Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: John Donald

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Serie: The Stewart Dynasty in Scotland

- Sprache: Englisch

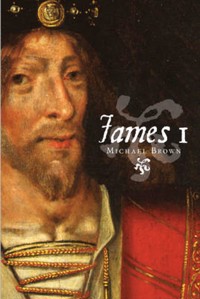

Conditioned by a childhood surrounded by the rivalries of the Stewart family, and by eighteen years of enforced exile in England, James I was to prove a king very different from his elderly and conservative forerunners. This major study draws on a wide range of sources, assessing James I's impact on his kingdom. Michael Brown examines James's creation of a new, prestigious monarchy based on a series of bloody victories over his rivals and symbolised by lavish spending at court. He concludes that, despite the apparent power and glamour, James I's 'golden age' had shallow roots; after a life of drastically swinging fortunes, James I was to meet his end in a violent coup, a victim of his own methods. But whether as lawgiver, tyrant or martyr, James I has cast a long shadow over the history of Scotland.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 565

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

JAMES I

This short run edition first published in 2015 byJohn Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House10 Newington RoadEdinburghEH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 1994

ISBN 978 1 788853 64 4

Copyright © Michael Brown, 1994, 2000

The right of Michael Brown to be identified as the author of thiswork has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designsand Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available from the British Library

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Bell & Bain, Glasgow

Contents

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Preface

List of Illustrations

Maps and genealogical tables

Introduction. ‘Our Lawgiver King’

1 Fortune’s Wheel

2 The Destruction of the Albany Stewarts

3 The Albany Stewart Legacy

4 ‘The King’s Rebels in the North Land’

5 ‘A Fell, A Farseeing Man’: Royal Image and Reality

6 ‘A Tyrannous Prince’

7 The Covetous King

8 The Assassination of James I

9 Tyrant and Martyr: James I and the Stewart Dynasty

Bibliography

Index

Foreword

In a now famous passage of his History, written shortly before 1521, John Mair extolled the virtues of James I, claiming that he would not give precedence over the first James to any one of the Stewarts. For Mair, the apostle of Anglo-Scottish union and writing at almost a century’s distance, King James’s virtues were self-evident: he had spent his formative years observing English royal government at close quarters, he broke the power of overmighty noble familes in Scotland, and he brought firm, even-handed justice to his kingdom. This last achievement had already been stressed by Abbot Walter Bower within a few years of the King’s death; writing during the political chaos of the early 1440s, Bower recalled James I as ‘our lawgiver king’, a ruler who had established firm peace within the kingdom. According to Bower, the people were settled ‘in peaceful prosperity’, because the king ‘wisely expelled feuds from the kingdom, kept plundering in check, stopped disputes and brought enemies to agreement’.

This view of James, with only a few modifications, has persisted down to the twentieth century. E.W.M. Balfour-Melville’s biography of the king, which appeared in 1936, praised James for his parliamentary legislation, and indeed seems to have regarded the summoning of the three estates as the yardstick of good royal government. King James’s darker side is played down; thus his annihilation of his Albany Stewart relatives is justified on the ground that ‘high rank was no defence for lawlessness’, his pre-emptive strikes against other members of his nobility are spoken of with approval, and his assassination in February 1437 ‘caused an immediate revulsion of feeling’ in his favour, with nobles and people ‘lamenting the death of an upright and energetic king’. Balfour-Melville’s eulogy of King James, though modified by Professor Duncan, Dr Wormald and Dr Grant, and to some extent challenged by Dr Nicholson, is still with us. James I is a man to be admired, as much, it seems, for endeavouring to confer the benefits of Lancastrian constitutionalism on a backward Scotland as for anything else.

Dr Michael Brown presents a radically different view of the king in this book, arguing that James’s success or failure as a ruler can be judged only by studing his relations with the Scottish nobility throughout the thirteen years of his personal rule. These men and their predecessors had, after all, run the country not only during James’s long residence in England and France, but for more than half a century before 1424, when successive Stewart kings had been little more than primus inter pares amongst the higher nobility, sometimes not even that. Dr Brown, together with earlier writers, emphasises the shock of the change in the style of government following James I’s return to Scotland in 1424, ‘a king unleashed’ in Dr Nicholson’s memorable phrase. But for many of his Scottish subjects, the shock was not a pleasant one, nor can it be assumed, as Dr Brown points out, that the masterful James I’s efforts to emulate Henry V of England north of the border produced an appropriate or satisfactory governmental style. And the king who employed as a trusted counsellor James Douglas of Balvenie and Abercorn, one of the most blatant extortionists in the pre-1424 period, rather damages his credentials as the purveyor of even-handed justice and enforcer of law and order.

Contemporaries, even the loyal Walter Bower, had their doubts about James I, as Dr Brown shows; Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini, the future Pope Pius II, described the king as ‘greedy, passionate, and vindictive’, and John Shirley, while abhorring James’s assassination, saw James I as a ‘tyrannous prince’ whom his subjects had tried to arrest in 1436. Dr Brown skilfully balances Bower’s lawgiver against Shirley’s tyrant, and provides the most detailed description of James I’s murder and its vitally important aftermath.

In the last analysis, it may be that James I is still widely admired because the forceful style of kingship which he introduced, although violently rejected in 1437, would be adopted by his son and would prevail in less than twenty years. Historians enjoy dwelling on success and seeking to explain it. But perhaps even John Mair, that admirer of strong kingship, had secret doubts about it all; for immediately after his eulogy of James I in his History, he comments that ‘many Scots are accustomed, though not openly, to compare the Stewarts to the horses in the district of Mar, which in youth are good, but in their old age bad’. Mair goes on to reject this view of the dynasty as a whole; but perhaps he privately thought that it applied specifically to James I.

Norman MacdougallSeries Editor

Acknowledgements

First, I would like to acknowledge the financial assistance provided to me, during the writing of my doctoral thesis and further research for this book, by the British Academy and by the Departments of Medieval and Scottish History at the University of St Andrews. I am grateful for the help I received from the libraries and repositories which I have used in the course of my research.

A number of people have given me particular support and help during the writing of this book. Mr A.B. Webster of the Department of History at the University of Kent provided invaluable general and specific advice arising from my research, while Dr Christine McGladdery shared with me the results of her research into the reign of James II, now in print as the only full biography of James I’s heir. I take great pleasure in also acknowledging the contribution of Dr Steve Boardman, whose researches into both the feud and into the reigns of Robert II and Robert III have left their mark on this book as have his general views on late medieval Scotland expressed (often forcefully) during numerous long lunchtimes. In witnessing the smooth and rapid production of the typescript, I have joined the long list of Scottish historians in admiration of the skill and enthusiasm of Mrs Margaret Richards.

Over the past six years Dr Norman Macdougall has been a model supervisor and editor. His patience, encouragement and knowledge have kept me on track, while the hospitality of Norman, Simone and Bonnie have sustained the inner man during the same period.

I also owe a large debt of gratitude in a number of capacities to my wife Dr Margaret Connolly of the Department of English, University College, Cork, whose own research into John Shirley and her edition of The Dethe of the Kynge of Scotis have aided my own work, but it is for a host of other reasons that I record my thanks. Finally, I wish to thank my parents for their moral and financial support.

Preface

The return of James I to his kingdom in 1424 after eighteen years in English captivity has long been seen as a major turning point in the history of Scotland. James’s thirteen-year personal rule marked a return to active monarchy after almost half a century of weak kings and delegated authority. Moreover, in his brief period of power in Scotland, James would influence not only his son James II, but all his successors. The line of aggressive rulers of Scotland working as adults to extend their influence and increase their status both within their kingdom and abroad, which lasted until the death of James V, can be traced directly back four generations to the first James.

However, despite this significance, James I remains, in Professor Donaldson’s words, ‘this most enigmatic of the Scottish kings’.1 This enigma lies partly in the variety of roles and characteristics ascribed to James by men of the same generation. He was lawgiver, defender of the common weal and bringer of a golden age of peace, as well as poet, athlete and builder of palaces. However, at the same time, James was accused of being covetous, vindictive and tyrannical, a new Pharaoh oppressing his people. The confused impression which this creates of James is compounded by the dramatic contrasts of success and failure which the king experienced in his short life, culminating in his murder at the hands of a group of his subjects.

The only full-length attempt to resolve the contradictions of James I’s contemporary reputation was made over half a century ago by E.W.M. Balfour-Melville.2 Although Balfour-Melville’s study remains the best secondary source of information for James’s lifetime, his view of the King is derived chiefly from the legislation of parliament and the financial records of royal government, both of which are examined in detail. As a result James is presented as a legislator and reformer whose main ambitions were embodied in a package of laws designed to increase the importance of both King and parliament.

This perception of the King, although based on early references to James as a lawgiver, has been called into question by more recent discussions of James I’s reign by Dr Grant and Dr Wormald and, especially, by Professor Duncan. Duncan’s pamphlet, James I King of Scots, also concentrates on royal legislation and relations with parliament, but Duncan concludes ‘that there was no master-plan to re-vitalise the Scottish constitution’.3 Instead he sees James’s relations with parliament as being the result of external pressures on the king, and his legislation as a ‘hand-to-mouth response’ to these pressures. However, in showing the limitations of Balfour-Melville’s view of the king, Duncan of necessity concentrates on the practices of central government and parliament and space prevents him from providing anything like a full alternative impression of James I’s character and rule.

The only other recent studies of James have appeared as part of general overviews of late medieval Scottish politics. Dr R.G. Nicholson sees James I as ‘a king unleashed’ in Scotland: The Later Middle Ages and paints a picture of his rule as an ‘autocracy that was sometimes cantankerous and vindictive’, dependent on ‘the strong personality of the king’.4 This view of James as a disruptive force within Scotland is also pressed, though in different terms, in J.M. Wormald’s article ‘Taming the Magnates?’ and in A. Grant’s chapter on ‘Kings and Magnates’ in Independence and Nationhood.5 Dr Wormald sees the king’s ‘vindictiveness’ being channelled against the wider Stewart family which posed a dynastic threat to James, while Dr Grant emphasises the more general arbitrariness of the king both for his own and his supporters’ benefit. While all these perceptions of the reign give a less favourable impression of James I and view the king’s ‘zeal’ for law and order as essentially cynical and practical, none is of sufficient length or detail to analyse in depth the period from 1424 to 1437.

As a result there are still basic problems about the aims and achievements of James. It is the purpose of this book to attempt to resolve some of these problems, especially concerning the king’s government of Scotland during his personal rule between 1424 and 1437. As the work of Grant and Wormald has stressed, in a de-centralised kingdom such as Scotland, the king’s authority depended principally on his relations with a small group of major nobility holding power in the local areas of the realm.

James I’s political management of this group closest to the crown in terms of blood and resources is of special significance and lies at the heart of this book. In 1424 the Scottish magnates effectively formed the government of Scotland. They were a group accustomed to function without royal leadership. For eighteen years James, their nominal king, had been in foreign captivity, and for almost all of the twenty-two years before that, royal authority had rested in the hands of a series of lieutenants. Therefore, James’s return in itself represented a drastic change in Scottish politics; and the change was exacerbated by his experience of English government. James spent his formative years in the kingdom with the most centralised system of government in western Europe, and had observed at first hand the activities of the most aggressive sovereign of the age, Henry V of England. His English experience clearly moulded James’s view of the means and ends of royal power.

A major theme of this book is the contrast and conflict between James’s perception of the trappings and practice of kingship and the expectations and experience of his chief subjects. The aims of James I need to be assessed continually with this group in mind, as the leading magnates possessed the local influence to place active and passive checks on royal actions. Moreover, the nature of Scottish politics since the 1370s meant that the political community in 1424 was dominated by descendants of Robert II in a kind of Stewart family firm. This made the forceful intervention of quasi-royal magnates in central politics a real possibility in James’s reign. It is no coincidence that the two most important political events of the period between 1424 and 1437 were the king’s attack on his nearest kinsmen, the Albany Stewarts, in 1425, and his murder in a plot led by his uncle, Walter, Earl of Atholl, the last surviving son of Robert II. Nobles such as Albany, Mar, Atholl and Douglas clearly overshadowed the king on his return in many areas of Scotland, and James’s attitude to this power is probably the best starting point for any clear understanding of the nature and course of his reign.

Within this general theme there are a number of specific questions about the reign, most importantly the events which determined the extent of James’s authority and its abrupt end, the execution of Murdac, Duke of Albany and his kin, and James’s own assassination. How did the king, without an obvious power-base within Scotland on his return, effect a ‘royalist revolution’ by assembling support for his destruction of the Albany Stewarts, the family which had dominated Scottish politics for over thirty years?6 Equally, how was James himself killed in the midst of his own household despite the image of royal success and power he had established, and why did his assassins, who paid horribly for their actions, believe that they could have any long term prospect of victory?

In connection with these two pivotal events of the reign, the aims and nature of James’s kingship are examined. The doubling of royal landed resources, and the growth of royal prestige, which accrued to James following his elimination of Albany, clearly changed royal relations with the remaining magnates. It also gave James the opportunity to heighten consciously the status of the crown and begin the pattern of royal expenditure on architecture, artillery and on lavish personal display which was followed by his successors. The security and stability of this apparent royal dominance need also to be studied against the background of continued royal aggression by the king, leading to political tensions with his subjects.

As a whole, therefore, this book is intended to provide a framework of Scottish politics for the thirteen years of James’s active reign beyond the series of royal attacks on individual nobles described by the chroniclers, or the lists and acts of parliaments. In this way it is hoped that more light will be shed on the complexities of James I as a man, and on his true achievements as king.

NOTES

1 A. Grant, ‘Duncan, James I, a review’, in Scottish Historical Review, lxvii (1988), 82-3.

2 E.W.M. Balfour-Melville, James I King of Scots (London, 1936).

3 A. A.M. Duncan, James I King of Scots 1424-1437, University of Glasgow Department of Scottish History Occasional Papers (Glasgow, 1984).

4 R.G. Nicholson, Scotland, The Later Middle Ages, Edinburgh History of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1974), 317.

5 J.M. Wormald, ‘Taming the Magnates?’, in K.J. Stringer (ed.), Essays on the Nobility of Medieval Scotland (Edinburgh, 1985), 270-280; A. Grant, Independence and Nationhood: Scotland 1306-1469, New History of Scotland (London, 1984), 171-99.

6 R.G. Nicholson, Scotland, The Later Middle Ages, 287.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1 Charles of Orléans in the Tower of London

2 The Bass Rock

3 Dumbarton Castle

4 Henry V of England

5 Charles VII of France

6 Lincluden Collegiate Church

7 Linlithgow Palace: the East Front

8 St Bride’s Chapel, Douglas: the tomb of James 7th Earl of Douglas

9 Inverlochy Castle

10 Dunbar Castle

11 Kildrummy Castle

12 Perth: the North Inch and the Blackfriars

MAPS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES

MAPS

1 James I in France

2 Scotland in 1424

3 The Highlands and Islands in the Reign of James I

4 Locations of Royal Acts (1424-1437)

TABLES

1 The House of Stewart (1371-1437)

2 The Descendants of Robert III

3 The Albany Stewarts

4 The Black Douglases

5 The Kennedies of Dunure

Introduction‘Our Lawgiver King’1

Who was James I? In an age when government depended on the individual ability of the king, the character and quality of the ruler was bound to have a great impact on the course of his reign. In the first part of the fifteenth century this was certainly true. The mental feebleness of Henry VI of England and of his grandfather, Charles VI of France, had disastrous consequences for their subjects, while the successful reigns of England’s Henry V and Charles VII of France stemmed from their very different styles of kingship. In Scotland the age and infirmity of Robert II and Robert III, James’s grandfather and father, had deprived the kingdom of royal leadership in the opening years of the Stewart dynasty. Even against this background, however, the first James, King of Scots, left a very deep impression on the minds of his subjects; and to understand his brief but vital years of power, it is essential to gain an impression of the king himself and the reputation he was accorded by his early historians.

Likenesses of James are few and far between. Neither his anonymous sixteenth-century portrait nor the fresco depicting the king and his court which decorates the Cathedral Library of Siena can be considered as certain representations of James. The Sienese fresco was painted by the local artist Pinturrichio in the latter part of the fifteenth century and shows Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini, the future Pope Pius II, in conversation with the king during his 1435 embassy to Scotland. James is depicted as a white-bearded old man. As the king was to die at the age of forty-four, the image is of a stereotypical wise ruler, painted by an artist who would hardly be concerned with the accuracy of his likeness of James. In this respect the head and shoulders portrait of James I is more interesting. It is the first of a series of pictures showing the rulers of Scotland and appears more distinctive than the painting of the king’s immediate successors. James is shown with a strong bearded chin, long hair and large, though badly drawn eyes. The power of James’s eyes was referred to by one witness and these features may conceivably have come from earlier -and lost- depictions of the king and may give some idea of his physical appearance.

For a true portrait of the king, however, we are dependent on the written word and, at root, on the writing of one man. Walter Bower, abbot of the island community of Inchcolm, concluded his history of Scotland, the Scotichronicon, with an account of the king and the course of his reign. The abbot knew his subject well. Though never a close councillor of the king, Bower was an experienced observer of the exercise of power in Scotland. He had been a collector of royal taxation and a spokesman for the estates during the reign, and this first-hand knowledge allowed the abbot to build up strong impressions of his royal master.2 The evidence and opinions of such a man recalled within a decade of the king’s death provide us with a more reliable narrative about James I and his reign than exists for any of his immediate forerunners and predecessors. The words of Abbot Bower therefore dominate our image of James as King of Scots:

The king, was of medium height, a little on the short side, with a well-proportioned body and large bones, strong-limbed and unbelievably active, so that he . . . would challenge any one of his magnates of any size to wrestle with him.3

Bower describes James at the height of his physical powers on, or shortly after, his return to Scotland following eighteen years of English captivity. The king was then in his thirtieth year, but after a decade of the power and pleasures of monarchy, James was described by the future Pope Pius II, following their meeting, as ‘stocky and weighed down with fat’. However, he also retained an impression of the king’s ‘clear but piercing eyes’, a glimpse of the man inside the overweight frame.4 Bower’s description, however, is apt and not only in the image of the king wrestling with his magnates. The abbot draws a picture of a man constantly in motion and supports this view with a list of James’s accomplishments, indulged in ‘when he was at leisure from serious affairs’.

As well as wrestling these included the physical pursuits of hammer-throwing, jousting and archery, the latter an activity which James may have learned in England, the home of the longbow. The king certainly encouraged the practice of archery amongst his subjects for military reasons and may have led by example.5 James also enjoyed less martial pursuits, ‘respectable games’ as Abbot Bower calls them, which according to another contemporary source included ‘paume’, a form of hand tennis, chess and ‘gaming at tables’.6 Bower was most impressed, though, with the musical skills of the king, ‘not just as an enthusiastic amateur’ but a master, ‘another Orpheus’ on a variety of instruments: the organ, the drum, the flute and especially the Irish harp or lyre. Men came from Ireland and England to admire this royal mastery.7

Bower completed his picture of the king’s gifts by listing his intellectual skills. Among them were accomplishments in liberal arts and mechanical subjects, a knowledge of scripture and, most interestingly, ‘eagerness’ in ‘literary composition and writing’.8 This is the earliest reference to James’s best-known gift. By the early sixteenth century, the king possessed a reputation as a poet. The chronicler, John Mair, wrote that ‘he showed the utmost ability’ in writing and that ‘he wrote an ingenious little book about the queen while he was yet in captivity and before his marriage’. The manuscript copy of this work from c. 1505 contains the inscription that ‘Heirefter follows the quair Maid be King James of Scotland the first Callit the kingis quair and maid quhen his maiestie wes in England’. The Kingis Quair was an autobiographical love poem and the only one of James’s writings which can be identified confidently. It contains a view of philosophy and fortune derived from Boethius and was dedicated to Gower and Chaucer by its author.9 If James did write the poem, then it reveals something of his intelligence and sophistication as well as a personal sensitivity not obvious in his public life.

The king clearly possessed something of the range of abilities described by Abbot Bower. However, to the abbot, the writings of the king probably appeared frivolous. He gave more weight to the serious study of the arts and philosophy. Bower presented James I as a philosopher king, a multi-talented Renaissance Prince; and both the abbot and later chroniclers ascribed his accomplishments to the king’s youth and early manhood as a captive of the English.10 James was kept in enforced idleness without political responsibility and developed his pursuits and tastes as a result. After all, it was to two English poets that The Kingis Quair was dedicated. English influences on the king were to be a recurring theme of the reign while, similarly, the energy which James showed in his private interests and his strength in physical pursuits were also elements in his control of the kingdom. The image of a king wrestling with his magnates could refer to more than just a healthy taste for exercise.

To Bower, James was, above all, an ‘outstanding ruler’, ‘a tower, a lion, a light, a jewel, a pillar and a leader’.11 At times the Scotichronicon presents the king as a Messiah, the words of the Prophet Isaiah being adapted to James’s return to Scotland as the saviour of his kingdom. The abbot saw his king as chosen by God. ‘Clearly the Lord was with him and with His help he was successful at everything he undertook’.12 The king was a man with a mission:

On the first day of your return to the kingdom . . . you spoke out in manly fashion: ‘If God spares me, gives me help and offers me at least the life of a dog, I shall see to it throughout my kingdom that the key . . .guards the castle and the thorn-bushes the cow’.13

The abbot saw the return of peace and order in fulfilment of his pledge as the greatest of James’s achievements, ending the ‘thieving, dishonest conduct and plundering’ that Bower claimed existed before the king established his authority. James was chiefly ‘our lawgiver king’, a ruler who made it possible for his subjects to receive justice. ‘There was no need to attend a court of magnates or bishops . . . under arms, since in his time’ the only weapon carried openly was ‘the royal spear, to which the honoured, streaming, heraldic banner was attached’.14 The hallmarks of this glorious reign were ‘peaceful fair-dealing’ and ‘energetic justice’.15

The people were . . . settled in peaceful prosperity safe from thieves, with happy hearts, calm minds and tranquil spirits, because the king wisely expelled feuds from the kingdom, kept plundering in check . . . and brought enemies to agreement.16

Abbot Bower, however, was aware of the methods used by the king. ‘Firm peace’ was based on fear of the king and his anger towards any who opposed his orders. ‘If anyone did oppose him, he immediately paid the penalty’.17 The Scotichronicon contains two examples of the king’s principles in action. One, the king’s savage treatment of a brutal robber, shows James in a strong but favourable light, but the other involves ‘a certain great nobleman, a near relative of the king’. This noble displeased James by quarrelling at court and the king had to be restrained from having his kinsman stabbed in the hand as a punishment. Unlike the story of the robber, this latter tale is not repeated by subsequent chroniclers and even Bower must have been aware that it shows a violent, even bloodthirsty side to the king’s nature which sat ill with the abbot’s praise.18 An episode which portrayed the king assaulting a kinsman was near the knuckle for James who, as we shall see, had a well-known and well-founded record of turning on his relatives. Elsewhere Bower showed his own ambivalence towards James’s execution of his cousin, the Duke of Albany, and it may even have been a pointed gesture to include another tale of king striking magnate.19 However, at the relevant point Bower is keen to present the king’s physical threat to the noble in a favourable light, quoting Seneca who said: ‘The man who is merciful to evil does damage to the good’.20

The abbot’s use of Seneca, the tutor of the Emperor Nero, as his authority is not without irony. Bower, though, saw James’s terrorisation of an unruly nobility as good kingship and criticised his predecessor, Robert III, as ‘a slack shepherd’ whose reign was plagued by disquiet owing to an ‘absence of fear’.21 However, to other contemporaries, James I’s approach to government was close to tyranny. Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini, the future Pope, calls the king ‘passionate, greedy and vindictive’, while the papal agent in London, writing about James’s death, likened the king to a new Pharaoh, oppressing his captive church and people.22

The other side of the coin to the strong but just king of the Scotichronicon is drawn most fully in an account of James’s murder, also written in the 1440s. The Dethe of the Kynge of Scotis was composed or translated by an Englishman, John Shirley, and far from being a ‘sadistic handbill’, shows a knowledge of detail concerning Scottish politics which must have come from a source close to events. The Dethe goes a long way towards presenting James as a ‘tyrannous prince’ who acted more for vengeance and ‘covetise . . . than for anny laweful cawse’.23 It contains, admittedly in the mouth of one of James’s murderers, Sir Robert Graham, the ringing statement that

I have thus slayne and delivered yow of so cruelle a tyrant, the grettest enemye that Scottes or Scotland myght have, consyderyng his unstaunchable covetise.24

Strong kingship could be tyranny and the judgement of Bower is not necessarily less partisan than the words of Sir Robert Graham. While Graham, the convicted regicide, was hardly impartial, the abbot was deliberately and overtly writing with hindsight, longing for ‘the golden age of peace’. ‘How can we . . . hold back our tears when we recall the old days of this most famous king’. ‘When he died, the honour and glory of Scots died too’. Writing from the ‘precarious state of the realm’ in the violent and unstable 1440s, the abbot may have seen James’s reign as the good old days and his peace worth having at any price, but even amidst the nostalgia of Bower there are signs that this was less the prevailing mood at the time.25

The abbot admitted that the king, whose qualities he idealised posthumously, was ‘appreciated but slightly at the time’ and suffered a ‘misguided failure of respect’ from his subjects.26 However, at times Bower himself suggests doubts about James’s policies. He softens the accusation of royal ‘covetise’, saying that the king was ‘disposed to the acquisition of possessions’, adding that as a result of royal demands for taxation, ‘the people began to mutter against the king’, until he altered his financial habits.27 Similarly James’s laws ‘would have served the kingdom well enough . . . if they had been kept’, suggesting that although a lawgiver, the king’s legislation was allowed to lapse.28 In general, too, the abbot showed a capacity to keep quiet about contradictions of his account provided by political crises such as Albany’s execution and the king’s own death. These qualifications combine to create an image of the ruler which sits ill with the abbot’s confident assertion about James’s success and the ‘happy hearts’ of his subjects.

There is therefore a contradiction within the Scotichronicon between the eulogy for James with which Bower concludes his work and the reservations about the king expressed in the main part of Book Sixteen. The general tone remains, however, very much in favour of the king and it is Bower’s strong, successful lawgiver which becomes the predominant image of James in subsequent generations. To many sixteenth-century Scottish historians, the king’s qualities, as described by the abbot, were an attractive model for kingship and James’s successes were, if anything, magnified.

In particular, for the chronicler John Mair writing before 1521, James I was a model king. ‘This man indeed excelled by far in virtue his father, his grandfather and his great-grandfather, nor will I give precedence over the first James to any one of the Stewarts.’29 Mair wrote in favour of a British union and consistently argued for strong, aggressive kingship in both England and Scotland. Against this background, the English-educated James I and the series of attacks which he launched on his magnates was a subject bound to receive Mair’s approval. Similarly, writing at the same time, Hector Boece calls James the ‘maist vertuous Prince that evir was afoir his dayis, richt iust in all his lyffe and scharp punysair of vice’.30

Both chroniclers leant heavily on Bower for their evidence on the reign and their views of the king, but they were less ambivalent in their attitudes to James I’s actions than fifteenth-century writers. From the sixteenth century onwards historians have proved to be much more ready to praise strong kingship and, after Mair and Boece, identified James as a model for this. By the latter part of the century both the strongly Protestant George Buchanan and the exiled Catholic bishop, John Lesley, could regard the king in a highly favourable light from their conflicting standpoints. The extreme royalist Lesley ended his account of the reign with a condemnation of James’s killers:

O happie realme! governit with sa kinglie a king; O cruel creatures, quha dang doune sa strang a stay piller, and uphold of the Realme! Thir traytoris, like howlets culd nocht suffir to sie the bricht lycht of sa mervellous vertue.31

By the end of the sixteenth century, James was held up as a good king and his reign as a ‘good thing’ for Scotland. However, in the midst of the accolades for James, the historians were uncomfortably aware of a lingering hostile tradition concerning the king. The tyrant was not completely laid to rest. Lesley said of James that ‘in the exercise of justice he appeiret mair seveir than becam a king’ and that ‘sum said that for justice he pretendet old iniuries’. Though Lesley dismissed this as ‘malicious invention and false detraction’ and praised the king’s ‘luve of justice’, the doubts about James still lingered on.32 Even Mair and Boece are not free from these questions, Mair including a strange tale that James said to the queen ‘that he would leave no man in Scotland save him who was her bed-fellow; and this can be no otherwise interpreted than that he had in mind to put to death his whole nobility’.33 Mair, like Lesley, protested the king’s innocence but the survival of such an extreme story of murderous royal intentions as well as the more recognisable portrayal of James as partisan and vindictive remain in jarring contrast to the beacon of the virtues they otherwise seek to present.

The complexities of the king’s reputation had formed within a decade of his death and showed a remarkable persistence. At their root lay the personal impact of the king himself on his subjects. In his thirteen-year personal rule, James aroused the strongest reactions of hostility and respect from Scots. From all accounts of the reign it is clear that James was a man of considerable powers and energy, completely committed to a strong and aggressive style of kingship. The conflicting views of the king as a tyrant oppressing his people and as a lawgiver establishing welcome peace represent, to some extent, the attitude of his subjects to his government. They are a gauge of the support and opposition his kingship met in Scotland. The king’s life and, most dramatically, the manner of his death at the hands of a group of his own subjects, created a legacy of divided opinions in which, ultimately, James could be regarded as either a bloody tyrant or a martyr for his people’s good.

NOTES

1Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.28, 1.15 of the Latin text.

2Scotichronicon, vol.8, Introduction, xiii-xvi; Bk. XVI Ch.9, l.29-30; Bk. XVI, Ch.23, l.14-20; A.P.S.. ii, 6, c.10; 20, c.1.

3Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.28, l.30-5.

4Copiale Prioratus Sanctiandree, ed. J.H. Baxter (Oxford, 1930), 284-5.

5Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.28, 1.35-39; Ch.30, 1.1-2; A.P.S., ii, 6, c.19.

6The Life and Death of James I of Scotland, Maitland Club (Glasgow, 1837), 54; M. Connolly, ‘The Dethe of the Kynge of Scotis: A New Edition’ in S.H.R, no. LXXI (1992), 47-69, 56, 59.

7Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.28, l.39-52; Ch.29.

8Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.30, 1.5-6.

9 J. Major, A History of Greater Britain, Scottish History Society (Edinburgh, 1892), Bk. V, Ch. 14; The Kingis Quair of James Stewart, ed. M. McDiarmid, 1-48, 117.

10Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.30, l.102-26.

11Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.29, l.39-42; Bk. XVI, Ch.38, l.30-1.

12Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.30, l.21-3; Ch.35, 1.63-70.

13Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.35, l.27-35.

14Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.35, l.53-9.

15Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.34, l.5-7.

16Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.34, l.1-4.

17Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.33, l.14-21.

18Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.33, l.21-64.

19Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.10, l.42-54.

20Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.33, l.65-8.

21Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.19, l.4-6.

22Copiale, 284-85; D. Weiss, ‘The Earliest Account of the Murder of James I of Scotland’ in E.H.R., 52 (1937), 479-91.

23James I Life and Death, 49; M. Connolly, ‘The Dethe of the Kynge of Scotis’, 51-2.

24James I Life and Death, 64; M. Connolly, ‘The Dethe of the Kynge of Scotis’, 66 . . .

25Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.1, l.1, 4-5; Ch.35, 1.1.

26Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.28, l.20-6; Ch.34’ 1.18-19.

27Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.9, 1.31-2; Ch.13, 1.1-4.

28Scotichronicon, vol.8, Bk. XVI, Ch.14, l.28-31.

29 Major, History, Bk. VI, Ch.9.

30The Chronicles of Scotland compiled by Hector Boece, translated into Scots by John Bellenden, 1531, Scottish Text Society (Edinburgh, 1938-41), Bk. XVII, Ch.9.

31Leslie’s Historie of Scotland, ed. E.G. Cody, Scottish Text Society, 4 vols (Edinburgh, 1884-95), Bk. C, Ch.45; G. Buchanan, The History of Scotland, trans. J. Aikman (Glasgow and Edinburgh, 1827-9), Bk. CII, Ch.42.

32Leslie’s Historie, Bk. C, Ch.44.

33 Major, History, Bk. VI, Ch.14.

1

Fortune’s Wheel

PRINCE AND STEWARD

In his autobiographical poem The Kingis Quair, James I of Scotland pictured himself at the mercy of Fortune and ‘hir tolter quhele’, which raised men from the depths to the heights of power and could equally cast them down again.1 For the first thirty years of his life James was very much a victim of circumstance. From his birth until he began to rule Scotland in person, he experienced drastic changes of fortune and was a pawn in both the complex manoeuvrings of his family in Scotland and the diplomacy of western Europe. For although he became the nominal King of Scots in 1406 at the age of twelve, James spent the first eighteen years of his reign as a prisoner of the English, an uncrowned king in frustrating exile. Despite this lack of personal power, it was in these three decades that the character and aims of James’s own rule were established and the king himself was subject to the influences which forged his personal tastes and ambitions.

James Stewart was the third son and the sixth or seventh child of Robert III and his queen, Annabella Drummond. He was born at Dunfermline in 1394, probably in late July, as his mother wrote to Richard II of England on 1 August complaining of ‘malade denfant’ following the birth of a son ‘a non Jamez’.2 The choice of the name James, which was to have such long-lasting consequences for the dynasty, was unusual, though it had been held previously in the Stewart family. Whether it was as a family name or in connection with St James’s day (25 July), it is clear that unlike his elder brothers, David and Robert, the new prince was given a name without royal precedent in Scotland.

However, as striking as the choice of his name was the timing of James’s birth. James was born much later after three of his sisters, Margaret, Mary and Elizabeth, who were all married before or shortly after James’s birth. He was also sixteen years younger than his eldest brother, David, while Robert, the second son, was probably approaching adulthood in 1394 as well.3 In addition, James was born to parents who had been married for twenty-seven years before his birth. His father was in his late fifties and his mother was at least forty in 1394.4

Although the age of James’s parents and the gap between the ages of the first group of children and the new prince is not unique, it may suggest special circumstances. If James’s brother Robert, who is last recorded in February 1393, died before July 1394 it would have left the royal house with only a single male heir in David, Earl of Carrick.5 In contrast the family of Robert, Earl of Fife, the next younger brother of the king and next in line to the throne, was well provided with heirs. By 1394 Fife not only had four adult sons but his heir, Murdac, had married in 1392 and by the time of James’s birth Murdac’s elder two sons, Robert and Walter, had been born.6 Thus, James’s birth may have been part of a deliberate attempt to strengthen the dynastic position of Robert III in relation to his brother.

The desire of Robert III to make his own branch of the Stewart family more secure against the interference of the Earl of Fife would fit in with the rivalry between the two men. This rivalry was the political legacy of their father, Robert II, the first Stewart king. His long and uncertain career led him to concentrate power in the hands of his immediate family. By the latter part of Robert’s reign his five sons held eight out of the fifteen Scottish earldoms among them.7 Although this accumulation of power within the Stewart family ensured that Robert II’s descendants would occupy the throne, the creation of a family firm dominating the nobility posed a serious problem for the exercise of royal authority by the senior Stewart line.

Of the younger sons of Robert II, three were to establish dynasties which dominated much of Scotland for the next half-century: Alexander, Earl of Buchan, the so-called ‘Wolf of Badenoch’, Walter, Earl of Atholl, the ‘old serpent’ of Scottish politics and, most importantly, Robert, Earl of Fife and Duke of Albany, the uncrowned ruler of Scotland for thirty years.8 All three lived to be over sixty and in their long careers amassed power and influence in various parts of Scotland. They and their families formed a group of royal magnates too close to the crown in terms of blood and resources to allow the early Stewart kings to rule with ease.

Robert III was the victim of this situation. He began his reign in 1390, already in political eclipse. Two years earlier he had been declared unfit to rule after a period as guardian for his father and this stigma clearly clouded his accession. Before he inherited the throne he was forced to endure a five-month delay and to change his name from the ill-omened John to make himself more acceptable. He dropped the name of the unfortunate Balliol king and took Robert, recalling the Bruce blood in his veins, his credentials to be king. More importantly, though, power remained in the hands of his able and aggressive younger brother, Robert, Earl of Fife, who acted as guardian.9

During the later 1390s, James’s role was simply as second in line to the throne. It seems reasonable to assume that he was brought up in the household of his mother, Queen Annabella. Although James was only seven when the queen died in 1401, she may have had some influence on her youngest son. At least one of her servants, her marshal, William Giffard, served James for the rest of his life, and the prince’s household may have been formed from that of his mother, perpetuating her own political views.10 In contrast to her husband, Robert III, who was famed most for his humility and dogged with ill-health, Annabella seems to have exerted considerable political influence. She reportedly ‘raised high the honour of the kingdom . . . by recalling to amity magnates and princes who had been roused to discord’ and clearly backed the interests of her sons and their right to exercise power.11

It may have been due in part to her efforts that her eldest son, David, was accorded an increased significance in the 1390s. The promotion of David culminated in his elevation to the title of Duke of Rothesay in 1398 and his appointment as lieutenant for his father for three years in January 1399.12 This grant of authority clearly reduced the influence of Robert of Fife and, although he had been made Duke of Albany at the same time as his nephew’s promotion, he had reason to worry that Rothesay’s lieutenancy was the prelude to his reign as King David III.

If Queen Annabella had been involved in Rothesay’s appointment, she did not live to see its conclusion. Her death at Scone at ‘harvest-time’ in 1401 began a period of rapidly changing fortunes for James and, with more fatal consequences, for his elder brother, Rothesay.13 The loss of Annabella’s support was to leave David dangerously isolated. As a young man exercising political power for the first time, Rothesay approached the problems of government in a way markedly different from that of his father and uncle. His more active and assertive rule saw him intervening in areas which had become the prerogatives of the major magnates.14 By early 1402 this had led him to alienate his own brother-in-law, Archibald, Earl of Douglas, the most powerful magnate in southern Scotland, and brought him close to direct conflict with his uncle, Albany. In this confrontation, Albany’s experience and connections proved decisive. Two of Rothesay’s own councillors, William Lindsay of Rossie and John Ramornie, treacherously arrested David and handed him over to Albany. Once Rothesay was in his uncle’s hands there could be little chance that Albany would release him to become king in the near future. Following a hastily convened meeting between Albany and the Earl of Douglas which sealed his fate, Rothesay was starved to death in his uncle’s castle of Falkland in March 1402. Two months later Albany and Douglas justified their actions to a general council of the realm, probably using the version of events employed by Bower. This argued that Rothesay was beyond control by wiser counsels after his mother’s death and was taken into custody to curb his ‘frivolity’.15

To James the events of 1402 clearly had a different meaning. It is hard to overestimate the impact of his brother’s death on James’s growing political awareness in the next four years. A perception of Rothesay’s fall very different to Bower’s was related a century later by Hector Boece. Boece had no doubt that Rothesay was starved to death and added that ‘he decessit with grete martyrdom; quhais body . . . kycht miraclis mony yeris eftir, quhill king lames the furst began to puneis this cruelte and fra thyns the miraclis cessitt’.16 The idea of Rothesay’s death as a ‘martyrdom’ may have originated as royal propaganda during James’s own reign, and the near-contemporary account of John Shirley portrays the events of 1402 as the first act in a blood feud between the royal Stewarts and their Albany cousins.17

James certainly retained a memory of his brother’s death which fuelled his hostility towards the Albany Stewarts during the attack on the family in 1425. The execution of the son and grandsons of Robert, Duke of Albany, was the main part of this royal vengeance but James also turned his anger on the gaolers of his brother, William Lindsay, and the keeper of Falkland in 1402, John Wright, who were deprived of their lands.18 The king’s activities over twenty years later indicate that, either in 1402 or subsequently, James was made aware of the circumstances and implications of his brother’s fall. The death of Rothesay may well have appeared as political ‘martyrdom’ and those responsible as virtual regicides. Rothesay was quite probably killed as lieutenant and heir to the throne acting in pursuit of the powers of his office. It also served as an example to James of the price of political failure in the attempt to increase the authority of the central government. During his personal reign, James feared and then suffered the same ‘martyrdom’ as his brother.

The fall of Rothesay also marked the beginning of James’s personal importance in Scottish politics. From 1402 James was the only surviving son of Robert III and heir to his throne. The king was in his sixties and known to be infirm. His acquiescence in Rothesay’s arrest suggests that he had limited political will. Therefore as James was only seven, the future of the crown was by no means certain. In France it was believed at the time that James’s highly ambitious brother-in-law, Archibald, Earl of Douglas, would gain the throne, but this gossip ignored Douglas’s captivity in England from late 1402 after his defeat at the battle of Homildon Hill.19 More realistic worries existed about the aims of Robert, Duke of Albany, who was now just one life away from the throne and was again in control of central government.

Worries about the future of the dynasty presumably lay behind the promotion of James in Scottish politics following the death of his brother. However, whereas Rothesay was given the status and power to enable him to exercise authority in the kingdom, James’s advancement appears initially to have been designed to secure the prince’s political survival. The chief element of this was the grant to James of the main Stewart lands held by his father in December 1404.20 These included the earldom of Carrick and the lordships of Kyle and Cunningham in Ayrshire and the neighbouring lordship of Renfrew, along with Bute, Arran and Knapdale. These estates were the heartlands of Robert III’s rule and were the area in which he spent most of his time. The lands were granted to James as a regality, to be held outside the authority of central government, and may have been designed as a secure landed base for their new lord should he have to struggle to regain influence in his kingdom. Although James never shared his father’s attachment to the south-west, he was to view his ‘principality’ as a source of support on his return to Scotland twenty years later.

In conjunction with the creation of an independent landed-base for the prince, there may have been a long-term plan to secure James’s safety by sending him to France. According to Bower, in 1406 the prince was ‘to be sent secretly . . . to the lord Charles, king of the French, so that once he had acquired good habits there he might when at the age of manhood come back to his homeland in greater safety’.21 Bower seems to be suggesting that James was to be sent abroad to avoid an Albany-dominated minority and, after 1402, there would have been an understandable reluctance to allow the last of Robert III’s sons to fall into the duke’s hands.

However, if this plan existed it does not fully explain James’s political role after 1402. The consequences of James’s promotion, although hardly aimed at wresting power from Albany, were not purely defensive. The titles of Earl of Carrick and Steward of Scotland clearly established James as heir to the throne and made him a focus for political ambitions. While Robert III concentrated on creating a royal power-base in Ayrshire, which was further cemented in 1404 by the marriage of his daughter, Mary, to his vassal, James Kennedy, the new Steward of Scotland was elsewhere.22 James’s later lack of interest in his south-western lands was probably because, despite his principality, he never resided in the area before 1406. His mother seems to have remained in the east and after 1402 James’s rare appearances are at Perth, Linlithgow and St Andrews.23

Certainly from late 1404 or early 1405 James was separate from his father. This physical separation was to lead to James’s first direct participation in Scottish politics. Although he was only ten in 1404, James’s heightened status gave him an increased importance in the hands of men associated with the king. However, as had happened in the case of his brother, the advancement of James was to prove to be simply a prelude to disaster, leading to the events of 1406 which would condemn him to eighteen years of English imprisonment.

In late 1404 or early 1405 James was handed over for safe-keeping to Bishop Henry Wardlaw of St Andrews. Wardlaw had been elected to his see by papal favour against the wishes of Albany, and this may have led him to associate with two of the king’s main supporters acting in pursuit of increased royal and personal influence.24 These men were Sir David Fleming of Biggar and Cumbernauld and Henry Sinclair, Earl of Orkney and Lord of Roslin in Lothian.

The ambitions of these men were not directed against Albany, who was preoccupied with his own position in central and northern Scotland, but were aimed towards establishing influence in the south-east of the kingdom. This area was effectively in a power-vacuum following the upheavals of the previous five years. The main local magnate, George Dunbar, Earl of March, had been involved in a conflict with Rothesay and was forfeited in 1400 to the advantage of his main rival, Archibald, 4th Earl of Douglas.25 Over the next two years Douglas stamped his authority on the area, waging a cross-border war on the Dunbars, who were supported by the English. Douglas’s empire-building was brought to an abrupt halt in late 1402 when he was defeated and captured at the battle of Homildon Hill by an English army assisted by Dunbar. Not only Douglas but a large number of nobles from Lothian and the borders were captured, leaving the area without active leadership in the years which followed.26

It was the absence of these men which seems to have allowed Fleming and Orkney to exercise increased influence in southern Scotland and in Anglo-Scottish relations. Fleming, in particular, seems to have played a major role in negotiations with England after May 1404, acting as one of two commissioners for the Scots in a meeting to clarify the truce in July of the same year.27 In addition, in August 1405, Fleming became Sheriff of Roxburghshire due to a rare direct intervention by the king.28 As an influential figure on the borders, Fleming was especially involved with both Bishop Wardlaw and the Earl of Orkney in taking an aggressive line against England during 1405. The rebellion of Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, against Henry IV of England presented the opportunity for this policy. By June 1405, Northumberland had been deserted by his English allies and turned to Scotland for help in retaining his lands and castles in the English marches, the most important of which was the town and stronghold of Berwick.29

Fleming, Orkney and Wardlaw were the men who provided Scottish backing for Northumberland. Orkney went south with Northumberland’s main accomplice, Lord Bardolph, and joined the rebel earl in Berwick.30 However, this only delayed Northumberland’s final flight over the border in early July 1405.31 The earl was received by Wardlaw ‘and other friends of the realm of Scotland’ at the border priory of Coldingham and then in St Andrews Castle. Northumberland’s relations with Wardlaw were clearly good as he left his grandson and heir, Henry, in the bishop’s care.32 Wardlaw’s custody of the young Henry Percy and of Prince James linked both the bishop and the heir to the throne to Fleming and Orkney’s foreign policy ambitions. The education of the Percy heir alongside James must have appeared to give official sanction to the English rebels and their presence in Scotland.

The domination of marcher politics by the clique around James provoked a reaction from the family which naturally expected to hold this position, the Black Douglases. In the absence of Archibald, Earl of Douglas, as an English captive, the family was headed by James Douglas, the earl’s younger brother. As warden of the marches in his brother’s place in 1405 James Douglas cannot have welcomed the powers of his office and family being usurped by Fleming and Orkney.33 The support given to Northumberland jeopardised hopes for the release of the Douglas earl and provoked English raids on Black Douglas lands in the borders. The aggrieved tone of James Douglas’s letter to Henry IV in late July 1405 may reflect his dissatisfaction about the situation on the borders at this point.34

Black Douglas resentment turned to open hostility over the issue of the release of Archibald, Earl of Douglas. The earl was allowed to return temporarily to Scotland in August 1405 to present a plan to exchange him for the Earl of Northumberland.35 However, this plan was foiled by Fleming, who, by warning the English earl, allowed him to flee to Wales where he formed an alliance with the rebel prince, Owain Glyn Dwr. Fleming’s action was clearly aimed against the Douglases and, according to the English chronicler, Thomas Walsingham, provoked open civil war in Scotland from late 1405.36

In such a crisis the possession of James by Fleming and his associates was a vital political weapon. The decision was taken to remove him from Wardlaw’s care and place him under the direct control of Sir David Fleming.37 Although Fleming had been in touch with the French government of Louis, duc d’Orléans, which gave backing to both Northumberland and the Welsh, in early 1406 Fleming was probably not planning to send James to France. At this point the French were experiencing the first signs of the civil war which would plague them for thirty years.38 Instead Fleming and Orkney, ‘with a strong band of the leading men of Lothian’, embarked on what appears to have been a military or political campaign in East Lothian with James present as a royal figurehead.39 It was this action, in conjunction with the events of the previous year, which formed the ‘provocation’ offered to James Douglas, to which Bower refers.40 Douglas, with his own following of Black Douglas supporters, came out of Edinburgh and pursued the royalist force. When the two sides met on Long Hermiston Moor on 14 February, the Douglases destroyed the prince’s supporters ‘after a terrible fight’, killing Fleming and capturing ‘various nobles and knights’.41

It was in these circumstances, with a battle imminent between James Douglas and Fleming, that Prince James was left in North Berwick to be ‘rowyt to the Bass’ in the company of ‘Orkney and a decent household’.42 Bower’s statement that James waited ‘for the chance of a ship on the Bass’ and the fact that he was delayed over a month before one arrived shows that there can have been no pre-arranged plan to send James to France at this point.43 Instead James was sent to the Bass Rock to avoid being caught up in a fight with the Douglases which could have led to his capture or death.

In the middle of March James and Orkney finally obtained a passage on a ship of Danzig, the