3,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

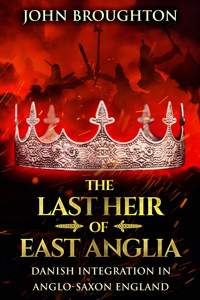

December, AD 902. King Æthelwold of East Anglia falls in battle, leaving behind a kingdom—and a daughter.

Elinor is crowned queen in a world where women rule only by extraordinary strength or divine destiny. Bound by duty and driven by a longing for peace, she weds a Danish chieftain in a bold bid to unite two warring peoples.

But unity comes at a cost. Elinor suffers loss upon loss—of children, of love, of the simplicity of youth. After bonding with Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians, Elinor must confront Viking raiders, broker peace, and build a new foundation for a fractured land.

A sweeping historical adventure, THE LAST HEIR OF EAST ANGLIA is a story of friendship and the power of one woman to reshape a kingdom.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

The Last Heir of East Anglia

DANISH INTEGRATION IN ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND

JOHN BROUGHTON

Contents

Author’s Note

Author’s Premise

1. Cooling, Kent, 902 AD

2. Theodford, Kingdom of East Anglia, early 902 AD

3. Theodford, May 902 AD

4. The East Anglian and Mercian borderlands, May 902 AD

5. Theodford, May 902 AD

6. Tameweorth and Theodford, late May 902 AD

7. Kingdom of East Anglia 2nd June 902 – 16th April 903 AD

8. Beodricesworth, May 31 904 AD

9. Rendlæsham, Tuesday 29 April 904 AD

10. Exning to Huntandun, 29 May – 1 June 904 AD

11. Rendlæsham, Friday 1–Tuesday 5 June, 903 AD

12. East Anglia and across Mercia to Tameweorth, September – October 904 AD

13. Rendlæsham and Filebi, East Anglia, autumn 905 AD

14. Rendlæsham and Caestre, May 22 – June 907 AD

15. Northwards into Northumbria, June 907 AD

16. Northumbria, early June, 907 AD

17. Rendlæsham and Hitchingford, Hertfordshire, June 907 AD

18. Tameweorth, Mercia and Bardney, Lindsey, spring 909 AD

19. Rendlæsham and Tameweorth, July, 910 – March, 911 AD

20. Rendlæsham, July 911 AD

21. April 913 AD

22. Rendlæsham to Northwic, April, 915 AD and Caestre, June 915 AD

23. Brecknock, Brycheiniog, Wales, early June 916 AD

24. Rendlæsham and Deoraby, July 917 AD

25. Deoraby and Rendlæsham, July 917 AD

26. Rendlæsham and Barking Abbey, East Anglia, 918 AD

27. Barking Abbey, and Rendlæsham East Anglia, 919 AD

About the Author

Copyright © 2025 John Broughton

Layout design and Copyright © 2025 by Next Chapter

Published 2025 by Next Chapter

Cover art by Charlyn Llanos

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author’s permission.

Author’s Note

This novel is written in English and been thoroughly checked. There are no typos or presumed misspellings. Please bear in mind that it is not written in (US) English.

Thank you,

JB.

Author’s Premise

The Last Heir of East Anglia is a historical fantasy novel and, as such, makes only a slight claim to historical accuracy, mostly in terms of backdrop. The main character, Elinor, is a figment of the author’s imagination. There is no evidence that Æthelwold had a daughter. The character was born of the desire to write a female protagonist similar to and entwined with the very real Aethelflaed, the Lady of Mercia, who, with her, could encapsulate these three themes:

There is also much controversy about the very existence of Guthrum II, but it seems fitting that he should play the role I have chosen for him, given the fictional nature of Elinor.

Also, I have used a sprinkling of Saxon place names to add a period feel. However, I did not wish to overdo this, so the reader will find exceptions. There are footnotes with the present-day place names.

Finally, it is the author’s aim to provide general readers with a feel for the Anglo-Saxon–Viking period using literary licence without overtaxing them with a suffocating historical straitjacket. I hope that I have succeeded in this unpretentious aim and that you will enjoy the novel.

Cooling, Kent, 902 AD

My name is Elinor and my father—well, that’s a moot point—I suppose that I had two. My natural father was Æthelwold and I can’t hate him because he sent me away for my own safety. Some people think that he was a coward and a traitor, whereas others maintain that he was simply ill-starred. He had a strong claim to be the true king of England, but his forebear died when he was but an infant and, of course, that was not his fault. Nor was it his fault that the Danes invaded the land and washed over it like a great incoming tide while he was still a child.

My other father was the Ealdorman of Kent, Sigebert, who was good enough to take me into his family for my protection. Thus, my best friend, whom I called sister, although she was not, was Eadgifu, who later married my birth father’s enemy, Edward, known as the Elder. I loved my time in Kent and lacked for nothing. Eadgifu was a sweet child and I learnt much from her about kindness and patience, although I shall never be as saintly as she. I swear I gained experience in diplomacy and strategy from listening to her dealings with her father’s counsellors in troubled times, although some of my skills were decidedly inborn.

You really should understand the tumult and uncertainty of those days before you assess my achievements and failures, my triumphs and setbacks. The premise you should know is that this was the late 9th century, a time when the Viking Age loomed heavily over all of England. The kingdom of East Anglia, my father’s realm, seemed on the brink of collapse, teetering near the abyss. He, as I have mentioned before, was Æthelwold, now an ageing and wiser man, who suddenly remembered he had a long-lost daughter—me, Elinor. Hidden away to protect me during such a turbulent chapter of the kingdom’s history. I was raised in a remote village in Kent called Cooling. Let’s say it was a stroke of presentiment, for he had no sons, and the shadow of his end drew near. Could his daughter, whom he had forsaken to assure her safety, return to unite the fractured nobility of East Anglia, to heal its rifts where he had failed? This question tormented him. Could she do what he had not? Could one girl, a stranger to power and battle, learn the politics and warfare necessary to save all that he held dear? He knew that I awaited him—grew to girlhood and beyond in Cooling, readying myself for this very moment, anxious and expectant, hoping not to be forgotten after all. I matured knowing the day would come when I would be called back to serve, but I was never sure when it would come. I could feel the uncertainty like a fever, burning and never abating. I’m not sure if I was more eager or afraid. I awaited his summons.

Having said that, did I share his vision of kingship? I did not. My heart was bound to my beloved Eadgifu, and betraying her was unthinkable. She was the third wife of my father’s nemesis, the man my father believed had unjustly assumed the throne meant for him. Edward, the son of the legendary King Alfred, was revered by all as a hero. Alfred had seized the throne of Wessex when my father, but a mere infant, was unable to defend it against the relentless Danish invaders who had swept through Mercia and into Wessex.

Alfred had turned the tide, famously defeating the invaders at the Battle of Edington. Yet, after Alfred’s death, my father had a stronger claim than Alfred’s firstborn, Edward. However, his ambitions were thwarted when Edward, mustering a formidable host, camped his army on an ancient hillfort near Wimborne. My father, in a bid to strengthen his position, had journeyed there to seize a noble nun, hoping her status would bolster his position. But he found himself unable to gather a force strong enough to challenge Edward’s might. Undefeated but humiliated, he fled to Northumbria, where he was declared king—a consolation that could never erase the sting of his lost birthright. I’m convinced that he saw Northumbria as a mere stepping stone.

I must be mindful not to rush ahead or you will miss the twists and turns that define my story. Instead, I will entrust the telling to someone much better suited for the task. The account of my life will be passed to my devoted chronicler, Wihtburh, whose noble lineage and steady hand with the quill make her uniquely qualified to bring light to these turbulent years. Raised with the finest education at the Abbey of Ely, she studied among scholars and scribes, learning the art of shaping letters in ink on parchment. I came upon Wihtburh when she was but a simple nun in a small convent, her talents hidden beneath the modest veil of a sister’s habit. Yet it was quickly clear she possessed the gifts of intellect and language. As a woman of ambition much like myself, she would not stay at Ely or as a nun for long. Wihtburh soon followed me on my journey, keeping vigil by my side and steadily documenting the chaos and upheaval that descended upon us. I charged her with the duty to wield her pen with the precision of a sword, to record for posterity the events that swept me into the maelstrom of warfare and diplomacy as the Saxons and Danes stood poised, battle-ready, each awaiting the other’s first move. At my shoulder, Wihtburh chronicled the bloody struggles and shifting politics that tore through our lives like a relentless storm—the tempest that brought my father’s days to an untimely close.

Wihtburh will tell all, beginning with the day I was first summoned back to East Anglia.

Theodford, Kingdom of East Anglia, early 902 AD

Elinor moved through the mead hall with the grace of one born to command, though her voice rarely rose above a whisper. The firelight danced across the folds of her woollen gown, dyed the deep green of pine forests and trimmed with golden braid, each skilful stitch a mark of her courtly seamstresses. A finely wrought cloak hung from her shoulders, clasped at the breast with a silver brooch shaped like a serpent swallowing its tail—a symbol as old as the land itself.

Her hair, the colour of wheat at harvest, was wound intricately around her crown and veiled beneath a sheer length of linen. Only a few strands escaped to frame her face, softening the resolve in her grey eyes. Those eyes, so often quiet and observant, missed nothing: not the sideways glance of a nervous thane, nor the heavy step of a messenger with tidings from her father at the border.

Elinor wore her lineage like armour. Daughter of kings, niece to saints, she bore the burden of East Anglia’s fading power with the stoicism of her forebears. Around her neck, a strand of amber beads caught the lamplight—a gift from Norse traders meant to curry favour. At her belt, an embroidered pouch held a small wooden cross and a copy of the Psalms in Latin, her fingers tracing the words in prayer and study each morning.

Though few dared challenge her, those who did learned quickly that her silence was not submission, but calculation. Her strength lay not in swordplay or brute command, but in the sharp precision of her mind, the alliances she nurtured, the loyalty she inspired in warrior and monk alike.

To the common folk, she was a figure of awe—part woman, part legend—an icon whose long absence from East Anglia had only served to enhance the tales woven around her until she had reached mythical status. And to those who knew her best, like the demure Wihtburh, whose hand she had so recently held, Elinor was something rarer still: a hope for a kingdom caught between old gods and a new faith, between war and the dream of peace.

The rustle of fabric and the soft clink of metal accompanied Elinor’s deliberate steps towards her confidante. The air was silent save for the occasional whisper of pages turning as Wihtburh pored over the scrolls in her lap. The only audible sound was the subtle creak of wood as Elinor sat down beside her, the quietude emphasising the silence of their unspoken conversation.

The faint scent of candles and incense lingered in the air, but it was overcome by the sweet aroma of blooming flowers that adorned Wihtburh’s hair. Elinor felt soothed by the delicate fragrance as she gazed into her friend’s eyes.

Seeking answers about their blossoming friendship, Elinor held Wihtburh’s gaze. She was struck by the depth and clarity of her ice-blue eyes. They seemed to hold centuries of wisdom and warmth, a stark contrast to the piercing gaze Eadgifu used to give. Wihtburh could never replace Eadgifu in her heart, but that beating hub of her affections had room for both. Whereas she had looked up to the Kentish lady, her senior by a few years, the situation was now reversed, for although Wihtburh rarely wasted words, speaking discreetly when spoken to, her deference and esteem for her princess shone through. Elinor preferred people of few words, but those utterances had to be weighty and well-pondered, as in the case of Wihtburh.

Now was the moment to share her anxieties, for the weight of the world had settled on her young, slender shoulders, making her feel as if she were carrying a burden too heavy to bear. Her father was at fault, she knew that, but she could understand his motivations; yet, how could she express the storm of emotions swirling within her in words?

“Wihtburh,” she began, her voice trembling with her concerns, “my father commands independent support and sympathy in Wessex for his claim both to estates and kingship. His uncle manipulated endowment in favour of his son, Edward, but that kingship was never Alfred’s to give. It is clear to everyone that the greater amount of landed wealth he could bestow upon Edward, the stronger he made his son’s position in this contest for the kingship. Oh, my dear, how I suffer! My father’s heart is near to breaking, but I cannot help but think that he is mistaken.”

She paused, her eyes brimming with unshed tears, and continued, “You have written down how he persuaded the Danish jarls to fight against Edward on his behalf. But is it not wrong? Should we Saxons fight against our brothers with the foreigners’ axes dripping with the blood of our kinsmen?” Her voice cracked with emotion, and she clutched at her chest as if to contain the despair threatening to spill over. “And worse than that, my father is fighting the husband of my dearest friend on this earth. How I despair!”

Wihtburh listened intently, her features displaying a mix of concern and understanding as Elinor poured out her heart. She reached out a comforting hand to grasp the princess’s, offering her silent support in the midst of her turmoil.

“Elinor, my dear friend,” Wihtburh began softly, her voice gentle and reassuring, “your burdens are heavy indeed. It is no easy thing to see those we love torn apart by such conflicts, especially when it is our own kin at odds with each other.”

She paused, choosing her words carefully as she considered how best to offer solace to the troubled princess. “But know this, Elinor: in times of great strife and uncertainty, it is our loyalty to our own hearts and beliefs that must guide us. Your father may be driven by his own convictions, but you must follow the path that rings true to your own spirit.”

Wihtburh’s eyes bore into Elinor’s, their icy depths mirroring the unspoken strength and resilience within her. She spoke with a clarity that cut through the haze of confusion clouding Elinor’s mind. It was almost as if Wihtburh’s former abbess at Ely were speaking through her friend’s mouth.

“Remember, Elinor, it is not the circumstances we are born into that define us, but the choices we make in the face of adversity. Your heart knows the way, even when the path ahead seems shrouded in darkness. Let the Holy Spirit be your guide,” Wihtburh continued, her voice unwavering.

Elinor felt a flicker of hope ignite within her at Wihtburh’s words. “You are right, Wihtburh,” Elinor said, her voice steadier now. “I cannot alter the course of events set in motion by my father, but I can choose how I respond to them. I will stand by my beliefs and uphold what is true and just, even if it means standing against my own. It seems that the king has led his host into Mercia, where they are ravaging the countryside. When he returns, I’ll show him in no uncertain terms whose daughter I am, and that the frail body of a woman, unsuited to wielding a battleaxe, can yet contain the heart of a housecarl.”

Although Elinor had a vested interest in Wihtburh’s chronicle, she feigned indifference to its progress not to put her friend under pressure. “Let me see what you have written, dear friend.” She sat close to her, shoulder touching shoulder, and read easily:

Chronicle Day 1 Wednesday May 10th, 902 Anno Domini:

Today, as the wind sweeps dandelion clocks along the stone pathways of Cooling, a rider on a sturdy mare approaches, the clatter of hooves echoing in the silent courtyard. Clutched in his weathered hand is a sealed parchment bearing the sigil of King Æthelwold, by God’s grace, King of the East Angles, intended for my lady, Elinor. Her eyes widen in shock and uncertainty as the years of being raised in the nurturing yet unfamiliar care of Lord Sigebert, Ealdorman of Kent, are suddenly upended by news from her actual bloodline. I watch her face drain of colour, each second marked by trembling breaths until the rider, with deliberate care, presents her father’s melted wax seal as if unlocking a long-forgotten secret.

“My Lady, your father commands you to travel forthwith to his court in Theodford. He bids you arrange with Lord Sigebert to secure an escort fit to guarantee your safety, Princess. That is all.” With those formal, clipped words, the messenger lowers his gaze, bows his head, and slowly steps back into the dim light of the unlit hall.

“Wait!” Elinor sharply interrupts, her voice quivering with both anger and disbelief. My lady’s voice, laced with both trepidation and indignation, resonates off the wooden beams: “Commands, are you absolutely sure he used that word?”

“Ay, my Lady, I am certain he did,” the messenger replies, his tone measured and unwavering.

“Then, you must inform my king that I shall speak with the ealdorman about his request and give it my earnest consideration.” Her eyes flash with defiance as she brushes off the messenger with a graceful, regal wave of her hand.

Once she dismissed the messenger, I approached her side. I found her pacing in her private antechamber, where the cooling shadows of twilight mingle with the flickering candlelight. Her hands, trembling as they grip a plush duck-down pillow, reveal the suppression of an inner storm; each punch that lands on the soft cushion is a silent outburst of the rage and hurt that has been bottled up over the years. Bitter tears trace down her cheeks, each drop catching the guttering glow of the candle as I come to her side and murmur comforting words.

“But Wihtburh, what does he want of me after all these years?” she laments in broken whispers between sobs. “For all I know, he has remarried—although we will find that he had not—eleven years without even a single word. First, I lose Eadgifu, and now I must bid farewell to my kindly foster-father—oh, my dear friend, how unbearable this fate is!”

Later, with heavy hearts, we cross the great hall together and go into Lord Sigebert’s private abode. A mix of sorrow and reluctant duty hardens her lovely visage as we reach his door. Welcoming us warmly, the kindly ealdorman stands tall and stately, his kind eyes crinkling at the corners when he smiles. His hair is starting to grey at the temples, but it only adds to his distinguished appearance. He wears a simple yet elegant tunic, adorned with intricate embroidery, the colours of his house emblem proudly displayed.

He embraces Elinor, his arms as reassuring as the spring sunlight of the dying day that filters through the high windows, carrying the scent of fresh herbs and earth, a hint of sage and rosemary lingering in his wake as he releases her. It is a comforting smell, one that brings to mind hearth fires and cosy meals shared with loved ones. He whispers tenderly that she is as dear to him as his own beloved Eadgifu, but his brow furrows with the encumbrance of tradition as he reminds her that in the realm of kings, commands are neither negotiable nor softened. “A king commands, my dear, he neither asks nor implores. You must not take exception to his regal manners.”

In an effort to lessen the sting of the inevitable parting, Lord Sigebert presents her with a finely wrought gold armlet. Its surface is etched with elegant patterns, catching the light and reflecting a promise of cherished memories from her time at his court.

“Oh, father!” she exclaims, her voice trembling with gratitude mingled with sorrow. “It is indeed a splendid gift, but I need no other keepsake than the thought of you and my dear sister filling my heart with joy. I shall wear it as a harbinger of good fortune and a constant emblem of my undying love for you.”

Then, with the tenderness of a secret shared only within the confines of their close bond, she rises on tiptoe, her eyes shining with unshed tears, and presses a soft kiss onto his brow—a kiss that requires him to bend slightly, its gesture capturing both reverence and the bittersweet nature of their impending farewell.

Elinor looked up and her eyes were bright, again with the threat of tears, “Oh, my sweet friend, you have captured all my sentiments: the fears and anxieties of my youthful passage to maturity! I have done well to entrust my chronicle to you, I could never have laid my soul bare in this way. I can read no more for now!” She squeezed her friend’s hand and brought it to her lips.

Theodford, May 902 AD

The journey to Theodford from Cooling had been long and wearisome for the two women, testing their good nature and girlish excitement with a variety of discomforts along the way. They endured several crossings on rough-hewn benches in ferries that lurched over turbulent estuaries. The relentless pitching of the boats brought to mind the ancient tales of Odyssean wanderings that Elinor had read in her foster-father’s library, where each crossing seemed an epic in itself. Yet worse still was the jostling carriage ride on the other side, which the women had hoped would be their relief. Though intended for noblewomen, with soft down cushions and padded walls made specifically to accommodate the journeys of the fair sex, the carriage proved a torment. Each jolt and shudder sent them anew against each other and the plush confines. Even such banal luxuries could not fully compensate for the morass of rutted roads they travelled. Weeks before they had set out, these tracks would have been impassable, but the early-spring sun had at least rendered the muddy surface viable, if only barely. Wihtburh worried constantly that an axle would break and they would overturn, but she kept these thoughts to herself. They drew near to their destination, the anticipation of arrival only amplifying each uncomfortable minute of the journey. In spite of it all, Elinor and Wihtburh felt relieved to finally arrive at Theodford.

They had spent the first night in the comfort of the royal palace after Elinor’s reunion with her long-separated father, enjoyed a festive meal in the princess’s honour, and sunk gratefully onto a comfortable bed, where refreshing sleep embraced them. Wihtburh retired later than Elinor, fighting weariness and aching bones to do her duty and set down the account of her mistress’s reunion with her father.

Elinor woke with a severe headache brought on by the stress of the journey and the encounter with the king, so she ordered Wihtburh to search out some herbs that would bring relief for the pounding behind her eyes. As the morning sun rose and piping swifts winged past the eaves, she began to feel better—well enough to take a sneaky read of Wihtburh’s latest scribblings. That was her choice of word, for, in truth, she had to admit that her friend’s calligraphy was exquisitely precise, with every loop and scroll executed immaculately:

Chronicle Day 2 Thursday May 11th, 902 Anno Domini:

While the household scurries with preparations, only I, a humble scribe, am privileged to glimpse the tumult within Lady Elinor’s mind and heart as she prepares to meet with her father, King Æthelwold. Such intimations she has granted me, secrets revealed as if the sheer act of confession could unburden her soul. She admitted that some part of her could never forgive him for the detachment she had borne, isolated far from his affections in Kent, like a sparrow abandoned from its nest. It was Sigebert, her foster father, who had been the sun around which her life circled, the centre of her universe. Her love for him is greater than what she feels for her birth father, although she trembles to speak this truth aloud, as it wounds her even to say so. Most pressing are the questions, an unending stream to which there seems no embankment. They pour from her like cascades of a river flowing over granite, each inquiry more urgent than the last, each one swollen by winter snowfalls and springtide storms. Would he still love her, the father who sent her away? Would she find it in her heart to like him, this man who is both familiar and strange? What did he want of her after all these years? Was there some grand design or looming expectation of which she was unaware? And so forth flooded her mind; so forth, drowned her thoughts.

No such misgivings torment me, the humble Wihtburh. My eagerness is very nearly serene by comparison. The meeting arrangements occupied me entirely, obedient to my mistress’s every whim, and I direct the servants with the precision of a general. Of course, I am untroubled by doubts or uncertainties, basking in the novelty of Theodford and what I hope will be their warm welcome by Lord Byrhtnoth and his kin. The disparity between the two of us could not be more pronounced; I hope that my cheerful anticipation serves as a foil to Elinor’s private agitation. As these contrasts unfold, the servants haul in crates and trunks while delegates from the kingdom scuttle about, assuring each detail is properly attended. The ladies’ quarters brim with activity and the clamour of preparations. Not least among the priorities, warm baths to rinse away the dust of the country roads settled upon us.

Imagine the state of affairs, then, as these matters unfold.

Her servants dressed Elinor in her finest gown and entwined jewels in her hair, clipped a fine silver brooch at her shoulder, and she insisted on slipping on the gold armlet that Sigebert had gifted her. I can testify that never a more lovely vision was beheld in the whole of East Anglia as her gown rustled against her thighs as we made our way into the royal presence. I could fill my parchment with a description of the wondrous drapes, carvings, and battle trophies adorning the walls, but that is not my purpose. Far more important is an account of the touching moment when the king and his daughter embraced after so many years apart. I swear that the rugged, lined face of Æthelwold, who had lived through many hardships and battles, waged its own struggle to forfend the victory of his emotions on seeing his long-lost child so beautiful and graceful now rushing into his arms. I suspect he maintained his dignity by burying his tears in her flowing locks. Their embrace seemed to last an age. At last, the king released her and his loving smile calmed my lady’s fears, but almost at once his sanguine nature emerged as he spied her armlet. “Bah! How is this possible? Someone has beaten me to the gift I have jealously set apart for my daughter!” He produced an equally beautiful golden armlet and looked as if he wished to hurl it in a midden pit.

“Oh, father, it is exquisite,” my lady almost snatched it from his hand. “I could not have wished for anything more lovely or precious.”

“But you already wear one such, daughter.”

“What of it, my king? I shall wear yours on my left arm, nearest to my heart. This other was a parting gift from kindly Ealdorman Sigebert, who has treated me like a daughter these years. With a token of his love and yours,” she slid the gold ring up her left arm, and coyly held out both arms for his admiration, “I shall ever be the happiest woman in the land.”

“It is well that it is so, my beloved daughter,” King Æthelwold said elegantly enough.

Lady Elinor looked the picture of joy, but soon enough she would have other worries to trouble her youthful mind.