry of War because of their ability to dig tunnels in a safe and methodical manner, and the tunneling under no-man’s-land towards the German lines was principally carried out by those miners with coal-mining experience. Many would have been from South Wales.

Quarry workers in North Wales endured equally appalling and dangerous conditions and farmhands toiled in humbling and exhausting circumstances. Altogether, 275,000 men either volunteered or were conscripted from Wales in the First World War. Of these, 35,000 lost their lives on the Western Front, with fifteen men being shot at dawn following court martial. Four were members of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers; three belonged to the South Wales Borderers; six in the Welsh Regiment; one in the Cheshire Regiment; and one, an officer, in the Royal Naval Division. Two Welsh regiments had no members executed: the Monmouthshire and the Welsh Guards.

The figures for British soldiers from the Home Nations who faced a firing squad (allowing for those who served in another country’s regiment) were: 24 Irishmen, 43 Scotsmen and 209 Englishmen.