Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: BoD - Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

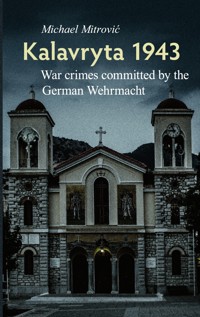

During the Second World War, soldiers of the German Wehrmacht destroyed over a hundred places in Greece. In the process, they shot tens of thousands of Greeks, often as a so-called punitive measure. One of the most horrific crimes was committed in Kalavrita on the Peloponnese in December 1943. The events are vividly described from various perspectives. The crimes committed by the German Wehrmacht in Kalavryta are just one of many crimes committed during this war. The number of victims of the fascist regime of the NSDAP and its allies is endless, and the atrocities committed are almost unparalleled in their cruelty. And yet many still want to disavow these factually proven acts. Autocratic governments, right-wing populist and extreme right-wing movements and parties are experiencing a worldwide renaissance. In Germany, too, history is being falsified at will. Disinformation and lies, anti-Semitism and xenophobia are part of everyday life, and fascism is on the rise again. Especially in times like these, which are largely reminiscent of the Weimar Republic, maintaining a culture of remembrance is one of the most important issues alongside all the global challenges, because the past has impressively demonstrated where history can lead. Using the example of the war crimes committed in Kalavryta in 1943, this book presents a semi-documentary, but also subjectively narrated, fact-based account of the events.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 130

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

„Nach Auschwitz ein Gedicht zu schreiben, ist barbarisch.“ "To write a poem after Auschwitz is barbarous." Theodor Adorno „Kulturkritik und Gesellschaft“ 1949/1951

„Noch aus der Distanz eines halben Jahrhunderts sah er sich nicht imstande, es in Sätze zu fassen, die wirklich etwas bedeuten.“ "Even from a distance of half a century, he did not feel able to put it into words that really meant anything." Daniel Kehlmann „Lichtspiel“ 2023

„…Hitler und die Nazis sind nur ein Vogelschiss in unserer über 1000jährigen Geschichte.“ "Hitler and the Nazis are just a speck of dust in our more than 1,000-year history." Alexander Gauland 2.6. 2018

Table of contents

Foreword

1 A short hike in Kalavryta (Ouverture)

2 In Greek captivity (german point of view)

3 From Kalavryta to Feneos (Interlude)

4 Shooting of the prisoners (greek point of view)

5 Kalavryta in midsummer (Interlude)

6 A survivor in Kalavryta

7 Gypsy love (digression)

8 Return of the Andarts to Kalavryta (from the communists‘ point of view)

9 By rack railway from Diakofto to Kalavryta (digression)

10 The Battle of Lalas

11 The trip from Patras via Kalavryta to Kokkoni (swan song)

12 Bloody Birthday

Epilogue

Timeline

Foreword

In October 1944, the last units of the German Wehrmacht left Greece, which had been occupied since spring 1941. The Greek people had never resigned themselves to the occupation of both the Italian and German armies, even though their own troops had surrendered. Resistance groups formed throughout the country until the formation of the “regular” underground army ELAS. Their activities inflicted heavy losses on the Germans, which in turn prompted them to take enormous, unjustifiable measures of atonement. Hundreds of villages were burnt down, hostages shot and livestock confiscated. These were undoubtedly capital war crimes and fundamental human rights violations that the German public and the respective post-war governments have not even come close to addressing to this day.

Both sides, the Greek and the German, are unwilling to make a big deal of the issue. Greek foreign policy repeatedly and discreetly but clearly reminds us of reparation demands and the repayment and interest payment for a forced loan extorted during the war. But then the Germans are the most loyal vacationers in the country, so such old bills are disturbing, especially as hardly any of the contemporary witnesses are still alive.

When I set foot on Greek soil for the first time, in 1973, it was very difficult to find out anything objective about the history of Greece in the 20th century. To be honest, I had no intention of doing so. For one thing, the last phase of the military junta was just beginning. I was hanging out at the university in Athens or in forbidden pubs where Theodorakis‘ music was played. But then again, due to my Serbian ancestry, I came across the Nazi atrocities in Yugoslavia. My relatives had often told me that, as the saying went, one hundred locals were shot for one German soldier killed by the partisans. The terrible massacres in Kragujevac and Kraljevo, where 5,000 hostages were shot and entire school classes and their teachers were led to the slaughter, were in front of our eyes.

It was only many years later, after studying the languages and history of the Balkans, that I set out in search of the truth. Precisely because I was no ordinary tourist in Greece (and in Serbia), but shared everyday life there with my German-Greek friends, I wanted to delve deeper into the web of past, present and future.

Perhaps I had unconsciously kept myself away from the knowledge of the terrible atrocities committed by the Germans in my adopted country of Greece over the years. Perhaps I wanted to preserve a spiritual refuge so that I could at least rest my soul in the successor country of classical antiquity. My motherland had stained its hands with blood forever through the Shoah. During the Second World War, my fatherland had had to pay a tremendous toll in blood, mainly due to the strong activities of Tito‘s resistance fighters - also in a parallel civil war, the Royalists against the Communists. 30 years of regular residence in my domicile in the Bay of Corinth, at the age of almost 50, brought the events of the disastrous war years home to me. On my bicycle tours with my mountain bike, I crossed the entire northern Peloponnese. I was repeatedly reminded of the beauty of the hike from Diakofto to Kalavryta, right next to the famous rack railroad. None of my Greek friends had ever pointed out to me to visit the memorial, the museum or the stopped clock on the church tower. That‘s fine, of course. Nobody wants to poke their friends‘ noses into the most embarrassing places in their home country. The same certainly applies to Weimar: Glory for the German classical poetry guard, followed by the commemoration of Buchenwald. “Disaster tourism” would do more harm to the cause than contribute to general enlightenment and education.

My Greek interlocutors were also always extremely taciturn and reserved when talking about the war and the civil war. Neither the one nor the other boasted about their respective “heroic deeds”. That‘s probably always the case: people who have been involved in war for years, whether they are regular soldiers or insurgents, almost never talk about it after the end of hostilities. And if they do, it‘s usually general phrases, hardly ever personal experiences. That‘s how I experienced it with my father, who the Germans took to Germany as a prisoner of war for forced labor after the Yugoslavian army surrendered in 1941.

Tourists generally don‘t want to know about all these atrocities. On the one hand, that‘s not a bad thing. Some even see themselves as messengers of peace who, on top of that, want to help “poor Greece” with their good money and only show good intentions by often making friends with the locals. On the other hand, a person with a reasonable interest in politics and history cannot possibly have never noticed anything that strains the balance between two states or cultures. The only question then is to what extent they want to and can inform themselves about it. Knowledge of the national language may play a role here. However, unlike in the 1970s, it has long been possible to find out about all aspects of contemporary Greek history in English or German.

In any case, at some point I had passed the point of no return. Just as I used to admire the traces of antiquity everywhere, inspecting them and relating them to the present, I now encountered the traces of the terrible crimes committed by the German Wehrmacht during the Second World War at every turn. Suddenly, place names and regions that I had often crossed on my bike took on a completely new connotation, a taste of smoke and destruction, of suffering and death, and conversations with locals, descendants or newcomers were usually difficult to get going. Only when I revealed my Serbian ancestry did my counterpart thaw out at all. Even acquaintances only told me years later that an uncle had to witness everything as a child in December ‘43. Talking about the horror means suffering yourself, taking part. It hurts again and again!

But perhaps it hurts the Greeks so much precisely because the Germans, who came in such large numbers as tourists to the beautiful Greek beaches in the post-war period, even if not to Kalavryta, never said a word about what their ancestors had done to the people there. Worse still, no German post-war government has ever made an effort to really come to terms with the events and strive for genuine reconciliation. Almost 57 (fifty-seven) years after the massacre, in 2000, a top German politician, Federal President Rau, visited the site for the first time. Apart from gracious apologies and mild gifts, nothing came of it. Surely the German government cannot adequately compensate for all the crimes committed during the war. There were simply too many! The Greek people, on the other hand, feel a great injustice and helplessness towards “big” Germany. The way German tourists have been welcomed and entertained for decades shows that all is forgiven! But it must never be forgotten!

With this in mind, I have attempted to portray the massacre in Kalavryta in December 1943 on the basis of narrative and documentary reports. The capture and shooting of the German company, which ultimately led to the catastrophe as an “atonement measure”, is described from both the German and Greek perspective. Then I let a survivor have her say. This is followed by the return of the insurgents, who, of course, did not risk a battle with the Germans. The Wehrmacht‘s large-scale purge of the partisans in the northern Peloponnese is depicted in the battle of Lalas. It concludes with the birth of a girl in the midst of the chaos on the day the town was destroyed. She is, so to speak, the symbol of renewal, the phoenix rising from the ashes. It is a tiny hope that even in the darkest times a small light shines, a new person enters the world. But with what a terrible mortgage... These serious texts are interspersed with small sketches and experiences that arose during my early stays in Kalavryta. They show the initial “naive” enthusiasm for the landscape and culture. Soon, however, misgivings interfere, until finally a detailed description of the prehistory and the massacre itself make up the main part of my notes.

It goes without saying that with the chosen method, many details are mentioned or described several times, whether from different perspectives or in order to present facts in their organic development. In this way, the reader‘s awareness of the entire, horrific course of the catastrophe grows over the course of reading the book, which refrains from presenting an introductory analytical text at the beginning in order to outline the topic and classify the historical facts. Those who absolutely need this should start with the sixth and final insert “swan song” - “The Voyage from Patras to Kokkoni” and follow the chronological sequence of events.

Crimes against humanity never become time-barred! No matter where they were committed! No matter who committed them, they will never be forgotten, even if some German politicians believe that the Nazi era - and therefore the war crimes for which the Nazis are responsible - are just “a speck of dust in our 1000-year history”. A thousand generations later, we will still be able to read about what German soldiers did to innocent Greek people back in December 1943. And for all eternity: guilt can only be forgiven if both sides actively work on it!

1 A short hike in Kalavryta (Ouverture)

Several friends had already told me that you can hike along the rack railway from Diakofto to Kalavryta.

They raved about the beauty of the route, which is part of the E4 European Hiking Trail. Of course, I couldn‘t experience this on my mountain bike. The upper part of the road from Kalavryta to around Ano Zahlorou runs right next to the railroad line. But riding on asphalt at around 15km/h (25-30km/h downhill) is quite different from meditative hiking. Incidentally, you can hardly hear the sounds of nature when cycling, but rather the wind and other road users. To whet my appetite, I decided to leave my bike in Kalavryta and hike downhill for an hour or two. To be honest, I found it hard to imagine how to make progress along/on the railroad track. So it was an experiment! The day wasn‘t too hot and I set off in the early afternoon, directly from the small station. A full train had just started its return journey to the sea, so there was nothing to catch up with. And I would hear and see the oncoming train. There was no sign of any official recognition or marking of the “E4”. There was a well-trodden path next to the track, which I could easily follow.

At that time, I had not yet studied the details of the Nazi massacre in December 1943, I only knew the broad outlines. Otherwise I would hardly have walked along these paths with a clear conscience. The first stop after about an hour, for example, was the village of Kerpini, which had been razed to the ground by the Germans. But I only had eyes for the natural beauty: the Aroania Mountains rising up on the right with Chelmos to the south-east, the gentler hills to the left, the Vouraikos flowing lively to my left. When the railroad line crossed the river over a large arched bridge, I stopped. I had a little respect for the fact that a train might be coming while I was in the middle of the bridge. In reality, however, I had to turn back anyway due to time constraints. I had been walking for 90 minutes without a break. If I took a break now, I would be back in Kalavryta in the late afternoon. The continuation or rather the complete tour (in both directions) only followed six years later...

2 In Greek captivity (german point of view)

The whole gossip started at the beginning of September with the capitulation of the Italians. It was actually a good thing, because the locals hated the Italians, because of 1940 of course, and there had been a lot of problems. They appreciated us, on the other hand, because of our technology and our culture. At least the simple, normal Greeks did. We also hold ancient Greek culture in high esteem, we learned all about it at school. But now the communist Andarts were getting bolder and bolder. They picked on their own people, incited them against us. They were against all occupying armies, whether German or Italian. You can kind of understand that. But they got their orders from Moscow and that‘s where the fun ended! Their activities increased rapidly and, above all, they disrupted our important supply routes. In any case, the day after the Italians surrendered, we marched into the mountain village of Kalavryta and disarmed the Italian unit stationed there. Then we went back to the coast, where we spent a few quieter days. In principle, we no longer controlled the inner area of the Peloponnese and we could observe an increase in Andart activity from week to week. We had long suspected that Kalavryta in particular was a center of this activity, especially the monastery of Agia Lavra. However, the Italians had not been effective either.

In mid-October, a large-scale operation was promptly ordered to reconnoitre the area between the north coast and Kalavryta and, if possible, to confront and defeat the enemy. Our unit was assigned to reconnaissance along the rack railway from Diakofto to Kalavryta.