3,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

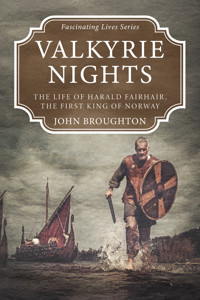

In the age of warring jarls and walking gods, Harald Fairhair was destined for greatness.

When the Norn-Valkyrie, Skuld, changed his fate, and the maiden Gyda rejected him, Harald swore not to cut his hair until every fjord bowed to him. Through years of conquest, his wild locks matched his growing power.

Victory brought him Gyda and the crown, but peace brought new enemies. In his final days, Harald struggled to secure his legacy through his heir, Eirik Bloodaxe, before the gods claimed their due.

VALKYRIE NIGHTS is a saga that chronicles the life of a man who forged Norway... and paid a heavy price.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Valkyrie Nights

THE LIFE OF HARALD FAIRHAIR, THE FIRST KING OF NORWAY

FASCINATING LIVES SERIES

JOHN BROUGHTON

Contents

Preface

1. Vestfold, Norway, 860 AD

2. Vestfold, Norway, 863-872 AD

3. Hafrsfjord, south-west Norway 872 AD

4. Hafrsfjord, Rogaland, 872 AD

5. Hålogaland and return to Vestfold, 874-876 AD

6. Avaldsnes, Vestfold, 876 AD

7. The North Sea and Iceland, 880 AD

8. The rebellious north of Norway, 884 AD

9. Jutland, winter 890–892 AD

10. Northern Norway, 894 AD

11. Hjaltland, Orkneys, Man and Scotland 898–899 AD

12. The Viken shore and the wilds of Finland, 900-910 AD

13. Møre, Norway, 910 AD

14. The Baltic Sea, and Finmark, 914 - 922 AD

15. Norway and lands around the North Sea, 922 - 928 AD

16. Royal residence, great hall, Stavanger 924 AD

17. Winchester, Wessex and Lade, Østbyen, 925 AD

18. Tunsberg and Saeheim, 928 AD

19. Hogaland, 933 AD

20. Earlier in Hogaland, 933 AD

Appendix

About the Author

Historical Novels Also By John Broughton

Mystery-Thriller Novels Also By John Broughton

Copyright © 2025 John Broughton

Layout design and Copyright © 2025 by Next Chapter

Published 2025 by Next Chapter

Cover art by Lordan June Pinote

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author’s permission.

Preface

THE WELL OF URD, ASGARD, 860 AD

Skuld, whose name meant that which is intended, stood at the brink of the Well of Urd, her delicate hands trembling as she held the silver thread of fate. The other Norns—her sisters, patient and ancient, so old their skin seemed carved from petrified wood—chanted softly as they dipped their spoons into the holy waters and sprinkled the roots of Yggdrasil. Skuld envied their calm, envied their certainty in their appointed tasks, envied the hush of contentment that settled over their faces at dusk when the day’s weaving was done and all souls—man and god alike—were, at least for a moment, undisturbed in their own destinies.

Skuld could not share their stillness. Her dreams were filled with visions not just of the world-to-come but also of the world-that-should-be. The future throbbed in her like a wound. The new religion, the one with no wolves or serpents or blood, was spreading across Midgard like ice bands on the sea, pushing back the warmth of the old faith, driving the brave and laughing warriors of Valhalla into the shadows of their own mead halls. Skuld awoke each day with a scream caught in her throat, the echo of a thousand lifetimes flickering past her eyes, each one greyer and more silent than the last. In the vision of tomorrow, even the gods grew pallid and thin, their voices lost to the winds that once carried their names in saga and song.

It was this horror—a future emptied of passion, a future where the gods blinked out like spent stars—that brought her, in secret and trembling, before the All-Father one frostbitten morning. She found him sitting on his throne, his ravens bickering at his feet, his wolves curled at his side. Even seated, Odin dwarfed the hall. His beard, gone to iron, bristled with runes; his cape was a storm cloud thrown across his shoulders. He sat wrapped in a contemplative silence, his single eye fixed not on Skuld but on the horizon, as if the world’s fraying edge were a trick of the light he could mend with a single squint. Odin sipped from his flagon and gestured for her to approach.

“What ails you, daughter?” the one-eyed king asked, voice hoarse with thousands of winters. His eye, when it finally turned to her, was grey and all-seeing, a disc of cold prophecy.

Skuld bowed low and felt the weight of past and future in the marrow of every bone. “Father, I do your will and weave the future of mankind, but, alas, I am sorrowful because the future is governed by the past and the present.”

Odin nodded, a subtle smile playing at the corners of his mouth, like a man who already knows the end of the riddle. He closed his eye, and for an instant Skuld thought she had bored him into sleep—but then he spat a laugh so sudden that the ravens startled and the hall echoed with their caws. When he opened his eye again, it burned with a new, sharp light.

“It has always been thus, child. Why are you unhappy to weave, ride, take the slain and decide fights?”

Skuld’s hands twisted in her lap. She wanted to scream, to shake the throne, to demand a world where fate was not a thread but a torrent that could wash away the past. Instead, she bit her tongue till it bled and forced the words out slow and even, like a penitent reciting her sins.

“I am not ungrateful, Lord. Do not misunderstand me, I’m sorrowful. This new, pallid religion is replacing the true gods in folk’s hearts.” She stared at the floor so the All-Father could not see the tears brimming in her eyes. “I beg to be allowed to intervene.”

Odin drummed his fingers on the arm of his throne, the sound like distant thunder. He said nothing for a long moment. The air was full of the smell of wet fur and old wine. Skuld stood motionless, feeling her heart pound against the cage of her ribs.

Finally, he spoke, careful, as if pronouncing a curse. “Very well, but you have my permission to intervene with only one mortal. Choose well: that is my command.”

Skuld’s breath caught, and for the first time in many years she felt the pulse of hope—faint, but there. “Bless you, All-Father. I shall not waste the opportunity.”

Odin grinned, and for a heartbeat he was not a god but the oldest man in the world, cunning and tired and desperately in love with his own children. “Nor shall I. Tonight you’ll sleep with me. There’s time; the battle is not till tomorrow.”

Her sisters, who had stood silent in the shadows, gasped in unison and drew their hoods over their faces. For Skuld, the command was not a surprise. The old gods were always greedy for unions that could birth something new, or at least stave off the end a little longer. She nodded and allowed herself to be led away to his chambers.

When the doors shut behind her, Skuld found herself seized by a dizziness that was not altogether unpleasant. The room was warm, lit by the flicker of a hearth-fire and the glint of polished shields on the walls. Odin doffed his crown and let it fall onto the furs with a clatter, then turned to her with a look she could not read. His hands were heavy but gentle. He did not speak, but the air shimmered with unspoken words—a language older than sound, a communion of memory and want. When he took her, it was as if she were woven into the very fabric of the world, each motion a new line in the poem of creation.

Afterwards, he cradled her against his chest and stroked her hair, and Skuld felt the strange peace of something both fulfilled and just beginning. “You are not like the others,” Odin murmured. “Go now, and be what the world needs.”

She left his chamber at dawn, her limbs aching, her mind ablaze. In her heart, she carried a new power, something Odin had planted in the deepest root of her being. She would use it to change the fate of one mortal, but, Skuld thought as she entered the morning mist, one might be enough.

Her sisters awaited her by the Well of Urd, their faces unreadable. Together, with no words, they resumed their weaving, but Skuld’s thread shone brighter than it ever had before.

She began to search the skeins of fate for the mortal who would be the instrument of her last hope, and as she worked, she felt Odin’s gaze upon her, patient and unyielding, waiting to see what she would make of her sorrow.

Vestfold, Norway, 860 AD

Harald Halfdanson, son of King Halfdan the Black, fought like ten men and that was his downfall. His bloodied battle-axe had slain seven Swedes, including a nobleman. Was it exultation that made him careless as never before? Or his wyrd? Whatever, he dropped his guard and a Swedish spearman thrust his sharp-pointed spearhead into his chest so hard that it appeared out of his back. He screamed as atrocious pain seared through him, and blood stifled his voice as he fell backwards, dying. Harald’s face contorted in agony as he let out a blood-curdling scream. His body jerked back, blood spraying from the wound in his chest. His brother’s eyes widened in horror as he saw Harald fall to the ground, his face pale and lifeless. Magnus saw him fall and, berserk, slew the enemy spearman with the might of vengeance.

That was when she arrived, unseen as the battle raged on. Skuld pulled out the heavy ash pole from his body and tossed it aside with such strength that it might have been a mere toothpick. She bent over him and did the opposite of her usual practice. She persuaded his soul not to leave his body, whispering, “Your time has not yet come.” The battle was a chaotic blur of swinging weapons, roaring warriors, and splatters of blood hovering in the air. But amongst it all, Skuld stood over Harald’s limp body, her hand glowing with a soft light as she healed his fatal wound. Her lips met his in a life-giving kiss, her breath entering his lungs, and his body stirred and groaned in response.

He no longer felt the atrocious pain, so he tried to rise, but she pushed him gently down. “Lie still; the enemy is coming.” And they were. The Swedes charged towards them, their armoured bodies glinting in the dim autumn light. They raised their weapons, ready to strike at the enemy. Skuld stood tall, a foot planted either side of Harald, her arms raised above her head, her form shimmering in the light as she radiated power and grace. Three of the warriors fell to their knees, recognising her as a goddess, while the other two glared towards their king, Erik Weatherhat, who had enforced their baptism, with looks of disdain and anger. Skuld looked up into the sky. Only she could see her sister Valkyries: Hrist, Mist, Herja, Hlökk and Geiravör on their steeds, gathering the souls of valiant fallen warriors to carry them to Valhalla. She waved and returned to the business at hand, “Retreat,” she addressed the five Swedes, arms still aloft. “This one is mine and no harm shall come to him.” They were too wise to disobey a goddess, so they about-turned and re-engaged in the battle elsewhere.

“Up you get, Harald Halfdanson. Take that sword,” she said, pointing at the slain nobleman, whose hand still held the weapon. With difficulty, he pried the stiff fingers off the hilt and took up the blade as commanded.

“Now, follow me!” she ordered briskly. “We must away to the sacred grove.”

She slipped away, barely more than a shadow, as if she could evaporate into the night at a thought. Harald attempted to follow with the same ease but found each step strange, disconnected, as if his limbs belonged to someone else. Nevertheless, he was not in pain—if anything, he felt a cool, lucid vigour spreading through his body, the kind of energy that could carry a man all the way to the moon if only he could direct it. But his thoughts kept tangling, ideas drifting loose and disintegrating before he could grasp them. The only beacon in this fog was her white dress, phosphorescent against the darkness, always one stride ahead of him, and the compulsion to pursue.

They descended the hillside. The moon feathered the ground with light, but the path soon curled deeper into the woods, and silver became shadow. Each step was a challenge; Harald’s boots sank in the moss, rooting him briefly, and the air pressed down from above as if the branches themselves were watching. The farther they went, the denser the trees grew, until the path became little more than a memory of one, furrowed by generations of feet but now nearly erased by darkness. Pine needles braided together underfoot, woven with twigs and the detritus of forgotten seasons. At some point, the hush of the forest grew so profound it was like a sound in itself. Harald could hear only the wet rhythm of his own lungs and the measured breaths of the woman ahead, sharp and even as a metronome.

She led him with unerring certainty, never turning to look, never hesitating at a fork or a tangle of brambles, as if drawn by magnetism or something even older. There were moments when Harald felt sure she would simply dissolve into the gloom and leave him stranded, but always she reappeared, willowy and untouchable, glancing over her shoulder just long enough to signal that he was meant to continue. He felt both the hunted and the hunter—panic and desire braided in equal measure.

The undergrowth changed subtly as they progressed. Trees gave way to ancient boulders dappled with lichen, and the air became charged with the earthy aroma of damp stone and old leaves. The forest no longer felt merely alive: it was animate, conscious, and intent upon their passage. Harald’s mind, emptied of rational thought, began to fill with images that had nothing to do with the world he knew: the lilt of a mother’s lullaby, the metallic tang of blood on his tongue, a flickering vision of his father’s hand—large and trembling—hovering over his brow. Each memory was as vivid as the present moment, and each vanished as quickly as it had come, leaving him hollowed out and newly receptive.

Twice they passed animal skeletons—bleached and fragile as soap, ribs thrust upward in mute appeal. Harald stepped carefully around them, half-expecting the bones to reassemble and give chase. The forest pressed closer, the canopy knitting itself into an almost perfect dome overhead, so that the only illumination came from a thin, eerie blue radiance that seemed to pulse from the bark of certain trees.

When the trail finally widened, it did so with a suddenness that felt purposeful, like a set piece revealed at the climax of a saga. They entered a glade so symmetrical it seemed architected: a circle of grass, soft and luminous, bound by a palisade of pines and birches. In its centre stood an ancient oak, massive and solitary, its trunk corded with age and its branches bent in a posture of perpetual benediction. The air around the tree shimmered—Harald could see it, the way you see the heat above a summer cornfield. It vibrated with meaning.

His eye was drawn at once to the branches. They were weighted down with hundreds of objects, each one dangling on a string: ragged strips of gaudy cloth, knotted ribbons, lengths of twine suspending trinkets and toys, tiny glass beads, and the odd coin wedged into the bark. Some gestures were childish, others desperate. There was even a pair of shoes, caked in red mud, swinging from their laces. Each offering caught a fragment of moonlight and tossed it sideways, so that the oak glittered like some monstrous chandelier.

At the base of the tree, the ground was worn bare, but not by animals. Footprints—some small, some adult, some barefoot and others shod—crisscrossed the soil, preserving a map of ritual. Tucked into the cracks of the roots were more gifts: candles melted down to nubs, wilted posies, a seax buried to the hilt, a handful of teeth in a linen pouch. The tree was both altar and archive, alive with the residue of every person who had stood here before.

Harald’s heart began to hammer. He understood, distantly, that he was witnessing a place of great consequence, a site of collective longing and fear. The feeling was not religious, at least not in any churchly way—more like the awe you feel looking into the mouth of a cave, or the first time you realize that the ocean is bottomless.

The woman stopped abruptly, as if some boundary had been reached, and Harald nearly collided with her. They stood together in the clearing, he a trespasser in a world that was at once utterly foreign and intimately familiar. The air was charged, humming with anticipation. It seemed to him that the very leaves were waiting, and that if he listened closely, he would hear the names of the dead whispered in the sibilant movement of the branches.

That was when the wind changed, carrying with it a scent like burnt honey.

“Strip to the waist,” she commanded, and smiled grimly at his unblemished chest. She took his upper garments and draped them over a branch, for not even a Valkyrie could short-change the gods. In a fair exchange, she reached up for a leather battle-sark. “Here, put this on and hand me the sword.”

Like an enthralled creature, which he momentarily was, Harald obeyed. The sark was a perfect fit, as if measured for him. He watched, agape, as she took the blade and with her fingernail incised runes along it. No mortal feat this. She wrote his name: Harald Halfdanson, followed by forever victorious. “Kneel,” she ordered. Standing in front of him, she drove the sword into the sacred soil and placed a hand on his head and the other on the hilt. “May you, Harald Halfdanson, be a great warrior, with the wit and skill of a god. This, by command of the All-father.” He felt energy and strength the like of which he had never felt before surge into him. She smiled happily and, for the first time, he noticed her radiant beauty. “Stand!” She tugged at the sword and held the blade in both hands. “Every sword must have a name, Harald. What name will you bestow upon it?” He closed his eyes, stepped forward to place his hand upon the rough bark of the sacred oak, and breathed a simple prayer to Odin, who replied with a name: ‘Skuld,’ he said, and bowed.

“An excellent choice,” she beamed. “So be it!” She turned the blade over and her nail flew across the other side of the blade, incising her name in runes. “There, it is done! Now, remember, only unsheathe this blade to keep it well-honed and oiled or to draw blood,” she said, smiling grimly. “Your sark has a scabbard built into its back.” She sheathed the sword. “Carry it on your back always until needed in battle, my warrior,” she told him. He groped for the hilt over his shoulder.

“You will get used to it. Never again fight with a battle-axe—only with Skuld, understood?” He nodded dumbly, but now his thoughts came teeming.

“What shall I do now, Skuld?”

“Go to your father’s hall.”

“Impossible,” he breathed rebelliously.

“Why?”

“Because my brother and his men saw me fall. They believe me dead.”

“Precisely. And that is why you must go to them and show them you are blessed. One day you’ll be their king. But I have yet to weave your wyrd.”

“How can I ever thank you?”

“By keeping the faith with your people. Make the just sacrifices. We’ll meet again soon, Harald…for the moment… Halfdanson.”

That was mysterious. He looked at her, perplexed.

“Never mind,” she beamed. “I will leave you now, for I must grant your grieving father sleep and whisper in his dreams so that he is ready to receive you. Be sure to arrive before the first cockerel crows.”

He blinked, and when he stared around, the glade was empty and still. Only the ancient oak’s leaves rustled, and some fell at his feet. He stooped, picked up a yellowing leaf, kissed it and tucked it into a pocket of the sark. Only then did he set off, his mind racing. Skuld the Valkyrie! I have met a goddess. She brought me back to life and will shape my wyrd! I must do as she says. He hurried away down the trail to the fringes of the forest, which he knew well from hunting. Even as night descended, he travelled sure-footed and full of energy towards his father’s hall.

Harald stood before the gate of the palisade surrounding the king’s hall and, as the first cockerel crowed, called up to the guards, “Open the gate, it is dawn and I am the king’s son, Harald!” The words echoed through the chill morning, unsteady and uncertain at first, as if he spoke into a void that remembered him only as a ghost. The timbered doors of the fortification creaked open a hair’s width, reluctant, shuddering on their old iron hinges. Then, wider, slowly. Two guards peered through the gap, their faces white at the edges with frost and with something else: fear and disbelief.

“Harald?” one muttered, blinking. He leaned forward, squinting into the gloom where a figure stood outlined against the waning darkness. “By the gods, it is him. Alive!” The rumour passed like a ripple through the slumbering settlement—Harald Halfdanson, thought dead, had returned at the dawn.

He passed through the threshold, the early mist curling around his shins. His thoughts, still swirling and confused, found little purchase in the world of the living. His feet knew the way; his heart did not. He made his way to the great hall, its roof thick with the smoke of last night’s embers, and paused only to shake the dew from his hair and to steady his hands, which trembled not from cold but from something deeper, something unsettled.

Inside, the torches burned low on their iron sconces, casting murky light onto the benches and tables. Few were awake at this hour. The servants muttered among themselves, setting out trencher bread and salted fish, preparing for the day as always, but when they saw him, their hands stilled. A cup dropped to the reed-covered floor and shattered. Someone made the sign against the evil eye and a young girl fled into the shadows. But he kept walking.

He had a special place in his father’s heart because he was born of his second wife, Ragnhild, whom he had kidnapped from Hake so that he could marry her. Ragnhild, though silent and unbending, held a proud light in her eyes, and Harald alone among her children inherited it, though his hair was spun gold to his father’s night-black. Halfdan was called the Black for his own hair, his temper, and his moods; but it was he, pale and fair, who seemed the contradiction—Halfdan’s favourite, though he would never say as much aloud.

When Halfdan first heard of his son’s death at the spear of a Swedish foeman, he had believed his own heart would shatter in his chest. He withdrew from his duties, shuttered himself behind his carved doors, and commanded his servants not to disturb him. All through the night he lay upon the high seat, staring into the smoke-curled rafters, waiting for the darkness behind his eyes to consume him and deliver him from the pain of loss. Yet, strange to relate, near midnight his limbs became heavy and his breathing thick, and against the logic of grief he fell into a stupor, a sleep so deep it was unlike any he had ever known. In that sleep he dreamt vividly, as real as waking: Harald, hale and smiling, standing at the gates to the hall at sunrise, calling up to the guards and demanding entry. The vision was so clear, so insistent, that at the first crowing of the cockerel he snapped upright, still dressed in his mourning garments, and made ready to greet his son as though the thin veil between life and death could simply be brushed aside by kingly will.

Magnus, the younger brother, was not so easily convinced by dreams, nor so easily consoled. He had not slept at all, pacing the long narrow aisles of the hall, haunted by the memory of Harald’s death—that moment when the spear pierced his brother’s chest and Harald’s mouth gaped with a red, silent scream. Magnus had not believed it at first, even as he saw the light fading from Harald’s eyes. He had always envied his brother’s favour, but to see Harald die was to lose a part of himself, a shadow that had always defined the direction of his spirit. He walked in circles, rehearsing what he would say to his father, to the household, and failing to find any words that were not ashes in his mouth.

So, when Harald stepped into the great hall, the reactions came in waves. First a hush, as every voice and spoon and goblet paused in mid-air. Then a susurration, like the wind through a cornfield, as the rumour flew from mouth to mouth. He’s back. He’s come home! He’s alive. Magnus, caught in the middle of the room with a flagon of mead in his hand, turned and stared at the doorway as if he’d conjured his brother by will alone.

Harald’s father brushed past Magnus without a word, seized Harald by the shoulders, and for a moment only stared into his face, searching for the wound, the scar, the sign of death. When he found none, he drew Harald into a crushing embrace, smothered his son’s face with rough kisses, and then, in the same motion, spun around to glare at Magnus with black fire in his eyes.

“Harald! You are alive! Exactly as I saw in my dream!” The king’s voice rang out, half accusation, half relief. He shook Harald again, as though to make certain the flesh would not dissolve into mist.

Magnus stood frozen, his mouth working, his hands knotted at his sides. “Father, I swear, I saw Harald skewered by a Swedish spear. He died before my eyes. I cut down the man who killed him myself—by Odin, I did!”

“And yet, here he is—hale and hearty!” The words spat out, sharp as a blade. Halfdan raised his hand to strike Magnus, but instead let it fall to his side, unwilling to mar the new perfection of his restored family.

The household had gathered, the retinue of warriors, the greybeard elders, the shieldmaidens and even the servants, all clustered near the dais. At the front, Lars Anderson, a veteran with a beard like lichen and a voice like gravel, stepped forward, his eyes narrowed in careful study. “Lord, I too saw Harald pierced by the spear and fall dead to the ground. This is a mystery!” He spoke as a man who had seen many deaths and never before a resurrection.

Halfdan turned to Harald, his face suddenly slack, all the fury and command gone. He looked older, smaller, as if the strain of the night had aged him. “What do you have to say, Harald?” the king asked, the question more a plea than a demand.

“It was indeed as Magnus and Lars say, Father,” Harald said. His voice no longer uncertain, but clear and resolute, as if something within had been reforged in the night’s passage. “Others will have seen it, too. But death was not my wyrd. The All-father, may his name be forever blessed, decided that I should be spared, for I must fulfil my destiny.” He paused, then in a swift gesture, tore open his battle-sark. “Magnus, run your hand over my chest. See if you can find a wound or even a scar.”

Magnus hesitated, as though afraid of what he might touch. But at a nod from his father, he stepped forward and placed his palm against Harald’s bare chest. The flesh was smooth, unmarred, the skin warm and alive. Magnus looked up, his eyes full of wonder and terror. “Father, it is unbelievable,” he whispered, “there’s no trace of any wound. Yet I know what my eyes saw.”

“And they did not deceive you, brother. We must trust in Odin. I do not yet know my Fate, but sooner or later, I’ll be told.” Harald’s words hung in the air, solemn and fateful.

The warriors in the hall pressed forward, jostling for a better look, their faces shifting from suspicion to awe as they beheld the living proof of the tale. Some knelt and made the sign of the hammer; others called out praise to the gods. A few, more superstitious, muttered about spirits and shape-changers, but none dared voice open doubt in the presence of their lord.

“My King, we are truly blessed!” Lars called, raising his sword in salute. “We must drink to the health and safety of my brother in arms, your son Harald.” The old warrior’s voice quavered, but the emotion beneath it rang true.

“Aye, Magnus, let it be so! Fetch the drinking horns. We shall talk of this happening and skalds will sing about it for years.” Halfdan’s command broke the tension, and the retinue sprang into motion. Horns and goblets were filled, benches dragged forward, a fire stoked to full heat. The servants who had earlier shrunk from Harald now flocked to set out the best food and drink, eager to serve the resurrected son.

As they drank, the tale spilled out: Harald’s fall in battle, the agony of the wound, the darkness that followed. Magnus described the moment when he had avenged his brother, and Harald told, in cryptic words, of his passage through the realm of shadows and being sent back by the will of the gods. The men listened, rapt, some weeping openly, others pounding the tables in approval.

“Tell us, son, what did you see when you crossed the threshold of death?”

He felt the pressure of their gazes, the anticipation that hung heavy like the smoke from the newly stoked fire. He took a deep breath, the scent of mead and roasting meat filling his nostrils, grounding him in the reality of the hall. The tangible, familiar surroundings helped dispel the lingering chill of the memory of death’s shadow. He looked around, seeing the faces of his kin, his friends, all eagerly awaiting his words.

“When I fell,” he began, his voice steady despite the turmoil within, “there was pain, yes, but then a coldness, a darkness that swallowed me whole. I remember the taste of blood in my mouth, the coppery tang that seemed to fill my entire being. Then, nothing.” He paused, his fingers tightening around the drinking horn. “I floated in that void, empty and endless. But then, came a voice. It was her, Skuld the Valkyrie, so sweet, so gentle. She told me it was not yet my time and she healed my wound and breathed life into me. I live to fight again! There’s more to tell, but it’ll keep for another time. Let me rest and drink my ale.”