Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Gibson Square

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

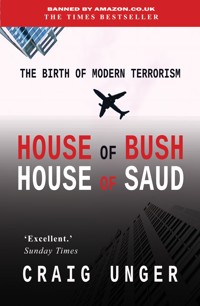

In 2001, the 9/11 attacks awoke the world to the military-style threat of Islamism. Due to the White House, the nationality of fifteen Saudis among the nineteen suicide bombers remained cast in shadows. In this exceptional tour-de-force, Craig Unger meticulously pieces together the US role in the birth of modern terrorism by relying on research and interviews with those who would prefer to deny the truth.The acclaimed account of the link between modern terrorism and Saudi and corporate greed whose first UK publisher cancelled for fear of libel, and which several online retailers dared not stock.'Excellent.'—Sunday Times'A notably intelligent piece of investigative reporting which lights the blue touch-paper.'—Observer'A forensic examination.'—Daily Telegraph'Very powerful.'—Guardian, book of the week'Hard-hitting.'—Independent on Sunday'An explosive book.'—Scotland on Sunday'None can match this.'—Irish Times'Well-sourced... cool, calm and collected.'—Times Higher Education Supplement'As chilling as it is gripping.'—Belfast Telegraph'Craig Unger has done America and the world a huge favor.'—Michael Moore, Director of Fahrenheit 9/11, the movie inspired by House of Bush House of Saud'Unger's meticulously researched book raises troubling questions about the ties between the Bush family and the Saudi royal family, especially in the aftermath of 9/11. It's a provocative read that challenges conventional narratives.'—The Washington Post'Craig Unger's House of Bush, House of Saud is a compelling and disturbing account of the intertwining interests of two powerful families. While some may dismiss it as conspiracy theory, the depth of research demands attention.'—The Washington Post'Unger's book is a gripping and unsettling exploration of the Bush-Saudi nexus. It's a damning indictment of how personal and financial interests can overshadow national security.'—The Guardian'Craig Unger's House of Bush, House of Saud is a meticulously documented account of the symbiotic relationship between two of the world's most powerful families. It's a chilling read that raises more questions than it answers.'—The Independent'Unger's book is a riveting and deeply researched exposé that sheds light on the shadowy connections between the Bush family and the Saudi elite. It's a sobering reminder of the complexities of global power dynamics.'—The Sydney Morning Herald'Craig Unger's House of Bush, House of Saud is a provocative and eye-opening investigation into the ties that bind American politics and Saudi wealth. It's a must-read for anyone interested in the hidden forces behind global events.'—Le Monde'Unger's book is a meticulously researched and deeply unsettling account of the Bush-Saudi relationship. It's a powerful critique of the intersection of politics, oil, and terrorism.'—Der Spiegel'Craig Unger's House of Bush, House of Saud is a provocative and deeply researched account of the intricate ties between the Bush family and the Saudi royal family. While some of its claims are controversial, the book provides valuable insights into the intersection of oil, politics, and terrorism.'—Foreign Affairs'Unger's book is a bold and controversial examination of the ties between the Bush family and the Saudi royal family. While some may question its conclusions, the depth of research and the questions it raises make it a valuable contribution to the field.'—International Affairs

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 651

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

About the Book and the Author

In 2001, the 9/11 attacks awoke the world to the military-style threat of Islamism. Due to the White House, the nationality of fifteen Saudis among the nineteen suicide bombers remained cast in shadows. In this exceptional tour-de-force, Craig Unger meticulously pieces together the US role in the birth of modern terrorism by relying on research and interviews with those who would prefer to deny the truth.

The acclaimed account of the link between modern terrorism and Saudi and corporate greed whose first UK publisher cancelled for fear of libel, and which several online retailers dared not stock.

‘An excellent read.’—Sunday Times

‘A notably intelligent piece of investigative reporting which lights the blue touch-paper.’—Observer

‘Craig Unger has done America and the world a huge favor by clearly and precisely documenting how the Bush inner circle is in the very deep pockets of the brutal Saudi dictators.’—Michael Moore, Director of Fahrenheit 9/11 ‘A forensic examination.’—Daily Telegraph

‘Very powerful… a chilling and meticulously researched account of the Bush-Saudi relationship. It’s a damning indictment of how personal and financial interests can overshadow national security.’—Guardian, book of the week

‘Unger’s meticulously researched book raises troubling questions about the ties between the Bush family and the Saudi royal family, especially in the aftermath of 9/11. It’s a provocative read that challenges conventional narratives.’—New York Times

‘Craig Unger’s House of Bush, House of Saud is a compelling and disturbing account of the intertwining interests of two powerful families. While some may dismiss it as conspiracy theory, the depth of research demands attention.’—The Washington Post

‘Craig Unger’s House of Bush, House of Saud is a gripping and unsettling exploration of the ties between two of the world’s most powerful families. It’s a sobering reminder of how personal and financial interests can shape global events.’—Los Angeles Times

‘None can match this judicious, clearly written and superbly researched analysis of Saudi venality and its corrupting effects on American politics.’—Irish Times

‘Craig Unger’s House of Bush, House of Saud is a provocative and deeply researched account of the Bush-Saudi nexus. It’s a sobering reminder of the complexities of global power dynamics.’—The Times

‘Hardhitting.’—Independent on Sunday

‘An explosive book.’—Scotland on Sunday

‘Out to nail the scions of executive privilege: All the President's Men and Boys...well-sourced... cool, calm and collected.’ Times Higher Education Supplement

‘A narrative as chilling as it is gripping.’ (Belfast) Telegraph

‘A meticulously documented account of the symbiotic relationship between two of the world’s most powerful families. It’s a chilling read.’—Independent

‘Unger’s book is a riveting and deeply researched exposé that sheds light on the shadowy connections between the Bush family and the Saudi elite. It’s a sobering reminder of the complexities of global power dynamics.’—The Sydney Morning Herald

‘Unger’s book is a meticulously documented and deeply disturbing account of the Bush-Saudi nexus. It’s a must-read for anyone interested in the intersection of politics, oil, and terrorism.’—The Boston Globe

‘Craig Unger’s House of Bush, House of Saud is a provocative and eye-opening investigation into the ties that bind American politics and Saudi wealth. It’s a must-read for anyone interested in the hidden forces behind global events.’—Le Monde

‘Unger’s book is a meticulously researched and deeply unsettling account of the Bush-Saudi relationship. It’s a powerful critique of the intersection of politics, oil, and terrorism.’—Der Spiegel

‘Craig Unger’s House of Bush, House of Saud is a provocative and deeply researched account of the intricate ties between the Bush family and the Saudi royal family. While some of its claims are controversial, the book provides valuable insights into the intersection of oil, politics, and terrorism.’—Foreign Affairs

‘Unger’s work is a compelling addition to the literature on U.S.-Saudi relations. Its focus on the personal and financial connections between the Bush family and the Saudi elite offers a unique perspective on the geopolitical landscape of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.’—The Journal of American History

‘Craig Unger’s House of Bush, House of Saud is a meticulously researched and thought-provoking exploration of the Bush-Saudi nexus. It raises important questions about the role of personal relationships in shaping international policy.’—Middle East Journal

‘Unger’s book is a bold and controversial examination of the ties between the Bush family and the Saudi royal family. While some may question its conclusions, the depth of research and the questions it raises make it a valuable contribution to the field.’—International Affairs

‘Unger’s investigative prowess shines in this exposé, which delves into the murky world of oil, politics, and terrorism. A must-read for those interested in the hidden forces shaping global events.’—Publishers Weekly

Chapter One

The Great Escape

It was the second Wednesday in September 2001, and for Brian Cortez, a desperately ill twenty-one-year-old man in Seattle, Washington State, the day he had long waited for. Two years earlier, Cortez had been diagnosed with congestive heart failure,1 and since then his prognosis had become even worse: he suffered from dilated cardiomyopathy, a severe swelling of the heart for which the only permanent solution is a transplant.

Cortez had been on the official heart transplant waiting list for months. Now, thanks to an accident in Anchorage, Alaska, an organ was finally available. The transplant team from the University of Washington Medical Center chartered a plane to Alaska to retrieve it as quickly as possible. The human heart can last about eight hours outside the body before it loses its value as a transplanted organ. That was the length of time the medical team had to remove it from the victim’s body, take it to the Anchorage airport, fly approximately fifteen hundred miles from Anchorage to Seattle, get it to the University of Washington Medical Center, and complete the surgery.

Sometime around midnight, the medical team boarded a chartered jet and flew back with its precious cargo. They passed over the Gulf of Alaska and the Queen Charlotte Islands, and finally, Vancouver, Canada. Before they crossed the forty-ninth parallel and reentered U.S. airspace, however, something unexpected happened.

Suddenly, two Royal Canadian Air Force fighters were at the chartered plane’s side. The Canadian military planes then handed it off to two U.S. Air Force F/A-18 fighter jets, which forced it to land.2 Less than twenty-four hours earlier, terrorists had hijacked four airliners in the worst atrocity in American history, crashing two of them into New York’s World Trade Center and one into the Pentagon. Nearly three thousand people were dead. America was grounded. Brian Cortez’s new heart was eighty miles short of its destination, and time was running out.3

Cortez’s medical team was not alone in confronting a crisis caused by the shutdown of America’s airspace. The terrorist attacks had grounded all commercial and private aviation throughout the entire United States for the first time in history. Former vice president Al Gore was stranded in Austria because his flight to the United States was canceled. Former president Bill Clinton was stuck in Australia. Major league baseball games were postponed. American skies were nearly as empty as they had been when the Wright brothers first flew at Kitty Hawk. America was paralyzed by terror, and for forty-eight hours, virtually no one could fly.

No one, that is, except for the Saudis.

At the same time that Brian Cortez’s medical team was grounded, Prince Bandar bin Sultan bin Abdul Aziz, the Saudi Arabian ambassador to the United States, was orchestrating the exodus of more than 140 Saudis scattered throughout the country. They included members of two families: One was the royal House of Saud, the family that ruled the kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and which, thanks to the country’s vast oil reserves, was without question the richest family in the world. The other family was the Sauds’ close friends and allies, the bin Ladens, who in addition to owning a multibillion-dollar construction conglomerate had spawned the notorious terrorist Osama bin Laden.

At fifty-two, Prince Bandar had long been the most recognizable figure from his country in America. Widely known as the Arab Gatsby, with his trimmed goatee and tailored double-breasted suits, Bandar was the very embodiment of the contradictions inherent in being a modern, jet-setting, Western-leaning member of the royal House of Saud.

Flamboyant and worldly, Bandar entertained lavishly at his spectacular estates all over the world. Whenever he was safely out of Saudi Arabia and beyond the reach of the puritanical form of Islam it espoused, he puckishly flouted Islamic tenets by sipping brandy and smoking Cohiba cigars. And when it came to embracing the culture of the West, Bandar outdid even the most ardent admirers of Western civilization—that was him patrolling the sidelines of Dallas Cowboys football games with his friend Jerry Jones, the team’s owner. To militant Islamic fundamentalists who loathed pro-West multibillionaire Saudi royals, no one fit the bill better than Bandar.

And yet, his guise as Playboy of the Western World notwithstanding, deep in his bones, Prince Bandar was a key figure in the world of Islam. His father, Defense Minister Prince Sultan, was second in line to the Saudi crown. Bandar was the nephew of King Fahd, the aging Saudi monarch, and the grandson of the late king Abdul Aziz, the founder of modern Saudi Arabia, who initiated his country’s historic oil-for-security relationship with the United States when he met Franklin D. Roosevelt on the USS Quincy in the Suez Canal on February 14, 1945.4 The enormous royal family in which Bandar played such an important role oversaw two of the most sacred places of Islamic worship, the holy mosques in Medina and Mecca.

As a wily international diplomat, Bandar also knew full well just how precarious his family’s position was. For decades, the House of Saud had somehow maintained control of Saudi Arabia and the world’s richest oil reserves by performing a seemingly untenable balancing act with two parties who had vowed to destroy each other.

On the one hand, the House of Saud was an Islamic theocracy whose power grew out of the royal family’s alliance with Wahhabi fundamentalism, a strident and puritanical Islamic sect that provided a fertile breeding ground for a global network of terrorists urging a violent jihad against the United States.

On the other hand, the House of Saud’s most important ally was the Great Satan itself, the United States. Even a cursory examination of the relationship revealed astonishing contradictions: America, the beacon of democracy, was to arm and protect a brutal theocratic monarchy. The United States, sworn defender of Israel, was also the guarantor of security to the guardians of Wahhabi Islam, the fundamentalist religious sect that was one of Israel’s and America’s mortal enemies.

Astoundingly, this fragile relationship had not only endured but in many ways had been spectacularly successful. In the nearly three decades since the oil embargo of 1973, the United States had bought hundreds of billions of dollars of oil at reasonable prices. During that same period, the Saudis had purchased hundreds of billions of dollars of weapons from the United States. The Saudis had supported the United States on regional security matters in Iran and Iraq and refrained from playing an aggressive role against Israel. Members of the Saudi royal family, including Bandar, became billionaires many times over, in the process quietly turning into some of the most powerful players in the American market, investing hundreds of billions of dollars in equities in the United States.5 And the price of oil, the eternal bellwether of economic, political, and cultural anxiety in America, had remained low enough that enormous gas-guzzling SUVs had become ubiquitous on U.S. highways. During the Reagan and Clinton eras the economy boomed.

The relationship was a coarse weave of money, power, and trust. It had lasted because two foes, militant Islamic fundamentalists and the United States, turned a blind eye to each other. The U.S. military might have called the policy “Don’t ask, don’t tell.” The Koran had its own version: “Ask not about things which, if made plain to you, may cause you trouble.”6

But now, in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, the ugly seams of the relationship had been laid bare. Because thousands of innocent people had been killed and most of the killers were said to be Saudi, it was up to Bandar, ever the master illusionist, to assure Americans that everything was just fine between the United States and Saudi Arabia. Bandar had always been a smooth operator, but now he and his unflappable demeanor would be tested as never before.

Bandar desperately hoped that early reports of the Saudi role had been exaggerated—after all, Al Qaeda terrorist operatives were known to use false passports. But at 10 p.m. on the evening of September 12, about thirty-six hours after the attack, a high-ranking CIA official—according to Newsweek magazine, it was probably CIA director George Tenet—phoned Bandar at his home and gave him the bad news:7 Fifteen of the nineteen hijackers were Saudis. Afterward, Bandar said, “I felt as if the Twin Towers had just fallen on my head.”

Public relations had never been more crucial for the Saudis. Bandar swiftly retained PR giant Burson-Marsteller to place newspaper ads all over the country condemning the attacks and dissociating Saudi Arabia from them.8 He went on CNN, the BBC, and the major TV net-works and hammered home the same points again and again: The alliance with the United States was still strong. Saudi Arabia would support America in its fight against terrorism.

Prince Bandar also protested media reports that referred to those involved in terrorism as “Saudis.” Asserting that no terrorists could ever be described as Saudi citizens, he urged the media and politicians to refrain from casting arbitrary accusations against Arabs and Muslims. “We in the kingdom, the government and the people of Saudi Arabia, refuse to have any person affiliated with terrorism to be connected to our country,” Bandar said.9 That included Osama bin Laden, the perpetrator of the attacks, who had even been disowned by his family. He was not really a Saudi, Bandar asserted, for the government had taken away his passport because of his terrorist activities.

But Osama bin Laden was Saudi, of course, and he was not just any Saudi. The bin Ladens were one of a handful of extremely wealthy families that were so close to the House of Saud that they effectively acted as extensions of the royal family. Over five decades, they had built their multibillion-dollar construction empire thanks to their intimate relationship with the royal family. Bandar himself knew them well. “They’re really lovely human beings,” he told CNN. “[Osama] is the only one … I met him only once. The rest of them are well-educated, successful businessmen, involved in a lot of charities. It is—it is tragic. I feel pain for them, because he’s caused them a lot of pain.”10

Like Bandar, the bin Laden family epitomized the marriage between the United States and Saudi Arabia. Their huge construction company, the Saudi Binladin Group (SBG), banked with Citigroup and invested with Goldman Sachs and Merrill Lynch.11 Over time, the bin Ladens did business with such icons of Western12 culture as Disney, the Hard Rock Café, Snapple, and Porsche. In the mid-nineties, they joined various members of the House of Saud in becoming business associates with former secretary of state James Baker and former president George H. W. Bush by investing in the Carlyle Group, a gigantic Washington, D.C.-based private equity firm. As Charles Freeman, the former U.S. ambassador to Saudi Arabia, told the Wall Street Journal, “If there were ever any company closely connected to the U.S. and its presence in Saudi Arabia, it’s the Saudi Binladin Group.”13

The bin Ladens and members of the House of Saud who spent time in the United States were mostly young professionals and students attending high school or college.14 Many lived in the Boston area, thanks to its high concentration of colleges. Abdullah bin Laden, a younger brother of Osama’s (At least four members of the extended bin Laden family are named Abdullah bin Laden—Osama’s uncle, a cousin, his younger brother, and his son), was a 1994 graduate of Harvard Law School and had offices in Cambridge, Massachusetts.15 Several bin Ladens had attended Tufts University, near Boston.16 Sana bin Laden had graduated from Wheelock College in Boston and organized a Saudi festival at the Children’s Museum in Boston.17 Two bin Ladens—Mohammed and Nawaf—owned units in the Flagship Wharf condominium complex in Charlestown Navy Yard on Boston Harbor.18

Some of the young, chic, sophisticated members of the family appeared even more westernized than Bandar. Wafah† Binladin, a twenty-six-year-old graduate of Columbia Law School, lived in a $6,000-a-month rented loft in New York’s fashionable SoHo19 and was considering pursuing a singing career. Partial to Manhattan nightspots such as Lotus, the Mercer Kitchen, and Pravda,20 she was in Geneva, Switzerland, at the time of the attack and simply did not return. Kameron bin Laden, a cousin of Osama’s in his thirties, also frequented Manhattan nightspots and spent as much as $30,000 in one day on designer clothes at Prada’s Fifth Avenue boutique.21 He elected to stay in the United States.

But half brother Khalil Binladin wanted to go back to Jeddah. Khalil, who had a Brazilian wife, had been appointed as Brazil’s honorary consul in Jeddah22 and owned a sprawling twenty-acre estate in Winter Garden, Florida, near Orlando.23 As for the Saudi royal family, many of them were scattered all over the United States. Some had gone to Lexington, Kentucky, for the annual September yearling auctions. The sale of the finest racehorses in the world had been suspended after the terrorist attacks on September 11, but resumed the very next day. Saudi prince Ahmed bin Salman bought two horses for $1.2 million on September 12.

Others felt more personally threatened. Shortly after the attack, one of the bin Ladens, an unnamed brother of Osama’s, frantically called the Saudi embassy in Washington seeking protection. He was given a room at the Watergate Hotel and told not to open the door.24 King Fahd, the aging and infirm Saudi monarch, sent a message to his emissaries in Washington. “Take measures to protect the innocents,” he said.25

Meanwhile, a Saudi prince sent a directive to the Tampa Police Department in Florida that young Saudis who were close to the royal family and went to school in the area were in potential danger.26

Bandar went to work immediately. If any foreign official had the clout to pull strings at the White House in the midst of a grave national security crisis, it was he. A senior member of the Washington diplomatic corps, Bandar had played racquetball with Secretary of State Colin Powell in the late seventies. He had run covert operations for the late CIA director Bill Casey that were so hush-hush they were kept secret even from President Ronald Reagan. He was the man who had stashed away thirty locked attaché cases that held some of the deepest secrets in the intelligence world.27 And for two decades, Bandar had built an intimate personal relationship with the Bush family that went far beyond a mere political friendship.

First, Bandar set up a hotline at the Saudi embassy in Washington for all Saudi nationals in the United States. For the forty-eight hours after the attacks, he stayed in constant contact with Secretary of State Colin Powell and National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice.28

Before the attacks, Bandar had been invited to come to the White House to meet with President George W. Bush on September 13 to discuss the Middle East peace process.29 Even though the fifty-five-year-old president and he were, roughly speaking, contemporaries, Bandar had not yet developed the same rapport with the younger Bush that he had enjoyed for decades with his father. Bandar and the elder Bush had participated in the shared rituals of manhood—hunting trips, vacations together, and the like. Bandar and the younger Bush were well-known to each other, but not nearly as close.

On the thirteenth, the meeting went ahead as scheduled. But in the wake of the attacks two days earlier, the political landscape of the Middle East had drastically changed. A spokesman for the Saudi embassy later said he did not know whether repatriation was a topic of discussion.

But the job had been started nonetheless. Earlier that same day, a forty-nine-year-old former policeman turned private investigator named Dan Grossi got a call from the Tampa (Florida) Police Department. Grossi had worked with the Tampa force for twenty years before retiring, and it was not particularly unusual for the police to recommend former officers for special security jobs. But Grossi’s new assignment was very much out of the ordinary.

“The police had been giving Saudi students protection since September eleventh,” Grossi recalls. “They asked if I was interested in escorting these students from Tampa to Lexington, Kentucky, because the police department couldn’t do it.”

Grossi was told to go to the airport, where a small charter jet would be available to take him and the Saudis on their flight. He was not given a specific time of departure, and he was dubious about the prospects of accomplishing his task. “Quite frankly, I knew that everything was grounded,” he says. “I never thought this was going to happen.” Even so, Grossi, who’d been asked to bring a colleague, phoned Manuel Perez, a former FBI agent, to put him on alert. Perez was equally unconvinced. “I said, ‘Forget about it,’” Perez recalls. “Nobody is flying today.”

The two men had good reason to be skeptical. Within minutes of the terrorist attacks on 9/11, the Federal Aviation Administration had sent out a special notification called a NOTAM—a notice to airmen—to airports all across the country, ordering every airborne plane in the United States to land at the nearest airport as soon as possible, and prohibiting planes on the ground from taking off. Initially, there were no exceptions whatsoever. Later, when the situation stabilized, several airports accepted flights for emergency medical and military operations—but those were few and far between.

Nevertheless, at 1:30 or 2 p.m. on the thirteenth, Dan Grossi received his phone call. He was told the Saudis would be delivered to Raytheon Airport Services, a private hangar at Tampa International Airport. When he arrived, Manny Perez was there to meet him.

At the terminal a woman laughed at Grossi for even thinking he would be flying that day. Commercial flights had slowly begun to resume, but at 10:57 a.m., the FAA had issued another NOTAM, a reminder that private aviation was still prohibited. Three private planes violated the ban that day, in Maryland, West Virginia, and Texas, and in each case a pair of jet fighters quickly forced the aircraft down. As far as private planes were concerned, America was still grounded.

Then one of the pilots arrived. “Here’s your plane,” he told Grossi. “Whenever you’re ready to go.”

What happened next was first reported by Kathy Steele, Brenna Kelly, and Elizabeth Lee Brown in the Tampa Tribune in October 2001. Not a single other American paper seemed to think the subject was newsworthy.30

Grossi and Perez say they waited until three young Saudi men, all apparently in their early twenties, arrived. Then the pilot took Grossi, Perez, and the Saudis to a well-appointed ten-passenger Learjet. They departed for Lexington at about 4:30 p.m.31

“They got the approval somewhere,” said Perez. “It must have come from the highest levels of government.”32

“Flight restrictions had not been lifted yet,” Grossi said. “I was told it would take White House approval. I thought [the flight] was not going to happen.”33

Grossi said he did not get the names of the Saudi students he was escorting. “It happened so fast,” Grossi says. “I just knew they were Saudis. They were well connected. One of them told me his father or his uncle was good friends with George Bush senior.”34

How did the Saudis go about getting approval? According to the Federal Aviation Administration, they didn’t and the Tampa flight never took place. “It’s not in our logs,” Chris White, a spokesman for the FAA, told the Tampa Tribune. “… It didn’t occur.”35 The White House also said that the flights to evacuate the Saudis did not take place.

According to Grossi, about one hour and forty-five minutes after takeoff they landed at Blue Grass Airport in Lexington, a frequent destination for Saudi horse-racing enthusiasts such as Prince Ahmed bin Salman. When they arrived, the Saudis were greeted by an American who took custody of them and helped them with their baggage. On the tarmac was a 747 with Arabic writing on the fuselage, apparently ready to take them back to Saudi Arabia. “My understanding is that there were other Saudis in Kentucky buying racehorses at that time, and they were going to fly back together,” said Grossi.

With just three Saudis on it, the Tampa flight was hardly the only mysterious trip under way. All over the country, members of the extended bin Laden family, the House of Saud, and their associates were assembling in various locations. At least seven other planes were available for their transportation. Officially, the FBI says it had nothing to do with the repatriation of the Saudis. “I can say unequivocally that the FBI had no role in facilitating these flights one way or another,” says Special Agent John Iannarelli.36

Bandar, however, characterized the role of the FBI very differently. “With coordination with the FBI,” he said on CNN, “we got them all out.”

Meanwhile, the Saudis had at least two of the planes on call to repatriate the bin Ladens. One of them began picking up family members all across the country. Starting in Los Angeles on an undetermined date, it flew first to Orlando, Florida, where Khalil Binladin, a sibling of Osama bin Laden’s, boarded.37 From Orlando, the plane continued to Dulles International Airport outside Washington, before going on to Logan Airport in Boston on September 19, picking up members of the bin Laden family along the way.

As the planes prepared for takeoff at each location across the country, the FBI repeatedly got into disputes with Rihab Massoud, Bandar’s chargé d’affaires at the Saudi embassy in Washington. “I recall getting into a big flap with Bandar’s office about whether they would leave without us knowing who was on the plane,” said one former agent who participated in the repatriation of the Saudis.38 “Bandar wanted the plane to take off and we were stressing that that plane was not leaving until we knew exactly who was on it.”

In the end, the FBI was only able to check papers and identify everyone on the flights. In the past, the FBI had been constrained from arbitrarily launching investigations without a “predicate”—i.e., a strong reason to believe that an individual had been engaged in criminal activities. Spokesmen for the FBI assert that the Saudis had every right to leave the country.

Meanwhile, President Bush was in Washington working full-time at the White House to mobilize a global antiterror coalition. On Friday, September 14, a dozen ambassadors from Arab nations—Syria, the Palestinian Authority, Algeria, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, and the Persian Gulf states—met at Prince Bandar’s home in McLean, Virginia, to discuss how they would respond to Bush’s new policies.39 Bandar himself had pledged his support for the war on terror and, perhaps most important, vowed that Saudi Arabia would help stabilize the world oil markets. In a breathtaking display of their command over the oil markets, the Saudis dispatched 9 million barrels of oil to the United States. As a consequence, the price instantly dropped from $28 to $22 per barrel.40

On Tuesday, September 18, at Logan Airport, a specially reconfigured Boeing 727 with about thirty first-class seats had been chartered by the bin Ladens and flew five passengers, all of them members of the bin Laden family, out of the country from Boston.

The next day, September 19, President Bush met with the president of Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim country, and with the foreign ministers of Russia and Germany. His speechwriting team was also working on a stirring speech to be delivered the next day, officially declaring a global war on terror. “Our war on terror … will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped, and defeated,” he vowed.41

Meanwhile, the plane that had originated in Los Angeles and gone to Orlando and Washington, another Boeing 727, was due to touch down at Boston’s Logan International Airport.42

At the time, Logan was in chaos. The two hijacked planes that had crashed into the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers had departed from Logan. The airport was reeling from criticism that its security failures had allowed the hijackings to take place, and exceptional measures were now being taken. Several thousand cars were towed from the air-port’s parking garages. “We didn’t know if they were booby-trapped or what,” said Tom Kinton, director of aviation at Logan.43

Even though the Federal Aviation Administration had allowed commercial flights to resume on September 13, because of various security issues, Logan did not reopen until September 15, two days later.44 Even then, air traffic resumed slowly.

Then, in the early afternoon of September 19, a call came into Logan’s Emergency Operations Center saying that the private charter aircraft was going to pick up members of the bin Laden fami1y.45 Both Kinton and Virginia Buckingham, the head of the Massachusetts Port Authority, which oversees Logan, were incredulous. “We were in the midst of the worst terrorist act in history,” Kinton said. “And here we were seeing an evacuation of the bin Ladens!”

Like Kinton, Virginia Buckingham was stunned that the bin Laden family was being spirited out of the country. “My staff was told that a private jet was arriving at Logan from Saudi Arabia to pick up fourteen members of Osama bin Laden’s family living in the Boston area,” she later wrote in the Boston Globe.46 “‘Does the FBI know?’ staffers wondered. ‘Does the State Department know? Why are they letting these people go? Have they questioned them?’ This was ridiculous.”*

Yet there was little that Logan officials could do. Federal law did not give them much leeway in terms of restricting an individual flight. “So bravado would have to do in the place of true authority,” wrote Buckingham.47

“Again and again, Tom Kinton asked for official word from the FBI. ‘Tell the tower that plane is not coming in here until somebody in Washington tells us it’s okay,’ he said.”

As the bin Ladens were about to land, the top brass at Logan Airport did not know what was going on. The FBI’s counterterrorism unit should have been a leading force in the domestic battle against terror, but here it was not even going to interview the Saudis.

“Each time,” Buckingham wrote, “the answer was the same: ‘Let them leave.’ On September 19, under the cover of darkness, they did.”

Of course, the vast majority of the Saudis on those planes had nothing whatsoever to do with Osama bin Laden. The bin Laden family itself had expressed “the strongest denunciation and condemnation of this sad event, which resulted in the loss of many innocent men, women, and children, and which contradicts our Islamic faith.”48 And a persuasive case could be made that it was against the interests of the royal family and the bin Ladens to have aided the terrorists.

On the other hand, this was the biggest crime in American history. A global manhunt of unprecedented proportions was under way. Thousands of people had just been killed by Osama bin Laden. Didn’t it make sense to at least interview his relatives and other Saudis who, inadvertently or not, may have aided him?

Moreover, Attorney General John Ashcroft had asserted that the government “had a responsibility to use every legal means at our disposal to prevent further terrorist activity by taking people into custody who have violated the law and who may pose a threat to America.”49 All over the country Arabs were being rounded up and interrogated. By the weekend after the attacks, Ashcroft, to the dismay of civil libertarians, had already put together a package of proposals broadening the FBI’s power to detain foreigners, wiretap them, and trace money-laundering to terrorists. Some suspects would be held for as long as ten months at the American naval base in Guantánamo, Cuba.

In an ordinary murder investigation, it is commonplace to interview relatives of the prime suspect. When the FBI talks to subjects during an investigation, the questioning falls into one of two categories. Friendly subjects are “interviewed” and suspects or unfriendly subjects are “interrogated.” How did the Saudis get a pass?

And did a simple disclaimer from the bin Laden family mean no one in the entire family had any contacts or useful information whatsoever? Did that mean the FBI should simply drop all further inquiries? At the very least, wouldn’t family members be able to provide U.S. investigators with some information about Osama’s finances, people who might know who him or might be aiding Al Qaeda?

Moreover, national security experts found it hard to believe that no one in the entire extended bin Laden family had any contact whatsoever with Osama. “There is no reason to think that every single member of his family has shut him down,” said Paul Michael Wihbey, a fellow at the Institute for Advanced Strategic and Political Studies.50

Vincent Cannistraro, a former CIA counterterrorism chief, told the New Yorker, “I’ve been following the bin Ladens for years, and it’s easy to say, ‘We disown him.’ Many in the family have. But blood is usually thicker than water.”51

In fact, Osama was not the only bin Laden who had ties to militant Islamic fundamentalists. As early as 1979, Mahrous bin Laden, an older half brother of Osama’s, had befriended members of the militant Muslim Brotherhood and had, perhaps unwittingly, played a key role in a violent armed uprising against the House of Saud in Mecca in 1979, which resulted in more than one hundred deaths.

One Saudi who had married into the extended bin Laden family was widely reported to be an important figure in Al Qaeda and was tied to the men behind the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, to the October 2000 bombing of the USS Cole, and was alleged to have funded a Philippine terrorist group.

Another Saudi, who boarded one of the earliest planes to leave the United States, had won the attention of foreign investigators for possible terrorist connections. According to an international press agency, the Saudi had business connections in a Latin American city thought to to be a center for training terrorists, including members of the Hezbollah movement.

How is it possible that Saudis were allowed to fly even when all of America, FBI agents included, was grounded? Had the White House approved the operation—and, if so, why?

When Bandar arrived at the White House on Thursday, September 13, 2001, he and President Bush retreated to the Truman Balcony, a casual outdoor spot behind the pillars of the South Portico that also provided a bit of privacy. Over the years, any history made on the Truman Balcony had transpired in informal conversation. In 1992, nine years earlier, President Bush’s father, George H. W. Bush, had walked out on the balcony with Boris Yeltsin, the first democratically elected president of Russia, to celebrate the end of the Cold War. In 1993, after First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton put an end to smoking in the White House, Bill Clinton would sometimes retreat there to smoke a cigar in a celebratory moment, as he did after the United States rescued a soldier in Bosnia.

This occasion may have marked the beginning of a new era, but Bandar and President Bush had nothing to celebrate. Thousands of Americans were dead. They had been killed in a terrorist operation largely run by Saudis. Nonetheless, the two men each lit up a Cohiba and began to discuss how they would work together in the war on terror. Bush said that the United States would hand over any captured Al Qaeda operatives to the Saudis if they would not cooperate. The implication was clear: the Saudis could use any means necessary—including torture—to get the suspects to talk.52

But the larger points went unspoken. The two men were scions of the most powerful dynasties in the world. The Bush family and its close associates—the House of Bush, if you will—included two presidents of the United States; former secretary of state James Baker, who had been a powerful figure in four presidential administrations; key figures in the oil and defense industries, the Carlyle Group, and the Republican Party; and much, much more. As for Bandar, his family effectively was the government of Saudi Arabia, the most powerful country in the Arab world. They had hundreds of billions of dollars and the biggest oil reserves in the world. The relationship was unprecedented. Never before had a president of the United States—much less, two presidents from the same family—had such close personal and financial ties to the ruling family of another foreign power.

Yet few Americans realized that these two dynasties, the Bush family and the House of Saud, had a history dating back more than twenty years. Not just business partners and personal friends, the Bushes and the Saudis had pulled off elaborate covert operations and gone to war together. They had shared secrets that involved unimaginable personal wealth, spectacular military might, the richest energy resources in the world, and the most odious crimes imaginable.

They had been involved in the Iran-contra scandal, and in secret U.S. aid in the Afghanistan War that gave birth to Osama bin Laden. Along with then Vice President Bush, the Saudis had joined the United States in supporting the brutal Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein for seven full years after knowing that he had used weapons of mass destruction. In the private sector, the Saudis had supported George W. Bush’s struggling oil company, Harken Energy, and in the nineties they made common cause with his father by investing in the Carlyle Group. In the 1991 Gulf War, the Saudis and the elder Bush had fought side by side. And now there was the repatriation of the bin Ladens, which could not have taken place without approval at the highest levels of the executive branch of President George W. Bush’s administration.

Only Bush and Bandar know what transpired that day on the Truman Balcony. But the ties between the two families were so strong that allowing the Saudis to leave America would not have been difficult for Bush. It would also have been in character with a relationship in which decisions were often made through elaborate and contrived deniability mechanisms that allowed the principals to turn a blind eye to unseemly realities and to be intentionally “out of the loop.”

The ties between the two families were an open secret that in some ways was as obvious as the proverbial elephant in the living room. Yet at the same time it was somehow hard to discern even for the most seasoned journalists. Perhaps that was because the relationship had been forged all over the globe and arced across different eras—from the Reagan-Bush years to the Clinton administration to the presidency of George W. Bush. To understand its scope and its meaning, one would have to search through tens of thousands of forgotten newspaper stories, read scores of books by journalists and historians, and study myriad “Secret” classified documents and the records of barely remembered congressional probes of corporate intrigue and Byzantine government scandals. One would have to journey back in time to the birth of Al Qaeda at the terrorist training camps during the Afghanistan War. One would have to study the Iran-Iraq War of the eighties, the 1991 Gulf War, and the Iraq War of 2003. One would have to try to deduce what had happened within the corporate suites of oil barons in Dallas and Houston, in the executive offices of the Carlyle Group, in the Situation Room of the White House, and in the grand royal palaces of Saudi billionaires. One would have to interview scores of politicians, oil executives, counterterrorism analysts, CIA operatives, and businessmen from Washington and Saudi Arabia and Texas. One would have to decipher brilliantly hidden agendas and purposefully murky corporate relationships.

Finally, one would have to put all this information together to shape a continuum, a narrative in which the House of Bush and the House of Saud dominated the world stage together in one era after another. Having done so, one would come to a singular inescapable conclusion: namely, that, horrifying as it sounds, the secret relationship between these two great families helped to trigger the Age of Terror and give rise to the tragedy of 9/11.

Chapter Two

The Houston-Jeddah Connection

ON A WARM AUGUST night in 2002, James R. Bath, a little-known Texas businessman, opens the door to the front of his ranch in Liberty, a town of eight thousand people on the Trinity River outside Houston. His house is framed by trees silhouetted against a moonlit Texas sky.

About six feet tall, trim and balding, Bath mingles a wry, folksy Texas charm with some of the machismo of a veteran jet fighter pilot. The combination has served him well in cultivating relationships with some of the great Texas power brokers of the last generation—from former governor John Connally to the Bush family.

There are many ways to tell the story of the events leading up to September 11 and the Iraq War of 2003, and Bath is hardly the most important person through whom to view them. However, his very obscurity carries its own significance. Bath happens to have served as the intentionally low-profile middleman in a passion play of sorts, the saga of how the House of Saud and its surrogates first courted the Bush family.

Bath is disarmingly hospitable as he whips up a late-night dinner and recounts the story of the birth of the Houston-Jeddah connection in the 1970s. A native of Natchitoches, Louisiana, he moved to Houston in 1965 at the age of twenty-nine to join the Texas Air National Guard. In the late sixties, after working for Atlantic Aviation, a Delaware-based company that sold business aircraft, he moved to Houston and went on to become an airplane broker on his own. Sometime around 1974—he doesn’t recall the exact date—Bath was trying to sell a F-27 turboprop, a sluggish medium-range plane that was not exactly a hot ticket in those days, when he received a phone call that changed his life.

The voice on the other end belonged to Salem bin Laden, heir to the great Saudi Binladin Group fortune. Then only about twenty-five, Salem was the eldest of fifty-four children of Mohammed Awad bin Laden, a brilliant engineer who had built the multibillion-dollar construction empire in Saudi Arabia.*

Bath not only had a buyer for a plane no one else seemed to want, he had also stumbled upon a source of wealth and power that was certain to pique the interest of even the brashest Texas oil baron. Bath flew the plane to Saudi Arabia himself—no easy task since the aircraft could only do about 240 knots an hour—and ended up spending three weeks in Jeddah, where he befriended two key figures in the new generation of young Saudi billionaires.1 One of them was Salem bin Laden. In addition, Salem introduced Bath to his family and friends, including Khalid bin Mahfouz, also about twenty-five, who was the heir to the National Commercial Bank of Saudi Arabia, the biggest bank in the kingdom.

Salem was of medium height, outgoing, and thoroughly Western in his manner, says Bath. Bin Mahfouz was taller—about six feet—rail thin, relatively quiet and reserved. One associate says that if he had not known bin Mahfouz was a Saudi billionaire, he would have mistaken him for a biker straight out of a Harley-Davidson ad.

Bath immediately took to the two young men. “I like the Saudi mentality. They like guns, horses, aviation, the outdoors,” he said. “We had a lot in common.”

In many ways, bin Mahfouz† and bin Laden were Saudi versions of the well-heeled good old boys whom Bath knew so well. “In Texas, you’ll find the rich carrying on about being just poor country boys,” he says.2 “Well, these guys were masters of playing the poor, simple bedouin kid.”

Poor, they were not. Salem and Khalid were both poised to take over the companies started by their billionaire fathers. In fact, they had almost identical family histories. Their fathers, Mohammed Awad bin Laden and Salem bin Mahfouz respectively, had both originally come from the Hadramawt, an oasislike valley in rugged, mountainous eastern Yemen. Both men were uneducated and poor—bin Laden was a brilliant but illiterate bricklayer who never even learned to sign his name—and had traveled the same 750-mile trek by foot. In Jeddah, the commercial capital of Saudi Arabia, they made their fortunes off the hajj, the sacred pilgrimages to the great mosques in Mecca and Medina, bin Laden through construction and bin Mahfouz through currency exchange.

In 1931, Salem’s father, Mohammed Awad bin Laden, had formed what eventually became the Saudi Binladin Group as a modest general-contracting firm that first became known for building roads, including a stunning highway with precipitous hairpin turns between Jeddah and the resort city of Taif. Ambitious and highly disciplined, the elder bin Laden advanced his cause by submitting below-cost bids on palace construction projects, including palaces for members of the royal family.3 His shrewdest innovation was to build a ramp to the palace bedroom of the aging and partially paralyzed King Abdul Aziz.4 Subsequently, the king made him the royal family’s favorite contractor for palaces and major governmental infrastructure projects.

As a result of this growing friendship, in 1951, bin Laden won the contract to build one of the kingdom’s first major roads, running from Jeddah to Medina. Eventually, he became known as the king’s private contractor. “He was a nice man, very well liked by the royals,” says an American oil executive who knew Mohammed Awad bin Laden. “He had the reputation of a doer, of getting things done.”

The most prestigious and lucrative prize given by the royal family to the bin Ladens was for the kingdom’s biggest roads5 and exclusive rights to all religious construction, including $17 billion in contracts to rebuild the holy sites at Medina and Mecca,6 which carried enormous iconic significance. In the center of the Grand Mosque of Mecca was the Kaaba, the holiest place to worship in all of Islam. Legend has it that the Kaaba was built after God instructed the prophet Abraham to build a house of worship, and the Archangel Gabriel gave Abraham a black stone, thought to be a meteorite, which was placed in the north-east corner of the Kaaba. “If there is one single image that signifies the Muslim world, it is that of the hajj being performed in the Kaaba,” says Adil Najam, a professor at Boston University.7 “[Rebuilding these sites] would be the Western equivalent of restoring the Statue of Liberty, Mount Rushmore, and the Lincoln Memorial—multiplied by a factor of ten.”

During the same period that Mohammed Awad bin Laden was cementing his ties with the royal family, Salem bin Mahfouz was using similar methods to woo King Abdul Aziz. After leaving the Hadramawt in 1915, bin Mahfouz had worked in various capacities for the wealthy Kaaki family of Mecca for thirty-five years, finally winning a partnership in the Kaakis’ lucrative currency exchange business.8 Because charging interest was condemned by the Koran as usury, at the time Saudi Arabia merely had money changers instead of a domestic banking industry. But bin Mahfouz went to the royal family and argued that Saudi Arabia would never be self-sufficient until the kingdom had a bank. Subsequently, bin Mahfouz won a license that allowed him to establish the National Commercial Bank of Saudi Arabia, the first bank in the kingdom.

By the early sixties, the bin Mahfouzes and the bin Ladens had made extraordinarily successful transitions from the tribal, Wild West-like Hadramawt in Yemen to the far more commercially sophisticated world of Jeddah. Since they were outsiders—both families were Yemenites—the bin Ladens and the bin Mahfouzes did not have the tribal allegiances that other Saudis had,9 and it was easy for the royal family to build them into billionaire allies who did not bring with them the political baggage other Saudis may have had. Consequently, the two great merchant families had virtual state monopolies in construction and banking.

In effect, the Saudi Binladin Group was on its way to becoming a Saudi equivalent of Bechtel, the huge California-based construction and engineering firm.10 Likewise, bin Mahfouz had begun to build the National Commercial Bank into the Saudi version of Citibank, paving the way for it to enter the era of globalization.

Knowing full well the value of being close to the royal family in Saudi Arabia, Salem bin Laden and Khalid bin Mahfouz sought to have similar relationships in the United States. With Bath tutoring them in the ways of the West, they started coming to Houston regularly in the mid-seventies. Salem came first, buying planes and construction equipment for his family’s company.11 He bought houses in Marble Falls on Lake Travis in central Texas’s Hill Country and near Orlando, Florida.12 He started an aircraft-services company in San Antonio, Bin-laden Aviation, largely as a vehicle for managing his small fleet of planes.13 He converted a BAC-111, a British medium-size commercial liner, for his own personal use, and for fun he flew Learjets, ultralights, and other planes around central Texas.

There were days that began in Geneva, continued in England, and ended up in New York.14 Salem flew girlfriends over the Nile to see the Pyramids. “He loved to fly, and spent more time trying to entertain himself than anyone I know,” says Dee Howard,15 a San Antonio engineer who converted several aircraft for bin Laden, including the $92-million modification of a Boeing 747-400 for King Fahd’s personal use,16 the biggest such conversion in the world. The spectacularly outfitted jumbo jet boasted its own private hospital and was said to make Air Force One look modest by comparison.

From Texas to England, most Westerners who knew the bin Ladens found them irresistible. “Salem was a crazy bastard—and a delightful guy,” says Terry Bennett, a doctor who attended the family in Saudi Arabia.17 “All the bin Ladens filled the room. It was like being in the room with Bill Clinton or someone—you were aware that they were there. They may have had the normal human foibles, but they were good for their word and generous to a fault.”

Salem loved music, the nightlife, and entertaining guests at dinner parties by playing guitar and singing “Deep in the Heart of Texas.”18 But Khalid bin Mahfouz was more reserved. “Khalid was a banker first and always acted as a banker should,” remembers Bath. “He was extremely intelligent and quick to assess things.”

For the most part, bin Laden and bin Mahfouz eschewed the gaudy public extravagance of sheikhs such as Mohammed al-Fassi, who in 1979 painted his Beverly Hills mansion in a color that evoked rotting limes and redid the statuary so that the genitals appeared more lifelike.19 Still, this was Texas. Bigger was better, and bin Mahfouz and bin Laden observed the prevailing mores. As they became entrenched in Texas in the seventies, bin Mahfouz bought an enormous, rambling $3.5-million faux château,20 later known as Houston’s Versailles,21 in the posh River Oaks section of Houston. He also purchased a four-thousand-acre ranch in Liberty County on the Trinity River near James Bath’s ranch.

These men, billionaires from a fundamentalist theocratic monarchy, had arrived in a wide-open American city where strip clubs and churches were often side by side, and they fit right in. “They loved the ranch and they loved the country life,” says Bath. “There was a real affinity between Texas and life in the kingdom. Khalid would come out to the ranch with the family and the kids, to ride horses, shoot guns, fireworks. They’d been going to England forever. But Texas—there was the novelty.”

Bin Laden and bin Mahfouz were not the only Saudis who started making the Saudi Arabia-Texas commute. Saudi arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi operated a small fleet of Boeing 727s for his private use.22* In 1970, Prince Bandar, later the ambassador on the Truman Balcony with President Bush, trained at Perrin Air Force Base near Sherman, Texas, as a fighter pilot23 and became a daring acrobatic pilot who delighted in entertaining VIPs with his audacious aerial stunts. Joining them were the future king, then Crown Prince Fahd bin Abdul Aziz al-Saud; construction magnate Sheikh Abdullah Baroom; and others. “There were more private planes for the Saudis than many airlines have,” says one pilot who flew for Salem bin Laden.24 “It was quite an operation. Everyone had big airplanes and we flew whatever had wings.”

Houston offered them a glimpse of a rapidly approaching Saudi future. As late as 1974, the tallest building in the Saudi capital, Riyadh, was a mere water tower,25 but downtown Houston was already studded with gleaming skyscrapers. At home, the Saudis shopped in ancient markets known as souks, but in Houston, the extravagantly modern Galleria shopping mall had just opened.26 Saudi Arabia was still a feudal desert kingdom where people lacked the professional skills and bureaucratic infrastructure to build a modern economy. Houston, by contrast, had gigantic energy-industry law firms—Baker Botts; Vinson, Elkins and Connally; Fulbright & Jaworski—that greased the wheels of America’s enormous oil industry so it could easily navigate the corridors of power in Washington. In many ways, Riyadh and Houston could scarcely have been more dissimilar; yet these differences were precisely what attracted the Saudis to Texas and catalyzed a chain of events over the next three decades that would change global history.

In part, it was oil that drew the two cultures together. Its history in Texas dated to January 10, 1901, when a handful of wildcatters in Beaumont, Texas, about sixty miles from Houston, drilled away until mud mysteriously bubbled up from the ground and several tons of pipe abruptly shot upward with enormous force. A few minutes later, as workmen began to inspect the damage, another geyser of oil erupted from thirty-six hundred feet under a salt dome.27 The wildcatters had hoped to bring in fifty barrels a day.28 Instead, the legendary Spindle-top gusher brought in as many as one hundred thousand.29 The Texas oil boom had begun.

Before long, Houston’s Ship Channel had grown into a twenty-mile stretch of refineries constituting one of the great industrial complexes in the world, where hundreds and hundreds of towers and massive spherical tanks spewed smoke and steam, eerily illuminating the ghostly sky like a brightly lit Erector set. More than a quarter of all the oil used in the United States was refined there. Part of the complex, the Exxon Mobil plant in Baytown, is the biggest oil refinery in the world, producing more than half a million barrels a day.30

By contrast, oil was not even discovered in Saudi Arabia until 1938,31 and even then, and for more than a generation afterward, control of the vast Saudi resources remained heavily influenced by the United States thanks to lucrative concessions granted to Aramco (the Arabian American Oil Company), a consortium of giant American oil companies and the Saudis.³²* In the early seventies, however, just before bin Laden and bin Mahfouz struck out for Texas, the world of oil underwent a dramatic change. Oil production in the United States had already peaked in 1970 and was beginning an inexorable decline at a time when more people drove more miles in bigger cars that burned more gas. Baby boomers had come of age and were driving. An elaborate suburban car culture had grown up all over the United States. There were Corvettes and Mustangs, muscle cars such as the Trans Am, and drive-in restaurants and shopping malls. The volume of America’s imported oil nearly doubled—from 3.2 million barrels a day in 1970 to 6.2 million a day in 1973.33 Saudi Arabia’s share of world exports sky-rocketed from 13 percent in 1970 to 21 percent in 1972.

Saudi Arabia’s transformation from an underdeveloped backwater to one of the richest countries in the world was under way. In October 1973, just after the Arab-Israeli war, OPEC—the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries—a heretofore impotent consortium of oil-rich nations, abruptly became a genuine cartel capable of driving the price of oil up more than 300 percent. Oil, they had discovered, could be used as a weapon. Suddenly, Saudi Arabia took on the position Texas itself had once had and became the swing oil producer for the great industrial nations of the world. The biggest transfer of wealth in human history was under way. Hundreds of billions of dollars in oil revenues poured into the Saudi kingdom.34 The Saudis were drowning in petrodollars.

Not surprisingly, most Americans don’t have fond memories of theSaudi ascendancy in the seventies. With the embargo, the price of gas in the United States jumped from 38 cents a gallon in 1973 to $1.35 in 1981.35 Soaring inflation, high interest rates, and long gas lines soon followed. A nationwide speed limit of fifty-five miles per hour was imposed in the interests of fuel efficiency. Government bureaucracies were established to reduce energy consumption.

Houston, however, benefited from the newfound Saudi wealth more than any other city in the country. All over the United States, architectural firms cut back because of the recession, but in Houston, CRS Design Associates more than doubled its payroll—thanks to huge contracts from the Saudis.36 Superdeveloper Gerald Hines built gleaming skyscrapers in downtown Houston designed by the likes of Philip Johnson and I. M. Pei—financed, it was whispered, with Saudi riyals. Petrodollars flowed into Houston’s Texas Commerce Bank, thanks to Arab clients. Saudi companies bought drill bits and pipes and lubricant in Houston.37 The price of oil was over $30 a barrel and looked as if it would never fall—and while the rest of the country had to pay the price, Texas oil producers also enjoyed the higher revenues. At last, Houston was on the map of international café society. Local socialites hung out at Tony’s Restaurant on Westheimer Road, taking a prominent table with Princess Grace, Mick Jagger, fashion designer Bill Blass, or whichever well-known houseguest had flown in for the week.38 In all, more than eighty companies in Houston developed strong business relationships with the Saudis.39 It was even said that Houston was becoming to the Saudis what New York is to Israel and the Jews40—another home half a world away.

Like the Israelis, the Saudis had one overwhelming need that they sought in this new alliance-defense. For all its newfound wealth, the House of Saud was more vulnerable militarily than ever. A feudal desert monarchy that lacked the infrastructure of a modern industrial nation, the kingdom had more than fifteen hundred miles of coastline to defend. Its oil and gas facilities provided numerous high-value targets. Iran regularly sponsored riots during the pilgrimages to Mecca and provided support to Shiite extremists in Saudi Arabia.41 Iraq, with which it shares a border, was a threat. Across the Red Sea, Sudan was a hospitable host to extremists. Other troublesome neighbors included Yemen, Oman, and Jordan. Saudi Arabia was vast—it is about a quarter the size of the United States—but it had to be defended by a population that, at the time, was under 6 million people, three-quarters of whom were women, children, and elderly.42

Tausende von E-Books und Hörbücher

Ihre Zahl wächst ständig und Sie haben eine Fixpreisgarantie.

Sie haben über uns geschrieben: